Abstract

The whole world is still challenged with COVID-19 pandemic caused by Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) which has affected millions of individuals around the globe. Although there are prophylactic vaccines being used, till now, there is ongoing research into discovery of drug candidates for total eradication of all types of coronaviruses. In this context, this study sought to investigate the inhibitory effects of six selected tropical plants against four pathogenic proteins of Coronavirus-2. The medicinal plants used in this study were selected based on their traditional applications in herbal medicine to treat COVID-19 and related symptoms. The biological activities (antioxidant, free radical scavenging, and anti-inflammatory activities) of the extracts of the plants were assessed using different standard procedures. The phytochemicals present in the extracts were identified using GCMS and further screened via in silico molecular docking. The data from this study demonstrated that the phytochemicals of the selected tropical medicinal plants displayed substantial binding affinity to the binding pockets of the four main pathogenic proteins of Coronavirus-2 indicating them as putative inhibitors of Coronavirus-2 and as potential anti-coronavirus drug candidates. The reaction between these phytocompounds and proteins of Coronavirus-2 could alter the pathophysiology of COVID-19, thus mitigating its pathogenic reactions/activities. In conclusion, phytocompounds of these plants exhibited promising binding efficiency with target proteins of SARS-COV-2. Nevertheless, in vitro and in vivo studies are important to potentiate these findings. Other drug techniques or models are vital to elucidate their compatibility and usage as adjuvants in vaccine development against the highly contagious COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus-2, Medicinal plants, Phytochemicals, In silico molecular docking

Introduction

For several decades, infectious diseases particularly those induced by pathogenic viruses have a significant devastating effect on human wellbeing and health (Oladele et al. 2020a, b, c, d). At present, the whole world is challenged with COVID-19 pandemic caused by Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) which has affected millions of individuals around the globe (Huang et al. 2020; Oladele et al. 2021a, b). The SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus and a member of the Coronaviridae family (Wang et al. 2020). Although there are prophylactic vaccines being used, till now, there is ongoing research into drug candidate for total eradication of all types of coronaviruses and therapy or medication to inhibit the progression of the pathogenesis of the disease. Thus, there is urgent need for the discovery of non-invasive, novel, natural, and non-toxic therapeutic agents that will effectively suppress the pathogenesis of Coronavirus-2.

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to either the alpha or beta human coronaviruses; several processes including pathogenesis, infectivity, virulence, and virus release are mediated by unique structural and accessory proteins (Issa et al 2020; Hassan et al. 2021). Worthy of note are the main protease, primase, ADP ribose phosphatase, replicase protein, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Das et al. 2021; Maio et al. 2021). The activity of the main protease (Mpro), a 33.8 kDa enzyme is highly integral to the release of the viruses’ functional polypeptide via proteolytic processing necessary for its replication and transcription (Zhou et al. 2020), unlike the ADP ribose phosphatase and replicase protein, which are associated with altering the immune response of the host by removal of ADP-ribose from ADP-ribosylated proteins and viral replication (Michalska et al. 2020). Functionally similar to Mpro, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase has been implicated in the replication of virus genome and gene transcription, making these proteins a potential candidate drug targets in mitigating viral lethality (Maio et al. 2021).

Medicinal plants are used since time immemorial in the treatment of various diseases due to their accessibility, inexpensive natural products, and host broad range of both biologically and chemically active phytocompounds which have been used in the synthesis of therapeutic drugs (Oladele et al. 2020a,b, 2021a, b). They also serve as sources of adjuvants for vaccine development. The six medicinal plants (Neem [Azadirachta indica Juss], Jute [Corchorus olitorius], Cassia alata, Phyllanthus amarus, bitter leaf [Vernonia amygdalina], and Cashew [Anacardium occidentale L.]) used in this study have been reported to have antioxidant, antiviral, immunomodulatory, cytoprotective, and antipyretic properties. Mode of actions of SARS-CoV-2 includes immunosuppression, alteration to physiological functions of alveoli, and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways leading to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH), a cytokine profile with a hyperinflammatory syndrome associated with multiorgan failure linked to COVID-19 severity including lung damage (Oladele et al. 2020c).

Based on the aforementioned, this study sought to investigate the cytoprotective effects of six tropical medicinal plants used in traditional medicine to treat COVID-19-related symptoms and examine the inhibitory ability of the active natural products and phytochemicals present in these plants against five essential proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Furthermore, the study explores the in vitro biological properties of the plants aqueous extracts.

Materials and methods

Materials

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), folin ciocalteau, Tris–HCl, ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-1,2-picrylhydrazyl), TPTZ (2,4,6,-tripyridyl-s-triazine), and deoxyribose were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, Mo, USA. Hydrochloric acid (HCl), methanol, gallic acid, sulphuric acid (H2SO4), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), aluminium chloride, potassium acetate, potassium persulphate, sodium nitroprusside, hydrogen peroxide, glacial acetic acid, naphthylethylenediamine dichloride, NADH, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and L-ascorbic acid were all purchased from Merck, USA. All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Extraction of the aqueous extracts of the plants

The six tropical medicinal plants (Azadirachta indica Juss, Corchorus olitorius, Cassia alata, Phyllanthus amarus, Vernonia amygdalina, and Anacardium occidentale L.) used in this study are currently used in traditional and herbal medicine to treat and/or prevent COVID-19-related symptoms (Oladele et al. 2020a, b, c, d). Fresh leaves of Azadirachta indica, Corchorus olitorius, Cassia alata, Phyllanthus amarus, Vernonia amygdalina, and bark of Anacardium occidentale were air dried at room temperature in the Biochemistry laboratory of the Department of Chemical Sciences, Faculty of Science, Kings University, Odeomu, Osun State. The dried leaves were pulverized using electric blender. The powdered sample was weighed and soaked in 6 volumes of distilled water for 72 h with constant stirring. The extract was obtained by filtration and the paste was then freeze dried at − 60 °C.

Assessment of biological properties of the aqueous extracts of the plants

Nitric oxide radical scavenging activity

The scavenging effect of aqueous extracts of each plant on nitric oxide radical was measured according to the method of Ebrahimzadeh et al. (2009). Aliquot (1 mL) of sodium nitroprusside (5 mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) was mixed with different concentrations of each plant aqueous extracts. This was incubated at room temperature for 150 min after which 0.5 mL of Griess reagent was added. The absorbance of the pink chromophore formed was read at 546 nm. Gallic acid and ascorbic acid were used as positive control. All experiment was done in triplicates. The percentage inhibition was calculated as follows:

Lipid peroxidation inhibition assay

The lipid peroxidation inhibition assay (LPI) was determined according to the method described by Liu et al. (2003) with a slight modification. Excised rat liver was homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and then centrifuged to obtain liposome. Aliquot (0.5 mL) of supernatant, 100 μL 10 mM FeSO4, 100 μL 0.1 mM ascorbic acid, and 0.3 mL of each plant aqueous extracts or standard at different concentrations were mixed to make the final volume of 1 ml. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Aliquot (1 mL) of (2%) TCA and 1.5 mL of (1%) TBA were added immediately after heating. Finally, the reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 15 min and cooled to room temperature. The absorbance was then taken at 532 nm. Percentage inhibition of lipid peroxidation (% LPI) was calculated as follows:

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control and Asample is the absorbance of the extractive/standard. Percentage of inhibition was plotted against concentration.

Ferric reducing power assay

Slightly modified assay method described by Shahi et al. (2020) was employed. Typically, aliquots of the aqueous extracts of each plant were mixed with 0.2 mM phosphate buffer (0.5 mL; pH 6.6) and 0.5 mL potassium ferricyanide (1% w/v). The mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. Trichloroacetic acid (10%, 2.5 mL) was added to the mixture and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. Aliquot (1 mL) of obtained supernatant was mixed with 1 mL FeCl3 (0.1%, 0.5 mL), and the absorbance was measured at 700 nm. Gallic acid and ascorbic acid were used as positive standard.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of aqueous extracts of each plant was carried out using the assay method of Kim and Minamikawa (1997) as described by Shahi et al. (2020) with slight modifications. Briefly, 0.1 mL of 10 mM EDTA, 0.01 mL of 10 mM FeCl3, 0.1 mL of 10 mM H2O2, 0.36 mL of 10 mM deoxyribose, 1.0 mL of aqueous extracts of each plant, 0.33 mL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4), and 0.1 mL of ascorbic acid were added sequentially. Resulting mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Aliquot (1.0 mL) of 5% TCA and 1.0 mL of 0.5% TBA were added to develop the pink chromogen measured at 532 nm. The standard was gallic acid and ascorbic acid. The percentage of hydroxyl radical scavenged was estimated using the following equation:

where Acontrol is the absorbance of control and Asample is the absorbance of sample solution.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

Assay method of Wu et al. (2003) with slight modifications was employed. Briefly, aliquots (1 mL) of varying concentrations (50–800 mg/mL) of aqueous extracts of each plant were added to 1 mM 2, 2 diphenyl-1-picryldydrazyl (DPPH) (1 mL) in methanol solution. Resulting mixtures were vortexed, centrifuged (2500 rpm for 10 min), and then incubated in a dark chamber for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 517 nm against DPPH control containing 1 mL methanol in place of the protein fractions. Gallic acid and ascorbic acid were used as positive standard. Inhibition of DPPH radical was calculated as a percentage using the expression:

where Ablank was standard absorbance and Asample was sample absorbance.

Scavenging of hydrogen peroxide

The ability of the aqueous extracts of each plant to scavenge hydrogen peroxide was determined according to Nabavi et al. (2008) and (2009). A solution of hydrogen peroxide (40 mM) was prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The concentration of hydrogen peroxide was determined by absorption at 230 nm using a spectrophotometer. Aqueous extracts of each plant (50–800 mg/ ml) in distilled water were added to a hydrogen peroxide solution (0.6 mL, 40 mM). The absorbance of hydrogen peroxide at 230 nm was determined after 10 min against a blank solution containing phosphate buffer without hydrogen peroxide. The percentage of hydrogen peroxide scavenging by the aqueous extracts of each plant and a standard compound was calculated as follows:

where Ao was the absorbance of the control and A1 was the absorbance in the presence of the sample of aqueous extracts of each plant and standard.

Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC–MS) analysis of the extract

The GC–MS analysis was carried out to determine the phytochemicals present in the aqueous extracts using GC–MS (Model: QP2010 plus Shimadzu, Japan) encompassing an AOC-20i auto-sampler and gas chromatograph interfaced to a mass spectrometer (GC–MS). The relative percentage of the analyte was expressed as a percentage with peak area normalization. Interpretation on the mass spectrum was conducted using the database of National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The fragmentation pattern spectra of the unknown components were compared with those of known components stored in the NIST library (NIST 11). The relative percentage of each phytochemical was calculated by comparing its average peak area to the total area. The name, molecular weight, and structure of the components of the test materials were ascertained.

In silico studies

Protein preparation

The crystal structures of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain (PDB ID 2AJF) with resolution 2.90 Å, ADP ribose phosphatase of NSP3 from SARS CoV-2 (PDB ID 6VXS) with resolution 2.03 Å, SARS-COV2 major protease (PDB ID 6LU7) with resolution 2.16 Å, and SARS CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB ID 7BTF) with resolution 2.95 Å were retrieved from the protein databank (www.rcsb.org). Before the docking and analysis, the crystal structures were processed by eliminating existing ligands and water molecules. Furthermore, missing hydrogen atoms were added using Autodock v4.2 program, Scripps Research Institute (Morris et al. 2009). Subsequently, non-polar hydrogens were merged while polar hydrogen was added and then saved into pdbqt format in preparation for molecular docking.

Ligand preparation

The SDF structures of phytochemical present in the extracts as identified by GC–MS were retrieved from the PubChem database (www.pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The phytochemicals were converted to mol2 chemical format. Polar hydrogens were added while non-polar hydrogens were merged with the carbons, and the internal degrees of freedom and torsions were set. The protein and ligand molecules were further converted to the dockable PDBQT format using Autodock tools.

Molecular docking

Docking of the phytochemicals to the targeted protein and determination of binding affinities was carried out using AutodockVina (Trott and Olson 2010). The PDBQT formats of the receptor and that of the phytochemicals were positioned at their respective columns, and the software was run. The binding affinities of phytochemicals for the protein target were recorded. The phytochemicals were then ranked by their affinity scores. The molecular interactions between the receptor and phytochemicals with most remarkable binding affinities were viewed with PYMOL.

ADMET analysis

The solubility, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and toxicological profiles of phytochemicals with the best docking score were computed based on their ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity) studies using pkCSM tool (http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction). The canonical SMILE molecular structures of the compounds used in the studies were obtained from PubChem (pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Results

Biological properties of the aqueous extracts of the plants

Nitric oxide inhibitory activity of the aqueous extracts of the plants

Figure 1 shows a significant increase in the nitric oxide inhibitory activity of all aqueous extracts of the selected medicinal plants at various concentrations used in this study. At 800 mg/ml, ALVA (aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina) displayed the highest nitric oxide inhibitory activity among the six plant extracts. Also, ALVA exhibited higher activity than ascorbic acid but not up to activity of the gallic acid. This confirms the possible anti-inflammatory potential of the aqueous extracts.

Fig. 1.

Nitric oxide inhibitory activity of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

Lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity of the aqueous extracts of the plants

The result in Fig. 2 revealed that the aqueous extracts of the selected plants demonstrated increased lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity with increase in the concentration of the extracts. However, at 800 mg/ml, ABAO (aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale) exhibited highest lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity when compared with other extracts. Similarly, ABAO displayed higher inhibitory activity than ascorbic acid when compared with the standard antioxidants used. In all, gallic acid has the highest activity. This study revealed that the extracts could mitigate the lipid peroxidation chain reactions and prevent oxidation of cellular macromolecules.

Fig. 2.

Lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

Ferric reducing power of the aqueous extracts of the plants

The result in Fig. 3 revealed the ferric reducing power of different concentrations of the aqueous extracts of the selected plants compared with standard antioxidants (ascorbic and tannic acids). At 800 mg/ml, all the extracts expect ALAO (aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius) displayed higher ferric radical reducing power than ascorbic acid when compared with standard antioxidants used. Of note, ABAO exhibited the highest ferric reducing power activity at 800 mg/mL among all the plant extracts used in the study.

Fig. 3.

Free radical reducing power of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

Hydroxyl radical scavenging ability of the aqueous extracts of the plants

Results in Fig. 4 showed that at 800 mg/ml, ALAI (aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica), ALCA (aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata), ALVA (aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina), and ABAO (aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale) have higher potent hydroxyl radical scavenging ability than ascorbic acid when compared with the standard antioxidants used. At all the tested concentrations, all the aqueous plant extracts displayed high hydroxyl radical scavenging ability with increase in their concentrations suggesting the extracts as potent source of antioxidant phytochemicals.

Fig. 4.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

DPPH inhibitory activity of the aqueous extracts of the plants

The result in Fig. 5 shows that all the aqueous extracts of the selected medicinal plants used in this study elicited impressive DPPH radical scavenging activities when compared with standard antioxidants: gallic acid and ascorbic acid. At 800 mg/ml, ALVA (aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina) exhibited the highest DPPH scavenging activity among all the extract used, followed by ABAO (aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale) and then ALCA (aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata) and ALPA. Although none of the extracts exhibited higher DPPH radical scavenging activity than the antioxidant standards used, their activity is significant, and this result depicted that they have substantial DPPH radical scavenging activity as the standard antioxidants.

Fig. 5.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

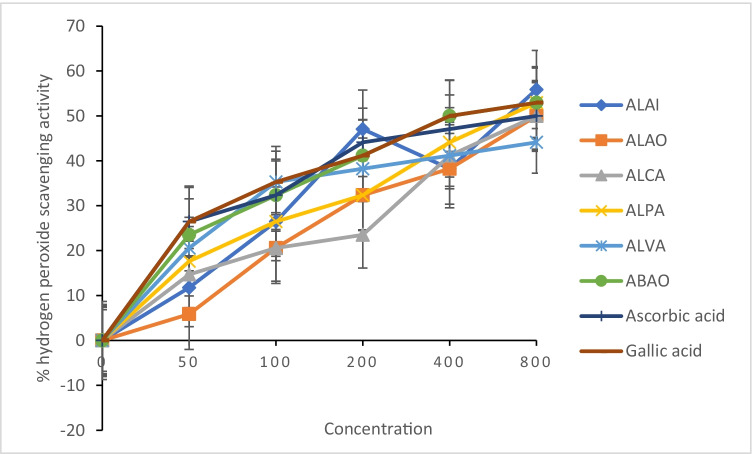

Hydrogen peroxide inhibitory activity of the aqueous extracts of the plants

Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity of all the aqueous extracts of the plants used in this study was presented in Fig. 6 as compared with the standard antioxidants (ascorbic and gallic acids). At tested concentrations, all the aqueous extracts efficiently scavenged hydrogen peroxide. Interestingly, at 800 mg/ml, ALAI exhibited the highest hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity when compared with the standard antioxidants used and other extracts. Similarly, all the extracts expect ALVA displayed higher hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity than ascorbic acid. This result indicated that all the extracts could play beneficial role in mitigating pathological conditions mediated by oxidative stress.

Fig. 6.

Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity of aqueous extracts of selected medicinal plants. ALAI, aqueous leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; ALAO, aqueous leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius; ALCA, aqueous leaf extract of Cassia alata; ALPA, aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus amarus; ALVA, aqueous leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina; ABAO, aqueous bark extract of Anacardium occidentale

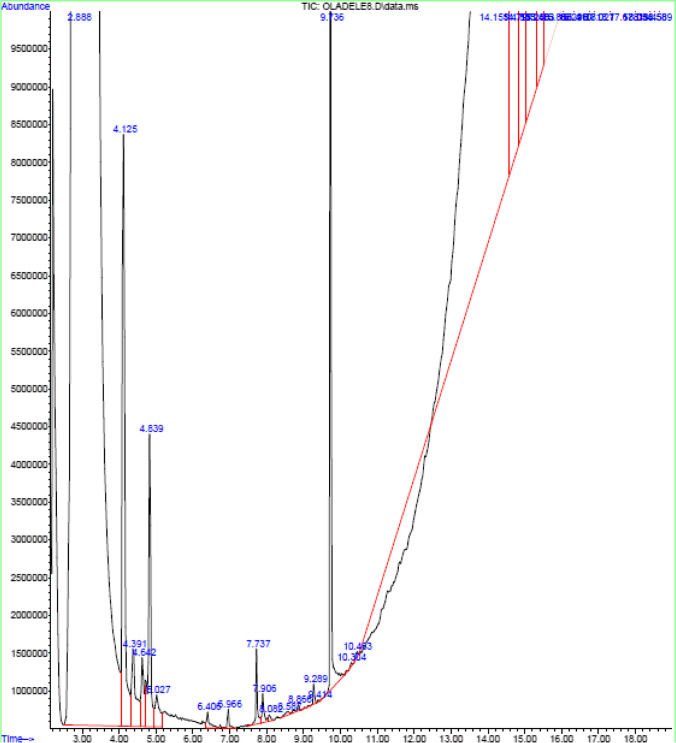

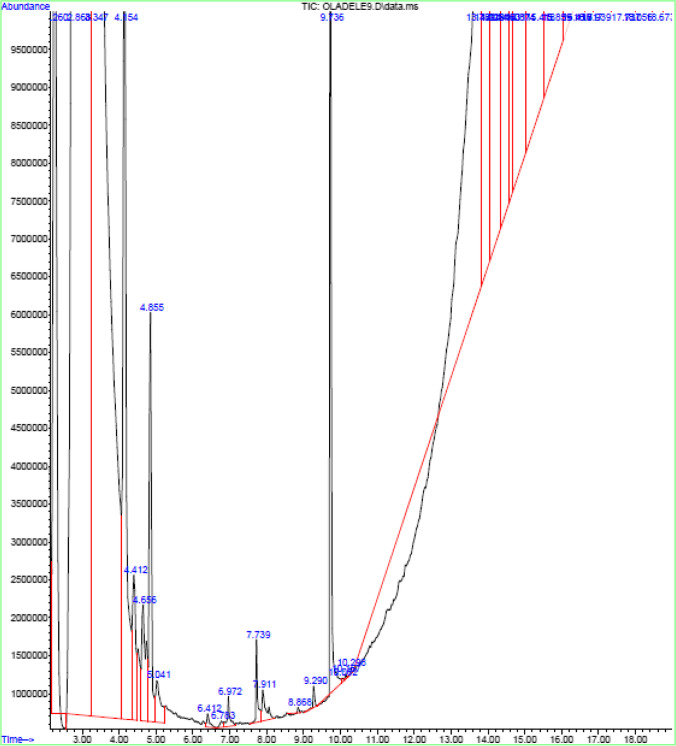

Phytochemical constituents and GCMS analysis of the extract

The preliminary qualitative phytochemical screening of extracts of the selected tropical plants used in this study revealed that the extracts are rich in phenol, flavonoids, coumarins, saponin, and alkaloids. The secondary metabolites profile of each of the extracts was detailed in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 as analysed using NIST 11 (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12). Some of the identified phytochemicals in the extracts have been reported to have antiapoptotic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects which are essential to mitigate inflammation, oxidative stress, and toxicity effects mediated by Coronavirus-2.

Table 1.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous leaf of Azadirachta indica

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethyl acetate | CCOC(= O)C | 8857 |

| 2 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | C = CCN | 7853 | |

| 3 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 4 | 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | CCCC(= O)C(C)C | 23,847 |

| 3,4-Dimethylpent-2-en-1-ol | CC(C)C(= CCO)C | 5,366,252 | |

| 1,1-Di(isobutyl)acetone | CC(C)CC(CC(C)C)C(= O)C | 551,338 | |

| 5 | Ethylbenzene | CCC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 7500 |

| o-Xylene | CC1 = CC = CC = C1C | 7237 | |

| 6 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester | CCC(= O)OCC(C)C | 10,895 | |

| n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 | |

| 7 | Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | C(CCl)N = C = O | 16,035 |

| 1-[N-Aziridyl]heptene-3 | CCCC = CCCN1CC1 | 5,364,877 | |

| 1-Heptene, 2-methyl- | CCCCCC(= C)C | 27,519 | |

| 8 | 1,3,3-Trimethyl-1-(4′-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyindane | CC1(CC(C2 = C1C = CC(= C2)OC)(C)C3 = CC = C(C = C3)OC)C | 624,568 |

|

1-[2,4-Bis(trimethylsiloxy)phenyl] -2-[(4-trimethylsiloxy)phenyl]prop an-1-one |

|||

| Chloromethyl octyl ether | CCCCCCCCOCCl | 534,743 | |

| 9 | Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 |

| Chloroacetic acid, 2-methylpentylester | |||

| Cyclohexanol, 1R-4-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 | |

| 10 | Butane, 2,2′-thiobis- | C(CCO)CO.C(CSCCO)O | 44,153,764 |

| 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-.beta.-D-erythro-hexopyranose | C1CC2OCC(C1O)O2 | 560,102 | |

| Boronic acid, ethyl-, bis(2-mercaptoethyl ester) | C1CC2OCC(C1O)O2 | 560,102 | |

| 11 | Silanol, trimethyl-, propanoate | CCC(= O)O[Si](C)(C)C | 519,321 |

| .beta.-D-Ribopyranoside, methyl 2, 3,4-tri-O-methyl- | COC1COC(C(C1OC)OC)OC | 21,140,439 | |

| Hexadecanoic acid, 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-, methyl ester | CC(C)CCCC(C)CCCC(C)CCCC(C)CC(= O)OC | 568,163 | |

| 12 | N1,N1-Dimethyl-N2-(1-phenyl–ethyl) -ethane-1,2-diamine | CC(C1 = CC = CC = C1)NCCN(C)C | 547,403 |

| 2-Nonanone | CCCCCCCC(= O)C | 13,187 | |

| 13 | 4-(2-Amino-3-cyano-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-yl)-3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid ethyl ester | CCOC(= O)C1 = C(C(= C(N1)C)C2C(= C(OC3 = C2C(= O)CCC3)N)C#N)C | 605,143 |

| Heptasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9,11,11,13,13-tetradecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,088 | |

|

1H-Indole-2-carboxylic acid, 6-(4-ethoxyphenyl)-3-methyl-4-oxo-4,5,6 ,7-tetrahydro-, isopropyl ester |

CCOC1 = CC = C(C = C1)C2CC3 = C(C(= C(N3)C(= O)OC(C)C)C)C(= O)C2 | 4,916,205 | |

| 14 | Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9, 11,11,13,13,15,15-hexadecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,087 |

| Heptasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9,11,11,13,13-tetradecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,088 | |

|

Furo[2′,3′:4,5]thiazolo[3,2-g]purine-8-methanol, 4-amino-6.alpha.,7, 8,9a-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-, [6aS-( 6a.alpha.,7.alpha.,8.beta.,9a.alph a.)]- |

|||

| 15 | Dodecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 3893 |

| Methyl 6-O-[1-methylpropyl]-.beta. -d-galactopyranoside | CCC(C)OCC1C(C(C(C(O1)OC)O)O)O | 22,213,632 | |

| Nonanoic acid | CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 8158 | |

| 16 | n-Decanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 2969 |

| Trisilane | C[Si](C)(C)[Si](C)(C)[Si](C)(C)C1 = CC = CC2 = CC = CC = C21 | 142,270 | |

| 4a-Methyl-6,8-dioxa-3-thia-bicyclo(3,2,1)octane | 50,469,286 | ||

| 17 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1,1-Diisobutoxy-isobutane | CC(C)COC(C(C)C)OCC(C)C | 545,267 | |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 | |

| 18 | Undec-10-ynoic acid | C#CCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 31,039 |

| 19 | 1-Pentadecyne | CCCCCCCCCCCCCC#C | 69,825 |

| 20 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 21 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 |

| 1-Methoxymethoxy-oct-2-yne | CCCCCC#CCOCOC | 542,329 | |

| Thioctic acid | C1CSSC1CCCCC(= O)O | 864 | |

| 22 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | CCCCCC = CCC = CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 5,280,450 |

| 23 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 24 | Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylet hyl ester | CC(C1CCCC1)OC(= O)CCl | 543,343 |

| 25 | (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene) -cyclohexane | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 |

| 26 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-2-oxa-spiro[5.5]undecan-5-one | C1CCC2(CC1)COC(CC2 = O)(C(F)(F)F)O | 557,008 | |

| 27 | Cyclohexanol, 2-(2-propynyloxy)-, trans- | C#CCOC1CCCCC1O | 12,522,342 |

| 5-Methoxymethoxyhexa-2,3-diene | CC = C = CC(C)OCOC | 542,425 | |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| 28 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-2-oxa- spiro[5.5]undecan-5-one | C1CCC2(CC1)COC(CC2 = O)(C(F)(F)F)O | 557,008 | |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| 29 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | CCCCCC = CCC = CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 5,280,450 |

| 30 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 1-Methoxymethoxy-oct-2-yne | CCCCCC#CCOCOC | 542,329 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 31 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2 (hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 32 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-2-oxa- spiro[5.5]undecan-5-one | C1CCC2(CC1)COC(CC2 = O)(C(F)(F)F)O | 557,008 | |

| Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylethyl ester | CC(C1CCCC1)OC(= O)CCl | 543,343 | |

| 33 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 34 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

Table 2.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous leaf of Corchorus olitorius

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethyl acetate | CCOC(= O)C | 8857 |

| Acetic acid, pentyl ester | CCCCCOC(= O)C | 12,348 | |

| 2 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | C = CCN | 7853 | |

| 3 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | C = CCN | 7853 | |

| 4 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 5 | 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | CCCC(= O)C(C)C | 23,847 |

| Butyric acid, 2,2-dimethyl-, vinyl ester | CCC(C)(C)C(= O)OC = C | 537,729 | |

| 6 | o-Xylene | CC1 = CC = CC = C1C | 7237 |

| Benzene, 1,3-dimethyl- | CC1 = CC(= CC = C1)C | 7929 | |

| 7 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester | CC(C(C)(C)C)OC = O | 54,488,145 | |

| 8 | 4-Ethyl-4-methyl-5-methylene-[1,3] dioxolan-2-one | CCC1(C(= C)OC(= O)O1)C | 544,710 |

| 1,1-Cyclohexanedicarbonitrile | C1CCC(CC1)(C#N)C#N | 544,561 | |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | C(CCl)N = C = O | 16,035 | |

| 9 | Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl- | CC(= O)NC1CCCCC1 | 14,301 |

| Acetamide, N-(4-hydroxycyclohexyl) -, cis- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(CC1)O | 90,074 | |

| L-Lyxose | C(C(C(C(C = O)O)O)O)O | 644,176 | |

| 10 | 12,12-Dimethoxydodecanoic acid, methyl ester | COC(CCCCCCCCCCC(= O)OC)OC | 554,421 |

| Hexadecane, 1,1-dimethoxy- | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(OC)OC | 76,037 | |

| 1-Propene, 3,3-dichloro- | C = CC(Cl)Cl | 11,244 | |

| 11 | Isopropyl isothiocyanate | CC(C)N = C = S | 75,263 |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | CCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(= O)C(= CC)C | 91,701,893 | |

| 3-Phenylpropionic acid, 4-methoxy- 2-methylbutyl ester | CC(CCOC)COC(= O)CCC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 91,702,047 | |

| 12 | Hexasiloxane, 11,11-dodecamethyl- | C[Si](C)(O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)Cl)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)Cl | 553,580 |

|

Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9, 11,11,13,13,15,15 hexadecamethyl- |

C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,087 | |

| 9-Bromononanoic acid | C(CCCCBr)CCCC(= O)O | 548,221 | |

| 13 | Hexasiloxane, tetradecamethyl- | C[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)C | 7875 |

| Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9, 11,11,13,13,15,15-hexadecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,087 | |

| 1-Butyl-3,4-dihydroxy- | CCCCCNC(= O)C1C(C(CN1CCCC)O)O | 6,420,934 | |

| pyrrolidine- 2,5-dione | C1C(C(= O)N(C1 = O)C2 = CC = C(C = C2)F)SCCN | 2,756,427 | |

| 14 | 11-Bromoundecanoic acid | C(CCCCCBr)CCCCC(= O)O | 17,812 |

| 2-Ethylacridine | CCC1 = CC2 = CC3 = CC = CC = C3N = C2C = C1 | 610,161 | |

| N-Cyclododecylacetamide | CC(= O)NC1CCCCCCCCCCC1 | 548,224 | |

| 15 | Octadecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 5281 |

| Polygalitol | C1C(C(C(C(O1)CO)O)O)O | 64,960 | |

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl-2-[(2-furanylmethyl)thio]- | C1CCC(CC1)NC(= O)CSCC2 = CC = CO2 | 5,298,618 | |

| 16 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 | |

| 1,1-Diisobutoxy-isobutane | CC(C)COC(C(C)C)OCC(C)C | 545,267 | |

| 17 | 1-Butyl-3,4-dihydroxy-pyrrolidine- 2,5-dione | CCCCN1C(= O)C(C(C1 = O)O)O | 6,420,934 |

| L-Galactose, 6-deoxy- | CC(C(C(C(C = O)O)O)O)O | 3,034,656 | |

| Nonanoic acid | CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 8158 | |

| 18 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | CCCCCC = CCC = CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 5,280,450 |

| 9-Octadecyne | CCCCCCCCC#CCCCCCCCC | 141,998 | |

| Undec-10-ynoic acid | C#CCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 31,039 | |

| 19 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 20 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| Thioctic acid | C1CSSC1CCCCC(= O)O | 864 | |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| 21 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 |

| 1-Methoxymethoxy-oct-2-yne | CCCCCC#CCOCOC | 542,329 | |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| 22 | Thioctic acid | C1CSSC1CCCCC(= O)O | 864 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene -cyclohexane | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 | |

| 23 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

|

1-Naphthalenemethanol, decahydro-5 -(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-3-pentenyl)-1 ,4a-dimethyl-6-methylene-, [1S-[1.alpha.,4a.alpha.,5.alpha.(E),8a.beta.]]- |

CC(= CCO)CCC1C(= C)CCC2C1(CCCC2(C)CO)C | 5,316,778 | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-2-oxa spiro[5.5]undecan-5-one | C1CCC2(CC1)COC(CC2 = O)(C(F)(F)F)O | 557,008 | |

| 24 |

1-Naphthalenemethanol, decahydro-5 -(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-3-pentenyl)-1 ,4a-dimethyl-6-methylene-, [1S-[1.alpha.,4a.alpha.,5.alpha.(E),8a.be ta.]]- |

CC(= CCO)CCC1C(= C)CCC2C1(CCCC2(C)CO)C | 5,316,778 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| 25 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1(CCC1 = O)C2CO2 | 534,052 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 26 | Borolane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-1,2,2-tris(1-methylethyl)- | B1(CC(C(C1(C(C)C)C(C)C)CC)C)C(C)C | 535,085 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 27 | 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

| Cyclohexanol, 2-(2-propynyloxy)-, trans- | C#CCOC1CCCCC1O | 12,522,342 | |

| Spiro[2.3]hexan-4-one, 5,5-diethyl | CCC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)CC | 534,343 | |

| 28 |

3- Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan -one |

C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| Cyclododecanol, 1-aminomethyl- | C1CCCCCC(CCCCC1)(CN)O | 533,851 | |

| 29 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1(CCC1 = O)C2CO2 | 534,052 |

| Spiro[2.3]hexan-4-one, 5,5-diethyl | CCC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)CC | 534,343 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 30 | Cyclohexanol, 2-(2-propynyloxy)-, trans- | C#CCOC1CCCCC1O | 12,522,342 |

| 8-Azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2-carboxylic acid, 3-hydroxy-8-methyl-, (2-endo,3-exo)- | CN1C2CC1C(C(C(C2)O)C(= O)[O-])O | 54,613,783 | |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1(CCC1 = O)C2CO2 | 534,052 | |

| 31 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CCC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)CC | 534,343 | |

| 5-Methoxymethoxyhexa-2,3-diene | CC = C = CC(C)OCOC | 542,425 | |

| 32 | Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CCC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)CC | 534,343 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxyl methyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | |||

| 5-Methoxymethoxyhexa-2,3-diene | CC = C = CC(C)OCOC | 542,425 | |

| 33 | Borolane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-1,2,2-tris(1-methylethyl)- | B1(CC(C(C1(C(C)C)C(C)C)CC)C)C(C)C | 535,085 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 | |

| Thioctic acid | C1CSSC1CCCCC(= O)O | 864 | |

| 34 | 5-Methoxymethoxyhexa-2,3-diene | CC = C = CC(C)OCOC | 542,425 |

| Cyclohexanol, 2-(2-propynyloxy)-, trans- | C#CCOC1CCCCC1O | 12,522,342 | |

| Ethane, 1,2-dichloro-1,1,2-trifluoro- | C(C(F)(F)Cl)(F)Cl | 9631 | |

| 35 | 5-Methoxymethoxyhexa-2,3-diene | CC = C = CC(C)OCOC | 542,425 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2 propenyl)- | CC(= CC1CCCCC1 = O)C | 592,361 | |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-2-oxa-spiro[5.5]undecan-5-one | C1CCC2(CC1)COC(CC2 = O)(C(F)(F)F)O | 557,008 | |

| 36 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| Spirohexan-4-one, 5,5-dimethyl- | CCC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)CC | 534,343 | |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC23C(C1)CCC(= O)C2O3 | 548,904 |

Table 3.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous leaf of Cassia alata

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 2 | 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | CCCC(= O)C(C)C | 23,847 |

| Acetaldehyde, butylhydrazone | CCCCNN = CC | 9,601,789 | |

| Butyric acid, 2,2-dimethyl-, vinyl ester | CCC(C)(C)C(= O)OC = C | 537,729 | |

| 3 | o-Xylene | CC1 = CC = CC = C1C | 7237 |

| 1-Oxa-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-4-oxyl, 3,3-dimethyl-8-oxo- | CC1(COC2([N +]1 = O)CCC(= O)CC2)C | 6,420,654 | |

| 1,3,2-Dioxaborinane, 2-ethyl-5,5-dimethyl- | B1(OCC(CO1)(C)C)CC | 544,611 | |

| 4 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester | CCC(= O)OCC(C)C | 10,895 | |

| 5 | Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(2-furfurylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | CC1 = C(C(= O)N(N1C)C2 = CC = CC = C2)N = CC3 = CC = CO3 | 624,533 |

| Cyclohexaneacetic acid, butyl este | CCCCOC(= O)CC1CCCCC1 | 251,210 | |

|

Furo[2′,3′:4,5]thiazolo[3,2-g]purine-8-methanol, 4-amino-6.alpha.,7,8,9a-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-, [6aS-(6a.alpha.,7.alpha.,8.beta.,9a.alph a.)]- |

|||

| 6 | 6-Azaestra-1,3,5(10),6,8-pentaen-1,7-one, 3-methoxy- | ||

| Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(2-furfurylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | CC1 = C(C(= O)N(N1C)C2 = CC = CC = C2)N = CC3 = CC = CO3 | 624,533 | |

| 1,3,3-Trimethyl-1-(4′-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyindane | CC1(CC(C2 = C1C = CC(= C2)OC)(C)C3 = CC = C(C = C3)OC)C | 624,568 | |

| 7 | Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 |

| Cyclohexaneacetic acid, butyl este | CCCCOC(= O)CC1CCCCC1 | 251,210 | |

| Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | C1CCC(C1)CCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 534,549 | |

| 8 | Hexyl 2-hydroxyethyl sulfide | CCCCCCSCCO | 90,519 |

| D-Arabinitol | C(C(C(C(CO)O)O)O)O | 94,154 | |

| Ribitol | C(C(C(C(CO)O)O)O)O | 6912 | |

| 9 | Silanol, trimethyl-, propanoate | CCC(= O)O[Si](C)(C)C | 519,321 |

|

6-Methyl-2-oxo-4-(4-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-pyrim idine-5-carboxylic acid 2-methylsu lfanyl-ethyl ester |

|||

| 2-Octanol, 8,8-dimethoxy-2,6-dimethyl- | CC(CCCC(C)(C)O)CC(OC)OC | 31,272 | |

| 10 | Ethanol, 2-phenoxy-, propanoate | CCC(= O)OCCOC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 31,954 |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | CCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(= O)C(= CC)C | 91,701,893 | |

| 11 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 |

Table 4.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous leaf of Phyllanthus amarus

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 2 | 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | CCCC(= O)C(C)C | 23,847 |

| Butyric acid, 2,2-dimethyl-, vinylester | CCC(C)(C)C(= O)OC = C | 537,729 | |

| 2-Methylvaleroyl chloride | CCCC(C)C(= O)Cl | 107,385 | |

| 3 | o-Xylene | CC1 = CC = CC = C1C | 7237 |

| 1-Hexene, 3,4-dimethyl- | CCC(C)C(C)C = C | 140,134 | |

| 2H-Pyran-2-one, tetrahydro-5,6-dimethyl-, trans- | CC1CCC(= O)OC1C | 11,029,861 | |

| 4 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-ylester | CC(C(C)(C)C)OC = O | 54,488,145 | |

| 5 | Pentane, 1-bromo-3,4-dimethyl- | CC(C)C(C)CCBr | 544,665 |

| Butanoic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)CCC | 7983 | |

| Cyclododecylamine | C1CCCCCC(CCCCC1)N | 2897 | |

| 6 | Pentane, 1-bromo-3,4-dimethyl- | CC(C)C(C)CCBr | 544,665 |

| Pentane, 2,3-dimethyl- | CCC(C)C(C)C | 11,260 | |

| 2,4-Dipropyl-5-ethyl-1,3-dioxane | CCCC1C(COC(O1)CCC)CC | 221,917 | |

| 7 | n-Butyl isobutyl sulfide | CCCCSCC(C)C | 525,418 |

| 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-.beta.-D-erythro-hexopyranose | C1CC2OCC(C1O)O2 | 560,102 | |

| Decanoic acid, propyl ester | CCCCCCCCCC(= O)OCCC | 121,739 | |

| 8 | 6-Bromohexanoic acid, hexyl ester | CCCCCCOC(= O)CCCCCBr | 543,783 |

| 1,3-Hexanediol, 2-ethyl- | CCCC(C(CC)CO)O | 7211 | |

| 1-Undecene, 2-methyl- | CCCCCCCCCC(= C)C | 87,689 | |

| 9 | 1,3-Dioxane, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | CCC1OCC(CO1)C | 141,976 |

| Silanol, trimethyl-, propanoate | CCC(= O)O[Si](C)(C)C | 519,321 | |

| .beta.-D-Ribopyranoside, methyl 2, 3,4-tri-O-methyl- | COC1COC(C(C1OC)OC)OC | 21,140,439 | |

| 10 | Propane, 1-isothiocyanato- | CCCN = C = S | 69,403 |

| Butane, 1,1′-[ethylidenebis(oxy)]bis- | CCC(C)COC(C)OCC(C)CC | 551,340 | |

| 11 | 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 |

| Para methadione | CCC1(C(= O)N(C(= O)O1)C)C | 8280 | |

| 12 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 | |

| Neopentyl isothiocyanate | CC(C)(C)CN = C = S | 136,393 |

Table 5.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous leaf of Vernonia amygdalina

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethyl acetate | CCOC(= O)C | 8857 |

| 2 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | C = CCN | 7853 | |

| 3 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| Aziridine, 2-methyl- | CC1CN1 | 6377 | |

| 4 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 5 | Ethanamine, N-pentylidene- | CCCCC = NCC | 544,805 |

| 2-Propanone, propylhydrazone | CCCNN = C(C)C | 139,018 | |

| Oxirane, (1-methylethyl)- | CC(C)C1CO1 | 102,618 | |

| 6 | Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(5-hydroxymethylfurfur-2-ylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | CC1 = C(C(= O)N(N1C)C2 = CC = CC = C2)N = CC3 = CC = C(O3)CO | 544,706 |

| Ethylbenzene | CCC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 7500 | |

| 7 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

|

Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester |

CC(C(C)(C)C)OC = O | 54,488,145 | |

| 8 | Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | C(CCl)N = C = O | 16,035 |

| 1-Hexene, 3,4-dimethyl- | CCC(C)C(C)C = C | 140,134 | |

| 3,4,5-Trimethyldihydrofuran-2-one | CC1C(C(= O)OC1C)C | 544,600 | |

| 9 | Cyclohexane acetic acid, butyleste | ||

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl- | CC(= O)NC1CCCCC1 | 14,301 | |

| Pentane, 1-bromo-3,4-dimethyl- | CC(C)C(C)CCBr | 544,665 | |

| 10 | N-Cyclododecylacetamide | CC(= O)NC1CCCCCCCCCCC1 | 548,224 |

| Cyclohexaneacetic acid, butyl este | |||

| Trisilane | C[Si](C)(C)[Si](C)(C)[Si](C)(C)C1 = CC = CC2 = CC = CC = C21 | 142,270 | |

| 11 | 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-.beta.-D-erythro-hexopyranose | C1CC2OCC(C1O)O2 | 560,102 |

| 2-Butenoic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C = CC | 5,366,039 | |

| Morpholine | C1COCCN1 | 8083 | |

| 12 | Dimethyl{bis[(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)oxy]}silane | CC(= CCO[Si](C)(C)OCC = C(C)C)C | 91,697,225 |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | CC(= O)OCC(C)(C)C | 13,552 | |

| Allyl(2-butoxy)dimethylsilane | CCC(C)O[Si](C)(C)CC = C | 554,670 | |

| 13 | Succinic acid, hexyl 3-oxobut-2-yl-ester | CCCCCCOC(= O)CCC(= O)OC(C)C(= O)C | 91,702,832 |

| .beta.-D-Xylopyranoside, methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-methyl- | COC1COC(C(C1OC)OC)OC2C(C(COC2OC)OC)OC | 91,726,683 | |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | CCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(= O)C(= CC)C | 91,701,893 | |

| 14 | Thiazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | CCC1 = NCCS1 | 86,896 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 | |

| Cyclopentane, 1-methyl-2-(4-methylpentyl)-, trans- | CC1CCCC1CCCC(C)C | 6,432,631 | |

| 15 | Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | C1CCC(C1)CCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 534,549 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 | |

| Pentadecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 13,849 | |

| 16 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 | |

| 17 | Dodecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 3893 |

|

Carbamic acid, [1-(hydroxymethyl)-2-phenylethyl]-, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester, (s)- |

CC(C)(C)OC(= O)NC(CC1 = CC = CC = C1)CO | 2,733,675 | |

| 8-Chlorocapric acid | C(CCCC(= O)O)CCCCl | 548,250 | |

| 18 | Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl-2-[(2-furanylmethyl)thio]- | C1CCC(CC1)NC(= O)CSCC2 = CC = CO2 | 5,298,618 |

| n-Decanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 2969 | |

| Pentadecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 13,849 | |

| 19 | Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl-2-[(2-furanylmethyl)thio]- | C1CCC(CC1)NC(= O)CSCC2 = CC = CO2 | 5,298,618 |

| Propane, 1,2-dichloro-2-fluoro- | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 13,849 | |

| 1-Butyl-3,4-dihydroxy-pyrrolidine- 2,5-dione | CCCCN1C(= O)C(C(C1 = O)O)O | 6,420,934 | |

| 20 | 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| Ethanol, 2-bromo- | C(CBr)O | 10,898 | |

| 21 | Borolane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-1,2,2-tris(1-methylethyl)- | B1(CC(C(C1(C(C)C)C(C)C)CC)C)C(C)C | 535,085 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 22 | Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 23 | Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 | |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(1-mercapto-1-methylethyl)-5-methyl-, trans- | CC1CCC(C(= O)C1)C(C)(C)S | 6,951,713 | |

| 24 | Cyclohexanone, 2-(1-mercapto-1-methylethyl)-5-methyl-, trans- | CC1CCC(C(= O)C1)C(C)(C)S | 6,951,713 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 25 | 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | C1CC(CCC1CN)CN | 17,354 |

| Borolane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-1,2,2-tris(1-methylethyl)- | B1(CC(C(C1(C(C)C)C(C)C)CC)C)C(C)C | 535,085 | |

| (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene)-cyclohexane | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 | |

| 26 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 |

| Borolane, 3-ethyl-4-methyl-1,2,2-tris(1-methylethyl)- | B1(CC(C(C1(C(C)C)C(C)C)CC)C)C(C)C | 535,085 | |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 27 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 | |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| 28 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 | |

| 29 | 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 |

| 2-Tetradecanol | CCCCCCCCCCCCC(C)O | 20,831 | |

| 2H-1,2,3-Triazol-4-amine, 2-cyclohexyl-5-nitro-, 1-oxide | 249,914,956 | ||

| 30 | 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 31 | Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 |

| Oxonin, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-, (Z,Z)32 | |||

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| 32 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC = COC = CC1 | 5,365,711 | |

| 33 | Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 |

| (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene)25-cyclohexane | COCOC(CCC = C1CCCCC1)C#C | 542,331 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

Table 6.

GC–MS analysis of aqueous bark of Anacardium occidentale

| S/N | Compound | Canonical SMILES | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethyl acetate | CCOC(= O)C | 8857 |

| 2 | 2-Propenal | C = CC = O | 7847 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | C = CCN | 7853 | |

| 3 | Acetic acid, butyl ester | CCCCOC(= O)C | 31,272 |

| 4 | Ethanamine, N-pentylidene- | CCCCC = NCC | 544,805 |

| Acetaldehyde, butylhydrazone | CCCCNN = CC | 9,601,789 | |

| 2-Propanone, propylhydrazone | CCCNN = C(C)C | 139,018 | |

| 5 | p-Xylene | CC1 = CC = C(C = C1)C | 7809 |

| o-Xylene | CC1 = CC = CC = C1C | 7237 | |

| Ethylbenzene | CCC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 7500 | |

| 6 | n-Butyl ether | CCCCOCCCC | 8909 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester | CC(C(C)(C)C)OC = O | 54,488,145 | |

| Ethanol, 2-butoxy- | CCCCOCCO | 8133 | |

| 7 | Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(5-hydroxymethylfurfur-2-ylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | CC1 = C(C(= O)N(N1C)C2 = CC = CC = C2)N = CC3 = CC = C(O3)CO | 544,706 |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | C(CCl)N = C = O | 16,035 | |

| 1-Oxa-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-4-oxyl, 3,3-dimethyl-8-oxo- | CC1(COC2([N +]1 = O)CCC(= O)CC2)C | 6,420,654 | |

| 8 | 1-Octene, 2-methyl- | CCCCCCC(= C)C | 78,335 |

| 1-Pentene, 5-chloro-4-(chloromethyl)-2,4-dimethyl- | CC(= C)CC(C)(CCl)CCl | 544,717 | |

| 4-t-Butylcyclohexylamine | CC(C)(C)C1CCC(CC1)N | 79,396 | |

| 9 | Butane, 2,2′-thiobis- | C(CCO)CO.C(CSCCO)O | 44,153,764 |

| Dimethylamine, N-(neopentyloxy)- | CC(C)(C)CON(C)C | 548,341 | |

| 3-Deoxy-d-mannitol | C(C(CO)O)C(C(CO)O)O | 560,035 | |

| 10 | Silane, trimethyl(2-methylpropoxy) | CC(C)CO[Si](C)(C)C | 519,538 |

| 1-Propanol, 2,2-dimethyl-, acetate | CC(= O)OCC(C)(C)C | 13,552 | |

| Propanoic acid, dimethyl(chloromethyl)silyl ester | CCC(= O)O[Si](C)(C)CCl | 554,674 | |

| 11 | 2-Butylthiazoline | CCCCC1 = NCCS1 | 206,597 |

| 4.beta.,5-Dimethyl-6,8-dioxa-3-thiabicyclo(3,2,1)octane 3-oxide | CC1C2(OCC(O2)CS1 = O)C | 538,769 | |

| Succinic acid, butyl decyl ester | CCCCCCCCCCOC(= O)CCC(= O)OCCCC | 91,701,657 | |

| 12 | 1-Pentadecene, 2-methyl- | CCCCCCCCCCCCCC(= C)C | 520,456 |

| Pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine, 4-phenyl- | C1 = CC = C(C = C1)C2 = C3C = CC = NC3 = NC = N2 | 610,177 | |

| 1-Benzenesulfonyl-1H-pyrrole | C1 = CC = C(C = C1)S(= O)(= O)N2C = CC = C2 | 140,146 | |

| 13 | Acetamide, N-(4-hydroxycyclohexyl) -, cis- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(CC1)O | 90,074 |

| Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9,11,11,13,13,15,15-hexadecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,087 | |

| 1H-Indole, 5-methyl-2-phenyl- | CC1 = CC2 = C(C = C1)NC(= C2)C3 = CC = CC = C3 | 83,247 | |

| 14 | Thiazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | CCC1 = NCCS1 | 86,896 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 | |

| Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | C1CCC(C1)CCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 534,549 | |

| 15 | Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | C1CCC(C1)CCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 534,549 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | CC(= O)NC1CCC(C2C1O2)OC = O | 537,204 | |

| Decanoic acid, silver(1 +) salt | 319,368,662 | ||

| 16 | Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | CCCCOC(CCC)OCCCC | 22,210 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | CCCCOC(CCC)OCC(C)C | 545,190 | |

| Neopentyl isothiocyanate | CC(C)(C)CN = C = S | 136,393 | |

| 17 | Nonanoic acid | CCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 8158 |

| .alpha.-D-Glucopyranose, 4-O-.beta.-D-galactopyranosyl | C(C1C(C(C(C(O1)OC2C(OC(C(C2O)O)O)CO)O)O)O)O.O | 522,113 | |

|

n- Decanoic acid |

CCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 2969 | |

| 18 | Tridecanoic acid | CCCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)O | 12,530 |

| Octasiloxane, 1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7,9,9,11,11,13,13,15,15-hexadecamethyl- | C[Si](C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)(C)O[Si](C)C | 6,329,087 | |

| 19 | Z,E-7,11-Hexadecadien-1-yl acetate | CCCCC = CCCC = CCCCCCCOC(= O)C | 5,363,282 |

|

2(1H)-Naphthalenone, octahydro-4a- methyl-7-(1-methylethyl)-, (4a.alp ha.,7.beta.,8a.beta.) - |

|||

|

3,6-Epoxy-2H,8H-pyrimido[6,1-b][1,3]oxazocine-8,10(9H)-dione, 4-(ace tyloxy)-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-11-meth yl-, [3R-(3.alpha.,4.beta.,6.alpha .)]- |

|||

| 20 | 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

| Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylethyl ester | CC(C1CCCC1)OC(= O)CCl | 543,343 | |

| Dodecanoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | CCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)OCC(COC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC)OC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC | 10,851 | |

| 21 | 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | C1CCC = COC = CC1 | 5,365,711 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 22 | Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| Spiro[2.3]hexan-4-one, 5,5-diethyl | CC1(CC2(C1 = O)CC2)C | 534,214 | |

| 23 | Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 | |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 24 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 25 | 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 26 | 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylethyl ester | CC(C1CCCC1)OC(= O)CCl | 543,343 | |

| 27 | 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | C = CCC1CCCCC1 = O | 78,944 | |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | C1C2C(CC2 = O)C3C1O3 | 556,833 | |

| 28 | Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | CC#CC(= O)NC | 549,138 | |

| 29 | Dodecanoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | CCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)OCC(COC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC)OC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC | 10,851 |

| [1,2,4]Triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-5(4H)-one, 7-amino-4-methyl- | CN1C(= O)C = C(N2C1 = NC = N2)N | 16,766,882 | |

| 30 | Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 31 | Dodecanoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | CCCCCCCCCCCC(= O)OCC(COC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC)OC(= O)CCCCCCCCCCC | 10,851 |

| Cyclododecanol, 1-aminomethyl- | C1CCCCCC(CCCCC1)(CN)O | 533,851 | |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 32 | Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | CCCCCCC(CCO)CCOC | 542,174 | |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | CC1CCC(C1CO)C(C)CO | 101,710 | |

| 33 | Cyclododecanol, 1-aminomethyl- | C1CCCCCC(CCCCC1)(CN)O | 533,851 |

| 1H-Imidazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | CCC1 = NCCN1 | 13,590 | |

| 1-Phenyloxycarbonyl-7-pentyl-7-aza bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane |

Fig. 7.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous leaf of Azadirachta indica

Fig. 8.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous leaf of Corchorus olitorius

Fig. 9.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous leaf of Cassia alata

Fig. 10.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous leaf of Phyllanthus amarus

Fig. 11.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous leaf of Vernonia amygdalina

Fig. 12.

GC–MS spectrum of aqueous bark of Anacardium occidentale

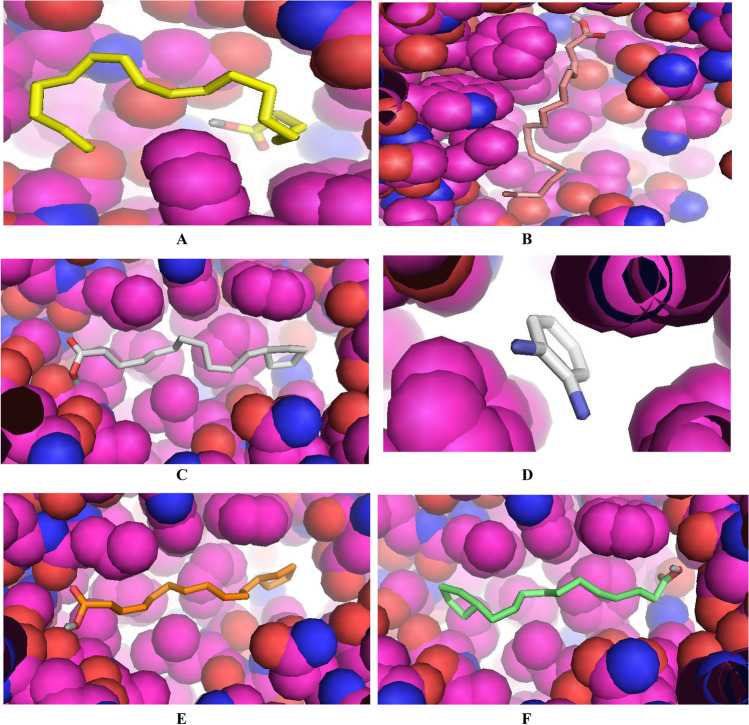

Molecular docking analysis

The molecular docking analysis and visualization of the selected proteins of Coronavirus-2 with the phytochemicals identified from the six medicinal plants (Azadirachta indica, Corchorus olitorius, Cassia alata, Phyllanthus amarus, Vernonia amygdalina, and Anacardium occidentale) were showed in Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. The results revealed that the phytochemicals demonstrated high binding affinities against the proteins. This indicates that these phytochemicals could have substantial inhibitory effects against these proteins thus mitigating their pathogenic properties, ultimately leading to suppression of the pathogenesis of COVID-19.

Table 7.

Molecular docking score of the phytochemicals of Azadirachta indica against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene) -cyclohexane | − 5.8 | − 4.3 | − 5.1 | − 4.8 |

| 1,1-Di(isobutyl)acetone | − 5.5 | − 4.9 | − 5 | − 5.6 |

| 1,1-Diisobutoxy-isobutane | − 4.9 | − 4.8 | − 5 | − 5.2 |

| 1,3,3-Trimethyl-1-(4′-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyindane | − 7 | − 6.4 | − 7.3 | − 7.8 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | − 4.9 | − 4.6 | − 4.7 | − 4.7 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | − 4.6 | − 4 | − 4.5 | − 4.5 |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | − 3.4 | − 3.3 | − 3 | − 3.8 |

| 1-Methoxymethoxy-oct-2-yne | − 4.9 | − 3.9 | − 3.9 | − 4.6 |

| 1-Pentadecyne | − 4.2 | − 3.6 | − 4.1 | − 4.3 |

| Cyclohexanol, 1R-4-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy- | − 5.3 | − 5.1 | − 4.7 | − 4.8 |

| 1RA23A_Cyclohexanol | − 5.5 | − 5.2 | − 4.8 | − 5.1 |

| Butane, 2,2′-thiobis- | − 3.8 | − 3.4 | − 4 | − 4 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | − 4.5 | − 3.5 | − 3.8 | − 4.3 |

| 1-Heptene, 2-methyl- | − 5 | − 3.6 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | − 4.4 | − 3.8 | − 3.9 | − 4.6 |

| 2_methylphenylester | − 5.9 | − 6.1 | − 6.2 | − 6.4 |

| 2-Nonanone | − 4.4 | − 3.8 | − 4.1 | − 4.7 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | − 3.4 | − 3.3 | − 2.9 | − 3.5 |

| 2-Propenal | − 3 | − 2.6 | − 2.4 | − 3.2 |

| 3,4-Dimethylpent-2-en-1-ol | − 4.5 | − 4.4 | − 4.2 | − 4.7 |

| 3_Hydroxy_3_trifluoromethyl_2_oxa_ spiro[5_5]undecan_5_one | − 7.1 | − 6.3 | − 6.5 | − 6.9 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | − 5.8 | − 5.3 | − 5.2 | − 6.1 |

| 4-(2-Amino-3-cyano-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-yl)-3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid ethyl ester_yl)_3_5_dimethyl_1H_pyrrole_2_carboxylic acid ethyl ester | − 6.8 | − 7.6 | − 7.9 | − 7.5 |

| 4a-Methyl-6,8-dioxa-3-thia-bicyclo(3,2,1)octane | − 4.1 | − 4 | − 3.6 | − 4.1 |

| 5_Methoxymethoxyhexa_2_3_diene | − 4.1 | − 3.4 | − 3.7 | − 4.2 |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | − 7.3 | − 5.9 | − 7.3 | − 6.4 |

| beta.-D-Ribopyranoside, methyl 2, 3,4-tri-O-methyl- | − 4.2 | − 4.1 | − 3.8 | − 4.2 |

| Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | − 4.3 | − 3.9 | − 4.3 | − 4.2 |

| Chloroacetic acid | − 3 | − 3.1 | − 3 | − 3.9 |

| Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylet hyl ester | − 5.1 | − 4.4 | − 4.8 | − 5.2 |

| Chloromethyl octyl ether | − 4.6 | − 3.7 | − 4.1 | − 4.5 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | − 5.7 | − 4.9 | − 5.4 | − 5.1 |

| Cyclohexanol_ 2_(2_propynyloxy)__ trans_ | − 5.2 | − 4.4 | − 5.1 | − 4.7 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | − 5.3 | − 4.6 | − 4.7 | − 6 |

| Dodecanoic acid | − 6.4 | − 4.8 | − 5.6 | − 6 |

| Ethyl Acetate | − 3.7 | − 3.3 | − 2.8 | − 3.8 |

| Ethylbenzene | − 6.1 | − 4.4 | − 4.5 | − 5.5 |

| Furo[′,3′:4,5]thiazolo[3,2-g]purine-8-methanol, 4-amino-6.alpha.,7,8,9a-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-, [6aS(6a.alpha.,7.alpha.,8.beta.,9a.alpha.)]- | − 6 | − 6.1 | − 5.4 | − 6.4 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-, methyl ester | − 6.5 | − 5.5 | − 5.8 | − 6.1 |

| Methyl 6_O_[1_methylpropyl]__beta_ _d_galactopyranoside | − 5.6 | − 5.7 | − 5.6 | − 5.7 |

| n-Butyl ether | − 4 | − 3.6 | − 3.8 | − 3.7 |

| n-Decanoic acid | − 5.9 | − 5 | − 5.5 | − 5.4 |

| N1,N1-Dimethyl-N2-(1-phenyl–ethyl) -ethane-1,2-diamine | − 6.3 | − 5.6 | − 5.5 | − 5.7 |

| Nonanoic acid | − 5.5 | − 4.8 | − 5.2 | − 5 |

| o-Xylene | − 6.4 | − 4.6 | − 4.5 | − 5.7 |

| Propanoic acid | − 3.6 | − 3.2 | − 3.1 | − 4.1 |

| Thioctic acid | − 5.3 | − 4.6 | − 4.9 | − 5 |

| Undec-10-ynoic acid | − 5.6 | − 4.9 | − 5.5 | − 5.5 |

Table 8.

Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemicals of Corchorus olitorius against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| 1,1-Cyclohexanedicarbonitrile | − 5.1 | − 5.1 | − 4.6 | − 5.4 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | − 4.8 | − 4.6 | − 4.7 | − 4.8 |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | − 3.6 | − 3.3 | − 3 | − 3.9 |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | − 3.6 | − 3.1 | − 3.2 | − 3.5 |

| 11-Bromoundecanoic acid | − 6 | − 4.9 | − 5.4 | − 5.6 |

| 12, 12-Dimethoxydodecanoic acid, methyl ester | − 5.1 | − 4 | − 4.5 | − 4.4 |

| 2-Ethylacridine | − 7 | − 6.4 | − 6.9 | − 7.1 |

| 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | − 4.7 | − 3.8 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | − 3.1 | − 3.3 | − 2.9 | − 3.1 |

| 2-Propenal | − 2.9 | − 2.6 | − 2.4 | − 3.2 |

| 3_4_dihydroxy_1_Butyl | − 3.8 | − 4 | − 3.4 | − 4.1 |

| 3-Phenylpropionic acid, 4-methoxy- 2-methylbutyl ester | − 5.7 | − 4.9 | − 5.7 | − 6.1 |

| 4-Ethyl-4-methyl-5-methylene-[1,3] dioxolan-2-one | − 4.8 | − 4.4 | − 4.1 | − 5 |

| 9-Bromononanoic acid | − 5.5 | − 4.4 | − 5.3 | − 5.9 |

| Acetamide, N-(4-hydroxycyclohexyl) -, cis- | − 5.6 | − 4.8 | − 5 | − 4.9 |

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl- | − 4.9 | − 4.3 | − 5 | − 5.1 |

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl-2-[(2-furanylmethyl)thio]- | − 5.9 | − 5.2 | − 5.5 | − 5.8 |

| Acetic acid_ butyl ester | − 3.8 | − 3.4 | − 3.5 | − 4.2 |

| Acetic acid_ pentyl ester | − 4.1 | − 3.6 | − 3.9 | − 4.6 |

| Benzene, 1,3-dimethyl- | − 6.2 | − 4.7 | − 4.8 | − 5.6 |

| Butane, 1, 1-dibutoxy- | − 4.7 | − 4 | − 4.2 | − 4 |

| Butyric acid, 2,2-dimethyl-vinyl ester | − 4.2 | − 4.2 | − 4 | − 4.8 |

| ethyl Acetate | − 3.1 | − 2.9 | − 2.8 | − 3.7 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester | − 4 | − 3.9 | − 3.8 | − 4.3 |

| Hexadecane, 1, 1- dimethoxy- | − 4.8 | − 3.8 | − 4.5 | − 4.5 |

| Isopropyl isothiocyanate | − 3.3 | − 3.4 | − 3.1 | − 3.6 |

| L-Lyxose | − 4.3 | − 4.9 | − 4 | |

| n-Butyl ether | − 3.8 | − 3.6 | − 3.9 | − 3.6 |

| N-Cyclododecylacetamide | − 6.3 | − 6 | − 5.8 | − 6.3 |

| o-Xylene | − 5.2 | − 4.6 | − 4.8 | − 5.6 |

| Octadecanoic acid | − 7 | − 5.7 | − 4.5 | − 6.9 |

| pyrrolidine_ 2_5_dione | − 4.4 | − 4 | − 5.9 | − 4.7 |

| Tridecyl (E)_2_methylbut_2_enoate | − 4.5 | − 3.9 | − 3.9 | − 4.8 |

Table 9.

Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemicals of Cassia alata against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| 1,3,3-Trimethyl-1-(4′-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyindane | − 6.9 | − 6.3 | − 7.2 | − 7.8 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | − 4.6 | − 4.2 | − 4.5 | − 4.4 |

| 1-Oxa-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-4-oxyl, 3,3-dimethyl-8-oxo- | − 5.5 | − 5.2 | − 5.1 | − 5.6 |

| 2-Octanol, 8,8-dimethoxy-2,6-dimethyl- | − 5.4 | − 4.9 | − 5.2 | − 5.4 |

| 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | − 4.4 | − 3.8 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| 6-Methyl-2-oxo-4-(4-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-pyrim idine-5-carboxylic acid 2-methylsulfanyl-ethyl ester 2_methylsulfanyl_ethyl ester | − 7.1 | − 6.9 | − 7.5 | − 7.2 |

| Acetaldehyde, butylhydrazone | − 4.3 | − 3.6 | − 3.8 | − 4.5 |

| Acetic acid, butyl ester | − 4.2 | − 3.4 | − 3.6 | − 4.2 |

| Butane, 1, 1-dibutoxy- | − 4.5 | − 3.9 | − 4.3 | − 4.3 |

| Butyric acid, 2, 2-dimethyl-, vinyl ester | − 4.2 | − 4.2 | − 4 | − 4.4 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | − 5.6 | − 4.9 | − 5.4 | − 5.8 |

| Cyclohexaneacetic acid, butyl ester | − 5.2 | − 4.1 | − 5.2 | − 5.4 |

| Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | − 7.6 | − 5.6 | − 6.6 | − 6.3 |

| D-Arabinitol | − 4.4 | − 5.2 | − 4 | − 4.5 |

| Ethanol, 2-phenoxy-, propanoate | − 5.1 | − 4.5 | − 5.2 | − 5.6 |

|

Furo[2′,3′:4,5]thiazolo[3,2-g]purine-8-methanol, 4-amino-6.alpha.,7,8,9a-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-, [6aS-(6a.alpha.,7.alpha.,8.beta.,9a.alph a.)]- |

− 5.9 | − 6.1 | − 5.4 | − 6.4 |

| Hexyl 2-hydroxyethyl sulfide | − 4.6 | − 4.5 | − 4.4 | − 4.5 |

| n-Butyl ether | − 4.1 | − 3.5 | − 3.9 | − 3.6 |

| o-Xylene | − 5.3 | − 4.6 | − 4.5 | − 5.7 |

| Paramethadione | − 4.7 | − 4.5 | − 4.3 | − 4.9 |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4 | − 4.6 |

| Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(2-furfurylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | − 6.4 | − 6.9 | − 6.8 | − 6.5 |

| Ribitol | − 5 | − 5.2 | − 4.8 | − 5 |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | − 5.1 | − 4.2 | − 4.7 | − 5.4 |

Table 10.

Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemicals of Phyllanthus amarus against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| 1,3-Dioxane, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | − 4.2 | − 3.9 | − 4 | − 4.1 |

| 1, 3-Hexanediol, 2-ethyl- | − 4.8 | − 4.7 | − 4.5 | − 4.6 |

| 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-.beta.-D-erythro-hexopyranose | − 4.9 | − 4.5 | − 4.1 | − 4.8 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy_-butane | − 4.6 | − 4.4 | − 4.7 | − 4.6 |

| 1-Hexene, 3, 4-dimethyl- | − 4.7 | − 4.2 | − 4.1 | − 5 |

| 1-Undecene, 2-methyl- | − 5 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 | − 4.3 |

| 2,4-Dipropyl-5-ethyl-1,3-dioxane | − 5 | − 4.6 | − 4.7 | − 4.8 |

| 2_Methylvaleroyl chloride | − 4.3 | − 4.1 | − 3.8 | − 4.4 |

| 2H-Pyran-2-one, tetrahydro-5,6-dimethyl-, trans- | − 4.9 | − 4.2 | − 4.2 | − 5.4 |

| 3-Hexanone, 2-methyl- | − 4.4 | − 3.8 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| 6-Bromohexanoic acid, hexyl ester | − 5 | − 3.8 | − 4.7 | − 4.6 |

| Acetic acid, butyl ester | − 3.7 | − 3.3 | − 3.5 | − 4.2 |

| Butane, 1,1′-[ethylidenebis(oxy)]bis- | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4.2 | − 4.3 |

| Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | − 4.5 | − 3.8 | − 4.1 | − 4.1 |

| Butanoic acid, butyl ester | − 4 | − 3.7 | − 4.1 | − 4.2 |

| Butyric acid, 2,2-dimethyl-, vinylester | − 4.4 | − 4.2 | − 4 | − 4.5 |

| Cyclododecylamine | − 6 | − 5.2 | − 5.5 | − 6 |

| Decanoic acid, propyl ester | − 4.8 | − 4.1 | − 4.2 | − 4.4 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-ylester | − 4.1 | − 3.9 | − 3.8 | − 4.1 |

| n-Butyl ether | − 4 | − 3.6 | − 3.7 | − 3.7 |

| n-Butyl isobutyl sulfide | − 3.8 | − 3.5 | − 4 | − 3.9 |

| Neopentyl isothiocyanate | − 4.3 | − 3.8 | − 3.7 | − 3.8 |

| o-Xylene | − 6.4 | − 4.6 | − 4.5 | − 5.6 |

| Pentane, 1-bromo-3,4-dimethyl- | − 4.3 | − 4.1 | − 4 | − 4.7 |

| Pentane, 2,3-dimethyl- | − 4.4 | − 3.7 | − 3.8 | − 4.8 |

| Propane, 1-isothiocyanato- | − 3.4 | − 3.2 | − 3.2 | − 3.3 |

Table 11.

Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemicals of Vernonia amygdalina against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| (4-Methoxymethoxy-hex-5-ynylidene)-cyclohexane | − 5.5 | − 4.6 | − 5.4 | − 5.3 |

| .beta.-D-Xylopyranoside, methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-methyl- | − 3.8 | − 4 | − 3.8 | − 4.5 |

| 1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanamine | − 4.9 | − 4.7 | − 4.7 | − 4.6 |

| 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-.beta.-D-erythro-hexopyranose | − 4.9 | − 4.5 | − 4.1 | − 4.7 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | − 4.3 | − 3.9 | − 4.7 | − 4.6 |

| 1-Butyl-3,4-dihydroxy-pyrrolidine- 2,5-dione | − 5.3 | − 5.1 | − 4.8 | − 6.2 |

| 1-Hexene, 3,4-dimethyl- | − 4.7 | − 4.2 | − 4.1 | − 5 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | − 5.3 | − 4.9 | − 5 | − 5.7 |

| 1_Propanol_ 2_2_dimethyl__ acetate | − 4.1 | − 3.8 | − 3.8 | − 4.3 |

| 2-Butenoic acid, butyl ester | − 4.3 | − 3.7 | − 3.9 | − 4 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | − 4.1 | − 3.5 | − 3.8 | − 4.7 |

| 2-Propanone, propylhydrazone | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4.1 | − 4.2 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | − 3.1 | − 3 | − 2.9 | − 3.4 |

| 2-Propenal | − 3 | − 2.6 | − 2.4 | − 3.2 |

| 2-Tetradecanol | − 6.4 | − 5.1 | − 5.9 | − 6.1 |

| 2H-1,2,3-Triazol-4-amine, 2-cyclohexyl-5-nitro-, 1-oxide | − 6.4 | − 5.6 | − 5.9 | − 6.6 |

| 3,4,5-Trimethyldihydrofuran-2-one | − 4.5 | − 4.2 | − 4.1 | − 5.1 |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | − 4.7 | − 4.5 | − 4.4 | − 5.1 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | − 5.8 | − 5.3 | − 5.2 | − 5.9 |

| 8-Chlorocapric acid | − 5.7 | − 5.1 | − 5.3 | − 5.3 |

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl- | − 5.3 | − 4.3 | − 5 | − 5 |

| Acetamide, N-cyclohexyl-2-[(2-furanylmethyl)thio]- | − 5.9 | − 5.6 | − 5.4 | − 6 |

| Acetic acid, butyl ester | − 3.7 | − 3.2 | − 3.5 | − 4 |

| Aziridine, 2-methyl- | − 3.3 | − 2.6 | − 2.7 | − 3.3 |

| Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4.1 | − 4.1 |

|

Carbamic acid, [1-(hydroxymethyl)-2-phenylethyl]-, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester, (s)- |

− 6.1 | − 6.2 | − 5.7 | − 6.6 |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | − 4.3 | − 4 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| Cyclohexane acetic acid, butyleste | − 5.4 | − 4.4 | − 5.2 | − 4.8 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | − 5.2 | − 4.9 | − 5.4 | − 5.1 |

| Cyclohexaneacetic acid_ butyl ester | − 5.6 | − 4.6 | − 5.2 | − 5.1 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(1-mercapto-1-methylethyl)-5-methyl-, trans- | − 5.2 | − 5.3 | − 5.1 | − 5.7 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | − 5.1 | − 4.5 | − 4.7 | − 5.4 |

| Cyclopentane, 1-methyl-2-(4-methylpentyl)-, trans- | − 5.4 | − 4.8 | − 5.1 | − 5.5 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | − 5.2 | − 4.8 | − 5.1 | − 5.3 |

| Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | − 7.7 | − 5.9 | − 6.8 | − 6.3 |

| Dodecanoic acid | − 6.5 | − 5.1 | − 5.4 | − 5.3 |

| Ethanamine, N-pentylidene- | − 3.9 | − 3.3 | − 3.8 | − 3.6 |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | − 3.5 | − 3.3 | − 3 | − 3.8 |

| Ethanol, 2-bromo- | − 2.9 | − 2.9 | − 2.7 | − 3.3 |

| Ethyl Acetate | − 3.5 | − 3 | − 2.9 | − 3.9 |

| Ethylbenzene | − 6.1 | − 4.4 | − 4.5 | − 5.5 |

|

Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester |

− 4.1 | − 3.9 | − 3.8 | − 4.2 |

| Morpholine | − 3.2 | − 3.3 | − 3 | − 4.2 |

| n-Butyl ether | − 4.1 | − 3 | − 3.7 | − 4.5 |

| N-Cyclododecylacetamide | − 6.4 | − 6 | − 5.8 | − 6.4 |

| n-Decanoic acid | − 6.1 | − 4.9 | − 5.6 | − 5.9 |

| Oxirane, (1-methylethyl)- | − 3.5 | − 3.2 | − 4.8 | − 3.7 |

| Oxonin, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-, (Z,Z)32 | − 4.9 | − 4.6 | − 3.3 | − 5.4 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | − 6.8 | − 5.3 | − 4.3 | − 6.2 |

| Pentane, 1-bromo-3,4-dimethyl- | − 4.3 | − 4.1 | − 5.9 | − 4.7 |

| Propane, 1,2-dichloro-2-fluoro- | − 3.7 | − 3.6 | − 4 | − 3.7 |

| Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(5-hydroxymethylfurfur-2-ylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | − 6.7 | − 6.7 | − 3.6 | − 6.3 |

| Succinic acid, hexyl 3-oxobut-2-yl-ester | − 4.7 | − 4.1 | − 6.7 | − 5.5 |

| Thiazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | − 3.7 | − 3.2 | − 4.8 | − 3.7 |

| Tridecyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | − 5.5 | − 4.3 | − 3.3 | − 5.1 |

Table 12.

Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemicals of Anacardium occidentale against proteins of Coronavirus-2

| Phytochemicals | 2AJF | 6LU7 | 6VXS | 7BTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | Binding energies (kcal/mol) | |

| .alpha.-D-Glucopyranose, 4-O-.beta.-D-galactopyranosyl | − 6.3 | − 6.4 | − 6.3 | − 6.2 |

| 1-Benzenesulfonyl-1H-pyrrole | − 6.7 | − 5.6 | − 5.6 | − 6 |

| 1-Butoxy-1-isobutoxy-butane | − 4.6 | − 4.1 | − 4.6 | − 4.4 |

| 1-Methoxy-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)nonane | − 5.7 | − 4.8 | − 5 | − 5.6 |

| 1-Octene, 2-methyl- | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4.1 | − 4.6 |

| 1-Oxa-4-azaspiro[4.5]decan-4-oxyl, 3,3-dimethyl-8-oxo- | − 5.1 | − 5.3 | − 5.2 | − 6 |

| 1-Pentadecene, 2-methyl- | − 5.6 | − 3.8 | − 4.6 | − 4.8 |

| 1-Pentene, 5-chloro-4-(chloromethyl)-2,4-dimethyl- | − 4.9 | − 4 | − 4.2 | − 4.7 |

| 1-Phenyloxycarbonyl-7-pentyl-7-aza bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane | − 6.4 | − 6 | − 6.7 | − 6.2 |

| 1-Propanol,2,2-dimethyl- acetate | − 4 | − 3.9 | − 3.7 | − 4.3 |

| 1H-Imidazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | − 4.3 | − 3.6 | − 3.5 | − 4.6 |

| 1H-Indole, 5-methyl-2-phenyl- | − 6.9 | − 7.2 | − 7.4 | − 7.1 |

|

2(1H)-Naphthalenone, octahydro-4a- methyl-7-(1-methylethyl)-, (4a.alp ha.,7.beta.,8a.beta.) - |

− 6.2 | − 6 | − 6.2 | − 6.7 |

| 2-Butylthiazoline | − 4.1 | − 3.7 | − 3.7 | − 4 |

| 2-Butynamide, N-methyl- | − 4.1 | − 3.5 | − 3.8 | − 4.3 |

| 2-Propanone, propylhydrazone | − 4.2 | − 3.6 | − 4.1 | − 4.3 |

| 2-Propen-1-amine | − 3.4 | − 3 | − 2.9 | − 3.5 |

| 3-Oxatricyclo[4.2.0.0(2,4)]octan-7-one | − 4.7 | − 4.5 | − 4.4 | − 5.1 |

| 3H-Naphth[1,8a-b]oxiren-2(1aH)-one, hexahydro- | − 5.8 | − 5.3 | − 5.3 | − 6.1 |

| 4.beta.,5-Dimethyl-6,8-dioxa-3-thiabicyclo(3,2,1)octane 3-oxide | − 4.7 | − 4.6 | − 4.1 | − 4.7 |

| 4-t-Butylcyclohexylamine | − 5.6 | − 5.1 | − 5.3 | − 5.7 |

| Acetaldehyde, butylhydrazone | − 4.4 | − 3.8 | − 3.8 | − 4.2 |

| Acetamide, N-(4-hydroxycyclohexyl) -, cis- | − 5.6 | − 4.9 | − 5 | − 5.1 |

| Acetic acid, butyl ester | − 3.9 | − 3.4 | − 3.5 | − 3.8 |

| Butane, 1,1-dibutoxy- | − 4.2 | − 3.7 | − 4.3 | − 4 |

| Butane, 2,2′-thiobis- | − 4 | − 3.5 | − 3.8 | − 4.2 |

| Chloroacetic acid, 1-cyclopentylethyl ester | − 5.2 | − 4.5 | − 4.7 | − 5.2 |

| Cyclobutanone, 2-methyl-2-oxiranyl | − 4.3 | − 4.1 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 |

| Cyclododecanol, 1-aminomethyl- | − 6.1 | − 5.8 | − 6.1 | − 6.8 |

| Cyclohexane, 1R-acetamido-2,3-cis-epoxy-4-cis-formyloxy- | − 5.8 | − 4.9 | − 5.4 | − 5.3 |

| Cyclohexanone, 2-(2-propenyl)- | − 4.9 | − 4.4 | − 4.7 | − 5.9 |

| Cyclopentaneethanol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-.beta.,3-dimethyl- | − 5.2 | − 4.8 | − 5.1 | − 5.2 |

| Cyclopentaneundecanoic acid | − 7.3 | − 5.7 | − 6.6 | − 7.2 |

| Dimethylamine, N-(neopentyloxy)- | − 3.8 | − 3.7 | − 3.6 | − 4.2 |

| Dodecanoic acid, 1,2, 3-propanetriyl ester | − 5.5 | − 3.9 | − 4.5 | − 5 |

| Ethanamine, N-pentylidene- | − 3.8 | -3.3 | − 3.8 | − 4.6 |

| Ethane, 1-chloro-2-isocyanato- | − 3.4 | − 3 | − 3 | − 3.8 |

| Ethanol, 2-butoxy- | − 4.2 | − 3.6 | − 3.8 | − 4.1 |

| Ethyl Acetate | 3.3 | − 3.2 | − 2.8 | − 3.7 |

| Ethylbenzene | − 6.1 | − 4.4 | − 4.5 | − 5.5 |

| Formic acid, 3,3-dimethylbut-2-yl ester | − 3.9 | − 3.8 | − 3.8 | − 4.2 |

| n-Butyl ether | − 4 | − 3.4 | − 3.8 | − 3.8 |

| n-decanoic acid | − 5.8 | − 4.9 | − 5.6 | − 6 |

| Neopentyl isothiocyanate | − 3.8 | − 3.6 | − 3.7 | − 3.9 |

| Nonanoic acid | − 5.5 | − 4.8 | − 5 | − 5.2 |

| o-Xylene | − 5.2 | − 4.6 | − 4.5 | − 5.7 |

| p-Xylene | − 6.1 | − 4.5 | − 4.5 | − 5.6 |

| Pyrazol-3(2H)-one, 4-(5-hydroxymethylfurfur-2-ylidenamino)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl- | − 6.7 | − 6.7 | − 6.7 | − 6.6 |

| Pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine, 4-phenyl- | − 6.8 | − 6.3 | − 6.6 | − 7 |

| Spiro[2.3]hexan-4-one, 5,5-diethyl | − 4.6 | − 4.1 | − 4.5 | − 4.9 |

| Succinic acid,butyl decyl ester | − 5.4 | − 4.2 | − 4.7 | − 4.8 |

| Thiazole, 2-ethyl-4,5-dihydro- | − 3.4 | − 3.2 | − 3.3 | − 3.5 |

| Tridecanoic acid | − 6.5 | − 5.1 | − 6 | − 6 |

| Z,E-7,11-Hexadecadien-1-yl acetate | − 5.7 | − 4.5 | − 5 | − 5.2 |

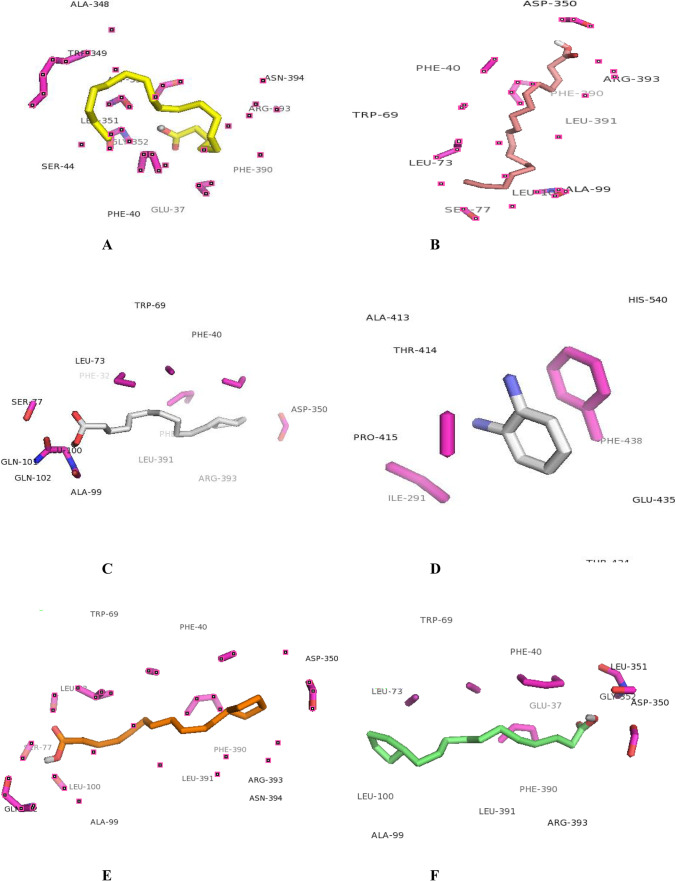

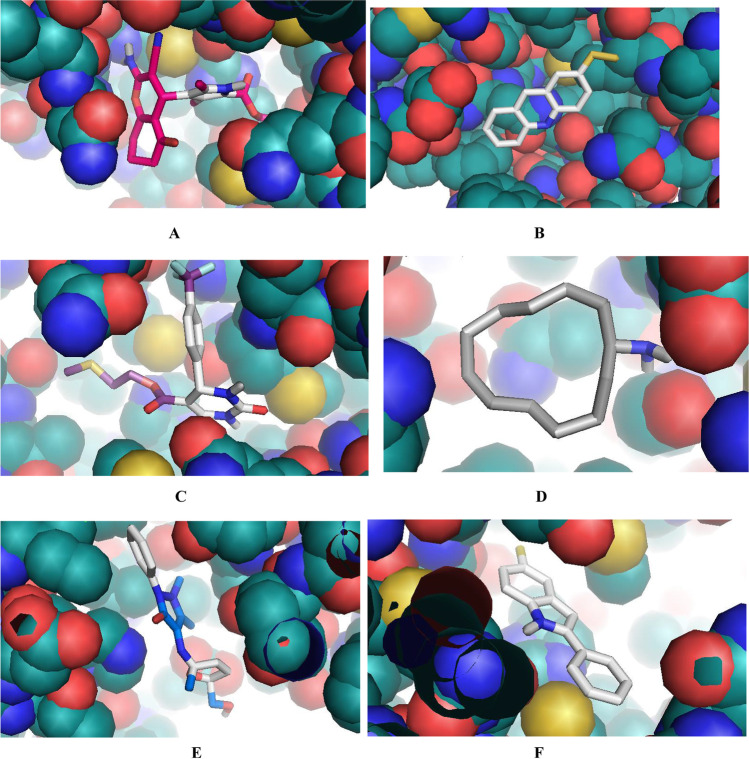

Molecular docking analysis of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain (2AJF)