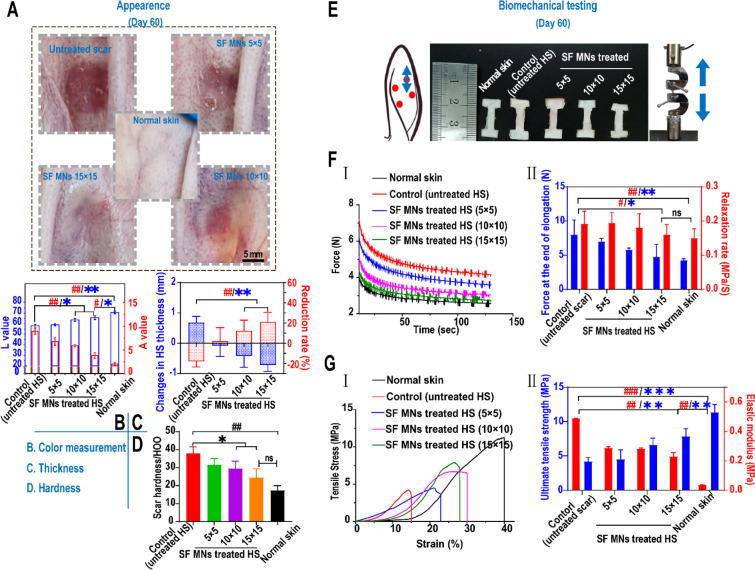

Figure 4.

In vivo treatment of rabbit ear hypertrophic scars with SF MN patches. (A) Appearances of post-treated scar tissues. Scale bar, 5 mm. (B) Color measurement of scars post-treatment. A higher value of L represents a whiter color, and a higher value of A represents a redder color. **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 represent significant differences in L values; ##p < 0.01 represents significant differences in A value, n = 3. (C) Changes in thickness of scar tissues before and post-treatment. **p < 0.01 represents significant differences in changes in thickness (mm); ##p < 0.01 represents significant differences in the reduction rate of thickness (%), n = 3. (D) Hardness of scars post-treatment. ##p < 0.01 compared with the normal dermis,; *p < 0.05 compared with the control group, n = 3. (E) Dumbbell-shaped mechanical test specimens of uninjured skin and scars in the direction of the axial axis for the uniaxial stress relaxation and tensile failure testing. (F) In stress relaxation experiments, two measurements, including peak relaxation load and relaxation rate (II), were calculated from the elongation–relaxation data (I). #p < 0.05 represents a significant difference in the rate of relaxation; *p < 0.05 represents a significant difference in peak load, n = 3. (G) Tensile failure experiments. Two measurements, including the ultimate tensile stress and elastic modulus (II), were calculated from stress–strain data (I). ###p < 0.001 and ##p < 0.01 represent significant differences in elastic modulus; ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01 represent significant differences in ultimate tensile stress, n = 3.