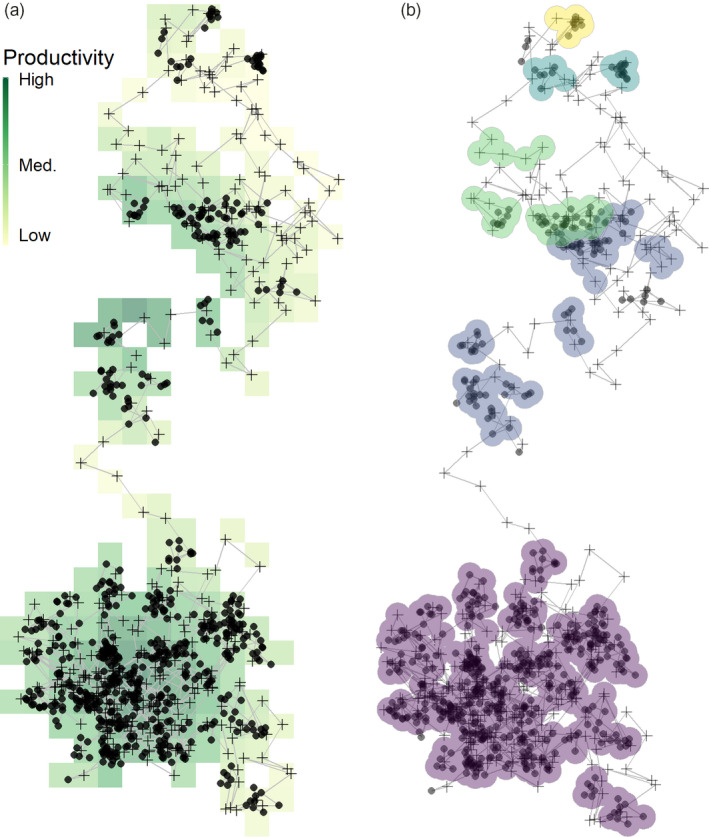

FIGURE 6.

Movement tracks can be classified into residence patches while leaving out the transit between them. (a) A simulated animal movement track from Gupte et al. (2021), where an agent uses local cues to make movement decisions to maximise intake. The agent tends to stop (solid circles) on high‐productivity areas of the landscape, as these are more likely to generate prey items. Transit points between stationary phases are shown as crosses. (b) Our simple, first‐principles‐based clustering algorithm classifies the track into five residence patches. Some transit points are erroneously classified as being part of a residence patch (top, yellow), illustrating why is it important to remove such data before applying this method. Simultaneously, some points where the animal is not stationary for long are not picked up by the method. While the large purple patch (bottom) is composed almost entirely of consecutive positions, the subsequent patches are composed of multiple parts. This is because our method was designed to be robust to missing data from empirical tracks; the spatial and temporal limits of splitting and lumping can be controlled using the arguments passed to atl_res_patch, and can be adjusted to fit the study system. Users are cautioned that there are no ‘correct’ options, and the best guide is the behavioural biology of the tracked individual