Abstract

Nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer, with a dismal prognosis. NSCLC is a highly vascularized tumor, and chemotherapy is often hampered by the development of angiogenesis. Therefore, suppression of angiogenesis is considered a potential treatment approach. Tannic acid (TA), a natural polyphenol, has been demonstrated to have anticancer properties in a variety of cancers; however, its angiogenic properties have yet to be studied. Hence, in the current study, we investigated the antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effects of TA on NSCLC cells. The (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) (MTS) assay revealed that TA induced a dose- and time-dependent decrease in the proliferation of A549 and H1299 cells. However, TA had no significant toxicity effects on human bronchial epithelial cells. Clonogenicity assay revealed that TA suppressed colony formation ability in NSCLC cells in a dose-dependent manner. The anti-invasiveness and antimigratory potential of TA were confirmed by Matrigel and Boyden chamber studies, respectively. Importantly, TA also decreased the ability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) to form tube-like networks, demonstrating its antiangiogenic properties. Extracellular vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) release was reduced in TA-treated cells compared to that in control cells, as measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Overall, these results demonstrate that TA can induce antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effects against NSCLC.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is the most common and fatal malignancy in men and women in the United States. For the year 2022, the American Cancer Society estimated that about 236,740 new cancer cases and 130,180 deaths will occur due to LC in the United States.1 It accounts for 12.5% of all cancer diagnoses and 21% of total cancer-related mortality. Nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) are two different types of cancer, which differ in their histology, patterns of occurrence, and prognoses.2 NSCLC is the most common LC, accounting for 85 percent of all cases. Despite recent advancements in standard treatment approaches such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, the survival rate remains low.

Angiogenesis, like that of other solid tumors, is considered as a critical phase in the advancement of lung malignancies. Angiogenesis is a process of blood vessel formation in tumor microenvironments and represents one of the hallmarks of cancer growth, proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance.3 These newly formed blood vessel networks are responsible for carrying nutrients and oxygen to the tumor cells, and they undergo rapid development and serve as channels to promote metastasis of cancer cells to distant organs.4,5 The lungs are a highly vascularized organ, and studies have shown that NSCLC development and progression are closely linked to major changes in the blood vessel system; thus, inhibiting angiogenesis is a promising approach for NSCLC treatment.6 Angiogenesis inhibitors such as bevacizumab and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors are used to treat lung cancer. Bevacizumab, a potent vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-humanized monoclonal antibody, blocks/inhibits angiogenesis and neovascularization.7 The VGEF is a critical element in cancer angiogenesis, where an induction in VGEF activation is responsible to boost the new blood vessel formation and enhance the development of fresh vasculature networks to be able to efficiently supply the oxygen and nutrient stock to the constantly growing tumor.8 Notably, the VEGF is also a potent stimulator of proliferation and migration; it induces the expression of the metalloproteinases (MMPs). Numerous studies have reported that the overexpression of the VEGF intensifies the tumor growth and metastasis by expanding the vasculature network.9 Bevacizumab has also been studied in SCLC, with varying results in both confined and prolonged disease. When paired with first-line chemotherapy, bevacizumab increased progression-free survival but not overall survival.10 As a result, finding effective antilung cancer drugs, especially those generated from natural resources, is a viable strategy to increase patient compliance and survival rates.

Tannic acid (TA, C76H52O46) (Figure 1A), a naturally occurring water-soluble polyphenolic extract, has been approved as a safe compound by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which made it a safe excipient/active additive in food, drink, and pharmaceutical formulations.11−13 TA is abundantly available, as it is commonly present in plant leaves (e.g., green tea), fruit skins, vegetables, nuts, red wine, coffee, and wood bark. TA (penta-m-digalloyl glucose) contains a unique hydrolyzable structure of tannin with a glucose moiety core.14 The hydroxyl groups of this glucose are esterified with five digallic acids.15 TA exhibits antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties.16 TA’s broad range of bioactivities makes it a potent and viable pharmaceutical additive molecule for various indications. We anticipate that TA could effectively modulate the tumor biology of NSCLC by altering the angiogenesis processes.

Figure 1.

Tannic acid exhibits NSCLC cell-specific cytotoxicity. (A) Chemical structure of tannic acid. (B) Normal human bronchial epithelium cell line (BEAS-2B) and NSCLC (A549 and H1299) cells were treated with different concentrations of TA (0–40 μM) and incubated for 48 and 72 h. Cell proliferation assay was evaluated after addition of the (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) (MTS) reagent. Data represent means ± SEM, n = 3. A table representing the IC50 of TA in NSCLC cells at 48 and 72 h. (C) Cell (BEAS-2B, A549 and H1299) morphology changes were studied using an inverted microscope.

The chemopreventive and anticancer effects of TA have been shown against various types of cancers such as breast,17,18 ovarian,19 and brain cancers.20 The literature supports that TA is able to suppress cancer progression via inhibiting various oncogenic signaling pathways.21−23 TA-induced apoptotic effects on FAS-overexpressed human breast cancer cells have also been reported.24 TA modulates drug efflux and enhances the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents in human cholangiocarcinoma.25 TA is involved in reversing drug resistance by inhibiting the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway,26 inhibiting ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters,27 and downregulating P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and multidrug resistance (MDR) via downregulation of NF-κB and MAPK/ERK.28 A recent study in our laboratory has confirmed TA-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis and lipid metabolism in prostate cancer cells.29,30 TA has been shown to have a potent tyrosine kinase activity.31 In lung cancer cells, TA inhibits stemness by triggering caspase-dependent mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.32

Tannic acid exhibits a selective CXCL12/CXCR4 antagonist, which suggests its antitumor and antiangiogenic potential.33 To the best of our knowledge, TA’s influence on angiogenesis via modulation of the VEGF secretion from NSCLC remains largely unknown.29 Therefore, understanding the response of NSCLC cells to a water-soluble natural anticancer agent (TA) is a clinically unmet need. In addition, revealing the underlying aspects of TA’s antiangiogenic effects and how it may alter the tumor biology holds great promise for identifying new therapeutic targets for NSCLC in clinical translation. Taken together, in this study, our goal is to elucidate the effect of TA on NSCLC cells. We will investigate NSCLC cells that were incubated with different concentrations of TA. Outcomes were measured by characterizing cell proliferation, invasiveness, apoptosis, VEGF secretion, and angiogenesis in NSCLC cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Reagents, and Cell Culture

All the chemicals, solvents, reagents, and cell culture media were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Nonsmall-cell lung cancer cell lines (A549 and H1299), a human normal bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The H1299, A549, BEAS-2B, and HUVECs were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM), and endothelial cell medium-2 (EGM TM-2). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% (w/v) penicillin–streptomycin. Cell lines were maintained at 37 °C with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in an incubator. Cell lines were regularly monitored for their typical morphology and contamination under a microscope. These cells were trypsinized and seeded for in vitro studies.

2.2. Cell Viability

The CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS reagent, Promega, Mannheim, Germany) was performed to determine the cell viability.29 The assay was carried out in 96-well microplates. Each of the A549, H1299, and BEAS-2B cell lines (5 × 103 cells/well) was seeded in their respective media and left overnight for adhesion. On the following day, cells were treated with different concentrations of TA (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM). After 48 and 72 h of treatment, 20 μL of the MTS solution was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The absorbance of each well was measured using a microplate reader (Cytation 5, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) at 490 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cell viability of treated cells was normalized to absorbance readings in untreated control cells (considered to have 100% viability). The concentration required for 50% cell growth inhibition (IC50) was calculated using GraphPad Prism 6.07 software (Dotmatics, San Diego, CA).

2.3. Colony Formation

The impact of TA on inhibiting the clonogenicity of NSCLC cells was tested by the colony formation assay.29 The A549 and H1299 cells (500 cells/well) were cultured in multi-well plates and were allowed to attach and initiate the colonization for 48 h. Then, the medium was replaced with a fresh one containing a varying concentration of TA (2.5, 5, and 10 μM) alongside one without treatment for the control and incubated further for 2 weeks. At the end of the 14 days, colonies were fixed with cold methanol and stained using 0.05% crystal violet at room temperature. The cell colonies were photographed utilizing a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the number of colonies was counted using publicly available ImageJ software (www.imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

2.4. Cell Migration

The effect of TA on NSCLC cell mobility and migration was evaluated through Boyden’s chamber assay and was utilized .29 In brief, the cells were subjected to starvation by culturing them overnight in serum-free media and plated in the upper chambers of a 96-transwell plate at 5 × 105 cells containing 20 μM TA concentration and one with an equivalent amount of the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the control in the serum-free medium, while lower chamber contains complete medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were allowed to migrate toward the fetal bovine serum (FBS) gradient for 24 h; then, the migrated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min and stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature. The migrated cells were imaged under a microscope (EVOS FL microscopy (AMF4300, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA)).

2.5. Wound Healing

The effect of TA on NSCLC cell’s wound healing ability was assessed using a scratch assay.29 Briefly, A549 and H1299 cells were cultured in 6-well plates overnight at the density of 1 × 106 cells/well. When the degree of fusion reached 80%, to create wounds, a 200 μL sterile pipette tip was applied to create wounds on each well. After rinsing the cells with PBS to wash out the debris, cells were treated with 10 μM TA with an untreated well as a control, and the extent of the treatment effect was monitored till 72 h. The residual of the wounds was closely observed and photographed at 24 h intervals using an EVOS FL imaging system.

2.6. Cell Invasion

To analyze the effect of TA on the invasion potential of NSCLCs (A549 and H1299), BioCoat Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were utilized.21,29 The starved cells, as described above, were distributed on the transwell inserts at a density of 3.5 × 104 and incubated with 20 μM TA and PBS (as control) for 24 h. The cells that invaded to the lower chamber were fixed with cold methanol for 30 min and were stained using crystal violet. Invaded cells on membranes were imaged using EVOS FL microscopy.

2.7. Bioinformatics Analysis

A total of 53 altered protein targets of TA were manually curated from the literature and standardized by authors. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and pathway enrichment analyses were obtained from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) plugin of STRING databases. Cytoscape was used for the construction of the final PPI of TA-regulated proteins, which was notified with the color gradient on the basis of the bottleneck property of protein topology.34,35 The three-dimensional (3D) structures of VEGFA (PDB ID: 5FV1), CBP (PDB ID: 5J0D), and P300 (PDB ID: 6GYR) proteins were retrieved from the RCSB protein databank, whereas the 3D structure of TA (PubChem CID: 16129778) was constructed using Biovia Discovery Studio 20202. The FireDock docking server was applied for the interaction analysis between VEGFA, CBP, P300, and TA.36

2.8. Tube Forming Assay

The in vitro antiangiogenic effect of TA on HUVECs (with a passage number lower than five) was analyzed by evaluating the extent of vascular structure/tubular formation of cells.37 The 96-well plates were filled with 50 μL of Matrigel (Becton, Dickinson and Company) diluted with PBS (1:1) and placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 1 h to be solidified. Then, HUVECs (1 × 104 cells/well) were incubated with a range of TA concentrations (10, 15, 20, and 30 μM) and added to the Matrigel-coated plates. After allowing vascular structure formation for 4 h at 37 °C in an incubator, the vascular-like structures/networks were observed using an EVOS FL imaging system; a quantification of three random regions was assessed using ImageJ software using an angiogenesis analyzer.

2.9. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to test the TA influence on the downregulation of the VEGF protein expression on NSCLC. The A549 and H1299 cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well. On the next day, the cells were treated with TA (5, 10, 20, and 30 μM) for 24, 48, and 72 h. Then, the supernatant media were harvested and stored at −20 °C. A commercially available VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit-DVE00 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used to measure the levels of the VEGF, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were attempted using GraphPad Prism (Version 6.07, GraphPad Software) to analyze the data. The results are described as the means ± SEM of three individual sets of experiments. The difference among the groups was estimated by Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The level of statistical significance was set to *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Tannic Acid Inhibits the Proliferation of NSCLC Cells

First, the cell viability assay was utilized to test a safe concentration range of TA against the normal human bronchial epithelium cell line (BEAS-2B). The tested concentrations from 2.5 to 40 μM appear to be nontoxic to BEAS-2B cells in 48 and 72 h treatments (Figure 1B, blue color line graphs and Figure 1C). At these concentrations, it was observed that there is more than 90% of cell viability. Then, the potential inhibitory effect of TA on the proliferation of two NSCLC (A549 and H1299) cells in this concentration range or vehicle solution control over two different incubation times (48 and 72 h) was characterized. As shown in Figure 1B, TA suppressed the growth of NSCLC cells in a dose-dependent and time-responsive manner. IC50 values were calculated as 23.76 ± 1.17 and 10.69 ± 0.83 μM for the A549 cell line and 21.58 ± 1.12 and 7.136 ± 0.64 μM for the H1299 cell line, at 48 and 72 h, respectively. Both A549 and H1299 cells demonstrated varied degrees of phenotypic alterations, such as the loss of viable cells and blebbing, when treated with TA, while control cells maintained their usual phenotype until the treatment step was completed (Figure 1C).

3.2. Tannic Acid Suppresses the Clonogenic Potential of NSCLC Cells

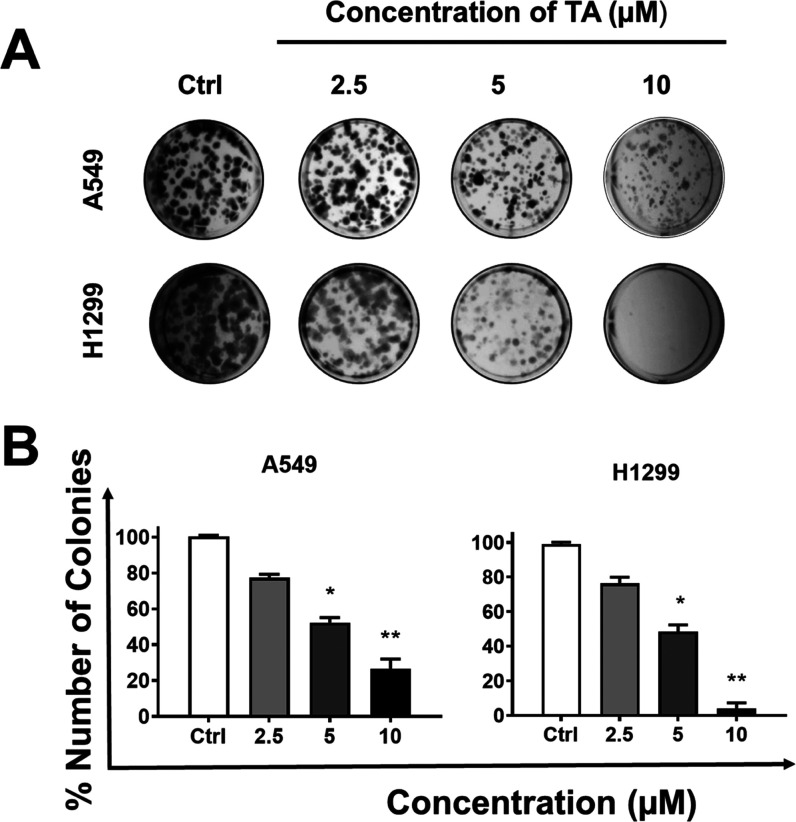

Enhanced clonogenic potential is a very important characteristic of cancer growth and metastasis. The clonogenic growth characteristic is necessary for the cancer cells to establish a primary tumor and eventually metastasis.38 Therefore, the effect of TA on the colony formation ability of A549 and H1299 cells was determined on a long-term basis (14 days) at various concentrations (2.5, 5, and 10 μM) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tannic acid treatment significantly reduces the clonogenic potential of NSCLC cells. The long-term antiproliferative effects of TA were evaluated in a colony formation assay. The colony formation assay was performed on A549 and H1299 cells. The 500 cells were seeded per well of a multi-well plate, and treatment with TA was done at different concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) for 14 days. (A) Colonies were stained with hematoxylin, and images were captured using a phase-contrast microscope. Representative images of the colony formation assay of A549 and H1299. (B) Number of colonies are counted and plotted for A549 and H1299. Data represent means ± SEM, n = 3. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001.

TA exhibited reduction of the number of visible and bigger colonies in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). The quantitative analysis revealed that the percent number of cell colonies was significantly reduced with increasing TA concentration. This effect is similar in both A549 and H1299 cell lines (Figure 2B). Together, these results indicate that TA suppresses the colony formation ability of the NSCLC.

3.3. Tannic Acid Inhibits the Migration and Invasion Potential of NSCLC Cells

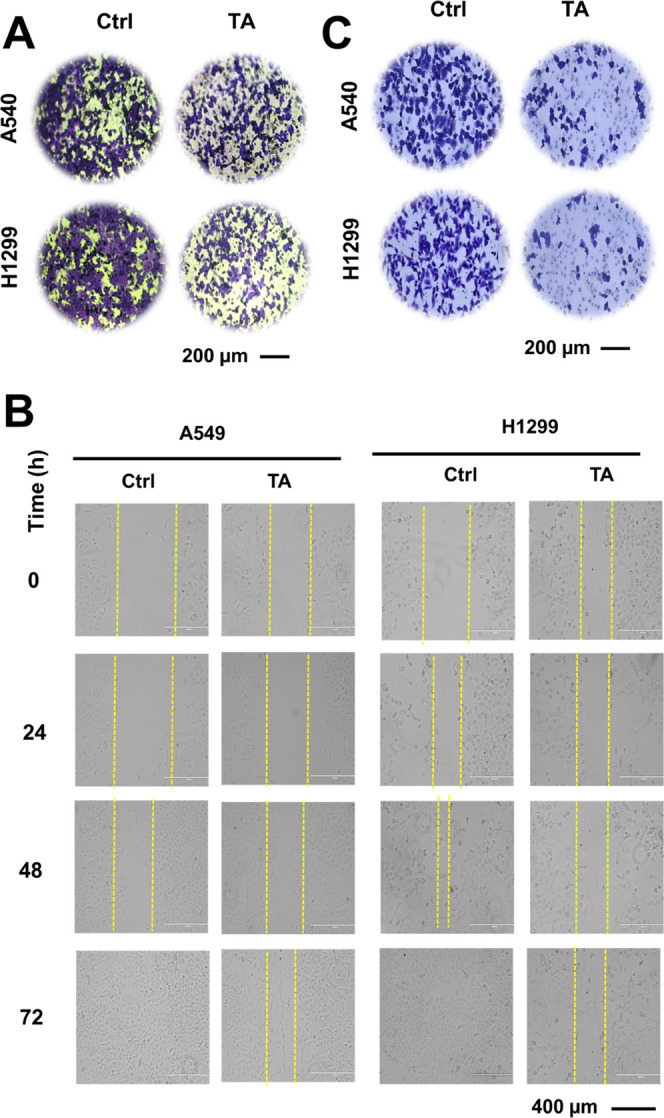

Tumor cell metastasis is known as a complex of events, which involves cell adhesion, extracellular matrix (ECM) component degradation, and tumor cell migration. Thus, blocking one or more of these steps is required for antimetastatic therapy.39 The effects of TA on NSCLC’s invasion and migratory abilities were subsequently assessed by performing the Boyden chamber assay (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Tannic acid treatment minimizes the migration and invasion ability of NSCLC cells. (A) Boyden chamber migration assay was performed on NSCLC cells A549 and H1299. The cells were treated with 0 and 20 μM concentrations for 18 h. After that, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with crystal violet, and left for drying. Furthermore, the images were captured. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) For wound healing assay, cells were wounded by scratching and monitored over different time intervals (24, 48, and 72 h) upon treatment with 10 μM TA to observe the wound closure (40×) magnification, scale bar: 400 μm. (C) Matrigel invasion assay was performed on NSCLC cells A549 and H1299. The cells were treated with TA at 20 μM for 24 h. Thereafter, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained using crystal violet. Upon drying, images were taken. Scale bar: 200 μm.

The number of migrating cells after TA treatment was evidently inhibited in A549 and H1299 cells compared with that in the control (Figure 3A). The ability of the cells to heal the wound and fill the gap to support the reduced migratory capability (Figure 3B) was confirmed by a wound healing assay. The extent of the wound closure was maintained with TA treatment, while the untreated-well wound was healed due to the inherent migratory characteristics of NSCLC. Overall, these results confirm the antimigratory ability of TA on NSCLC cells. In carcinogenic events, cancer cells disseminated through blood or lymphatics to other sites via invasion.40,41 To gain a better understanding of the anti-invasion ability of TA, a transwell assay was performed on A549 and H1299 cells. The number of invaded cells A549 and H1299 toward the FBS gradient was markedly lower in the treatment group compared to that in the control group (Figure 3C). These results indicated that TA could be a promising adjuvant to inhibit the invasion of NSCLC cells.

3.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

After pathway enrichment and PPI analysis of the altered TA target protein dataset (Figure 4), we found the involvement of numerous proteins in different types of cancers. In this enrichment analysis, we found that around 35 proteins out of 53 proteins in the dataset follow a category of cancer-related pathways (hsa05200) with the highest FDR being 2.47E-39. These proteins include MAPK1, NFKBIA, MMP2, TGFB1, NFKB1, CDKN1B, CDK4, PDGFRB, CCNE1, WNT5A, RB1, EGFR, NOTCH1, BRAF, BAX, BCL2L1, CYCS, CASP3, KLK3, GSK3B, CASP9, TCF7, CTNNB1, FAS, STAT1, PTGS2, CASP7, MMP9, JAK2, CXCL12, BCL2, CDKN1A, CXCR4, WNT8A, and VEGFA. After carrying out network analysis, it was found that around five top proteins have bottleneck features of more than two. In between all these important proteins, CTNNB1 and VGFRA were featured as the most important key regulatory proteins of this TA-governed interactome. Among these two proteins, lung cancer was clinically treated using angiogenesis inhibitors which regulate VEGFA. Therefore, the TA influence on this protein is considered in this investigation. VEGFA is also spotted as an important key regulatory node of the TA-governed interactome with a 78 score of degree and 0.33796 (its less than 0.5) score of clustering coefficient. These statistical connections show the importance of VEGFA in the TA-governed interactome. The degree stands for the number of physical or functional interactions of a node with other nodes, and the clustering coefficient represents the closeness of nodes and neighbors; the clustering coefficient also illustrates that the network has a high number of nodes but holds a lesser number of connections, so there are high chances of binding of ligands such as tannic acid.34

Figure 4.

Tannic acid interactive network analyses. Protein–protein interaction: an interactive protein–protein network of all 53 tannic acid-regulated proteins. Color coding was done on the basis of the bottleneck rank of individual protein networks generated from Cytoscape. Most of the proteins are found in various types of cancer groups. CTNNB1 and VEGFA are the top two identified main regulatory proteins in this interactome.

After getting the probable target (VEGFA) of TA, docking analysis was performed; the resultant TA docked perfectly with VEGFA with −36.17 global binding energy (Figure 5A). On the other hand, TA was also able to dock with CBP (Figure 5B) and P300 (Figure 5C) with global binding energies of −34.24 and −59.99, respectively.

Figure 5.

Molecular interaction of tannic acid and angiogenesis-related proteins. Figures were generated using Discovery Studio. (A) Interaction between VEGFA (PDB ID: 5FV1) and tannic acid (PubChem CID: 16129778). Binding pattern of VEGFA and tannic acid docking done using FireDock with −36.17 global binding energy. The amino acid residues of the binding pocket are THR 31, LEU 32, ASP 34, PHE 36, PRO 40, ARG 56, CYS 57, GLY 59, CYS 60, CYS 61, LEU 66, GLU 67, CYS 68, VAL 69, PRO 70, GLU 73, LEU 97, and HIS 99. (B) Molecular interaction between CBP (PDB ID: 5J0D) and tannic acid (PubChem CID: 16129778). Binding pattern of CBP and tannic acid docking done using FireDock with −34.24 global binding energy. The amino acid residues of the binding pocket are Leu1109, Arg1112, Gln1113, Pro1114, Val1115, Asp1116, Leu1120, Gly1121, Ile1122, Tyr1167, Asn1168, Arg1169, Ser1172, Arg1173, and Val1174. (C) Molecular interaction between P300 (PDB ID: 6GYR) and tannic acid (PubChem CID: 16129778). Binding pattern of CBP and tannic acid docking done using FireDock with −59.99 global binding energy. The amino acid residues of the binding pocket are Tyr1394, Ile1395, Ser1396, Tyr1397, Ile1435, Trp1436, Ala1437, Cys1438, Pro1439, Pro1440, Ser1441, Glu1442, Asp1444, Tyr1446, Pro1460, Glu1505, Gly1506, Asp1507, Phe1508, Asn1511, Lys1590, His1591, Val1594, and Arg1627.

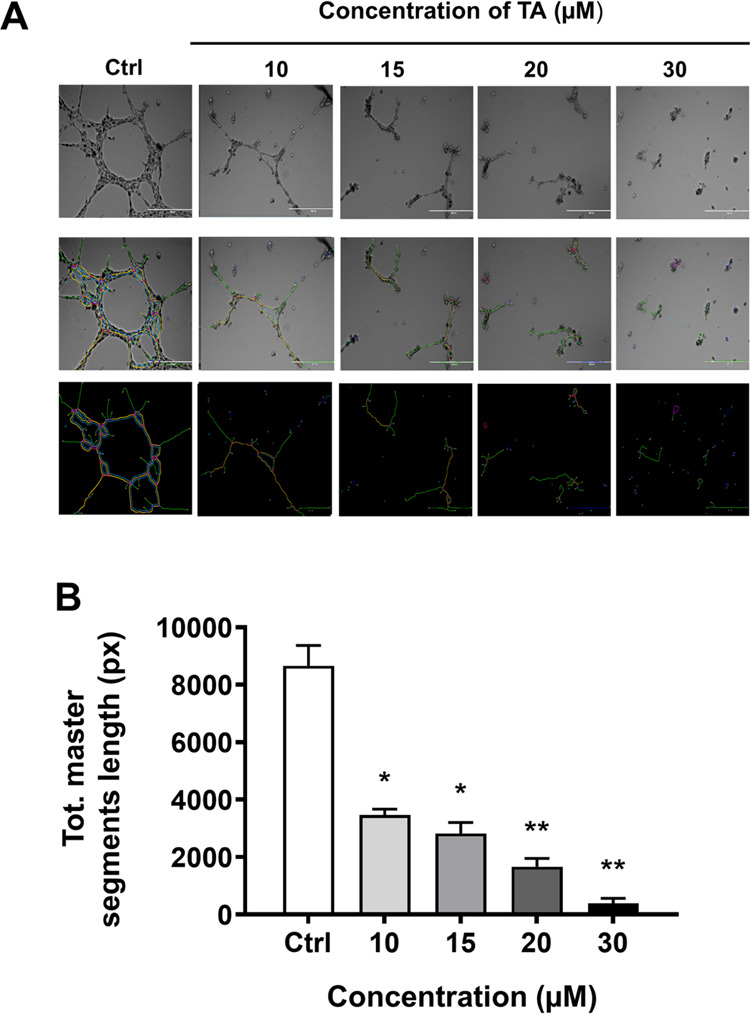

3.5. TA Inhibits In Vitro Tube Formation Activity

Endothelial cell migration, invasion, adhesiveness, tube assembly, and remodeling are footsteps of the new vessel formation (angiogenesis).42 Angiogenesis is a highly regulated process that involves the growth of new blood vessels from the existing vasculature. This process plays an important role in both normal developmental processes and numerous pathologies, ranging from wound healing, tumor growth, and metastasis to inflammation and ocular diseases. Therefore, to determine the physiological significance of the changes in the presence and absence of TA treatment, in vitro angiogenesis was performed on the HUVECs (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tannic acid treatments inhibit the tube formation abilities of HUVECs. In vitro tube formation assay was performed to determine the effect of TA on HUVEC cells. (A) 1 × 104 cells/well were seeded in Matrigel-coated 96-well plates followed by various TA concentrations (10, 15, 20, and 30 μM). Morphology images of vascular-like structures/networks were captured using an EVOS FL imaging system, and a quantification of three random regions was assessed using ImageJ software using an angiogenesis analyzer. (B) Bar graph representing the quantification of three random regions assessed using ImageJ software using an angiogenesis analyzer. Data represent means ± SEM, n = 3. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001.

HUVEC tubular formation was suppressed by incubation with the media conditioned with 10, 15, and 20 μM TA (Figure 6A). The total length of tubules decreased with respect to the increased concentrations of TA: 40.01 ± 2.37, 32.53 ± 4.50, and 19.22 ± 3.37% (Figure 6B). The control group was HUVECs incubated with untreated media and was set as 100%, proposing that the TA treatment with 20 μM was able to inhibit tube formation in HUVECs.

3.6. TA Significantly Reduces VEGF Secretion by NSCLC Cells

Angiogenesis occurs primarily due to the production of excessive VEGF.5,43 Therefore, we sought to investigate whether TA inhibits the secretion of VEGF using ELISA (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Tannic acid treatment significantly lowers the VEGF secretion from tumor cells. ELISA assay was performed to determine the effect of TA on the VEGF protein expression in (A) A549 and H1299 (B) cells. The cells were treated with TA (5, 10, 20, and 30 μM) for 24, 48, and 72 h. The supernatant media were used to measure the levels of VEGF secretion. Data represent means ± SEM, n = 3. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001.

The treatment of NSCLC cells with different concentrations of TA significantly decreased the VEGF expression level in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that TA treatment has an inhibitory effect on the level of the VEGF produced. Indeed, as the treatment continued with longer incubation, the level of the VEGF also decreased accordingly in both cell lines. The reduction in VEGF levels was statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers globally, both in terms of incidence and mortality (18 percent of total cancer deaths).44 NSCLC is the most common form of LC, accounting for 85 percent of all occurrences. Despite enormous scientific investigations in lung cancer, the incidence and fatality rates have not decreased significantly.45 The presence of increased angiogenesis in NSCLC has been linked to a bad prognosis.46,47 Several angiogenic switch molecular mediators are linked to a poor clinical outcome.48 Hence, antiangiogenesis therapy remains an attractive treatment option for patients with NSCLC.49 In this study, we investigated a simple yet clinically suitable natural molecule-based treatment approach for NSCLC, which may augment the survival outcome by inhibiting angiogenesis and decreasing the systemic side effect.

TA is a naturally occurring polyphenol molecule. The water-soluble polyphenols in TA attribute unique biological properties, which made it an excellent candidate for the medicinal applications. Accumulating studies confirmed TA as an antimutagenic, antioxidant, and anticancer agent.19,24,50,51 Moreover, TA has been used for therapeutic purposes for centuries.22 Notably, TA has become a very interesting topic in anticancer drug discovery because of its economic and organic production, in comparison to other chemical components. Previous reports have shown anticancer potential in breast, prostate cancer, and other cancers,17,29 but to the best of our knowledge, its effect on NSCLC due to the antiangiogenesis effect and downregulation of the VEGF signaling pathway has not yet been studied.

In our study, TA has shown a significant anticancer effect on NSCLC cells. The quantification of the proliferation of A549 and H1299 by cell viability studies showed that TA treatment reduces the rate of the proliferations of both cell lines drastically and inhibits the growth and suppresses the cell viability of A549 and H1299 (Figure 1). Additionally, our results showed that in the presence of TA, there is a significant decline in the number of colonies (Figure 2). It was noticed that viable cells and colonies of H1299 were not as much as those in A549 cells. This result suggests that H1299 cells are more sensitive to TA treatment than A549 cells. Moreover, there is an inhibitory effect on the number of cells invaded and migrated, on A549 and H1299 (Figure 3). The process of wound healing predominantly regulates and promotes the growth of malignant cells52 and migration of cancer cells; our scratch assay results support that TA has an inhibitory effect on the mechanism that regulates wound healing, in a time-dependent fashion in both cell lines. Our findings are consistent with the previous literature that have reported the antitumoral and anticancer activity of TA on other types of cancers such as prostate cancer,29,53 breast cancer,17,24 and colon cancer.54

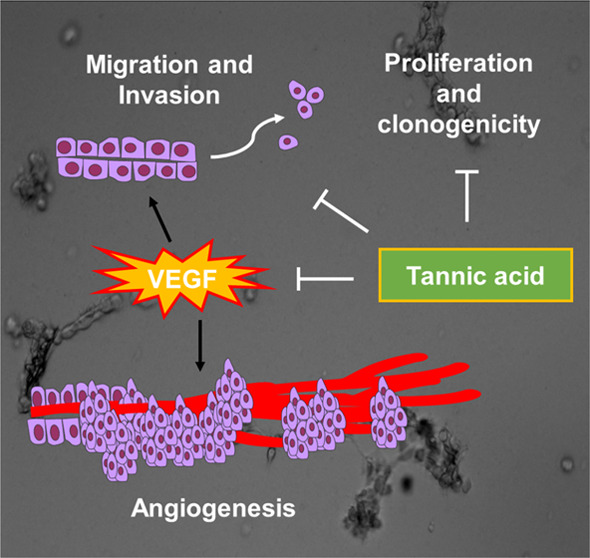

Angiogenesis occurs to build an intact network to circulate nutrition and oxygen and is vital for cancer cells’ function, growth, and survival. A high level of the VEGF is necessary for this network, and if its function is hindered and could not keep up with the rapid growth of the tumor, the cancerous cells have no other option but to undergo apoptosis.6 Collective reports show that a decreased level of the VEGF caused inhibition of tumor growth and proliferation.9,55−57 We have measured the VEGF protein concentrations by ELISA, and the respective data revealed that the VEGF level of the supernatant remarkedly decreased following TA treatment. A high amount of VEGF is generated from cancer cells early in tumor-induced angiogenesis, and it then binds to VEGFR2 on endothelial cells to cause angiogenesis.58−60 Our results (Figures 6 and 7) suggest that such a decrease in VEGF secretion in NSCLC when exposed to TA had attributed to the reduction of tube formulation capability, hence leading to a decline in angiogenesis and formation of intact blood vasculature networks. Inhibition of angiogenesis would potentially suppress the metastasis and inhibit the chance of tumor cells spreading around the patient’s body.

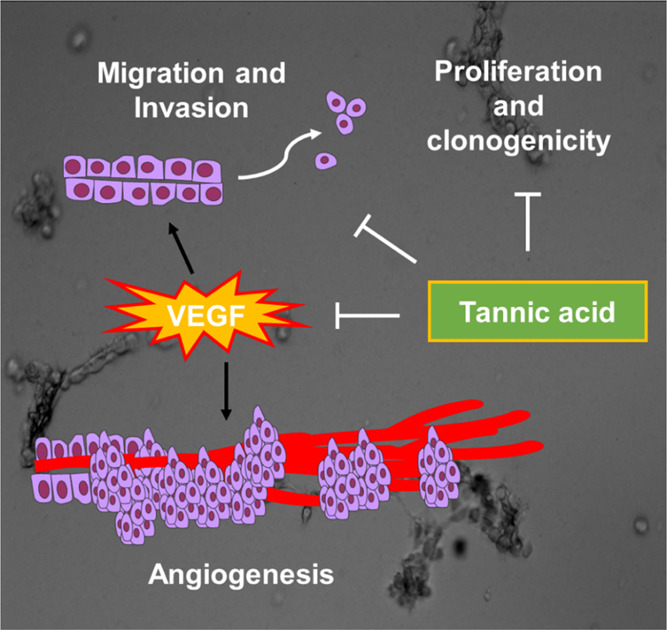

Overall, TA has an advantageous therapeutic profile owing to its safe and nontoxic plant-based nature, which makes it a very suitable candidate for cancer therapy, especially for unfit NSCLC patients. These results manifest that TA acts as a potent inhibitor for blood vessel formation, hence strengthening the rationale of using TA as an antiangiogenic agent for NSCLC therapy (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation depicting the mechanism of action of TA in NSCLC.

It is noteworthy to mention that additional in-depth studies and in vivo studies would add more insights to the potential use of TA as a new adjuvant treatment modality or a potential preventive agent for NSCLC.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that TA inhibits angiogenesis via decreasing the VEGF level and also suppressing the growth of the NSCLC cells. TA treatment showed antitumor effects through various functional assays in NSCLC cells. Furthermore, the TA treatment strategy enhanced the antimetastatic activity such as reduction in the cell migratory effect and invasion, in addition to significant inhibition of the wound healing process. We believe that these findings will pave the way for the transfer of TA as a novel natural therapeutic for NSCLC therapy, either alone or in combination with other anticancer drugs, to improve the patient’s quality of life by reducing cancer therapy side effects. The data also provide support for that TA can be used as a preventive agent against NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the start-up research support from the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis and Department of Immunology and Microbiology, School of Medicine, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, given to M.J., M.M.Y., and S.C.C. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute’s funding, SC1GM139727, R01 CA210192, and R01 CA206069.

Author Contributions

E.H., P.K.B.N., and A.D.: conceptualization, software, methodology, resources, and writing—original draft, review, and editing. M.S., S.C.C., and M.J.: software, resources, and writing—review and editing. M.M.Y.: conceptualization, software, methodology, resources, writing—original draft, review, and editing, and supervision.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Fuchs H. E.; Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dela Cruz C. S.; Tanoue L. T.; Matthay R. A. Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin. Chest Med. 2011, 32, 605–44. 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P.; Jain R. K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N.; Gerber H. P.; LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–76. 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaruz L. C.; Socinski M. A. The role of anti-angiogenesis in non-small-cell lung cancer: an update. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 17, 26 10.1007/s11912-015-0448-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta L. G.; Chen H.; O’Connor S. J.; Chisholm V.; Meng Y. G.; Krummen L.; Winkler M.; Ferrara N. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 4593–4599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Dabrosin C.; Yin X.; Fuster M. M.; Arreola A.; Rathmell W. K.; Generali D.; Nagaraju G. P.; El-Rayes B.; Ribatti D.; Chen Y. C.; Honoki K.; Fujii H.; Georgakilas A. G.; Nowsheen S.; Amedei A.; Niccolai E.; Amin A.; Ashraf S. S.; Helferich B.; Yang X.; Guha G.; Bhakta D.; Ciriolo M. R.; Aquilano K.; Chen S.; Halicka D.; Mohammed S. I.; Azmi A. S.; Bilsland A.; Keith W. N.; Jensen L. D. Broad targeting of angiogenesis for cancer prevention and therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S224–S243. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Regulation of angiogenesis: a new function of heparin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34, 905–909. 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90588-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanino A.; Manzo A.; Carillio G.; Palumbo G.; Esposito G.; Sforza V.; Costanzo R.; Sandomenico C.; Botti G.; Piccirillo M. C.; Cascetta P.; Pascarella G.; La Manna C.; Normanno N.; Morabito A. Angiogenesis Inhibitors in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 655316 10.3389/fonc.2021.655316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami E.; Mu Y.; Shields D. N.; Chauhan S. C.; Kumar S.; Cory T. J.; Yallapu M. M. Mannose-decorated hybrid nanoparticles for enhanced macrophage targeting. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019, 17, 197–207. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami E.; Bhusetty Nagesh P. K.; Chowdhury P.; Elliot S.; Shields D.; Chand Chauhan S.; Jaggi M.; Yallapu M. M. Development of Zoledronic Acid-Based Nanoassemblies for Bone-Targeted Anticancer Therapy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 2343–2354. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin A.; Isoda F.; Patel H.; Yen K.; Nguyen L.; Hajje D.; Schwartz M.; Mobbs C. FDA-approved drugs that protect mammalian neurons from glucose toxicity slow aging dependent on cbp and protect against proteotoxicity. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27762 10.1371/journal.pone.0027762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski P.; Zmigrodzka M.; Tomaszewska E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda K.; Czupryn M.; Antos-Bielska M.; Szemraj J.; Celichowski G.; Grobelny J.; Krzyzowska M. Tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles for wound healing: the importance of size. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 991–1007. 10.2147/IJN.S154797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzini P.; Arapitsas P.; Goretti M.; Branda E.; Turchetti B.; Pinelli P.; Ieri F.; Romani A. Antimicrobial and antiviral activity of hydrolysable tannins. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1179–1187. 10.2174/138955708786140990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez O.; Capdevila J. Z.; Dalla G.; Melchor G. Efficacy of Rhizophora mangle aqueous bark extract in the healing of open surgical wounds. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 564–568. 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth B. W.; Inskeep B. D.; Shah H.; Park J. P.; Hay E. J.; Burg K. J. Tannic Acid preferentially targets estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2013, 2013, 369609 10.1155/2013/369609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikoo K.; Sane M. S.; Gupta C. Tannic acid ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and potentiates its anti-cancer activity: potential role of tannins in cancer chemotherapy. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 251, 191–200. 10.1016/j.taap.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Zhang T.; Wang B.; Li H.; Li P. Tannic acid, an inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase, sensitizes ovarian carcinoma cells to cisplatin. Anticancer Drugs 2012, 23, 979–990. 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328356359f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bona N. P.; Pedra N. S.; Azambuja J. H.; Soares M. S. P.; Spohr L.; Gelsleichter N. E.; de M. M. B.; Sekine F. G.; Mendonca L. T.; de Oliveira F. H.; Braganhol E.; Spanevello R. M.; da Silveira E. F.; Stefanello F. M. Tannic acid elicits selective antitumoral activity in vitro and inhibits cancer cell growth in a preclinical model of glioblastoma multiforme. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020, 35, 283–293. 10.1007/s11011-019-00519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury P.; Nagesh P. K. B.; Hatami E.; Wagh S.; Dan N.; Tripathi M. K.; Khan S.; Hafeez B. B.; Meibohm B.; Chauhan S. C.; Jaggi M.; Yallapu M. M. Tannic acid-inspired paclitaxel nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer effects in breast cancer cells. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 535, 133–148. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. T.; Wong T. Y.; Wei C. I.; Huang Y. W.; Lin Y. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 421–464. 10.1080/10408699891274273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami E.; Nagesh P. K. B.; Chowdhury P.; Chauhan S. C.; Jaggi M.; Samarasinghe A. E.; Yallapu M. M. Tannic Acid-Lung Fluid Assemblies Promote Interaction and Delivery of Drugs to Lung Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 111 10.3390/pharmaceutics10030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie F.; Liang Y.; Jiang B.; Li X.; Xun H.; He W.; Lau H. T.; Ma X. Apoptotic effect of tannic acid on fatty acid synthase over-expressed human breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 2137–2143. 10.1007/s13277-015-4020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naus P. J.; Henson R.; Bleeker G.; Wehbe H.; Meng F.; Patel T. Tannic acid synergizes the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs in human cholangiocarcinoma by modulating drug efflux pathways. J. Hepatol. 2007, 46, 222–229. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam S.; Smith D. M.; Dou Q. P. Tannic acid potently inhibits tumor cell proteasome activity, increases p27 and Bax expression, and induces G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Epidemiol., Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10, 1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink M.; Ashour M. L.; El-Readi M. Z. Secondary Metabolites from Plants Inhibiting ABC Transporters and Reversing Resistance of Cancer Cells and Microbes to Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 130 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. X.; Sun Y. B.; Wang S. Q.; Duan L.; Huo Q. L.; Ren F.; Li G. F. Grape seed procyanidin reversal of p-glycoprotein associated multi-drug resistance via down-regulation of NF-kappaB and MAPK/ERK mediated YB-1 activity in A2780/T cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71071 10.1371/journal.pone.0071071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagesh P. K. B.; Hatami E.; Chowdhury P.; Kashyap V. K.; Khan S.; Hafeez B. B.; Chauhan S. C.; Jaggi M.; Yallapu M. M. Tannic Acid Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 68 10.3390/cancers10030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagesh P. K. B.; Chowdhury P.; Hatami E.; Jain S.; Dan N.; Kashyap V. K.; Chauhan S. C.; Jaggi M.; Yallapu M. M. Tannic acid inhibits lipid metabolism and induce ROS in prostate cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 980 10.1038/s41598-020-57932-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvin P.; Joung Y. H.; Kang D. Y.; Sp N.; Byun H. J.; Hwang T. S.; Sasidharakurup H.; Lee C. H.; Cho K. H.; Park K. D.; Lee H. K.; Yang Y. M. Tannic acid inhibits EGFR/STAT1/3 and enhances p38/STAT1 signalling axis in breast cancer cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 720–734. 10.1111/jcmm.13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sp N.; Kang D. Y.; Kim D. H.; Yoo J. S.; Jo E. S.; Rugamba A.; Jang K. J.; Yang Y. M. Tannic Acid Inhibits Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Stemness by Inducing G(0)/G(1) Cell Cycle Arrest and Intrinsic Apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 3209–3220. 10.21873/anticanres.14302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Beutler J. A.; McCloud T. G.; Loehfelm A.; Yang L.; Dong H. F.; Chertov O. Y.; Salcedo R.; Oppenheim J. J.; Howard O. M. Tannic acid is an inhibitor of CXCL12 (SDF-1alpha)/CXCR4 with antiangiogenic activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 3115–3123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhasmana A.; Uniyal S.; Anukriti; Kashyap V. K.; Somvanshi P.; Gupta M.; Bhardwaj U.; Jaggi M.; Yallapu M. M.; Haque S.; Chauhan S. C. Topological and system-level protein interaction network (PIN) analyses to deduce molecular mechanism of curcumin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12045 10.1038/s41598-020-69011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhasmana A.; Uniyal S.; Somvanshi P.; Bhardwaj U.; Gupta M.; Haque S.; Lohani M.; Kumar D.; Ruokolainen J.; Kesari K. K. Investigation of Precise Molecular Mechanistic Action of Tobacco-Associated Carcinogen ′NNK′ Induced Carcinogenesis: A System Biology Approach. Genes 2019, 10, 564 10.3390/genes10080564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza S.; Dhasmana A.; Bhatt M. L. B.; Lohani M.; Arif J. M. Molecular Mechanism of Cancer Susceptibility Associated with Fok1 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism of VDR in Relation to Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 199–206. 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi T.; Yi Z.; Cho S. G.; Luo J.; Pandey M. K.; Aggarwal B. B.; Liu M. Gambogic acid inhibits angiogenesis and prostate tumor growth by suppressing vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 signaling. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1843–1850. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundram V.; Chauhan S. C.; Ebeling M.; Jaggi M. Curcumin attenuates β-catenin signaling in prostate cancer cells through activation of protein kinase D1. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35368 10.1371/journal.pone.0035368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. A.; Lomax-Browne H. J.; Carter T. M.; Kinch C. E.; Hall D. M. Molecular interactions in cancer cell metastasis. Acta Histochem. 2010, 112, 3–25. 10.1016/j.acthis.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K.; Weinberg R. A. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 265–273. 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S.; Wang P.; Toh A.; Thompson E. W. New Insights Into the Role of Phenotypic Plasticity and EMT in Driving Cancer Progression. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 71 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; He L.; Wang J.; Wang Q.; Sun C.; Li Y.; Jia K.; Wang J.; Xu T.; Ming R.; Wang Q.; Lin N. Anti-angiogenic effect of Shikonin in rheumatoid arthritis by downregulating PI3K/AKT and MAPKs signaling pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 113039 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Cong Q.; Du Z.; Liao W.; Zhang L.; Yao Y.; Ding K. Sulfated fucoidan FP08S2 inhibits lung cancer cell growth in vivo by disrupting angiogenesis via targeting VEGFR2/VEGF and blocking VEGFR2/Erk/VEGF signaling. Cancer Lett. 2016, 382, 44–52. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H.; Ferlay J.; Siegel R. L.; Laversanne M.; Soerjomataram I.; Jemal A.; Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F.; Ferlay J.; Soerjomataram I.; Siegel R. L.; Torre L. A.; Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst R. S.; Onn A.; Sandler A. Angiogenesis and lung cancer: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3243–3256. 10.1200/JCO.2005.18.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini G.; Vignati S.; Basolo F.; Bevilacqua G.; Lucchi M.; Mussi A.; Angeletti C. A.; Ciardiello F.; De Laurentiis M.; De Placido S. Angiogenesis as a Prognostic Indicator of Survival in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma: a Prospective Study. JNCI, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 881–886. 10.1093/jnci/89.12.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar J.; Goss G. D. Tumor vasculature as a therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 609–620. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182435f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. D.; Le T. M.; Haggstrom D. E.; Gentzler R. D. Angiogenesis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2015, 4, 515–523. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perumal P. O.; Mhlanga P.; Somboro A. M.; Amoako D. G.; Khumalo H. M.; Khan R. M. Cytoproliferative and Anti-Oxidant Effects Induced by Tannic Acid in Human Embryonic Kidney (Hek-293) Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 767 10.3390/biom9120767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahal A.; Kumar A.; Singh V.; Yadav B.; Tiwari R.; Chakraborty S.; Dhama K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: the interplay. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264 10.1155/2014/761264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K. M.; Opdenaker L. M.; Flynn D.; Sims-Mourtada J. Wound healing and cancer stem cells: inflammation as a driver of treatment resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Growth Metastasis 2015, 8, CGM-S11286 10.4137/CGM.S11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt S.; Adali O. Tannic Acid Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, Invasion of Prostate Cancer and Modulates Drug Metabolizing and Antioxidant Enzymes. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 781–789. 10.2174/1871520616666151111115809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Ding G. B.; Liu W.; Fu R.; Sajid A.; Li Z. Tannic acid directly targets pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 to attenuate colon cancer cell proliferation. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5547–5559. 10.1039/C8FO01161C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuazo-Gaztelu I.; Casanovas O. Unraveling the Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Ecosystems. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 248 10.3389/fonc.2018.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal K.; Ebos J.; Rini B. Angiogenesis and the tumor microenvironment: vascular endothelial growth factor and beyond. Semin. Oncol. 2014, 41, 235–251. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Zhang K.; Nam S.; Anderson R. A.; Jove R.; Wen W. Novel angiogenesis inhibitory activity in cinnamon extract blocks VEGFR2 kinase and downstream signaling. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 481–488. 10.1093/carcin/bgp292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plate K. H.; Breier G.; Risau W. Molecular mechanisms of developmental and tumor angiogenesis. Brain Pathol. 1994, 4, 207–218. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K.; Roberts O. L.; Thomas A. M.; Cross M. J. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cell. Signalling 2007, 19, 2003–2112. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau N.; Myers C. Breast cancer-induced angiogenesis: multiple mechanisms and the role of the microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2003, 5, 140 10.1186/bcr589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]