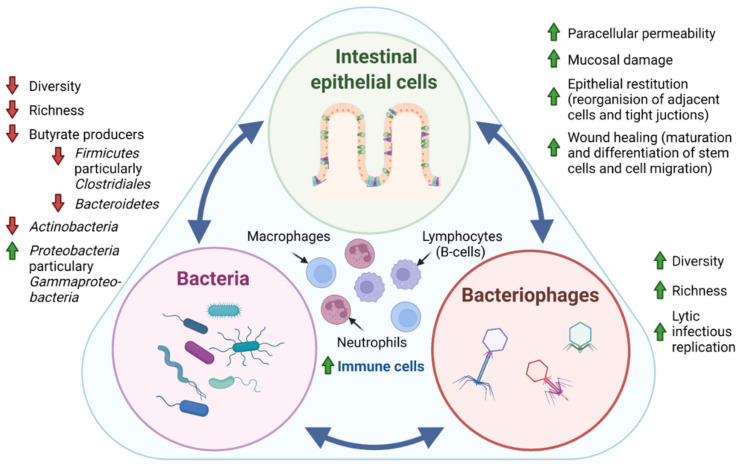

Figure 1.

Tripartite relationship between the intestinal epithelial cells, bacteria, and bacteriophages in IBD pathogenesis. In IBD pathogenesis, bacterial dysbiosis is characterized by decreased bacterial diversity (measure of the number of species in a community, and a measure of the abundance of each species) and richness (number of species in a community) evident by the depletion of the phyla Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes and an enrichment of Proteobacteria. In contrast, studies generally suggest that intestinal bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria, display increased diversity and richness. Interestingly, it has recently been suggested that the temperate phage population displays a shift from lysogenic to lytic replication in patients with IBD [44]. Where intestinal epithelial cells are known to directly regulate the secretion of mucus, antimicrobial peptides, and immune mediators through patterns recognition receptors (PRR), surprising evidence also points towards direct communication between bacteriophages and epithelial cells by adhering to mucosal surfaces, apical-to-basolateral transcytosis, and by the direct delivery of proteins and nucleic acids to eukaryotic cells. Thus, the intestinal epithelial cell layer, intestinal bacteria, and bacteriophages exist in a dynamic tripartite—both mutualistic and parasitic—relationship. Further, sparse studies propose that fungal and protozoan microbiomes are also affected in IBD pathogenesis, displaying both altered diversity and composition. The mechanistic interplay between intestinal epithelial cells, bacteria, bacteriophages, as well as fungi and protozoa, has yet to be unraveled, but would potentially provide insight for future clinical applications of microbiota in IBD. Green arrow: increased, red arrow: decreased.