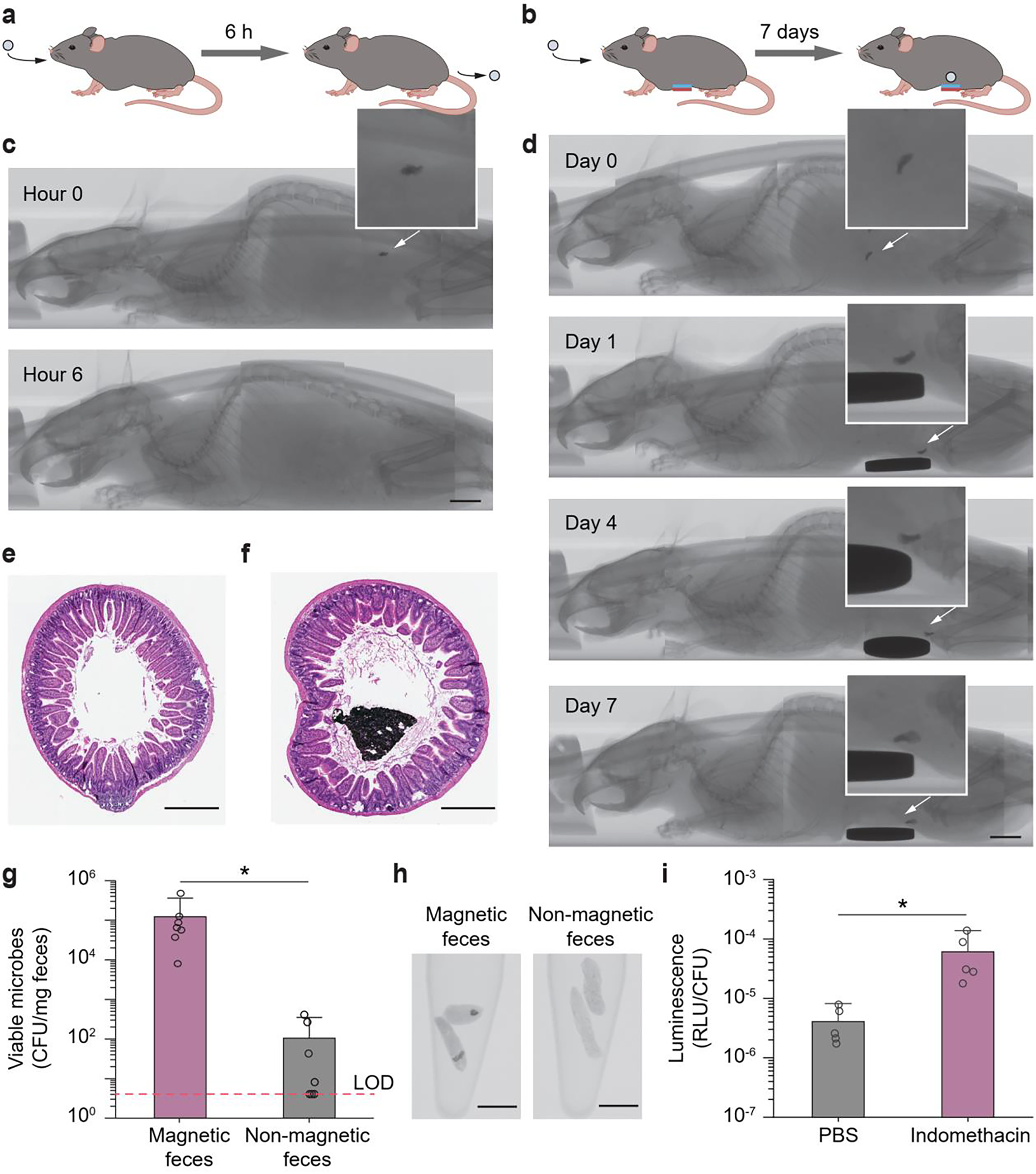

Figure 5.

In vivo validation of magnet-assisted retention and in vivo heme sensing function of the magnetic living hydrogels. a) Illustration of an ingested magnetic living hydrogel passing through the whole GI tract of a mouse within ~ 6 h. b) Illustration of an ingested magnetic living hydrogel retained in the GI tract of a mouse for 7 days by an external magnet attached to the abdomen. c) CT images of a mouse with an ingested magnetic living hydrogel passing through the whole GI tract of a mouse within ~ 6 h. d) CT images of a mouse with an ingested magnetic living hydrogel retained in its intestine for 7 days by an extracorporeal magnet attached on the abdomen. Scale bars in c-d: 5 mm. e-f) Representative histological images stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for assessment of the small intestine cross-section without (e) and with (f) a magnetic hydrogel after 7-day intestinal retention. Scale bars: 500 μm. g) Numbers of viable microbes in fecal pellets collected from mice at 12 h post-administration of the hydrogel (containing blood-sensing E. coli Nissle 1917). The fecal samples with and without magnetic hydrogels exhibit significant differences in microbe numbers (*P < 0.05; Student’s t test; n = 7). Dashed line indicates the limit of detection (LOD) of the assay. h) CT images of fecal pellets with or without magnetic hydrogels. Scale bars: 5 mm. i) In vivo blood sensing performance. After the magnetic hydrogel (containing blood-sensing E. coli Nissle 1917) was retained in the intestine, mice were administered indomethacin (to induce gastrointestinal bleeding) or PBS. Normalized luminescence values of fecal pellets 24 h post-induction are significantly higher in mice administered indomethacin compared to control animals (*P < 0.05; Student’s t test; n = 5). RLU, relative luminescence units.