Abstract

This study introduces a database for analyzing COVID-19’s impacts on China’s regional economies. This database contains various sectoral and regional economic outcomes at the weekly and monthly level. In the context of a general equilibrium trade model, we first formulate a mathematical representation of the Chinese regional economy and calibrate the model with China’s multi-regional input-output table. We then utilize the monthly provincial and sectoral value-added and national trade series to estimate COVID-19’s province-by-month labor-productivity impacts from February 2020 to September 2020. As a year-on-year comparison, relative to February 2019 levels, we find an average 39.5% decrease in labor productivity (equivalent to around 305 million jobs) and an average 25.9% decrease in welfare. Labor productivity and welfare quickly returned to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020. By September 2020, relative to September 2019, average labor productivity increased by 12.2% (equivalent to around 94 million jobs) and average welfare increased by 8.2%.

JEL: J01, E20, F10, R13

Highlights

We quantify COVID-19’s province-by-month labor productivity and welfare impacts on China’s economies.

The analysis is based on a new database and a computable general equilibrium (CGE) modeling approach.

Labor productivity declined by 39.5% in February 2020 but quickly recovered since April 2020.

The recovery patterns are heterogeneous across regions.

Introduction

In late 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic started in Hubei, China. The pandemic quickly spread to other countries over the first several months of 2020 causing significant global economic and social costs. According to the International Monetary Fund, global gross domestic product (GDP) decreased by 3.5% in 2020 compared to 2019, with a decrease of 4.9% for advanced economies and a decrease of 2.4% for emerging markets and developing economies. China was the only major economy reporting an economic expansion, with a growth rate of 2.3% (IMF 2021). During the early stages of the pandemic, China took strict lockdown and quarantine measures, then gradually loosened mobility restrictions and resumed economic activities in late March (Fang et al. 2020). China’s negative year-on-year GDP growth rate of −6.8% in the first quarter of 2020 reflects the significant economic costs associated with the stagnation of economic activities. According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS), since April 2020, China’s economy has gradually recovered with year-on-year GDP growth rates of 3.2%, 4.9%, and 6.5% in the second, third, and fourth quarters of 2020, respectively (CNBS 2020). The spread of COVID-19 in other economies also significantly affected China’s economy via trade links formed during the past decades of globalization. In the first quarter of 2020, while China’s goods export value fell by 11.4% compared with the first quarter of 2019, year-on-year exports increased by 4.5%, 10.2%, and 4.0% in the second, third, and fourth quarters, respectively. The export growth reflects both China’s productivity recovery and other countries’ production and distribution capabilities contraction, which helped create favorable conditions for China’s exports.

National economic outcomes, however, cannot capture the uneven impacts of COVID-19 across China’s regions and sectors. This heterogeneity is not only rooted in the regional disparities in economic development levels and reliance on exports, but also caused by COVID-19’s spatial propagation patterns and the varying stringency of control measures across China. Understanding how COVID-19 affects China’s regional economies is important for designing and evaluating relevant economic recovery policies. While CNBS publishes the value-added growth rate of sectors and provinces on a monthly basis, it does not publish province-level labor statistics on a monthly basis. Due to the complex input-output linkages across sectors and provinces, regional and sectoral labor productivity changes affect regional and sectoral value-added via the production networks reflected by the multi-regional input-output (MRIO) table. Given that regional labor estimates are an important basis of regional recovery and support strategies, we aim to quantify the implied monthly regional labor productivity and welfare impacts embedded in the value-added statistics. Our estimates are useful to policy makers because they can be used to translate COVID-19 responses into familiar metrics for assessing economic costs — job equivalents and money-metric welfare (equivalent variation).

We first introduce a subnational database, the CARD COVID-19 Economic Database: China, developed by the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development (CARD) at Iowa State University, which contains various regional and sectoral economic outcomes (He et al. 2020). Researchers can use the database to assess COVID-19’s impacts on China’s national and subnational economy. We then use a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model that accounts for extensive sectoral and regional economic linkages in China to quantify the regional implied labor productivity shocks that best fit the observed changes in monthly provincial and sectoral value-added and national trade series. Specifically, we use a comparative static model calibrated to a 30 provinces by 30 sectors MRIO table developed by Mi et al. (2018).1 This MRIO table provides inter-provincial and inter-sectoral economic flows among 30 economic sectors in China’s 30 provinces in 2012. This is the first MRIO table to reflect China’s economic development pattern after the 2008 global financial crisis (Mi et al. 2018). The MRIO table accounts for complicated input-output linkages between sectors across provinces and can capture the production network and key technology differences across geography.

We use the structural model to quantify the implied monthly provincial labor productivity and welfare impacts that are consistent with observed provincial and sectoral output changes.2 We run the model with and without incorporating shocks that target observed national imports and exports. This yields two sets of implied labor productivity and welfare estimates.3 While the structural model does not distinguish between provincial labor productivity or employment shocks, we can use information on wage bills to back out a jobs equivalent. The comparison of the results with and without trade targeting provides insights on how global pandemic responses impact China’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our main results show that in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic had substantial yet short-lived impacts on labor productivity across Chinese provinces, especially in the epicenter, Hubei Province. Across provinces, when we do not consider trade shocks, average year-on-year labor productivity fell by 37.9% and average welfare fell by 20.8% in February 2020. The 37.9% decrease in labor productivity is equal to 293 million jobs based on an employment of 774 million in 2019. In Hubei, year-on-year labor productivity fell by 74.1% (26.3 million job equivalent) in February 2020. Our estimated productivity shocks are for the aggregate provincial labor force and do not differentiate losses of employment, reductions in working hours, or other sources of productivity adjustments. We report these as losses in the productive capacity of the labor force or as full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs, which is a useful and familiar metric for assessing labor market shocks.

Labor productivity and welfare recovered quickly in 2020. By September 2020, relative to September 2019, average labor productivity increased by 29.8% (230 million job equivalent) and average welfare increased by 14.7% across all provinces. This year-on-year productivity growth is high even for a fast growing country like China. This prediction moderates substantially when we consider COVID-19 related trade shocks, as described below. Focusing on Hubei Province, the year-on-year labor productivity increase is 19.4% (6.9 million job equivalent) as of September 2020. In addition, we find significantly heterogeneous recovery patterns across regions. Specifically, provinces in eastern China recovered the fastest, from a population-weighted average year-on-year labor-productivity shock of −45.1% in February to +39.2% in September 2020. The labor productivity recovery in northwestern China is more modest and increased from a negative shock of −23.3% in February to +23.3% in September 2020. These estimates rely on endogenous trade responses native to the model formulation of China as a large open economy. We postulate, however, in a set of follow-up estimates that COVID-19 included substantial shifts in China’s export-demand and import-supply schedules. We guide these trade shocks using observed changes in aggregate imports and exports.

The patterns of the pandemic’s spatial and temporal impacts on labor productivity are similar across treatments, with and without trade shocks, but there are some important differences to highlight. Labor productivity estimates grew faster in April-June and grew slower in August and September 2020 when we consider national trade shocks. Specifically, with trade shocks included, a year-on-year comparison for February indicates an average 39.5% decrease in labor productivity (equivalent to around 305 million jobs) and an average 25.9% decrease in welfare. These are only slightly larger than when we do not include trade shocks, but the trade shocks become more important in the recovery period. For September 2020, relative to September 2019, average labor productivity increased by 12.2% (equivalent to around 94 million jobs) and average welfare increased by 8.2%. These are much lower than the estimates under no trade shocks. An explanation for this difference is that China’s net-export demand increased significanlty after July. To accommodate the observed income growth accounting for the trade shocks means that less burden is placed on productivity. Therefore, the models without national trade shocks slightly underestimates the labor productivity shocks from April-June, but substantially overestimates the labor productivity increases in August and September.

This study relates to and contributes to three strands of literature. First, this paper contributes to a line of literature that uses general equilibrium models to investigate COVID-19’s impacts in different countries, including the United States (Walmsley et al. 2021), China (Zhao 2020), the UK (Keogh-Brown et al. 2020), India (Sahoo and Ashwani 2020), and Brazil (Porsse et al. 2020). The unique contribution of this paper is that we conduct the analysis at the province level and we are able to quantify the labor productivity impacts at the province-by-month level, while most studies are at the national and annual level (Keogh-Brown et al. 2020; Maliszewska et al. 2020; McKibbin and Fernando 2020; Sahoo and Ashwani 2020; Zhang et al. 2020; Zhao 2020). For example, Maliszewska et al. (2020) simulate the impacts of a global pandemic using Envisage (a well documented CGE model) calibrated to GTAP 10 accounts and find global GDP decreased by 2.0% in a full global pandemic and decreased by 4.0% in an amplified global pandemic. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2020) utilize an economy-wide multi-sector multiplier model built on China’s 2017 social accounting matrix with 147 economic sectors to assess COVID-19’s impacts on China’s macroeconomy and find that China’s economy will grow less than 1.0% in 2020 without resumed export demand and 1.7% with resumed export demand. Notable exceptions that use subnational CGE models to investigate COVID-19’s impacts are Porsse et al. (2020) and Modrego et al. (2020). Porsse et al. (2020) use a dynamic inter-regional CGE model to project COVID-19’s economic impacts in Brazil. Modrego et al. (2020) estimate COVID-19’s regional employment effects across Chile’s regions. Considering COVID-19’s impacts could be quite heterogenous across subnational regions and the paucity of regional data suitable for CGE modeling has long been a constraint (Giesecke and Madden 2013), the subnational labor productivity estimates provided in this paper are important to inform regional recovery and support strategies.

Second, this paper introduces two complete datasets of COVID-19’s estimated impacts on China’s province-by-month labor productivity. These estimates are useful for future academic and health-policy analysis. In this way, this paper contributes to the broader literature on COVID-19’s impacts on regional employment and economic outcomes (Bartik et al. 2020; Barwick et al. 2020; Bottan et al. 2020; Forsythe et al. 2020). Barwick et al. (2020) use mobile phone records for 71 million users and a difference-in-differences (DID) framework to study the COVID-19 pandemic’s labor market impacts in Guangdong, China and find that the pandemic increased unemployment by 27%–62% from late January to the end of September 2020. Reduced-form analysis is the basis of most studies on COVID-19’s labor market impacts, which could neglect the feedback effects by broader supply and demand factors. Our paper contributes by utilizing a CGE modeling framework that accounts for broad linkage between regions and sectors.

Third, while researchers often use CGE models to simulate the impact of actual or hypothetical policies (Giesecke and Madden 2013), we use our model to uncover unobserved implied shocks that are consistent with observables as in Bauer et al. (2005) and Monte et al. (2018). Specifically, Monte et al. (2018) use a general equilibrium model to recover unique values of the unobserved productivity and amenities fundamentals that rationalize observed wages, employment, commuting flows, and land area. Dixon and Rimmer (1998) and Dixon and Rimmer (2002) also apply similar methods for accurate forecasting and policy analysis in the context of a dynamic model of Australia. We contribute to the CGE modeling literature by providing an example of utilizing observed output and trade data to uncover unobserved labor productivity shocks. This is especially useful when subnational labor statistics are not collected or reported in a timely manner. Considering some important regional labor statistics are often non-existent or outdated in developing countries, future studies can follow this method and use observed output and trade data to back out labor statistics not reported in a timely manner.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section two offers a description of the database and the value-added and trade data used in the analysis. Section three describes the general equilibrium modeling structure. Section four presents the labor productivity and welfare estimates. Section five discusses the limitations of the model and potential future extensions.

Data

CARD COVID-19 Economic Database: China

He et al. (2020) developed the CARD COVID-19 Economic Database: China to track COVID-19’s evolving impacts on China’s regional economy and to facilitate research on COVID-19’s global impact via economic linkages between China and the rest of the world. This database was first released in April 2020 and updated monthly through September 2020.4 There are 45 tables in the database. Table 1 describes the main data categories in the database: sectoral level data using China’s IO (input-output) classification;5 sectoral level data using GTAP classification; provincial data; province-by-IO sectoral data; province-by-GTAP sectoral data; provincial and sectoral GDP; monthly agricultural trade; timing of prevention and control measures; and raw datasets. We collect these data from various sources, including, but not limited to, CNBS, various provincial bureaus of statistics, China’s Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affairs, the Global Agricultural Trade System at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and USDA’s weekly agricultural export query system. We update the data on a quarterly, monthly, bi-weekly, or weekly basis.

Table 1.

Data categories in CARD COVID-19 Economic Database: China

| Number | Category | Classification | Variables | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–4 | Sectoral data | China IO | Value-added growth rate (manufacturing sectors only); Fixed capital investment growth rate | Monthly |

| GTAP | Same as above | Monthly | ||

| 5–9 | Provincial data | N/A | Value-added growth rate (manufacturing sectors only); Fixed capital investment growth rate; Baidu Huiyan Provincial Resumption Index; Firm and labor resumption data (for enterprises above a designated size) | Monthly, weekly, bi-weekly |

| 10–13 | Province-by-sector data | China IO | Value-added growth rate (manufacturing sectors only); Fixed capital investment growth rate | Monthly |

| GTAP | Same as above | Monthly | ||

| 14–18 | Concordance and sector classifications | N/A | Concordance between IO, GB, and GTAP sectors | N/A |

| 19–35 | Raw datasets | Various datasets used to generate the database | Quarterly, monthly, weekly, bi-weekly | |

| 36–37 | Industry and provincial GDP | Quarterly cumulative GDP (100 million RMB), Provincial cumulative GDP (100 million RMB) | Quarterly | |

| 38–43 | Agricultural trade | China’s monthly agricultural import/export quantity/value; U.S. monthly agricultural exports to China; U.S. weekly key agricultural commodities exports to China | Monthly | |

| 44 | Timing of prevention and control measures | Levels of prevention and control measures in different cities | ||

| 45 | Aggregate trade shocks | National-level growth rate of total imports and exports | Monthly |

Note: This table presents the main data categories in CARD COVID-19 Economic Database: China available at https://www.card.iastate.edu/china/covid-19/. The number denotes the order of tables in the database.

Given the necessity of converting the sectoral GB (Guobiao) data into IO or GTAP sectoral data that we can use in GTAP and regional equilibrium modeling, He et al. (2020) develops crosswalks between GB and IO, and GB and GTAP sectors.6He et al. (2020) also obtain the IO and sectoral GTAP data by concording the GB sectoral data reported by CNBS with the crosswalks between different classifications. The main sectoral and provincial outcomes are the monthly growth rate of value-added and fixed capital investment.7 In addition to monthly data in 2020, He et al. (2020) collect data in November and December 2019 as reference points.

Provincial and sectoral value-added growth rate and national trade shocks

The outcomes utilized in the CGE modeling are province- and sector-by-month growth rate of value-added and trade flows from Tables 1, 4, and 45 in the CARD database. While some datasets track labor shocks, like the Baidu resumption index based on mobile phone usage, there are no systematic labor productivity shocks available. We are interested in the implied labor productivity shocks and welfare impacts reflected by the observed output growth rate and trade flows. Therefore, we use the monthly growth rate of provincial and sectoral value-added and national export and import data from November 2019 to September 2020 as output targets in the CGE modeling.

Table 2 presents the year-on-year growth rate of value-added in five typical provinces—Beijing, Hubei, Zhejiang, Xinjiang, and Heilongjiang—and six administrative regions, as well as the national growth rate of export and import values.8 We select these five provinces because of their differing COVID-19 outbreak timing and lockdown measures as well as heterogeneity in economic reliance on manufacturing and trade. All five provinces are representative of the recovery in China’s different regions. Figure 8 in the Appendix shows China’s provinces and regions. Table 2 shows Hubei’s year-on-year value-added reduced by 46.2% and 46.9% in February and March 2020, respectively, compared to 2019 levels. In February, Xinjiang’s value-added reduced 0.7%; however, it recovered in March 2020. Across regions, provinces in south-central China, where Hubei is located, experienced the largest drop in value-added, while provinces in northwestern China were least affected in terms of value-added. This geographical pattern is consistent with the spread of COVID-19 in China—the pandemic affected Hubei first and most and affected northwestern provinces the least.

Table 2.

Observed year-on-year monthly growth rate of provincial value-added and national trade flows (%)

| Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Growth rate of value-added (%) | ||||||||||

| Beijing (BJ) | 2.5 | 4.8 | −16.2 | −13.0 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 5.9 | 5.4 |

| Hubei (HB) | 6.2 | 7.8 | −46.2 | −46.9 | −2.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 6.2 |

| Heilongjiang (HL) | −1.6 | 7.7 | −10.9 | −5.5 | 2.9 | 0.3 | −0.5 | −1.9 | 8.5 | 9.0 |

| Zhejiang (ZJ) | 9.0 | 9.8 | −18.5 | 1.3 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 9.9 | 10.7 |

| Xinjiang (XJ) | 2.8 | 1.6 | −0.7 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 9.6 | 12.2 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 11.2 |

| North (5 provinces) | 3.8 | 3.8 | −11.6 | −3.4 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 7.1 | 6.4 |

| Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, inner Mongolia | ||||||||||

| Northeast (3 provinces) | 6.8 | 10.3 | −13.5 | −6.1 | 3.1 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 3.6 | 11.6 | 7.9 |

| Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang | ||||||||||

| East (7 provinces) | 7.0 | 8.4 | −15.3 | 1.8 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 7.5 |

| Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong | ||||||||||

| South-central (6 provinces) | 7.2 | 7.5 | −18.9 | −8.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

| Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guandong, Guangxi, Hainan | ||||||||||

| Southwest (4 provinces) | 3.4 | 5.3 | −13.5 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan | ||||||||||

| Northwest (5 provinces) | 7.7 | 8.9 | −4.4 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 6.1 |

| Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang | ||||||||||

| Panel B: Growth rate of trade value (%) | ||||||||||

| Imports | 0.8 | 16.5 | −4.0 | −1.0 | −14.2 | −16.7 | 2.7 | −1.4 | −2.1 | 13.2 |

| Exports | −1.3 | 7.9 | −17.2 | −6.6 | 3.5 | −3.3 | 0.5 | 7.2 | 9.5 | 9.9 |

This table shows year-on-year value-added growth rate in five provinces and six regions and China’s national trade value growth rate. Average growth rate in each region is the simple average of growth rate in all provinces in that region.

Fig. 8.

China’s provinces and regional classifications

In 2020, China’s exports also suffered severe reductions of 17.2% in February and 6.6% in March. However, exports have significantly increased since June, and reached a year-on-year growth rate of 9.9% in September. The large export increase since June was partially caused by China’s production increase and other countries’ constrained supply capacities as they were gradually affected by the pandemic (IMF 2021). While China’s imports in 2020 fell by only 4.0% and 1.0% in February and March compared with their levels in the same month in 2019, respectively, they fell sharply by 14.2% and 16.7% in April and May compared with their levels in the same month in 2019, and gradually returned to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020.

Figure 1 shows the COVID-19 pandemic’s shocks on year-on-year value-added growth rates of selected sectors. The average value-added across all sectors decreased by 18.4% in February and gradually returned to a growth rate of 5.0% in September 2020. WAP (Clothing, leather, fur, etc.) grew slowest while EEQ (Electrical–Electronic equipment) grew fastest. Given that WAP closely relates to TEX (Textile) and TEX grew faster than WAP, we modify the value-added growth rate of WAP with the combination of average growth rate across all sectors and the growth rate of TEX. Similarly, given EEQ closely relates to TEQ (Transportation sector), we modify the value-added growth rate of EEQ with the combination of average growth rate across all sectors and the growth rate of TEQ. Table 3 presents the actual sectoral shocks we use in our modeling. For WAP and EEQ, the values in bold are the actual shocks used, and values in brackets are the raw data in the CARD database. Note that for several sectoral shocks, we cannot find a reasonable value and omit them in the modeling (labeled as -"—” in Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Value-added growth rate of China’s manufacturing sectors. Note: See Table 3 for sector descriptions. We only include manufacturing sectors. Based on authors' compilation from China's National Bureau of Statistics and concordance between IO sectors and industrial sectors in the industrial classification for national economic activities in GB/T 4754-2011

Table 3.

Observed year-on-year monthly value-added growth rate of China’s manufacturing sectors (%)

| Sectors | Abbr. | Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Coal mining | COL | 7.2 | 9.2 | −8.2 | 9.1 | 3.7 | 0.3 | −0.3 | −4.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| 3. Petroleum and gas | CRU | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.1 | −1.3 | −6.2 | 3.4 | 8.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| 4/5. Metal mining - Nonmetal mining | OXT | 1.2 | 6.5 | −25.5 | −6.3 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 2.5 | −0.3 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| 6. Food processing and tobaccos | FOO | −0.9 | 4.8 | −12.7 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.03 | −1.3 | 3.8 |

| 7. Textile | TEX | 2.5 | 0.2 | −20.0 | −5.5 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 5.6 |

| 8. Clothing, leather, fur, etc. | WAP | 2.5a | –a | −12.9a | −3.1a | −7.4 | −8.2 | –a | –a | 3.7a | 5.6a |

| (0.7) | (−0.8) | (−28.7) | (−9.5) | (−10.7) | (−11.6) | (−10) | (−6.3) | ||||

| 9. Wood processing and furnishing | LUM | 2.6 | 3.8 | −26.0 | −4.7 | −3.2 | −3.6 | −4.9 | −2.6 | −0.5 | 2.5 |

| 10. Paper making, printing, stationery, etc. | PPP | 2.0 | 1.7 | −25.7 | −4.7 | 1.0 | −2.1 | −3.1 | −1.4 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

| 11. Petroleum refining, coking, etc. | OIL | 9.0 | 7.3 | −7.8 | −8.9 | −0.4 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 2.6 |

| 12. Chemical industry | CHM | 7.6 | 6.6 | −15.1 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 6.9 |

| 13. Nonmetal products | NMM | 8.6 | 8.4 | −21.1 | −4.5 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 5.0 | 9.0 |

| 14. Metallurgy | MET | 8.6 | 7.9 | −5.3 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 6.3 |

| 15/16. Metal products–General and specialist machinery | FMP | 6.3 | 6.0 | −26.6 | −2.7 | 9.9 | 7.7 | 5.6 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 11.4 |

| 17. Transport equipment | TEQ | 3.9 | 1.8 | −30.0 | −11.0 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 10.1 | 7.3 | 10.2 |

| 18/19. Electrical–Electronic equipment | EEQ | 3.9a | 1.8a | −30.0a | –a | 10.4 | 8.8 | 2.0a | 2.2a | 3.7a | 7.0a |

| (11.2) | (12.0) | (−19.3) | (4.8) | (10.7) | (13.7) | (11.9) | (12.0) | ||||

| 20. Instrument and meter | OME | 11.0 | 3.4 | −27.4 | 2.0 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 6.6 | 9.4 | 3.8 | 3.0 |

| 21. Other manufacturing | OMF | 1.3 | −3.9 | −25.0 | −12.9 | −4.8 | −5.4 | −7.1 | −0.4 | 0.4 | 4.0 |

| 22. Electricity and hot water production and supply | ELE | 6.8 | 7.0 | −6.0 | −1.7 | −0.2 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 5.9 | 4.2 |

| 23. Gas and water production and supply | GAS | 6.6 | 6.6 | −6.0 | −0.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| Average | 5.2 | 4.8 | −18.4 | −3.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 5.0 |

We only include manufacturing sectors. Based on authors’ compilation from China’s National Bureau of Statistics and concordance between IO sectors and industrial sectors in the industrial classification for national economic activities in Guobiao (GB)/T 4754–2011. We use the average year-on-year growth rate of all GB sectors that correspond with the IO sector as the growth rate of a specific IO sector. Please note that the data are for enterprises with annual revenue above 20 million RMB and we combine metal and non-metal mining (sector 4 and 5), and metal products and general and specialist machinery (sector 15 and 16) to be consistent with the sectors in the general equilibrium trade model.

aFor WAP and EEQ, values in bold value are the actual shocks used in the modeling, and values in brackets are the raw data in the CARD database. Note that for several sectoral shocks (labeled as “—”), we cannot find a reasonable value and omit them in the modeling.

Similar to how Barrot et al. (2021) and Dingel and Neiman (2020) find that the impacts of COVID are different across sectors, we find the large variation in value-added growth rate across sectors reflects the large variation of labor productivity changes across sectors in China.

General equilibrium structure

To quantify the implied labor productivity and trade shocks that fit the observed data, we formulate a benchmark mathematical representation of the Chinese economy. Our formulation relies on Mathematical Programming System for General Equilibrium (mpsge) (Rutherford 1999) as a modeling environment embedded within the General Algebraic Modeling System (GAMS) (Brooke et al. 1988) software. mpsge offers a convenient representation of a standard general equilibrium as a mixed complementary problem in the Mathiesen-Rutherford tradition.9

The general structure of a Mathiesen-Rutherford general equilibrium defines a set of complementary-slack conditions around markets indexed by p, transformation activities indexed by q, and households indexed by h. Let us define the variable Xq as a quantity index on a constant-returns activity that transforms inputs into outputs. The associated unit value functions represent the technology and optimizing behavior. That is, the minimized unit-cost function, cq(p), where p is the vector of prices, gives the marginal cost. The maximized unit-revenue function rq(p) gives us the marginal revenue.10 With initial quantity x0q, we can represent the optimized profit function as

Activities intensify up to the point that they drive profits to zero in a competitive general equilibrium. The following represents the complementary-slack condition as indicated in the mpsge software:

| 1 |

Logically, the three conditions embedded in (1) indicate that unit profits are zero for any activity with positive output (x0qXq > 0), but output is zero for an unprofitable activity. Also note that the constant-returns assumption on technologies allows us to eliminate the benchmark output level, x0q, from (1), which is a convenient default scaling such that the activity level, Xq, is an index. Of course, one might multiply through each condition in (1) by x0q without changing the economics of the problem.

The next set of conditions are the market clearance conditions associated with the prices. Let Pp be an element of the price vector, p. Any scarce commodity will have a strictly positive price, and supply will equal demand. The sources of supply include endowments and outputs from activities, and the sources of demand include final demand and inputs to activities. Let the endowment of commodity p to household h be Eph. The Marshallian demand functions Dph(p, Wh), where Wh gives the total income for household h, indicate final demand for commodity p. We recover demands and supplies from transformation activities by applying the envelope theorem (Hotelling’s lemma). The complementary-slack condition generated through the mpsge software is

| 2 |

The default chooses units such that all Pp are one at the benchmark equilibrium. This is a convenient scaling such that the prices are indexes.

The next set of equilibrium conditions determine the nominal income levels for each agent or household h. Expenditures cannot exceed the value of endowments plus net tax revenues. Let Th indicate the total net tax revenues allocated to agent h such that the complementarity condition is

| 3 |

While the technical formulation depends on a multitude of complementary-slack conditions, some conditions will logically simplify to equality constraints. For example, in condition (3) we will always have Wh = ∑pPpEjh + Th > 0 for any non-trivial household. Conditions (1), (2), and (3) represent the core set of equilibrium conditions. The conditions only indicate relative prices, thus we establish a price normalization that indicates the units associated with nominal measures. The numeric solution includes activity indexes, relative prices, and nominal incomes.

Adding auxiliary variables and related conditions or constraints introduces considerable flexibility into the competitive general equilibrium. Within mpsge these affect the core equilibrium in the form of endogenous taxes and endowment adjustments. For example, tax rates might be adjusted to meet a given revenue target, or labor supply might be rationed to meet a given minimum wage. In the context of our analysis, we introduce a set of COVID-19 productivity and trade shocks that adjust endogenously to move the benchmark equilibrium to the observed 2020 data. The goal is to compute, report, and interpret these shocks.

Table 4 outlines the full set of variables in our model of the Chinese economy. We classify these variables into the mpsge categories with descriptions and dimensions. To facilitate the description, it is useful to define the sets embodied in the data. Let the indexes i ∈ I or j ∈ I indicate an industry or its associated commodity. Let r ∈ R indicate a Chinese province or region, and let s ∈ S indicate a foreign trade partner.11 The set G is the union of I and R (g ∈ G = I ∪ R). This is useful because we aggregate inputs of good j (across domestic and imports) for industry i and for final demand in region r. Thus, the input demand activity, IDigr, provides an Armington aggregation over domestic and foreign varieties to industries and the regional household. Note in Table 4 that the acronym “CET” indicates a constant-elasticity-of-transformation activity where a single input transforms into multiple outputs. We also use the acronym “CES” to indicate standard constant-elasticity-of-substitution technologies.

Table 4.

Scope of China regional model

| Variable | Description | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Transformation Activities (Xq) | ||

| Yir | Production | I × R |

| CETir | CET supply: domestic versus foreign | I × R |

| IDigr | Armington aggregation: domestic and foreign | I × I × R |

| Ajr | Armington aggregation: domestic-provincial goods | I × R |

| Mi | Armington aggregation: foreign | I |

| MBis | Bilateral import | I × S |

| KXr | CET activity for sector-specific capital | R |

| Ur | Utility (final demand) | R |

| Markets (Pp) | ||

| PYir | Output price (input to domestic-foreign CET) | I × R |

| PRir | Regional output price for domestic use | I × R |

| PXi | Export price | I |

| PIigr | Top-level Armington price of i input to g | I × I × R |

| PAir | Armington composite over provincials | I × R |

| PMi | Armington composite over imports | I |

| PMBis | Bilateral import price | I × S |

| RKir | Sector-specific capital price | I × R |

| RKXr | Price of generic capital endowment | R |

| PLr | Wage rate | R |

| PUr | True-cost-of-living index | R |

| PFX | Price of foreign exchange (numeraire) | 1 |

| Households (Wh) | ||

| RAr | Provincial Representative Agent Income | R |

| ROW | Rest of world (export-demand import-supply agent) | 1 |

| Auxiliary | ||

| XDi | Export demand (constant elasticity) | I |

| ρr | Provincial-labor rationing index | R |

| ϕi | Sectoral targeting parameter (phantom subsidy) | I |

| τ | Export-demand shock index | 1 |

| υ | Balance-of-payments (capital-account) rationing | 1 |

We calibrate the model to the China MRIO table developed by Mi et al. (2018). We structure the model around the data with CES and CET technologies. Each transformation activity in Table 4 will be associated with an equilibrium condition analogous to (1). Calibration involves specifying the CES and CET unit value functions, cq(p) and rq(p), and endowments such that the social accounts satisfy the equilibrium conditions. Each price and income-level variable declared in Table 4 will have an associated equilibrium condition analogous to (2) and (3). In our application, there are deviations from the generalized structure, which we now elaborate.12

First, we outline our non-standard treatment of utility and final demand. We abstract from multiple household types within a region and alternative final demand categories. Thus, for each region, there is a single representative-agent expenditure function covering private consumption, investment, and government spending. It is convenient to replace the Marshallian demand functions in (3) by explicitly modeling the representative agent’s expenditures as a linearly-homogeneous “utility” activity Ur. Let er(p) be a Cobb-Douglas unit expenditure function calibrated to each region’s final demand, and let PUr be the true-cost-of-living index (or price of utility). The equilibrium conditions when we model utility as an activity (while noting that there will be no slack agents) are

| 4 |

Introducing the price of utility has associated market clearance conditions:

| 5 |

For any other commodity’s market-clearance condition, we replace the Marshallian demands in (2) with compensated or conditional demands, which are a function of the level of utility. This formulation is convenient because Ur is a theoretically consistent index of utility evaluated at initial prices. Equivalent variation is , where u0r is benchmark nominal expenditures. The computed equilibrium is equivalent to specifying the Marshallian demand functions as indicated in (2) and (3), but having a direct welfare report motivates the treatment of utility as a transformation activity.

We proceed with an explanation of the formulation of international and inter-regional trade. On the import side, the import activities, MBis, transform the foreign-exchange good trading at price PFX into a bilateral import good, trading at price PMBis for good i from foreign region s. These bilateral import goods are, in turn, transformed into a CES Armington composite of foreign goods, with the composite trading at a price PMi for good i through activity Mi. Inter-regionally, the composite good in region r trading at a price PAir is a CES aggregate of imported domestic goods from other provinces. Finally, the activity IDigr aggregates home-province goods with the foreign and domestic composites to produce the input of good i for sector g in region r, PIigr.

Moving to the export side, we explain our export-demand formulation. The activity CETir transforms productive output into either an export good trading at a price PXi or a region-specific domestic good trading at a price PRir. The export good is sold to generate foreign-exchange at price PFX. The market-clearance condition on PFX is the balance-of-payments constraint, as export activities generate foreign exchange (and the capital-account surplus) and foreign exchange is used to buy imports. We add an agent, with income ROW, to facilitate the formulation. The added auxiliary variable XDi rations the rest-of-world demand for China’s exports to be consistent with a large-open-economy structure. Let xd0i be the benchmark level of exports of good i, and let the export-demand function be , where the arguments are the price of exports and the price of foreign exchange. We add the complementary-slack relationship for the index XD to the model:

| 6 |

The export-demand function is the sum of the conditional demands across trade partners s indicated by the nested CES Armington structure in the gtapingams model.13 With a finite export demand elasticity, we have a large-open-economy structure where there are adverse terms-of-trade effects of expanded trade. Export demand falls as PFX rises, but export demand contracts as PX rises.

We introduce the endogenous variable τ in equation (6), which is an export-demand shifter fixed at one if there is no international-trade targeting in the scenario. If we do want to account for changes in China’s international trade opportunities induced by the COVID-19 shocks, we adjust τ to hit a given export target, and we adjust υ to hit a given import target. First, we consider export targeting. Let be the exogenous target for aggregate exports. The following complementary slack condition is associated with τ:

| 7 |

Similarly, we have a condition for import targeting:

| 8 |

where mt0i is the benchmark level of good i imports and is the import target. The variable υ does not directly impact the productivity of imports, but rather rations the foreign exchange good as it is transferred to Chinese agents through the capital account. In general targeting, both imports and exports will indicate an adjustment in the capital account balance. Equation (7) determines the foreign exchange generated through exports. Rationing the transfers of PFX through the capital account yields the appropriate level of aggregate imports, which the regional agent’s budget best illustrates. Let the labor and capital endowments be and . Denote the benchmark net trade surplus as observed in the accounts, which if positive indicates a transfer of foreign exchange to foreign agents through a capital account deficit. In the benchmark calibration, a negative endowment of PFX represents this transfer. Then, the following gives the nominal income for the representative agent:

| 9 |

Under trade targeting, υ adjusts according to (8) such that the amount of foreign exchange available sufficiently meets the import target. If we do not have trade targeting, υ = 1 and we ignore (8). That is, without trade targeting we have the standard assumption that there is no change in the net trade surplus.

In the regional budget (9) we include ρr as the instrument for adjusting the productivity of the regional labor force. Notice that we can interpret the adjustments in as any combination of adjustments in the quantity of labor or productivity per worker. Distinguishing across these margins requires additional information. As with the rest of the model, a complementarity condition determines ρr. Let give the proportional value-added target relative to the benchmark. The equilibrium condition associated with ρr is:

| 10 |

The value-added target is interpreted as a real target and thus the first term in (10) is devoid of prices. Value-added in the model, however, is inherently a nominal measure once the component prices move away from their benchmark normalization. Dividing the measured value-added by PFX makes it explicit that the real constraint is in numeraire units.14

The final model extension indicates our approach to sectoral targeting. We add the instrument ϕi and associated complimentarity condition to the model such that we are able to target the output of a given sector across the Chinese economy. Consider that, in the equilibrium, a pure productivity shock for a given activity is equivalent to one plus an ad valorem subsidy or tax that collects no revenue. Researchers sometimes refer to this in the literature as a phantom tax or subsidy (Dixon and Rimmer 2002). To illustrate, we first present the complementarity condition for production inclusive of the instrument. Consistent with (1), there is a complementarity condition for production in each region and sector:

| 11 |

The instrument ϕi enters as a uniform endogenous subsidy on the unit revenue in sector i across all regions r. The equivalent total-productivity-shock associated with a non-zero ϕi is (1 + ϕi) = TFPi. For example, if ϕi = 0.1, then productivity of inputs increase by 10%, which is equivalent to a new unit-cost function .15 Denoting the sectoral target , we include the following condition to determine the ϕi:

| 12 |

In the first term, unit consistency requires a nominal summation across regions. Again, we divide by PFX to maintain homogeneity in prices, and to indicate that the real constraint is in numeraire units. Notice that we bind ϕi to be greater than (−0.99), and ad valorem subsidy no lower than −99%, so that unit revenue does not approach zero in computation.16

This section elaborates on the key features and model extensions as implemented in our analysis. The computer code is available from the authors upon request. In the next section, we present the results of our analysis.

Results

Regional labor productivity shocks

Tables 5 and 6 in the Appendix provide two full sets of COVID-19 province-by-month labor-productivity-shock estimates for 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 including and not including trade shocks as modeling targets, respectively. In February 2020, as a year-on-year comparison, when compared with February 2019 levels and when trade series are included in the modeling, we find an average 39.5% decrease in labor productivity (equivalent to around 305 million jobs) and an average 25.9% decrease in welfare across provinces.17 Both China’s labor productivity and welfare have quickly returned to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020. As of September 2020, average labor productivity increased by 12.2% (equivalent to around 94 million jobs) and average welfare increased by 8.2% compared to September 2019 levels.

Table 5.

Calculated year-on-year labor productivity shocks in observed sectoral and provincial value-added targets (%)

| Provinces | Region | 2019 GDPa | Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangdong | South-central | 1563.7 | 23.9 | 18.9 | −53.5 | −16.7 | 12.9 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 28.2 | 30.9 | 39.0 |

| Jiangsu | East | 1428.6 | 31.1 | 24.8 | −46.0 | 4.7 | 26.9 | 25.1 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 32.4 | 44.5 |

| Shandong | East | 1021.4 | 20.5 | 9.5 | −42.9 | −3.6 | 17.4 | 21.2 | 17.5 | 19.6 | 36.9 | 42.0 |

| Zhejiang | East | 904.4 | 32.9 | 21.3 | −57.3 | −8.5 | 31.9 | 32.3 | 14.2 | 18.4 | 36.0 | 42.8 |

| Henan | South-central | 777.8 | 22.8 | 13.8 | −30.4 | 2.9 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 8.7 | −2.5 | 8.4 | 13.6 |

| Sichuan | Southwest | 671.3 | 25.4 | 19.3 | −22.7 | 7.2 | 18.7 | 17.2 | 11.1 | 15.0 | 15.4 | 26.7 |

| Hubei | South-central | 657.8 | 16.6 | 15.1 | −74.1 | −72.9 | −2.2 | 7.3 | 2.7 | 7.2 | 13.9 | 19.4 |

| Fujian | East | 612.9 | 24.5 | 16.6 | −38.3 | 0.8 | 13.3 | 16.8 | 10.6 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 23.5 |

| Hunan | South-central | 577.7 | 25.5 | 17.9 | −25.6 | 7.2 | 16.7 | 12.1 | 11.0 | 15.3 | 19.5 | 23.8 |

| Shanghai | East | 550.1 | 23.1 | 35.3 | −60.6 | −40.0 | 14.9 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 51.0 | 37.6 | 41.8 |

| Anhui | East | 533.5 | 19.8 | 16.5 | −33.1 | 12.6 | 26.8 | 23.1 | 16.1 | 12.8 | 24.9 | 28.3 |

| Beijing | North | 513.2 | 8.0 | 10.5 | −43.9 | −34.4 | 14.9 | 14.8 | 25.4 | 31.6 | 20.5 | 22.1 |

| Hebei | North | 506.5 | 7.3 | 11.0 | −25.0 | 2.3 | 13.1 | 16.9 | 5.6 | 14.7 | 16.9 | 19.7 |

| Shaanxi | Northwest | 373.5 | 19.5 | 21.9 | −33.2 | 5.9 | 18.5 | 26.5 | −1.6 | 2.0 | 22.8 | 18.1 |

| Liaoning | Northeast | 359.9 | 20.9 | 10.5 | −28.1 | −25.0 | 6.6 | 15.4 | 4.6 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 18.4 |

| Jiangxi | East | 357.2 | 47.0 | 28.1 | −47.4 | 24.2 | 32.9 | 25.0 | 27.1 | 31.3 | 34.5 | 46.3 |

| Chongqing | Southwest | 341.8 | 27.1 | 21.9 | −54.8 | 11.4 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 28.2 | 40.9 | 36.1 | 37.3 |

| Yunnan | Southwest | 336.3 | −19.1 | −22.0 | −42.3 | −9.2 | 0.2 | 43.8 | 29.6 | 34.4 | 43.6 | 28.8 |

| Guangxi | South-central | 307.5 | 25.8 | 12.8 | −37.4 | −7.6 | 5.6 | 17.3 | 5.6 | 15.7 | 15.1 | 18.9 |

| Inner Mongolia | North | 249.2 | 5.6 | −0.8 | −27.0 | −5.8 | 6.5 | −8.5 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 3.8 |

| Shanxi | North | 245.6 | 13.9 | 2.6 | −34.5 | 22.1 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 9.6 | 16.2 | 37.6 | 52.7 |

| Guizhou | Southwest | 242.8 | 22.5 | 32.3 | −33.7 | 27.9 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 14.8 | 20.0 | 14.3 | 25.0 |

| Tianjin | North | 203.5 | 30.3 | 13.6 | −46.9 | −43.3 | −2.0 | 22.8 | 14.6 | 47.1 | 36.3 | 42.6 |

| Xinjiang | Northwest | 196.9 | 11.6 | 3.4 | −14.7 | 11.8 | 19.9 | 27.1 | 29.8 | 15.3 | 12.3 | 36.5 |

| Heilongjiang | Northeast | 196.1 | 1.6 | 23.6 | −41.3 | −19.8 | 13.4 | 5.7 | −2.3 | 0.0 | 36.4 | 42.6 |

| Jilin | Northeast | 169.8 | 49.0 | 51.1 | −63.9 | −22.4 | 17.2 | 58.1 | 74.4 | 48.2 | 42.7 | 85.7 |

| Gansu | Northwest | 126.2 | 31.4 | 19.6 | −20.6 | −18.3 | 26.6 | 45.1 | 19.9 | 21.1 | 32.1 | 24.7 |

| Hainan | South-central | 77.2 | 19.4 | 20.9 | −37.5 | −20.2 | −7.9 | −12.6 | −14.4 | 13.0 | 5.3 | 5.0 |

| Ningxia | Northwest | 54.3 | 18.0 | 28.2 | −9.5 | 26.4 | 21.0 | 11.4 | 17.2 | −32.3 | 9.4 | 17.4 |

| Qinghai | Northwest | 42.6 | 40.6 | 38.6 | −24.5 | 25.7 | 12.7 | 16.1 | 9.5 | 18.2 | 23.0 | 2.4 |

| East | 5408.1 | 27.7 | 19.5 | −45.1 | 1.2 | 24.0 | 23.3 | 17.3 | 21.2 | 31.9 | 39.2 | |

| South-central | 3961.7 | 23.0 | 16.2 | −43.8 | −15.1 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 7.4 | 13.5 | 18.4 | 24.0 | |

| North | 1718.1 | 10.6 | 7.7 | −31.6 | −3.2 | 9.3 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 17.9 | 21.9 | 26.7 | |

| Southwest | 1592.3 | 14.3 | 12.1 | −34.5 | 7.6 | 14.2 | 24.7 | 18.9 | 24.7 | 25.3 | 28.6 | |

| Northeast | 1275.9 | 17.8 | 21.1 | −34.9 | −18.9 | 9.8 | 19.0 | 16.4 | 14.8 | 24.2 | 36.5 | |

| Northwest | 793.5 | 21.8 | 18.2 | −23.3 | 3.7 | 20.7 | 29.8 | 13.5 | 8.8 | 21.7 | 23.3 | |

| Average | 473.3 | 21.2 | 17.6 | −37.9 | −5.0 | 14.6 | 18.9 | 14.3 | 18.1 | 24.3 | 29.8 |

This table presents calculated year-on-year labor productivity shocks across 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 using only value-added targets in the modeling. Please note that China’s National Bureau of Statistics does not report year-on-year growth rate of value-added in January, and the productivity shocks in February denote the productivity shocks from January to February. Labor productivity shocks in regions are population-weighted average labor productivity shocks across provinces in a region.

aGDP is measured in $US billion.

Table 6.

Calculated year-on-year labor productivity shocks in observed sectoral and provincial value-added and national trade targets (%)

| Provinces | Region | 2019 GDPa | Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangdong | South-central | 1563.7 | 11.1 | 20.9 | −64.0 | −8.5 | −9.0 | −18.7 | 27.2 | 33.6 | 14.8 | 13.6 |

| Jiangsu | East | 1428.6 | 19.0 | 12.1 | −60.3 | 9.3 | 26.2 | 22.4 | 42.2 | 32.6 | 32.5 | 37.6 |

| Shandong | East | 1021.4 | 12.7 | 10.8 | −49.8 | 5.7 | 36.5 | 38.1 | 30.4 | 22.8 | 25.3 | 25.8 |

| Zhejiang | East | 904.4 | 23.0 | 16.8 | −66.0 | −0.8 | 45.8 | 43.6 | 28.9 | 25.3 | 30.3 | 31.8 |

| Henan | South-central | 777.8 | 19.7 | 22.8 | −28.4 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 5.4 | 8.4 | −6.7 | −2.3 | 0.9 |

| Sichuan | Southwest | 671.3 | 18.6 | 21.9 | −29.7 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 8.7 | 19.1 | 16.0 | 7.0 | 14.2 |

| Hubei | South-central | 657.8 | 11.3 | 13.2 | −76.8 | −72.0 | 3.3 | 12.3 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 13.6 |

| Fujian | East | 612.9 | 16.9 | 20.3 | −47.1 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 19.8 | 17.3 | 5.9 | 7.8 |

| Hunan | South-central | 577.7 | 19.9 | 19.5 | −30.8 | 12.5 | 16.5 | 10.5 | 18.2 | 16.5 | 12.4 | 13.9 |

| Shanghai | East | 550.1 | 9.6 | 43.5 | −68.8 | −31.5 | −5.2 | −11.1 | 33.6 | 54.8 | 14.4 | 9.9 |

| Anhui | East | 533.5 | 15.3 | 19.1 | −37.1 | 17.9 | 27.6 | 21.6 | 21.1 | 12.9 | 17.3 | 18.4 |

| Beijing | North | 513.2 | 0.7 | 18.9 | −49.5 | −26.1 | 12.5 | 7.9 | 41.6 | 32.0 | 3.1 | −0.1 |

| Hebei | North | 506.5 | 3.5 | 12.6 | −29.4 | 6.9 | 14.5 | 16.1 | 12.2 | 16.1 | 11.0 | 11.5 |

| Shaanxi | Northwest | 373.5 | 15.6 | 31.5 | −32.0 | 14.7 | 19.5 | 22.6 | 1.0 | −1.6 | 9.6 | 3.3 |

| Liaoning | Northeast | 359.9 | 16.7 | 13.5 | −32.1 | −21.2 | 8.6 | 16.1 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 6.8 | 9.4 |

| Jiangxi | East | 357.2 | 31.5 | 29.6 | −55.8 | 35.2 | 23.4 | 12.5 | 44.0 | 35.5 | 18.5 | 21.2 |

| Chongqing | Southwest | 341.8 | 21.3 | 25.5 | −58.2 | 17.0 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 35.7 | 39.7 | 26.3 | 25.4 |

| Yunnan | Southwest | 336.3 | −19.2 | 1.7 | −28.2 | −0.1 | −24.8 | 6.8 | 15.5 | 13.0 | 10.2 | −4.1 |

| Guangxi | South-central | 307.5 | 21.4 | 23.6 | −37.4 | −1.2 | −2.4 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 10.0 | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| Inner Mongolia | North | 249.2 | −0.3 | 8.2 | −30.1 | 5.3 | 11.5 | −7.9 | 8.7 | −1.5 | −9.0 | −14.0 |

| Shanxi | North | 245.6 | 12.2 | 17.8 | −26.0 | 30.7 | −1.1 | −3.5 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 17.9 | 29.5 |

| Guizhou | Southwest | 242.8 | 18.9 | 47.8 | −29.9 | 37.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 13.4 | 12.1 | −1.6 | 5.7 |

| Tianjin | North | 203.5 | 23.5 | 22.9 | −49.9 | −38.3 | −11.0 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 44.0 | 18.9 | 20.5 |

| Xinjiang | Northwest | 196.9 | 9.4 | 17.9 | −10.0 | 20.8 | 12.7 | 15.5 | 27.2 | 6.3 | −4.6 | 14.6 |

| Heilongjiang | Northeast | 196.1 | −3.4 | 34.6 | −42.1 | −12.0 | 13.7 | 1.6 | 2.3 | −3.2 | 18.4 | 20.1 |

| Jilin | Northeast | 169.8 | 46.0 | 68.2 | −60.9 | −16.4 | 20.1 | 62.2 | 72.1 | 35.7 | 25.9 | 65.4 |

| Gansu | Northwest | 126.2 | 27.9 | 36.0 | −15.0 | −11.9 | 13.1 | 25.2 | 16.9 | 11.7 | 11.9 | 3.5 |

| Hainan | South-central | 77.2 | 13.1 | 33.5 | −38.0 | −12.3 | −15.8 | −24.1 | −12.2 | 7.7 | −11.1 | −14.3 |

| Ningxia | Northwest | 54.3 | 16.3 | 40.4 | −3.3 | 33.6 | 12.4 | 1.8 | 13.9 | −36.8 | −2.0 | 4.2 |

| Qinghai | Northwest | 42.6 | 42.5 | 85.8 | 0.8 | 40.1 | −15.2 | −18.9 | −9.4 | −7.2 | −10.9 | −26.8 |

| East | 5408.1 | 18.1 | 18.1 | −53.7 | 8.8 | 27.9 | 24.7 | 31.8 | 26.3 | 22.9 | 24.6 | |

| South-central | 3961.7 | 16.1 | 20.6 | −47.6 | −9.6 | 2.0 | −0.2 | 15.1 | 13.9 | 7.2 | 8.5 | |

| North | 1718.1 | 6.2 | 14.8 | −33.1 | 3.7 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 14.8 | 15.9 | 9.3 | 11.0 | |

| Southwest | 1592.3 | 9.9 | 22.2 | −33.8 | 14.7 | 3.2 | 9.2 | 19.8 | 18.3 | 9.3 | 10.0 | |

| Northeast | 1275.9 | 14.2 | 28.9 | −35.8 | −14.1 | 11.1 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 22.7 | |

| Northwest | 793.5 | 18.9 | 33.1 | −18.4 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 17.7 | 11.7 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 | |

| Average | 473.3 | 15.8 | 26.4 | −39.5 | 2.1 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 19.5 | 15.6 | 10.3 | 12.2 |

This table presents calculated year-on-year labor productivity shocks across 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 using both value-added and trade series in the modeling. The provinces and regions are ordered based on their GDP in 2019 ($US billion). Please note that the China’s National Bureau of Statistics does not report growth rate of value-added in January, and the productivity shocks in February denote the productivity shocks from January to February. Labor productivity shocks in regions are population-weighted average labor productivity shocks across provinces in a region.

aGDP is measured in $US billion.

For illustration purposes, Figure 2 presents the monthly year-on-year percentage changes in labor productivity in Beijing, Hubei, Heilongjiang, Zhejiang, and Xinjiang. Panel A presents the estimates without trade shocks as additional modeling targets, and panel B presents the estimates with trade shocks as targets.

Fig. 2.

Labor productivity shock estimates in five typical provinces with and without trade shocks (%)

In panel A, compared with levels in February and March 2019, Hubei’s labor productivity reduced by 74.1% and 72.9% in February and March 2020, respectively. However, Hubei’s labor productivity has returned since May 2020 and increased to 19.4% as of September 2020 compared to 2019 levels. This pattern is consistent with the draconian lockdown measures Hubei adopted. Beijing and Zhejiang’s labor productivity reduced by 43.9% and 46.0%, respectively, in February 2020 compared to February 2019 levels, while Xinjiang’s labor productivity reduced by only 14.7% in February 2020 compared to February 2019 levels. These patterns are in line with COVID-19’s spatial progression patterns. In addition, labor productivity in all five examined provinces gradually returned to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020 and reached an average year-on-year growth rate of around 32.0% as of September 2020. While Beijing was initially one of the fastest-recovering provinces (cities), the COVID-19 outbreak in Beijing in August and the associated strict lockdown measures thereafter have since slowed Beijing’s recovery.

Compared with panel A, panel B in Figure 2 accounts for trade shocks and thus shows different recovery patterns. From April to June, labor productivity grew faster when not including trade shocks as additional targets in the modeling. For example, Zhejiang’s labor productivity grew by 31.9%, 32.3%, and 14.2% in April, May, and June, respectively, compared with their 2019 levels when we do not include trade shocks as additional targets, which is lower than its labor productivity year-on-year growth rates of 45.8%, 43.6%, and 28.9% in April, May, and June, respectively, when we include trade shocks as additional targets. The fact that China’s net export demand declined from April to June can explain this pattern. Therefore, to achieve the same output when net export demand remains unchanged, we need to compensate export demand decline with higher labor productivity growth. These patterns reversed in August and September, partially because China’s exports began accelerating in August (this is especially true for provinces in eastern China). As a result, labor productivity growth without trade shocks as targets was smaller than the labor productivity growth with trade shocks in August and September 2020.

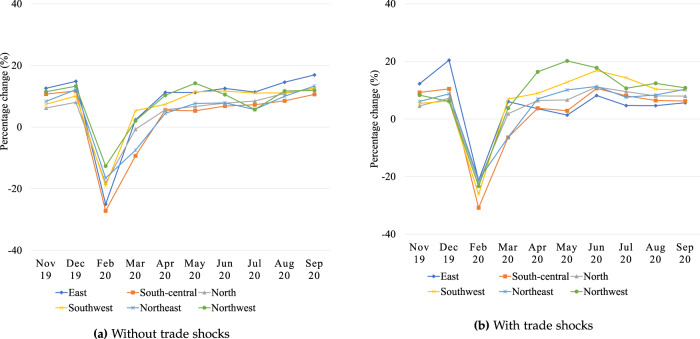

To examine the spatial patterns of labor productivity shocks, we present the monthly population-weighed average labor productivity shocks in six regions in Fig. 3.18 February 2020 shows a clear pattern—provinces in south-central and eastern China were most affected while northwestern provinces were least affected. We also find significant heterogeneity in recovery patterns across regions. Specifically, provinces in eastern China grew fastest from a labor productivity shock of −45.1% in February to 39.2% in September 2020. The labor productivity recovery in northwestern China is most stable and increased from a negative shock of −23.3% in February to 23.3% in September 2020. The south-central region, where Hubei is located, grew from a negative shock of −43.8% in February to 24.0% in September. Similar to provincial patterns, regional recovery patterns from April to June differ depending on whether we account for national trade shocks. Most regions’ labor productivity grew faster in April, May, and June, and reached a smaller growth rate in August and September when we do not include trade shocks. The net-export growth since August 2020 can help explain this change.

Fig. 3.

Labor productivity shock estimates in six regions with and without trade shocks (%). Note: The average labor productivity shock estimates in a region is the average labor productivity shock estimates weighted by 2019 population across provinces

There are several points worthy of attention when interpreting the labor productivity estimates. First, the labor productivity estimates are combinations of COVID-19 pandemic’s productivity and employment effects, which suggests that the labor productivity estimates include changes in employment status, working hours, and output per working hour. Therefore, the estimated 293 million job loss in February 2020 should be interpreted as a 293 million full-time-equivalent job loss that can be any combination of changes in working hours, employment status, or output per working hour.19 Second, the value-added and trade targets used in the CGE modeling are the results of both the COVID-19 pandemic and various government policies, such as deferred tax payments for small and medium-sized firms, lower lending rates, and subsidies for infected medical workers’ compensations. Given it is likely that policy changes and the potential adoption of smart technologies could change labor productivity, the labor productivity estimates derived from the model capture the net impacts of the pandemic and the various government policies. If government policies such as welfare programs increase demand, then we underestimate the negative labor productivity estimates in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given that for each province CNBS only reports year-end employment data and does not provide monthly data, we use the estimated unemployment rate from a survey conducted by China Center for Economic Research to compare our estimated employment effect and the actual employment loss in February 2020.20 This survey tracked the employment status of 4539 workers and reported an average employment rate of 64.92% at the end of February 2020, which suggests an unemployment rate of 36.08%. This impact is similar in magnitude to our estimated national average labor productivity shocks of −37.9% without trade shocks (Table 5 in the Appendix) and −39.5% with trade shocks (Table 6 in the Appendix).

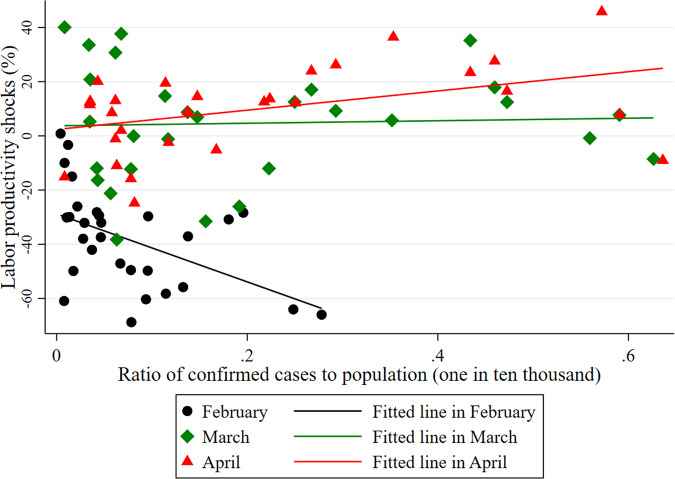

Labor productivity shock estimates and COVID-19 cases

Figure 4 plots the relationship between labor productivity shock estimates and the ratio of cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases in China’s 2019 population in February, March, and April 2020 across provinces. There is a clear negative relationship between ratio of confirmed cases and labor productivity shock estimates in February; however, the negative relation disappears in March and April. This shows that areas hit harder by COVID-19 suffered greater labor productivity loss initially; however, it is only evident in February, which is in line with the fact that the pandemic was largely contained and the economic activities resumed in April 2020.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot of labor productivity shock estimates and ratio of cumulative confirmed cases to population, 2020. Note: We base the ratio of confirmed cases to population on 2019 population. Data on cumulative confirmed cases come from China's Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). Labor productivity shock estimates are estimated with trade shocks as additional targets. For clear illustration, we exclude Hubei from the figure due to its ratio of confirmed cases to population

Regional welfare impacts

Tables 7 and 8 in the Appendix provide two full sets of COVID- 19 province-by-month welfare impacts for 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 estimated from models with and without trade shocks as additional targets, respectively. We base our welfare calculations on equivalent variation and measure households’ money-metric income loss (gain). Figure 5 presents the monthly percentage changes in welfare in Beijing, Hubei, Heilongjiang, Zhejiang, and Xinjiang. Panel A shows welfare changes without trade shocks as targets, and panel B shows the estimated welfare impacts when we incorporate national shocks in the modeling. Compared with the monthly levels in 2019, Hubei’s welfare reduced by 54.1% and 54.3% in February and March 2020, respectively, and returned to a growth rate of 3.9% in May 2020. In addition, although Xinjiang’s value-added only fell by 0.7% in February 2020 (as shown in Table 2), its welfare fell by 8.8% that same month, which indicates that output impacts might disguise labor productivity and welfare impacts. In addition, welfare in all five provinces returned to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020. By September 2020, relative to September 2019, welfare reached a growth rate of around 17.0%. The welfare shocks over time are consistent with the temporal labor productivity shocks in that Zhejiang rebounded fastest, followed by Beijing. Beijing’s welfare recovery has slowed since August due to a COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, the magnitudes of the percentage changes in welfare are smaller than the percentage changes in labor productivity.

Table 7.

Calculated year-on-year welfare changes in observed sectoral and provincial value-added targets (%)

| Provinces | Region | 2019 GDPa | Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangdong | South-central | 1563.7 | 11.6 | 10.6 | −31.4 | −7.6 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 12.6 | 14.4 | 17.4 |

| Jiangsu | East | 1428.6 | 17.6 | 15.9 | −29.6 | 5.3 | 14.6 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 10.7 | 18.0 | 23.7 |

| Shandong | East | 1021.4 | 10.5 | 6.6 | −16.9 | 0.4 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 16.7 | 17.8 |

| Zhejiang | East | 904.4 | 17.7 | 14.2 | −34.7 | −2.8 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 19.9 | 22.3 |

| Henan | South-central | 777.8 | 13.3 | 9.0 | −13.7 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 6.1 | −0.4 | 7.1 | 9.2 |

| Sichuan | Southwest | 671.3 | 14.6 | 11.4 | −12.3 | 3.8 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 9.8 | 14.9 |

| Hubei | South-central | 657.8 | 11.5 | 11.0 | −54.1 | −54.3 | −1.5 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 9.7 | 11.9 |

| Fujian | East | 612.9 | 13.4 | 10.0 | −20.9 | 1.8 | 6.7 | 8.8 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 12.0 |

| Hunan | South-central | 577.7 | 15.4 | 11.6 | −13.2 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 8.0 | 12.3 | 14.3 |

| Shanghai | East | 550.1 | 10.3 | 16.9 | −32.8 | −19.9 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 19.9 | 15.5 | 16.2 |

| Anhui | East | 533.5 | 12.1 | 10.7 | −21.4 | 4.1 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 15.7 | 17.0 |

| Beijing | North | 513.2 | 6.1 | 6.7 | −25.5 | −19.1 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 14.3 | 15.4 | 12.0 | 11.9 |

| Hebei | North | 506.5 | 7.0 | 8.0 | −16.9 | 1.2 | 8.2 | 10.4 | 5.5 | 9.2 | 12.7 | 14.6 |

| Shaanxi | Northwest | 373.5 | 12.6 | 12.9 | −15.8 | 2.5 | 9.0 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 14.2 | 11.4 |

| Liaoning | Northeast | 359.9 | 14.0 | 8.5 | −13.6 | −13.4 | 4.1 | 8.9 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 9.7 | 11.8 |

| Jiangxi | East | 357.2 | 16.3 | 12.0 | −22.7 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 9.1 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 12.7 | 15.7 |

| Chongqing | Southwest | 341.8 | 14.8 | 12.1 | −34.5 | 5.1 | 13.3 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 18.8 | 19.1 | 19.4 |

| Yunnan | Southwest | 336.3 | −5.9 | −7.1 | −19.6 | −2.8 | 1.0 | 17.4 | 12.7 | 13.2 | 18.9 | 13.4 |

| Guangxi | South-central | 307.5 | 15.4 | 9.5 | −16.9 | −1.3 | 3.1 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 5.7 | 9.6 | 11.1 |

| Inner Mongolia | North | 249.2 | 5.4 | 3.2 | −7.4 | −0.1 | 3.6 | −2.6 | 1.7 | −1.5 | 4.2 | 2.9 |

| Shanxi | North | 245.6 | 9.4 | 3.7 | −17.9 | 9.1 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 18.1 | 23.2 |

| Guizhou | Southwest | 242.8 | 12.4 | 16.2 | −19.8 | 11.6 | 5.4 | 6.4 | 8.8 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 13.9 |

| Tianjin | North | 203.5 | 13.4 | 7.3 | −22.4 | −19.2 | −0.2 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 16.2 | 15.3 | 17.4 |

| Xinjiang | Northwest | 196.9 | 8.1 | 4.0 | −8.8 | 5.4 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 15.0 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 19.5 |

| Heilongjiang | Northeast | 196.1 | 2.4 | 10.0 | −19.1 | −8.6 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 14.6 | 16.4 |

| Jilin | Northeast | 169.8 | 16.8 | 17.7 | −28.6 | −7.7 | 6.4 | 17.5 | 21.6 | 13.7 | 15.2 | 26.0 |

| Gansu | Northwest | 126.2 | 17.6 | 11.7 | −13.1 | −10.3 | 13.1 | 20.9 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 18.5 | 14.8 |

| Hainan | South-central | 77.2 | 10.4 | 10.7 | −17.4 | −9.1 | −2.9 | −4.7 | −4.2 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 3.9 |

| Ningxia | Northwest | 54.3 | 12.0 | 16.3 | −8.9 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 6.5 | 11.1 | −15.6 | 8.6 | 12.5 |

| Qinghai | Northwest | 42.6 | 14.1 | 12.7 | −13.6 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 10.0 | 4.2 |

| East | 5408.1 | 12.6 | 14.8 | −25.0 | 2.3 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 11.4 | 14.6 | 16.9 | |

| South-central | 3961.7 | 10.7 | 11.8 | −27.2 | −9.3 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 8.5 | 10.6 | |

| North | 1718.1 | 6.2 | 8.1 | −18.1 | −0.7 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 11.0 | 12.6 | |

| Southwest | 1592.3 | 7.4 | 10.1 | −19.0 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 11.4 | 11.7 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 12.7 | |

| Northeast | 1275.9 | 8.3 | 12.2 | −16.5 | −7.5 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 10.0 | 13.3 | |

| Northwest | 793.5 | 11.5 | 13.3 | −12.6 | 2.0 | 10.3 | 14.2 | 10.5 | 5.7 | 11.7 | 11.9 | |

| Average | 473.3 | 11.7 | 10.1 | −20.8 | −3.1 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 12.8 | 14.7 |

Note: This table presents calculated year-on-year welfare changes across 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 using only value-added targets in the modeling. The provinces and regions are ordered based on their GDP in 2019 ($US billion). Please note that the China’s National Bureau of Statistics does not report growth rate of value-added in January, and the productivity shocks in February denote the productivity shocks from January to February. Welfare shocks in regions are population-weighted average welfare shocks across provinces in a region.

aGDP is measured in $US billion.

Table 8.

Calculated year-on-year welfare changes in observed sectoral and provincial value-added and national trade targets (%)

| Provinces | Region | 2019 GDPa | Nov 19 | Dec 19 | Feb 20 | Mar 20 | Apr 20 | May 20 | Jun 20 | Jul 20 | Aug 20 | Sep 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangdong | South-central | 1563.7 | 8.2 | 16.8 | −31.9 | −3.4 | −4.4 | −10.7 | 7.3 | 9.9 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| Jiangsu | East | 1428.6 | 18.2 | 36.1 | −14.1 | 11.5 | −8.3 | −13.8 | 0.0 | −6.0 | −3.8 | 0.8 |

| Shandong | East | 1021.4 | 8.0 | 11.7 | −17.1 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 10.2 | 5.6 | 8.6 | 8.0 |

| Zhejiang | East | 904.4 | 16.8 | 27.7 | −27.4 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 5.6 |

| Henan | South-central | 777.8 | 8.6 | 3.3 | −25.6 | 3.8 | 12.6 | 13.4 | 16.0 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 7.5 |

| Sichuan | Southwest | 671.3 | 11.2 | 13.6 | −16.5 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 5.7 | 11.1 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 7.5 |

| Hubei | South-central | 657.8 | 8.8 | 12.9 | −54.8 | −52.9 | −2.5 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 5.4 |

| Fujian | East | 612.9 | 10.7 | 11.9 | −24.9 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 10.5 | 8.7 | 4.7 | 5.7 |

| Hunan | South-central | 577.7 | 12.3 | 13.8 | −16.6 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 4.4 | 11.1 | 8.1 | 6.8 | 6.9 |

| Shanghai | East | 550.1 | 7.3 | 23.8 | −32.6 | −16.0 | −2.1 | −4.7 | 8.4 | 16.9 | 5.5 | 4.1 |

| Anhui | East | 533.5 | 9.6 | 14.9 | −22.5 | 8.1 | 11.3 | 8.8 | 13.1 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 8.5 |

| Beijing | North | 513.2 | 3.2 | 10.7 | −27.7 | −15.1 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 18.9 | 14.7 | 4.5 | 2.6 |

| Hebei | North | 506.5 | 4.5 | 12.0 | −18.3 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 6.0 |

| Shaanxi | Northwest | 373.5 | 8.5 | 11.0 | −23.6 | 6.0 | 12.7 | 15.8 | 9.4 | 6.0 | 11.6 | 6.8 |

| Liaoning | Northeast | 359.9 | 11.3 | 10.8 | −16.6 | −10.5 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| Jiangxi | East | 357.2 | 12.9 | 16.1 | −24.4 | 13.2 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 14.2 | 10.1 | 4.9 | 5.9 |

| Chongqing | Southwest | 341.8 | 12.0 | 15.9 | −35.7 | 8.9 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 17.6 | 17.4 | 12.4 | 11.3 |

| Yunnan | Southwest | 336.3 | −10.9 | −17.3 | −35.4 | −0.7 | 8.3 | 26.0 | 26.1 | 22.1 | 21.0 | 12.6 |

| Guangxi | South-central | 307.5 | 9.9 | 3.2 | −30.2 | 1.2 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 12.7 | 9.8 | 8.3 |

| Inner Mongolia | North | 249.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | −16.9 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 10.1 | 2.7 | 1.7 | −2.1 |

| Shanxi | North | 245.6 | 5.8 | 1.2 | −25.3 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 12.5 | 9.8 | 16.1 | 19.0 |

| Guizhou | Southwest | 242.8 | 8.2 | 12.6 | −28.3 | 15.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 17.1 | 15.6 | 8.3 | 10.8 |

| Tianjin | North | 203.5 | 9.1 | 3.3 | −31.8 | −17.2 | 4.7 | 14.2 | 16.3 | 21.4 | 14.6 | 14.5 |

| Xinjiang | Northwest | 196.9 | 2.5 | −5.7 | −25.2 | 8.2 | 21.8 | 25.7 | 29.3 | 17.8 | 11.3 | 19.3 |

| Heilongjiang | Northeast | 196.1 | −1.0 | 8.7 | −25.5 | −5.5 | 10.1 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 4.0 | 11.9 | 11.8 |

| Jilin | Northeast | 169.8 | 12.4 | 12.1 | −38.6 | −5.6 | 14.0 | 26.1 | 32.2 | 19.6 | 16.1 | 24.8 |

| Gansu | Northwest | 126.2 | 12.9 | 7.7 | −23.2 | −7.6 | 18.6 | 26.4 | 20.9 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 11.1 |

| Hainan | South-central | 77.2 | 5.6 | 5.2 | −28.4 | −6.7 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 12.4 | 5.1 | 2.1 |

| Ningxia | Northwest | 54.3 | 9.5 | 18.6 | −11.6 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 5.4 | 13.7 | −16.0 | 3.9 | 6.4 |

| Qinghai | Northwest | 42.6 | 9.4 | 3.4 | −27.5 | 8.2 | 14.2 | 15.4 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 12.0 | 4.7 |

| East | 5408.1 | 12.2 | 20.4 | −21.3 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 8.1 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 5.7 | |

| South-central | 3961.7 | 9.2 | 10.5 | −30.9 | −6.4 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 10.6 | 8.1 | 6.4 | 6.3 | |

| North | 1718.1 | 4.5 | 7.2 | −21.9 | 1.8 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 11.2 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 8.0 | |

| Southwest | 1592.3 | 5.4 | 6.2 | −26.2 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 12.8 | 16.9 | 14.3 | 10.4 | 9.9 | |

| Northeast | 1275.9 | 6.1 | 8.7 | −21.1 | −6.3 | 7.0 | 10.1 | 11.3 | 7.6 | 8.4 | 10.3 | |

| Northwest | 793.5 | 8.3 | 6.1 | −23.3 | 3.8 | 16.4 | 20.2 | 17.8 | 10.7 | 12.4 | 10.8 | |

| Average | 473.3 | 8.2 | 10.6 | −25.9 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 13.1 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 8.2 |

This table presents calculated year-on-year welfare changes across 30 provinces from November 2019 to September 2020 using both value-added and trade series in the modeling. The provinces and regions are ordered based on their GDP in 2019 ($US). Please note that the China’s National Bureau of Statistics does not report growth rate of value-added in January, and the productivity shocks in February denote the productivity shocks from January to February. Welfare shocks in regions are population-weighted average welfare shocks across provinces in a region.

aGDP is measured in $US billion.

Fig. 5.

Welfare changes in five typical provinces with and without trade shocks (%)

The reason that labor productivity and welfare estimates are different is because we define welfare in changes in equivalent variation, which makes the link between a region’s labor productivity and welfare complex. A region’s change in welfare will reflect the full set of price changes across the equilibrium as they enter the expenditure function (the price of consumer goods rises relative to income).

Another point worthy of mentioning is that the welfare estimates calculated from the general equilibrium model are the net impacts induced by both the pandemic and various demand and supply policies that could potentially affect production. If government subsidies and adoption of technologies affected production, then we could have overestimated the welfare estimates in non-COVID-19 periods.

Figure 6 presents the year-on-year monthly percentage changes in welfare in six regions not including and including trade shocks as additional targets, respectively. Figure 6 shows that patterns are consistent with our welfare estimates—eastern China recovered fastest. Similar to provincial patterns, regional growth patterns from April to June differ depending on whether we account for national trade shocks. Most provinces’ welfare grew faster from April to June, when not accounting for trade shocks, and returned to lower levels starting in August, also when not accounting for trade shocks.

Fig. 6.

Welfare changes in six regions with and without trade shocks (%). Note: The average labor productivity shock in a region is the average labor productivity shock weighted by 2019 population across provinces

It is important to explain why welfare estimates are different with and without trade shocks incorporated in the model. With a positive trade shock, we need a more adverse productivity shock to meet the income target. With the trade shock, however, we get both terms-of-trade changes along with changes in the implied balance-of-payments transfer. Consider a positive export shock with little change in imports. In this case, there is an increase in the current account surplus, which indicates that China is transferring current income to the rest of the world through its increased acquisition of foreign assets (lending). This will generally make the welfare results, which are based on changes in current expenditures, sensitive to the inclusion of trade shocks. In the case without trade shocks we adopt the standard comparative-static assumption that the current account is fixed so there is no change in the implied balance-of-payments transfer.

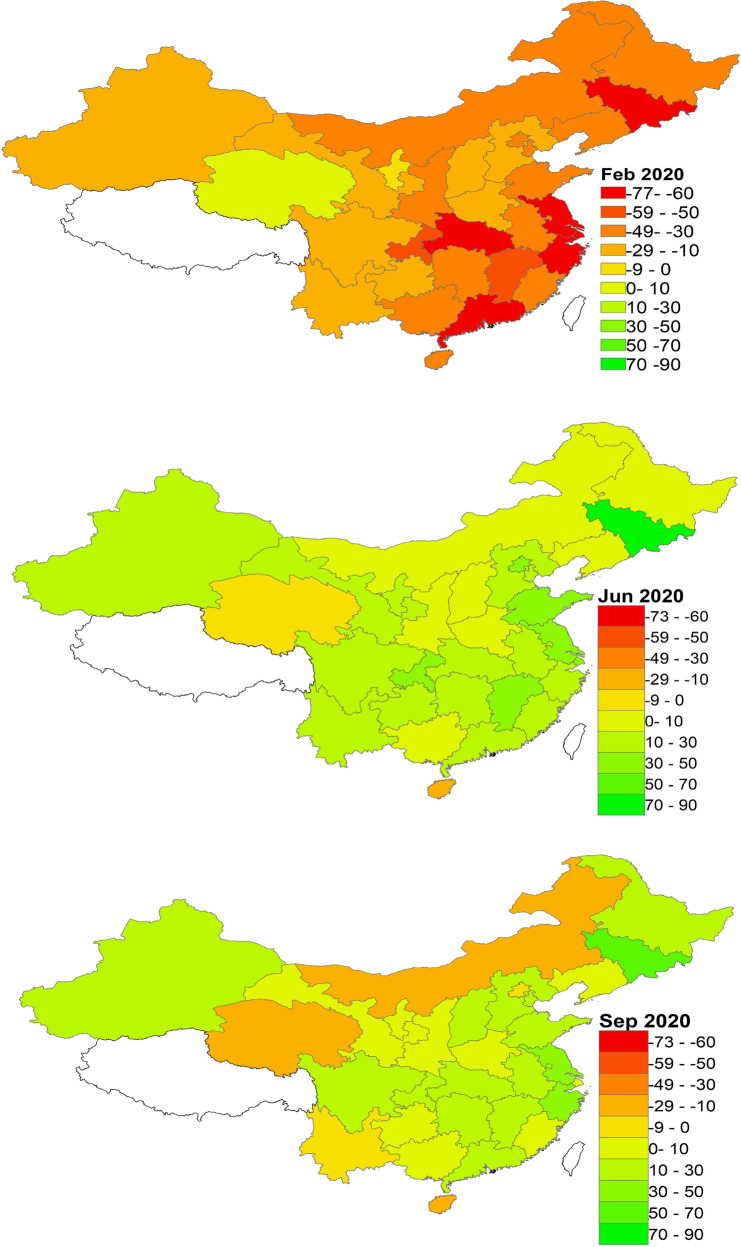

Spatial dynamics of labor productivity shocks

The three maps in Figure 7 illustrate the spatial distribution of estimated provincial labor productivity shocks in February, June, and September 2020 without using national trade shocks as additional targets, which show spatial heterogeneity. While the initial negative labor productivity shocks concentrated in Hubei, eastern China, and parts of northeast and southwest China, the negative labor productivity shocks mostly disappeared in June. The severity of labor productivity shocks relate to provinces’ proximity to Hubei and the stringency of control measures. Eastern China recovered the fastest while south-central provinces recovered slowly. In September, labor productivity shocks in several provinces in northwestern China, such as Qinghai, grew slower than other provinces. The patterns are consistent with the COVID-19 pandemic hitting the northern and northwestern regions in July.

Fig. 7.

Labor productivity shocks in February, June, and September 2020 (%). Note: There are no data for Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan

Conclusion and discussion

This paper first introduces a database that documents various monthly sectoral and regional economic outcomes in China, which we can use to analyze COVID-19’s impacts on China’s economy. We use a general equilibrium model calibrated to a 30 provinces by 30 sectors MRIO table to quantify COVID-19’s impacts on provincial labor productivity and welfare. As a year-on-year comparison, relative to February 2019 levels, when the trade series are included in the modeling, we find an average 39.5% decrease in labor productivity (equivalent to around 305 million jobs) and an average 25.9% decrease in welfare. Labor productivity and welfare quickly return to the recent high-growth trends for China in the latter half of 2020. By September 2020, relative to September 2019, average labor productivity increased by 12.2% (equivalent to around 94 million jobs) and average welfare increased by 8.2%.

In addition, we find heterogeneity in growth patterns across provinces. Provinces in eastern China returned to their normal patterns fastest—we find year-on-year labor productivity shocks of −45.1% in February 2020 and 39.2% in September 2020. The year-on-year labor productivity in northwestern China is most stable and changed from a shock of −23.3% in February to 23.3% in September 2020. The south-central region, where Hubei is located, recovered from a shock of −43.8% in February 2020 to 24% in September 2020. Finally, we find that labor productivity grew faster in the second quarter when we include national trade shocks in the model than when we only use regional and sectoral value-added as output targets.