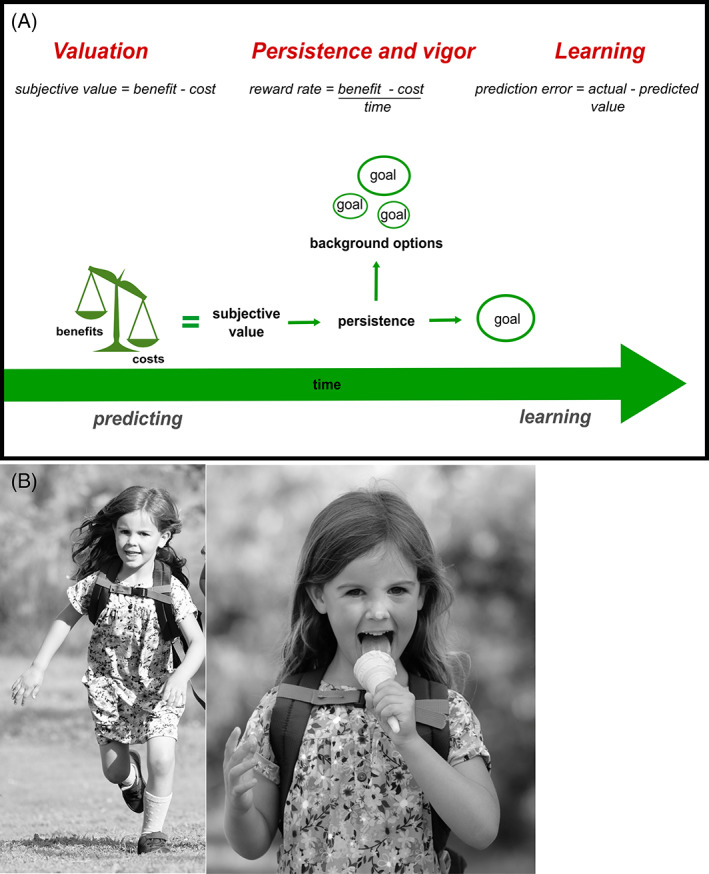

FIG 1.

A cognitive framework for goal‐directed behavior. (A) Three distinct phases of cost‐benefit decision‐making (in red above) lie at the heart of the pursuit (or not) of a rewarding goal. Initially, predictions are made about the values of rewards associated with a goal and the costs that will be incurred to reach it. After behavioral activation, continued invigoration and persistence are required to attain the goal. However, an alternate option in the environment may have a higher value, in which case a behavioral switch away from the original goal may be optimal. After goal attainment (or failure of attainment), the experienced rewards and costs are compared with the predicted ones in a learning process that modifies future behavioral choices. Disruption to any of these inter‐related cognitive processes will alter goal‐directed behavior and can manifest behaviorally as apathy and/or impulsivity. (B) A real‐world example of goal‐directed behavior: a child decides it is worth undertaking a long (effortful) walk in return for a promised ice cream cone (reward) at the end. She must then persist with her effortful response, over time, to attain the goal. Concurrently, she evaluates the value of alternatives in her environment: if an ice cream stall was to present itself around the next corner, her initial goal may no longer be worth it. After completing the walk, and receiving her ice cream, she compares these actual costs and rewards with those she predicted at the beginning of the walk. Any difference in these values drives learning, which will inform her future decisions. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]