Summary

While schizophrenia pathogenesis involves both genetic and environmental factors, their specific combinations remain ill-defined. Here we show that deficiency in promoter VI-driven BDNF expression, combined with early-life adversity, results in schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes. Promoter VI mutant mice (Bdnf-e6−/−), when exposed to postnatal stress including hypoxia or social isolation, exhibited deficits in social interactions, spatial memory, and sensorimotor gating reflected by prepulse inhibition (PPI). Neither early-life stress nor Bdnf-e6 deficiency alone caused these abnormalities. Moreover, postnatal stress increased blood corticosterone levels of wild-type mice, and administration of corticosterone to Bdnf-e6−/− mice without early-life stress also resulted in PPI deficits and social dysfunction. Finally, the PPI deficits in postnatally stressed Bdnf-e6−/− mice were rescued by treatment with the corticosterone antagonist RU-486, or the BDNF mimetic TrkB agonistic antibody. Thus, we have identified a pair of genetic and environmental factors contributing to schizophrenia pathogenesis and providing a potential strategy for therapeutic interventions for schizophrenia.

Subject areas: neuroscience, behavioral neuroscience, molecular neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Bdnf-e6−/− combining early-life stress results in schizophrenia-like phenotypes

-

•

Neither early-life stress nor Bdnf-e6 deficiency alone causes these abnormalities

-

•

Corticosterone treatment to Bdnf-e6−/− mice also induces PPI deficits

-

•

PPI deficits can be rescued by treatment with RU-486 or TrkB agonistic antibody

Neuroscience; Behavioral neuroscience; Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a severe psychiatric disorder that affects 21 million people worldwide, resulting in a huge social and economic burden. SCZ patients exhibit difficulty in thinking, perception, emotion, and language. Typically, the onset of SCZ is in late adolescence (16–25 years) or early adulthood, important years for a young adult’s social and vocational life (Addington, 2007). The life expectancy for SCZ is about 10–25 years shorter than that of healthy individuals. There are three clinical symptoms: positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions and psychosis), negative symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal, affective disturbances, impoverished speech), and cognitive deficits (e.g., poor executive function, working memory, and attention problems) (Hustig and Norrie, 1998). Two well-known groups of antipsychotics, including the first-generation (e.g., haloperidol and chlorpromazine) and the second-generation antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone and olanzapine), could to, a certain extent, alleviate the positive or negative symptoms (Remington, 2003). However, these medicines have little effects on cognitive impairments, and often elicit significant side effects (Mintz and Kopelowicz, 2007). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new medicines that attenuates all three symptoms and have less side effects. These will require a better understanding of SCZ mechanisms and better animal models.

As a multi-factorial psychotic disorder, SCZ exhibits considerable heterogeneity and complexity in its causes. A number of behavioral phenotypes are reported across all subtypes of SCZ, including changes in locomotor activity and social behavior, cognition, and executive functions, as well as deficits in sensorimotor gating (Howell and Pillai, 2014; McGrath et al., 2014; Wilson and Koenig, 2014). Human twin studies have shown that the concordance rate in monozygotic twins with SCZ is 40–60%, significantly higher than those in the dizygotic twin and non-twin siblings, suggesting a strong genetic component in SCZ risk (Kahn et al., 2015). There are more than a hundred loci (one locus may contain several schizophrenia susceptibility genes) each making a small contribution to schizophrenia risk (Foley et al., 2017). A recent, two-stage genome-wide association study reported that 287 distinct genomic loci containing common variants associated with schizophrenia (Trubetskoy et al., 2022). Using fine-mapping and functional genomic data, 120 genes, including 106 protein-coding ones, have been identified. It is likely that those genes may play a role in the fundamental processes related to neuronal differentiation, synaptic organization, and function (Trubetskoy et al., 2022). The causal variants, however, that drive these associations and the biological consequences of these variants, are still largely unknown.

In addition to genetic risk factors, environmental perturbations, especially those during early development, play a key role in the etiology of schizophrenia (Meyer and Feldon, 2010). Hypoxia occurring during pre- and perinatal periods could cause neuronal alterations in the developing brain, resulting in an increase in the susceptibility for SCZ in the offspring (Cannon et al., 2002). The epidemiological studies of the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945 and the Chinese famine of 1959–1961 suggest that prenatal malnutrition may lead to a two-fold increase in the risk of developing SCZ in adult life (St Clair et al., 2005; Susser and Lin, 1992). Additional developmental insults include lowered prenatal vitamin D intake, viral infections, smoking, cannabis use, social defeat and childhood trauma (Davis et al., 2016). However, numerous studies have shown that risk genes or environmental factors alone are not sufficient to cause the disorder. It is widely believed that pathogenesis of SCZ involves both genetic and environmental factors. The “two-hits” hypothesis suggests that interactions between SCZ-risk genes and environment hazards are critical for the etiology as well as the heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders including SCZ (Davis et al., 2016). A major challenge in the field is to determine the pair (which gene(s) interact with what kind of environmental disturbance).

Compared with human studies, animal models are better suited to unravel how genes and the environment interact to lead to an ultimate manifestation of schizophrenia (G×E interactions) because G and E could be altered and manipulated independently (Jones et al., 2011). An ideal animal model of SCZ should satisfy three criteria: face validity (displays core schizophrenia symptoms), construct validity (is based on human disease mechanisms), and predictive validity (exhibits antipsychotic effectiveness and utility in discovering new therapeutics) (Jones et al., 2011). Unfortunately, mutant mouse models based on schizophrenia susceptibility genes only mimic certain “face” features of SCZ: no one gene can induce all symptoms of SCZ or account for SCZ etiology (Tordjman et al., 2007). Considerable evidence suggests that several key neurotransmitters, including dopamine, glutamate, serotonin, and GABA, are involved in SCZ pathophysiology (Schmidt and Mirnics, 2015; Stahl, 2018). However, drug-induced models can only imitate some aspects of SCZ phenotypes (McKinney and Moran, 1981). Furthermore, given the heterogeneity in schizophrenia, animal models based on manipulation of neurodevelopment or brain lesion could not consistently replicate the full syndrome of this complex disorder. Thus, research in schizophrenia has been significantly hampered by the lack of good animal models.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has long been thought to be involved in the development of schizophrenia (Di Carlo et al., 2019). BDNF plays important roles in neuronal differentiation and synaptogenesis during development, synaptic transmission, and plasticity in the adult, as well as behaviors relevant to SCZ (Chao, 2003; Figurov et al., 1996; Ji et al., 2010; Lohof et al., 1993; Martinowich et al., 2007; Molteni et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2000). There is an association between SCZ and genetic variants of Bdnf including Val66Met and C270T polymorphisms (Neves-Pereira et al., 2005; Szekeres et al., 2003). Aberrant expression of BDNF, its receptor TrkB, and downstream Akt and ERK signaling has been observed in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and blood plasma of SCZ patients (Emamian et al., 2004; Green et al., 2011; Issa et al., 2010; Szamosi et al., 2012; Weickert et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2013; Yoshimura et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2010). There is also evidence that the effects of antipsychotic drugs such as clozapine are mediated at least in part by the BDNF-TrkB signaling (Pedrini et al., 2011).

The genomic structure of the Bdnf gene is quite complex. There are nine promoters located in the upstream of 5′ untranslated regions (5′ UTR) of nine small exons, and each is spliced onto a common exon, exon 10, which encodes the pre-proBDNF protein (Pruunsild et al., 2007). Substantial evidence suggests that different promoters drive the expression of different Bdnf transcripts in different brain regions, cell types (neurons versus glial cells), sub-cellular compartments (e.g. soma versus dendrite), and different developmental stages (Baj et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2009). Further, the nine Bdnf promoters are regulated by different transcriptional and epigenetic factors, and contribute to diverse physiological functions (Pruunsild et al., 2007). For example, selective disruption of Bdnf promoters I or II leads to thermogenesis deficits and obesity (McAllan et al., 2018; You et al., 2020). Moreover, Bdnf promoter IV, which drives activity-dependent BDNF transcription (Hong et al., 2008; Sakata et al., 2009), plays a key role in behavioral perseverance through the regulation of GABAergic transmission (Jiao et al., 2011; Sakata et al., 2009, 2013). However, it remains unknown which Bdnf promoter(s) is critically involved in SCZ.

The present study is designed to construct a GxE model for SCZ with two critical features: 1) an interaction between the SCZ relevant gene Bdnf and developmental stress; 2) a profile of behavioral abnormalities highly relevant to SCZ. A number of studies have shown the association of genetic variants in human Bdnf exon 6 with schizophrenia (Nanko et al., 2003; Szekeres et al., 2003; Zintzaras, 2007). Thus, we used the mouse line with the specific disruption of Bdnf promoter VI (Bdnf-e6−/− mouse) as the “first hit.” We also tested several developmental stresses as the potential “second hit.” We asked whether such a G×E mouse model could display core SCZ behaviors/symptoms (face validity) and help address the etiology of SCZ (construct validity). We further examined whether treatment with a TrkB agonist or a drug that attenuates developmental stress could rescue the behavioral phenotypes of the SCZ model. Our results reveal a pair of GxE factors important for schizophrenia pathogenesis, and laid a foundation for new therapeutic interventions for human SCZ.

Results

Bdnf-e6 disruption alone did not elicit schizophrenia-like behavior

Genetic and imaging studies in humans have pointed to a potential role of Bdnf promoter VI in schizophrenia. To better study whether and how dysregulation of Bdnf promoter VI might contribute to schizophrenia, we employed the mouse knock-in line in which Bdnf transcription through its promoter VI is selectively disrupted (Maynard et al., 2016). In this line (Bdnf-e6−/−), an eGFP cassette was inserted directly downstream of the Bdnf exon 6, followed by multiple STOP codons. As such, Bdnf promoter VI drives the production of a transcript containing the 5′UTR-eGFP-Bdnf coding exon IXa, which, in turn, is translated into eGFP instead of BDNF protein (Figure S1A).

Genotyping analysis revealed a 566-base pair wild-type (WT) fragment and a 367-base pair mutant fragment in WT and Bdnf-e6 mutant mice, respectively (Figure S1A). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments confirmed that Bdnf-e6 mRNA is highly enriched in the brain instead of peripheral tissues in adult WT mice (Figure S1B) (Aid et al., 2007). In WT brains, Bdnf-e6 mRNA was more abundant in the hippocampus and mPFC than other regions (Figure S1B). In Bdnf-e6−/− brains, whereas Bdnf-e6 transcript was completely absent, the levels of Bdnf-e1, Bdnf-e2, and Bdnf-e4 transcripts were relatively normal in the hippocampus and mPFC (except for a modest decrease in Bdnf-e4 transcripts in the hippocampus) (Figure S1C and S1D). Western blotting detected GFP protein in various regions in the Bdnf-e6−/− but not WT brains (Figure S1I). Immunohistochemistry showed that Bdnf-e6-eGFP was highly enriched in the hippocampus in the mutant mice (Figure S1J). Additionally, Bdnf-e6 deficiency did not result in weight change, motor impairments (Figures S1E and S1F), and enlargement of lateral ventricles (Figure S1K).

We conducted a battery of schizophrenia-relevant behavioral tests in the adult male Bdnf-e6−/− mice. In the open field test, the overall distance traveled was considered as an indicator of the locomotor output, which is often elevated in schizophrenia animal models (Seibenhener and Wooten, 2015; Tatem et al., 2014). As shown in Figures S1G and S1H, Bdnf-e6−/− mice exhibited normal locomotion activity, but spent less time in the center zone, suggesting a mild elevation of anxiety (p = 0.0253). The three-chamber test assesses social affiliation and social memory, two endophenotypes often impaired in schizophrenia. In the sociability test, both Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice displayed normal social interaction, spending more sniffing time with a cup containing a live mouse (Stranger 1) rather than with an empty cup (Figure 1A, p = 0.0002 and 0.0008 for WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice, respectively). Similarly, these mice also preferred a novel mouse (Stranger 2) instead of a familiar individual (Stranger 1) in the social novelty preference test (Figure 1B, p = 0.0229 and 0.0326 for WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice, respectively), indicative of intact social memory. In the Morris water maze (MWM) test (Figure 1C), WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice spend a similar amount of time learning the position of the hidden platform (except a small difference on day 6) (Figure 1D). There were also no differences in the latency to platform between WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice during the probe trial (Figure 1E, p = 0.3748). However, the Bdnf-e6−/− mice did exhibit a small decrease in the time spent (Figure 1F, p = 0.0029) and the number of crossing in the target quadrant (Figure 1G, p = 0.0271), compared with WT mice, suggesting an impaired spatial memory. Finally, we performed a prepulse inhibition (PPI) test to examine sensorimotor gating, another common schizophrenia-related endo-phenotype. Bdnf-e6−/− mice showed a normal startle response (Figure 1H, p = 0.3303) as well as PPI at all prepulse intensity levels (Figure 1I), suggesting that Bdnf-e6−/− mice have a normal sensorimotor gating function.

Figure 1.

Behavioral characterization of Bdnf-e6 mutant mice

(A and B) Three-chamber test. Both Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice spent more time in the chamber containing the “Stranger 1” in the sociability test (A) and increased preference for the “Stranger 2” in the social novel preference test (B).

(C) Morris water maze (MWT) test. Schematic diagram of the Morris water navigation task.

(D) In the learning trials, WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice showed the same escape latency, except on day 6.

(E–G) In the probe trial, Bdnf-e6−/− mice exhibited no the latency to reach the platform (E), but spent less time in the target quadrant (F), and crossed the platform location with fewer times, compared with WT mice (G).

(H–J) PPI test. Bdnf-e6−/− mice showed no changes in the startle response to 120-dB sound (H) and the average PPI ratios for all intensities (I). Schematic diagram for PPI test (J). In this and all other figures, data are shown as mean ± SEM. ns, no significant change. ∗ indicates significant difference between groups. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. The number of animals used for each test was shown in the bar graph or stated in figure legend. (A–I: unpaired Student’s t test).

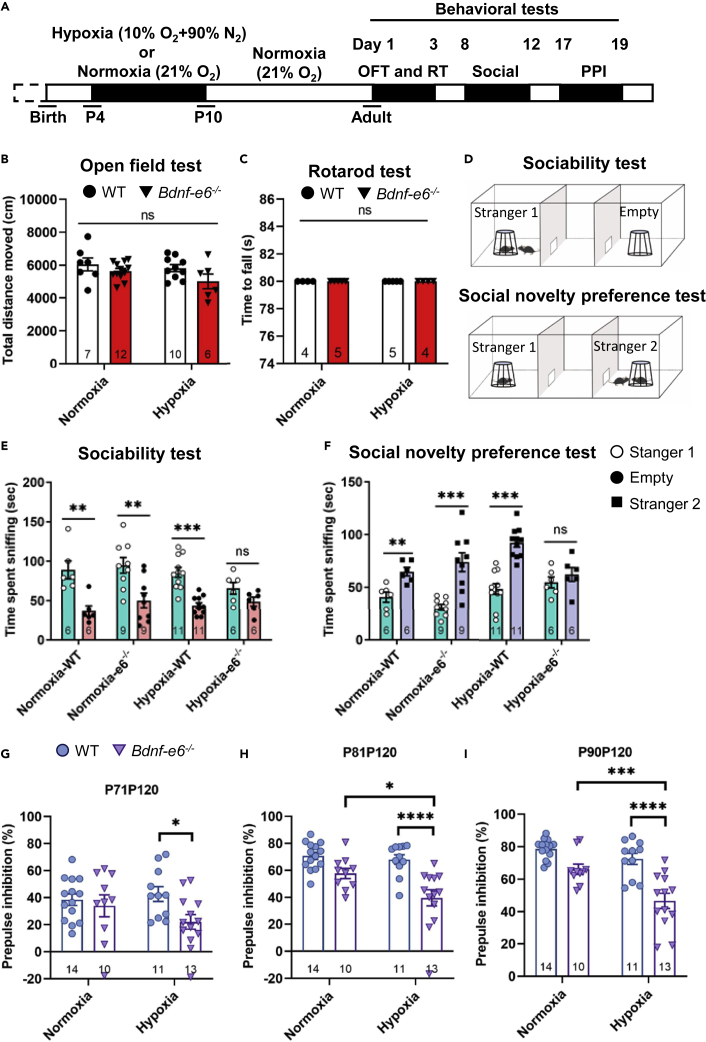

Bdnf-e6 disruption plus postnatal hypoxia-induced schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes

Early-life adversity is a known risk factor that increases the likelihood of schizophrenia (Gretchen-Doorly et al., 2011; van Os et al., 2010). We therefore tested whether postnatal stress such as hypoxia could induce schizophrenia-like phenotypes in adult Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Pups of Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice were raised under either normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (10% O2) for 6 consecutive days, starting from postnatal day 4, and behavioral tests were performed in adulthood (2∼3-month-old) (Figure S2A). Thus, there were four experimental groups: normoxia-WT, hypoxia-WT, normoxia-e6−/−, and hypoxia-e6−/−. Early-life hypoxia resulted in a transient reduction in body weights during postnatal development in both WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figures S2B–S2D). Mice exposed to hypoxia were smaller than age-matched controls (WT) reared in normoxia in three (PND 20, Figure S2B) and five weeks (PND 36, Figure S2C), but not in nine-week animals (PND 63, Figure S2D). It is noted that Bdnf-e6−/− mice suffered slightly more (three-week) or the same (five-week) weight loss as the WT mice during development, and the weight loss recovered completely in the adulthood (nine-week) (Figure S2D).

We next tested whether the transient developmental adversity would lead to differential impacts on WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice. In an open field test, there was no difference in “total running distance” among the four groups, suggesting that early-life stress does not elicit locomotion deficits (Figure 2B). Likewise, motor coordination and motor learning skills appeared normal as measured by the rotarod test in Bdnf-e6−/− mice regardless of whether they experienced early-life hypoxia or not (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Postnatal hypoxia induced social dysfunction in hypoxia-e6−/− mice

(A) Schematic diagram depicting the experimental design. WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice at postnatal day 4 (P4) were subjected to hypoxia or normoxia living environment for seven consecutive days, and raised to adult in normoxia. Open field, Rotarod, social interaction, and PPI tests were performed, successively.

(B) The total running distance of normoxia- and hypoxia-treated mice in the open field test.

(C) The time to fall of normoxia- and hypoxia-treated mice in the Rotarod test.

(D) Experimental design of social interaction test.

(E and F) Sociability (E) and social novelty preference (F) of normoxia- and hypoxia-treat mice. Note that Bdnf-e6−/− mice lost social and sociability and novelty preference after postnatal hypoxia.

(G–I) Effect of hypoxia on PPI. The average PPI ratios at all intensities were selectively decreased in the postnatal hypoxia-e6−/− mice (B–C, G–I: two-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (E–F) unpaired Student’s t test).

To explore whether such gene (Bdnf-e6−/−) and environment (postnatal hypoxia) (GxE) interaction also affect other schizophrenia-related behaviors, we conducted a three-chamber test. In the sociability test, Bdnf-e6−/− mice with postnatal hypoxia spent the same amount of time exploring the empty cup and the one with a live mouse (Stranger 1, Figure 2E). In contrast, all other three groups preferred to spend time with a live mouse (Figure 2E). Thus, disruption of Bdnf-e6 transcription together with early life hypoxia may generally be uninterested in social activity. In the social novelty preference test, WT mice spent more time with a new mouse (Stranger 2, Figure 2F) than with the familiar mouse (Stranger 1), regardless they experienced hypoxia or not. The Bdnf-e6−/− mice without postnatal hypoxia also exhibited a preference for a novel social stranger (Figure 2F). In marked contrast, the hypoxia-e6−/− mice showed no apparent preference (p = 0.3894) (Figure 2F). Thus, Bdnf-e6 mice with early life stress may also affect the ability of animals to socialize with new peers. The sociability and social novelty preference tests together revealed a strong interaction between Bdnf-e6−/− and postnatal hypoxia, suggesting the role of a specific GxE pair in social affiliation and social memory.

Nest building is another stereotyped social behavior thought to be associated with mating and offspring bounding (Jirkof, 2014). The average nesting score was significantly decreased in the hypoxia-e6 mice measured after 24 h, compared with either normoxia-WT or normoxia-e6 mice (Figure S3B), indicative of the impairment of nesting behavior in hypoxia-e6 mice. However, in mice with postnatal hypoxia, Bdnf-e6−/− mice appear to exhibit more severe, although not statistically significant, nest-building impairment compared with WT mice (Figures S3A and 3C). There was almost no score 4 nesting in hypoxia-e6−/− mice (Figure S3C). Thus, Bdnf-e6 deficiency might elicit further nest-building impairment under early life hypoxia.

Figure 3.

Juvenile social isolation induced hyperactivity and social dysfunction

(A) Schematic diagram depicting the experimental design. Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice at postnatal day 21 were subject to isolation rearing (PIR) or social rearing (PSR) for four consecutive weeks (P21–P49). Different types of behavioral tests were conducted in a schedule as highlighted.

(B) The total running distance of PIR and PSR mice in the open field test.

(C) The duration time of PIR and PSR mice in the center of open field.

(D and E) Social behaviors of PIR and PSR mice were measured by time spent sniffing in the sociability test and social novelty preference test. Note that Bdnf-e6−/− mice with PIR showed deficits in social novelty preference but not in sociability test. (B–C: two-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. D–E: unpaired Student’s t test).

As the MWM test already showed spatial memory deficits in Bdnf-e6−/− mice without hypoxia (Figures 1D–1G), we sorted to find a cognitive test more sensitive to reveal the GxE impact. One-trial novel object recognition is purely based on the ability of rodents to differentiate the novel object from a familiar one. During the acquisition phase, there was no significant difference among all four groups in the exploration times of two identical objects at a 5-min delay (data not shown). In the retention phase, the subject mouse was presented with a novel object alongside the familiar one. Hypoxia had a negative impact on the ability to discriminate between novel versus familiar objects (Figure S3D). Bdnf-e6 deficiency additionally diminished, on top of hypoxia, the ability to distinguish “old” from “new” object (Figure S3E). These results suggest that Bdnf-e6 could also exhibit cognitive deficits if they experience early life stress.

We next examined PPI, a behavioral test more directly linked to schizophrenia (Carr et al., 2016; Papaleo et al., 2016). The level of PPIs at all prepulse intensities (71, 81, and 90 dB) were dramatically decreased only in the hypoxia-e6 group (Figures 2G–2I). Thus, disruption of Bdnf-e6 expression, together with postnatal hypoxia, elicits the PPI deficits that are relevant to schizophrenia.

Juvenile social isolation also induced schizophrenia-like abnormalities

The pronounced impact of postnatal hypoxia on schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes prompted us to examine whether other forms of early-life adversary, such as social isolation, also elicit schizophrenia-like behaviors. Postweaning (21-day-old) animals were randomly assigned to social-rearing (PSR, a number of animals were group-housed) or isolated-rearing (PIR, animals were housed individually in a single cage) groups for four weeks, and behavioral tests were performed on adults (Figure 3A). In the open field test, PIR elicited a general increase in locomotion activity (total running distance) in both genotypes compared with PSR (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the disruption of Bdnf-e6 selectively decreased the duration time in the center zone for PSR but not PIR (Figure 3C). It is possible that PIR may have masked the effect of Bdnf-e6 disruption, which could be revealed in social-rearing conditions.

In the sociability test, isolated-rearing had no effect on either Bdnf-e6−/− or WT mice. Animals of both genotypes spent more time interacting with a mouse (Stranger 1) over an empty cup, regardless in PSI or PIR (Figure 3D). In the social novelty test, animals subjected to PSR interacted more with a novel (Stranger 2) over a familiar (Stranger 1) partner regardless of genotypes (Figure 3D). In contrast, PIR essentially eliminated the preference to interact with novel partners, and both WT and Bdnf-e6 mice spent the same amount of time with Stranger 1 and Stranger 2 (Figure 3E right), suggesting that isolation alone may be sufficient to induce deficits in interaction with a novel partner.

In the PPI test, PIR generally suppressed PPIs in all prepulse intensities (71, 81, 90dB) (Figures 4B–4D). Disruption of Bdnf-e6 expression seemed to further reduce the PPI ratios at prepulse intensities of 71 and 81 dBs, although such an effect did not reach statistical significance. Thus, postweaning social isolation seems to elicit a strong inhibition in sensorimotor gating behaviors, making it difficult to reveal the additional impact of Bdnf-e6 disruption. This idea was further supported by the fact that adult isolation rearing (AIR), which is believed to be relatively weaker than PIR, can induce PPI deficiency in all prepluse intensities (71, 81, 90 dBs) in Bdnf-e6−/− mice, but not WT mice (Figures 4F–4H). Taken together, these results suggest that impairments in Bdnf-e6 expression may serve as a genetic factor that works together with environmental stress during postnatal development or adults to induce schizophrenia-like endophenotypes.

Figure 4.

Juvenile isolation induced PPI deficits in both Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice, but adult isolation induced PPI deficits only in Bdnf-e6−/− mice

(A and E) Experimental design. Juvenile social isolation paradigm is same as Figure 3A. For adult social isolation, Bdnf-e6−/− and WT adult mice at postnatal day 70 were subject to isolation rearing (AIR) or social rearing (ASR) for four consecutive weeks (P70–P98), PPI test were conducted at P100–P103 (E).

(B–D) PPI ratios at 71, 81, and 90 dB were all decreased in PIR mice ( B–D: two-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test).

(F–H) Prepulse inhibition of all intensity (71, 81, and 90 dB) are demonstrated, respectively. Note AIR treatment induce no deficient PPI of all prepulse intensity in WT mice, but dramatically decreased PPI in Bdnf-e6−/− mice.

Similar to Bdnf-e6, Bdnf-e4 is a major regulator of GABAergic function and is expressed in brain regions relevant to schizophrenia, such as hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus (Maynard et al., 2016). Thus, we examined whether Bdnf-e4−/− mice also exhibit schizophrenia-like behavioral phenotype under early-life environmental stress. Our data showed that Bdnf-e4−/− mice, when subjected to postnatal hypoxia or juvenile social isolation, do not exhibit deficits in PPI (Figure S4). These results suggest that Bdnf-e6 deficiency animals when exposed to environmental stress are more likely to develop schizophrenia-like phenotype.

An increase in blood corticosterone together with Bdnf-e6 disruption led to schizophrenia-like endophenotypes

Plasma corticosterone is released in response to environmental stress and is used as an indicator for bodily stress responses in rodents and humans. Therefore, we investigated whether postnatal hypoxia or social-isolation paradigm can increase the levels of corticosterone. Consistent with previous findings (Barlow et al., 1975; Krishnan et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2019), plasma corticosterone (CORT) levels were increased with exposure to environmental stresses (Figures 5A–5C), including postnatal hypoxia, adolescent and adult social isolations in WT mice.

Figure 5.

Environmental stress increased plasma corticosterone level in WT mice

In all figures, schematic diagrams depicting the experimental design are shown on top, whereas plasma corticosterone levels are shown below.

(A) WT mice at postnatal day 4 were exposure to hypoxia or normoxia social living environment for seven consecutive days (P4–P10). After environmental stress, mice were reared to adult in normoxia social living environment. Note that postnatal hypoxia significantly increased the plasma corticosterone level in adult (P60).

(B) WT mice at postnatal day 21 were subject to isolation-rearing (PIR) or social rearing (PSR) for 29 consecutive days (P21–P49). After environmental stress, mice were social-reared to adulthood. Note that juvenile social isolation elicited a significant increase in plasma corticosterone level in adult (P60).

(C) the same experimental design was carried as (B), except social (ASR) or isolation rearing (AIR) was imposed during adult (P70–P98), and blood sample was collected at P100. Note that adolescence social isolation still elicited an increase in plasma corticosterone level (A–C: unpaired Student’s t test).

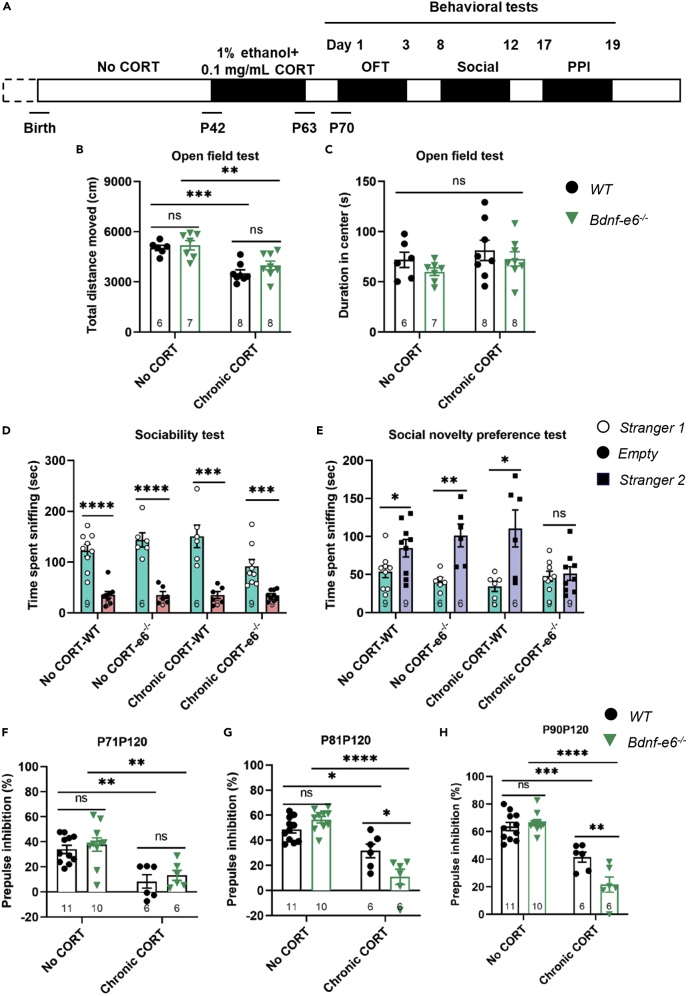

Next, we asked whether mice chronically treated with CORT (0.1 mg/kg, 22 days) (Figure 6A) could mimic stress paradigms, leading to schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes. Whereas Chronic CORT exposure (from P42 to P63) significantly decreased motor activities (Figure 6B), it did not lead to anxiety-like behavior in WT or Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figure 6C, p > 0.05). Interestingly, chronic exposure to CORT in adolescence did not impair sociability in either genotypes, but impaired the social novelty preference in Bdnf-e6−/− mice, but not WT mice (Figures 6D and 6E). Further, the same treatment also reduced PPI at prepulse intensities of 81 and 90 dBs, selectively in Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figures 6G and 6H). PPI at 71 dB after CORT treatment was so low that disruption of Bdnf-e6 could not induce any further reduction (Figure 6F). These data support the notion that blood corticosterone levels can affect the susceptibility to postnatal stress in mice, and demonstrate that chronic administration of CORT imitates postnatal stressor to induce schizophrenia-like endophenotypes in Bdnf-e6−/− mice.

Figure 6.

Juvenile CORT exposure resulted in deficient social novelty in Bdnf-e6−/− mice

(A) Experimental design. Corticosterone was administered daily from P42 to P63, and behavioral tests were performed at times as indicated.

(B and C) Open field test of WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice with or without juvenile CORT exposure. Note that “total distance moved” but not “duration in center” was significantly decreased with juvenile CORT exposure in both WT and Bdnf-e6−/− mice.

(D and E) The CORT exposure paradigm was the same as (B, C), except social behavior was measured by (D) social ability test and (E) social novelty preference test. Note Bdnf-e6−/− mice with juvenile CORT exposures exhibited normal sociability (D), but could not find differences between stranger 1 and stranger 2, suggesting deficiency in social novelty preference (E).

(F–H) The CORT exposure paradigm is the same as (B and C), except PPI was measured. Whereas both genotypes exhibited a decrease in PPI ratios after juvenile CORT exposure, Bdnf-e6−/− mice showed a further decrease at P81–P120 (G) and P90–P120 (H) (B, C, F–H: two-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. D, E: unpaired Student’s t test).

Treatment with TrkB agonistic antibody or CORT antagonist rescued PPI deficits

An obvious consequence of Bdnf-e6 disruption is a reduction of BDNF signaling in the brain. Our data indicate that Bdnf mRNA was not changed in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus after postnatal hypoxia. However, Bdnf-e6 mRNA exhibited a small but significant decrease in hippocampus (Figure S5B). Relevant to this, we found that the pTrkB levels were also slightly reduced in this group (Bdnf-e6−/− hippocampus subjected to postnatal hypoxia) (Figures S5C and S5D).Thus, we tested whether administration of an Ab4B19, an agonistic antibody that selectively activates the BDNF receptor TrkB (Guo et al., 2019; Han et al., 2019), could rescue the behavioral deficits in the GxE model (Bdnf-e6−/− + postnatal hypoxia or social isolation), using PPI as an index.

The postnatal Bdnf-e6−/− mice were subjected to either hypoxia (Figure 7A) or social isolation (Figure 7E), and a single tail vein injection of normal IgG or Ab4B19 (1 mg/kg) was given in the adult animals. Remarkably, we found that Ab4B19 could rescue the impairments in both P81P120 and P90P120 PPI, except P71P120 PPI, in the hypoxic Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figures 7B–7D). Ab4B19 could also significantly restore the PPI deficits at prepulse intensity of 90 dB in SI-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figure 7F). At 71 and 81 dB, there was a trend of the Ab4B19 effect, albeit not reaching the statistical significance (Figures 7G and 7H). These data raise the possibility that Ab4B19 could serve as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of some patients with schizophrenia in a clinic, especially those with Bdnf genetic variants (such as BDNF val/met polymorphism) or reduced blood BDNF levels.

Figure 7.

TrkB agonistic antibody rescued PPI deficiency in Bdnf-e6−/− mice exposed to postnatal hypoxia or postweaning social isolation

(A–D) Effect on hypoxia-Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Mice were exposed to hypoxia from P4 to P10, and TrkB agonistic antibody Ab4B19 (1 mg/kg) was administered intravenously 48 h hours before the PPI test (A). The normoxia-e6−/− is referred to the data from Figure 2. Note that the decrease in PPI ratio at 81 dB, 90 dB in hypoxia-e6−/− mice were rescued by Ab4B19 treatment.

(E–H) Effect on PIR-Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Mice were subject to juvenile social isolation from P21-P49, and Ab4B19 was administered the same way as A. The PSR-e6 is referred to data from Figure 3. Note that whereas there was a trend of Ab4B19 effects at 70 and 81 dB, the decrease in PPI ratio at 90dB in PIR-Bdnf-e6−/− mice was significantly reduced by the Ab4B19 treatment. (B-D,F-H: unpaired Student’s t test).

Given that postnatal stress or chronic administration of CORT elicited PPI deficits in Bdnf-e6−/− mice, we hypothesized that blockade of CORT signaling could also attenuate the SCZ endophenotype in the GxE model. To test this idea, we used mifepristone (RU-486), an 11 β-dimethyl-amino-phenyl derivative of norethindrone with a high affinity for glucocorticoid receptors proven to be an active anti-corticosteroid agent, and examined whether this drug could rescue the PPI deficits in the hypoxic or PIR-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice. We found that RU-486 significantly increased the PPI ratios in all prepulse intensity levels (71, 81, and 90 dB) in PIR-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figures 8A–8D, ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001). RU-486 could also reduce the PPI deficit in some (P90 dB), but not other (P71, P81) prepulse intensities in postnatal hypoxic Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figures 8E–8H). These data suggest that treatment with CORT antagonist rescues PPI deficits in Bdnf-e6−/− mice subjected to postnatal stress. Further, RU-486 treatment had no effect on PPI in adult isolation rearing (AIR)-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice (Figure S6), pointing to the importance of developmental stress. Interestingly, RU-486 induced a small but significant increase in PPI ratio in WT mice subjected to PIR treatment (Figure S7).

Figure 8.

RU-486 rescued PPI deficiency in Bdnf-e6−/− mice exposed to postnatal hypoxia or postweaning social isolation

(A–C) (A–D) Effect on hypoxia-Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Mice were exposed to hypoxia from P4 to P10, and daily administration of RU-486 (40 mg/kg) from P91 to P98. PPI was measured on P100 (A). The normoxia-e6−/− is referred to the data from Figure 2. Note that the decrease in PPI ratio at 90 dB in hypoxia-e6−/− mice was reduced by RU-486 treatment.

(E–H) Effect on PIR-Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Mice were subject to juvenile social isolation from P21-P49 while administered with RU-486, and PPI was measured on P100 (A). The PSR-e6 is referred to the data from Figure 3. Note that the decrease in PPI ratio at all intensities (70, 81, and 91 dB) in PIR-Bdnf-e6−/− mice was significantly reduced by the RU-486 treatment (B–D, F–H: unpaired Student’s t test).

Finally, to determine whether the RU-486 treatment could be useful in a non-genetic model, we intraperitoneally administered MK801 in the adult WT mice (Figure S8A), a widely used pharmacology model for schizophrenia. We pretreated adult WT animals with saline or RU-486 for one week, followed by induction of SCZ with MK801 (0.2 mg/kg). Treatment with RU-486 increased the PPI at prepulse 90 dB (Figure S8D). In lower prepulse intensities (71, 81 dBs), however, the PPI ratios were too low to be rescued by RU-486 (Figures S8B and 6C). Interestingly, Ab4B19 had no effect on PPI deficiency in the MK801-treated WT mice (Figure S9). This could be due to the fact that in WT mice, the level of BDNF is high already and treatment with a BDNF mimetic would bring no further benefit. Thus, RU-486 but not Ab4B19 could rescue the PPI deficits in MK801-treated WT mice, suggesting that BDNF and CORT may work through different mechanisms.

Discussion

Whereas BDNF deficiency has long been viewed as a risk factor of schizophrenia, how it works remains unclear. Our previous studies suggest that different Bdnf transcripts are expressed in different brain regions, cell types, developmental stages, and elicit different functions. Bdnf-e1 and Bdnf-e2 are involved in different aspects of obesity (thermogenesis and food intake), aggression, and serotonin signaling (Maynard et al., 2016; McAllan et al., 2018; You et al., 2020). A major function of Bdnf-e4 and Bdnf-e6 is to promote the development and function of GABAergic neurons (Jiao et al., 2011; Maynard et al., 2016; Sakata et al., 2009, 2013; Xu et al., 2021). The deficit in GABAergic neurons is one of the pathological hallmarks of schizophrenia (Dienel and Lewis, 2019), and Bdnf-e4 and Bdnf-e6 are expressed in brain regions associated with schizophrenia, such as hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus (Maynard et al., 2016). Loss of Bdnf-e4 or Bdnf-e6 leads to approximately 50% decrease in BDNF protein expression in hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus, at postnatal day 28 (PSD28), and 50%, 30%, and 30% decrease in these three areas in the adulthood, respectively (Maynard et al., 2016). It would therefore be interesting to determine whether the deficiency in Bdnf-e4 or Bdnf-e6 could account for a genetic risk for schizophrenia.

However, a schizophrenia-like phenotype has never been observed in Bdnf-e4−/− or Bdnf-e6−/− mice. The goal of this study was to investigate if and how the interaction between BDNF deficiency and early-life stress could impact the development of schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes. We employed postnatal hypoxia or juvenile social isolation (SI) paradigm in Bdnf-e4−/− or Bdnf-e6−/− mice. The main findings are that early-life stress on Bdnf-e6, but not Bdnf-e4, deficiency mice resulted in SCZ-like endo-phenotypes such as deficits in sociability and social recognition, spatial memory, and sensorimotor gating function (PPI) in adulthood. Neither early-life stress nor Bdnf-e6 deficiency alone caused these abnormalities. These results support the “two hit” hypothesis of schizophrenia, and defined a pair of genetic and environmental factors critical for SCZ pathophysiology. Interestingly, postnatal stress also increased blood corticosterone (CORT) levels of WT mice, and administration of CORT to adult Bdnf-e6−/− mice without early-life stress resulted in the same PPI deficits and social dysfunction. Furthermore, the PPI deficits in the hypoxic or SI-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice could be rescued by treatment with the CORT antagonist RU-486, or the BDNF mimetic TrkB agonistic antibody. Thus, our study also provides a potential strategy for therapeutic interventions of SCZ.

Bdnf-e6 is the major Bdnf variant expressed in the placenta (Pruunsild et al., 2007). BDNF is known to regulate placental development and fetal growth (Briana and Malamitsi-Puchner, 2018; Prince et al., 2017). Maternal BDNF has been shown to reach the fetal brain through an utero-placental barrier (Kodomari et al., 2009). Furthermore, GWAS study indicates that genetic loci of schizophrenia interacting with early-life complications are highly expressed in the placenta (Ursini et al., 2018). Therefore, it is possible that Bdnf-e6 deficiency adversely affects the placental physiology through the regulation of schizophrenia genes, impacting fetal brain development. However, we feel that maternal expression of Bdnf-e6 or NOT in placental tissues may not impact the conclusion of our study. The WT offspring generated from heterozygous breeding (+/+:+/−:−/− = 25%:50%:25%) did not exhibit any schizophrenia phenotype or macroscopic abnormality in the brain weight and size, even after an exposure to environmental stress (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). Whereas we did not specifically examine whether the absence of Bdnf-e6 in maternal placental tissues (homozygous) could cause psychotic deficiency in its offspring, the fact that Bdnf-e6−/− mice are by and large normal without environmental stress (Figure 1) indirectly suggests that placental Bdnf-e6 deficiency in maternal placenta would have minimal if any impact on the psychiatric behaviors of the offspring. Although Bdnf-e6 is highly expressed in peripheral tissues, we did not observe any macroscopic abnormity in peripheral organs of Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Another study also reported no significant difference of peripheral organ weight, metabolic parameters, insulin/glucose tolerance between WT and Bdnf-e6−/− male/female mice (McAllan et al., 2018). Thus, we suggest that the behavioral impact of environmental stress- Bdnf-e6−/− combination does not result from maternal placental or peripheral organ Bdnf-e6 deficiency, but mainly caused by abnormity in the brain.

BDNF has long been implicated in the development of SCZ (Di Carlo et al., 2019), although Bdnf gene is not located in schizophrenia-associated genetic loci based on GWAS PGC2 studies (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014). BDNF is a powerful regulator of synapses and neural circuits important for mood control and cognition, the key components relevant to SCZ (Chao, 2003; Figurov et al., 1996; Ji et al., 2010; Lohof et al., 1993; Martinowich et al., 2007; Molteni et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2000). The analysis of post-mortem brains revealed deficits in BDNF transcription and downstream signaling in the hippocampus and PFC, of SCZ patients (Reinhart et al., 2015; Thompson Ray et al., 2011). (Emamian et al., 2004; Green et al., 2011; Issa et al., 2010; Szamosi et al., 2012; Weickert et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2013; Yoshimura et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2010). Given the existence of nine main Bdnf transcripts in the brain, each with short and long 3′UTRs, it is imperative that specific transcript(s) critically involved in SCZ be defined. The association of SCZ with C270T polymorphism located in the Bdnf exon 6 has provided a hint (Neves-Pereira et al., 2005; Szekeres et al., 2003). Thus, we took advantage of the Bdnf-e6−/− mouse model that we have developed previously. Interestingly, the Bdnf-e6−/− mice per se did not exhibit any schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes. This provides an excellent opportunity for us to investigate the impact of various environmental factors on the SCZ-relevant behaviors of the Bdnf-e6−/− mice.

It is believed that a combination of genetic and early (e.g., nutritional or maternal factors) or later (e.g. social stress or drug abuse) environmental risk factors trigger the onset of SCZ. This forms the basis for the “two hit” hypothesis (Freedman, 2003; Maynard et al., 2001; McGrath et al., 2003). However, it is unclear how and when environmental stressors in conjunction with which vulnerable genes could lead to schizophrenia. In this study, schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes were led by an interplay between early development stress, either postnatal hypoxia or juvenile isolation, and Bdnf-e6−/− mice. Thus, we have identified a specific pair of GxE for SCZ: 1) not the Bdnf gene as a whole, but a specific subset: the promoter 6 driven Bdnf-e6 transcript; This opens up possibilities to investigate the role of specific brain regions, cell types, and neural circuits that Bdnf-e6 transcript is expressed or regulates; 2) environmental stress in development but not adulthood. This defines a critical time window during which the brain circuits relevant to SCZ are more vulnerable. Further studies of this GxE model may provide important insights into the SCZ pathophysiology and help develop therapeutic strategies with more precision on certain populations of SCZ patients. Finally, the approach used in this study could also be used to elucidate additional pair(s) of GxE and therefore facilitate the mechanistic study of SCZ pathophysiology.

A major challenge in schizophrenia research is the lack of animal models that could help unravel its pathophysiological mechanisms or testing new therapies. One school of thought focuses on SCZ genes identified by GWAS or genetic association studies. This is based on an assumption: an SCZ risk gene would impact some pathophysiological mechanisms, leading to alterations in symptoms/behaviors. Examples in such category include mice with mutations in Disc1 mice (Cash-Padgett and Jaaro-Peled, 2013), Dtnbp1 (Papaleo et al., 2012), Kchn2-3.1 (Ren et al., 2020), and NRG1/ErbB4 (Silberberg et al., 2006). Unfortunately, whereas these models exhibit certain “face” features, they failed to capture all symptoms or etiology of SCZ (Tordjman et al., 2007). For example, identifying these “candidate genes” requires an unbiased, genome-wide approach across diverse human populations, rather than prior biological hypotheses. Further, these genetic manipulations begin at conception to trigger various adaptive responses, which may change or preclude emergence of behavioral phenotypes. Another line of efforts emphasizes perturbations that imitate environmental stress. For example, the NMDA blocker MK801 or PCP has been used to induce hyperlocomotion and stereotypies, and to imitate some aspects of SCZ phenotypes (McKinney and Moran, 1981), such as the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits. However, the most difficult feature of NMDA hypofunction to model in rodents is the transient nature of the drug effects, which contrasts with the neurodevelopmental nature of schizophrenia (Adell et al., 2012). Animal models based on brain lesion during development are generally difficult to produce and even harder to yield consistent symptoms. For example, the injection of excitotoxins to rat ventral hippocampus during neonatal development could elicit hyperlocomotion, hypersensitivity to stimulants, disrupted sensorimotor gating, social withdrawal, impaired working memory, impaired behavioral flexibility, and addictive behavior (Brady, 2016; Lipska and Weinberger, 2000). This lesion model, however, may produce a quite general pathway of improper peri-adolescent assembly of prefrontal circuits as prefrontal networks and their responsiveness to dopamine are not normally fully developed until young adulthood (Tseng et al., 2006). The GxE model described in the present study has incorporated the two key features (GxE) relevant to SCZ and to provide a new therapeutic strategy for patients with SCZ.

SCZ remains a major unmet medical need in modern society with huge social and economic burdens (Javitt, 2014). Whereas treatments based on the dopamine hypothesis has been somewhat successful in alleviating some of the positive symptoms, they elicit significant side effects and also cannot address the cognitive deficits (Yang and Tsai, 2017). Moreover, the effects of antipsychotics are highly variable and inconsistent (Kahn et al., 2015), and these drugs do not lead to substantial improvements in social, cognitive and occupational functioning. The findings in the present study may have implications for a new therapeutic strategy. First, we have identified BDNF as one of the genetic factors and developmental stress as one of the environmental factors. Future clinical studies should examine whether these factors are indeed altered at least in some of the patients, and whether the combination of the two would exacerbate the SCZ pathophysiology. Second, the above results also point to the potential strategy for patient stratification: to select homogeneous psychiatric populations with a high blood CORT level, or alteration in BDNF (either plasma BDNF level (Heitz et al., 2019) or BDNF Val66Met polymorphism (Hashimoto and Lewis, 2006), for clinical research and therapeutic interventions. Finally, we found that the PPI deficits in the hypoxic or SI-treated Bdnf-e6−/− mice could be rescued by treatment with the CORT antagonist RU-486, or the BDNF mimetic TrkB agonistic antibody. Based on these results, one can easily think of a strategy for precision medicine. RU-486 or analogs could be employed to treat a selected group of patients with high blood CORT levels. Likewise, TrkB agonistic antibody could be administered to those with low plasma BDNF levels or BDNF-met carriers.

The present study has raised a number of important questions that should be addressed in the future. First, the neural circuits in the GxE model altered by Bdnf-e6 deficiency and stress-induced CORT should be delineated. Clues could be obtained by examining where and when the Bdnf-e6 transcript is expressed. In the present study, Bdnf-e6 mRNA is highly enriched in the hippocampus and mPFC, and dysfunction of these brain regions is involved in the pathophysiology of SCZ (Ren et al., 2020). Delivery of RU-486 or TrkB mAb should help to test whether a specific brain region mentioned above is involved. Second, it will be interesting to determine whether and which neurotransmitter systems (dopamine, GABA and glutamate) is(are) altered in the GxE model. It has well been known that altered transmissions in dopamine, GABA and glutamate are participated in the pathological mechanisms of SCZ (Ji et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2020). Third, given the difficulties in studying the SCZ positive symptoms (hallucinations and dilution) in animals, the face validity of the GxE model has not been fully established. Clinical studies should be performed in the future to test whether there is subpopulation of SCZ patients with high CORT levels or lower BDNF levels, and whether RU-486 or TrkB mAb could be useful in correcting the PPI or other SCZ endo-phenotypes.

It seems that different Bdnf exon transcripts contribute differently to a specific BDNF function. For example, the loss of Bdnf-e1 in mice results in a substantial decrease of BDNF protein levels in the lateral hypothalamus, leading to a deficit in thermogenesis (You et al., 2020). However, Bdnf-e6−/− or Bdnf-e6−/− mice also exhibit a significant decrease of BDNF protein in hypothalamus (Maynard et al., 2016), but no thermogenesis deficit (McAllan et al., 2018). It is possible that different Bdnf exon transcripts in the same brain region are expressed in different cell types, and/or targeted to different subcellular localizations (axon, cell body, or dendrites) (Baj et al., 2011; Pattabiraman et al., 2005). BDNF protein derived from different Bdnf exons may also be released at different synaptic sites (Song et al., 2017). The complexity of spatial and temporal regulation of BDNF expression, release, and TrkB signaling by different Bdnf transcripts may require further investigations.

BDNF expression can be significantly different between male and female subjects, especially under environmental stressor including maternal deprivation, social defeat, social isolation, and restraint (Bath et al., 2013). Sex differences in schizophrenia has also been described in many aspects, in terms of the age of onset, symptoms, and response to antipsychotics (Wu et al., 2013). However, the present study relies heavily on a battery of behavioral tests, especially the PPI test, which is known to be affected by menstrual cycle (PPI during luteal, compared with follicular, is relatively lower) (Jovanovic et al., 2004; Kumari et al., 2010). To obtain a stable and reliable behavioral phenotype, we deliberately eliminate female mice in this research. Whether female mice exhibit schizophrenia-like behavioral phenotype similarly to male mice under “genetic deficiency x environmental stress hits” could be addressed in the future, when better tools/technologies/behavioral assays are available for female mice.

Overall, this study illustrates that BDNF promoter VI deficiency and early-life stress together cause schizophrenia-like deficits, which could be rescued by treatment with the CORT antagonist, or the BDNF mimetic TrkB agonistic antibody. These findings provide a better understanding of how the BDNF-TrkB signaling appears to be molecular mechanism behind BDNF promoter VI deficiency and stress convergence to mediate impairment in cognition and sensorimotor gating – a defining feature of the schizophrenia-like endo-phenotypes.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we only used male mice in order to exclude the effect of menstrual cycle on animal behavior. Whether female mice under G×E hits exhibit similar behavioral phenotypes to male mice should be addressed when better tools are available, or under close monitoring of menstrual cycle. In addition, the time window for postnatal stress has not been firmly established, nor has the types of early-life stress been rigorously examined. Finally, this study used PPI as the main readout of schizophrenia-like behavior and rescuing, given the large number of animals to be tested and the need for automated quantification. A more comprehensive behavioral test should be performed before using TrkB agonistic antibody or RU-486 as a therapeutic intervention in human clinical studies.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Green Fluorescent Protein Antibody | Aves Labs | Cat# GFP-1020; RRID:AB_10000240 |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Chicken IgY (IgG) (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 703-545-155; RRID:AB_2340375 |

| GFP Antibody, pAb, Chicken | Genscript | Cat# A01694-40 |

| TrkB Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4603S; RRID: AB_2155125 |

| Phospho-TrkB Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4168S; RRID: AB_10620952 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 31462; RRID: AB_228338 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 31432; RRID: AB_228302 |

| Anti β-Actin Mouse Monoclonal Antibody | Cwbio | Cat# CW0096M; RRID: AB_2665433 |

| TrkB agonistic antibody (Ab4B19) | Guo et al., 2019; Han et al., 2019 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Corticosterone | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 235135 |

| RU-486 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M8046 |

| Tween-80 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P1754 |

| MK801 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M107-5MG |

| Tween-20 | Promega | Cat# H5152 |

| Normal Donkey Serum | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 017-000-121 |

| Triton™ X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T8787 |

| RIPA Buffer | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9806S |

| Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI | Beyotime | Cat# P0131 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) | Vazyme | Cat# R223-01 |

| AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix | Vazyme | Cat# Q111-02 |

| FastPure® Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit | Vazyme | Cat# RC101-01 |

| Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 23227 |

| SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 34080 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Bdnf-e6−/− mice | Maynard et al., 2016 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers | See Table S1 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| EthoVision XT | Noldus Information Technology | RRID:SCR_000441 |

| Xeye Startle | Beijing Macroambition | http://www.bjtmhy.com/ |

| Xcalibur 3.0.63 | Thermo Fisher | https://www.thermofisher.com |

| Tanon MP (v1.02) | Tanon | http://biotanon.com/ |

| Tanon Gis (v4.2) | Tanon | http://biotanon.com/ |

| Zeiss Zen (v2.1) | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/ |

| ImageJ (v1.52i) | National Institutes of Health | https://imagej.net/software/imagej/ |

| Graphpad Prism 8.0 | Graphpad software | https://www.graphpad.com |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Bai Lu (bai_lu@tsinghua.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Animals

Bdnf-e6 mutant mice were generated as previously reported (Maynard et al., 2016) (see Table S1 for primers for genotyping). All the mice used in this study were generated by crossing heterozygotes (e.g., Bdnf-e6 +/−) male mice with heterozygotes females. Mice were reared in the specific-pathogen free animal facility. The mice were maintained on a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, 22–26°C with sterile pellet food and water ad libitum under standard conditions.

For all tests, mice (male only, 2–4 months old) were housed with siblings, 5-6 mice per cage with mixed genotypes, except for the social isolation paradigm, in which mice were housed singly in the standard mouse cage for 4 weeks. Before testing, all mice were handled at least three consecutive days for habituation: i.e. transferred into the testing room at least 1 h before testing began. All the behavioral tests were performed during the dark phase of the circadian cycle between 09:00 and 17:00. A total of approximately 900 mice were used and sacrificed for this research.

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) and conducted in accordance of governmental and Tsinghua guidelines for animal welfare.

Method details

Animal magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetal resinence imaging (MRI) images were acquired using a 7.0T scanner (Bruker, Biospec 70/20 USR7). Before scanning, all animals were initially anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in oxygen using a chamber and subsequently maintained with 1.5–2% isoflurane in oxygen delivered via a mask. The MRI data were acquired with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2,500 ms, echo time (TE) = 136 ms, number of acquisitions (NA) = 512, number of points = 2048, spectral width = 4006 Hz.

Behavioral tests

All mice (male only, 2∼4 months old) were housed in groups, 5∼6 mice per cage with mixed genotypes, except for the social isolation paradigm, in which mice were housed in a single in the standard mouse cage for 4 weeks. Before testing, all mice were handled at least 3 consecutive days for habituation: i.e. transferred into the testing room at least 1 h before testing began. All the behavioral tests were performed during the light phase of the circadian cycle between 09:00 and 17:00.

Rotarod

Rotarod test is composed of the training sessions and a probe trial session (UGO, 47650). Before testing, mice were placed on their respective lanes and were acclimated to the rolling rod for 1 min at a constant speed of 10 rpm. In both sessions, the rotarod apparatus was set to accelerate from 10-30 rpm with a maximum trial of 80 seconds. Mice were given three trials a day with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 20 min. After three consecutive days of training, a probe trial was conducted on day 4. The mean latency to fall off of the rotarod was recorded automatically for all trials.

Open field

The open field apparatus was made up of a white acrylic box (50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm). The central zone was defined as a 25 cm × 25 cm area in the center of the box. The animals were placed in the center zone and were allowed to explore freely for 10 min. All measurements were recorded by an automated tracking system and were analyzed using EthoVision XT software (Noldus, Netherlands), including the total distance moved in the open field arena and time spent in the center zone.

Social interaction

Social affiliation and social memory were estimated via the three-chambered apparatus (60 × 45 × 20 cm). The social interaction test consisted of the sociability test and the social novelty preference test. Before the sociability test, the test mouse was placed in the apparatus and subjected to freely explore for 5 min. Then, the mouse was restricted to the middle chamber and the “Stranger 1” mouse was randomly introduced into one of two identical cages located in the side chambers. The test mouse was allowed to explore freely for 10 min after opening the doors. In the social novel preference test, a novel stranger mouse, named “Stranger 2,” was placed into the empty cage. The same test mouse again allowed to explore freely for 10 min. Note that all stranger mice used here had the same background, age, and gender as the test mouse. Throughout the entire process, the duration in each chamber and the time spent sniffing were automatically monitored by tracing video and analyzed by hand.

Morris water maze

Morris water maze (MWM) consisted of a round water tank (120 cm diameter × 40 cm depth) and a round platform (11 cm diameter × 18 cm depth). The water tank was equally divided into 4 quadrants marked with tags on the wall drawing round, square, triangle, and cross shape. Each quadrant was named with northeast (NE), northwest (NW), southwest (SW), and southeast (SE), respectively. Behavioral experiment was composed with three phases: (1) Cue phase (day 1): titanium dioxide was added into the water to make the water milky white. Water temperature and depth was set to 22°C and 25–30 cm. The platform was randomly placed into the center of one of quadrants. Then mouse was released into the water at water level (not dropped) in the desired position, facing the tank wall. Computer tracking program was started the moment that the animal was released. After the platform was reached, timer was stopped, and mouse was wiped dry and put back to homecage. Mice unable to find the platform were eliminated, due to their potential abnormally of swimming ability or eyesight. (2) Acquisition phase (day2–7): After 24 h of cue phase (day 2), mouse was released into the water (water depth 30–45 cm) with a platform placed in SW quadrant, movement locus within 60 seconds was recorded. If mouse could not reach the platform within 60s, experimenter would guide it to the platform, and let stay on the platform for 15–20s. If the mouse successfully reached the platform but unable to stay on the platform, experimenter would also guide it to stay on the platform for 10s. After the experiment, mouse was wiped dry and put back to home cage. Each mouse was trained 4 times a day, with 20–30 min inter-trail interval. The acquisition phase was continued for 6 days. Start position for each trail was listed in the table shown below. Water should be replaced every 2–3 days to eliminated odor disturbance. Average time spent on successful platform reaching for each day was calculated. Note shorter time spent on successful platform reaching represents better spatial learning. (3) Probe phase (day 8): Mouse was released into the water tank at NE quadrant, with no platform inside the tank. Movement locus within 60s was recorded. Time spent in each quadrant, times crossing presumed platform position, and time spent successfully to locate the presumed platform for the first time were analyzed. Note that more time spent in presumed platform quadrant (SW), more times crossing presumed platform position, and shorter time spent for successful platform location represent better spatial memory.

| Training day | 1st trail | 2nd trail | 3rd trial | 4th trail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st day | random | |||

| 2nd day | N | E | SE | NW |

| 3rd day | SE | N | NW | E |

| 4th day | NW | SE | E | N |

| 5th day | E | NW | N | SE |

| 6th day | N | SE | E | NW |

| 7th day | SE | NW | N | E |

| 8th day (probe phase) | NE | |||

Prepulse inhibition

The prepulse inhibition (PPI) test was measured using the Xeye Startle Reflex System (Beijing MacroAmbition S&T Development Co.,Ltd, China). Here, the PPI test consisted of three phases. In the acclimation phase, the test mouse was restricted to an open-air cage and then placed into a chamber without any startle stimulus for 15 min on the day before testing. On the testing day, the session began with a 5-min habituation period, followed by two types of stimulus trials presented in a pseudorandom order: (1) pulse-alone: 120 dB (40 ms duration) stimulus and (2) prepulse-pulse: 120 dB stimulus (40 ms duration) preceded by the 71, 81 or 90 dB prepulse (20 ms duration). Each trial was performed for ten times with a variable inter-trial interval (ITI) ranged from 15 s to 20 s. Additionally, a 65-dB background noise level was given throughout the entire testing period to avoid the effects of noise outside of the startle chamber. The PPI was calculated as a percentage score for each prepulse-pulse trial type: %PPI = [(startle amplitude of pulse-alone trial-startle amplitude of prepulse-pulse trial)/startle response in the pulse-alone trial] ×100.

Novel object recognition

Novel object recognition test was performed as described previously. The experimental apparatus was made up of a white acrylic box (31 × 31 × 20 cm). The object-recognition tasks consisted of three phases. In the first phase, the subject mouse was put into an empty open field that differed from the home cage and was given a 5-min habituation period once a day for three consecutive days. In the acquisition phase, the subject mouse could freely explore two identical objects located 5 cm away from the wall for 5 min. Before the retention phase, the mouse was returned to its home cage for a retention period (5 min or 1 h), and the two objects were removed. During the retention phase, the subject mouse was again put into the open field and could explore an object identical with the original one (the “familiar” object) and a novel object for another 5 min. Throughout the entire process, the exploration time of all trials was manually recorded blind to the treatment. The discrimination ratio in the retention phase was calculated using the following formula: [(time spent exploring the novel object - time spent exploring the familiar object)/total exploration time]. Four cohorts of male mice (about 12-week-old) were used in the NOR test.

Nest building

Nesting was measured in home cage. Before experiments, all nest building materials, including hay, twine, wood-chip, were removed from the home cage. One hour prior to the dark phase, mice were separate individually into the home cage with absorbent sponges as nest building materials. Nests of each mouse were assessed next morning on a rating scale of 1-4, according to Figure S3A.

Environmental stress

Postnatal hypoxia paradigm

Heterozygous (Bdnf-e6+/− or Bdnf-e4+/−) parents were used for breeding. Litters and their genetic mothers were randomly housed in either normoxia or hypoxia condition with access to food and water ad libitum. During hypoxic period, pups and adult mice were nursed in a Plexiglas chamber (BioSpherix #A-30274-P, Ltd., Lacona, NY) with a nitrogen (N2)/ compressed air gas delivery system that mixes the N2 with room air using a compact oxygen controller (BioSpherix, Ltd., ProOx P110). Mice were exposed to hypoxia (O2 level 10%) or normoxia (O2 level 21%) for 6 days (P4∼P10 neonatal stages or P70∼ P76 adult). At the age of three weeks, male litters were separated from females, and their genotypes were identified by PCR. Bdnf-e6/e4 homozygous male mice and WT male littermate control were used for further experiments.

Social juvenile isolation

Heterozygous (Bdnf-e6+/− or Bdnf-e4+/−) parents were used for breeding. Male mice were housed in isolated ventilated cages (maxima six mice per cage) barrier facility at Tsinghua University. At weaning (PND 21), with Bdnf-e6−/− and WT mice randomly assigned to the isolation-rearing (IR) condition (1 mouse per cage) or the social-rearing (SR) condition (4-5 mice per cage) for 4 weeks (PND49), assuring that mice with different genotype were equally housed in each SR condition. Mice in all cages were reared under the same conditions (12/12-h light/dark cycle and 22–26°C) and received sterile pellet food and water ad libitum, so that IR mice could still see, hear and smell other mice without having physical contact.

Blood corticosterone measurement

Orbital blood samples (500 μL) were collected into a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes, standing still at room temperature for 45 min, with subsequent centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Upper layer serum was transferred to new 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube. Pre-chilled high-performance liquid chromatography–grade methanol (at −80°C) was added to the tube according to the volume of serum, with 400 μL methanol per 100 μL serum. Mixed liquid was gently homogenized by hand shaking for 1 min, and incubated at −80°C for 2 h. After −80°C incubation, sample was centrifugation at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was further lyophilized to powder with Speedvac (Thermo Savant SPD1010). The dried sample was used for corticosterone measurement or stored in a −80°C freezer. The ultra-performance liquid chromatography system was coupled to a Q-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, CA) equipped with a APCI probe. For corticosterone analysis, extracts were separated by a Biphenyl 150 × 2.1 mm column. A binary solvent system was used, in which mobile phase A consisted of 100% H2O, 0.1%FA, and mobile phase B of 100% CAN containing 0.1%FA. A 10-min gradient with flow rate of 350 μL/min was used. Column chamber and sample tray were held at 40°C and 10°C, respectively. Data with mass ranges of m/z 300–400 were acquired in positive ion mode. The full scan was collected with resolution of 70,000. The source parameters were as follows: Discharge current 6μA; capillary temperature: 320°C; heater temperature: 400°C; sheath gas flow rate: 35 Arb; auxiliary gas flow rate: 10 Arb. To calculate the absolute value of blood corticosterone content, 200 μL 100 μg/mL corticosterone diluted by HPLC-grade methanol was used as standard sample. Data analysis and quantitation were performed by the software Xcalibur 3.0.63 (Thermo Fisher, CA).

Drug treatment

Corticosterone chronic treatment

Corticosterone was firstly dissolved by 100% ethanol, and further dissolved into mice drinking water to 1% ethanol concentration and 0.1 mg/mL corticosterone. Drinking water bottle was fully covered by silver paper and changed every 3 days, in case corticosterone degraded overtime. For control group mice, drinking water only contained 1% ethanol.

RU-486 chronic treatment

RU-486 was dissolved with 100% Tween-80 and 0.9% saline into 10 mg/mL, with 1% Tween-80 in the final working solution. Mice treated with RU-486 were intraperitoneal injected with 40 mg/kg RU-486 (4 μL/g working solution) once a day for 8 consecutive days. For control group mice, 1% Tween-80 dissolved in 0.9% saline were intraperitoneal injected at 4 μL/g.

TrkB agonistic antibody treatment

Adult Bdnf-e6−/− mice undergone postnatal hypoxia or social isolation and MK801-treated WT mice model were treated with a single tail vein injection of Ab4B19 (1 mg/kg) 48 h before PPI test began. For control group mice, saline or normal IgG (1 mg/kg) was injected through the tail vein. Details of MK801-treated model are listed below.

MK801 treatment

MK801 was firstly dissolved and diluted to working solution (concentration at 10–4 mM/mL) with saline. Adult WT mice were treated with MK801 intraperitoneally (0.2 mg/kg) 30 min before PPI test began.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated and extracted from targeted frozen tissues using Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme) following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop (Denovix), and then RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme) following the recommended protocol. See Table S1 for primer information for RT-PCR.

Western blotting

Dissected brain tissues from each mouse were homogenized by grinding in 1 mL of chilled RIPA lysis buffer. After centrifugation for 30 min at 17,000 g at 4°C, supernatants were then collected, and protein concentrations were measured by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Thereafter, total protein concentrations were denatured at 95°C for 10 min. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis using a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto activated PVDV membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore). Membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in 0.1 M tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. and then incubated in primary antibody dilution buffer overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated in secondary antibody dilution buffer for 2 h at room temperature. After TBST washing, membranes were detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) by Tanon 5,200 (software: Tanon MP, v1.02) and analyzed using Tanon Gis (v4.2). The primary antibodies used were anti-GFP (1:500, Genscript, A01694-40), anti-TrkB (1:1000, CST, 4603S), anti-pTrkB (1:1000, CST, CST, 4168S), anti β-Actin (1:2500, Cwbio, CW0096M).

Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were deeply anaesthetized with Avertin and transcardially perfused with PBS (pH7.4), and fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The brains were dissected and post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4 °C followed by 40-μm-thick coronal sections cut using vibratome. The free-floating sections were fixed again by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 15 min and washed with PBS three times for 15 min at room temperature, followed by blocking in 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS overnight at 4°C. Then, sections were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day, the sections were washed by PBS three times for 15 min at room temperature and then treated with secondary antibody overnight at 4°C. Finally, the sections were washed three times in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and mounted on slides with mounting medium (with DAPI) and coverslipped. Slides were scanned on a microscope Axio Scan.Z1 (ZEISS) for imaging, and images were analyzed with Zeiss Zen (v2.1) and ImageJ (v1.52i). Primary antibody for immunostaining was GFP (1:1000, AVES, GFP-1020) and secondary antibody was donkey anti-chicken IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 703-545-155).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Unpaired Student’s t-tests were performed for social interaction, Morris water maze, prepulse inhibition, novel object recognition, blood corticosterone measurement and relative mRNA expression. Two-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used to analyze open field, rotarod, prepulse inhibition, novel object recognition, nest Building and body weight. In multi-bar figures, statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance followed by a post hoc test. The number of animals used for each test was shown in the bar graph or as indicated. Sample size was based on the similar published research, to ensure adequate statistical power. In addition, the sample sizes for each experiment have been detailed in the figure legends and confirmed statistically by appropriate tests. Genotyping data were not blinded, but were re-checked by different investigators. Western blotting was done and data analyzed by different investigators. For morphological analyses, data collections were performed together in a shared microscope and the conditions were blinded for each experiment.

All statistical analyses were performed using software GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ns, not significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0126500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81861138013, 81501105, 31730034), and funds from 4B Technologies (Suzhou) Co. Ltd. We are grateful to Dr. Dai Zhang (Peking University Sixth Hospital, Beijing, China) for providing professional suggestions to this study, Dr. Yonghe Zhang (School of Basic Medical Science Peking University, Beijing, China) for coaching us with PPI behavioral test, and Yujing Bai (Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China) for providing hypoxia housing chamber for pilot experiments.

Author contributions

Y.C. and B.L. designed the study. B.L., F.Y., and Y.C. wrote the paper. Y.C. and S.L. performed and analyzed most of the experiments, including the total behavioral test, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry corticosterone measurement. T.Z. helped with the PPI experiments. Y.C., S.L., and T.Z. contributed intellectually to the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

B.L. and Y.C. are co-inventors of a pending patent application on a medicinal product for treating schizophrenia.

B.L. is a co-founder and Scientific Advisor for 4B Technologies, (Suzhou) Co. Ltd, and BioFront, Ltd, biotech companies that develop medicines for various diseases.

The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 15, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104609.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

All the data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Addington J. The promise of early intervention. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1:294–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adell A., Jimenez-Sanchez L., Lopez-Gil X., Romon T. Is the acute NMDA receptor hypofunction a valid model of schizophrenia? Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38:9–14. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aid T., Kazantseva A., Piirsoo M., Palm K., Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]