Abstract

Rapid economic stimulus in response to COVID-19, typically based on ‘shovel-ready’ infrastructure, has opened up new political spaces of hope to ‘Build Back Better’ and transform economies. This research seeks to link the public ‘taking place’ of hope, representing the aspirations of various groups for investment or change stimulated by this fund, with the less visible ways governments ‘organise’ hope, the expert, technical processes and rationalities that help determine which hopes become realised and why. Using the Aotearoa New Zealand ‘shovel-ready’ fund as a case study, and drawing upon press releases, media, Official Information requests, and Cabinet documents, we first provide a discourse analysis of the various government and non-government hopes that became attached to this stimulus. We then trace how these became translated into project proposals, before unpacking and analysing the urgent processes developed to assist political decision makers. While crises and hope can be positioned as having significant disruptive potential, we reveal how this was stifled by the technical processes and practices of the processual world enacted at the national scale, which was given significant power. Further, although public discourses reflected a plurality of multi-scalar and temporal hopes for investment, in practice the less visible organisation privileged a much more business-as-usual approach. Consequently, any government aspirations for transformation were rendered less likely due to the processes they themselves established. Overall, we emphasise the need for those committed to reform to bring technical processes and rational practices to greater prominence in order to reveal and challenge their power.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hope, Infrastructure, Economic stimulus, Crisis, Decision making

1. The hope of COVID-19 and ‘building back better’

We will build back better from the COVID crisis. Better, stronger, with an answer to the many challenges New Zealand already faced. This is our opportunity to build an economy that works for everyone, to keep creating decent jobs, to up-skill and train our people, to protect our environment and address our climate challenges, to take on poverty and inequality, to turn all of the uncertainty and hard times into cause for hope and optimism. It’s an opportunity we have already grabbed and a plan we have laid out to invest in the infrastructure. It sets us up for generations to come while creating thousands of jobs”. Jacinda Ardern, election victory speech, Oct 17th 2020.

Pandemics, like other societal shocks or disasters, are times of crisis, disruption, and emergency action. There are dramatic changes to how people live, work, and communicate. Financial or policy measures that may have been unthinkable previously can quickly become mainstream. And, as the opening speech from New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern emphasises, crises like COVID-19 present opportunities for more radical action. Disruption to the normal discourses and priorities of politics, or taken-for-granted budgetary constraints, serve to open up new public imaginaries, advocacy coalitions, or transformative possibilities, such as restructuring national economies to be less unequal or infrastructure investment to be centred on quality of life or climate change.

A recurring discourse associated with this pandemic has been focused on the potential ‘hopes’ associated with stimulus investment. Not just that rapid state intervention will support jobs in the short-term, but how the crisis provides an opportunity to ensure the future is better than the present. To this end we have seen the ‘Build Back Better’ leitmotif rise to occupy a lofty political position in countries such as the US, UK, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as within institutions like the World Bank or the OECD (Bodewig and Hallegate, 2020, Oecd, 2020). The discourses of hope and hopefulness associated with these public spending programmes have stimulated new imaginings of what the future could hold, provided insights into the dissatisfactions of the present, as well as a tangible mechanism around which multiple hopes emerge and co-exist in the 'not-yet become' (Bloch, 1986: 188). At least for a short while.

As these discourses of hope are interwoven with desires for an urgent government response, for COVID-19 this interlude of possibility is particularly truncated. A swathe of emergency decision making processes have been rapidly established to help organise and allocate funds, many of which bypass typical democratic processes by drawing upon the expertise of technical panels to act more swiftly and ‘fast-track’ decisions (Anthony, 2020, McLean, 2020). As such, just as hope has quickly emerged, so may disappointment, but this time in a less transparent and democratic manner. As Anderson (2006a: 144) observes: “Hope is easily identified and its quantitative presence or absence highlighted, but the taking-place of hope, its mode of operation, remains an aporia”.

This paper draws upon press releases, media, Official Information requests, and Cabinet documents to, first, identify and interrogate the various discourses of hope that were stimulated by the announcement of a ‘shovel-ready’ economic stimulus fund in Aotearoa New Zealand. The political context setting the scene for the emergence of Build Back Better is important to note. While neoliberal policy reforms have long been a feature of national politics (e.g. Boston et al., 1996), in the years prior to COVID-19 this agenda had culminated in an ideational hegemony around the notion of an ‘infrastructure deficit’, which political parties agreed was contributing to a wide range of societal ills, such as housing unaffordability, congestion, lost productivity, and poor mitigation and adaptation to climate change (Walls, 2019). The link to decision making practices, in particular inefficient planning, was also positioned as a central cause. In addition to ongoing policy reforms aimed at speeding up decision making, the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission was established in 2019, which explicitly positioned new infrastructure as central to both economic performance and wellbeing.

The projects submitted to the shovel-ready fund also emerged into a political environment that had been re-invigorated since the election of the Labour-NZ First coalition government in 2017 and enhanced following a landslide election win in October 2019 for the Labour government. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s cultivation of a ‘kinder’ politics had been threaded with messages encouraging hope for transformational change on issues such as climate action and child poverty (Ardern, 2019; Roy & Graham-McLay, 2020) or by announcing the world’s first ‘wellbeing budget’ (Roy, 2019). As a consequence, there has been much focus both nationally and internationally on how the Government could match their hopeful and aspirational political rhetoric to practical action.

To understand why change is difficult and to seek to hold rhetoric to account, we draw on work from Anderson and Holden, 2008, Anderson, 2006a, Anderson, 2006b, and Inch et al. (2020) to construct an analytical frame that captures both the ‘taking place’ of hope and the ‘organisation’ of hope. The former is typically stimulated by a hopeful ‘event’ (e.g. Build Back Better funding) and relates to the public aspirations of various groups for investment or transformation. The ‘taking place’ of hope can draw upon current disappointments and the openness of the event to express new articulations for the future. The ‘organisation’ of hope refers to the technical processes and rationalities of governing that determine which hopes become realised and why. This tends to draw upon existing expert groups and established practices that filter, assess, and privilege possible futures. Our key message is that while a diverse array of public hopes emerged in response to the possibilities of investment, including from the Government itself, the more opaque technical processes designed to organise these held the real power. We therefore highlight the importance of understanding the ways through which the ‘operation’ of hope, and its reliance on centralised, expert calculative practices, particularly during periods of crisis, establish the boundaries of what futures are considered possible.

As Bloch (1998: 339) highlights, while life is full of ‘castles-in-the-sky’ dreams that are unlikely to be realised, so may ‘well founded’ hopes flounder: “how often has [public activism] tried to swim without getting near the water?’ How often has youth, and not only youth, been seduced by the pied piper?…[and] How much passion was invested in such hopes?” It also implies another question, which we grapple with at the end: how can those committed to reform and change bring to light those powerful processes and practices during periods of crisis response, which do not just disrupt normal politics, but normal processes of decision making as well.

2. Situating the politics of hope and its organisation

Hope for an alternative future is central to many political struggles for equality and action (Anderson, 2006b, Head, 2016, Kleist and Jansen, 2016). Scholars frequently draw attention to how hope is seen as a positive compared to the catastrophism, pessimism, and associated lack of agency that can pervade much crisis discourse, whether about climate change, biodiversity collapse, or the power of capitalism (Coutard and Guy, 2007, Solnit, 2016). Head (2016) provides further insight by emphasising how, in contrast to optimism and its implicit trust in modernity to address crises, hope is more action-oriented and can challenge power by encompassing a wider array of voices, politics, and practices. Eagleton (2015) similarly highlights the importance of power relations in distinguishing between optimism and hope. He argues optimism is a typical component of a ruling-class ideology that has an implicit faith in the soundness of the present to deliver a desired future, while hope is a virtue that better recognises the unjust nature of reality and is more subversive by acknowledging struggle. As Amin & Thrift (2002: 4) put it, hope is “a firm belief in the actualities of change that can arise from the unexpected reaction to the vagaries of urban life, the novel organizations that can arise, and, in general, the invention of new spaces of the political”.

From this perspective, hope represents both a resource and an opportunity to develop new imaginaries or ontological framings that are less hierarchical, more diverse, and with explicit links to grassroots mobilizations (Cameron and Hicks, 2014, Dinerstein and Deneulin, 2012, Gibson-Graham, 2008). Drawing upon wider literature, we position hope as a type of space–time relation with multiple dimensions (Anderson and Holden, 2008, Bloch, 1986, Zournazi, 2002). Hope is multi-scalar as it cannot be separated from national contexts, the reality of living in a globalised world with huge disparities, or individual experiences, injustices, and resistance. Hopes are therefore temporal too: linked to the uneven nature of the present as well as the “potentiality and uncertainty” of the future (Kleist & Jansen, 2016).

In his seminal text Bloch (1986: 8–9) emphasises this temporal dimension by describing hope as ‘forward dreaming’ of the ‘not-yet-become’ and as a reaction against ‘what-has-become’. He suggests hope represents a collapsing of past and future, and a re-politicising of the various dissatisfactions of the present where an “unbecome future becomes visible in the past, avenged and inherited, mediated and fulfilled past in the future” (Bloch 1986: 8–9). Here, we gain insights into how crises and hope can disrupt existing space–time relations, such as between the present and future, global and local, or status quo and transformation. It fosters the possibility of an open, if indistinct, future and in conjunction with crisis response, importantly one bound up in a sense of urgency, resources, and action. Davidson (2021: 433) however, draws upon Bloch to temper some of this optimism, emphasising that hope is inevitably co-constituted with disappointment, which: “pulls in two directions simultaneously, at once prospective and retrospective” as we look backward to interrogate past failed hopes, and in doing so influence new hopes of the not-yet-become.

Crisis claims can similarly be positioned as provoking political moments that may react against either an imagined future threat or the experiential past and present. Disruption from crises represents a breakdown of “familiar symbolic frameworks that legitimate the pre-existing socio-political order” (Boin et al. 2008: 3). This dynamic opens space for “hegemonic struggle” (O’Callaghan et al. 2014: 124) that can unsettle the status quo and stimulate demands for action, typically by national governments (Adey et al., 2015, Anderson, 2016). Crises may therefore draw upon existing disappointments to invoke new hopes that hold the potential for change (Anderson 2016). This opportunity to ‘forward dream’ new imaginaries can also provide an important sense of agency that aids coping in the present (Anderson, 2006a). Both hope and crisis then present opportunities for disrupting hegemonic imaginaries of what is possible (Cretney, 2017, Luft, 2009). Consequently, the disruption associated with COVID-19, especially when combined with significant economic action, opens a multiplicity of important political spaces for change that can become occupied with various hopes from various actors and agencies, each of which may envision radically different futures (Castree, 2010, Harvey, 2000).

However, not all agree that the possibility for hope to generate pluralistic visions of possible futures is realistic, particularly when considering the role of political and economic power in its subsequent organisation. For example, in a parallel that echoes the hopeful messaging of Build Back Better from COVID-19, Berlant (2011) highlighted how the feelgood promise of Obama’s “Yes We Can!” strain of emotional political optimism stood in contrast to both his limited sovereignty as a transformative agent, as well as the curation and maintenance of the kind of solidaristic politics able to challenge embedded power structures and social relations. Chandler (2019: 698) also discusses how some theorists have positioned hope as redundant under the conditions of the anthropocene, something “problematic and increasingly reactionary as its impossibility becomes clearer.” Tsing et al. (2019) expand on this theme, questioning whether it is possible to hope in these contexts given it was the modernist drive for progress that built the very crises we are confronted with. They argue that hope is frequently focussed on either defensive imaginaries of protection and isolation in the face of cascading threats, or a type of ‘zombie hope’, a technologically driven future that represents a green hangover of modernism.

This argument emphasises the role of fear in understanding how hopes can coalesce around stability rather than transformation and favour those with power rather than those without. As Anderson (2006a: 734) reminds us, the taking place of hope reflects the future as “open to difference” and the present, in the words of Gibson-Graham (1996: 259), as “uncentered, dispersed, plural and partial.'' If future hopes, particularly as an antidote to fearful imaginaries, coalesce around a desire to maintain normality, recover, or be ‘resilient’ in the face of disruption, this plurality may be stifled. As Swyngedouw (2010) discusses in relation to climate change, fear can be used to craft depoliticized imaginaries of possible futures that rely heavily on managerial and technocratic solutions. As such, fear can depoliticise the scope of hope as well as the processes by which it is organised; to foreclose rather than open spaces in which different visions for the future can be imagined (Kenis and Mathijs, 2014, Swyngedouw, 2010).

Power, politics, and processes are therefore central to understanding not just how hopes are framed and articulated, but also their possibility of being realised. Hage (2003: 3) positions societies, and specifically the state, as “mechanisms for the distribution of hope”, a situation that is exacerbated under conditions of crisis and urgency. However, in research that focuses on Australia he argues distribution is shaped by a culture of worrying that has been institutionalised, one that reproduces capitalist imaginaries, neoliberal economic policy and a paranoid nationalism that fosters threats to be defended against as well as hopes to be aspired to. It emphasises how societies distribute hope unequally, privilege certain hopes over others, and use fear to catalyse action against possible futures where an ‘other’ represents a threat to normality (Sparke, 2007).

Inch et al. (2020) provide further detail on how hopes need to become ‘organised’ via the existing technologies, practices, and capacities of the processual world, which may be in tension with the more malleable and imaginative ways hope becomes visible. In other words, to achieve change, the organisation of hope needs to be reconciled with the different modes by which hope becomes expressed by communities, the varying temporalities of desire, uneven power relations, or constraints of engagement processes (Baum 1997). Consequently, the framing of crisis response holds organisational power by establishing the terrain upon which hopes are shaped and decisions made. For example, the ‘Build Back Better’ discourse may logically lead to a strong focus on infrastructure and growth. Carse and Kneas (2019) describe logics like these as a form of ‘promissory note’, where investments in the physical landscape are claimed to lead to investment returns, as well as beneficial social and economic changes. However, this broad promise needs to be considered alongside the emerging critique of ‘Building Back Better’ (Black, 2020, Der Sarkissian et al., 2021, Fernandez and Ahmed, 2019). The ‘build’ element signifies a materiality dimension that accords with notions of modernity, ‘back’ suggests a return to normality rather than transformation, while ‘better’ is slippery and vague (Der Sarkissian et al., 2021). Together ‘Build Back Better’ runs the risk of becoming a postpolitical slogan inseparable from neoliberal discourses which privilege a future similar to the present, one focussed on ‘what-has-become’ and investment that benefits those with resources than those without (e.g. Cheek & Chmutina, 2021). More insidiously, the framing masks the close relationship between neoliberalism, inequality and vulnerability, such as how COVID-19 “exposed, exploited and exacerbated global health insecurities co-produced by neoliberal policies and practices” (Sparke and Williams, 2022: 26).

Therefore, while Build Back Better holds potential to attract a plurality of hopes and an open future, it sends signals that indicate how these hopes should be organised in the processual world. Frames like these give power to certain types of knowledge, expertise, and rationalities within the decision making process. For instance, infrastructural investment decisions align to an existing economic and procedural rationality that also privileges expert knowledge, calculative practices, and technical professions. These ‘authorised acts of seeing’ (Jasanoff 2017) provide legitimacy and authority to decision making, and so the public taking place of hope becomes mediated by its less public organisation, such as the politics of data availability, or the current ideational hegemonies or existing ways of knowing and doing (Jasanoff, 2004, Latour, 1999). This relationship is further complicated under conditions of crisis given both its “complex mix of financial and time pressures” (MacAskill, 2019: 1) and the tendency to extend government powers or draw upon expert elites to ‘fast-track’ decisions in ways that are in tension with more deliberative and participative decision making (Swyngedouw, 2018).

This discussion has emphasised the aspirational ‘taking place’ of hope is situated within a multi-scalar and multi-temporal context that reflects upon current and previous dissatisfactions. Literature pertaining to the ‘organisation’ of hope is more directed towards interrogating the power of influential actors and agencies and the technical processes that will eventually determine which hopes will be realised and why. Together these provide an analytical frame able to link the opportunistic nature of crisis response, and the reopening of past, present, or possible futures, with economic rationalities, existing ideational hegemonies and the power of the state. This theoretical scene setting also situates the public taking place of hope following a crisis with its less visible emergency operation, where the organisation of hopes through criteria and expert assessments will bring disappointment for many.

3. Methods

To explore the complexity and nuance of the organising and taking place of hope, we focus on one aspect of the wider New Zealand Government COVID-19 response and recovery: the $3 billion ‘shovel ready’ infrastructure fund. This programme was allocated funding early on in the pandemic as part of the May 2020 budget and the $50 billion ‘Covid Response and Recovery Fund’ (CRRF). The approach we took sought to capture both the emotional, aspirational ‘taking place’ of hope expressed in the public sphere, as well as more investigative, detailed work that was designed to piece together how these hopes were organised in practice. This stage was by far the more difficult of the two due to its opaque and emergency nature.

For the former, a comprehensive search of parliamentary media releases was undertaken to collect all releases by Ministers on the subject of shovel ready infrastructure projects. Press releases were gathered through searching the parliamentary database using the terms “infrastructure”, “shovel ready” and “COVID-19 recovery” for press releases between the 1st of March 2020 and the 31st of December 2020. We also gathered selected news articles published in the same time period from the main political New Zealand media outlets: Stuff.co.nz, Radio New Zealand, Scoop.co.nz, Newshub, New Zealand Herald, The Spinoff, and Newsroom that related specifically to the decision-making process undertaken for the shovel ready fund. These articles were found through website specific searches using the keywords “COVID-19 recovery” and “infrastructure” or “shovel ready.” In total we collected 58 Government press releases and 66 other media articles.2

For the latter, we undertook a search for publicly available government documents relating to the shovel ready infrastructure fund. This included the application form and wider information provided by the Information Reference Group, Department of Internal Affairs briefings, and associated documents such as presentations by interest groups, as well as all parliamentary written questions relating to the shovel ready fund. We then requested further document sources through the Official Information Act 2002. Our request for information was made to the Infrastructure Reference Group, the Treasury, the Minister for Infrastructure and the Minister of Finance. The request covered documents relating to Cabinet decisions for the shovel ready fund as well as documents relating to the wider decision-making process. From these sources we obtained and analysed 41 government documents.

All documents, including OIA release documents, parliamentary press releases and media articles, were then imported and coded thematically with the aid of Nvivo software. The data were first read and re-read to develop overarching themes (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Themes developed include the rationalities of prioritisation in the decision making process, the role of urgency, and how decisions were made by the Infrastructure Reference Group and Ministers. Further coding of the media and document data was carried out to refine this analysis. From this coding, the core theme of hope for change, and its various multiplicities, were developed as central to the political narratives constructed around the pandemic recovery. We then carried out an iterative process of re-analysing the data to bring to light the discourses associated with the theme of hope.

We understand discourses as ensembles of “ideas, concepts and categorizations that [are] produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities” (Leipold et al., 2019: 448). The representation and communication of aspirations, goals and possible futures through document and media sources allows for insight into the processes of hope in both the political and public sphere. This approach fits with an understanding of hope not as “an individual act” rather something that emerges from “sets of relations and encounters that make up the processes of hoping.” (Anderson and Fenton, 2008: 78). Interrogating discourses of hope then allows for an insight into these complex and ever-shifting relations and encounters, including our aim to grapple with the taking place and organisation of hopes in the face of crisis.

We now turn to our analysis of the discourses of hope that emerged from the Aotearoa New Zealand COVID-19’shovel ready’ fund. We discuss how these hopes were organised and prioritised, before turning our attention to the emergency politics, powers and decision making practices that determined which would be realised and why.

4. Raising and organising hope

4.1. Announcing Hope

As the scale of the pandemic became apparent, the Government acted quickly to provide hope and reassurance. On the 17th March 2020 it became one of the first globally to announce a stimulus package, which at 4% of GDP was bigger than Australia’s (1.2%), Britain’s (0.6%), Ireland’s (0.9%), or Singapore’s (1.3%) (Graham-McLay, 2020). In the May 2020 budget the government formally established a $50 billion Covid Response and Recovery Fund. The ‘shovel ready’ fund, as part of the CRRF, was announced on the 1st April 2020, aiming to fund public and private sector projects that had the capacity to be up and running in six months (PPR1). The fund was positioned as a means to stimulate and organise hopes over multiple times, scales, and publics, providing both an urgent response to fear of an economic crisis, as well as aiming to address long-term challenges. These fears were high-profile, as projections of a significant economic downturn, particularly in tourism and construction, painted a grim picture. For example, in May 2020 advice from an economic consultancy forecast an “8% contraction in economic activity” in 2021, which was likely to result in the loss of over a quarter of a million jobs and push unemployment rates into double digits (DOC3). The flurry of announcements outlining the broad scale and scope of investment in response created a fertile wave of hopes within both government and the public.

The fund embodied the government’s hope of getting “money out the door quickly to stimulate the economy and prevent unemployment” (MED9), while simultaneously positioning new infrastructure as key to Government aspirations to transform society and the economy. For instance, the parliamentary press release accompanying the fund announcement, stated “projects will help address the country’s infrastructure deficit as well as create jobs and buoy the economy” (PPR1). As Minister David Parker described, the fund, combined with parallel moves to ‘fast-track’ planning for selected projects, aimed “to help create a pipeline of projects, some that can start immediately [once] restrictions are lifted, so people can get back into work as fast as possible” (PPR2). Government hopes were also communicated to applicants via the fund guidelines, which outlined interest in projects that “modernise the economy” and “enhance sustainable productivity” rather than “replicate current economic arrangements” (DOC6). The focus on transformation was further emphasised in a Cabinet Paper on the fund:

“We are also focused on investing in the direction that we want New Zealand to move towards in the future - transitioning towards a more productive, sustainable and inclusive economy, enabling our regions to grow and supporting a modern and connected New Zealand” (DOC3).

Later, in her October 2020 election victory speech, Prime Minister Ardern tightly linked this infrastructure investment to the opportunity to: “…build back better from the COVID crisis. Better, stronger, with an answer to the many challenges New Zealand already faced” (Ardern, 2020). The fund then signalled ambitious government hopes for transformation, as well as short-term job creation and stability, with a clear infrastructural promise to the framing of hope. Drawing upon data from press releases, government documents released through the Official Information Act 2002, and media reports, Table 1 outlines two dominant discourses of government hopes and their subordinate sub-themes that emerged from the ‘shovel ready’ fund: economic prosperity and environmental change. You can see how various ministers all tried to advance their own hopes for priority investment.

Table 1.

Key Central Governmental discourses and themes during the ‘taking place’ of hope.

| Key discourses | Themes of hope | Examples of hope articulated by Central government |

|---|---|---|

| Economic prosperity | Providing jobs | “Every dollar we have invested we have invested to create jobs. Jobs that provide people with a good day’s pay, doing meaningful work building a better future for New Zealand.” Associate Finance Minister James Shaw (MED10) |

| Re-invigorating the regions | “We are changing gear to give greater certainty in how the Government will leverage its balance sheet to invest in infrastructure that will support regional and local economies.” Minister for Local Government Nanaia Mahuta speaking to the 2020 Stormwater conference (PPR6) | |

| Addressing housing affordability | “This project is a great example of a shovel ready project that will unlock urban development and lead to the building of more public and affordable housing” Minister for Urban Development Phil Twyford (PPR5) | |

| Economic transformation | “Ministers will be particularly interested in investments that modernise the economy and set it up to enhance sustainable productivity into the future rather than those that replicate the current economic arrangements” -Shovel ready fund guidelines for applicants (DOC6) | |

| Environmental change | Climate action | “National and Regional benefit – the overriding priorities for grouping projects in the IRG Report being economic stabilisation, stimulation and rebuild in ways that are mapped with the Government’s Economic Plan including the transition to a carbon–neutral New Zealand” Cabinet paper outlining the establishment of the Infrastructure Reference Group, discussion regarding criteria to assess projects (DOC2) |

| Climate resilience | “Our investment decisions as part of the COVID-19 recovery give us a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity to substantially increase our efforts towards building resilience to natural hazards and the impacts of climate change” Cabinet paper on improving flood resilience in the COVID-19 recovery (DOC5) |

In reality, despite the diverse array of multi-scalar and temporal hopes raised by the Government, due to the organisational processes outlined next, Central Government was generally in the position of being a receiver of the hopes of others in the form of individual projects. As such Table 1 can be viewed as a means to both provide public reassurance of a more hopeful future, as well as influence the direction and nature of projects that would be submitted.

The political statements also stimulated diverse hopes from the public sphere. Here, the significant investment symbolised a possible turning point, with various dissatisfactions of the present becoming visible, as well as an anticipation of a more interventionist state emerging to offset the fear of lower private sector activity. Through commentary and media, Table 2 traces a diverse array of hopes that emerged in the public sphere from organisations, individuals and potential fund applicants, such as Local Government.

Table 2.

Key public sphere discourses and themes during the ‘taking place’ of hope.

| Key discourses | Themes of hope | Examples of hope in public sphere |

|---|---|---|

| Economic prosperity | Providing jobs | “The budget announcement of infrastructure spend and training is a chance for the construction industry to develop specific, targeted actions for impact. As Māori and Pasifika engineers working in the construction and infrastructure sector, we’re calling on the industry to build equity into its response for Māori and Pasifika workers. It’s a huge opportunity – and a wero – for our government and industry to demonstrate their recent public commitments to the Diversity Accord.” Sector engineers Troy Brockbank, Elle Archer, Sifa Pole and Sina Cotter Tait and Honor Columbus in an opinion piece for The Spinoff (MED8) |

| Reinvigorating the the regions | “Keedwell said job creation was a major focus, as was making sure new projects had long-term benefits… “A significant cash injection would enable fast tracking and provide major benefits to our region's social, economic, environmental, and cultural wellbeing” Horizons Regional Council chairperson Rachel Keadwell (MED3) | |

| Addressing housing affordability | “The housing crisis has been a national stain for a long time, particularly given that we don’t lack for land, merely the will to do the right thing with it. Between a lull in pricing and a moral imperative to let the tens of billions being spent help those who need it most, it seems inevitable that a good chunk of the shovel-ready projects are ultimately new homes.” Opinion piece in The Spinoff by former Auckland City Councillor Mark Thomas (MED4) | |

| Environmental change | Climate action | “Just as society has fundamentally changed to mitigate Covid-19, it must fundamentally change to respond to the climate crisis. It is vital for the future wellbeing of New Zealanders and Aotearoa's environment that we use this opportunity to transition to a clean, green, zero-carbon economy.” Eleanor West from Generation Zero in an opinion piece for Stuff.co.nz (MED1) |

| Green recovery | ““Central government is focused on a 'green stimulus' and is actively looking for infrastructure spending that will help with climate change mitigation. The city and regional councils are aligned with this thinking. ”It would be very possible for Wellington to be a leader in the green recovery, given political will.“” Victoria University of Wellington climate change researcher Professor James Renwick (MED7) |

Returning to the two key discourses across both Central Government and the public sphere, a powerful theme of economic prosperity became attached to the shovel ready fund, which could be viewed as a dissatisfaction with the present distribution of resources or opportunities and the core positioning of infrastructure as a promissory note able to both stabilize and transform. This hope was strongly articulated through government framing that the fund could ‘protect jobs’ in the short-term as well as re-orient the economy over the longer-term. Sub-themes included the hope that the shovel ready fund would address, in part, the on-going housing crisis, provide jobs, and reinvigorate the regions. It is noteworthy that the public sphere showed less focus on economic modernisation and productivity than the government, with transformation being viewed through a stronger environmental lens and the ‘green recovery’ framing.

In contrast, the government frequently expressed ambition for long-term economic transformation through official documents which note their aim to build a “productive, sustainable and inclusive economy” (DOC4). In the public sphere, this discourse of opportunity for economic prosperity was also more targeted to the hope that building infrastructure as part of the recovery would address worsening issues around housing affordability. For instance, the Kiwi-Buy coalition (a group of housing organisations including the Salvation Army, Habitat for Humanity, Community Housing Aotearoa and the Housing Foundation) called for:

“a multi-billion dollar spend to echo the substantial build that followed the Great Depression” saying that “this is a unique opportunity to stimulate the economy, support the construction industry, and transform the lives of those living in temporary or substandard housing” (MED6).

This sentence also highlights how hope can be positioned as a space–time relation. The temporal and scalar blurring combines hopes for a future wider transformation at a societal scale with hopes for ‘on the ground’ immediate change that would shift the material reality of communities experiencing inequality and housing affordability.

The second key discourse of environmental progress was similarly articulated across both spheres, but with slight differences. Common sub-themes included hopes for climate action such as a transition to a low carbon economy, but there was divergence with the government focusing more on projects to build ‘climate resilience’ to manage fears of climate disruption while the public expressed a stronger desire to see an alternative future via a ‘green recovery.’ This may be partly explained by how ambitions for climate action and a transition to a low carbon economy have been woven through official discourses surrounding the fund, even though climate change was not a central criteria in decision making. For example, Prime Minister Ardern spoke to the Labour Party Congress in 2020 on the theme of ‘preparing for the future’ as part of the government recovery plan, commenting “Restoring our environment is one thing, decarbonising it is another” (PPR4). A focus on climate change impacts was also reflected in a decision to ring-fence $200 m of the $3bn for projects that would build “resilience to natural hazards and the impacts of climate change” (DOC5).

In the public sphere, even stronger ambitions for environmental progress were articulated by Non-Governmental Organisations and commentators who hoped the fund would provide investment in infrastructure to enable radical climate action. In April 2020 during the application process, a group of environmental NGOs including Greenpeace, Forest & Bird and WWF-New Zealand wrote to the Prime Minister: “urging a ‘transformative’ economic recovery to tackle climate change, save native species, improve freshwater quality, and restore oceans.” (MED2). The groups recommended focussing on “climate friendly economic projects”, such as “electrifying and expanding the rail network, making homes warmer and more energy efficient, investing in renewable energy, and expanding cycleways and active transport” (MED2). Again, this discourse highlighted the space–time aspects of hope, in particular the intersection between wider hopes for future transformation and the local and regional scales and modes through which this could be achieved in the present. This was perhaps one of the strongest hopes articulated in the public sphere. It had synergies with the message of ‘build back better’ and stimulated new advocacy coalitions calling for action on environmental issues, particularly climate change. The political space opened by the shovel ready fund process also allowed for hopes to be directed at issues that were perceived to have not had enough government funding or attention, such as climate change and freshwater quality. The hopes that arose in these spaces then do not just represent what is wished for in the future, but also the disappointments of the past and present.

Overall, the shovel ready fund rapidly became the locus of an array of multi-scalar and multi-temporal hopes, both from the government and the public sphere, in part stimulated by the potentiality of the fund and the slippery, encompassing discourse of Build Back Better. The multiplicity of these hopes demonstrated the important role of events like these in cleaving open spaces of possibility and also, as the next section will show, how the potential for change or transformation would be strongly mediated through its political organisation.

4.2. Organising and Deciding on Hope

The previous section emphasised how the state plays a central role in the framing and scope of hopeful visions, we now draw upon press releases, media, Official Information requests, and Cabinet documents to piece together the less visible and transparent means that determined which hopes would be realised, by whom, how, and why.

Cabinet documents position the Government’s wider response to COVID-19 as involving three key operational phases: 1) fighting the virus and cushioning impact; 2) positioning the economy for recovery; and, 3) resetting and rebuilding (DOC1). Inherent in this messaging is the hope that recovery will provide emergent possibilities rather than a ‘bounce back’ to normality. However, the need for urgency and the first signs of the hidden power of the institutional organisation of hope were becoming visible. The new emergency governance mechanism designed to organise hope by receiving shovel ready fund applications is noteworthy. Crown Infrastructure Partners, a Crown owned company, was directed to quickly establish a new ‘Infrastructure Industry Reference Group’ (IRG), who would receive and assess applications, and advance projects to Ministers who would make the final decision. The IRG would be headed by Crown Infrastructure Partners chair and include ‘industry leaders’ with experience in major organisations, such as the Te Waka Kotahi - the New Zealand Transport Agency, Kiwirail, and the Provincial Growth Fund (PRR1).

Their timeline for the design, establishment, and delivery of the shovel ready fund process was ambitious. Minister for Infrastructure Shane Jones stated: “In just a few short weeks, the IRG, through Crown Infrastructure Partners, has been able to collate the largest ever infrastructure and construction stocktake the nation has ever seen” (PPR3). Applications for the shovel ready fund were open for only two weeks during the strict ‘lockdown’ that prohibited movement beyond homes except for narrowly defined essential services and local recreation in isolation from other households. The message was clear: all parties were going to be under significant time pressure.

Once applications were submitted, the IRG were given the task of organising hope; assessing, filtering, and judging which projects were in accordance with criteria. The call resulted in 1924 applications from across 40 sectors representing $136 billion in value (PPR3); hopes that greatly exceeded the indicative $3 billion budget. The IRG would narrow down these applications via the initial guidance which outlined bids would be judged on construction readiness, regional or public benefit, size and material employment benefits and the overall benefits and risks of the project (DOC6). Guidelines also note consideration would be given to the alignment of projects with the Treasury Living Standards Framework and the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the contribution of ‘economic, social and/or environmental’ value (DOC6). This reflected the government's hopes that this scale of investment could improve structural issues relating to the economy, society, and environment, as well as provide rapid job creation.

However, concern was growing from within and outside Government about the power of the organisation of hope via the selected decision-making criteria. For example, a Treasury report highlighted possible constraints on transformation stating: “we consider that proposals that fit with these longer-term objectives are likely to be underrepresented in the IRG process given its focus on shovel readiness and jobs” (DOC4). A member of the youth climate change organisation Generation Zero wrote about how the emphasis on ‘shovel ready’ may threaten hopes for transformational change, noting these investments were an “intergenerational issue” that must not be subject to “shortsighted decisions that we will regret” (MED1). Similarly, Lawyers for Climate Action wrote to Ministers out of concern for the potential lack of consideration for climate issues within the decision-making process. This group also highlighted the potential of the fund, commenting that the “projects are an opportunity to build resilience to climate change into the economy, and to transition to a low emissions economy faster” (MED5).

The IRG screened applications against the initial criteria and well over half were immediately ruled out. Of the 802 remaining, 48% were submitted by Local Authorities, 17% by Central Government, 10% by private entities, 9% by trusts or charities, 2% by iwi (Māori tribes), 1% by other NGOs, and 13% by other public entities (DOC3). The applications by Central Government agencies to their own fund are of interest as you may expect these to be coordinated with the hopes they outlined in discourse. Yet, while full details of applications are not in the public domain, we can see that no housing projects were submitted by Central Government agencies despite it being a cross-cutting hope. Instead housing projects were submitted largely by Local Government, private applicants, and trusts/charities. Central Government agencies did, however, submit 38 applications for roading projects, despite hopes articulating a desire to decarbonise and modernise the economy, and not “replicate current economic arrangements” (DOC6).

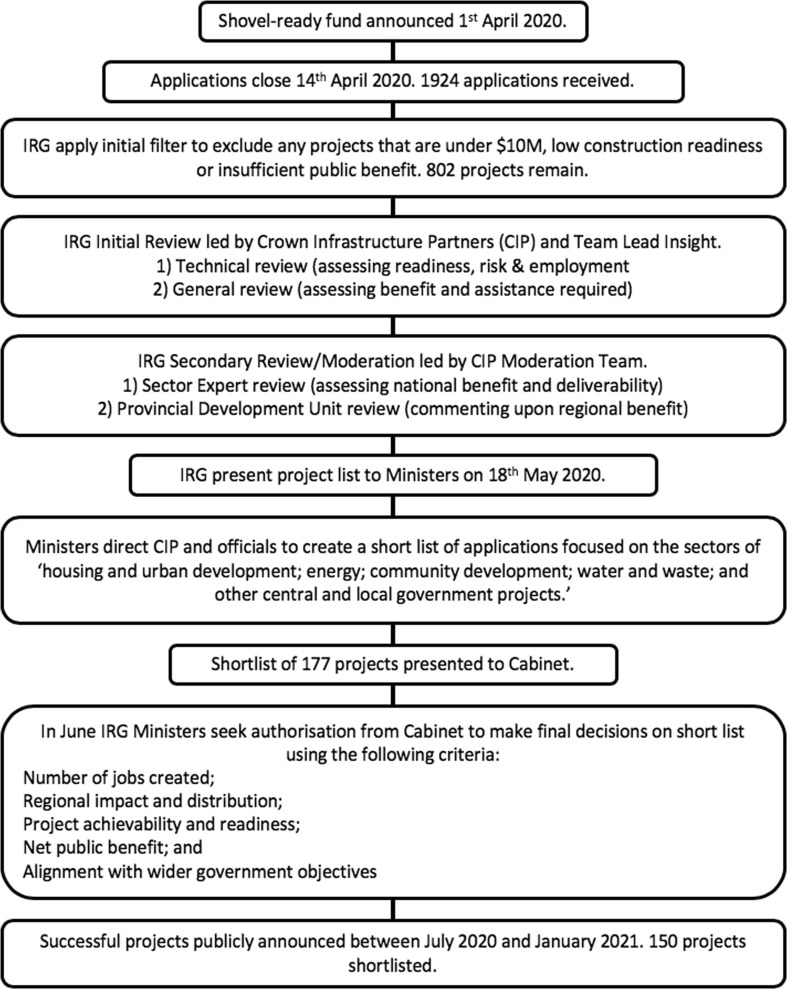

The IRG then conducted several rounds of technical and moderation reviews, but neither made decisions on specific projects nor ranked projects (see Fig. 1 ). A Cabinet paper was at pains to stress the final ‘decision-making’ rested with Cabinet Ministers responsible for the infrastructure fund (the Finance Minister, Infrastructure Minister and Associate Finance Ministers, also referred to as the IRG Ministers): “Importantly, the IRG Report is not deciding on specific projects or making any final recommendations.” (DOC2 - emphasis added). Yet, while the IRG is clearly positioned in Government documents as not having the mandate of a decision-making body, the group had undeniable organisational power in advancing some hopes over others. For example, the IRG presented the narrowed down list of 802 projects to Cabinet in mid-May along with a list of further considerations including regional versus metropolitan employment impacts, impact on iwi, the post COVID-19 economy, sustainability and the environment, and the ability of entities to deliver projects. Following this, Crown Infrastructure Partners and officials were directed by Ministers to produce a further shortlist from the 802 projects: “with a focus on the following sectors: housing and urban development; energy; community development; water and waste; and other central and local government projects” (DOC3). This new technical process reduced the number of bids, and the scope of possible hopes, to 177.

Fig. 1.

An overview of the decision-making process for the shovel-ready fund.

In June, Cabinet documents record that authorisation was sought for the IRG Ministers to make the final decisions on this shorter list using a further list of criteria including, the number of jobs created, regional impact and distribution, project achievability and readiness, net public benefit and alignment with wider government objectives (DOC3). This newly unveiled criteria would have the final input on which hopes would be realised, where and when. While much conforms to the typical logics and language of infrastructure/investment decision-making, the flexible criteria allowing for ‘alignment with wider government objectives’ was presumably intended to provide space for Ministers to address wider hopes. Yet, in reality this had little influence. Of the 177 projects that made it this far, 150 were funded.3 In contrast, the preceding technical processes that, while according to official documents did not have the power of a decision-making body, had a huge influence, reducing 1924 applications to 177.

Project decisions were drip-fed in announcements between July and September 2020. The range of projects was diverse and fragmented, spanning investment in fire stations, digital connectivity, surf clubs, housing projects, a tourism lodge, cycleways, a mushroom farm, swimming pools, roading improvements and a private school (see Table 3 for spending across each official category of funding).

Table 3.

The final ‘shovel ready’ fund allocation (DOC7).

| Category of funding | Amount funded (million $NZ) | Examples of projects funded |

|---|---|---|

| Business | 76.6 | Te Mata Mushrooms, Dawson Falls Lodge Development, Apollo Aviation |

| Community | 543.5 | Kaikōura Aquatic Centre, Youth Hub Christchurch, Taylors Mistake Surf Life Saving Community Infrastructure Rebuild, Kauri Museum, Te Kuiti Sports Stadium, Otorohanga Kiwihouse |

| Environmental | 439.5 | Climate resilience package, Kaipara Stockbank Enhancement, Hector Historic Landfill, Papakawau Estuary Resilience, Minimum Viable Hydrogen Refuelling Network |

| Government | 55.2 | Fire Stations, New Zealand Defence Force Southern Region Maintenance |

| Housing | 469.5 | Unitec Housing Development, Energy Hardship Alleviation Otago, Kainga Ora Tamaki priority Wastewater Upgrades |

| Social | 365.6 | New Whanganui Police Hub, Wellington City Mission Whakamaru, Dementia (Eden Care) Unit, Cancer Society – Christchurch |

| Transport | 684.5 | Christchurch Major Cycleway Routes, Sealing Kaipara Roads, SH94 Homer Tunnel, The Whale Trail Kaikōura, Moonlight Creek Bridge Replacement |

This section emphasises the challenge of organising hope in ways that acknowledge its multi-scalar and temporal nature. While it is relatively straightforward for politicians to launch hopeful events, and adopt slippery terms like ‘Build Back Better’ whose openness stimulates a wide array of hopes, it is much more difficult to design a process that is able to organise the pluralistic, multi-scalar and multi-temporal ways these hopes become expressed. Doing this under conditions of urgency that gives more power to expert rationalities and processes only exacerbates this problem. ‘Following’ the hopes in this way demonstrates not only how the public taking place of hope is subservient to its less visible organisation, but also that many hopes raised struggle to be reconciled with the technical criteria and processes that are given power.

5. Analysing the interface between the taking place and operation of hope

Looking at the various current or impending global crises, hope seems more critical than ever. Research emphasises how hope can open up new political spaces of resistance, create transformative opportunities, foster new networks, or promote more marginalised voices (Head, 2016, Gibson-Graham, 2008, Cameron and Hicks, 2014). As Eagleton (2015: 85) argues “the mere act of being able to imagine an alternative future may distance and relativise the present, loosening its grip on us to the point the future in question becomes more feasible.” More than a prerequisite for reform, hope can also be sustaining in the face of a pandemic that has been described as a ‘triple crisis’, encompassing public health, the economy and, importantly as far as hope is concerned, psychological factors (Žižek, 2020: s7). Scholars draw attention to how hopes provide insights into the struggles of the past and present, the uneven impact of neoliberal policies, or how imagined fears of disruption for some can jostle against hopes for change for others (Kleist and Jansen, 2016, Sparke, 2007, Tsing et al., 2019).

The first point this research demonstrates is how the multiplicity of hopes stimulated by Build Back Better narratives and the ‘shovel ready’ event effortlessly spanned space–time relations. The hopes played an important role in highlighting both global and local concerns as well as past disappointments and future imaginaries. Importantly it also emphasises, however, that these hopes become mediated by current national politics, power, and processes. In common with other countries, the COVID-19 economic recovery strategy in Aotearoa New Zealand created new public articulations of hope and rapidly established technical, expert processes to organise these. Although the broad political positioning of the shovel-ready fund fostered space for a plurality of hopes to flourish, in reality the organisational processes rapidly delineated the scope of the possible. While the government sought to retain formal decision making power for politicians, the technical practices held significant power, whittling 1924 projects down to 177. Before Ministers could make the final decision alongside more subjective or inclusive criteria such as ‘alignment with wider government objectives’, many projects had already been assessed and ruled out.

It was also apparent that, in contrast to how the taking place of hope played out in a public, open arena, the organisation of hope was more opaque. Here politics were less visible, transparent, or democratic, with new processes and criteria created in an ad-hoc manner throughout the rapid assessment process. We also see how the reliance upon typical calculative practices, such as quantification of job numbers, gave significant power to projects—and hopes—that could conform to criteria of this nature. The timescale and urgency associated with the shovel ready fund was also influential, with only two weeks for project formulation and no public consultation regarding the projects submitted, criteria selected, or assessment process created—essentially cleaving the hopes articulated in the public sphere from their organisation. This context helps explain why many successful projects had already been planned, but not yet funded.

This process also limited the temporal dimension of hope. Rather than investing in new hopes represented by new imaginaries, this favoured a process of bringing forward past hopes to the present. This was particularly reflected in the decision-making criteria that required projects to be construction-ready in 6–12 months. While many projects were no doubt worthy, the number of funded initiatives focused on community and health facilities, as well as infrastructure, may be less an example of ‘forward dreaming’ or transformation, and more a result of historic under-funding of Local Government and an ‘infrastructure deficit’ (Bennett, 2020). The multi-scalar nature of hope is therefore related to the multi-scalar nature of disappointment, such as highlighting perceptions of underfunded local and regional priorities.

Such an approach also emphasises how the pluralistic taking place of hope, in all its multi-scale and temporal nature, emerged into a national context and existing policy debates that were much more settled and difficult to disrupt. We can see the intertwining of neoliberal logics with the form of ‘Build Back Better’ framing, not just how hope was seen as deliverable via hard infrastructure investment, but also the typical calculative, expert processes through which they would be organised. This shows synergies with the view of Sparke and Williams (2022: 16) who suggest that while the pandemic “exposed underlying neoliberal transformations…the virus has also exploited and exacerbated all the associated political, economic and social vulnerabilities in co-pathogenic ways.” For example, the pandemic did open space for change, and even stimulated hopes that drew upon dissatisfactions that appeared influenced by existing neoliberal policy settings. Yet, the broad opportunity focused on the scale of state infrastructure investment as stimulus, rather than its nature, and focused on individualised projects rather than coordinated attempts to restructure the present. While the rhetoric promised a future different from the past, it was interwoven with the pre-pandemic political context of Aotearoa, which like other countries has a strong legacy of neoliberal reforms, accompanying disinvestment in government spending, and the resulting inequalities that have been borne from this approach to governing (Kelsey, 1995, Rashbrooke, 2013).

While hope can be positioned as a type of space–time relation with significant disruptive potential, by linking the taking place of hope with its organisation we reveal how this potentiality is bounded both by the technical practices of the processual world, national scale politics, and those expert voices who are given significant tasks and power during times of crisis. We also see how elements of depoliticisation were built into the decision-making process, constraining the potential for radically different futures and acting to reinforce business-as-usual by working at the edges of the status quo (Swyngedouw, 2010, Kenis and Mathijs, 2014). This research, therefore, echoes issues raised by scholars in planning and geography who have emphasized the concerns with processural and techno-managerial politics (Allmendinger and Haughton, 2012, Legacy, 2016, Swyngedouw, 2018). In simple terms, while the taking place of hope demonstrated a broad engagement with an open, indistinct future of the ‘not-yet-become’, its organisation stifled this plurality and privileged a much more familiar ‘what-has-been’. While the broader hope literature emphasises its potential in challenging hierarchical framings, increasing the diversity of imaginaries, or giving voice to grassroots mobilizations (Cameron and Hicks, 2014, Dinerstein and Deneulin, 2012, Gibson-Graham, 2008), in this case, it is clear the associated technical process was ill-suited to organise these.

The shovel ready case study also brings us to reflect on the relationship between hope and disappointment, and in particular how co-pathogenic neoliberal logics and depoliticisation stifled more transformative futures (Sparke and Williams, 2022, Davidson, 2021). As Davidson (2021: 423) describes, disappointment is tied to hope, yet it is not the absence of hope, “one cannot be disappointed without a prior hope.” It emphasises too that each disappointment holds a radical potential, a “sense of ‘accumulated rage,’ or a feeling of unfinished business” (Davidson 2021: 426). Yet, the temporal dynamic of disappointment and hope as expressed in the literature showed significant differences in a study that sought to link the taking place and operation of hope. While the public articulations of hope clearly drew from past disappointments, and a chance to re-litigate failed hopes, the organisation of hope showed no such temporal feedback loop. Although past government disappointments fed into the formation of the hopeful ‘shovel ready’ event, for instance, via a reflection on the failure of previous administrations to take decisive action on climate change, poverty and infrastructure investment, this disappointment-hope feedback loop was absent in the organisation of hope, perhaps as disappointment is experienced so differently in this context. For instance, success may focus on the delivery of an efficient process, rather than the longer-term futures it might open or foreclose.

As such, there is a lesson here for current and future Governments. If, as Cabinet documents emphasise here, there is a genuine desire for transformation, then to be effective this needs to draw upon previous failed hopes for more radical futures and shift attention beyond designing a hopeful event to focus on its organisation. In particular, the objective, technical exercise that unfolded here, was contoured by existing institutionalised forms of neoliberalism and the associated ideational hegemonies, logics, rationalities, and processes within the infrastructure sector. It also highlights that while multiple temporal aspects and futures were readily visible in hope discourse, the scalar dimension was dominated by the national scale, with local and regional actors, even institutional ones, reduced to submitter status. As such, the centralised processes preferred to organise hope may also need to be re-scaled to better realise the different hopes articulated.

More fundamentally, this research emphasises that if governments are interested in transformation, an open call for shovel ready projects might not provide the best opportunity in comparison to implementing a pre-existing long-term vision of what infrastructure, if any, is needed, where, when, and why. Importantly, this anticipatory strategy would also allow space for a more robust and democratic public engagement able to consider the various modes by which hope is expressed by communities within a process carefully designed to assess that plurality. While raising hopes during a crisis can bring short-term gains, as hopes become disappointment it may sow the seeds for a longer-term mistrust in political parties, an erosion of the optimism necessary for future change, and reinforce arguments that call for the death of hope “on the basis that there is no longer the possibility of alternatives to the world as is exists” (see Chandler, 2019: 696). From this standpoint, our research holds as much resonance for progressive politicians, as well as those who are advocating for change from outside.

6. The disappointment and promise of hope

It is undoubted that the COVID-19 response demanded state economic stimulus, that hope is a vital political resource, that infrastructure was a strong candidate for investment, or that many people worked under significant pressure to deliver this. This analysis sought to acknowledge both the construction and representation of the shovel ready fund as an important space of multiple hopes, as well as reveal the powerful instrumentality and politics that we suspected were operating, mostly unseen, and under conditions of urgency. In doing so, our experience in conducting this research concurs with the view from the introduction that while hope is easy to discern from its presence or absence, analysing the ‘taking place’ and ‘operation’ of hope is much more challenging (Anderson, 2006a). This difficulty stems from both the cross disciplinary agenda, in particular designing an methodology able to capture emotional, political, and institutional dimensions, and how this needed to span both public and hidden information, especially as the crisis response relied upon new technical processes implemented in an ad-hoc way largely away from public scrutiny. Yet the challenge of ‘following hope’ also offers promise in developing approaches and insights more able to unpack how economic or institutional decision making practices influence which hopes are realised, by whom, and why. This positioning also provides a useful lens for those concerned with transformation to go beyond the temptation to critique the rhetoric and politics of hope as empty, or simply be grateful for an economic response to COVID-19, to instead explore a research agenda that is better able to connect its taking place and operation, and help bring politics, power and processes to account.

Literature emphasises how hope and fear can disrupt aspects of politics and society, providing both a resource and opportunity to catalyse action, as well as a fear of a threat to normality. This research similarly situated hope as a time–space relation with both constancy and disruptive potential. More than that, the discourses revealed go beyond shedding light on how different actors and agencies perceive current problems, they also demonstrate how hopeful actors need to also focus on the fit-for-purpose nature of institutions, technical criteria, and expert practices, which we argue may be ill-suited to consider plural ‘forward dreaming’ or open to a wide array of voices or vernacular knowledge. Similarly, questions need to be asked as to whether the tendency for centralised decision making in emergency bidding processes like these, could be usefully re-scaled to better reflect the ways hopes become articulated and engage with establish democratic processes.

More broadly, this paper delineates why this topic is so important to interrogate. In simple terms, hope matters. Not just because forward dreaming can aid coping, or how imaginaries are a prerequisite for social change, but they also tell us about the multiple dissatisfactions of the past and present and how, and why, some hopes from some groups are more likely to be heard and responded to in the wake of all-too-frequent crises.

In this regard, the paper title emphasises the co-existence of hope with disappointment, reminding us that despite its common political use hope is not a simple ‘good’. Further, both hope and disappointment have cascading effects that have yet to play out. For example, how often can narratives of hope be deployed before leading to a wider cynicism that becomes attached to faith in political parties, as well as empty phrases such as Build Back Better? The challenge for governments is to develop plans and processes able to respond to crises in a more anticipatory, but in a similarly progressive way as signalled by their rhetoric. If, as seems the case since the Global Financial Crisis, state infrastructure investment is going to be rapidly deployed under conditions of emergency, then there needs to be greater discussion in advance of the kind of society and economy it is desirable to foster, and the related fit-for-purpose processes. As the gaps between rhetoric and reality, and the selected winners and losers become clearer, it would be understandable if the response to COVID-19 leads to a malaise with politics, which may in itself catalyse wider hopes for change. But, as this research argues, this time the spotlight should focus on the power of the processual world rather than just the promise of the substantive.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Iain White: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Raven Cretney: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken with funding from the Aotearoa New Zealand Government National Science Challenge: Resilience to Nature’s Challenges – Kia manawaroa – Ngā Ākina o Te Ao Tūroa. We would like to thank the editor and three reviewers of this paper for some very insightful critiques and suggestions, whilst absolving them for responsibility for any problems that remain.

Author Statement

Eah author contribution equally to the manuscript.

Footnotes

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Document and media sources used in this paper are indicated using a code that corresponds with document details recorded in Appendix 1.

The total number of projects was later updated to 246 shortlisted projects as a number of applications were split into individual projects for implementation purposes (DOC8).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.07.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adey P., Anderson B., Graham S. Introduction: Governing emergencies: beyond exceptionality. Theory, Cult. Soc. 2015;32(2):3–17. doi: 10.1177/0263276414565719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger P., Haughton G. Post-Political Spatial Planning in England: A crisis of consensus? Trans. Instit. Br. Geograph. 2012;37(1):89–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A, Thrift N. Cities: Reimagining the urban. Polity Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. Becoming and Being Hopeful: Towards a Theory of Affect. Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space. 2006;24(5):733–752. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. “Transcending without transcendence”: Utopianism and an ethos of hope. Antipode. 2006;38(4):691–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00472.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. Governing emergencies: The politics of delay and the logic of response. Trans. Instit. Br. Geograph. 2016;41(1):14–26. doi: 10.1111/tran.12100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B., Fenton J. Editorial Introduction: Spaces of Hope. Space Cult. 2008;11(2):76–80. doi: 10.1177/1206331208316649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B., Holden A. Affective Urbanism and the Event of Hope. Space Cult. 2008;11(2):142–159. doi: 10.1177/1206331208315934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, J., 2020. Coronavirus: Cabinet Approves New Legislation to Fast-Track Resource Consents and Boost Economy as it Emerges from Lockdown. Stuff.co.nz. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/121386639/coronavirus-cabinet-approves-new-legislation-to-fasttrack-resource-consents-and-boost-economy-as-it-emerges-from-lockdown (last accessed 27 April 2021).

- Ardern, J., 2020. New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern Victory Speech Transcript: Wins 2020 New Zealand Election. Rev. Transcriptions. https://www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/new-zealand-pm-jacinda-ardern-victory-speech-transcript-wins-2020-new-zealand-election (last accessed 27 April 2021).

- Ardern J. Opinion: An economics of kindness. Beehive Press Release. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/feature/opinion-economics-kindness (last accessed 27 April 2021) 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Baum H. State University of New York Press; New York: 1997. The Organization of Hope: Communities Planning Themselves. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B., 2020. Infrastructure report: NZ Playing Infrastructure Catch-Up After Decades of Under Investment. The New Zealand Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/infrastructure-report-nz-playing-infrastructure-catch-up-after-decades-of-under-investment/GNYWDTGRTCTESANFZU4WGX7SGA/ (last accessed 23rd April 2021).

- Berlant L., editor. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Black, R., 2020. COVID-19: Accelerating the clean-energy transition. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Forum, July. Accessed: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COVID-19-ACCELERATING-THE-CLEAN-ENERGY-TRANSITION.pdf (last accessed 10th August 2021).

- Bloch E. Blackwell; Oxford: 1986. The Principle of Hope. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, E., 1998. Literary Essays. In A. Joron (Trans.), Can Hope be Disappointed? Stanford University Press: Stanford, California.

- Bodewig, C., Hallegate, S., 2020. Building Back Better After COVID-19: How Social Protection can Help Countries Prepare for the Impacts of Climate Change. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/climatechange/building-back-better-after-covid-19-how-social-protection-can-help-countries-prepare (last accessed 27 April 2021).

- Boin, A., McConnell, A., ’T Hart, P., 2008. Governing After Crisis. In; Boin, A., McConnell, A., ’T Hart, P. (Eds.), Governing after Crisis the Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–32.

- Boston J., Martin J., Pallot J., Walsh P. Oxford University Press; Auckland: 1996. Public Management: The New Zealand Model. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. 1st ed. SAGE Publications; 2021. Thematic analysis: A practical guide to understanding and doing. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J., Hicks J. Performative Research for a Climate Politics of Hope: Rethinking Geographic Scale, “Impact” Scale, and Markets: Performative Research for a Climate Politics of Hope. Antipode. 2014;46(1):53–71. doi: 10.1111/anti.12035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carse A., Kneas D. Unbuilt and Unfinished. Environ. Soc. 2019;10(1):9–28. doi: 10.3167/ares.2019.10010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castree N., editor. The Point is to Change it: Geographies of hope and survival in an age of crisis. Wiley-Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D. The death of hope? Affirmation in the Anthropocene. Globalizations. 2019;16(5):695–706. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2018.1534466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek W., Chmutina K. ‘Building Back Better’ is Neoliberal Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Disasters. 2021;46(3):589–609. doi: 10.1111/disa.12502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutard O., Guy S. STS and the City: Politics and Practices of hope. Sci. Technol. Human Values. 2007;32(6):713–734. [Google Scholar]

- Cretney R. Towards a Critical Geography of Disaster Recovery Politics: Perspectives on crisis and hope. Geography. Compass. 2017;11(1) doi: 10.1111/gec3.1230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. A Dash of Pessimism? Ernst Bloch, Radical Disappointment and the Militant Excavation of Hope. Critical Horizons. 2021;22(4):420–437. doi: 10.1080/14409917.2021.1957364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Der Sarkissian R., Dabaj A., Diab Y., Vuillet M. Evaluating the Implementation of the “Build-Back-Better” Concept for Critical Infrastructure Systems: Lessons from Saint-Martin’s Island Following Hurricane Irma. Sustainability. 2021;13(6):3133. doi: 10.3390/su13063133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinerstein A., Deneulin S. Hope Movements: Naming Mobilization in a Post-Development world. Develop. Change. 2012;43(2):585–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01765.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton T. University of Virginia Press; Charlottesville: 2015. Hope without Optimism. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez G., Ahmed I. “Build back better” approach to disaster recovery: Research trends since 2006. Progr. Disaster Sci. 2019;1:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham J.K. Blackwell Publishers; 1996. The End of Capitalism (as we knew it): A feminist critique of political economy. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham J.K. Diverse economies: performative practices for ‘other worlds'. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008;32(5):613–632. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-McLay, C., 2020. New Zealand Launches Massive Spending Package to Combat Covid-19. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/17/new-zealand-launches-massive-spending-package-to-combat-covid-19 (last accessed 27 April 2021).

- Hage G. Pluto Press Australia; 2003. Against Paranoid Nationalism: Searching for hope in a shrinking society. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2000. Spaces of Hope. [Google Scholar]

- Head L. Taylor and Francis; London: 2016. Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Reconceptualising Human-Nature Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Inch A., Slade J., Crookes L. Exploring Planning as a Technology of Hope. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 2020;1–12 doi: 10.1177/0739456X20928400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff S., editor. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. Routledge; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S., 2017. Virtual, Visible, and Actionable: Data Assemblages and the Sightlines of Justice. Big Data Soc. 4(2). https://doi.org/Virtual, Visible, and Actionable: Data Assemblages and the Sightlines of Justice.

- Kelsey J. Auckland University Press; 1995. The New Zealand Experiment. [Google Scholar]

- Kenis A., Mathijs E. Climate change and post-politics: Repoliticizing the present by imagining the future? Geoforum. 2014;52:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleist N., Jansen S. Introduction: Hope over Time—Crisis, Immobility and Future-Making. History Anthropol. 2016;27(4):373–392. doi: 10.1080/02757206.2016.1207636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Legacy C. Transforming transport planning in the postpolitical era. Urban Stud. 2016;53(14):3108–3124. doi: 10.1177/0042098015602649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold S., Feindt P.H., Winkel G., Keller R. Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. J. Environ. Plann. Policy Manage. 2019;21(5):445–463. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luft R. Beyond Disaster Exceptionalism: Social movement developments in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Am. Quart. 2009;61(3):499–547. [Google Scholar]

- MacAskill K. Public Interest and Participation in Planning and Infrastructure Decisions for Disaster Risk Management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019;39:101200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J. Risk and the Rule of Law. Policy Quarterly. 2020;16(3):11–14. doi: 10.26686/pq.v16i3.6548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan C., Boyle M., Kitchin R. Post-Politics, Crisis, and Ireland’s ‘Ghost Estates’. Political Geogr. 2014;42:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD, 2020. Building Back Better: A Sustainable Resilient Recovery after COVID-19. OECD Policy Brief. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=133_133639-s08q2ridhf&title=Building-back-better-_A-sustainable-resilient-recovery-after-Covid-19 (last accessed 27 April 2021).

- Rashbrooke M. In: Inequality: A New Zealand crisis. Rashbrooke M., editor. Bridget Williams Books; 2013. Why Inequality Matters; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A., Graham-McLay, C., 2020. Jacinda Ardern to Govern New Zealand for a Second Term After Historic Victory. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/17/jacinda-arderns-labour-party-set-for-victory-in-new-zealand-election (last accessed 23rd April 2021).

- Roy, A., 2019. New Zealand ‘Wellbeing’ Budget Promises Billions to Care for Most Vulnerable. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/30/new-zealand-wellbeing-budget-jacinda-ardern-unveils-billions-to-care-for-most-vulnerable (last accessed 23rd April 2021).

- Solnit R. Canongate Books; Edinburgh: 2016. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. [Google Scholar]

- Sparke M. Geopolitical Fears, Geoeconomic Hopes, and the Responsibilities of Geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2007;97(2):338–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sparke M., Williams O.D. Neoliberal disease: COVID-19, co-pathogenesis and global health insecurities. Environ. Plann. A: Econ. Space. 2022;54(1):15–32. doi: 10.1177/0308518X211048905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]