Abstract

For the authentication of white rice from different geographical origins, the selection of outstanding discrimination markers is essential. In this study, 80 commercial white rice samples were collected from local markets of Korea and China and discriminated by mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics approaches. Additionally, the potential markers that belong to sugars & sugar alcohols, fatty acids, and phospholipids were examined using several multivariate analyses to measure their discrimination efficiencies. Unsupervised analyses, including principal component analysis and k-means clustering demonstrated the potential of the geographical classification of white rice between Korea and China by fatty acids and phospholipids. In addition, the accuracy, goodness-of-fit (R2), goodness-of-prediction (Q2), and permutation test p-value derived from phospholipid-based partial least squares-discriminant analysis were 1.000, 0.902, 0.870, and 0.001, respectively. Random Forests further consolidated the discrimination ability of phospholipids. Furthermore, an independent validation set containing 20 white rice samples also confirmed that phospholipids were the excellent discrimination markers for white rice between two countries. In conclusion, the proposed approach successfully highlighted phospholipids as the better discrimination markers than sugars & sugar alcohols and fatty acids in differentiating white rice between Korea and China.

Keywords: White rice (Oryza sativa L.), Metabolomics, Discrimination marker, Phospholipid, Multivariate analysis

1. Introduction

As a principal food source of the world, rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most important cereal crops. Rice provides approximately more than 20% of the calorific needs for the world population. In particular, in East Asia, it comprises over 70% of the calorific intake [1]. O. sativa L., which is considered to be the “Asian rice”, consists of two subspecies: indica and japonica [2]. Japonica rice is the most common cultivar in East Asia, particularly in three major markets: Korea, China, and Japan [3].

The less milled brown rice does not appeal to most consumers because of its appearance and taste. Consequently, rice in the markets is usually milled to become white rice, where its brown sea coat, germ, and bran are removed. Different types of highly milled white rice look considerably similar, and mislabeling of the white rice origin occurs frequently, especially in East Asia. To find effective discriminating factors, except genetic markers, for plant materials from different locations, we usually consider variables those significantly affect the cellular processes in the plant, such as the annual temperature, drought, cultivate techniques, and biological hazards [4]. Among these variables, temperature is known for its significant effect on the starch and oligosaccharide metabolism [5]. The alterations of this mechanism caused by different annual temperatures induce the aberrant of the associated metabolites. In other words, the temperature of the growth fields alters the metabolic regulations and metabolite composition of rice plants. Moreover, this change directly affects the metabolite composition of rice seeds [6]. As a result, the difference of cultivation temperature between Korea and China is predicted to induce the divergence in the metabolomes of white rice.

Untargeted metabolomics is a comprehensive approach to investigate the metabolic responses of plants to environmental factors [7–9]. It can also reveal the relationship among metabolic networks because of its unbiased and exhaustive analysis of metabolites [10]. Common technologies such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) have been well established. GC–MS is suitable for the separation and detection of primary metabolites (amino acids, sugars & sugar alcohols) with high reproducibility of the retention index. In addition, this approach is strengthened by invaluable reference databases in which the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library is an excellent example. LC–MS, on the other hand, detects a wide range of analytes yet it is more appropriate to analyze secondary metabolites such as lipids, alkaloids, flavonoids, and glucosinolates, which represent the quality of plants regarding their nutritional values [7]. Above all else, compare with other spectroscopy techniques, such as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR), mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics has great advantages regarding the discrimination analysis and novel markers discovery with outstanding sensitivity and accuracy [8].

Although untargeted metabolomics for plant origin discrimination has been well established and thoroughly studied in previous studies [11–14], rice metabolomics, particularly the metabolite-based discrimination of white rice from different origins has received less attention. This fact comes from several reasons. First, white rice from the local markets is not rigidly controlled. Uncontrollable variables, such as pesticide, temperature, storage time, and storage conditions may affect the metabolite composition of white rice [15]. These uncontrolled variables may result in misleading conclusions of a particular analysis. However, if these uncontrollable variables are not included in the discrimination, the analytical method is not practical and cannot be applied to actual adulteration problems. Second, there is a serious metabolite loss because most nutrients are removed during the milling procedures [16]. It is of importance to mention that the amount of the metabolites is the most important element in untargeted metabolomics [17]. However, nutrients such as sugar, several amino acids, and lipids still remain in white rice [16], some of which are closely related to the starch and oligosaccharide metabolism [5]. Therefore, an evaluation of these compounds in search for potential markers, which surmount the constraints of white rice from different origins, should be meaningful.

In this study, novel markers for the discrimination of non-waxy type of white rice from Korea and China were established and compared. Thereafter, we estimated the discrimination efficiency of markers using several multivariate analyses. Using GC–MS and LC–MS, we identified both primary and secondary metabolites with the full-scan mode. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) analysis was conducted to develop discriminatory models and the variable importance in projection (VIP) score was employed to seek for the potential markers. The potential markers and classification efficiencies were also evaluated by using Random Forests (RF), a state-of-the-art supervised learning method. This study, therefore, suggests and evaluates the most potential markers that are responsible for the geographical differences, in which temperature is putatively considered as the main factor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, isopropanol, water, and chloroform were purchased from JT Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Formic acid, derivatizing reagent N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA), trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS), methoxyamine hydrochloride, and pyridine were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Information and preparation of white rice samples

White rice samples cultivated in 2014, 2015, and 2016 were purchased from the local markets of each country. Detailed information on all collected samples, which include the number of samples and cultivated places, is shown in Tables S1, S2 and S4. The collected samples were directly freeze-dried in the dark within two days after collecting and stored at −70 °C to avoid metabolite changes.

2.3. GC–MS experiment

2.3.1. Sample preparation

The extraction procedure was followed the optimal protocol as previously reported [18]. Before extraction with 1 mL of a chloroform:methanol:water (1:2.5:1) mixture, 1 mg of caffeine was added as the internal standard to each 200 mg of powdered samples. The extraction was conducted by sonication for 30 min at room temperature and the crude extract was centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 g. Then, 500 μL of the methanol/water phase was transferred to a 2 mL clear crimp vial (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and dried using a SpeedVac at 5000 g and 25 °C for 5 h. For derivatization, 80 μL of methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine (15 mg/mL) was added to each vial and incubated in a 30 °C oven for 90 min. Thereafter, 100 μL of BSTFA with 1% TMCS was mixed with the solution and kept in an oven at 60 °C for 15 min.

2.3.2. Instrument parameters

The GC–MS analysis was performed by using the Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 system. To separate the analytes, a DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm thick film) was utilized. The flow rate of the helium (carrier gas) was set to 1.0 mL/min. 1 μL of sample was injected using split-mode injection of 1:2 at 300 °C. The oven temperature gradient was initially set at 60 °C and maintained for 5 min; the temperature was increased linearly to 300 °C at a rate of 6 °C/min and held for 10 min. The ion source temperature was 200 °C, and the interface temperature was set to 300 °C. Electron-impact ionization was performed with an electron energy of 70 eV. The mass range was m/z 40–500. The sequence of sample analysis was randomized.

2.3.3. Data acquisition and processing

The acquired GC/MS data were exported to the .cdf format and preprocessed using MZmine 2.23 [19]. The Automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System (AMDIS) was then applied to group the fragment ions with the precursor ions of the mass spectra. The corresponding compounds were putatively identified using the NIST08 database and all the selected markers were finally confirmed using the authentic standards. All processed data were furthered scaled using Pareto scaling method prior to statistical and chemometric analysis.

2.4. LC–MS experiment

2.4.1. Sample preparation

Our previous experiment suggests that phospholipids maybe the potential markers for the discrimination of white rice between Korea and China [20]. Therefore, the validated extraction method was utilized to extract starch lipids from white rice as previously reported [21,22]. First, the dried white rice samples were pulverized; 150 mg was accurately weighed and mixed with 1 mg of caffeine as an internal standard. The mixture of samples was extracted with 8 mL of 75% isopropanol and sonicated for 2 h at 100 °C. The crude extract was centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 g, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) syringe filter.

2.4.2. Instrument parameters

The analysis was performed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent) equipped with an Acquity™ Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) column (BEH C18, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) and Agilent Q-ToF 6530 mass spectrometer (Agilent, USA). For each sample, 5 μL was injected and separated using the following gradient method with Solvent A (water + 0.1% formic acid) and Solvent B (acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid): 0 min 100% A; 5 min 70% A; 15 min 30% A; 25 min 20% A; ~27 min 0% A. The flow rate was set to 0.17 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. For the column equilibration, 10 min of equilibration time was applied among the sample injection. In direct infusion (DI)-based experiment, with the column removed,50% Awith 0.2 mL/ min of flow rate was set during analysis to avoid the damage of the ion source. Mass spectrometry was performed in the ESI negative ion mode. The mass range was set to m/z 50–1500. The lock mass was injected together with every sample to maintain the accuracy of the m/z value. For structure elucidation of identified markers, additional collision energy condition, 20 eV, was applied. For the validation of the proposed panel of discrimination markers, LC- and DI-multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)-based targeted experiment utilizing Agilent Triple Quadrupole (QqQ) 6460 system (Agilent, USA) were conducted. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared and relative standard deviations (RSDs) were calculated. The validation experiment was conducted using different and non-overlapping white rice samples from Korea and China. Similar to the GC–MS experiment, the randomized sequence was used for every analysis.

2.4.3. Data acquisition and processing

All LC–MS data were converted to the mzdata format. Data preprocessing was performed using MZmine 2.23. Fragment ions were gathered with the corresponding precursor ions. Precursor ions of the metabolites were identified by their fragmentation patterns using the authentic standards, MET-LIN metabolite database (http://metlin.scripps.edu/), published references, and our in-house database [23]. Similar to GC–MS preprocessing strategy, all LC–MS processed data were furthered scaled using Pareto scaling method prior to statistical and chemometric analysis. DI-MS data was extracted and proceeded as previously described [20,24,25].

2.5. Statistical and chemometric analysis

Pareto-scaled data were subjective to the analysis. All statistical, unsupervised learning, and supervised learning analyses were performed using the web-based metabolomics data processing tool MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) [26].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Multivariate statistical analysis of the untargeted metabolomics results and the screening of discrimination marker signatures

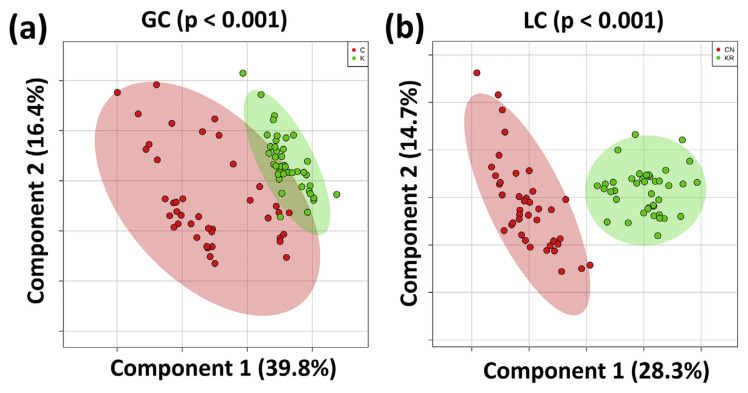

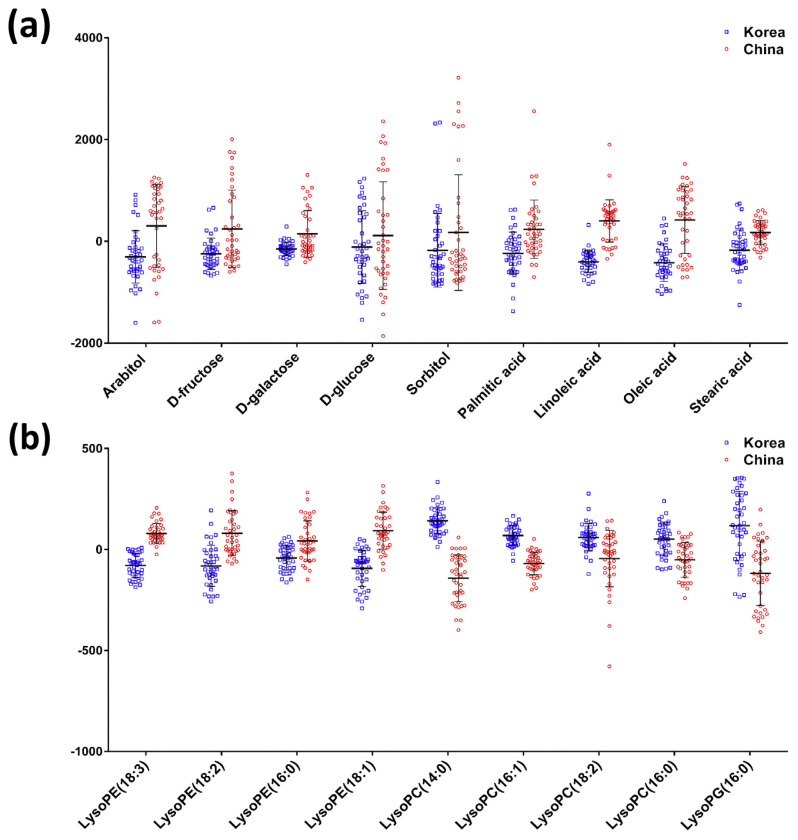

Eighty samples of white rice from Korean and Chinese local markets were analyzed with GC–MS and LC–MS approaches. After data preprocessing and normalization, 69 and 53 features were identified in the GC–MS and LC–MS untargeted experiments, respectively. Among them, the concentrations of 28 features were found to be significantly different between two groups (p-value < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05). Thereafter, PLS-DA with cross-validation and 1000-time permutation test were applied to determine whether the samples could be differentiated [10]. To detect potential markers, we obtained the VIP scores from component 1 to evaluate the importance of the features in the discrimination model. The features with VIP score larger than 0.8 and were significantly different in the univariate analysis were considered to be the marker candidates. Based on this criterion, 20 features were found to be the potential markers (11 from GC–MS and nine from LC–MS). Three were considered to be monosaccharides, two were sugar alcohols, four were fatty acids, and nine metabolites were phospholipids (PLs). The detailed information is listed in Table 1 (GC–MS) and Table 2 (LC–MS). Sugars, sugar alcohols, and fatty acids derived from GC–MS were confirmed by the NIST08 library and the authentic standards. Eventually, d-fructose, d-galactose, d-glucose, arabitol, sorbitol, palmitic acid, linoleic acid, oleic acid, and stearic acid were confirmed. The markers of LC–MS experiment were regarded as PLs by their precise m/z. For identification, targeted MS/MS analysis was further applied for generating unique fragmentation patterns of specific PL species [27]. With the m/z value of the precursor ions and the fragmentation patterns at the collision energy of 20 eV, four metabolites matched the lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LysoPE) spectra. They were confirmed to be LysoPE(18:3), LysoPE(18:2), LysoPE(16:0), and LysoPE(18:1). Another four markers were corresponded with lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC) spectra and identified as LysoPC(14:0), LysoPC(16:1), LysoPC(18:2), and LysoPC(16:0). One marker was consistent with the spectrum of lysophosphatidylglycerol (LysoPG) and turned out to be LysoPG(16:0). The fragmentation patterns with structure elucidation of LysoPEs, LysoPCs, and LysoPG were listed in Fig. S1. Consequently, except d-glucose, sorbitol, stearic acid, and LysoPE(16:0), other markers generally showed a relative small p-value and FDR, which implies that they are the significantly different features between two groups of white rice. Of note, the significant level does not necessarily indicate the impact of the candidates [28]. In terms of the discrimination efficiency, the high accuracy, goodness-of-fit (R2), and goodness-of-prediction (Q2) values of the constructed models guaranteed that good classifications to discriminate white rice samples from different countries were achieved in both (a) GC–MS (accuracy = 0.950, R2 = 0.824, Q2 = 0.753), and (b) LC–MS (accuracy = 1.000, R2 = 0.972, Q2 = 0.894) (Fig. 1). For visualizing the relative levels of discrimination markers from white rice of Korea and China, box plots were used. According to the mean value, sugars & sugar alcohols, fatty acids, and LysoPEs showed a higher level in Chinese white rice. Meanwhile, LysoPCs and LysoPG showed higher concentration in Korean white rice (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The characteristics of GC–MS-based discrimination markers.

| Identification | Retention time | Chemical formula | NIST | VIP | t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Match | Score | p-value | FDR | |||

| Propionic acid | 7.81 | C3H6O2 | 973 | 0.807 | 5.647E-5 | <0.001 |

| Oxalic acid | 9.63 | C3H2O4 | 917 | 0.934 | 7.051E-9 | <0.001 |

| Arabitol | 21.92 | C5H12O5 | 937 | 1.519 | 6.939E-4 | 0.002 |

| d-fructose | 24.52 | C6H12O6 | 976 | 1.624 | 8.595E-6 | <0.001 |

| d-galactose | 24.84 | C6H12O6 | 941 | 0.914 | 2.238E-5 | <0.001 |

| d-glucose | 24.90 | C6H12O6 | 939 | 1.151 | 3.923E-2 | 0.048 |

| Sorbitol | 25.50 | C6H12O6 | 936 | 1.116 | 3.134E-2 | 0.007 |

| Palmitic acid | 27.55 | C16H32O2 | 938 | 1.468 | 8.731E-8 | <0.001 |

| Linoleic acid | 30.06 | C18H32O2 | 936 | 1.723 | 1.101E-9 | <0.001 |

| Oleic acid | 30.16 | C18H34O2 | 932 | 1.802 | 4.153E-9 | <0.001 |

| Stearic acid | 30.54 | C18H36O2 | 920 | 1.219 | 1.030E-2 | 0.018 |

Table 2.

The characteristics of LC–MS-based discrimination markers.

| Identification | Retention time | Mass per charge ratio (m/z) | Chemical formula | VIP | t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Measured | Exact | Adduct ion | Score | p-value | FDR | |||

| LysoPE(18:3) | 12.86 | 474.261 | 474.262 | [M−H]− | C23H41NO7P | 1.777 | 8.607E-9 | <0.001 |

| LysoPE(18:2) | 13.56 | 476.277 | 476.278 | [M−H]− | C23H43NO7P | 1.435 | 1.801E-3 | 0.006 |

| LysoPE(16:0) | 14.29 | 452.279 | 452.278 | [M−H]− | C21H43NO7P | 0.927 | 1.879E-2 | 0.031 |

| LysoPE(18:1)a | 14.58 | 478.294 | 478.293 | [M−H]− | C23H45NO7P | 1.478 | 1.292E-3 | 0.004 |

| LysoPC(14:0)a | 12.85 | 512.300 | 512.299 | [M−H + HCOOH]− | C23H47NO9P | 3.454 | 2.762E-13 | <0.001 |

| LysoPC(16:1) | 13.11 | 538.314 | 538.315 | [M−H + HCOOH]− | C25H49NO9P | 1.416 | 1.501E-7 | <0.001 |

| LysoPC(18:2) | 13.70 | 564.332 | 564.330 | [M−H + HCOOH]− | C27H51NO9P | 1.411 | 7.177E-3 | 0.018 |

| LysoPC(16:0) | 14.34 | 540.330 | 540.330 | [M−H + HCOOH]− | C25H51NO9P | 1.167 | 4.086E-4 | 0.002 |

| LysoPG(16:0)a | 16.22 | 483.271 | 483.272 | [M−H]− | C22H44O9P | 2.464 | 3.823E-4 | 0.001 |

These compounds were identified by authentic standards.

Fig. 1.

Untargeted GC–MS-based and untargeted LC–MS-based PLS-DA models reveal good potential for discriminating white rice samples between Korea and China. (a) The accuracy, goodness-of-fit, and goodness-of-prediction of untargeted GC–MS-based PLS-DA were 0.931, 0.750, and 0.692 respectively. (b) The accuracy, goodness-of-fit, and goodness-of-prediction of untargeted LC–MS-based PLS-DA were 0.987, 0.972, and 0.889 respectively.

Fig. 2.

The box plots that show the differential concentrations among selected discrimination markers. (a) The relative concentrations of sugars & sugar alcohols and fatty acids. (b) The relative concentrations of phospholipids.

3.2. Evaluation of the efficiency of potential marker groups

From our previous study, lysoPLs are shown to be effective in discriminating the origins of non-waxy white rice [24,25]. However, it is unclear about the potential of other groups of biomarkers. Based on the above selection approach for potential markers from both GC–MS and LC–MS experiments, we evaluated which compound group was more reliable and efficient for origin discrimination. Therefore, the potential marker candidates from the untargeted metabolomics analyses were grouped into (1) sugars & sugar alcohols, (2) fatty acids, and (3) PLs. Then, the discrimination ability of each group was evaluated by various multivariate analyses. Principal component analysis (PCA) and heatmap were conducted for data exploration and visualization. Unsupervised k-means clustering with the predefined group number of two was also conducted to observe the grouping tendency of white rice samples. After that, PLS-DA was proceeded to examine the reliability, significance, and superiority of the differently constructed discrimination models. Additionally, RF classifier was also applied to test for the classification accuracy of each marker group. With these analyses, we investigated which group had the best accuracy to discriminate white rice from two different origins.

3.2.1. Principal component analysis (PCA)

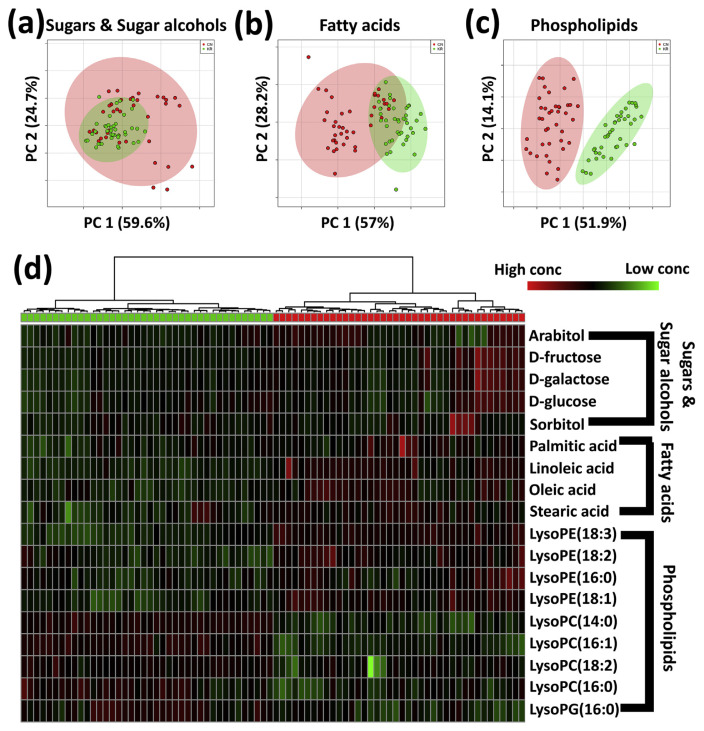

As the most famous multivariate statistical tool, PCA is an unsupervised method to explore the sample variance in a dataset without referring to the class label and suggest predictive abilities of the later supervised learning models. In PCA, the original variables are summarized into significantly fewer variables using their profiles [29]. To compare the grouping efficiency of potential candidate markers, we applied PCA to each group of discrimination markers. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Results show that the PLs account for the completely clear grouping tendencies, and the sugars & sugar alcohols show the worst discrimination tendency for two different origins of white rice.

Fig. 3.

The PCA score plots and heatmap of sugars & sugar alcohols, fatty acids, and phospholipids. (a) The PCA score plot of sugars & sugar alcohols, (b) The PCA score plot of fatty acids, (c) The PCA score plot of phospholipids, (d) The heatmap visualization of selected discrimination markers.

3.2.2. Heatmap

Potential markers were constructed to visualize the clusterization based on Euclidean distance measurement with Ward clustering algorithm. According to the relative amounts of markers in two datasets, the heat map used the average linkage algorithm with correlation distance and classified the samples into each group [30]. The markers in sugars & sugar alcohols groups exhibited the poorest difference between two groups of white rice; even in the same origin, the variations of each marker were immoderate, especially in white rice from China. The markers in fatty acids cluster, on the other hand, showed a relatively clear discrimination result. However, the cluster which expressed the most outstanding discrimination capabilities was the PLs cluster (Fig. 3-(d)).

3.2.3. k-means clustering

The k-means clustering has become a widely used clustering approach of transcriptomic studies in recent years. However, it is relatively new to other Omics fields, particularly metabolomics [31]. In k-means clustering, the number of clusters should be decided prior to the analysis and then the algorithm will randomly choose the centers and training sets for the iterative clustering. The process will proceed until the cluster centers and the classified groups are no longer changed. As shown in Fig. S2, the 2-clusters of white rice samples generated from sugars & sugar alcohols and fatty acids were poor that contained many mislabeling samples. On the other hand, nine PL discrimination marker set showed two distinct clusters of white rice between Korea and China without any mismatch. This result once again supported the idea of selecting PLs as novel markers for geographical discrimination of white rice.

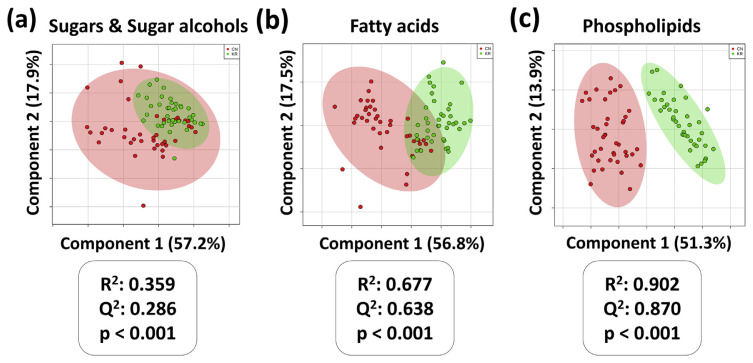

3.2.4. Subgroup PLS-DA models with cross-validation and permutation test

As every classification needs strictly validation, cross-validation is currently the method of choice measure the predictive performance and challenge the reliability of a classification model with limited samples [10]. Our study applied the 10-fold cross-validation (10-fold CV) and permutation test to estimate the performance of the PLS-DA models. The R2 and Q2 values of the cross-validation as well as permutation test p-values of the corresponding models are shown in Fig. 4. The model generated by PLs panel indicates the best performance (R2 = 0.902, Q2 = 0.870, and p-value < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

PLS-DA with cross validation and permutation test results of sugars & sugar alcohols, fatty acids, and phospholipids.

3.2.5. Subgroup Random Forests (RF) classification models

In metabolomics, discrimination procedure using various statistical methods is important [32]. RF is a powerful and well established classifier and it is relatively new in metabolomics [33]. Because a single decision tree is a week classification model, the RF combines many decision trees and provides an accurate classification result [34]. The advantages of RF include the following: (1) notably high classification accuracy, (2) new method to determine the variable importance, (3) the ability to model various non-linear interactions among predictor variables, and (4) consistent with outliers and missing values [33]. In this study, we focused on the classification accuracy and ability to model the complex interaction among the predictor variables. Regarding the number of potential markers from each group, 500 trees were sufficient, and the number of predictors of each node was set to seven. As shown in Fig. S3, PLs panel had an excellent classification ability indicated by minimized the classification error (two errors in Chinese white rice, which accounted for 5% and only one error in Korean white rice, 2.5%). The RF classification using fatty acids also exhibited a good accuracy (two errors in Chinese white rice, 5% and four errors in Korean white rice, 10%). The classification of sugars & sugar alcohols showed poor accuracy since the class errors of white rice from Korea and China were 22.5% and 20%, respectively.

3.2.6. The assessment and validation of PL discrimination panel using MRM-MS-based approaches

In order to verify the PLs as efficient discrimination markers, LC-MRM-based targeted analysis was performed using nine identified PLs in new white rice samples. Twenty additional samples, 10 versus 10, share similar properties with the analyzed samples of the discovery stage (Table S2). QC samples were also prepared to evaluate RSDs. All target components including the internal standard, caffeine, showed excellent RSDs, which were lower than 10% (Table S3). The accuracy, R2, and Q2 of LC-MRM-based PLS-DA were 1.000, 0.913, and 0.886 with p-value of permutation test was lower than 0.001 (Fig. S4). Concentration differences between two groups through box plot also showed the similar tendency with preceded experiments (Fig. S5). Furthermore, the RF also showed excellent classification results, which can be seen in Fig. S6.

To measure the reproducibility of the PLs panel, we performed DI-MRM-MS targeted lipidomics approach using 2016 white rice sample from both countries (10 vs 10, Table S4). RSD of every target compounds were lower than 10% (Table S5). As shown in Fig. S7, DI-MRM-based PLS-DA shows an excellent performance (accuracy = 1.000, R2 = 0.940, Q2 = 0.906, and p-value < 0.001). The box plots show similar tendency in terms of the lysoPLs' concentrations (Fig. S8). Likewise, the remarkable classification using RF can be seen in Fig. S9. Collectively, the validation experiments using new white rice samples revealed the robustness of the nine PL discrimination markers.

3.2.7. The most efficient discrimination markers in the current study

Collectively, the above results demonstrated the discrimination accuracy of selected PLs markers with high reliability in terms of the remarkable consistency, minor fluctuation, and low error classification rate in cross-validation. Therefore, PL discrimination marker signature, which include LysoPE(18:3), LysoPE(18:2), LysoPE(16:0), LysoPE(18:1), LysoPC(14:0), LysoPC(16:1), LysoPC(18:2), LysoPC(16:0), and LysoPG(16:0) can be considered as the best discrimination markers for white rice between Korea and China in this study. The biological functions of PLs and the association between amylose and starch lipids are briefly discussed in supporting materials. Our study has several limitations that have to be mentioned. First, there is no quantitative analysis to estimate the actual concentration of each component identified by GC–MS and LC–MS experiments. Second, the current study focused on the comparison of three identified groups of biomarkers regarding their performances in geographical discrimination of non-waxy commercial white rice. There is no investigation of waxy rice. Further studies are required to examine those gaps as well as extend our findings for the screening of adulterated white rice.

4. Conclusion

Robust discrimination markers for the authentication of white rice from different geographical origins are crucial. In this study, potential markers were proposed and compared using an untargeted metabolomics approach combined with current state-of-the-art multivariate methods. Twenty metabolites were initially found to be the potential markers categorized into sugars & sugar alcohols, fatty acids, and phospholipids. Further examinations suggested the remarkable performance of phospholipids over fatty acids and sugars & sugar alcohols as the discrimination markers. In conclusion, our proposed phospholipid-based discrimination panel may improve the reliability of the discrimination analysis of white rice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Rural Development Administration of Korea (PJ01164601), the Bio-Synergy Research Project of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation (NRF-2012M3A9C4048796), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2009-0083533).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2017.09.004.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Rural Development Administration of Korea (PJ01164601), the Bio-Synergy Research Project of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation (NRF-2012M3A9C4048796), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2009-0083533).

References

- 1. Fitzgerald MA, McCouch SR, Hall RD. Not just a grain of rice: the quest for quality. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu L, Waters DL, Rose TJ, Bao J, King GJ. Phospholipids in rice: significance in grain quality and health benefits: a review. Food Chem. 2013;139:1133–45. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao W, Chung J-W, Ma K-H, Kim T-S, Kim S-M, Shin D-I, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of rice cultivars from Korea, China and Japan using SSR markers. Genes Genom. 2009;31:283–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akula R, Ravishankar GA. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:1720–31. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.11.17613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Obata T, Fernie AR. The use of metabolomics to dissect plant responses to abiotic stresses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:3225–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zakaria S, Matsuda T, Tajima S, Nitta Y. Effect of high temperature at ripening stage on the reserve accumulation in seed in some rice cultivars. Plant Prod Sci. 2015;5:160–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee DK, Yoon MH, Kang YP, Yu J, Park JH, Lee J, et al. Comparison of primary and secondary metabolites for suitability to discriminate the origins of Schisandra chinensis by GC/MS and LC/MS. Food Chem. 2013;141:3931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Vos RC, Moco S, Lommen A, Keurentjes JJ, Bino RJ, Hall RD. Untargeted large-scale plant metabolomics using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:778–91. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diaz R, Pozo OJ, Sancho JV, Hernandez F. Metabolomic approaches for orange origin discrimination by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014;157:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim S, Shin B-K, Lim DK, Yang T-J, Lim J, Park JH, et al. Expeditious discrimination of four species of the Panax genus using direct infusion-MS/MS combined with multivariate statistical analysis. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2015;1002:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi M-Y, Choi W, Park JH, Lim J, Kwon SW. Determination of coffee origins by integrated metabolomic approach of combining multiple analytical data. Food Chem. 2010;121:1260–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomita S, Nemoto T, Matsuo Y, Shoji T, Tanaka F, Nakagawa H, et al. A NMR-based, non-targeted multistep metabolic profiling revealed L-rhamnitol as a metabolite that characterised apples from different geographic origins. Food Chem. 2015;174:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nguyen HT, Min J-E, Long NP, Thanh MC, Van Le TH, Lee J, et al. Multi-platform metabolomics and a genetic approach support the authentication of agarwood produced by Aquilaria crassna and Aquilaria malaccensis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;142:136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu D, He J, Jiang Y, Yang B. Quality analysis of Polygala tenuifolia root by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitter AH, Hay RK. Environmental physiology of plants. Academic press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slavin JL, Jacobs D, Marquart L. Grain processing and nutrition. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2001;21:49–66. doi: 10.1080/20013891081683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lommen A. MetAlign: interface-driven, versatile metabolomics tool for hyphenated full-scan mass spectrometry data preprocessing. Anal Chem. 2009;81:3079–86. doi: 10.1021/ac900036d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JK, Bamba T, Harada K, Fukusaki E, Kobayashi A. Time-course metabolic profiling in Arabidopsis thaliana cell cultures after salt stress treatment. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:415–24. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pluskal T, Castillo S, Villar-Briones A, Orešič M. MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim DK, Mo C, Long NP, Kim G, Kwon SW. Simultaneous profiling of lysoglycerophospholipids in rice (Oryza sativa L.) using direct infusion-tandem mass spectrometry with multiple reaction monitoring. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:2628–34. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu L, Tong C, Bao J, Waters DL, Rose TJ, King GJ. Determination of starch lysophospholipids in rice using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:6600–7. doi: 10.1021/jf500585j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim DK, Long NP, Mo C, Dong Z, Lim J, Kwon SW. Optimized mass spectrometry-based metabolite extraction and analysis for the geographical discrimination of white rice (Oryza sativa L.): a method comparison study. J AOAC Int. 2017;101:2. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith CA, O'Maille G, Want EJ, Qin C, Trauger SA, Brandon TR, et al. A metabolite mass spectral database. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27:747–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000179845.53213.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lim DK, Long NP, Mo C, Dong Z, Cui L, Kim G, et al. Combination of mass spectrometry-based targeted lipidomics and supervised machine learning algorithms in detecting adulterated admixtures of white rice. Food Res Int. 2017;100:814–21. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Long NP, Lim DK, Mo C, Kim G, Kwon SW. Development and assessment of a lysophospholipid-based deep learning model to discriminate geographical origins of white rice. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08892-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0—making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fang J, Barcelona MJ. Structural determination and quantitative analysis of bacterial phospholipids using liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry. J Microbiol Methods. 1998;33:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xi B, Gu H, Baniasadi H, Raftery D. Statistical analysis and modeling of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1198:333–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1258-2_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W652–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao Y, Zhao C, Li Y, Chang Y, Zhang J, Zeng Z, et al. Study of metabolite differences of flue-cured tobacco from different regions using a pseudotargeted gas chromatography with mass spectrometry selected-ion monitoring method. J Sep Sci. 2014;37:2177–84. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201400097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindon JC, Nicholson JK, Holmes E. The handbook of metabonomics and metabolomics. Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beckmann M, Enot DP, Overy DP, Draper J. Representation, comparison, and interpretation of metabolome fingerprint data for total composition analysis and quality trait investigation in potato cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3444–51. doi: 10.1021/jf0701842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cutler DR, Edwards TC, Jr, Beard KH, Cutler A, Hess KT, Gibson J, et al. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology. 2007;88:2783–92. doi: 10.1890/07-0539.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kingsford C, Salzberg SL. What are decision trees? Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1011–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt0908-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]