Abstract

Arid and semi-arid areas are considered vulnerable to various environmental constraints which are further fortified by climate change. Salinity is one of the most serious abiotic factors affecting crop yield and soil fertility. Till now, no information is available on the effect of salinity on development and symbiotic nitrogen (N2) fixation in the legume species Lathyrus cicera. Here, we evaluated the effect of different microbial inocula including nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium laguerreae, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF) Rhizophagus irregularis, a complex mixed inoculum of AMF isolated from rhizospheric soil in “Al Aitha”, and various plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) including Bacillus subtilus, Bacillus simplex and Bacillus megaterium combined with Rhizobium, the AMF consortium, or R. irregularis on alleviating salt stress in this legume. A pot trial was conducted to evaluate the ability of different microbial inocula to mitigate adverse effects of salinity on L. cicera plants. The results showed that salinity (100 mM NaCl) significantly reduced L. cicera plant growth. However, inoculation with different inocula enhanced plant growth and markedly promoted various biochemical traits. Moreover, the combined use of PGPB and AMF was found to be the most effective treatment in mitigating deleterious effects of salinity stress on L. cicera. In addition, this co-inoculation upregulated the expression of two marker genes (LcHKT1 and LcNHX7) related to salinity tolerance. Our findings suggest that the AMF/PGPB formulation has a great potential to be used as a biofertilizer to improve L. cicera plant growth and productivity under saline conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-022-01205-4.

Keywords: L. cicera, PGPB, Salinity, Gene expression, AMF consortium

Introduction

The legume species Lathyrus cicera (red pea) is a valuable crop for the fertilization of soils by nitrogen fixation in root nodules (Gritli et al. 2020). In addition, it is economically important as feed for poultry, pigs, and sheep. L. cicera is also used for forage and green manure (White et al. 2012; Siddique et al. 2012; Patto and Rubiales 2014). Furthermore, it contains high amounts of biologically active compounds such as phenolics that can serve as food additives in the food industry (Ferreres et al. 2017). Global food demand is expected to double by 2050 (Hatfield and Charles 2015). In order to fulfill this demand, there is an urgent need to learn how to increase crop yield, especially under environmental constraints. Salinity is one of the most serious abiotic factors affecting crop yield and soil fertility. Soil salinity is increasing steadily in many parts of the world at a rate of 10% per year for various reasons, such as low precipitation, evaporation and poor cultural practices, and it is estimated that more than 50% of arable land would be salinized by 2050 (Jamil et al. 2011). Lathyrus species were found to be highly tolerant against abiotic stresses (Patto et al. 2006). Furthermore, seeds of L. cicera are a cheap source of proteins and other nutrients, with very low content of the neurotoxin 3-N-oxalyl)-L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (ODAP) (0.09–0.49%) (Hanbury et al. 2000). This legume species contains also a high amount of biologically active compounds such as natural antioxidants and enzyme inhibitors that can serve as food additives in food industry (Llorent-Martínez et al. 2017). These particular advantages make it a good candidate to face these enormous agricultural challenges (Patto and Rubiales. 2014). In Tunisia, about 50% of the total irrigated area is considered highly sensitive to salinization due to high evaporation, aridity, irrigation, and poor water management (Bouksila 2013). Salt stress limits plant growth by inducing osmotic stress resulting from a reduced water-availability and ion toxicity caused by nutrient imbalances (Flowers and Colmer 2008). In addition, salinity induces an accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), known to have deleterious effects on plant cells (Chakraborty et al. 2016). Root–associated microorganisms were reported to play an important role in promoting the biological state of saline soils. Rhizobia are important soil bacteria that engage in root nodule symbiosis (RNS), in which atmospheric nitrogen is converted to ammonia for the legume host. Apart from improved nitrogen (N) nutrition, RNS can promote the overall health of plants leading to enhanced stress tolerance. Previous reports have described the ability of different rhizobial strains in promoting plant growth under abiotic stress situations (Mhadhbi et al. 2011; El-Akhal et al. 2013; Irshad et al. 2021). The antioxidant enzymatic system was found to be crucial in salinity tolerance mechanisms (Bianco and Defez 2009; Mhadhbi et al. 2011). Moreover, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) amendment was found to increase the availability of phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N) and organic matter contents, thereby enhancing the plant nutrient acquisition (Wang et al. 2019; Qiu et al. 2020). Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis can also alleviate the adverse effects of salinity in different plant species by increasing plant nutrient uptake, the adjustment of osmotic potential and ion imbalance (Caravaca et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2007; Zhu et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2018). On the other hand, plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas and Enterobacter demonstrated their ability to improve crop productivity under arid and semi-arid conditions, as well as under salinity stress (Sharma et al. 2016; Sarkar et al. 2018; Niu et al. 2018).

Salinity tolerance of plants can be enhanced by combining AMF and PGPB treatments (Feng et al. 2002; Evelin et al. 2012; Younesi and Moradi 2014; Motaleb et al. 2020). For L. cicera, the beneficial effects of combining rhizobacteria (Rhizobia and endophytic bacteria) and AMF on salt stress tolerance have not been explored. The present study aimed to explore the potential of nitrogen-fixing bacteria (R. laguerreae), AMF, and PGPB inoculations on alleviating salinity stress in L. cicera. In addition to growth parameters, we monitored different biochemical traits such as proline and sugar contents, as well as antioxidant enzyme activities. Moreover, the expression pattern of two salt stress-related genes (HKT1 and NHX7) was investigated to better understand the mechanisms underpinning salinity tolerance mediated by root–associated microorganisms. Our data revealed the efficiency of combining AMF and PGPB treatments in reducing deleterious effects of salinity stress in L. cicera.

Materials and Methods

Inoculation procedure of red pea and culture conditions

Seeds of L. cicera (Zarzis accession) were sterilized with sodium hypochlorite (10% w/v) for 2 min, washed three times in sterile demineralized water, before germination on Petri plates containing moist filter paper at 25 °C for 96 h under dark conditions. Seedlings were individually transferred to 416 cm3 plastic pots (8 × 5 × 8 cm) containing unfertilized soil, that had been sterilized by incubation at 90 °C for 3 h with vapor. The different inoculation treatments are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Microbial inoculations applied in this study

| Treatments | Species | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uninoculated | No microbes |

| 2 | Rh | R. laguerreae (LS 1.6) |

| 3 | Rh/PGPB consortia |

R. laguerreae (LS 1.6) B. simplex (LC 2.3) B. subtilis (LC 3.5) B. megaterium (LC 5.2) |

| 4 | RI | R. irregularis MUCL 43,204 |

| 5 | RI/PGPB consortia |

R. irregularis MUCL 43,204 B. simplex (LC 2.3) B. subtilis (LC 3.5) B. megaterium (LC 5.2) |

| 6 | AMF consortium | AMF species as detailed in Fig. 1 |

| 7 | AMF/PGPB consortia |

AMF species as detailed in Fig. 1 B. simplex (LC 2.3) B. subtilis (LC 3.5) B. megaterium (LC 5.2) |

The rhizobium strain (LS 1.6) (Figure S1) was isolated from nodules of L. cicera roots and identified as R. laguerreae (Gritli et al. 2020). A pure colony of R. laguerreae was cultured in Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of YEM (Yeast Extract Mannitol) media. The liquid culture was incubated on a rotary shaker maintained at 150 rpm at 28 °C. 48 h later, 1 ml (nearly 109 CFUml−1) of the suspension culture was used for the inoculation of L. cicera plantlets. Luria Bertani broth medium was used to culture the different PGPB strains (Figure S1) separately by incubation for 24 h at 28 °C in a rotary shaker and 1 ml of each bacterial suspension (109 CFUml−1) was used for the inoculation. The AM fungus R. irregularis (MUCL 43,204) (Figure S2) was cultured on leek (department of biology, Fribourg, Switzerland). Inoculum potential was verified microscopically by assessing spore content, and one teaspoon (ca. 10 g) was used for inoculation. Spores of AM fungal consortia were extracted from the soil in the north of Tunisia and multiplied in corn. The AMF consortium used in the present work was subjected to molecular characterization by using Illumina MiSeq. AMF species identified are mentioned in Fig. 1. Inoculated L. cicera plantlets were grown in a greenhouse under controlled conditions (16/8 h photoperiod, 20 °C /25 °C temperature and 65% of relative humidity) from transplanting to the beginning of the application of salt treatment (3 weeks later). All the plants were watered twice per week with sterilized distilated water and, once per week, with the nutrient solution as previously described by Vadez et al (1996) (Table S1). Plants inoculated with rhizobium were watered with sterile nitrogen-free nutrient solution (Vadez et al. 1996). Thereafter, plants were either subjected or not to salt stress (100 mM NaCl), and five replicate plants were used for each treatment. The experiment was stopped 10 days later when the first plants showed clear stress symptoms (chlorosis). Three biological replicates were performed and each replicate consisted of three individual plants for the determination of shoot fresh weight (total aerial part). Then, the plant material was stored at −80 °C for enzyme assays and RNA extraction.

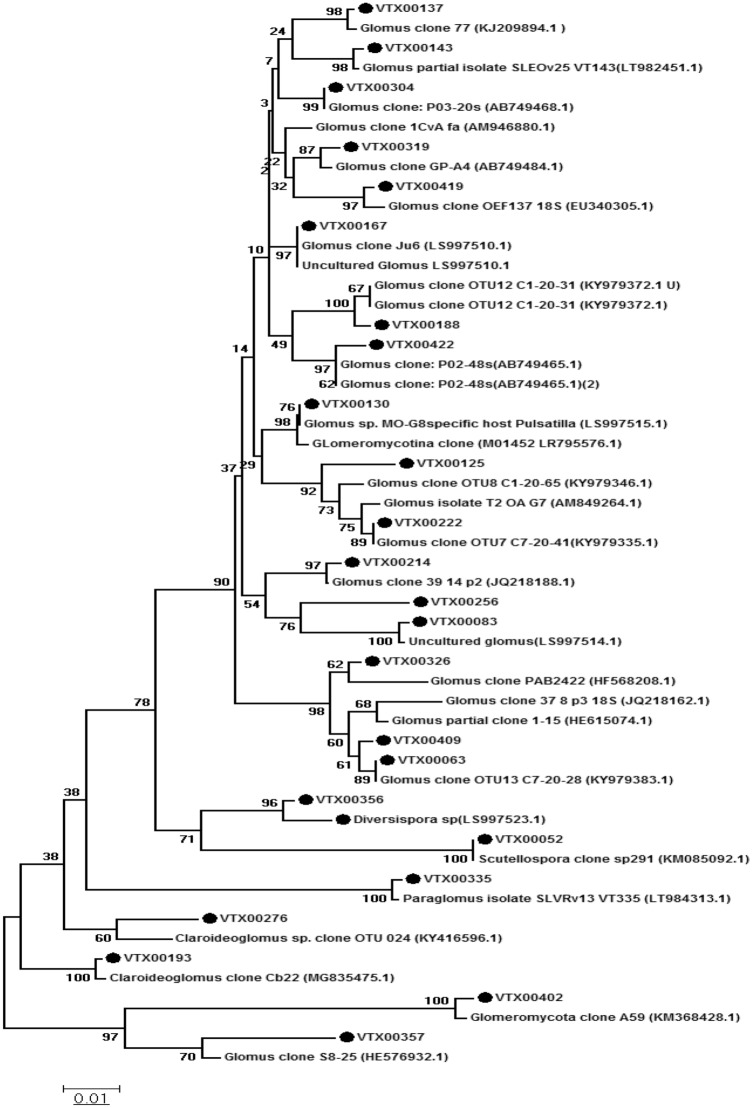

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the maximum likelihood method of SSU rRNA sequences from different AMF species isolated from the rhizosphere of L. cicera grown in the Al Aitha region in northern Tunisia. Bootstrap values ≥ 50 are indicated for each node (1000 replicates). The scale bar indicates 0.05 substitutions per site. The identity of virtual taxa (VTX) isolated in this study can be inferred from the next closest neighbor in the phylogenetic tree

Preparation of the AMF consortium and its characterization by Illumina Miseq

AMF culture

AMF spores were collected from L. cicera rhizosphere in the Al Aitha area located in the northern parts of Tunisia (36° 41′ N, 10° 35′ E) known as a semi-arid zone. The soil had a pH = 7.7 and a conductivity of 0.09mS/m. For isolation of AMF spores, 150 g of soil was mixed with 1.5L of water in 2L conical flasks. The soil mixture was agitated vigorously for 40 min to release the AMF spores from the soil, and then the supernatant was passed through 2 types of sieves (100 µm and 50 µm). Spores were picked by pipette using binocular magnifier (20–40X) (Figure S3) (Gerdemann and Nicolson 1963). Spores were cultured in corn grown in sterilized peat and perlite mixture (substrate). Seedlings of corn were transferred to pots (10 × 10× 12 cm) containing 1 l of the sterilized substrate after germination on moist filter paper in Petri plates and incubated at 25 °C for 5 days in the dark. Thereafter, spores were placed in direct contact with the root system. Plants were placed in a greenhouse under controlled conditions (see above) and irrigated once or twice a week with sterile distilled water (SDW). The multiplication of spores took four months and the inocula were tested before use for the presence of AMF (Figure S4) in the infected roots as previously described by Phillips and Hayman (1970).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Samples of 0.5 g of rhizospheric soil from Al Aitha were used for DNA extraction using FastDNA™ Spin Kit for Soil. The extracted DNA from rhizospheric soil was eluted using 20 μl of DNase/Pyrogen-Free Water (DES). Then, DNA was diluted (1:5) with DES for amplification of partial nuclear ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene fragments by PCR using primers designed to amplify SSU rRNA genes from all AM fungi Wanda (5′-CAGCCGCGGTAATTCCAGCT-3′) (Dumbrell et al. 2010) and AML2 (5′-GAACCCAAACACTTTGGTTTCC-3′) (Lee et al. 2008). In a final volume of 20 μl, a first PCR reaction (PCR-1) was performed with 1 µl (20–50 ng) of extracted DNA, 0.4 μl of each primer (0.4 μM), 0.2 μl Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (0.02Uμl−1) (ThermoFisher Scientific), 1.6 μl of dNTPs (200 μM), and 4 μl of 5X Phusion buffer, 0.5 μl of BSA (20 mg/ml). The PCR-1 reaction was realized with the following program: 99 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 99 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 20 s, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR reactions included also negative controls (sterile water). The amplification products were checked by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels. PCR products were purified using the MicroElute™ DNA Clean-Up Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA, USA) and quantified using a NanoDrop™ Spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Amplicons obtained during the PCR-1 reaction were diluted 1:10 and used as template for a second PCR reaction (PCR-2), using the same primers as in PCR-1, but extended for 8 bp Illumina barcodes, and Illumina adapters (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The PCR-2 reaction was performed according to the following protocol: 99 °C for 5 min followed by 20 cycles of 99 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 20 s, and a final elongation for 10 min at 72 °C. Sequencing was carried out by Magigene (Cuangzhou, Guangdong, China) on an Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform.

Sequence data analysis

The DADA2 plugin was applied for the filtration of paired-end sequences (Callahan et al. 2016). Raw reads were demultiplexed by allowing one mismatch within the barcode. Sequences were trimmed in order to keep only bases with quality scores > 35. Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASV) clustering at 97% identity was performed with the QIIME Software (Caporaso et al. 2010). The presence of chimeras in combined reads was checked by USEARCH (v7.0.1090, Edgar et al. 2010) using database mode at default parameters and MaarjAM database. Virtual taxa (VT) are represented by a type sequence in the MaarjAM database (Öpik et al. 2010a, b, 2014) and determined based on phylogenetic clustering and similarity analyses. BLAST cluster (legacy BLAST v2.2.26, Altschul et al. 1990) was then used for sequences clustering with 97% sequence identity. Criteria for a BLAST match were: sequence similarity ≥ 97%; an alignment length ≥ 95% of the shorter of the query Illumina read and reference database sequence; and a BLAST e-value < 1e−50 (Davison et al. 2011). The 25 VT were identified based on the closest NCBI accession number (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analyses of the AMF species isolated from the rhizosphere of L. cicera in the Al Aitha region were performed using the Maximum Likelihood method with a bootstrapping of 1000 with the MEGA6 software (Tamura et al. 2013).

Isolation of bacterial strains, biochemical analysis, DNA sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis

The PGPB strains LC3.5, LC2.3 and LC5.2 were isolated from roots of L. cicera. The isolation of PGPB was carried out as follows: the root surface was sterilized by immersion in 70% alcohol for 2 min and then in 3% of sodium hypochlorite (10 min), followed by five washes with sterilized water. Root samples were cut into small pieces and plated in triplicate onto Petri dishes containing LB. Then, the plates were incubated at 28ºC for two days. Pure bacterial cultures were obtained by isolating and amplifying single colonies on LB. To ensure root surface disinfection, 200 µl of water from the last wash was plated on LB medium and incubated for 3 days at 28 °C. The solubilization of phosphate was carried out according to Pikovskaya (1948) on a medium containing Ca3(PO4)2 as a source of phosphate. A volume of 2 μl of each bacterial culture was deposited on the surface of the PVK medium before incubation at 30 °C for 24 h. A transparent region around bacterial colonies indicated the solubilization of phosphate. The diameter of the transparent halo was then determined to estimate solubilization activity (Figure S5). The production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) was estimated according to Dworkin and Foster (1958) based on Dworkin and Foster medium (DF) to which tryptophan (1 g/l) was added for the production of IAA (Penrose and Glick, 2003). Bacterial cultures (100 µl) were incubated in this medium at 30 °C for 3 days. The cultures were then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant (1 ml) was mixed with 2 ml of Salkowski's reagent (50 ml of 35% perchlorhydric acid, 1 ml of 0.5 M FeCl3,) and 100 µl ortho-phosphoric acid (10 mM). The absorbance was measured at 530 nm and IAA concentrations were determined using a standard curve. The production of siderophores around bacterial colonies was assessed according to Schwyn and Neilands (1987). Briefly, bacteria were cultured on Chrome Azurol S (CAS) solid medium. An orange halo indicated siderophore production, which was quantified by measuring its diameter (Figure S6). To determine salt tolerance, bacteria were cultured on LB medium containing different concentrations of NaCl (0 µM, 600 µM, 800 µM, 1 M and 1.5 M). Precultures of four replicates for each bacterial strain were cultured in LB medium for 24 h and then 2 μl of each bacterial pre-culture was used to inoculate LB medium containing the different NaCl concentrations. 3 days later, bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 620 nm. Molecular identification of PGPR strains was carried out at the National Research Council, Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection, 10,125 Torino (TO), Italy. The small subunit (SSU) bacterial ribosomal RNA gene (16S) was amplified with bacterial universal primers 27F‐1492R (Lane 1991). The PCR reactions were carried out in a final volume of 25 µl containing 10 µl of Platinum Hot Start PCR Master Mix (2X), 0.5 µl of each primer (10 µM), template DNA (1 µl) and 13 µl of PCR grade water. The PCR cycling was performed with the following program: 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation (60 s at 94 °C), annealing (60 s at 58 °C) and extension (60 s at 72 °C) and a further 7 min final extension at 72 °C. All the PCR products were checked using 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Replicate PCR reactions for each strain were pooled and purified using Wizard SV Gel and a PCR Clean-Up System kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Purified PCR products were sequenced, using either the universal primer 27F or 1492R, by LMU sequencing services (Munich, Germany). MEGA6 software was used for the phylogenetic analyses (Tamura et al. 2013) using the Maximum Likelihood method with a bootstrapping of 1000. Finally, the bacterial sequences were deposited at NCBI (accession # MN879506: LC3.5; accession # MN879507: LC5.2; accession # OM223866: LC2.3).

Biochemical parameters

Determination of sugar content

Total sugars were extracted from shoot tissues by heating shoots with ethanol: water mixture (70: 30 v/v) (Cross et al. 2006). Extracted sugars were converted to furfural with concentrated H2SO4, then condensed with anthrone to form a green color complex, which was quantified colorimetrically at 620 nm (Hedge and Hofreiter 1962). In the assay, 1 ml of anthrone reagent, 0.5 ml of ethanol 80% and 50 µl of plant extract were combined and incubated for 10 min at 100 °C. The reaction was stopped by incubation in an ice bath. Measurements were taken in triplicate using a Biochrom Libra S22 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer. Total carbohydrate content was determined using a standard curve based on glucose and values were presented as mg/ml of glucose equivalents. Three biological replicates were performed and each replicate consisted of three individual plants.

Proline contents

Frozen shoot samples were ground in liquid nitrogen and 50 mg of fresh weight of shoot powder was mixed with 80% ethanol, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min and proline concentration was determined colorimetrically based on proline reaction with ninhydrin as previously reported by Bates et al (1973). In brief, 1 ml of the supernatant was solubilized with 2 ml each of glacial acetic acid and ninhydrin. The mixture was then incubated at 100 ºC for 1 h. The chromophore was extracted with 4 ml toluene and its absorbance was determined using a Biochrom Libra S22 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer at 520 nm. A calibration standard curve of proline was then used for the quantification of proline content.

Antioxidant enzyme assays

For all antioxidant enzyme assays, three biological replicates were performed and each replicate consisted of three individual plants. Frozen shoots were powdered using a mortar in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Then, 500 mg of the powder was used to extract soluble proteins re-suspending them in 2 ml extraction buffer (1 mM PMSF, potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM; pH = 7.8), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT). Control samples (without plant extract) were run for each antioxidant enzyme activity.

Ascorbate peroxidase

The ascorbate peroxidase activity was assessed according to Nakano and Asada (1981) by measurements of the decrease in absorbance of the oxidized ascorbate at 290 nm for 5 min. The reaction mixture contained 50 μl plant extract, 25 μl H2O2 (200 mM), 925 μl of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7) and 0.25 mM ascorbate. The ascorbate peroxidase activity was determined using the extinction coefficient for ascorbate (2.8 mM−1 cm−1), and enzyme activity values were calculated as μmol min−1 mg−1 protein of oxidized ascorbate.

Superoxide dismutase

The method of Yu and Rengel (1999) was used for determining superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. This method relies on the capacity of SOD to reduce NBT (nitroblue tetrazolium) photochemically. The reaction mixture is composed of 190 µl of 50 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (pH = 7.6), 13 mM methionine, 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH = 10.4), 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 µl riboflavin (200 μM), 2 µl NBT (7.5 mM), Triton X-100 (0.025% w/v), and 6 μl of plant extract. The reaction was performed in Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader (Bio Tek A part of Agilent, Switzerland). The addition of riboflavin initiated the chemical reaction, and after 10 min of incubation under continuous fluorescent light, the A560 was monitored. One unit of SOD represents the amount of enzyme necessary for inhibiting the reduction of NBT by 50% (Beauchamp and Fridovich 1971).

Catalase

Catalase activity was assessed by monitoring the decrease in A240 nm corresponding to H2O2 decomposition for 3 min (Aebi 1984). The reaction mixture was composed of 30 μl of plant extract in 950 μl phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH = 7) and 20 μl of H2O2 (500 mM). Catalase activity was determined based on the extinction coefficient of H2O2 (36 M−1 cm−1) and values are presented as μmol min−1 mg−1 protein.

Gene expression analysis

Identification and characterization of HKT1 and NHX7 putative genes in L. cicera and L. sativus transcriptomes

The NHX7 protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana (AtNHX7, AtSOS1) and Cicer arietinum (CaSOS1) were used as queries for searching their homologs in Lathyrus cicera (LcNHK7) and L. sativus transcriptomes using the tblastn function at NCBI (Santos et al. 2018). The HKT1 protein sequence of Medicago trancatula (MtHKT1) was used as a query to find Lathyrus cicera HKT1 (LcHKT1) protein sequence using the tblastn function at NCBI. The identity of the homologs in L. cicera was further confirmed by searching their corresponding conserved domains which are TrKH and Na-H-Exchanger for HKT and NHX families, respectively, using SMART program (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/).

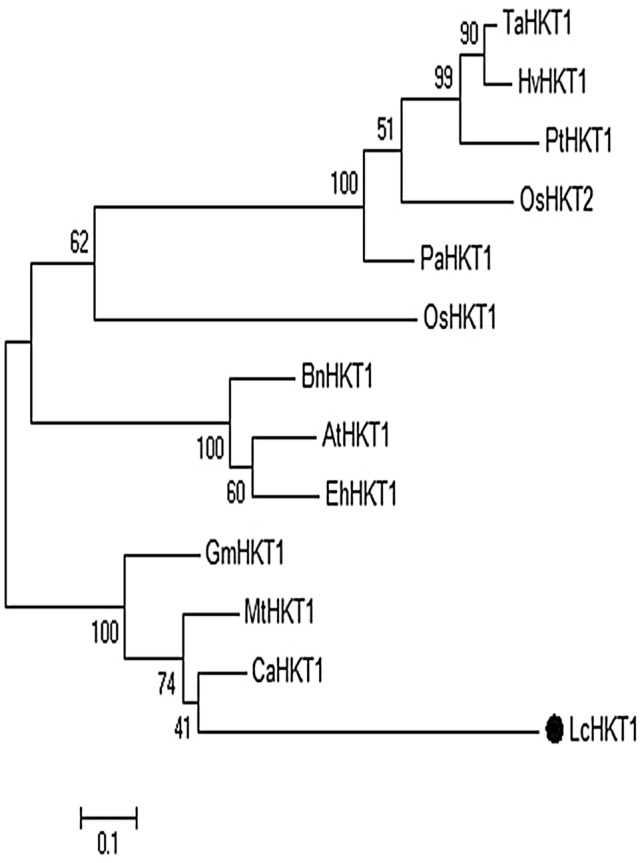

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

LcNHK7 and LcHKT1 protein sequences and their homologous in other plant species were aligned by Clustalw and conserved regions were shaded using GenDoc software. MEGA6 software was then used for constructing the phylogenetic tree based on the neighbor-joining method with a bootstrapping of 1000.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from L. cicera roots using Spectrum™ Plant Total RNA Kit (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified by CytationCell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader machine (BioTek, Switzerland). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA using SensiFAST™ cDNA Synthesis KIT (BiolineReagents Ltd) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using a Mic qPCR Cycler (Bio molecular Systems) with the following cycle conditions: 15 min at 95 °C followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C and 30 s at72 °C. The γ-tubulin gene was used as a reference gene according to (Santos et al. 2018). Genes and their corresponding primers are shown in Table S2. The reaction was performed using the Fast Start Universal SYBER Green Master (ROX) (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Germany) in a volume of 15 μl in a buffer containing the SYBER qPCR Master mix, 10 µM primers and tenfold diluted reverse-transcribed RNA. The 2−∆∆Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) was applied for relative quantification of gene expression levels. The relative amount of each gene transcript was normalized to the amount of transcripts of the internal control in the same cDNA. Five technical replicates were performed for each treatment and the whole biological experiment was conducted twice independently.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 21 software was used for the statistical analysis of the results based on ANOVA method. Significance of the differences between mean values was determined with Tukey’s HSD test (P ≤ 0.05).

Results

Identification of AMF species from the rhizosphere of L. cicera et al. Aitha using Illumina Miseq

AMF species were isolated from the rhizosphere of L. cicera in the “Al Aitha” region in northern Tunisia, and their phylogenetic identity was assessed based on ribosomal RNA sequences (SSU rRNA) (Fig. 1). Using the MaarjAM database (Öpik et al. 2010a, b), 25 Virtual taxa (VT) were annotated from five families (Claroideoglomeraceae, Diversisporaceae, Glomeraceae, Paraglomeraceae and Gigasporaceae) encompassing five genera (Glomus, Claroideoglomus, Diversipora, Paraglomus and Scutellospora). The identity of the different VTs, relative to previously identified AMF isolates was determined by phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). Glomus was found to be the dominant genus, followed by Claroideoglomus one, while, the remaining genera were less abundant in the rhizosphere of L. cicera. This indicates that Glomus may be the most adapted AMF genus in this semi-arid region.

Characterization of PGPB strains

Three endophytic bacterial strains (LC2.3, LC 5.2, and LC3.5) were isolated from the roots of L. cicera and tested for their PGPB characteristics. Initial growth tests showed that the bacterial strains can grow under high NaCl concentrations (up to 1 M) (Table S3). They produced high amounts of IAA (Table S4), and they were found to be very effective in phosphate solubilization and siderophore production (Table S4). Phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed their taxonomic position relative to previously identified PGPB (Figure S7). The strains LC2.3, LC 5.2 and LC3.5 were found to be closely related to B. simplex, B. megaterium and B. subtilis, respectively, with an identity ranging from 98 to 100%.

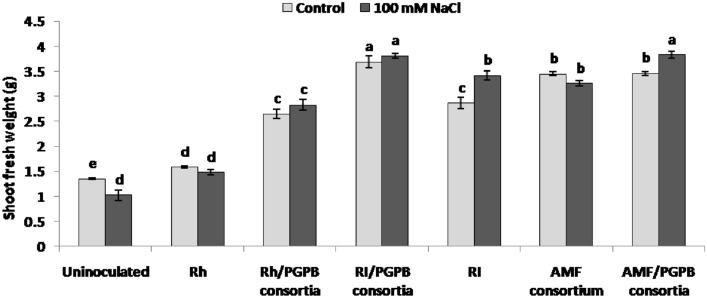

Effect of inoculation treatments on plant growth

To evaluate the effects of the various microbial inocula on alleviating salt stress, shoot fresh weight (all aerial parts of the plant) was measured (Fig. 2). Salt stress induced a reduction in shoot biomass by 24% in uninoculated stressed plants compared to uninoculated and non-stressed. In contrast, inoculated plants generally showed a higher shoot weight than uninoculated and non-stressed ones. Plants inoculated with AMF/PGPB consortia and RI/PGPB consortia showed the highest increase in shoot biomass, followed by plants inoculated with RI, the AMF consortium, and combined Rh/PGPB consortia compared with uninoculated stressed plants (Fig. 2). Only a slight increase in shoot biomass was detected in plants inoculated with rhizobium alone (Rh) compared with uninoculated stressed plants (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of different inocula on shoot biomass of L. cicera (30 days-old plants) under control conditions (light grey) and salt stress conditions (100 mM NaCl; dark grey). Columns represent the average of three biological replicates ± standard error. Values with a shared letter are not significantly different according to the HSD Tukey test (p < 0.05)

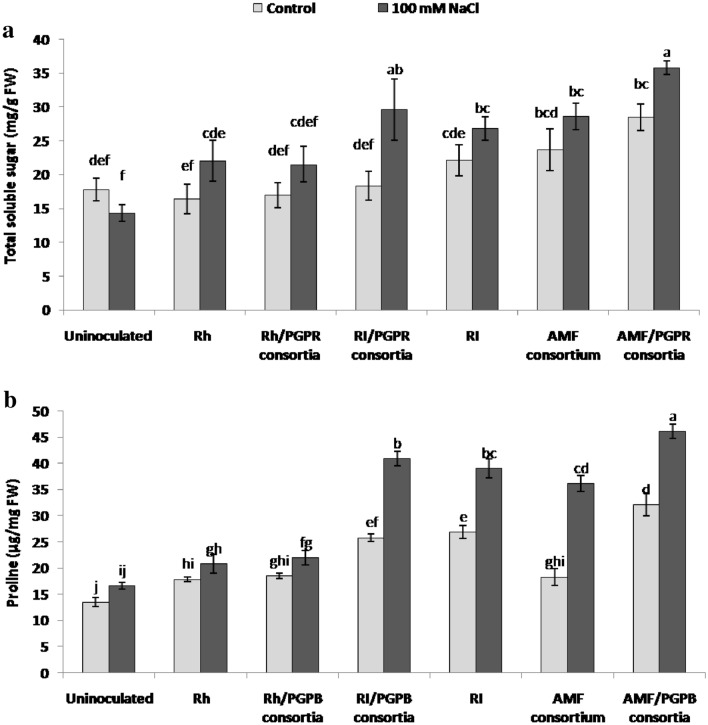

Effect of inoculation treatments on osmotic adjustment and antioxidant pathways

Plants can alleviate high salt stress by adjusting the osmotic status of the cells through the accumulation of osmolytes such as sugars and proline (Anjum et al. 2017). Determination of total soluble sugars revealed that for inoculated plants, their levels tended to be generally higher in salt-stressed plants, relative to the respective uninoculated and non-stressed plants, whereas non-inoculated plants exhibited the lowest levels of sugars, irrespective of salt stress (Fig. 3a). Statistical analysis revealed that only in the case of RI/PGPB and AMF/PGPB, the increase in sugar content of inoculated plants was significant. Salt-dependent increases in proline levels were even larger than for sugars, in particular in treatments that involved a mycorrhizal inoculum (RI/PGPB, RI, AMF and AMF/PGPB) (Fig. 3b). Plants inoculated with Rh or Rh/PGPB exhibited slightly higher levels than non-inoculated plants, however, salt stress did not cause a further increase in proline content (Fig. 3b). Besides osmotic stress, high salt causes the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in a cellular imbalance of redox homeostasis (Bhatti et al. 2013) Several plant antioxidant systems play an important role in ROS scavenging to avoid cellular damage (Ajithkumar 2014; Yang et al. 2015). In our present study, the activities of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) were measured to determine whether they could be involved in the mitigation of salt-induced oxidative stress by the different inoculation treatments. Salt stress caused an increase in CAT activity, in particular in inoculated plants, except for the Rh and Rh/PGPB treatments (Fig. 4a). SOD activity was induced in all stress treatments, with slightly higher levels in inoculated plants compared to non-inoculated and non-stressed plants (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, APX activity was decreased by salt stress in uninoculated plants, while inoculated ones exhibited a general increase upon salt stress (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 3.

Effect of different inocula on the accumulation of total soluble sugar (a) and proline (b) content in shoots of L. cicera (30 days-old plants) under control conditions (light grey) and salt stress conditions (100 mM NaCl; dark grey). Columns represent the average of three biological replicates ± standard error. Values with a shared letter are not significantly different according to the HSD Tukey test (p < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Effect of different inocula on catalase activity (a), superoxide dismutase activity (b) and ascorbate peroxidase activity (c) in shoots of L. cicera (30 days-old plants) under control conditions (light grey) and salt stress conditions (100 mM NaCl; dark grey). Columns represent the average of three biological replicates ± standard error. Values with a shared letter are not significantly different according to the HSD Tukey test (p < 0.05)

Establishment of LcHKT1 and LcNHX7 as salinity tolerance marker genes for L. cicera

The expression of certain genes can be related to salt stress tolerance and they can be considered as salt stress markers (Sharma and Ramawat 2014; Deinlein et al. 2014). For example, high-affinity potassium transporter1 (HKT1) and Na+/H+ exchanger7/Sodium Overly Sensitive1 (NHX7/SOS1) gene expression is correlated with salt stress, and they directly promote salt tolerance (Zhu 2003; Yamaguchi et al. 2013; Garcia de la Garma et al. 2015). We first identified the closest homologues of HKT1 and NHX7 from the L. cicera transcriptome (Santos et al. 2018), and performed a phylogenetic analysis at the amino acid sequence level in order to test whether they represent bona fide orthologues of the functionally characterized genes in other species. The alignment of LcHKT1 and twelve HKT proteins from other organisms revealed the presence of six conserved domains (five transmembrane regions and the TrkH domain) (Figure S8), and showed that LcHKT1 is closely related to CaHKT1 and MtHKT1 from other legumes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree based on an alignment of the LcHKT1 protein sequence with 12 other HKT-type proteins. The tree was constructed using MEGA6 with maximum likelihood and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers indicate percentage bootstrap support. The scale bar indicates 0.1 substitutions per site. Protein accession numbers are the following AtHKT1: AAF68393; TaHKT1: AAA52749; HvHKT1: CAJ01326; PaHKT1: BAE44385; OsHKT1: BAB61789; OsHKT2: BAB61791; PtHKT1: ACT21087. BnHKT1: XP_013732854.1; GmHKT1: XP_014620373.3; MtHKT1: XP_013732854.1; CaHKT1: XP_004513109.1; EhHKT1: ABK30935.1

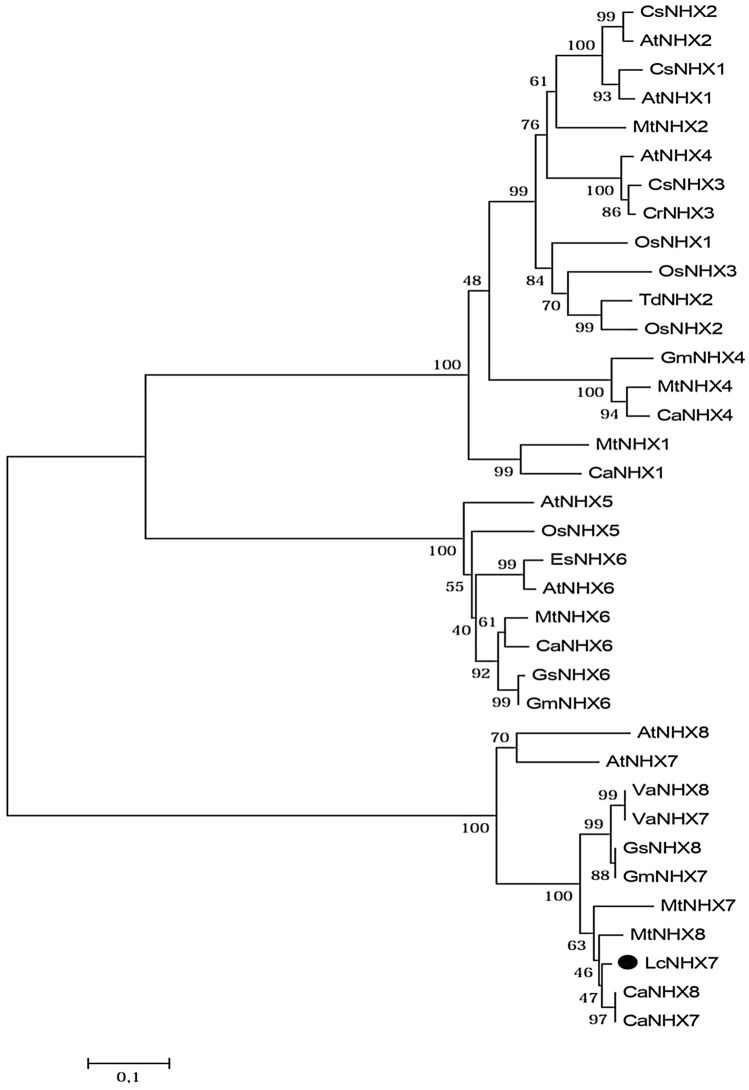

The sequence alignment of LcNHX7 and its homologues from other organisms revealed the presence of the Na-H-Exchanger conserved domain starting from position 1 to 358 (Figure S9). The phylogenetic tree of LcNHX7 and other NHX proteins from various organisms is presented in Fig. 6. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the NHX gene family contains eight members that can be divided into three groups based on their sequence similarity and subcellular localization (Fig. 6). AtNHX7 and AtNHX8 belong to the PM-class (localized to the plasma membrane), AtNHX5 and AtNHX6 belong to the Endo-class (localized to endosomes), and four genes (AtNHX1-4) belong to the Vac-class (localized to the vacuolar membrane) (Shi et al. 2000; Brett 2005; Bassil et al. 2011). As previously described, our phylogenetic analysis shows that the NHK protein family is divided into three major clades. LcNHX7 clusters together with CaNHX7, CaNHX8, MtNHX7 and MtNHX8, and with AtNHX7 and AtNHX8 of the PM class. Since these sequences cluster separately from all other NHX sequences, they may represent an orthologous group with a common evolutionary origin.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree based on an alignment of the LcNHX7 protein sequence with other NHX-type proteins. The tree was constructed using MEGA6 with maximum likelihood and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers indicate percentage bootstrap support. The scale bar indicates 0.1 substitutions per site. Protein accession numbers are as following OsNHX1: ATU90108.1; OsNHX2: ATU90109.1; OsNHX3: ATU90110.1; OsNHX5: ATU90112; TdNHX2: XP_037429867.1; AtNHX1: AED93655.1; CsNHX1: XP_013663082.1; AtNHX2: OAP06770.1; AtNHX4: OAP02002.1; AtNHX3: OAO94427.1; AtNHX5: NP_175839.2; AtNHX6: OAP16827.1; AtNHX7: AEC05529.1; AtNHX8: NP_001184995.1; Mt NHX1: AES61316.2; Mt NHX2: Mt NHX6: XP_013469021.1; Mt NHX4: XP_003600216.2; Mt NHX8: XP_039684715.1; CaNHX1: XP_027189311.1; CaNHX6: XP_004486408.1; CaNHX7: XP_027191972.1; CaNHX8: XP_004504612.1; GmNHX7: RZB96017.1; GmNHX6: XP_006597645; GsNHX8: XP_028243295.1; GsNHX6: RZB90181.1; VaNHX7: XP_017406433.1; VaNHX8: XP_017406431.1

Effect of inoculation on the expression of salt stress markers LcHKT1 and LcNHX7

The high-affinity potassium transporter1 (HKT1) and the Na+/H+ exchanger7/Sodium Overly Sensitive1 (NHX7/SOS1) are functionally well-defined salt-stress-related genes, that directly promote salt tolerance in plants (Zhu et al. 2003; Garcia de la Garma et al. 2015). Therefore, we identified their homologues in L. cicera and used them as genetic markers for salt stress tolerance. Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) revealed that HKT1 is induced by salt stress, but only in plants inoculated with AMF, or with the combinations AMF/PGPB or PGPB/RI (Fig. 7a). Similarly, NHX7 showed a general tendency to be induced in stressed plants, but only in the case of AMF/PGPB and RI/PGPB the difference was significant (Fig. 7b). Taken together, both genes were not induced by salt stress alone, but only in the combination of microbial inoculation and salt stress. An interesting exception is the inoculation with AMF/PGPB, which induced both genes by its own, suggesting that it primed the plants for salt stress, even before exposure to the stress.

Fig. 7.

Relative expression levels of HKT1 (a) and NHX7 (b) in roots of L. cicera under control (light grey) and saline conditions (100 mM NaCl; dark grey). Columns represent the average of five biological replicates ± standard error. Values with a shared letter are not significantly different according to the HSD Turkey test (p < 0.05)

Discussion

Soil salinity adversely affects the growth and yield of many crops (Mantri et al. 2012). The detrimental effects of salinity lead to morphological, biochemical and molecular changes (Aftab et al. 2011). The use of beneficial microorganisms was reported to increase crop yield under salt stress conditions, in particular certain PGPB, such as the genera Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Enterobacter, Agrobacterium, Streptomyces, Klebsiella, and Achromobacter (Niu et al. 2018). The application of PGPB enhanced plant growth and productivity particularly in the arid and semi-arid regions (Sharma et al. 2016; Singh and Jha 2016; Sarkar et al. 2018). Also, pretreatments with AMF have been reported to promote plant growth by increasing the mineral nutrient supply (Bowles et al. 2016). In our present work, the AMF consortium obtained from the soil in “Al-Aitha” region contains five genera including Glomus, Claroideoglomus, Diversipora, Paraglomus, and Scutellospora. This is in accordance with the findings reported by Tsiknia et al. (2021), who used primers that target only the SSU region 18S of the rRNA genes. They found that in Mediterranean sand dune habitats, Glomus was the dominant genus, followed by the genera Scutellospora, Acaulospora, Diversispora, and Paraglomus) (Tsiknia et al. 2021). The generally high colonization levels by the Glomus group may reflect its good adaptability to Mediterranean semi-arid conditions (Mosbeh et al. 2018; Tsiknia et al. 2021). The genus Glomus is known for its high spore production and short generation time (Koch et al. 2017), which may contribute to its dominance. However, environmental factors are also known to influence AMF diversity. For example, alkaline soils can foster the dominance of Glomus species (Oehl et al. 2010).

Our results showed that salinity (100 mM NaCl) significantly reduced L. cicera plant growth, an effect that was alleviated by inoculation with RI/PGPB and AMF/PGPB (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with those of Motaleb et al (2020) who showed that the co-inoculation of Phaseolus vulgaris with R. irregularis and Bacillus megaterium improved shoot biomass under salt stress. In response to salt stress, plants accumulate compatible osmolytes such as sugars and proline in the cytosol, which can adjust osmotic balance and ultimately replace water, thereby protecting cell structure and helping in maintaining protein functioning (Latef and Miransari 2014). We found here that high amounts of osmolytes related to osmotic adjustment were accumulated in L. cicera inoculated either with RI/PGPB or AMF/PGPB (Fig. 3a, b). This corroborates the results of Hashem et al (2016) who showed that the combination of AMF and PGPR increased total soluble sugar and proline contents in Acacia gerrardii under saline conditions. The synergistic effect of PGPB and AMF in alleviating salt stress was previously deciphered in some plant species (Hidri et al. 2016; Bharti et al. 2016). A possible mechanism is the release of stimulatory compounds by PGPB that promote host colonization by AMF (Jeffries et al. 2003). AMF in turn helps the plant to resist abiotic stresses by increasing the total absorptive surface area of the root system for nutrient and water uptake (Ruiz-Lozano et al. 2012).

Salt stress increases ROS levels leading to oxidative damage of membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids (Saleem et al. 2020). Inducible antioxidant enzymes can detoxify ROS, in particular catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), as well as the enzymes of the ascorbate (ASC)–glutathione (GSH) cycle comprising GSH reductase (GR), ASC peroxidase (APX), and monodehydroascorbate dehydrogenase (MDHAR), and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) (Gill and Tuteja 2010, Gill et al. 2013). SOD converts O2− to H2O2, which in turn is neutralized by the activity of CAT in the cytosol. APX is the key enzyme in H2O2 detoxification in chloroplasts and it also plays a role in ROS scavenging in the cytosol, mitochondria, and peroxisomes. This enzyme uses ascorbic acid as an electron donor to reduce H2O2 to water (Shigeoka et al. 2002). The increase of antioxidant enzyme activity in plants promotes ROS scavenging, thereby protecting cell constituents from lipid peroxidation (Mittler 2002).

All microbial inoculations significantly increased antioxidant enzymes, except for of CAT in rhizobial treatments (Fig. 4a). Also, there is a clear tendency for synergism in CAT and APX (Fig. 4a, c). Our results are consistent with several studies that showed that mycorrhizal symbiosis protected plants against salt stress by enhancing the activities of antioxidant enzymes (Alguacil et al. 2003; Zhong et al. 2007; Evelin et al. 2013). Furthermore, our results corroborate those of Motaleb et al (2020) who showed that the synergistic interaction between AMF and PGPR promoted the antioxidant enzyme system in bean plants. On the same trends, the combined application of mycorrhizal fungi and PGPR was reported to increase antioxidant enzyme activity in common bean plants under saline conditions (Younesi and Moradi, 2014). In this present work, SOD activity was increased by all microbial treatments (Fig. 4b), indicating that microbial inoculation boosted SOD activity as the first line of defense to overcome the ROS burden (Singh et al. 2010).

Plant exposure to high levels of NaCl results in ion toxicity due to Cl− and Na+ accumulation causing damage to cellular structures and metabolism. Na+/K+ homeostasis can be restored either by Na+ removal (cellular efflux) or sequestration (e.g. compartmentalization to the vacuole). Sequestration is performed by Na+/H+ exchanger (NHX) proteins that are located at the tonoplast, while, Na+ efflux is mediated by NHX7/SOS1, which is localized to the plasma membrane of root epidermal cells of plants (Zhang et al. 2001; Zhu, 2003). Furthermore, Na+ removal from xylem to xylem parenchyma cells is carried out by HKT1, located mainly in the xylem/symplast boundary of roots and shoots (Sunarpi et al. 2005). In response to salt stress, previous work showed a reduction in Na+ accumulation in the cytosol and a reduced root-to-shoot allocation of Na+ (Evelin et al. 2012; Porcel et al. 2016).

In our present study, the behavior of two salt tolerance marker genes involved in Na+ uptake and translocation was investigated. We found that the expression level of HKT1 was strongly upregulated in plants inoculated with AMF, alone or in combination (AMF/PGPB, RI /PGPB, and AMF) (Fig. 7a). This is consistent with the findings of Chen et al. (2017) who described that AMF inoculation upregulated the expression of HKT1 in roots of Robinia pseudoacacia. Thus, the induction of HKT1 in roots of L. cicera under the different inocula suggests that Na+ is unloaded from the xylem in order to restrict its allocation to the shoots (Deinlein et al. 2014).

In addition, we observed an upregulation of NHX7 in roots of L. cicera after the treatment with different inocula (Fig. 7b), particularly, AMF/ PGPB. This is in accordance with the findings previously reported by Selvakumar et al (2018), who described an important upregulation of the ZmSOS1 gene in plants co-inoculated with C. lamellosum and P. koreensis S2CB35 in Zea mays. Thus, the upregulation of NHX7 in roots of L. cicera under the different inocula suggests that Na+ can be exported back to the soil or the apoplast since the toxicity of sodium is reduced in the apoplastic space (Shi et al. 2002). Collectively, our findings show that salinity tolerance in L. cicera was significantly enhanced by inoculation with AMF and PGPB, either separately, or even more when applied in combination (AMF/PGPB).

Concluding remarks

Our current study revealed that salt stress negatively affects L. cicera plant growth and a number of biochemical facets. However, the inoculation of this legume with different inocula significantly alleviated salt stress, reflected by promoted plant growth, increased osmolyte content, and induction of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, SOD, APX, and increased expression of the salt tolerance markers HKT1 and NHX7. Importantly, a strong synergism was found between the AMF consortium and the combined PGPB, since the AMF/PGPB treatment performed better than any other single or combined treatment. This synergism was observed in virtually all assessed traits, suggesting that the synergism between diverse AMF and PGPB consortia is a powerful tool to overcome salt stress. We propose that AMF/PGPB combination should be tested under field conditions for enhancing salt tolerance in L. cicera and related legumes, particularly in semi-arid and arid regions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Maria Carlota VazPatto and Dr Carmen Santos for providing HKT1 and NHX7 gene sequences from their unpublished L. cicera transcriptomic databases. This research was funded by scholarships from the "International Relations Office Frau Veronika Favre", University of Fribourg and the Tuniso-Moroccan bilateral project (20/PRD03).

Declarations

Conficts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conficts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/2/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12298-023-01317-5

References

- Abdel Latef AA, Miransari M (2014) The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in alleviation of salt stress. Use of microbes for the alleviation of soil stresses in Springer Science+Business Media. New York USA: 23–39

- Aebi H. Catalase Methods in Enzymology. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aftab T, Khan MMA, Silva JAT, Idrees M, Naeem M. Role of salicylic acid in promoting salt stress tolerance and enhanced artemisi nin production in Artemisia annua L. J Plant Growth Regul. 2011;30:425–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ajithkumar IPPR. ROS scavenging system osmotic maintenance pigment and growth status of panicum sumatrense roth. Under Drought Stress Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;68:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alguacil MM, Hernández JA, Caravaca F, Portillo B, Roldán A. Antioxidant enzyme activities in shoots from three mycorrhizal shrub species afforested in a degraded semi-arid soil. Physiol Plant. 2003;118:562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman D. Basic local alignment searchtool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum SA, Ashraf U, Tanveer M, Khan Hussain S, Shahzad B, Zohaib A, Abbas F, Saleem MF, Ali I, et al. Drought induced changes in growth osmolyte accumulation and antioxidant metabolism of three maize hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:69. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassil E, Tajima H, Liang YC, Onto MA, Ushijima K, Nakano R, Esumi T, Coku A, Belmonte MBE. The Arabidopsis Na+/H+ antiporters NHX1 and NHX2 control vacuolar pH and K+ homeostasis to regulate growth flower development and reproduction. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3482–3497. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare I. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti N, Barnawal D, Shukla S, Tewari SK, Katiyar RS, Kalra A. TA. integrated application of Exiguobacterium oxidotolerans Glomus fasciculatum and vermicompost improves growth yield and quality of Mentha arvensis in salt-stressed soils. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;83:717–728. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti KH, Anwar S, Nawaz K, Hussain K, Siddiqi E, Sharif R, Talat AKA. Effect of exogenous application of glycinebetaine on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under heavy metal stress Middle East. J Sci Res. 2013;14:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco C, Defez R. Medicago truncatula improves salt tolerance when nodulated by an indole-3-acetic acid-overproducing Sinorhizobium meliloti strain. J Exper Botany. 2009;60:3097–3107. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouksila F, Bahri A, Berndtsson R, Persson M, Rozema J, Van der Zee S. Assessment of soil salinization risks under irrigation with brackish water in semiarid Tunisia. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;92:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles TM, Barrios Masias FH, Carlisle EA, Cavagnaro TR, Jackson LE. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizae on tomato yield nutrient uptake water relations and soil carbon dynamics under deficit irrigation in field conditions. Sci Total Environ. 2016;566–567:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes S. High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaca F, Alguacil MM, Hernández JA. Involvement of antioxidant enzyme and nitrate reductase activities during water stress and recovery of mycorrhizal Myrtus communis and Phillyrea angustifolia plants. Plant Sci. 2005;169:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty K, Bose J, Shabala L, Shabala S. Difference in root K+ retention ability and reduced sensitivity of K+ permeable channels to reactive oxygen species confer differential salt tolerance in three Brassica species. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:4611–4625. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhang H, Zhang X, Tang M. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Alleviates salt stress in black Locust through improved Photosynthesis water status and K+/Na+ Homeostasis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1739. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, von Korff M, Altmann T, Bartzetko L, Sulpice R, Gibon Y, Palacios NSM. Variation of enzyme activities and metabolite levels in 24 Arabidopsis accessions growing in carbon-limited conditions. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1574–1588. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison J, Öpik M, Daniell TJ, Moora M, Zobel M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in plant roots are not random assemblages. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;78:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinlein U, Stephan AB, Horie T, Luo W, Xu G, Schroeder JI. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbrell AJ, Nelson M, Helgason T, Dytham C, Fitter AH. Relative roles of niche and neutral processes in structuring a soil microbial community. The ISME J. 2010;4:337–345. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin M, Foster JW. Experiments with some microorganisms which utilize ethane and hydrogen. J Bacteriol. 1958;75:592–603. doi: 10.1128/jb.75.5.592-603.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Akhal MR, Rincón A, Coba Dela Peña T, Lucas MM, El Mourabit N, Barrijal S, Pueyo J. Effects of salt stress and rhizobial inoculation on growth and nitrogen fixation of three peanut cultivars. Plant Biol. 2013;15:415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelin H, Giri B, Kapoor R. Contribution of Glomus intraradices inoculation to nutrient acquisition and mitigation of ionic imbalance in NaCl-stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum. Mycorrhiza. 2012;22:203–217. doi: 10.1007/s00572-011-0392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelin H, Giri B, Kapoor R. Ultrastructural evidence for AMF mediated salt stress mitigation in Trigonella foenum-graecum. Mycorrhiza. 2013;23:71–86. doi: 10.1007/s00572-012-0449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Zhang F, Li X, Tian C, Tang C, Rengel Z. Improved tolerance of maize plants to salt stress by arbuscular mycorrhiza is related to higher accumulation of soluble sugars in roots. Mycorrhiza. 2002;12:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00572-002-0170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreres F, Magalhães SCQ, Gil-Izquierdo A, Valentão P, Cabrita ARJ, Fonseca AJM, Andrade P. HPLC-DADESI/MSn profiling of phenolic compounds from.L. seeds. Food Chem. 2017;214:678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers TJ, Colmar TD. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytologist. 2008;179:945–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de la Garma J, Fernandez-Garcia N, Bardisi E, Pallol B, Rubio-Asensio JS, Bru R, et al. New insights into plant salt acclimation: the roles of vesicle trafficking and reactive oxygen species signalling in mitochondria and the endomembrane system. New Phytol. 2015;205:216–239. doi: 10.1111/nph.12997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants.Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010;48:909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Anjum NA, Hasanuzzaman M, Gill R, Trivedi DK, Ahmad I, et al. Glutathione and glutathione reductase: a boon in disguise for plant abiotic stress defense operations. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;70:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli T, Ellouze W, Chihaoui S A, Barhoumi F, Mhamdi R, Mnasri B (2020) Genotypic and symbiotic diversity of native rhizobia nodulating redpea (Lathyrus cicera L.) in Tunisia. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 43 126049 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hanbury CD, White CL, Mullan BP, Siddique KHM. A review of the potential of Lathyrus sativus L. and L. cicera L. grain for use as animal feed. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2000;87:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem A, Adb Allah EF, Alqarawi AA, Al-Huqail AA, Shah M. Induction of Osmoregulation and modulation of salt stress in Acacia gerrardii Benth by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Bacillus subtilis (BERA 71) Hindawi. 2016;1:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2016/6294098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield JL, Charles LW. Meeting global food needs: realizing the potential via genetics× environment× management interactions. Agron J. 2015;107(4):1215–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Hedge J E ,Hofreiter B T (1962) In: Carbohydrate Chemistry 17. Academic P. Edited by J. N. Whistler R L and Be Miller.

- Hidri R, Barea JM, Mahmoud MB, Abdelly C, Azcón R. No Impact of microbial inoculation on biomass accumulation by Sulla carnosa provenances and in regulating nutrition physiological and antioxidant activities of this species under non-saline and saline conditions. J Plant Physiol. 2016;201:28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad A, Rehman RNU, Abrar MM, Saeed Q, Sharif R, Hu T. Contribution of Rhizobium-Legume symbiosis in salt stress tolerance in Medicago truncatula evaluated through photosynthesis antioxidant enzymes and compatible solutes accumulation. Sustainability. 2021;13:3369. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil A, Riaz S, Ashraf M, Foolad M. Gene expression profiling of plants under salt stress. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2011;30:435–458. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries P, Gianinazzi S, Perotto S, Turnau KBJ. The contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in sustainable maintenance of plant health and soil fertility. Biol Fertil Soils. 2003;37:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Koch AM, Antunes PM, Maherali H, et al. Evolutionary asymmetry in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: conservatism in fungal morphology does not predict host plant growth. New Phytol. 2017;214:1330–1337. doi: 10.1111/nph.14465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Goodfellow M, editor. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics; stackebrandt E. New York, NY, USA: JohnWiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen T. Analysis of relative gene expressiondata using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆Ct method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorent-Martínez EJ, Ortega-Barrales P, Zengin G, Mocan A, Simirgiotis MJ, Ceylan R, Aktumsek A. Evaluation of antioxidant potential, enzyme inhibition activity and phenolic profile of Lathyrus cicera and Lathyrus digitatus: potential sources of bioactive compounds for the food industry. Food and Chem Toxicol. 2017;107:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorent-Martínez E J, Ortega-Barrales P, Zengin G, Mocan A, Simirgiotis M J, Ceylan, Mantri N, Patade V, Penna S, Ford R P E (2012) Abiotic stress responses in plants: present and future. in In: Abiotic stress responses in plants Springer. New York NY : 1–19.

- Mhadhbi H, Djébali N, Chihaoui S, Jebara M, Mhamedi R. Nodule senescence in Medicago truncatula-sinorhizobium symbiosis under abiotic constraints: biochemical and structural processes involved in maintaining nitrogen-fixing capacity. J Plant Growth Regul. 2011;30:480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbah M, Philippe DL, Mohamed M. Molecular identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores associated to the rhizosphere of Retama raetam in Tunisia. Soil Sci Plant Nutrition. 2018;64:335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb NA, Elhady SA, Ghoname A. AMF and Bacillus megaterium neutralize the harmful effects of salt stress on bean plants. Gesunde Pflanz. 2020;72:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts Yoshiyuki. Plant & Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Niu X, Song L, Xiao Y, Ge W. Drought-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria associated with foxtail millet in a semi-arid agroecosystem and their potential in alleviating drought stress. Front Microbiol. 2018;8:2580. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehl F, Laczko E, Bogenrieder A, et al. Soil type and land use intensity determine the composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:724–738. [Google Scholar]

- Öpik M, Vanatoa A, Vanatoa E, Moora M, Davison J, Kalwij JM, Reier Ü, Zobel M. The online database MaarjAM reveals global and ecosystemic distribution patterns in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) New Phytologist. 2010;188:223–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öpik M, Vanatoa A, Vanatoa E, Moora M, Davison J, Kalwij JM, et al. The online database MaarjAM reveals global and ecosystemic distribution patterns in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) New Phytol. 2010;188:223–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öpik M, Davison J, Moora M, Zobel M. DNA-based detection and identification of Glomeromycota: the virtual taxonomy of environmental sequences. Botany. 2014;92:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Patto MC, Skiba B, Pang ECK, Ochatt SJ, Lambein F, Rubiales D. Lathyrus improvement for resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses: from classical breeding to marker assisted selection. Euphytica. 2006;147:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose DM, Glick BR. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase containing plant growthpromoting rhizobacteria. Physiol Plant. 2003;118:10–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JM, Hayman DS. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans Brit Mycol Soc. 1970;55:158–161. [Google Scholar]

- Porcel R, Aroca R, Azcon R, et al. Regulation of cation transporter genes by the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in rice plants subjected to salinity suggests improved salt tolerance due to reduced Na+ root-to-shoot distribution. Mycorrhiza. 2016;26:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s00572-016-0704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu YJ, et al. Mediation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and biochemical parameters of Ligustrum vicaryi in response to salinity. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2020;112:101522. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lozano JM, Porcel R, Azcon R, Aroca R. Regulation by arbuscular mycorrhizae of the integrated physiological response to salinity in plants. New challenges in physiological and molecular studies. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:4033–4044. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem MH, Kamran M, Zhou Y, Parveen A, Rehman M, Ahmar S, Malik Z, Mustafa A, Anjum RMA, Wang B, et al. Appraising growth oxidative stress and copper phytoextraction potential of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) grown in soil differentially spiked with copper. J Environ Manag. 2020;257:109994. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C, Almeida NF, Alves ML, Horres R, Krezdorn N, Trindade Leitão S, Aznar-Fernández T, Rotter B, Winter P, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. First genetic linkage map of Lathyrus cicera based on RNA sequencing-derived markers: Key tool for genetic mapping of disease resistance. Horticulture Res. 2018;5:45. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0047-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Ghosh PK, Pramanik K, Mitra S, Soren T, Pandey S, et al. A halotolerant Enterobacter sp. displaying ACC deaminase activity promotes rice seedling growth under salt stress. Microbiol Res. 2018;169:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar G, Shagol C, Kim K, Han S, Sa T. Spore associated bacteria regulates maize root K+/ Na+ ion homeostasis to promote salinity tolerance during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:109. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Ramawat KG. Salt stress enhanced antioxidant response in callus of three halophytes (Salsola baryosma, Trianthema triquetra, Zygophyllum simplex) of Thar Desert. Biologia. 2014;69:178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kulkarni J, Jha B. Halotolerant rhizobacteria promote growth and enhance salinity tolerance in peanut. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1600. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi HZ, Ishitani M, Kim CZJ. The Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na+/H+ antiporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6896–6901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120170197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Quintero FJ, Pardo JM, Zhu JK. The putative plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 controls long-distance Na+ transport in plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14:465–77. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeoka S, Ishikawa T, Tamoi M, Miyagawa Y, Takeda T, Yabuta Y, et al. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:1305–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Jha P. The Multifarious PGPR Serratia marcescens CDP-13 augments induced systemic resistance and enhanced salinity tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Tiwari N. Microbial amelioration of salinity stress in HD 2967 wheat cultivar by up-regulating antioxidant defense. Commun Integr Biol. 2021;14:136–150. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2021.1937839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh DP, Singh V, Gupta VK, Shukla R, Prabha R, Sarma BK, Patel JS. Microbial inoculation in rice regulates antioxidative reactions and defense related genes to mitigate drought stress. Sci Rep. 2010;10:4818. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61140-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Song J, Xin X, Xie X, Zhao B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal proteins are involved in arbuscule formation and responses to abiotic stresses during AM symbiosis. Front Microbiol. 2018;5:9–19. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunarpi T, Horie J, Motoda M, Kubo H, Yang K, Horie Yoda R, et al. Enhanced salt tolerance mediated by AtHKT1 transporter-induced Na+unloading from xylem vessels to xylem parenchyma cells. Plant J. 2005;44:928–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. The society for molecular biology and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiknia M, Skiada V, Ipsilantis I, Vasileiadis S, Kavroulakis N, Genitsaris S, Papadopoulou KK, Hart M, Klironomos J, Karpouzas DG, Ehaliotis C. Strong host-specific selection and over-dominance characterize arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal root colonizers of coastal sand dune plants of the Mediterranean region. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2021;97:fiab109. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiab109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadez V, Rodier F, Payré H, Drevon JJ. Nodules permeability to O2 and nitrogenase-linked respiration in bean genotypes varying in the tolerance of N2 fixation to P deficiency. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1996;34:871–878. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz Patto MC, Rubiales D. Lathyrus diversity: available resources with relevance to crop improvement–L. sativus and L. cicera as case studies. Annals of botany. 2014;113(6):895–908. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Sun Y, Shi Z. Arbuscular mycorrhiza enhances biomass production and salt tolerance of sweet sorghum. Microorganisms. 2019;7:289. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CL, Hanbury CD, Young P, Phillips N, Wiese SC, Milton JB, Davidson RH, Siddique KHM, Harris D. The nutritional value of Lathyrus cicera and Lathyrus sativus grain for sheep. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2012;99(1–4):45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wu QS, Zou YN, Xia RX, Wang M. Five Glomus species affect water relations of Citrus tangerine during drought stress. Botanical Studies. 2007;48:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Hamamoto S, Uozumi N. Sodium transport system in plant cells. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:410. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Zhou Y, Fan J, Fu Y, Shen L, Yao Y, Li R, Fu S, Duan R, Hu X, et al. SpBADH of the halophyte Sesuvium portulacastrum strongly confers drought tolerance through ROS scavenging in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younesi O, Moradi A. Effects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (AMF) on antioxidant enzyme activities in salt-stressed bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L) Agriculture. 2014;60(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- Yu QRZ. Waterlogging influences plant growth and activities of superoxide dismutases in narrow-leafed lupin and transgenic tobacco plants. J Plant Physiol. 1999;155:431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HX, Hodson JN, Williams JP, Blumwald E. Engineering salt-tolerant Brassica plants: characterization of yield and seed oil quality in transgenic plants with increased vacuolar sodium accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12832–12836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231476498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QH, Chao XH, Zhi BZ, et al. Changes in antioxidative enzymes and cell membrane osmosis in tomato colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizae under NaCl stress. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2007;59:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:441–445. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XC, Song FB, Liu SQ, Liu TD. Arbuscular mycorrhizae improves photosynthesis and water status of Zea mays L. under drought stress. Plant Soil Environ. 2012;58:186–191. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.