Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has proven beneficial in attenuating diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) but has been found to be a substrate of a disintegrin and metalloprotease protein-17 (ADAM17). However, whether ADAM17 plays a role in the pathogenesis and intervention of DCM is obscure. In this study, we created cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 (A17α-MHCKO) mice, and left ventricular dimension, function, pathology and molecular biology were assessed in ADAM17fl/fl control, A17α-MHCKO control, ADAM17fl/fl diabetic and A17α-MHCKO diabetic mice. Both differentiated H9c2 cells and neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were used to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of ADAM17 on DCM. The results showed that protein expression and activity of ADAM17 were upregulated whereas the protein expression of ACE2 was downregulated in the myocardium of diabetic mice. Cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 mitigated cardiac fibrosis and cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ameliorated cardiac dysfunction in mice with DCM. Bioinformatic analyses detected a number of genes enriched in metabolic pathways, in particular the AMPK signaling pathway, expressed differentially between the hearts of A17α-MHCKO and ADAM17fl/fl diabetic mice. The mechanism may involve activated AMPK pathway, increased autophagosome formation and improved autophagic flux, which reduced the apoptotic response in cardiomyocytes. In addition, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) might act as an upstream mediator of upregulated ADAM17 and ADAM17 might affect AMPK signaling via α1 A-adrenergic receptor (ADRA1A). These results indicated that ADAM17 activity and ACE2 shedding were enhanced in DCM, which was reversed by cardiomyocyte-specific ADAM17 knockout. Thus, inhibition of ADAM17 may provide a promising approach to the treatment of DCM.

Subject terms: Cardiovascular diseases, Cardiology

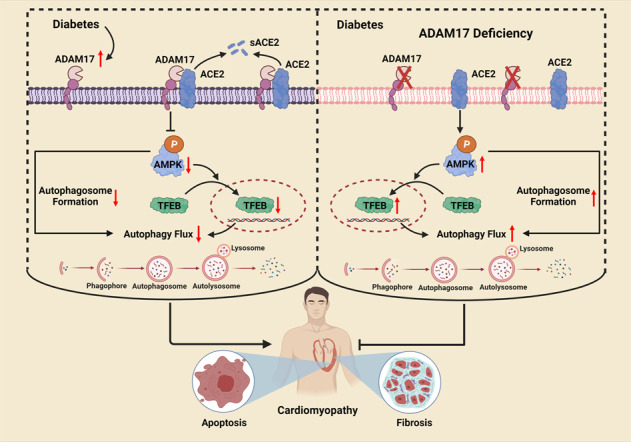

Proposed mechanisms underlying the salutary effects of ADAM17 deficiency on diabetic cardiomyopathy. ADAM17 deficiency increases autophagosome formation and improves autophagic flux via reducing ACE2 shedding, activating AMPK pathway, and promoting TFEB nuclear translocation, which reduces the apoptotic response in cardiomyocytes and attenuates left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in DCM of mice.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is on a rapid surge worldwide, and cardiovascular complications secondary to DM have emerged as a major challenge in the field of cardiovascular medicine1. A subset of diabetic patients exhibited cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction without hypertension and coronary artery disease, labeled diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM)2. However, the pathological and molecular mechanisms of DCM are yet poorly understood, hindering the development of an effective therapeutic target.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a key role in the pathogenesis of heart failure induced by many etiologies such as DCM, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and aldosterone antagonists have proven to improve cardiac remodeling and dysfunction and become the cornerstone in the pharmacological treatment of heart failure3,4. However, these classical members of RAS as therapeutic targets have inherent limitations. Angiotensin II (Ang II) produced through chymase pathway cannot be inhibited by ACEIs, and intracellular Ang II cannot be blocked by ARBs5,6. In recent years, new members of RAS, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)], Mas receptor (MasR), angiotensin-(1–9) [Ang-(1–9)] and angiotensin IV (Ang IV), in the treatment of heart failure have received an increasing attention, and research work in our and other laboratories have discovered that ACE2-Ang-(1–7)-MasR, as a new axis of RAS, played a crucial role in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases7. ACE2 degrades Ang II to Ang-(1–7) and negatively regulates RAS activation in the heart8. Our group found that local ACE2 overexpression in the myocardium ameliorated left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction via an enhanced conversion of Ang II to Ang-(1–7) in a rat model of DCM9, and chronic infusion of Ang-(1–7) improved cardiac remodeling and function by reducing myocardial fibrosis, myocardial hypertrophy and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in a rat model of DCM10. These results suggested that activation of the ACE2-Ang-(1–7)-MasR axis may provide a promising new approach to the intervention of DCM.

A disintegrin and metalloprotease protein-17 (ADAM17), by shedding >70 substrates on the cell membrane, regulates multiple cellular responses11. Previous studies demonstrated that the serum level and activity of soluble ACE2 were increased in patients with heart failure, which correlated with cardiac dysfunction12. The mechanism may involve an increased activity of ADAM17 induced by RAS activation, which leads to enhanced shedding of ACE2, as an ADAM17 substrate, from cell membrane13. An early finding that the expression of ADAM17 was markedly increased in the myocardium of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy inspired mechanistic studies in animal models14,15. However, results from experimental studies regarding the role of ADAM17 in cardiomyopathy were highly controversial. ADAM17 inhibition with small-interfering RNA prevented myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis in Ang II-induced hypertensive mice as well as spontaneously hypertensive rats16. However, cardiomyocyte-specific ADAM17 knockdown was reported to aggravate cardiac hypertrophy by reducing integrin β1 cleavage in mice after transverse aortic constriction17. In mice with acute myocardial infarction, cardiomyocyte-specific knockdown of ADAM17 exacerbated left ventricular dilation and dysfunction by limiting the transcription of VEGFR2 as well as angiogenesis18. These contradictive results suggested that ADAM17 knockdown is a double-edged sword and plays a beneficial role only in conditions where RAS is highly activated. Hereto, there has been no study to report the therapeutic effects and underlying mechanisms of ADAM17 deficiency on DCM. As a wealth of evidence indicates that RAS is highly activated in DCM19,20, a series of in vivo and in vitro experiments were designed and performed to examine the effect of ADAM17 on the pathogenesis and treatment of DCM. This study provides a novel insight into the pathogenesis of and a promising therapeutic target for DCM. We created cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 (A17α-MHCKO) mice with or without diabetes and assessed left ventricular dimension, function, pathology and molecular biology in four groups of mice: ADAM17fl/fl control, A17α-MHCKO control, ADAM17fl/fl diabetic and A17α-MHCKO diabetic mice. We found that cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 mitigated cardiac fibrosis and cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ameliorated cardiac dysfunction in mice with DCM. We explored the mechanism underlying these beneficial effects, which may involve activated AMPK pathway, increased autophagosome formation and improved autophagic flux, which reduced the apoptotic response in cardiomyocytes. These results suggested that inhibition of ADAM17 may provide a promising approach to the treatment of DCM.

Results

Body weight, blood glucose and serum lipid profile

Body weight (BW), fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) were remarkably higher in A17fl/fl DM group mice relative to those in the A17fl/fl control group. By comparison, BW, FBG, and serum lipid levels did not differ between the A17α-MHCKO DM and littermate A17fl/fl DM group (Supplementary Table 1).

Myocardial ADAM17 expression and activity were increased in diabetic hearts

Compared with controls, diabetic hearts showed markedly upregulated ADAM17 mRNA and protein expressions (Supplementary Fig. S2a–c) as well as an increased ADAM17 enzymatic activity (Supplementary Fig. S2d). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed more intensive staining of ADAM17 in the myocardium of diabetic mice than in control mice (Supplementary Fig. S2e, f). Besides, we used co-immunofluorescence staining to display ADAM17 expression in different cardiac cells and found that ADAM17 was abundantly expressed in cardiomyocytes, but sparsely expressed in fibroblasts and endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. S2g).

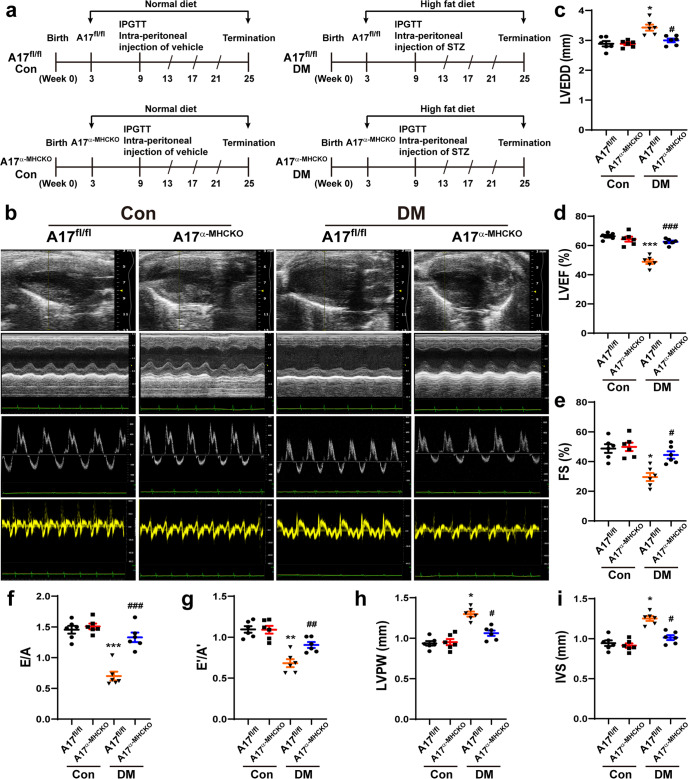

Cardiac remodeling and function were improved in A17α-MHCKO diabetic mice

Echocardiographic measurements of LVEDD, LVPW, and IVS were increased whereas LVEF, FS, E/A, and E’/A’ were decreased in the A17fl/fl DM group compared with the A17fl/fl control group (Fig. 1b–i). However, these echocardiographic values were all reversed in the A17α-MHCKO DM group as compared with the A17fl/fl DM group. Thus, cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 ameliorated left ventricular remodeling and rescued systolic and diastolic function in diabetic mice (Fig. 1b–i).

Fig. 1.

Experiment timeline and echocardiographic measurements in four groups of mice. a Experiment timeline in four groups of mice. b Representative echocardiographic images in mice: (1) Two-dimensional echocardiogram showing left ventricular long-axis view; (2) M-mode echocardiogram showing left ventricular dimensions; (3) Pulse-wave Doppler echocardiogram depicting diastolic mitral flow; (4) Tissue Doppler echocardiogram displaying mitral annular velocities. c Measurements of left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) in mice. d Measurements of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in mice. e Measurements of left ventricular fractional shortening (FS) in mice. f Measurements of the ratio of early to late diastolic mitral flow velocities (E/A) in mice. g Measurements of the ratio of early to late diastolic mitral annular velocities (E'/A') in mice. h Measurements of left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) thickness in mice. i Measurements of interventricular septum (IVS) thickness in mice. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group; n = 6.

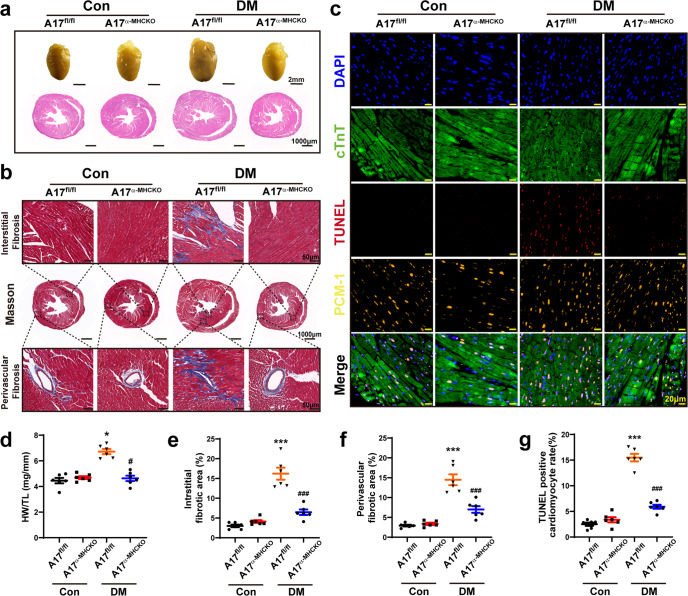

Myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis were attenuated in A17α-MHCKO diabetic mice

Relative to the A17fl/fl control group, the HW/TL ratio was upregulated in the A17fl/fl DM group, whereas the HW/TL ratio in the A17α-MHCKO DM group was downregulated relative to the A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 2a, d). In comparison with the A17fl/fl control group, perivascular and interstitial fibrosis area in the myocardium displayed by Masson’s trichrome staining was substantially increased in the A17fl/fl DM group, but significantly decreased in the A17α-MHCKO DM mice group, relative to the littermate A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 2b, e, f). In order to assess the role of cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis, TUNEL staining together with staining of cardiomyocyte-specific marker cTnT and PCM-1 were performed. The proportion of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cardiomyocytes in the myocardium was markedly reduced in the A17α-MHCKO DM group versus the littermate A17fl/fl DM group mice (Fig. 2c, g).

Fig. 2.

Histological and immunohistochemical staining in four groups of mice. a Representative images of hearts and myocardial cross-sections in four groups of mice: representative heart pictures (scale bar: 2 mm) were shown in the upper panel; Representative H&E staining of myocardial cross-sections (scale bar: 1000 μm) were shown in the lower panel. b Representative Masson’s trichrome staining of myocardial fibers. Masson’s trichrome staining of cardiac short-axis cross sectional areas (scale bar: 1000 μm) were shown in the middle panel. Dotted boxes in the middle panel indicated a local area in the low magnification field (scale bar: 1000 μm), which was enlarged in the high magnification field (scale bar: 50 μm) in the bottom panel. The interstitial fibrosis images were shown in the top panel and the perivascular fibrosis images were shown in the bottom panel. c Representative TUNEL-positive cardiomyocyte staining in mice (scale bar: 20 μm). d Quantitative analysis of heart weight/tibial length (HW/TL) ratio in mice, n = 6. e and f Quantification of the interstitial and perivascular fibrosis area in mice, n = 6. g Quantification of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes in mice, n = 6. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group.

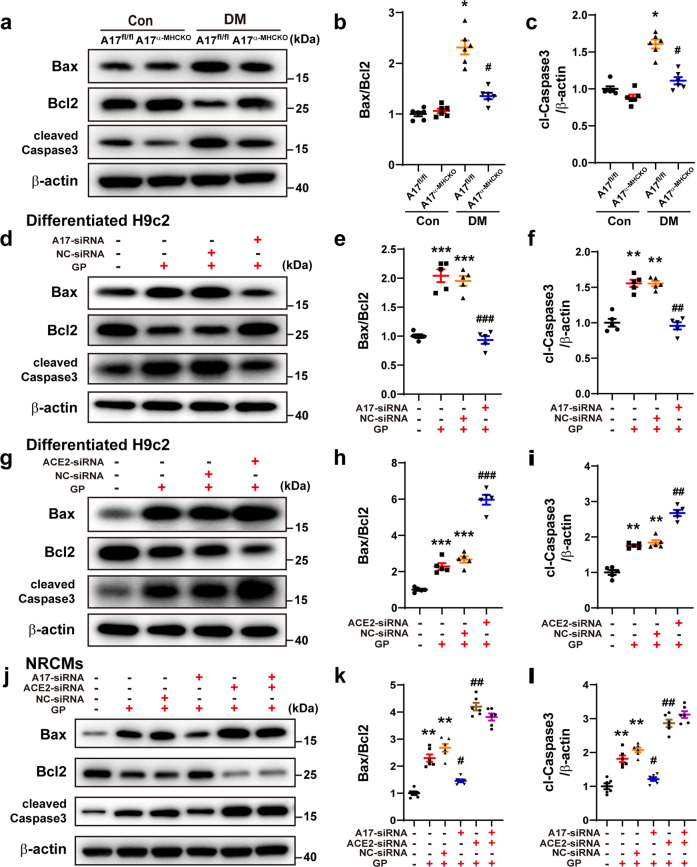

To further evaluate the effect of cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 on apoptosis in the myocardium, the levels of Bax, Bcl2 and cleaved caspase-3 protein expression in the myocardium tissue were measured, which showed a significant downregulation in the A17α-MHCKO DM group compared with A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 3a–c). Thus, cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 alleviated myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis in diabetic mice. In the in vitro experiment, the protein expression levels of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase-3 were detected in the differentiated H9c2 cells and neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs), which were markedly downregulated in the ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the NC-siRNA group (Fig. 3d–f, Fig. 3j–l).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ADAM17 and ACE2 on apoptosis in mice, differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs. a Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase-3 expression in the myocardium of four groups of mice. b, c Quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2 and cleaved caspase-3 expression in four groups of mice, n = 6. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; #P < 0.05 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group. d–f Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase three expression and quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2 and cleaved caspase three expression in four groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA, respectively. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. g–i Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase-3 expression and quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2 and cleaved caspase-3 in four groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ACE2-siRNA, respectively. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group. j Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase-3 expression in six groups of NRCMs treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA, GP + ADAM17-siRNA, GP + ACE2-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA+ACE2-siRNA, respectively. k, l Quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2 and cleaved caspase-3 expression in six groups of NRCMs. Mean values were derived from six independent experiments. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group.

The undifferentiated and differentiated H9c2 cells showed two distinct features: First, H9c2 cells cultured in a medium containing 10% FBS presented a myoblast phenotype, with a mononucleated and spindle-to-stellate shape (Supplementary Fig. S3g). In contrast, H9c2 cells growing in the medium containing 1% FBS plus 1 μM RA for 7 days showed cell fusion and formation of more elongated multinucleated cells (Supplementary Fig. S3g), as described previously21,22. Second, differentiated H9c2 cells cultured in a 1% FBS media plus RA exhibited increased expression of cardiac-specific markers including cardiac troponin I and MYH6 (Supplementary Fig. S3h–k).

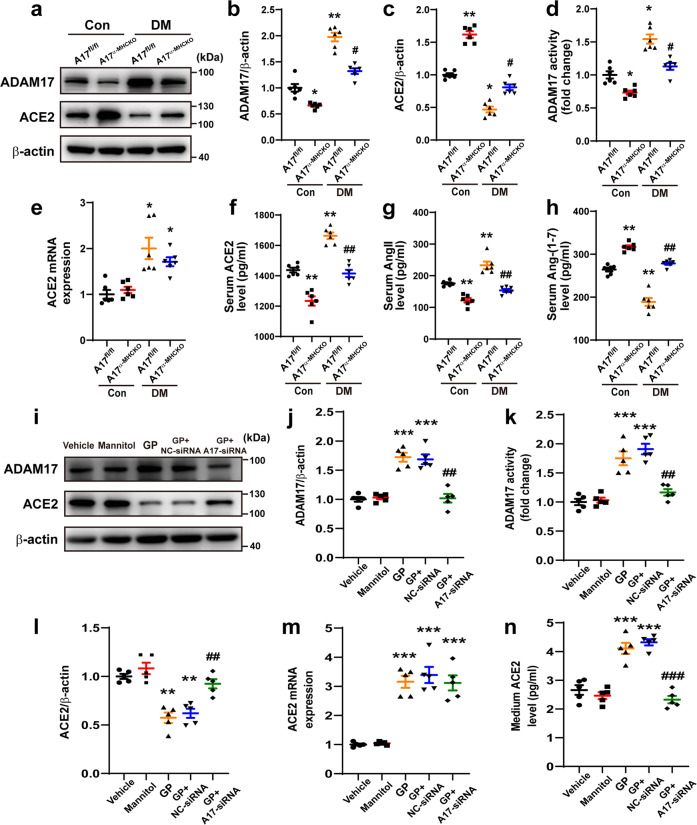

ADAM17 was essential for cleaving ACE2 in vivo and in vitro

To explore the cleaving function of ADAM17, we examined mRNA levels of substrates of ADAM17 (TNF-α, TNF-αRI, TNF-αRII, IL-6, IL-6R, ALCAM, AREG, ERBB4, TGF-α, ICAM, VCAM, and ACE2) in the myocardium of diabetic and normal control mice (Supplementary Fig. S4a–l). ACE2 mRNA expression level was markedly upregulated in the myocardium of DCM mice, whereas the rest substrates did not differ in mRNA expression level between the two groups, suggesting that activated RAS is of paramount importance in the pathogenesis of DCM. The protein expression and activity of ADAM17 were downregulated in the myocardium of A17α-MHCKO DM group as compared with the A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 4a, b, d), whereas the protein expression of ACE2 was upregulated in the myocardium of A17α-MHCKO DM group compared with the A17fl/fl DM group mice (Fig. 4a, b, c). Although ACE2 mRNA level was increased in DM mice than normal control, ADAM17 did not affect ACE2 mRNA expression in these mice (Fig. 4e), suggesting that ADAM17 affects only post-transcriptional expression level of ACE2.

Fig. 4.

Serum levels of ACE2, Ang II, and Ang-(1–7) in mice and expression of ADAM17 and ACE2 in the myocardium of mice and in differentiated H9c2 cells. a Representative Western blot images of ADAM17 and ACE2 protein expression in the myocardium of four groups of mice. b, c Quantitative analyses of ADAM17 and ACE2 expression in the myocardium of mice, n = 6. d Quantitative analysis of ADAM17 activity in the myocardium of mice, n = 6. e Quantitative analysis of ACE2 mRNA expression in the myocardium of mice, n = 6. f–h Quantitative analysis of serum levels of ACE2, Ang II, and Ang-(1–7) in mice, n = 6. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group. i, j and l Representative Western blot images and quantitative analysis of ADAM17 and ACE2 protein expression in five groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, mannitol, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA, respectively. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. k Quantitative analysis of ADAM17 activity in five groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated as above. m, n Quantitative analysis of ACE2 mRNA level and ACE2 expression in the medium in five groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated as above. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group.

ADAM17, as a negative regulator of RAS, mediates shedding of ACE2 from cell membrane and produces a soluble form of ACE213. Thus, we detected the serum levels of ACE2, Ang II, and Ang-(1–7) in the in vivo experiment. In comparison with the A17fl/fl control group, the soluble ACE2 level in the serum was markedly increased in A17fl/fl DM group probably due to the increased expression and activity of ADAM17 in the myocardium. As a consequence of increased cleaving of ACE2, serum Ang II level was increased and serum Ang-(1–7) level was decreased in the A17fl/fl DM group versus the A17fl/fl control group (Fig. 4f–h). Conversely, the serum Ang II level was decreased while serum Ang-(1–7) level was increased in the A17α-MHCKO DM group compared with the A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 4f–h). These results substantiated the key role of ADAM17 in regulating the ACE2-Ang II/Ang-(1–7) axis.

To further validate these in vivo results, differentiated H9c2 cells were treated with normal glucose, mannitol, GP, NC-siRNA, and ADAM17-siRNA, which showed that ADAM17 protein expression and activity were higher in the GP group than the mannitol group (Fig. 4i–k). In contrast, ACE2 protein expression was markedly lower in the GP group than the mannitol group, whereas ACE2 protein expression was markedly higher in the GP + ADAM17-siRNA group than the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 4I, l). However, the mRNA level of ACE2 was increased with GP treatment, which was not affected by ADAM17-siRNA treatment (Fig. 4m), a finding in line with our in vivo results. The increased level of ACE2 in the culture medium after GP treatment as compared with the mannitol group was substantially suppressed with ADAM17-siRNA treatment (Fig. 4n), indicating that ADAM17 may cleave ACE2 into the medium.

To further assess whether ACE2 was connected with the effect of ADAM17 on apoptotic response, the related indicators of apoptosis were measured in differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs. The Bax/Bcl2 ratio and cleaved caspase-3 expression levels were increased by GP treatment, which was further elevated in the GP + ACE2-siRNA group (Fig. 3g–i). These results were opposite to that after ADAM17 knockdown (Fig. 3j–l). However, when gene knockdown of both ADAM17 and ACE2 were performed, the related indicators of apoptosis had no significant change as compared with ACE2-siRNA treatment alone (Fig. 3j–l). These results clearly indicated that cleaving ACE2 is an important function of ADAM17 and ACE2 plays a significant role in the effect of ADAM17 on apoptotic response.

Metabolic pathway genes differentially expressed between A17α-MHCKO and ADAM17fl/fl diabetic mice

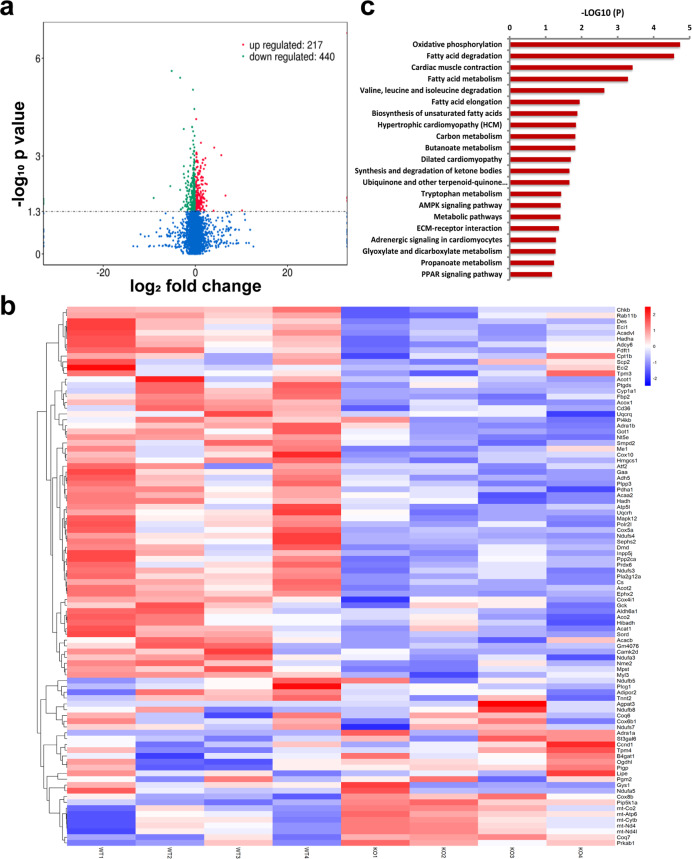

To obtain a comprehensive view of transcriptome changes associated with deficiency of ADAM17 in cardiomyocytes, we performed RNA sequencing from myocardial tissues isolated from the A17fl/fl DM and A17α-MHCKO DM mice. The results revealed that 217 genes were upregulated and 440 genes downregulated in the myocardium of the A17α-MHCKO DM versus A17fl/fl DM mice (Fig. 5a). The top 50 genes differentially expressed in the two groups of mice were depicted (Fig. 5b), which according to KEGG categories, involved oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid degradation, cardiac muscle contraction, fatty acid metabolism, and AMPK signaling (Fig. 5c). In particular, we focused on the AMPK signaling pathway because of its central role in regulating glucose, lipid homeostasis and autophagy, and also because of a recent finding that AMPK served as a point of balance between physiological and pathological functions of the RAS23.

Fig. 5.

RNA-sequencing analysis of myocardial tissues in mice. a Volcano plot showing the transcript expression profiles in the hearts of A17α-MHCKO and ADAM17fl/fl diabetic mice, respectively. The horizontal line marked the threshold (P < 0.05) for defining upregulated (red dot) or downregulated (blue dot) genes in the myocardium of A17α-MHCKO diabetic mice. The x-axis indicated log2 fold change and the y-axis indicated −log10 P-values. b Hierarchical clustering of the top 50 (ranked by P-values) genes differentially expressed in hearts from the A17α-MHCKO and ADAM17fl/fl diabetic mice. c KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differential expression (DE) transcripts in the heart. The DE transcripts falling into the top pathways were summarized. The x-axis indicated –log10 (P-values) of the pathway and the y-axis displayed functional pathways

ADAM17 regulated myocardial AMPK/mTOR pathway and TFEB expression in vivo and in vitro

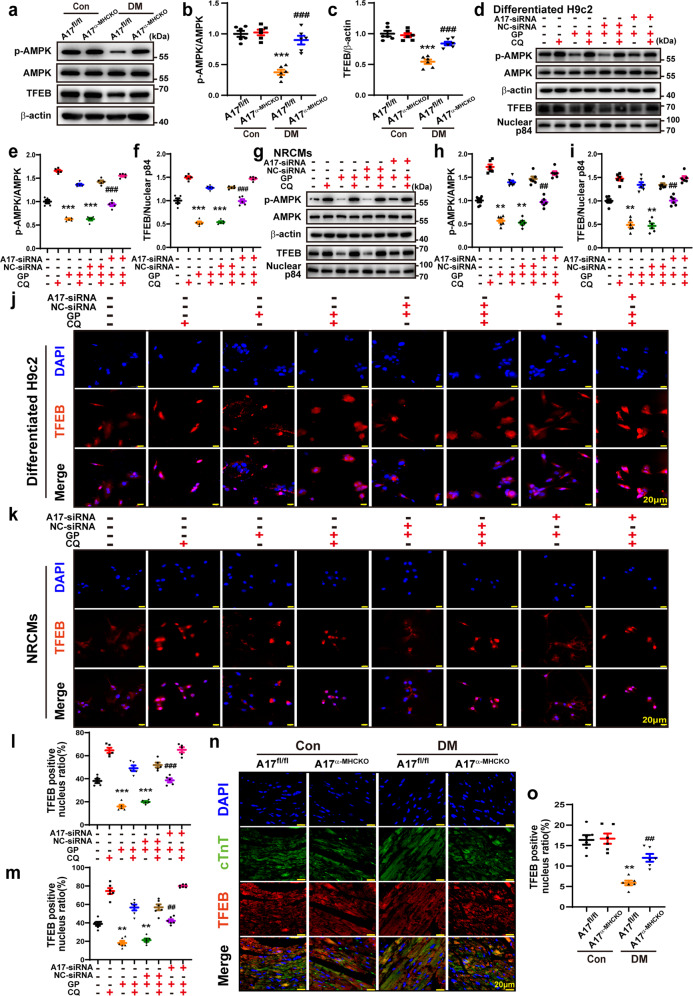

We found that ADAM17 deficiency reversed diabetes-induced inactivation of the AMPK pathway. The levels of AMPK phosphorylation and TFEB protein expression were remarkably decreased in the A17fl/fl DM mice relative to the A17fl/fl control mice whereas cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 significantly increased AMPK phosphorylation and TFEB protein levels in the A17α-MHCKO DM mice (Fig. 6a–c). We future investigated the relationship between ADAM17 and AMPK phosphorylation after GP treatment in both differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs. The level of AMPK phosphorylation was dramatically decreased in the differentiated H9c2 cells of GP group relative to the control group, but returned to the level of the control group in the ADAM17 knockdown group (Fig. 6d–f). The results in NRCMs were consistent with those in differentiated H9c2 cells (Fig. 6g–i). Taken together, the results in vitro showed similar changes to those in vivo. Thus, ADAM17 played a critical role in the regulation of the AMPK signaling pathway in DCM. As TFEB drives the expression of autophagy and lysosomal genes24 and activation of AMPK may promote TFEB nuclear translocation25, we further examined whether ADAM17 affects lysosome function via TFEB nuclear translocation. The nuclear TFEB protein expression level was markedly decreased in the differentiated H9c2 cells of the GP group relative to the vehicle group (Fig. 6d, f), which was restored in the ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the NC-siRNA group. The results in NRCMs were consistent with those in differentiated H9c2 cells (Fig. 6g, i). In immunofluorescence analysis, TFEB nuclear translocation was significantly reduced in the GP group as compared with the vehicle group, but was virtually normalized in the ADAM17-siRNA group versus the NC-siRNA group (Fig. 6j–m). Thus, TFEB nuclear translocation was inhibited by GP treatment but enhanced by ADAM17 knockdown in both differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs. In addition, we examined TFEB nuclear translocation in myocardial tissues in four groups of mice, which showed similar results to those in the in vitro experiments (Fig. 6n, o).

Fig. 6.

ADAM17 regulated the AMPK-TFEB pathway in vivo and in vitro. a Representative Western blot images of protein expression of phosphorylated AMPK, AMPK, and TFEB in the myocardium of four groups of mice. b, c Quantitative analysis of phosphorylated AMPK/AMPK and TFEB expression in the myocardium of four groups mice, n = 6. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; ###P < 0.001 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group. d–f Representative Western blot images and quantitative analysis of phosphorylated AMPK, AMPK, and TFEB protein expression in eight groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA, and GP + ADAM17-siRNA, with and without additional chloroquine (CQ) treatment, respectively. Mean values were obtained from five independent experiments. g–i Representative Western blot images and quantitative analysis of phosphorylated AMPK, AMPK, and TFEB protein expression in eight groups of NRCMs treated as above. j Representative immunofluorescence staining of TFEB (red) in eight groups of differentiated H9c2 cells (scale bar: 20 μm) treated as above. k Representative immunofluorescence staining of TFEB (red) in eight groups of NRCMs treated as above (scale bar: 20 μm). l Quantification of TFEB-positive nucleus ratio in differentiated H9c2 cells. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. m Quantification of TFEB-positive nucleus ratio in NRCMs. Six independent experiments were performed to derive the mean values. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group. n Representative immunofluorescence staining of TFEB and cTnT in four groups of mice (scale bar: 20 μm). o Quantification of TFEB-positive nucleus ratio in cardiomyocytes of four groups of mice, n = 6. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group

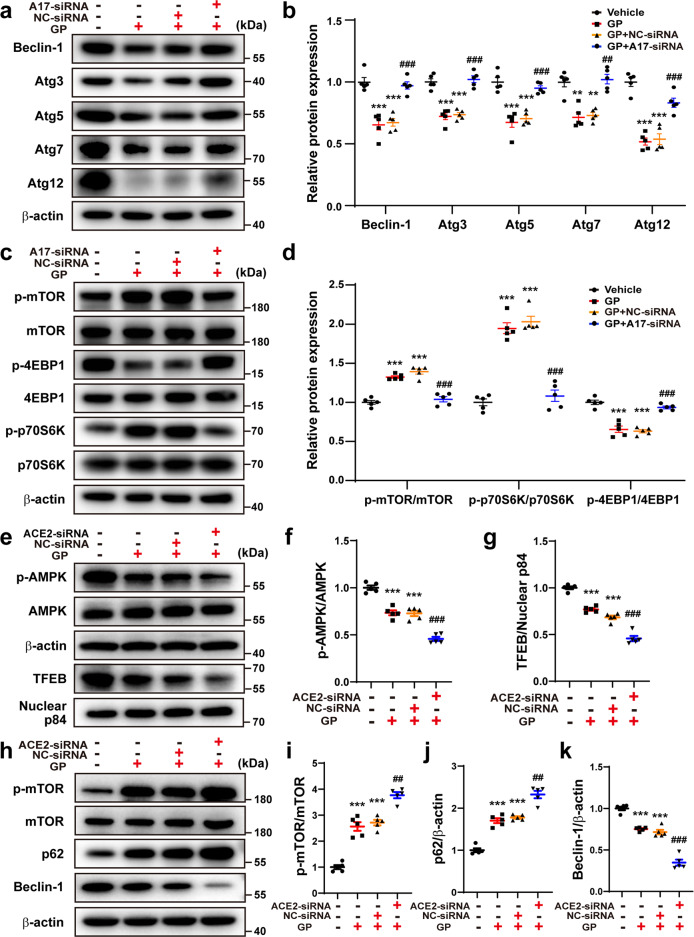

The AMPK pathway regulates metabolic process, protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and autophagy via targeting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)26. Thus, to assess the effect of ADAM17 on the AMPK/mTOR pathway in cardiac autophagy, the mTOR pathway and its downstream activity, such as phosphorylated 4EBP1 (p-4EBP1) and phosphorylated p70S6K (p-p70S6K), were measured in differentiated H9c2 cells. Relative to the vehicle group, the protein expression of phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) and p-p70S6K was significantly increased in the GP group, which was reversed in the ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the NC-siRNA group (Fig. 7c, d). Thus, the role of ADAM17 in the expression of AMPK and mTOR was opposite and consistent with previous data26. In addition, p-4EBP1 expression level was decreased in the GP group relative to the vehicle group, but was increased in the ADAM17-siRNA group versus the NC-siRNA group (Fig. 7c, d). It indicated that ADAM17 played a crucial role in the AMPK/mTOR signal pathway via regulating 4EBP1 and p70S6K protein phosphorylation.

Fig. 7.

Effects of ADAM17 or ACE2 deficiency on autophagy-related proteins. a, b Representative Western blot images and quantitative analyses of protein expression of Beclin1, Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, and Atg12 in four groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA, respectively. c, d Representative Western blot images and analysis of phosphorylated mTOR, mTOR, phosphorylated p70S6K, p70S6K, phosphorylated 4EBP1 and 4EBP1 protein expression in differentiated H9c2 cells treated as above. Mean values were derived from 5 independent experiments. e–g Representative Western blot images and quantitative analysis of phosphorylated AMPK, AMPK, and TFEB protein expression in differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ACE2-siRNA, respectively. h–k Representative Western blot images and analysis of phosphorylated mTOR, mTOR, p62 and Beclin1 protein expression in differentiated H9c2 cells treated as above. Mean values were obtained from five independent experiments. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group

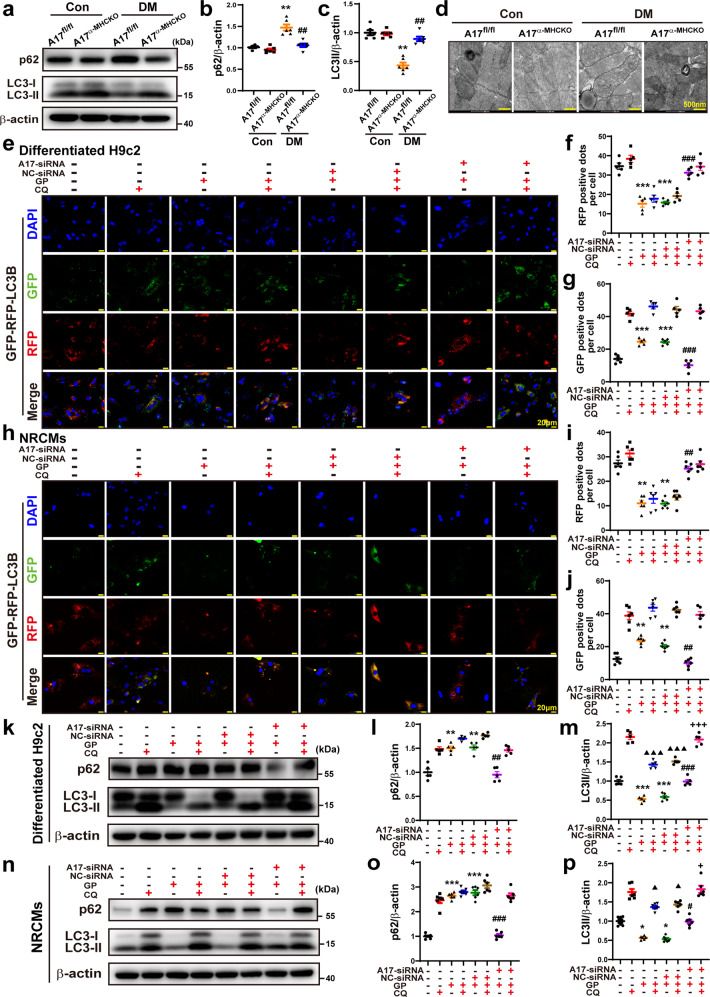

ADAM17 deficiency upregulated autophagy in vivo and in vitro

AMPK-induced autophagy has been shown to attenuate the development of DCM27. In the process of lysosome degradation, p62 is degraded by proteolytic enzymes and an elevated level of p62 expression is generally considered to suggest the inhibition of autophagy activity28. We further examined whether autophagy was affected by ADAM17. Relative to the A17fl/fl control group, the protein expression of p62 was increased in A17fl/fl DM group, which was decreased in A17α-MHCKO DM mice (Fig. 8a, b). In the in vitro experiment, p62 expression was downregulated in the ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the NC-siRNA group in both differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs (Fig. 8k–o). We also measured the ratio of LC3II/β-actin levels in vivo and in vitro. In the in vitro experiment, the LC3II/β-actin ratio was decreased in A17fl/fl DM group as compared with the control group and returned to control levels in the A17α-MHCKO DM group (Fig. 8a–c). In the in vitro experiment, the LC3II expression level was markedly upregulated in the ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the NC-siRNA group in both differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs (Fig. 8k–p). Transmission electron microscopy showed apparent swelling, vacuolation and myofibril disarray in the diabetic myocardium, which were ameliorated by cardiomyocyte-specific ADAM17 knockout (Fig. 8d).

Fig. 8.

Effects of ADAM17 deficiency on cardiomyocyte autophagy in vivo and in vitro and on autophagic flux in differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs. a Representative Western blot images of autophagy-related protein expression, including p62 and LC3 in the myocardium of four groups of mice. b, c Quantitative analysis of protein expression of p62 and LC3II/β-actin in the myocardium of four groups of mice, n = 6. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, vs. the A17fl/fl control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group. d Representative transmission electron microscopy images of the myocardium in four groups of mice (scale bar: 500 nm). e Representative fluorescence images of green fluorescent protein (GFP; green), red fluorescent protein (RFP; red), GFP-RFP-LC3 (merged: yellow) and nuclei stained with DAPI (scale bar: 20 μm) in eight groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA, with and without additional CQ treatment, respectively. f, g Quantitative analysis of RFP-positive and GFP-positive dots per cell in differentiated H9c2 cells. Mean values were derived from five independent experiments. h Representative fluorescence images of GFP-RFP-LC3 in eight groups of NRCMs treated as above. i, j Quantitative analysis of RFP-positive and GFP-positive dots per cell in NRCMs. Mean values were obtained from six independent experiments. k Representative Western blot images of p62 and LC3 protein expression in eight groups of differentiated H9c2 cells treated as above. l and m Quantitative analysis of protein expression of p62 and LC3II/β-actin in differentiated H9c2 cells. Five independent experiments were performed to calculate the means. n Representative Western blot images of p62 and LC3 protein expression in eight groups of NRCMs treated as above. o and p Quantitative analysis of protein expression of p62 and LC3II/β-actin in NRCMs. Mean values were derived from six independent experiments. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group; ▲P < 0.05, ▲▲▲P < 0.001 vs. the CQ group; +P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001 vs. the GP + CQ + NC-siRNA group

ADAM17 deficiency increased autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes

Analysis of autophagic flux rate is a key approach to measuring autophagy29. As a lysosomal acidification inhibitor to block the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome, CQ can cause autophagosome accumulation30. As ADAM17 played a crucial role in autophagy in cardiomyocytes, we further examined the role of ADAM17 in autophagosome turnover by treating differentiated H9c2 cells and NRCMs in the presence of either vehicle or CQ. Autophagic flux was imaged by fluorescence-tagged LC3B puncta in cells, where GFP-tagged LC3B indicates autophagic flux and RFP-tagged LC3B indicates autolysosomes30. As GFP is pH sensitive and quenched within the acidic environment of the lysosome, increased green fluorescence dots represent a blocked autophagic flux whereas increased red fluorescence dots reflect productive autophagosomes. In immunofluorescence analysis, RFP dots were markedly decreased in the GP group relative to the vehicle group, which was markedly reversed in the GP + ADAM17-siRNA group compared with the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 8e, f). In contrast, GFP dots were increased in the GP group versus the vehicle group, which was reversed to the control level in the GP + ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 8e, g). These results suggested that autophagic flux was inhibited by GP treatment and restored by ADAM17 knockdown.

As CQ blocks autophagic flux by inhibiting the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome, a late stage of autophagic flux, RFP dots showed no significant difference between two cell subgroups receiving vehicle and CQ treatment in each of the vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA groups of differentiated H9c2 cells (Fig. 8e, f). In contrast, GFP dots were dramatically increased in the cell subgroup receiving CQ versus the subgroup receiving vehicle treatment in each of the four cell groups (Fig. 8g). Similar results were obtained in NRCMs (Fig. 8h–j). These results indicated that ADAM17 may inhibit autophagic flux at an early stage by attenuating the formation of autophagosome.

Effect of ADAM17 or ACE2 deficiency on autophagosome formation-related proteins

In order to further assess whether ADAM17 affects the formation of autophagosome, the protein expression levels of Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12 and Beclin-1, which were associated with the process of autophagosome formation, were measured in differentiated H9c2 cells. Protein expression levels of Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12 were markedly downregulated in the GP group compared with the vehicle group, which was reversed in GP + ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 7a, b). Beclin-1 protein expression showed similar changes in these cell groups (Fig. 7a, b).

To elucidate the effect of ACE2 on ADAM17-mediated autophagy, the autophagy-related proteins were measured in differentiated H9c2 cells treated with GP, GP + GP + NC-siRNA and GP + ACE2-siRNA. Relative to the GP + NC-siRNA group, protein expression level of p-AMPK, TFEB and beclin1 were decreased in the GP + ACE2-siRNA group. In contrast, the protein expression levels of p-mTOR and p62 were increased in the GP group relative to the vehicle group, which was further upregulated in the GP + ACE2-siRNA group versus the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 7e–k). These results were opposite to those in cells with ADAM17 knockdown and indicated that ACE2 played an indispensable role in the effect of ADAM17 on cardiac autophagy.

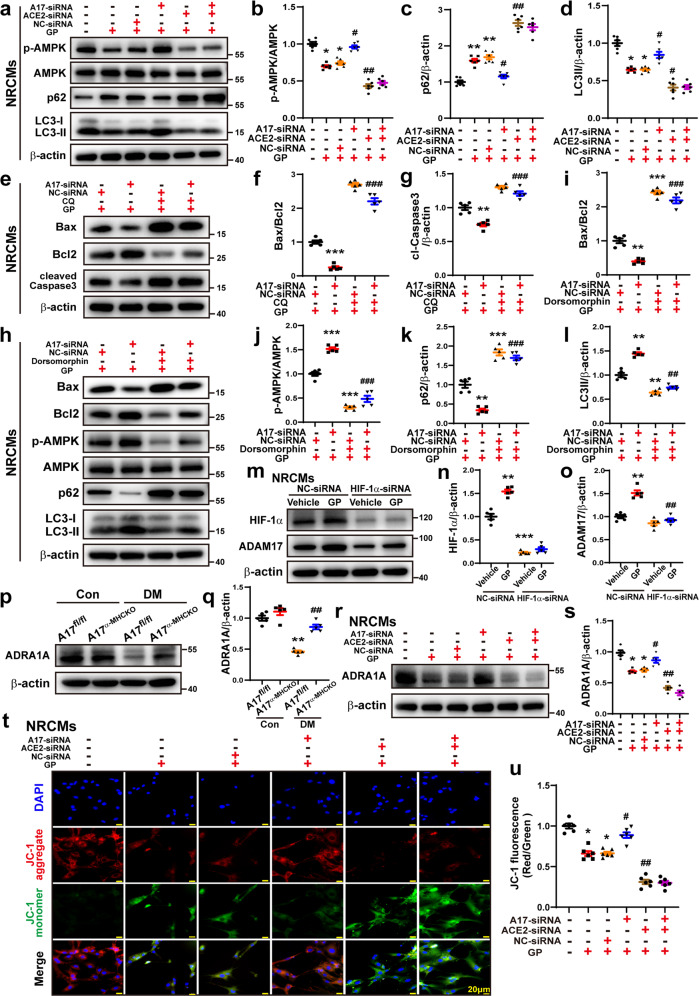

Effect of ADAM17 and ACE2 double-knockdown on cardiac apoptosis and autophagy

In order to further ascertain the effect of ADAM17 and ACE2 on cardiac apoptosis and autophagy, double-knockdown of ADAM17 and ACE2 was performed in NRCMs. The ratio of Bax/Bcl2 and protein expression of cl-caspase 3 showed no significant difference between GP + ACE2-siRNA and GP + ACE2 + A17-siRNA groups of NRCMs (Fig. 3j–l). Similarly, protein expression of p-AMPK, p62, and LC3II exhibited no difference between GP + ACE2-siRNA and GP + ACE2 + A17-siRNA groups of NRCMs (Fig. 9a–d). These results confirmed that ACE2 is a downstream mediator of ADAM17 and double knockdown of ADAM17 and ACE2 offered no extra effects over knockdown of ACE2 alone on cardiac apoptosis and autophagy.

Fig. 9.

Effects of ADAM17 and ACE2 double knock-down and AMPK inhibitor on cardiac autophagy and apoptosis. a Representative Western blot images of protein expression of phosphorylated AMPK, AMPK, p62 and LC3 in six groups of NRCMs treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA, GP + ADAM17-siRNA, GP + ACE2-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA+ACE2-siRNA, respectively. b–d Quantitative analysis of p-AMPK/AMPK, p62 and LC3II/β-actin expression in six groups of NRCMs. Mean values were derived from six independent experiments. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group. e Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved Caspase-3 expression in four groups of NRCMs treated with GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle, GP + ADAM17-siRNA+vehicle, GP + NC-siRNA+CQ and GP + ADAM17-siRNA+CQ, respectively. f, g Quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2, and cleaved Caspase-3 expression in four groups of NRCMs. Five independent experiments were conducted to derive the means. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle group; ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + A17-siRNA group+vehicle group. h Representative Western blot images of Bax, Bcl2, p-AMPK, AMPK, p62 and LC3 expression in four groups of NRCMs treated with GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle, GP + ADAM17-siRNA+vehicle, GP + NC-siRNA+dorsomorphin, GP + ADAM17-siRNA+dorsomorphin, respectively. i–l Quantitative analysis of Bax/Bcl2, p-AMPK/AMPK, p62 and LC3II/β-actin expression in four groups of NRCMs. Mean values were derived from six independent experiments. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle group; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the GP + A17-siRNA group+vehicle group. m Representative Western blot images of HIF-1α and ADAM17 expression in four groups of NRCMs treated with vehicle+NC-siRNA, GP + NC-siRNA, vehicle+ HIF-1α-siRNA and GP + HIF-1α-siRNA, respectively. n, o Quantitative analysis of HIF-1α and ADAM17 expression in four groups of NRCMs. Five independent experiments were performed to calculate the means. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle+NC-siRNA group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group. p, q Representative Western blot images and analysis of ADRA1A protein expression in the myocardium of four groups of mice, n = 5. **P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the A17fl/fl DM group. r, s Representative Western blot images and quantitative analysis of ADRA1A protein expression in NRCMs treated with vehicle, GP, GP + NC-siRNA, GP + ADAM17-siRNA, GP + ACE2-siRNA and GP + ADAM17-siRNA+ACE2-siRNA, respectively. Five independent experiments were conducted to derive the means. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group. t and u Representative fluorescence images of JC-1 staining in NRCMs treated as above (scale bar: 20 μm). Quantitative analysis of JC-1 (JC-1 aggregates/JC-1 monomers) in NRCMs. Six independent experiments were performed to derive the mean values. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the vehicle group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the GP + NC-siRNA group

To further clarify the effect of ADAM17 on apoptosis when the autophagic flux was inhibited, CQ was used to block the autophagic flux in the in vitro experiments in NRCMs. The ratio of Bax/Bcl2 and the protein expression level of cleaved caspase-3 were markedly decreased in GP + ADAM17-siRNA + vehicle group compared with the GP + NC-siRNA + vehicle group. However, when the autophagic flux was inhibited by CQ, the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 and the protein expression levels of cleaved caspase3 were markedly increased in GP + ADAM17-siRNA+CQ groups relative to GP + ADAM17-siRNA + vehicle group (Fig. 9e–g), indicating that ADAM17 knockdown in NRCMs reduced the apoptotic response via ameliorating the autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes.

ADAM17 deficiency enhanced cell viability and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

To evaluate the role of ADAM17 and ACE2 deficiency in cell viability, CCK8 assays were performed, which showed that the level of cell viability in the GP group was markedly reduced relative to the vehicle group, which was virtually reversed in the GP + ADAM17-siRNA group relative to the GP + NC-siRNA group. Notably, relative to the GP + NC-siRNA group, the cell viability level was further decreased in the GP + ACE2-siRNA group (Supplementary Fig. S5a, b).

JC-1 fluorescent probe is commonly used to detect MMP level, which is reflected by the ratio of red/green fluorescence. The MMP level was markedly lower in the GP group than the vehicle group, which was reversed by ADAM17 knockdown but resumed by ACE2 knockdown without additional effect of combined knockdown of ADAM17 and ACE2 (Fig. 9t–u).

Effect of ADAM17 on ADRA1A/AMPK-mediated cardiac apoptosis and autophagy

In order to further clarify the role of AMPK in the impact of ADAM17 on apoptosis and autophagy, dorsomorphin, a selective AMPK inhibitor, was used in the in vitro experiments in NRCMs. The ratio of Bax/Bcl2 and the protein expression level of p62 were markedly upregulated whereas the expression levels of p-AMPK and LC3II were downregulated in GP + NC-siRNA + dorsomorphin group relative to the GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle group. These results were opposite to those in the GP + NC-siRNA+vehicle and GP + A17-siRNA+vehicle groups. However, the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 and the expression levels of p-AMPK, p62 and LC3II showed no significant difference between GP + NC-siRNA+dorsomorphin and the GP + A17-siRNA+dorsomorphin groups (Fig. 9h–l), indicating that ADAM17 knockdown in NRCMs suppresses cell autophagy and apoptosis via AMPK signaling pathway.

As shown by our results of RNA sequencing, there was a significant difference in the α1A-adrenergic receptor (ADRA1A) mRNA levels between myocardium samples of A17α-MHCKO DM and the A17fl/fl DM mice, and ADRA1A is involved in the AMPK signaling pathway according to KEGG categories (Fig. 5). As an upstream protein of AMPK, ADRA1A exerts a regulatory effect on the activity of AMPK31. To explore whether ADAM17 affected AMPK via ADRA1A, the protein expression levels of ADRA1A were measured in vivo and in vitro. ADRA1A protein expression was markedly lower in the A17fl/fl DM group than in the A17fl/fl control group, which was reversed in the A17α-MHCKO DM relative to the A17fl/fl DM group (Fig. 9p, q). The results in vitro showed similar changes in NRCMs (Fig. 9r, s).

Previous studies reported that high glucose upregulated ADAM17 through HIF-1α32, which was tested in the current study. The protein expression levels of both HIF-1α and ADAM17 levels were significantly increased in the GP + NC-siRNA group in comparison with the vehicle+NC-siRNA group in NRCMs. However, the protein expression levels of ADAM17 were dramatically decreased in the GP + HIF-1α-siRNA group versus the GP + NC-siRNA group (Fig. 9m–o), suggesting that the upregulated expression of ADAM17 in GP-treated cardiomyocytes was largely induced by HIF-1α.

Discussion

In the present study, cardiomyocyte-specific ADAM17 knockout protected against left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in DCM of mice. The underlying mechanisms involved attenuated ACE2 shedding and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, increased AMPK phosphorylation, TFEB nuclear translocation and autophagosome formation as well as a normalized autophagic flux. As far as we are aware of, our study is the first report of the therapeutic effects and underlying mechanisms of ADAM17 deficiency on DCM.

ADAM17 mediates ectodomain shedding of a set of substrates and the main substrate of ADAM17 varies with different disease models33. We examined mRNA levels of 12 substrates of ADAM17 including TNF-α, TNF-αRI, TNF-αRII, IL-6, IL-6R, ALCAM, AREG, ERBB4, TGF-α, ICAM, VCAM, and ACE2 in a mouse model of DCM and found that only ACE2 mRNA level showed a significant change in the DCM mice than the control mice, suggesting that ACE2 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of DCM. Our results lent support to the notion that ACE2 is the main substrate of ADAM17 in the setting of DCM. Although the ACE2 mRNA level was markedly upregulated in diabetic mice likely due to a compensatory mechanism, the ACE2 protein level in the myocardium of diabetic mice did not increase in comparison to that in control mice. This uncoupling phenomenon between ACE2 mRNA and protein expression levels is supportive of the post-translational regulation of ACE2 due to the proteolytic shedding by ADAM17, whereas the deficiency of ADAM17 resulted in preserved ACE2 on the cardiomyocyte surface. These findings were consistent with a previous report showing contradictory results between mRNA and protein expression levels of ACE2 in ADAM17fl/fl mice receiving Ang II stimulation and suggesting a strong shedding effect of ADAM17 on ACE234. To evaluate whether the apoptotic response induced by ADAM17 was associated with ACE2 in cardiomyocytes, we measured the expression levels of Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase3 in ACE2-knockdown cardiomyocytes, and the results were opposite to that observed in ADAM17-knockdown cardiomyocytes. These findings demonstrated that ADAM17 was essential for cleaving ACE2, and ACE2 played a crucial role in the impact of ADAM17 on apoptotic response.

Previous studies reported that ACE2-knockout mice exhibited worsened cardiac function via inactivated myocardial AMPK35. AMPK is a key player in regulating a series of metabolic activities and AMPK activation has been confirmed to be beneficial for numerous metabolic diseases including DCM36. Recently, the research revealed that AMPK-mediated autophagic activation ameliorated oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic mice37. The AMPK and mTOR pathways are interlinked with often opposite functions in sensing the availability of nutrients and energy and regulation of cell growth38, and the AMPK/mTOR signaling has been recognized as a key regulator of autophagy26. The correlation between the mTOR and AMPK pathways was evidenced by the discovery of eukaryotic initiation factor 4EBP1 and p70S6K, which are downstream targets of mTOR26. As the crucial regulators of mRNA translation and protein synthesis, both p70S6K and 4EBP1 participate in cell growth, cell survival, and apoptosis39. Thus, the phosphorylation level and activity of p70S6K and 4EBP1 are commonly used as an indicator of activated mTOR signaling pathway26. In our study, the role of ADAM17 knockdown in AMPK/mTOR pathway and its downstream p-4EBP1 and p-p70S6K were examined in differentiated H9c2 cells, which showed that cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17 virtually reversed the inhibition of AMPK phosphorylation in DCM and ADAM17 played an important role in regulating AMPK/mTOR signal pathway.

As a new regulator of cell fate, the AMPK-TFEB pathway regulates the autophagic flux in the process of cell differentiation40. Upon stress, phosphorylated AMPK promotes TFEB transportation into the nucleus41, where TFEB binds promoters and controls numerous gene expression related to lysosomal functions such as phagocytosis, exocytosis, endocytosis, and autophagy25. A recent study showed that glucolipotoxicity diminished cardiomyocyte TFEB, which suppressed lysosomal autophagy and aggravated cardiac injury30. In a murine model of diabetes, cardiomyocyte autophagy was impaired42. Our results demonstrated that ADAM17 deficiency increased TFEB nuclear translocation both in vivo and in vitro, which reveals that ADAM17 might play a crucial role in the regulation of lysosome function.

As a scaffold protein containing multiple domains, P62 plays a critical role in regulating cell growth, cell survival, and inflammation43. In the process of lysosome degradation, p62 was degraded by proteolytic enzymes, and an elevated expression level of p62 has been deemed as an indicator of inhibited autophagy activity28,43. Beclin1 is a key regulator of autophagy and an inactive or dysfunctional Beclin1 leads suppressed autophagic process44. Thus, an abnormally low expression level of Beclin1 reflects a weakened autophagy44. Our results indicated that autophagic flux was suppressed in GP-treated cardiomyocytes and ADAM17 knockdown ameliorated autophagic flux.

Autophagy, as a cellular self-degradation process, maintains cellular integrity via eliminating damaged organelles and protein aggregates45. Current evidence indicates that activation of autophagy is a crucial cardioprotective mechanism that limits the accumulation of misfolded proteins46. As described previously, autophagy is a process including autophagy induction, cargo recognition, autophagosome formation, autophagosome-lysosome fusion, and substrate degradation29. One meaningful way to measure autophagy is to analyze the rate of autophagic flux rather than a snapshot look at autophagy at any one static point during the entire process29,47. CQ as a lysosomal acidification inhibitor to block fusion of autophagosome and lysosome, can cause autophagosome accumulation30. In this study, we administered CQ to clarify the specific process in autophagic flux ADAM17 may have impacts, and our results indicated that ADAM17 likely affected autophagosome formation in the early stage of autophagic flux.

LC3 which regarded as a marker of autophagosome in mammals, participates in the formation of autophagosome48 and the expression level of LC3 are proportional to the quantity of autophagic vacuoles49. Autophagy-related proteins participate in different steps of autophagy. Atg7, an E1-like enzyme, activates ubiquitin-like proteins Atg8 and Atg12 which undergo conjugation to form complexes that regulate the formation of autophagosome membranes50. It has been demonstrated that Atg5 and Atg7 were involved in the extension of autophagy membranes and formation of autophagic structures51, and Beclin-1, Atg3, Atg5, Atg7 and Atg12 participated in the process of autophagosome biogenesis52. In addition, the mRNA and protein expression of Atg5 and Atg7 were upregulated by inhibiting the mTOR pathway46. Our data demonstrated that expression of these autophagy-related proteins was downregulated in GP-treated cardiomyocytes, which was reversed by ADAM17 knockdown, suggesting that ADAM17 may play a significant role in the formation of autophagosomes.

Several questions regarding the pathological links in our animal experiments need to be addressed. First, why the expression and activity of ADAM17 were increased in diabetic mice? Previous studies showed that HIF-1α expression was increased in diabetic kidneys, which mediated the transcriptional upregulation of ADAM1732. Besides, the expression and activity of ADAM17 in macrophages were upregulated due to the activation of HIF-1α, leading to aggravated aortic dissection53. In our study, HIF-1α knockdown markedly attenuated the expression level of ADAM17, which was upregulated by GP treatment in NRCMs, suggesting that HIF-1α might act as an upstream mediator of upregulated ADAM17 in our diabetic mice. Second, how does ADAM17 affect AMPK phosphorylation? The results of RNA sequencing showed a significant difference in ADRA1A mRNA levels between A17α-MHCKO DM and A17fl/fl DM mice. It has been shown that ADRA1A directly regulated AMPK activation and thus, has been recognized as an upstream regulator of AMPK31. A previous study reported that activation of ADRA1A upregulated AMPK in skeletal muscle, resulting in an increased glucose uptake mediated by α1 adrenoceptor54. Our study revealed that ADRA1A protein level was markedly decreased in diabetic mice relative to control mice, which was reversed by cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of ADAM17. Similar results were derived from in vitro experiments in NRCMs. Thus, ADAM17 might affect AMPK signaling via ADRA1A. Third, how are autophagy and apoptosis logically related in diabetic mice? The casual relation between autophagy and apoptosis is highly controversial55 and depends on specific pathological background. Under some circumstances, such as in our mouse model of DCM, autophagy may constitute a stress adaptation against apoptosis and fibrosis, whereas in other conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction, autophagy may constitute an alternative cell-death pathway55. Autophagy, apoptosis and fibrosis can be caused by common diseases and signaling pathways, but in other instances, autophagy may affect apoptotic and fibrotic processes in a mutually exclusive manner55.

A major limitation of this study is a lack of preclinical studies using small molecule ADAM17 inhibitors in our mouse model or testifying our conclusions in human samples. Although some ADAM17 inhibitors have been screened for cancer research56, an ADAM17 inhibitor for attenuating DCM in mice has not been discovered. A major obstacle to a human sample study is due to the co-existence of extensive coronary atherosclerosis and DCM in almost all patients with advanced diabetes and it is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate the effect of ADAM17 on ischemic and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Further validation studies are required in this area.

In conclusion, an increased ADAM17 expression and activity and decreased ACE2 expression were identified in the diabetic hearts. Cardiomyocyte-specific ADAM17-knockout attenuated left ventricular fibrosis and cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ameliorated cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in DCM of mice. The mechanism may involve activated AMPK pathway, increased autophagosome formation and improved autophagic flux, which reduced the apoptotic response in cardiomyocytes. These findings may provide a novel and promising target for the prevention and treatment of DCM.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Wencheng Zhang, PhD, for his assistance with the preparation of this article. This work was supported by the International Collaboration and Exchange Program of China (81920108003), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (BP0719033), the State Key Program of National Natural Science of China (82030051), the grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170267, 82000411), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020QH023), Key Research and Development Plan of Shandong Province (2020ZLYS05, 2021SFGC0503, 2021ZDSYS05) and Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province of China (C.Z.).

Author contributions

F.X., J.C., Y.L., C.C., and M.Z. performed the in vivo and in vitro experiments, W.S. and W.C. analyzed the data and performed the statistical analysis, C.Z., Y.Z., and P.H. designed the study scheme and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the article.

Data availability

All the datasets presented in the paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Fei Xue, Jing Cheng

Contributor Information

Panpan Hao, Email: panda.how@sdu.edu.cn.

Yun Zhang, Email: zhangyun@sdu.edu.cn.

Cheng Zhang, Email: zhangc@sdu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41392-022-01054-3.

References

- 1.Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia. 2014;57:660–671. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isfort M, Stevens SC, Schaffer S, Jong CJ, Wold LE. Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail. Rev. 2014;19:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s10741-013-9377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022;79:1757–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonagh TA, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021;42:3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei CC, et al. Mast cell chymase limits the cardiac efficacy of Ang I-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:1229–1239. doi: 10.1172/JCI39345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh VP, Le B, Khode R, Baker KM, Kumar R. Intracellular angiotensin II production in diabetic rats is correlated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, oxidative stress, and cardiac fibrosis. Diabetes. 2008;57:3297–3306. doi: 10.2337/db08-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang F, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin 1-7: novel therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014;11:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos RAS, et al. The ACE2/angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas axis of the renin-angiotensin system: focus on angiotensin-(1-7) Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:505–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong B, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 overexpression improves left ventricular remodeling and function in a rat model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59:739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao P, et al. Combination of angiotensin-(1-7) with perindopril is better than single therapy in ameliorating diabetic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8794. doi: 10.1038/srep08794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zunke F, Rose-John S. The shedding protease ADAM17: physiology and pathophysiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017;1864:2059–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epelman S, et al. Soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in human heart failure: relation with myocardial function and clinical outcomes. J. Card. Fail. 2009;15:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, et al. Clinical relevance and role of neuronal AT(1) receptors in ADAM17-mediated ACE2 shedding in neurogenic hypertension. Circ. Res. 2017;121:43–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1999;99:3260–3265. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.25.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedak PW, et al. Altered expression of disintegrin metalloproteinases and their inhibitor in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113:238–245. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.571414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme is a key regulator of agonist-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2009;54:575–582. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan D, et al. A disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 regulates pressure overload-induced myocardial hypertrophy and dysfunction through proteolytic processing of integrin beta1. Hypertension. 2016;68:937–948. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan D, et al. Cardiomyocyte a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17) is essential in post-myocardial infarction repair by regulating angiogenesis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015;8:970–979. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.002029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh VP, Baker KM, Kumar R. Activation of the intracellular renin-angiotensin system in cardiac fibroblasts by high glucose: role in extracellular matrix production. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H1675–H1684. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91493.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel VB, et al. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 exacerbates diabetic cardiovascular complications and leads to systolic and vascular dysfunction: a critical role of the angiotensin II/AT1 receptor axis. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1322–1335. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branco AF, et al. Differentiation-dependent doxorubicin toxicity on H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012;12:326–340. doi: 10.1007/s12012-012-9177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branco AF, et al. Isoproterenol cytotoxicity is dependent on the differentiation state of the cardiomyoblast H9c2 cell line. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2011;11:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s12012-011-9111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, J. et al. AMPK: a balancer of the renin-angiotensin system. Biosci. Rep. 39, BSR20181994 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Settembre C, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SH, et al. Ezetimibe ameliorates steatohepatitis via AMP activated protein kinase-TFEB-mediated activation of autophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition. Autophagy. 2017;13:1767–1781. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1356977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Ji J, Yan XH. Cross-talk between AMPK and mTOR in regulating energy balance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012;52:373–381. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.500245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of lipid droplet protein PLIN2 triggers its degradation by CMA. Autophagy. 2016;12:432–438. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1124226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. p62 at the crossroads of autophagy, apoptosis, and cancer. Cell. 2009;137:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J. Pathol. 2010;221:117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trivedi PC, et al. Glucolipotoxicity diminishes cardiomyocyte TFEB and inhibits lysosomal autophagy during obesity and diabetes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1861:1893–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao W, Liu X. MiR-3682 promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) via inactivating AMPK signaling by targeting ADRA1A. Ann. Hepatol. 2022;27(Suppl 1):100570. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R, et al. High glucose up-regulates ADAM17 through HIF-1α in mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:21603–21614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.651604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arribas J, Esselens C. ADAM17 as a therapeutic target in multiple diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:2319–2335. doi: 10.2174/138161209788682398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel VB, et al. Angiotensin II induced proteolytic cleavage of myocardial ACE2 is mediated by TACE/ADAM-17: a positive feedback mechanism in the RAS. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014;66:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel VB, et al. ACE2 deficiency worsens epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65:85–95. doi: 10.2337/db15-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daskalopoulos EP, Dufeys C, Beauloye C, Bertrand L, Horman S. AMPK in cardiovascular diseases. Exp. Suppl. (2012) 2016;107:179–201. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-43589-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang F, et al. Exogenous H2S protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;43:1168–1187. doi: 10.1159/000481758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.González A, Hall MN, Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK and TOR: the Yin and Yang of cellular nutrient sensing and growth control. Cell Metab. 2020;31:472–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang X, Zhao Y. Effect of Orexin-A on cortisol secretion in H295R cells via p70S6K/4EBP1 signaling pathway. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015;2015:405157. doi: 10.1155/2015/405157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young NP, et al. AMPK governs lineage specification through Tfeb-dependent regulation of lysosomes. Genes Dev. 2016;30:535–552. doi: 10.1101/gad.274142.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H, et al. Metformin promotes the survival of random-pattern skin flaps by inducing autophagy via the AMPK-mTOR-TFEB signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019;15:325–340. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.29009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Unbreak my heart: targeting mitochondrial autophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;22:1527–1544. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manley S, Williams JA, Ding WX. Role of p62/SQSTM1 in liver physiology and pathogenesis. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2013;238:525–538. doi: 10.1177/1535370213489446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wirawan E, et al. Beclin1: a role in membrane dynamics and beyond. Autophagy. 2012;8:6–17. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.1.16645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariño G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song E, et al. Cardiac autophagy deficiency attenuates ANP production and disrupts myocardial-adipose cross talk, leading to increased fat accumulation and metabolic dysfunction. Diabetes. 2021;70:51–61. doi: 10.2337/db19-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition) Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JM, Huang S, Wu TT, Foster NR, Sinicrope FA. Prognostic impact of Beclin 1, p62/sequestosome 1 and LC3 protein expression in colon carcinomas from patients receiving 5-fluorouracil as adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2013;14:100–107. doi: 10.4161/cbt.22954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 conjugation system in mammalian autophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:2503–2518. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gozuacik D, Kimchi A. Autophagy as a cell death and tumor suppressor mechanism. Oncogene. 2004;23:2891–2906. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lian G, et al. Macrophage metabolic reprogramming aggravates aortic dissection through the HIF1α-ADAM17 pathway. EBioMedicine. 2019;49:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hutchinson DS, Bengtsson T. AMP-activated protein kinase activation by adrenoceptors in L6 skeletal muscle cells: mediation by alpha1-adrenoceptors causing glucose uptake. Diabetes. 2006;55:682–690. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rossello A, Nuti E, Ferrini S, Fabbi M. Targeting ADAM17 sheddase activity in cancer. Curr. Drug Targets. 2016;17:1908–1927. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160727143618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets presented in the paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.