Abstract

Chromatin is spatially organized into three-dimensional structures at different levels including A/B compartments, topologically associating domains and loops. The canonical CTCF-mediated loop extrusion model can explain the formation of loops. However, the organization mechanisms underlying long-range chromatin interactions such as interactions between A–A compartments are still poorly understood. Here we show that different from the canonical loop extrusion model, RYBP-mediated phase separation of CTCF organizes inter-A compartment interactions. Based on this model, we designed and verified an induced CTCF phase separation system in embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which facilitated inter-A compartment interactions, improved self-renewal of ESCs and inhibited their differentiation toward neural progenitor cells. These findings support a novel and non-canonical role of CTCF in organizing long-range chromatin interactions via phase separation.

Subject terms: Chromatin structure, Pluripotency

Introduction

Chromatin conformation capture techniques have shown that chromatin is spatially organized into three-dimensional (3D) structures at different levels including compartments (A or B), topologically associating domains (TADs) and loops.1–3 These structures affect gene expression, and are frequently disrupted in developmental disorders and cancer.4–6 The cohesin-dependent formation of loops can be explained by the loop extrusion model,3,7–10 wherein a cohesin ring slides along the DNA until it encounters CTCF proteins bound to convergently oriented CTCF motifs.3,11,12 Long-range chromatin interactions between compartments have also been observed to be associated with transcriptional control and cell fate transition.1 Transcriptionally active A compartments and transcriptionally silent B compartments interact with other A and B compartments, respectively.1 Cell differentiation is accompanied by global reorganization of chromatin structures and changes in long-range chromatin interactions between compartments.13 The extremely long-range promoter–promoter interactions are established during the ground-state to primed-state pluripotency transition.14 Nevertheless, the mechanisms underlying the organization of general long-range chromatin interactions are not well characterized.

We found that, in addition to organizing loops, CTCF is also able to organize long-range chromatin interactions between A compartments via phase separation behavior, and RYBP facilitates the phase separation of CTCF. Induced CTCF phase separation maintains embryonic stem cell (ESC) self-renewal, and inhibits their differentiation to neural progenitor cells (NPCs).

Results

CTCF organizes inter-A compartment interactions

To demonstrate whether CTCF regulates the organization of long-range chromatin interactions between compartments, we generated high-quality CTCF HiChIP data and obtained significant contacts (CTCF contacts), as exemplified by the enrichment of CTCF peaks at both CTCF HiChIP peaks and anchors of CTCF contacts (Supplementary information, Fig. S1a–c). Both CTCF ChIP-seq and CTCF HiChIP data revealed that CTCF preferentially participates in the A compartment interactions (Supplementary information, Fig. S1d), which was further confirmed by its high overlap efficiency with the open chromatin histone H3K27ac, and low overlap efficiency with H3K9me3 of B compartment (Supplementary information, Fig. S1e–g). Further analysis revealed that CTCF contributes to inter-A compartment interactions across the whole genome (Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary information, Fig. S1h). The high percentage of enriched CTCF peaks at the anchors of CTCF contacts between A compartments (CTCF inter-A anchors) confirmed these interactions (Supplementary information, Fig. S1i), which was also supported by CTCF ChIA-PET, CTCF PLAC-seq and Hi-C data4,15 (Fig. 1a; Supplementary information, Fig. S1j–l).

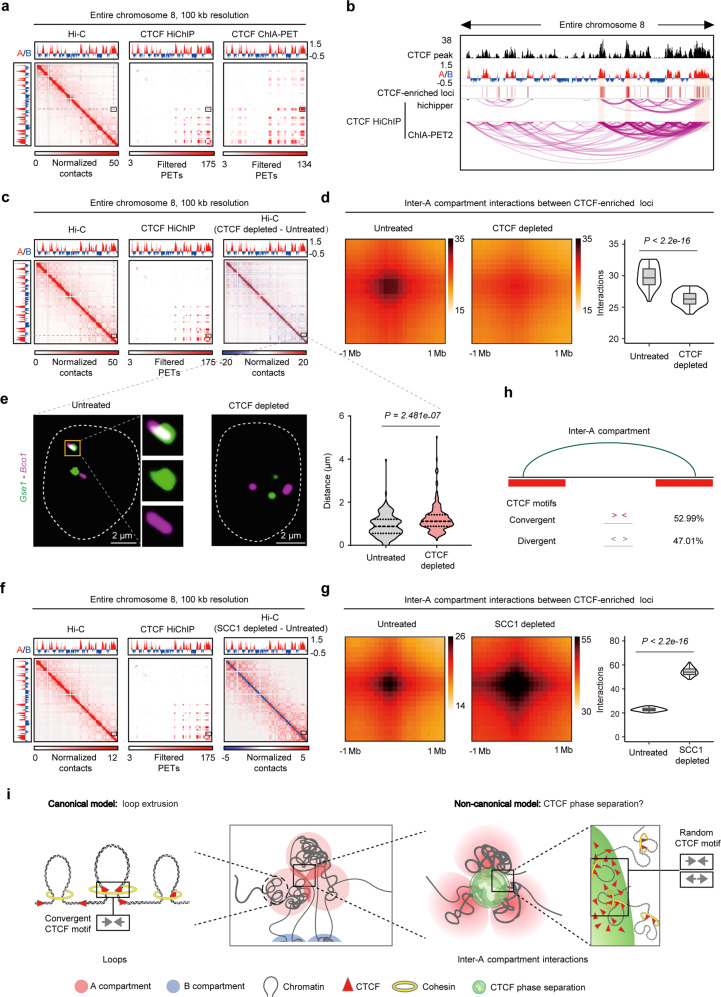

Fig. 1. CTCF organizes inter-A compartment interactions.

a In situ Hi-C contact heatmaps (left, GSE98671), CTCF HiChIP and CTCF ChIA-PET (right, GSM2645441) defined CTCF-connected regions (see Materials and Methods) across the entire chromosome 8. The black boxes denote inter-A compartment interactions. b CTCF HiChIP data showing inter-A compartment CTCF contacts at chromosome 8. c In situ Hi-C contact heatmaps (left), CTCF-connected regions and a subtracted Hi-C contact heatmap (right) across the entire chromosome 8. Hi-C data were from GEO: GSE98671.16 d Aggregate peak analysis (APA) plots (left) and quantitation (right) showing the genome-wide aggregate strength between CTCF-enriched loci (see Materials and Methods) from different A compartments after CTCF depletion, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Hi-C data from GEO: GSE9867116 were analyzed. e Representative images (left) and quantification (right) of DNA FISH displaying the distance change between Gse1 (green) and Bco1 (magenta) after CTCF depletion. The two genes locate at CTCF-enriched loci from different A compartments (box in c). Welch’s t-test; untreated: n = 194; CTCF depleted: n = 194. f Hi-C map at the entire chromosome 8 (left). CTCF-connected regions across the entire chromosome 8 (middle). Hi-C contact heatmap (SCC1 depleted – untreated) of the entire chromosome 8 (right). The accession number of SCC1 Hi-C data is E-MTAB-7816 (ArrayExpress). g APA plots (left) and quantitation (right) showing the genome-wide aggregate strength between CTCF-enriched loci from different A compartments after SCC1 depletion (Hi-C data), Wilcoxon rank-sum test. h Statistics of CTCF motif orientation at CTCF-enriched peaks between two different A compartments. i Distinct models of CTCF functions in organizing loops and interactions between A compartments. For loops, chromatin structures are organized via canonical loop extrusion model, which depends on cohesin and retention of CTCF at two convergent CTCF motifs (left). For long-range chromatin interactions, CTCF also organizes interactions between A compartments; this organization does not preferentially rely on cohesin and convergent CTCF motifs (right), and possibly occurs via CTCF phase separation.

To determine whether CTCF is required for the interactions between A compartments, we analyzed in situ Hi-C data from CTCF-depleted ESCs.16,17 A previous study reported that CTCF depletion reduces the strength of compartmentalization.16 We analyzed two sets of Hi-C data with different data processing methods,16,17 and found that CTCF depletion reproducibly decreased the interactions between a subset of A compartments (Supplementary information, Fig. S1m–p), specifically reduced the global interactions (to levels similar to that of SAFB-deficiency18) between A compartments that were connected by CTCF contacts (Fig. 1c; Supplementary information, Fig. S1q, r). We further revealed that CTCF depletion primarily reduced the interactions between CTCF-enriched loci from different A compartments (Fig. 1d; Supplementary information, Fig. S1s). The results from single-cell 3D-fluorescence in situ hybridization (3D-FISH) also showed that the paired genes in CTCF-enriched loci (Gse1 and Bco1, Uhrf1 and Msh6) from different A compartments interacted with each other, and the distance between them increased significantly upon CTCF depletion, while that between two unpaired genes was not significantly affected (Arhgap28 and Ubd) (Fig. 1e; Supplementary information, Fig. S1t, u). In global, CTCF HiChIP data revealed that CTCF contributes to the inter-A compartment interactions across 66.7% of the A compartments. These results indicate that CTCF organizes the interactions between A compartments through CTCF-enriched loci.

The formation of a subset of loops can be explained by the loop extrusion model,3,7–10 which depends on cohesin and CTCF retention at convergent motifs.8,19,20 To determine whether the inter-A interactions between CTCF-enriched loci still rely on loop extrusion, we analyzed the in situ Hi-C data after depleting the cohesin subunit, SCC1,21 and detected no global reduction in the interactions between CTCF-enriched loci from A compartments (Fig. 1f, g). Most CTCF loops always have convergent motif orientation.19,20 Regarding the interactive CTCF-enriched loci between A compartments, the proportion of convergent and divergent CTCF motifs were similar (Fig. 1h).

Taken together, CTCF organizes long-range chromatin interactions between A compartments through CTCF-enriched loci, likely through mechanisms inconsistent with the canonical loop extrusion model (Fig. 1i).

CTCF exhibits phase separation behavior in the nucleus

Recent studies show that long-range chromatin interactions tend to occur in nuclear bodies,22–25 of which many are the result of phase separation,26 raising the intriguing possibility that CTCF-mediated inter-A compartment interactions are regulated by phase separation (Fig. 1i). Nearly 51.5% of CTCF amino acid residues are intrinsically disordered (Fig. 2a), and CTCF exists as puncta in the nucleus (Fig. 2b). After photobleaching, the EGFP-tagged CTCF (CTCF-EGFP) puncta rapidly recovered fluorescence (Fig. 2c), which indicates their dynamic feature. The liquid-like properties of CTCF puncta were validated by their droplet fusion and fission behavior in vivo (Fig. 2d). In addition, 1,6-hexanediol (1,6-hex) treatment did not affect the survival of ESCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S2a), but reduced the number of large CTCF puncta, and did not significantly affect the number of small CTCF puncta (Fig. 2e). Results from fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) further revealed that large CTCF puncta rapidly recovered fluorescence within 1 min, while the smaller puncta were less efficient in recovering their fluorescence (Supplementary information, Fig. S2b, c). These results indicate that the large CTCF puncta are more dynamic than the small puncta. Therefore, the phase separation behavior of CTCF in the nucleus was observed.

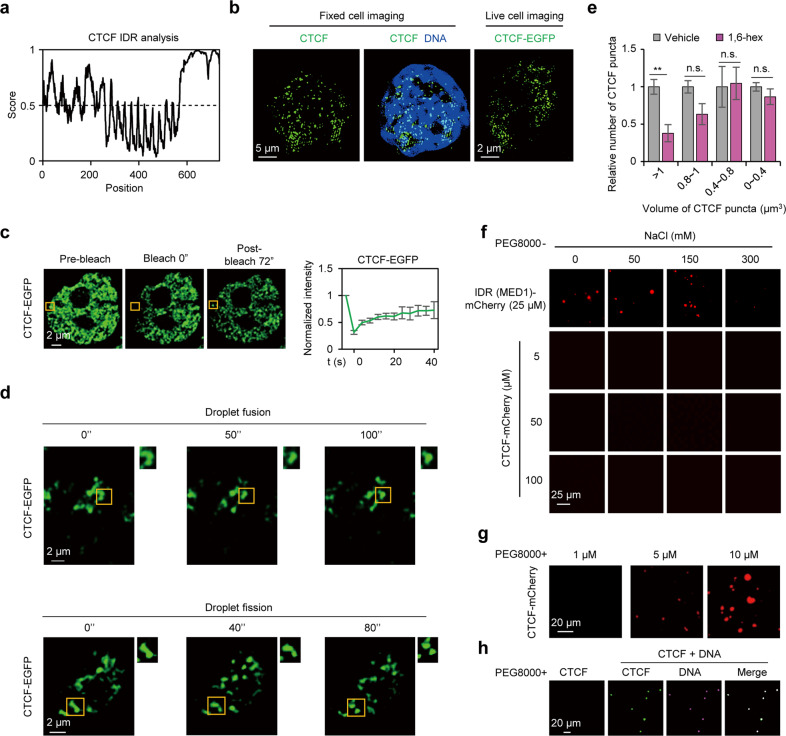

Fig. 2. CTCF exhibits phase separation behavior in the nucleus.

a Mouse CTCF is an intrinsically disordered protein predicted by IUPred2A;88 the score > 0.5 indicates IDR. b SIM microscopic images of CTCF immunofluorescence and live cell imaging in ESCs. Live imaging of ESCs expressing an EGFP-tagged CTCF.16 c Representative images (left) and quantification (right) of FRAP in ESCs expressing exogenous CTCF-EGFP. The yellow box highlights the bleached puncta. Data are plotted as means ± SEM, n = 3. d Droplet fusion and fission behavior of CTCF puncta in CTCF-EGFP ESCs. e Relative number of different volumes of CTCF puncta upon 1.5% 1,6-hex treatment. Welch’s t-test; vehicle, n = 60 cells; 1,6-hex, n = 82 cells. P values are (from left to right): P = 0.0045, P = 0.0632, P = 0.8989, P = 0.3059. f Representative images of droplet formation at different concentrations of NaCl and proteins. g Representative images of droplet formation at 1 µM, 5 µM and 10 µM CTCF in the presence of 20% PEG8000. h Representative images of CTCF-mCherry aggregation after addition of Cy5-labbled 25 × DNA motif. The concentration of CTCF-mCherry was 0.8 µM. n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01.

In vitro, we purified the mCherry-tagged full-length CTCF fusion protein (CTCF-mCherry) (Supplementary information, Fig. S2d), which did not form droplets under varying salt or protein concentrations (Fig. 2f; Supplementary information, Fig. S2e). As the positive control, 25 μM mCherry-tagged MED1 intrinsically disordered region (IDR (MED1)-mCherry) was sufficient to form droplets (Fig. 2f; Supplementary information, Fig. S2f). Since CTCF is a DNA-binding protein,27 we wondered whether DNA facilitates the phase separation of CTCF. CTCF prefers to accumulate at chromatin with specific DNA sequences,28 and previous work reported that DNA with 20 OCT4-binding sites efficiently facilitated droplet formation of OCT4 at very low concentration. The number of repeated motifs in a DNA sequence is positively correlated with its capacity to induce phase separation.29 Thus, we designed a DNA sequence with 25 CTCF-binding sites (25 × DNA motif) to verify its function on CTCF phase separation. The addition of 25 × DNA motif induced the formation of protein precipitates30 rather than round droplets of CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S2g). To further demonstrate the phase separation behavior of CTCF, the strong crowding agent, PEG8000, was added in the droplet formation buffer. The CTCF solution turned opaque, while no significant effect was observed with recombinant mCherry (Supplementary information, Fig. S2h). The formation of CTCF droplets in the presence of PEG8000 was dependent on the protein and salt concentration (Fig. 2g; Supplementary information, Fig. S2i–l). Addition of 25 × DNA motif significantly improved droplet formation of CTCF even with low concentrations in the presence of PEG8000 (Fig. 2h; Supplementary information, Fig. S2m). Furthermore, the CTCF droplets displayed droplet fusion behavior and 1,6-hex sensitivity (Supplementary information, Fig. S2n–p). After photobleaching in vitro, the CTCF droplets recovered their fluorescence (Supplementary information, Fig. S2q, r), although the recovery rate was slower than that observed in vivo (Supplementary information, Fig. S2s). Altogether, CTCF exhibits phase separation behavior in the nucleus, but more rigorous conditions are needed for in vitro phase separation of CTCF, it is possible that additional factors facilitate the phase separation behavior of CTCF in vivo.

RYBP facilitates CTCF to undergo phase separation

To screen factors that facilitate CTCF phase separation, we performed IDR analysis of proteins known to interact with CTCF, or protein components of biomolecular condensates that co-localize with CTCF31 (Supplementary information, Table S1). The abundance of IDR indicates potential of protein aggregation.32,33 RING1 and YY1-binding protein (RYBP), a self-associated protein which acts as a component of the Polycomb group for transcriptional repression,34,35 exhibits the highest percentage (88.2%) of intrinsically disordered amino acid residues among all candidate proteins (Fig. 3a, b), and physically interacts with CTCF in ESCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S3a, b). In addition, RYBP is preferentially enriched at A compartments like CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S3c), and displays obvious co-binding with CTCF at chromatin (Supplementary information, Fig. S3d). Therefore, we speculated that RYBP facilitates the phase separation of CTCF.

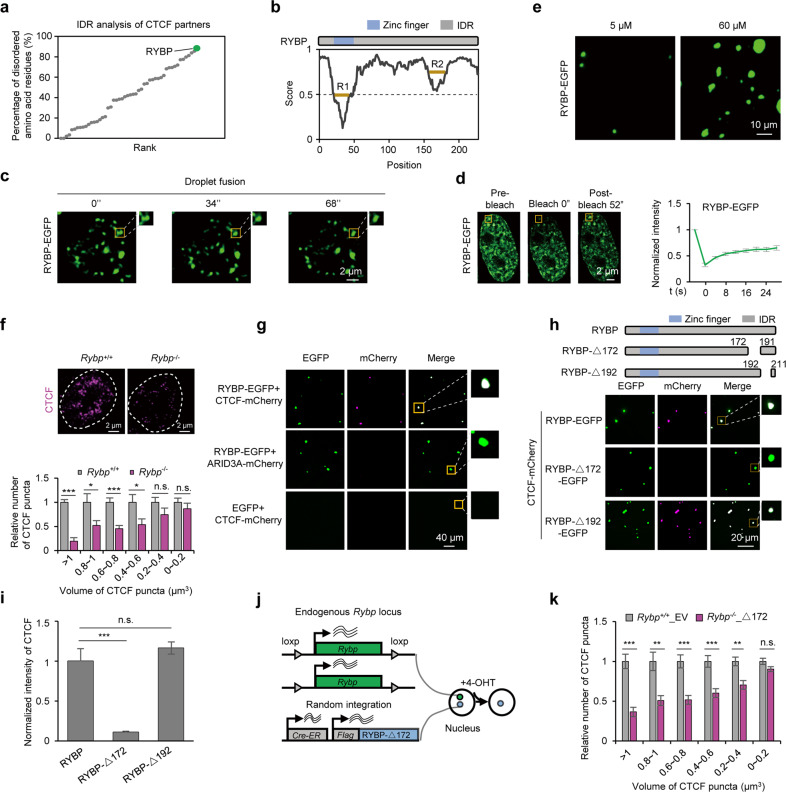

Fig. 3. RYBP facilitates CTCF to undergo phase separation.

a IDR analysis of CTCF partners, the involved interaction partners of CTCF were extracted from the BIOGRID database. Polycomb group components were also analyzed, since Polycomb body is reported to co-localize with CTCF.31 b RYBP is an intrinsically disordered protein predicted by IUPred2A.88 R1 and R2 denote the relatively low disordered regions of RYBP. c Droplet fusion behavior of RYBP puncta in an EGFP-tagged RYBP-expressing ESC (RYBP-EGFP ESC). d Representative FRAP images (left) and quantification (right) in ESCs expressing exogenous RYBP-EGFP, n = 3. The yellow box denotes the bleached puncta. e Representative images showing droplet formation of 5 µM and 60 µM RYBP-EGFP recombinant protein. f Representative immunofluorescence images (top) and statistics (bottom) of CTCF puncta before and after RYBP depletion. Welch’s t-test; Rybp+/+, n = 61 cells; Rybp–/–, n = 37 cells. P values are (from left to right): P = 7.47e–06, P = 0.0465, P = 0.0008, P = 0.0466, P = 0.1662, P = 0.3842. g RYBP droplets incorporate CTCF protein in vitro without PEG8000. The concentration of RYBP-EGFP and EGFP was 60 µM; the concentration of CTCF-mCherry and ARID3A-mCherry was 10 µM. h Top: experimental pipeline for the mutational strategy of RYBP. Bottom: full-length or mutant RYBP droplets incorporate CTCF protein without PEG8000 in vitro. The concentration of RYBP-EGFP, RYBP-Δ172-EGFP and RYBP-Δ192-EGFP was 60 µM; the concentration of CTCF-mCherry and mCherry was 10 µM. i Normalized intensity of CTCF in full-length or mutant RYBP droplets. Welch’s t-test; RYBP, n = 25; RYBP-Δ172, n = 35; RYBP-Δ192, n = 23. P values are (from left to right): P = 9.028e–06, P = 0.064. j Experimental pipeline for the construction of RYBP mutant cell line. k Relative number of different volumes of CTCF puncta in Rybp+/+_EV or Rybp–/–_Δ172 cell lines. Welch’s t-test; Rybp+/+_EV, n = 85 cells; Rybp–/–_Δ172, n = 164 cells. P values are (from left to right): P = 6.59e–05, P = 0.0032, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0007, P = 0.0015, P = 0.0736. n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To test the hypothesis stated above, we first analyzed the phase separation ability of RYBP. Live cell imaging revealed that RYBP existed as puncta, exhibited droplet fusion behavior and dynamic properties after FRAP (Fig. 3c, d; Supplementary information, Videos S1 and S2). In vitro, the recombinant RYBP protein formed round droplets in physiological NaCl buffer in a protein and salt concentration-dependent manner, which were sensitive to 1,6-hex and displayed droplet fusion feature (Fig. 3e; Supplementary information, Fig. S3e–i). The IDR of RYBP is sufficient to form dynamic droplets (Supplementary information, Fig. S3j–m). In addition, we predicted the potential amino acid residues that might contribute to RYBP phase separation based on our previously reported algorithm,36,37 and identified 21 high-confidence amino acid residues at RYBP IDR (Supplementary information, Fig. S3n). The deletion of these residues (RYBP-ΔIDR21) prevented the formation of round droplets in vitro, and instead resulted in protein precipitates lacking dynamics (Supplementary information, Fig. S3o–q). As a control, RYBP with zinc finger depletion (RYBP-Δ26) still formed droplets (Supplementary information, Fig. S3o). These results indicated that RYBP is capable of undergoing phase separation.

Given that RYBP significantly co-localized with CTCF puncta in the nucleus (Supplementary information, Fig. S4a, b), we next investigated whether phase separation of RYBP facilitates CTCF aggregation. To this end, we generated RYBP knockout (Rybp–/–) ESCs by treating the Rybp-floxed (Rybp+/+) ESCs with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) for 2 days (Supplementary information, Fig. S4c). Depletion of RYBP did not affect the expression of CTCF, but significantly decreased the number of large CTCF puncta (Fig. 3f; Supplementary information, Fig. S4c). In contrast, RYBP overexpression had the opposite effect (Supplementary information, Fig. S4d). Furthermore, recombinant RYBP induced droplet formation by CTCF in vitro even when the latter was present at a low concentration of 10 µM (Fig. 3g), which is in contrast to the failure of CTCF to form droplets even at high concentration (100 µM) (Fig. 2f). As two negative controls, the recombinant EGFP did not induce CTCF aggregation, and RYBP had no droplet formation-promoting effect on other DNA-binding proteins such as ARID3A (Fig. 3g). In the sedimentation assay38 as well, very low amount of CTCF was detected in the pellets after addition of EGFP, while RYBP was able to aggregate 53.2% of the CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S4e, f). In contrast, CTCF only slightly improved the aggregation of RYBP (Supplementary information, Fig. S4e, g), which suggests that CTCF might be a passenger of RYBP phase separation.39 To further verify that phase separation of RYBP induces CTCF aggregation, we exogenously expressed full-length RYBP (RYBP-RFP), RYBP-ΔIDR21 (RYBP-ΔIDR21-RFP) and HNRNPA1 IDR-fused RYBP-ΔIDR21 (RYBP-ΔIDR21-HNRNPA1c-RFP) in endogenous RYBP-depleted ESCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S4h), and achieved similar expression levels of the three proteins in the respective cell lines (Supplementary information, Fig. S4i). RYBP-ΔIDR21 is difficult to form puncta in the nucleus (Supplementary information, Fig. S4j, k), and significantly reduced the number of large CTCF puncta (Supplementary information, Fig. S4l). C-terminal IDR of HNRNPA1 (HNRNPA1c) is known to drive phase separation;40,41 Therefore, fusing RYBP-ΔIDR21 with a non-murine native HNRNPA1c (RYBP-ΔIDR21-HNRNPA1c-RFP) rescued its defective aggregation, and also restored the number of large CTCF puncta in endogenous RYBP-depleted ESCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S4j–l). These results demonstrated that phase separation of RYBP aggregates CTCF.

We next analyzed the amino acid residues of RYBP that facilitate CTCF aggregation. The low disordered segments at both the non-disordered and disordered regions might contain peptide motif that promotes specific protein–protein interactions.42 Based on our previously reported algorithm,36,37 we further predicted the 172–191 amino acid (aa) sequence at the low disordered region of RYBP (R2 of Fig. 3b) as the candidate due to its lowest phase variance value, which indicates its involvement in phase separation (Supplementary information, Fig. S5a). Compared to the full-length RYBP, the mutant protein with 172–191 aa deletion (RYBP-Δ172) was ineffective in facilitating CTCF aggregation, and also displayed impaired interaction with CTCF. In contrast, deletion of 192–211 aa (RYBP-Δ192), a sequence with high phase variance value, did not significantly affect CTCF aggregation (Fig. 3h, i; Supplementary information, Figs. S4e and S5b, c). We therefore established the Rybp–/–_Δ172 cell line with endogenous RYBP deletion and ectopic RYBP-Δ172 expression (to the level similar to that of endogenous RYBP) (Fig. 3j; Supplementary information, Fig. S5d–f). The number of large CTCF puncta in Rybp–/–_Δ172 cells was significantly reduced compared to that in Rybp+/+ ESCs expressing the empty vector (Rybp+/+_EV) (Fig. 3k). We also predicted the potential amino acid residues at CTCF likely involved in the interaction with RYBP using Raptorx,43 and generated CTCF recombinant protein lacking these residues (Supplementary information, Fig. S5g). These mutations did not affect the aggregation of CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S5h), but the CTCF mutant no longer underwent aggregation in RYBP droplets (Supplementary information, Figs. S4e and S5g, i, j). Taken together, we identified the specific amino acid residues in RYBP and CTCF that are required for the co-phase separation between RYBP and CTCF.

The internal region in the RNA-binding region (RBRi) of CTCF promotes its self-clustering in vivo.44 Presence of RNA strands significantly facilitated the droplet formation of full-length CTCF, but not of the RBRi-deleted mutant (ΔRBRi-CTCF) (Supplementary information, Fig. S5k, l). RNA also significantly increased the size of RYBP–CTCF co-phase separated droplets by 1.5-fold, which was decreased following RBRi deletion (Supplementary information, Fig. S5m, n). Therefore, RNA facilitates CTCF phase separation via RBRi, and also facilitates RYBP-mediated CTCF droplet formation partly via the RBRi of CTCF.

Collectively, these results indicate that RYBP is able to undergo phase separation, and in turn facilitates the phase separation of CTCF.

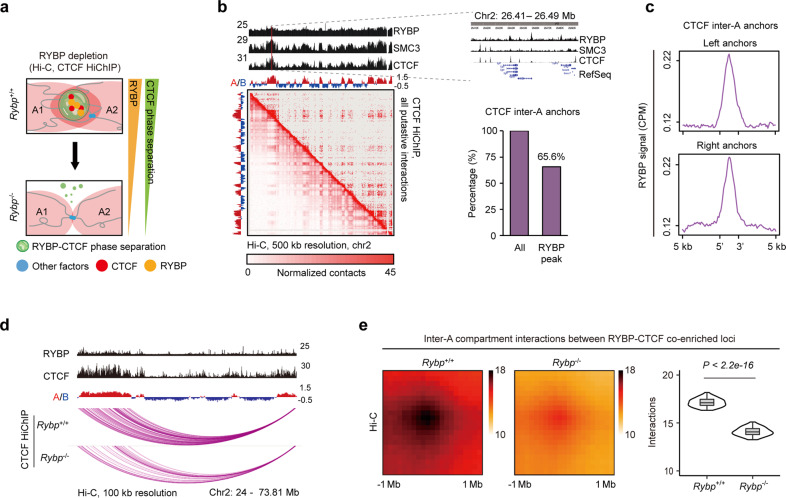

RYBP depletion attenuates the CTCF-mediated interactions between A compartments

The RYBP-facilitated CTCF phase separation led us to consider whether RYBP is also required for the CTCF-mediated inter-A compartment interactions. To this end, both Hi-C and CTCF HiChIP were performed in RYBP-depleted ESCs (Fig. 4a). Depletion of RYBP did not alter the expression of key factors associated with ESC fate decision, including OCT4, SOX2, NANOG and SSEA1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S6a), indicating that the pluripotent state of ESCs was unaffected. In addition, the absence of RYBP also had little effect on genome partitioning into A and B compartments (Supplementary information, Fig. S6b). RYBP was globally enriched at CTCF inter-A anchors (Fig. 4b, c), thus the RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (see Materials and Methods) were defined to investigate the relationship between RYBP and CTCF in chromatin organization. CTCF HiChIP data revealed that RYBP depletion significantly impaired the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (Fig. 4d; Supplementary information, Fig. S6c). Hi-C data further revealed that RYBP or CTCF depletion both reduced the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP-CTCF co-enriched loci (Fig. 4e; Supplementary information, Fig. S6d), and the inter-A compartment interactions impaired upon CTCF depletion were also globally reduced after RYBP depletion (Supplementary information, Fig. S6e). We also found that RYBP peaks significantly overlapped with CTCF peaks in the chromatin (Supplementary information, Fig. S6f), and RYBP loss reduced the genome-wide enrichment of CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S6g, h), which may explain the above observations. However, since RYBP is a multifunction protein,34 majority of CTCF-independent RYBP peaks or CTCF-independent chromatin organization functions of RYBP were also observed (Supplementary information, Fig. S6f).

Fig. 4. RYBP depletion attenuates CTCF-mediated inter-A compartment interactions.

a Schematic diagram showing the experimental detection of the interaction alteration between A compartments after RYBP depletion using Hi-C and CTCF HiChIP. A1 and A2 denote different A compartments. b The RYBP, SMC1 and CTCF ChIP peaks across chromosome 2 (top). Hi-C and CTCF HiChIP contact heatmaps at 500-kb resolution across the entire chromosome 2 (bottom left). Percentage of CTCF inter-A anchors with RYBP peak (bottom right). c RYBP ChIP-seq signal at CTCF inter-A anchors. d A representative region of two A compartments showing the putative interactions before or after RYBP depletion (CTCF HiChIP). e APA plots (left) and quantitation (right) showing the genome-wide aggregate strength between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci from different A compartments after RYBP depletion (Hi-C data), Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

To summarize, RYBP depletion impaired the CTCF-mediated interactions between A compartments, especially reduced the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci.

Induced CTCF phase separation restores inter-A compartment interactions impaired by RYBP depletion

Given that RYBP facilitates both CTCF phase separation and CTCF-mediated inter-A compartment interactions, we next analyzed whether RYBP regulates inter-A compartment interactions through phase separation of CTCF. To this end, we first determined the role of CTCF phase separation on inter-A compartment interactions. DNA was aggregated in CTCF droplets, which were augmented by further addition of full-length RYBP, but not RYBP-Δ172 in vitro (Supplementary information, Fig. S7a, b). Disrupting CTCF aggregation in vivo by 1,6-hex treatment, RYBP depletion or RYBP mutation (RYBP-Δ172) reduced the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (Fig. 4e; Supplementary information, Fig. S7c–e).

Next, we explored whether restoring CTCF phase separation recovered the impaired interactions between A compartments (Fig. 5a). CTCF phase separation was restored in RYBP-depleted cells by exogenously expressing a fusion protein of CTCF with HNRNPA1 IDR (hIDR-CTCF) (Fig. 5a; Supplementary information, Fig. S7f). In contrast to CTCF alone, the purified hIDR-CTCF fusion protein formed abundant droplets in vitro (Fig. 5b; Supplementary information, Fig. S7g). Compared to the Rybp–/– ESCs expressing the empty vector (Rybp–/–_EV), exogenous expression of hIDR-CTCF in Rybp–/– ESCs (Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF) significantly improved the formation of CTCF puncta (Fig. 5c; Supplementary information, Fig. S7h). RYBP depletion significantly decreased the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (Fig. 4e); these interactions were globally increased after inducing CTCF phase separation and involved 37.8% (401/1061) of A compartments (Fig. 5d–f; Supplementary information, Fig. S7i, j). When we further disrupted the phase separation in Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF cells by 1,6-hex treatment, the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci reduced again (Supplementary information, Fig. S7k). Single-cell DNA FISH coupled with immunofluorescence revealed that paired genes in RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci from different A compartments co-localized at CTCF or RYBP puncta (Fig. 5g; Supplementary information, Fig. S7l–o). The distance between these paired genes increased upon RYBP depletion, and decreased after inducing CTCF phase separation (Fig. 5g, h; Supplementary information, Fig. S7n, o). As a negative control, RYBP depletion or inducing CTCF phase separation did not significantly affect the distance between two unpaired genes (Fig. 5i, j)

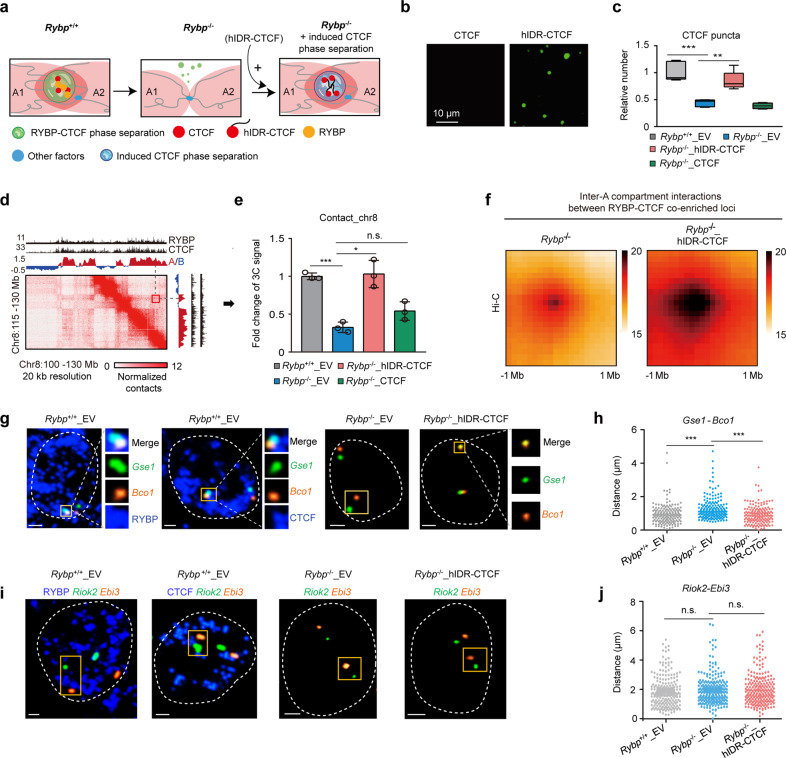

Fig. 5. Induced CTCF phase separation restores inter-A compartment interactions impaired by RYBP depletion.

a Experimental schematic; A1 and A2 denote different A compartments. b Droplet formation of recombinant CTCF and hIDR-CTCF proteins without PEG8000; the protein concentration was 10 µM. c Boxplot showing the relative number of highly concentrated CTCF puncta in different groups. Rybp+/+_EV denotes the empty vector-expressing Rybp+/+ ESCs; Rybp–/–_EV denotes the empty vector-expressing Rybp–/– ESCs; Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF denotes the hIDR-CTCF-expressing Rybp–/– ESCs; Rybp–/–_CTCF denotes the WT CTCF-expressing Rybp–/– ESCs. Welch’s t-test; n values are (from left to right): n = 65 cells, n = 133 cells, n = 93 cells. n = 150 cells. P values at top are (from left to right): P = 0.0001551, P = 0.003076. d A representative region of Hi-C contact maps; red fragment showing the contacts between the two A compartments. e 3C-qPCR showing the interaction alteration between two RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci from different A compartments (red box in d). Welch’s t-test; n = 3. P values at top are (from left to right): P = 0.0004, P = 0.0124, P = 0.0723. f APA plots showing the genome-wide aggregate strength between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci from different A compartments after inducing CTCF phase separation (Hi-C data). g DNA FISH coupled with RYBP or CTCF immunofluorescence displaying the distance change between Gse1 (green) and Bco1 (yellow) in different cell lines. The two genes are localized in RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci. All the scale bars denote 2 μm. h The distance change between Gse1 and Bco1 in different cell lines. Welch’s t-test; Rybp+/+_EV: n = 167; Rybp–/–_EV: n = 154; Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF: n = 175. P values are (from left to right): P = 5.12e–07, P = 5.782e–08; Welch’s t-test. i DNA FISH coupled with RYBP or CTCF immunofluorescence displaying the distance change of Riok2 (green) and Ebi3 (yellow) in different cell lines which is used as a negative control. All the scale bars denote 2 μm. j The distance change between Ebi3 and Riok2 in different cell lines. Welch’s t-test; n values are (from left to right): n = 158, n = 179, n = 194. P values are (from left to right): P = 0.3864, P = 0.4016; Welch’s t-test. qPCR data show means ± SD. n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Collectively, we successfully established a method for inducing CTCF phase separation, which restored the decreased interactions between A compartments through RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci in RYBP-depleted ESCs, thereby supporting a model that CTCF organizes inter-A compartment interactions via phase separation.

Induced CTCF phase separation improves self-renewal of ESCs

CTCF prefers to accumulate at transcriptionally active loci across different cell lines (Supplementary information, Fig. S8a). However, CTCF is selectively enriched at the promoters of pluripotency-associated genes in ESCs as opposed to the differentiated cells such as cortical neuron (CN) cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S8b). CTCF co-localizes with RYBP at the transcription activated loci (Supplementary information, Fig. S8c, d),45–47 and RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks occur at TAD boundaries that are usually enriched with highly transcribed genes (Supplementary information, Fig. S8e, f).2,48 These results suggested that RYBP-mediated CTCF phase separation possibly contributes to the transcriptional activation of genes in ESCs.

To demonstrate this hypothesis, disrupting CTCF phase separation via RYBP deficiency reduced the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters (Fig. 6a; Supplementary information, Fig. S9a), and reduced the expression of most genes close to these RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks (Fig. 6b, c; Supplementary information, Fig. S9b). Induced CTCF phase separation in RYBP-depleted cells restored the interactions between these paired genes such as Cdt1 and Mcm5 (Fig. 6d, e; Supplementary information, Fig. S9c, d), and also up-regulated the expression of most genes close to RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks (Fig. 6e, f; Supplementary information, Fig. S9e). When we further disrupted the phase separation in Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF cells by 1,6-hex treatment, the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters reduced again (Supplementary information, Fig. S9f). Therefore, phase separation behavior of CTCF regulates inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters, and is involved in transcriptional activation.

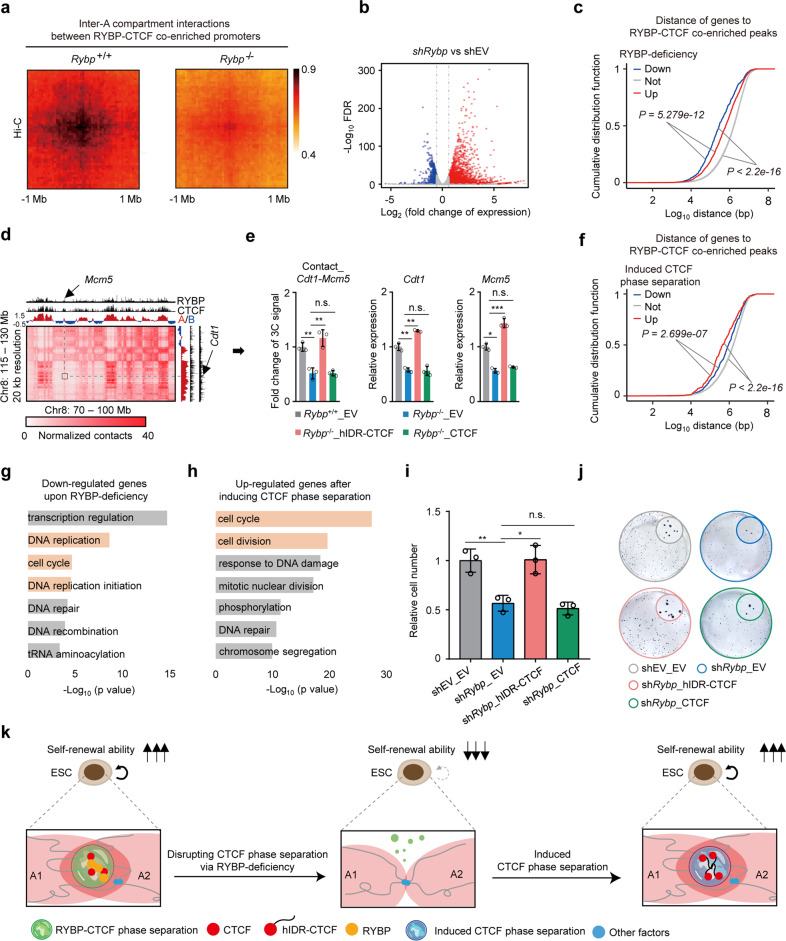

Fig. 6. Induced CTCF phase separation improves self-renewal of ESCs.

a APA plots showing the genome-wide aggregate strength between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters (see Materials and Methods) from different A compartments after RYBP depletion (Hi-C data). b Volcano plot showing the expression change of genes in A compartments after Rybp knockdown for 96 h. c Cumulative distribution showing the distance of gene promoters to their closest RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks (see Materials and Methods) between A compartments after RYBP knockdown. ‘Up’, ‘Down’ and ‘Not’ represent that those genes were up-regulated, down-regulated and unchanged after Rybp knockdown, respectively; K-S test. d Representative region of Hi-C contact maps at the inter-compartment level with 20-kb resolution. Black box shows the interacted region between the two A compartments. e 3C-qPCR showing the interaction alteration between two genes from different A compartments (left). RT-qPCR (middle and right) showing the relative expression of these genes. The genomic positions analyzed by 3C-qPCR locate in RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci. Welch’s t-test; P values are (from left to right): P = 0.0072, P = 0.0088, P = 0.9553, P = 0.0024, P = 0.0012, P = 0.8045, P = 0.0186, P = 2.033e–05, P = 0.5408; n = 3. f Cumulative distribution showing the distance of gene promoters to their closest RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks between A compartments after inducing CTCF phase separation (Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF vs Rybp–/–_EV); K-S test. g Gene ontology analysis showing the biological processes of genes that are down-regulated after Rybp knockdown. h Gene ontology analysis showing the biological processes of genes that are up-regulated after inducing CTCF phase separation in RYBP-depleted ESCs. i Relative cell number in different groups (see Materials and Methods); Welch’s t-test; n = 3; P values are (from left to right): P = 0.008904, P = 0.01705, P = 0.4265. j Colony formation assay (CFA) of ESCs in different groups. k A model showing the role of CTCF phase separation in self-renewal of ESCs. A1 and A2 denote different A compartments. n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. qPCR data show means ± SD.

The genes down-regulated after disruption of CTCF phase separation and those up-regulated after its induction were enriched in multiple biological processes, such as transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, tRNA aminoacylation and chromosome segregation. The affected cell cycle-associated terms raised the possibility that induced CTCF phase separation facilitates self-renewal of ESCs (Fig. 6g, h). Compared to the empty vector control (shEV_EV) group, RYBP-deficient ESCs (shRybp_EV) showed significantly lower proliferation ability (Fig. 6i) and formed fewer colonies (Fig. 6j; Supplementary information, Fig. S9g), whereas induction of CTCF phase separation in RYBP-deficient cells restored their self-renewal ability (Fig. 6i, j; Supplementary information, Fig. S9g). We also induced CTCF phase separation via exogenously expressing RYBP IDR- and FUS IDR-fused CTCF in RYBP-deficient ESCs (RYBP–/–_IDR2-CTCF and RYBP–/–_IDR3-CTCF, respectively) (Supplementary information, Fig. S9h, i), which rescued their proliferation and colony formation capacities (Supplementary information, Fig. S9j, k). In contrast, compared to the Rybp+/+_EV ESCs, the Rybp–/–_Δ172 cells with disrupted CTCF phase separation showed impaired inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters, and reduced gene expression and self-renewal capacity (Supplementary information, Fig. S9l–o).

Taken together, inducing CTCF phase separation improved self-renewal of ESCs (Fig. 6k).

Induced CTCF phase separation inhibits ESC differentiation toward NPCs

Since RYBP represses the expression of genes involved in neuronal development (Supplementary information, Fig. S10a), we also determined whether phase separation of CTCF regulates the differentiation of ESCs. The differentiation of ESCs to NPCs was accompanied by RYBP down-regulation and a significant decrease in the number of CTCF puncta (Fig. 7a, b; Supplementary information, Fig. S10b, c), while the expression levels of CTCF did not reduce (Supplementary information, Fig. S10c), indicating that the observed reduction in CTCF phase separation was not due to reduced expression of CTCF. Induction of CTCF phase separation during ESC differentiation through ectopic expression of hIDR-CTCF (Fig. 7c, d) maintained ESC pluripotency even after 6 days of exposure to differentiation stimuli, as indicated by the colony morphology and the expression of alkaline phosphatase (AP), OCT4 and NANOG (Fig. 7e, f). Concurrently, exogenous expression of hIDR-CTCF significantly inhibited the expression of NPC lineage genes (Fig. 7f, g). However, ESC-derived cells with ectopic CTCF or empty vector expression completely differentiated into fibroblast-like cells lacking AP, OCT4 and NANOG, and expressing high levels of NPC lineage genes (Fig. 7e–g). We also induced CTCF phase separation via exogenously expressing two additional types of IDR-fused CTCF (IDR2-CTCF and IDR3-CTCF) or full-length RYBP, which also significantly inhibited the expression of NPC lineage genes (Supplementary information, Fig. S10d–g). Thus, induced CTCF phase separation inhibits the differentiation of ESCs to NPCs.

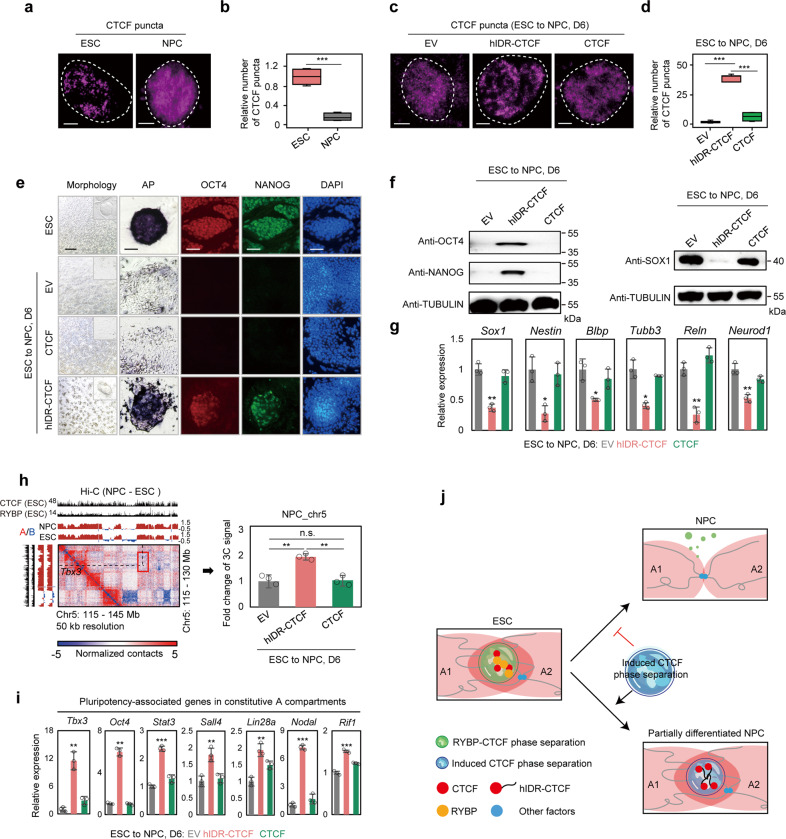

Fig. 7. Induced CTCF phase separation inhibits ESC differentiation toward NPCs.

a Representative immunofluorescence images of CTCF puncta in ESCs and NPCs. Scale bar denotes 2 μm in each image. b Boxplot showing the relative number of highly concentrated CTCF puncta in ESCs and NPCs. Welch’s t-test; ESCs: n = 71 cells; NPCs: n = 169 cells; P = 7.271e–06. c Representative immunofluorescence images of CTCF puncta in ESC-derived cells, which were differentiated from ESCs to NPCs for 6 days. Prior to differentiation, ESCs stably expressed exogenous empty vector (EV), hIDR-CTCF, and CTCF, respectively. Scale bar denotes 2 μm in each image. d Boxplot showing the relative number of highly concentrated CTCF puncta in ESC-derived cells, which were differentiated from ESCs stably expressing EV, hIDR-CTCF and CTCF to NPCs for 6 days, respectively. Welch’s t-test; EV: n = 384 cells; hIDR-CTCF: n = 331 cells; CTCF: n = 327 cells. P values are (from left to right): P = 7.592e–09, P = 2.334e–05. Scale bar denotes 2 μm in each image. e Morphology, AP staining, immunofluorescence of ESCs and ESC-derived cells, which were differentiated from ESCs stably expressing EV, hIDR-CTCF and CTCF to NPCs for 6 days, respectively. The scale bar at ‘morphology’ row denotes 500 μm, the scale bars at rest rows denote 50 μm. f Western blot showing the expression of different proteins in ESC-derived cells, which were differentiated from ESCs stably expressing EV, hIDR-CTCF and CTCF to NPCs for 6 days, respectively. g Relative mRNA expression of NPC-associated genes in ESC-derived cells, which were differentiated from ESCs stably expressing EV, hIDR-CTCF and CTCF to NPCs for 6 days, respectively. Welch’s t-test. The difference between EV and hIDR-CTCF groups are (from left to right): P = 0.0013; P = 0.0109; P = 0.0365; P = 0.0147; P = 0.0016; P = 0.0031, n = 3. h A representative region of subtracted (NPC – ESC) Hi-C contact map at chromosome 5 (left). 3C-qPCR showing the interaction alteration between two RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci from different constitutive A compartments (red box in left contact map) among ESC-derived cells (right). Welch’s t-test. P values are (from left to right): P = 0.0055, P = 0.4139, P = 0.002; n = 3. i Relative mRNA expression of pluripotency genes in ESC-derived cells. P values are (from left to right): P = 0.0082, P = 0.0017, P = 9.983e–05, P = 0.0071, P = 0.0034, P = 7.25e–06, P = 5.546e–05; n = 3; Welch’s t-test. j Schematic diagram showing the role of CTCF phase separation-mediated inter-A compartment interactions in ESC differentiation. During the differentiation of ESCs to NPCs, CTCF phase separation and inter-A compartment interactions decrease. Induced CTCF phase separation restores the inter-A compartment interactions, inhibits cell fate transition from ESCs to NPCs, and finally produces partially differentiated NPCs. A1 and A2 denote different A compartments. qPCR data show means ± SD. n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To demonstrate the alteration of inter-compartment interaction during differentiation, we defined constitutive A compartments as A compartments in both ESCs and NPCs to exclude a possible effect of compartment A/B switching on chromatin structure (Supplementary information, Fig. S10h). The constitutive A compartments were also enriched with CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S10i). Consistent with the previous work,13 during ESC differentiation into NPCs, the global interactions between constitutive A compartments decreased (Supplementary information, Fig. S10j), and we also observed decreased inter-constitutive A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (Supplementary information, Fig. S10k). The down-regulated genes were closer to RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks when compared to up-regulated or unaltered genes (Supplementary information, Fig. S10l). The down-regulated genes were enriched in multiple functional terms including immune system process, cell adhesion, transcriptional regulation and stem cell population maintenance (Supplementary information, Fig. S10m). Induced CTCF phase separation is able to increase the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci during ESC differentiation (Fig. 7h). Since induced CTCF phase separation maintained the pluripotency of ESC during differentiation, the expression levels of ESC pluripotency-associated genes (Supplementary information, Fig. S10n) also increased in constitutive A compartments after inducing CTCF phase separation (Fig. 7f, i). Therefore, the differentiation of ESCs to NPCs was accompanied by decreased inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci.

RYBP is required for the phase separation of CTCF (Fig. 3). The expression levels of both RYBP and CTCF in ESCs were higher than that in most differentiated cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S10o), which suggested that CTCF phase separation is seemingly abundant in ESCs, and decreased in differentiated cells. These results further supported the role of CTCF phase separation in the maintenance of pluripotency.

RYBP was initially identified as a component of non-canonical PRC1,35,49 which is required for repressing the expression of developmental genes.35,50 Thus, we explored whether the functions of RYBP in CTCF phase separation are still restricted in non-canonical PRC1. 85.2% of the RYBP-CTCF co-localized puncta lacked RING1B in the nucleus (Supplementary information, Fig. S11a, b). ChIP-seq data revealed that majority of RYBP–CTCF co-binding peaks showed low enrichment of RING1B, H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3, and the abundance of transcriptional activation-associated modified histones including H3K27ac and H3K4me3 (Supplementary information, Figs. S8d, S11c). These peak-targeted genes are enriched in self-renewal associated terms (Supplementary information, Fig. S11d), which is consistent with the effects of RYBP-mediated CTCF phase separation in the self-renewal of ESCs (Fig. 6k). These functions of RYBP in CTCF regulation are different from the traditional function of RYBP in non-canonical PRC1 that inhibits the expression of developmental genes.35,50 Regarding gene expression, we defined the RYBP_PRC1-related genes as the significantly changed genes in both RYBP- and RING1B-deficient ESCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S11e). The CTCF phase separation-related genes were defined as those from two gene clusters, one consisting of genes that were down-regulated upon RYBP-deficiency and up-regulated after induction of CTCF phase separation, and the second comprising genes that were up-regulated upon RYBP-deficiency and down-regulated after induction of CTCF phase separation (Supplementary information, Fig. S11f). 79.5% of the CTCF phase separation-related genes did not overlap with RYBP_PRC1-related genes (Supplementary information, Fig. S11g). YAF2, a paralog of RYBP, is also a hallmark of non-canonical PRC1,51,52 and no obvious physical interaction between CTCF and YAF2 was observed (Supplementary information, Fig. S11h). As a positive control, the interaction between CTCF and SMC1 was observed (Supplementary information, Fig. S11h). Deficiency of YAF2 neither significantly changed the expression of CTCF (Supplementary information, Fig. S11i, j), nor reduced the number of CTCF puncta (Supplementary information, Fig. S11k). Consistently, the depletion of RING1B did not affect the expression of CTCF and RYBP or the number of RYBP–CTCF co-localized puncta (Supplementary information, Fig. S11l–n). During the differentiation of ESCs to NPCs, the expression levels of both YAF2 mRNA and protein were increased (Supplementary information, Fig. S11o) in contrast to the reduction in RYBP levels (Supplementary information, Fig. S10b, c). Therefore, functions of RYBP in CTCF phase separation are primarily different from that in non-canonical PRC1.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that CTCF phase separation safeguards ESC maintenance, and that induced CTCF phase separation inhibits the differentiation of ESCs to NPCs (Fig. 7j).

Discussion

Chromatin is spatially organized into 3D chromatin structures such as loops, the formation of which is explained by the loop extrusion model.3,7–10 We found that CTCF is able to organize long-range chromatin interactions between A compartments via phase separation. Previous studies have reported that disruption of local insulation does not affect higher-order chromosome folding, but they also reported a subset of reproducible reduction in the strength of compartmentalization upon CTCF depletion.16 We further demonstrated that the inter-A compartment interactions between CTCF-enriched loci were impaired after CTCF depletion. A previous study showed that the distance between DXZ4 and X130 loci (> 15.8 Mb) increased after CTCF deficiency,53 which supports our finding that CTCF regulates the extremely long-range chromatin interactions. Compartments span across a wide region of chromatin,1 RYBP–CTCF phase separation does not mediate all the contacts between A compartments. Other factors, such as SRRM2 or SAFB, might also contribute to partial inter-A compartment interactions.18,54 As a multifunction protein,34 RYBP might also be able to organize chromatin structures in a CTCF phase separation-independent manner. In addition, we also did not exclude the possibility that CTCF could organize inter-A compartment interactions independent of phase separation. Therefore, multiple mechanisms might exist for the organization of inter-A compartment interactions.

Several studies have been conducted on nuclear condensates including CTCF clusters,44,55 and we further demonstrated the RYBP-dependent phase separation of CTCF. RYBP is a component of non-canonical PRC1 and required for the formation of Polycomb body.35,49,50,56 However, RYBP-mediated CTCF puncta are primarily distinct from Polycomb body. Although CTCF is a ubiquitously expressed protein,4 CTCF puncta were abundant in ESCs, and decreased or even disappeared in differentiated cells despite the high expression of both CTCF and RYBP. In addition, the distinct dynamics of in vitro and in vivo CTCF phase separation might be explained by the different components in droplets, which may also explain the greater dynamics of large CTCF puncta than that of small puncta. In the present study, RYBP was identified as a key factor that improved CTCF dynamics in ESCs. In other cells with low expression level of RYBP, CTCF puncta might lack phase separation dynamics or maintain its dynamics through other factors.

We found that cohesin was primarily enriched at the RYBP–CTCF co-binding loci and incorporated into RYBP–CTCF co-localized puncta (Supplementary information, Fig. S12a, b). Depletion of cohesin did not reduce the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci (Supplementary information, Fig. S12c),8,57–61 but eliminated the Hi-C loops which are anchored at RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci within A compartments (Supplementary information, Fig. S12d). Thus, cohesin may mediate loop extrusion at RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci within compartments.

Pluripotency-associated genes or Hox cluster genes usually assemble into larger clusters via long-range chromatin interactions.50,62,63 These gene clusters are either transcriptionally active or silent depending on their recruitment to nuclear condensates.50,63–65 Gene co-expression is the potential functional consequence of phase separation-mediated long-range chromatin interactions.65,66 Manipulating CTCF phase separation affect the expression of many genes, which are not specifically restricted in pluripotency-associated genes. In ESCs, multiple genes, including pluripotency- or self-renewal-associated genes interact with other genes from different A compartments via RYBP–CTCF phase separation-mediated long-range chromatin interactions. Pol II exhibits phase separation behavior in the nucleus and is a close partner of CTCF.19,67 Therefore, Pol II might also be incorporated into the RYBP–CTCF phase separation, and regulate the co-expression of the associated genes. We found that RYBP-mediated CTCF phase separation is abundant in the ESCs. The altered gene expression during differentiation could be the result of the loss of interaction between CTCF and RYBP, which triggers the differentiation of ESCs. Inducing CTCF phase separation maintains the pluripotency of ESCs through the high expression level of pluripotency-associated genes. Since loop extrusion competes with compartmental phase separation,8,57 another possible mechanism for the anti-differentiation effect of induced CTCF phase separation might be that CTCF promotes enhancer–promoter looping of differentiation genes,27 and that induced CTCF phase separation competes with CTCF from loop extrusion to maintain the expression of pluripotency-associated genes.

Our findings provide an efficient strategy for regulating pluripotency of ESCs via manipulating phase separation. IDR of mouse RYBP-fused CTCF is insufficient to demonstrate the effects of induced CTCF phase separation, since additional effects beyond phase separation of RYBP IDR might exist. In the present study, a non-native human HNRNPA1 that shows low homology with mouse HNRNPA1 was fused with the protein of interest in mouse ESCs (mESCs). HNRNPA1 IDR from the same species is not recommended in order to minimize the potential effects of HNRNPA1 IDR beyond inducing phase separation. Therefore, multiple different IDRs are recommended to be used for driving phase separation.

In summary, our study demonstrated a non-canonical role of CTCF in organizing long-range chromatin interactions between active chromatin compartments via RYBP-mediated phase separation formation. Our findings provide new insights into the relationships among phase separation, 3D chromatin structures, and pluripotency regulation, as well as a method of regulating pluripotency by manipulating phase separation.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

Wild-type male mouse ESCs were derived from a mixed (129 × 1 × 129S1) mouse, and cultured in gelatin-coated dish with ESC medium, which consists of DMEM (Hyclone), 15% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Thermo Fisher), 1% (v/v) nucleoside mix (Sigma), 1000 U/mL recombinant LIF (Millipore).

Mouse Rybp-floxed ESCs (Rybp+/+) ESCs were a gift from the Vidal lab.68 Cells were cultured on inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Mouse Rybp+/+ ESCs were cultured in ESC medium with 0.5 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, Sigma) for 2 days to obtain RYBP knockout (Rybp–/–) ESCs.

Mouse CTCF-EGFP-AID ESCs were a gift from Bruneau lab,16 and were cultured in gelatin-coated dish with ESC medium. For CTCF depletion, the cells were cultured in ESC medium with 0.5 mM IAA for 2 days.

To establish the Rybp–/–_Δ172 cell line, whose expression level of exogenous RYBP-Δ172 was similar to that of endogenous RYBP in Rybp+/+_EV cell line, we first established an Rybp–/–_FLAGRYBP cell line. This cell line was prepared from Rybp+/+ ESCs that exogenously expressed a FLAG-tagged RYBP (exoRYBP), whose endogenous RYBP was depleted via 4-OHT treatment (Rybp–/–_FLAGRYBP). Then we picked a cell clone, whose expression level of exogenous RYBP in Rybp–/–_FLAGRYBP was similar to endogenous RYBP (endoRYBP) in Rybp+/+_EV cell line (expressed an empty vector in Rybp+/+ ESCs) identified by anti-RYBP antibody. Rybp–/–_FLAGRYBP cell line was used to quantify the following mutant RYBP cell line, whose expression level of exogenous mutant RYBP is similar to the endogenous RYBP in Rybp+/+_EV cell line identified by anti-FLAG antibody. The detailed information of all plasmids in the present work was provided in Supplementary information, Table S2.

Induced CTCF phase separation

Three different IDR-fused CTCF constructs, including C-terminal IDR of human HNRNPA1 (186–320 aa)-fused CTCF (hIDR-CTCF), C-terminal IDR of mouse RYBP (51–228 aa)-fused CTCF (IDR2-CTCF), N-terminal IDR of human FUS (1–214 aa)-fused CTCF (IDR3-CTCF), were transfected to ESCs, respectively. Stable cell lines were obtained after drug selection.

Induced differentiation of ESCs toward NPCs

To induce differentiation toward NPCs, mESCs were cultured in N2B27 medium with DMEM/F12, Neurobasal, N2 and B27 for 2 days, then retinoic acid (Sigma) was added into N2B27 medium for additional 4 days. For verifying the role of CTCF phase separation in NPC development, Rybp+/+ ESCs exogenously expressing empty vector, hIDR-CTCF, IDR2-CTCF, IDR3-CTCF, full-length RYBP and CTCF were induced for NPC differentiation. mESCs expressing pTripz-RYBP were induced for NPC differentiation with (NPC_Rybp OE group) or without addition (NPC_ vehicle group) of doxycycline (Dox).

Immunofluorescence and live cell imaging

For immunofluorescence analysis, mESCs were grown on gelatin-coated glass for 24 h. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min. After washes for three times, cells were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100. Following washes in PBS, cells were blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. Then cells were incubated with primary antibodies in 3% BSA overnight at 2–8 °C. After washes in PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h. For live cell imaging, cells were cultured at eight-well dish for 24 h. The fixed cells and live cells were imaged using N-SIM or confocal microscopy.

FRAP

mESCs stably expressing RYBP-EGFP or CTCF-EGFP were cultured in gelatin-coated eight-well dishes for 24 h. FRAP was performed using a Nikon Eclipse Ti with 488 nm laser. The fluorescence intensity of the bleached cell at each time point was normalized by the fluorescence intensity of the background region and the fluorescence intensity of an adjacent unbleached cell. The images were analyzed using NIS-Elements software.

Immunodepletion and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Immunodepletion and co-IP were performed based on a previously published protocol.69,70 For immunodepletion, nuclear extracts from about 6 × 107 mESCs were sequential immunoprecipitated with 3 μg of anti-RYBP antibody conjugated with Protein G agarose beads (Roche Diagnostics). Each IP was performed at 4 °C for 6 h. After washing for three times, the beads were eluted by boiling with 80 μL elution buffer (E1, E2 and E3 from each round of elution), then the suspension (S1, S2 and S3 after each round of IP) was transferred for the next round of IP. For Co-IP, nuclear extracts from mESCs were inculcated with 4 μg anti-CTCF antibody-coated protein G-Agarose (Roche). IgG (Millipore) was used as a negative control, and the nuclear extracts were used as a positive control.

Protein expression and purification

The cDNA was cloned into a modified version of a T7 pET expression vector. The base vector was engineered to include His-tag followed by EGFP or mCherry. For protein expression, plasmids were transformed into BL21 cells (Transgene Biotech). A fresh bacterial colony was inoculated into LB medium containing kanamycin and grown overnight at 37 °C. Bacterial cultures were diluted in 500 mL LB with kanamycin, and were grown for approximately 5 h at 37 °C until the OD600 value reached 0.6. Then IPTG was added into the culture media for inducing the expression of proteins at 16 °C. Protein purification was performed according to the instruction of Protein Purification Kit (Cwbio).

In vitro droplet assay

Recombinant EGFP or mCherry fusion proteins were concentrated and desalted to an appropriate protein concentration in 125 mM NaCl using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Genebrick). Recombinant proteins were added into solutions at varying concentrations of NaCl in droplet formation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT) with or without PEG8000 as the statement in the figures or figure legends. The concentration of each protein was also described in the figures or figure legends. The protein solution was immediately loaded onto slides, which were imaged with microscope (Nikon).

Regarding the DNA-facilitated CTCF aggregation, 5 ng/μL 25 × DNA motif was added into the droplet formation buffer with or without PEG8000. The sequence of CTCF motif was calculated by Homer software, the detailed sequence of DNA with 25 CTCF-binding sites (underline highlighted) and spacer was showed as the follows:

tgtaaaacgacgcggtcaggatcctaggcttaatagtgccctctggtggccatgcagtacatagtgccctctggtggccagcatgaatatagtgccctctggtggccataagcttgatagtgccctctggtggccagtttcagaatagtgccctctggtggccacggctagcatagtgccctctggtggccagggctagaatagtgccctctggtggccagccggataatagtgccctctggtggccaggcgattcatagtgccctctggtggccagccaaatcatagtgccctctggtggccagcatgaacatagtgccctctggtggccaggcttacaatagtgccctctggtggccagaaacataatagtgccctctggtggccacgatcgaaatagtgccctctggtggccagtagccgaatagtgccctctggtggccagtagctaaatagtgccctctggtggccagaaatcggatagtgccctctggtggccagtagcaatatagtgccctctggtggccactagcctaatagtgccctctggtggccaaccctagcatagtgccctctggtggccaggatcctaggcttaatagtgccctctggtggccatgcagtacatagtgccctctggtggccagcatgaatatagtgccctctggtggccataagcttgatagtgccctctggtggccagtttcagaatagtgccctctggtggccatagattcggcggccgcgtcatagctgtttcctg

1,6-hex treatment

For cell imaging or Hi-C experiment in vivo, mESCs were grown on glass plate and incubated with 1.5% 1,6-hex in culture media for 2 min. For testing the sensitivity of droplets to 1,6-hex in vitro, the droplets were treated with 10% 1,6-hex for 30 min.

Immunofluorescence coupled with FISH

Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 12 min, washed in PBS for twice. After removing background with 1 mg/mL NaBH4, cells were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, followed by incubating at 37 °C in 100 μg/mL RNaseA for 45 min to remove RNA. Cells were treated with 50% formamide in 2× SSCT at 4 °C overnight to loosen the chromatin, followed by heating at 78 °C for 10 min, and incubated in 70%, 85% and 100% ethanol for 1 min, respectively. Probes in hybridized buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 1% Triton X-100 in 2× SSC) were added into dish and incubated with cells at 37 °C for 20 h. After washing with 2× SSC for 6 times, the cells were incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS for 6 times, cells were imaged with z-stack of microscope. The distance between two genes were calculated with NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

In situ Hi-C

In situ Hi-C was performed according to a previously published protocol.7 In brief, five million cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. DNA was digested with MboI, and the ends of restriction fragments were labeled using biotinylated nucleotides. After reversal of crosslinks, ligated DNA was purified and sheared to a length of 300–500 bp. After purification, DNA was prepared for sequencing. Each group was prepared with two replicates.

HiChIP

HiChIP was performed based on a reported work.71 Rybp+/+ mESCs were cultured on inactivated MEFs with methanol or 4-OHT for 2 days. After detaching cells from plates, cells were cultured in dishes for 1 h. Non-adherent cells were transferred to a new dish for another 1-h culture to remove MEF cells completely. 15 million Rybp+/+ mESCs cultured in methanol or 4-OHT (Sigma) containing medium were crosslinked and digested with MboI restriction enzyme. Nucleotides containing biotin-dATP were used to fill in the restriction fragment overhangs. After sonication, 11.25 μg anti-CTCF (Abclonal) antibody was incubated with the samples overnight. Then DNA was captured with protein A beads. After elution, DNA was pulled down with streptavidin T1 beads. The purified DNA was mixed with indexes for sequencing using TruePrepTM Index Kit V2 for Illumina® (Vazyme). Each group was prepared with two replicates.

ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR

ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR were performed based on the ChIP-seq method with slight modification.72 After formaldehyde crosslinking and sonication, each sample was incubated with 10 μg antibody-coated beads (Thermo Fisher). Purified DNA was dissolved in H2O and subjected to sequencing or quantitative real-time PCR. The PCR primers were available in Supplementary information, Table S3.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq was performed according to a previous description.70 For the RNA-seq of RYBP-deficiency, lentivirus containing shRNA targeting Rybp mRNA (shRybp) or empty vector (shEV) were prepared. Then mESCs were infected with shRybp or shEV lentivirus for 96 h; 2 μg/mL puromycin was added into the culture medium for drug selection of infected cells. For RNA-seq of cells with induced CTCF phase separation, empty vector-expressing Rybp+/+ mESCs (Rybp+/+_EV) and hIDR-CTCF-expressing Rybp+/+ (Rybp+/+_hIDR-CTCF) mESCs were cultured on inactivated MEFs with 4-OHT for 4 days to obtain Rybp–/–_EV and Rybp–/–_hIDR-CTCF, respectively. After removing MEF cells completely, the total mRNA was extracted for sequencing. Each group was prepared with two replicates.

3C coupled with qPCR (3C-qPCR)

3C was performed as previously described.7 Briefly, 1 × 107 cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and then quenched with glycine. After washing three times in PBS, cells were suspended in 250 µL Hi-C lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 0.2% IGEPAL and protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C to isolate the nuclei. After washing once in Hi-C lysis buffer, nuclei were suspended in 50 µL 0.5% SDS for 8 min at 62 °C, then the SDS was quenched with 145 µL H2O and 25 µL 10% Triton X-100 for 15 min at 37 °C. Chromatin was digested with MboI (NEB) overnight at 37 °C, then the digested fragments were incubated with 1.5 µL 10 mM dNTP, 8 µL DNA polymerase I (NEB) and 40.5 µL H2O for 1.5 h at 37 °C. The samples were then incubated with 663 µL H2O, 120 µL NEB T4 ligase buffer, 100 µL 10% Triton-X 100, 12 µL 10 mg/mL BSA, and 5 µL T4 DNA ligase for 4 h at room temperature. After reversal of crosslinks with proteinase K, the DNA was purified and diluted to 100 ng/µL for PCR. Primers used are listed in Supplementary information, Table S4. The interaction frequency was normalized to B2M.73

Quantitative Real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent, and cDNA was prepared from RNA using a reverse transcriptase kit (Takara). The level of Gapdh was used as a normalization control. The primer sequences were listed in Supplementary information, Table S5.

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted using CytoBuster (Merck), and chromatin proteins were extracted using the ChromaFlash Chromatin Extraction Kit (Epigentek). Proteins were run on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and were wet-transferred to 0.45-μm PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After three times of washes, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with Femto ECL substrate and imaged using a CCD camera.

Colony formation assay (CFA) and proliferation assay

ESCs were prepared with following groups: (1) mESCs transfected with piggyBac-empty vector plasmids and shRNA lentivirus containing empty vector (shEV_EV), (2) mESCs transfected with piggyBac-empty vector plasmids and shRNA lentivirus targeting Rybp (shRybp_EV), (3) mESCs transfected with piggyBac-hIDR-CTCF plasmids and shRNA lentivirus targeting Rybp (shRybp_hIDR-CTCF), (4) mESCs transfected with piggyBac-CTCF plasmids and shRNA lentivirus targeting Rybp (shRybp_CTCF). The same number of cells in each group were seeded in dishes with three replicates and cultured for 5 days. AP staining was performed to detect newly formed colonies. For the proliferation assay, ESCs in each group were plated at the same cell number with three replicates. The cell number was calculated after 5 days.

Rybp+/+_EV mESCs and mutant RYBP (RYBP-Δ172)-expressing Rybp+/+ mESCs were planted in gelatin-coated dishes, and cultured in medium with methanol (for Rybp+/+_EV) or 4-OHT (for RYBP-Δ172-expressing Rybp+/+ mESCs) for 5 days, followed by CFA and proliferation assay.

Prediction of key amino acid residues for phase separation

We predicted the key amino acid residues for RYBP phase separation based on our previously reported algorithm of PSPHunter (https://github.com/jsun9003/PSPHunter).36,37 Key amino acid residues of RYBP for phase separation were predicted using the strategy with each three consecutive amino acids as a unit. The key regions that might be required for co-phase separation between RYBP and CTCF were predicted using the strategy with each 20 consecutive amino acids as a unit. The physically interacted amino acid residues of CTCF with RYBP were predicted by Raptorx (http://raptorx.uchicago.edu/ComplexContact).

Puncta analysis

To quantify the puncta in cells, fixed immunofluorescence cells were imaged by confocal microscopy using the same parameters across different treatment groups. Cells were captured with the z-stack model. Using imaris software (Bitplane), the number and volume of puncta in cells were calculated.

Definition of promoters

Gene promoters were defined as follows. First, the gene list of mm9 was downloaded using the R package GenomicFeatures (version 1.38.1). Next, promoters of mm9 were defined as ± 3 kb from the transcription start site of genes using the R package BSgenome (version 1.54.0).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Fastq files were extracted from SRA using Sratoolkit (version 2.8.1), quality-checked by FastQC (version 0.11.8) and aligned onto mm9 reference genome using Bowtie2 (version 2.2.5) with default parameters.74 Reads with a mapq score less than 30 were filtered out by using Samtools (version 1.9).75 Duplicates were discarded from mapped reads with Picard MarkDuplicates (version 1.118). Peaks were called with MACS276 (version 2.1.2, with parameters: --nomodel --extsize 147).

RNA-seq data analysis

Fastq data were quality-checked by FastQC (version 0.11.8). Paird-end reads were aligned using STAR77 (version 2.6.1b, default parameters), and mm9 was used as reference genome. Gene-specific read counts were calculated using FeatureCounts78 (version 1.6.0, parameters: ‘-p’). Differentially expressed genes were detected with R package EdgeR79 (version 3.16.5). FDR < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5 or < –1.5 were used as thresholds.

Hi-C data analysis

Adapters were trimmed with Cutadapt (version 2.4). Next, the Hi-C paired-end reads were aligned to the mm9 reference genome. Invalid pairs and PCR duplications were filtered out using HiC-Pro80 (version 2.11.1, parameters: default settings). Intra-chromosomal valid pairs were used to generate contact matrices. To generate Hi-C contact matrices, all Hi-C valid pairs were transferred to ‘.hic’ format files using command of juicer (v1.11.04),81 Hi-C raw and VC-normalized contact matrices at 100 kb, 50 kb, 20 kb resolution were then extracted using dump command of juicer (v1.11.04).81 For each chromosome, the VC-normalized 100-kb, 50-kb and 20-kb resolution contact matrices were used to call A/B compartments and define TADs and loops.

For compartmentalization analysis, the first principal component (PC1) values were calculated from VC-normalized contact matrices at 100-kb resolution separately for each chromosome using eigenvector cooltools v0.3.2. Next, each bin was classified into A or B compartments according to its PC1 value. Eigenvalues with higher gene density were defined as A compartment, otherwise as B compartment.

During the ESC differentiation to NPCs, we defined constitutive A compartment as regions that are A compartment in both ESCs and NPCs, and constitutive B compartment as regions that are B compartment in both ESCs and NPCs. The compartment, which is A compartment in ESCs, and turn to be B compartment in NPCs, was defined as A to B compartment. The compartment, which is B compartment in ESCs, and turn to be A compartment in NPCs, was defined as B to A compartment. The percentage was calculated in ESCs.

To analyze contact changes at the compartment level, the number of valid pairs in each chromosome were downsampled to match the chromosome with the lowest number of valid pairs. The VC-normalized contact matrices at 100-kb resolution were extracted. Constitutive compartments were defined as regions with same eigenvalues in each sample. The VC-normalized contacts within or between each constitutive compartment were added up as intra-compartment contacts and inter-compartment contacts.

For TAD analysis, the 50-kb VC-normalized contact matrices were used to calculate insulation index as per a previous method82 (parameters: ‘-is 1000000 -ids 600000 -im mean -bmoe 0 -nt 0.1 -v’). Gaps between two boundaries with length more than 100 kb were defined as TADs.

Saddle plots were performed using GENOVA to test the inter-compartment interaction changes under different conditions. VC-normalized Hi-C contact matrices at 100-kb resolution were generated; matrices were sorted by the PC1 score of compartments.

Aggregated peak analysis (APA) was performed using GENOVA to test the enrichment of CTCF putative inter-A compartment interactions (see below). VC-normalized Hi-C contact matrices at 100-kb resolution were generated as described above. Submatrices around RYBP–CTCF co-enrich loci were extracted from each VC-normalized matrix and then added up. interactions surrounding the center (< 300 kb) were quantified.

To define CTCF-enriched loci, we first split the entire genome into 100-kb bins. Next, we calculated the CTCF enrich score (signal of CTCF ChIP-seq data divides signal of ChIP-seq input data) for each 100-kb bin. The 10% 100-kb bins with top 10% CTCF enrich score were defined as CTCF-enriched loci, while the 10% 100-kb bins with the lowest 10% CTCF enrich score were defined as CTCF-lack loci.

To define RYBP-CTCF co-enriched loci, we used CTCF and RYBP ChIP-seq data to call the enrich score for each 100-kb bin respectively according to the above method. These 100-kb bins with both top 20% RYBP and CTCF enrich score were defined as RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci.

RYBP–CTCF co-enriched peaks were defined as RYBP–CTCF co-binding peaks within RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci. When the two ChIP-seq peaks which have at least 1 bp overlapped with each other were defined as RYBP–CTCF co-binding peaks.

To define the RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters, we split these RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci into 20–kb bins. The 20–kb bins containing RYBP–CTCF co-binding promoters were defined as RYBP–CTCF co-enriched promoters.

The highly dynamic inter-A compartment interactions were defined as the inter-A compartment interactions between RYBP–CTCF co-enriched loci, whose normalized contacts highly decreased (fold change < 0.8) after RYBP depletion and were restored (fold change > 1.2) upon inducing CTCF phase separation.

CTCF peaks in loci of inter-A compartment interactions were used to analysis the motif orientations of CTCF.

A quality control of Hi-C data was provided in Supplementary information, Table S6.

HiChIP data analysis

Adapters were first trimmed with Cutadapt (version 2.4). Next, the adapter-trimmed paired-end reads were aligned to mm9 with HiC-Pro80 (version 2.11.1). HiChIP peaks and significant interactions were called using Hichipper83 (version 0.7.7) with parameters ‘-min-dist 1000 -max-dist 100000000 -read-length 150’. All replicates were merged together and all read pairs were used to call peaks. Contacts with P ≤ 0.01 and read pairs ≥ 2 were defined as CTCF contacts. The HiChIP peak related contacts were named as putative interactions.

To detect the differences of HiChIP data between two conditions, the putative interactions in each sample were downsampled to match the sample with the lowest number of interactions. All putative interactions were assigned to A–A, B–B and A–B compartments.

A quality control of HiChIP data was provided in Supplementary information, Table S6.

ChIA-PET and PLAC-seq data analysis

CTCF ChIA-PET data were downloaded from GEO (GSM2645441), ChIA-PET2 pipeline84 was used to process CTCF ChIA-PET data (‘--linkerA ACGCGATATCTTATC --linkerB AGTCAGATAAGATAT -t 20 -k 1 -C 2 -m 1’). Briefly, adapter sequences were firstly trimmed. Pair-end tags (PETs) were independently aligned to the mm9 reference genomes with bwa-mem.85 Only PETs with MAPQ larger than 30 were retained. All PETs with one copy retained were used to call peaks with MACS276 (version 2.1.2). Pair information is not used in this peak calling step. Peaks with 500-bp extension at both sides were merged as anchors. A PET that links to two different anchors was treated as one putative interaction. Significant interactions were called with R package MICC.86 Contacts with FDR < 0.05 and supported read pairs ≥ 2 were defined as significant interactions. The method for PLAC-seq data processing is consistent with that for CTCF HiChIP.

CTCF-connected A compartments

All CTCF putative interactions were used to call CTCF-connected A compartments using mango and MICC software, respectively. We used all these CTCF putative interactions from CTCF HiChIP data to generate contact matrices at 100-kb resolution. The diagonal-removed matrices were further used as input to call significant interactions using mango or MICC. Pairs of 100 kb unit regions with P ≤ 0.01 or FDR ≤ 0.01 were defined as CTCF-connected regions. Pairs of A compartments with interacting regions inside were defined as CTCF-connected A compartments.

Gene ontology analysis

Gene symbols were first converted to EntrzID with R package BiomaRt87 (version 2.42.0). ‘ensembl’ was used as biomart database, and ‘mmusculus_gene_ensembl’ was used as dataset. EntrzID of interest genes was uploaded to DAVID 6.8.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grants from the National Key R&D Program (2017YFA0102800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970811, 31771639 and 32170798), the Guangdong Regenerative Medicine and Health of Guangdong Laboratory Frontier Exploration Project (2018GZR110105007), the Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (2016ZT06S029), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021B1515120063) to J.D.; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100497) and Post-doctoral Program (2021M703760) to C.W.; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Jinan University (Natural Science) (116210004) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (55350600), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2021A1515010938) to J.S.; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900519) to F.L.; the Natural Science Foundation of China (32025006, 31871266) and National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1100300, 2016YFA0100103) to L.J. and C.L. Part of the data analysis was performed on the High Performance Computing Platform of the Center for Life Sciences, Peking University. This work was also supported in part by the State Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0505503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81890991), CAS Interdisciplinary Innovation Team (JCTD-2020-04), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Z200021) to J.G. For FISH experiment, we thank the help from Morningstar Genes Intelligence Ltd. (MGI Beijing), China, and the effort from Ms. Rui Wang and Ms. Yuyao Song in School of Life Sciences, and in Class of Basic Sciences, Tsinghua Xuetang talent program, Tsinghua University, China. We thank Hongjie Yao for the gift of shRNA targeting Rybp, and thank Guohong Li for the gift of RING1B-AID cell line. We also thank Yuanjun Guan for image data analysis and Yali Tang for FACS analysis.

Author contributions

C.W., L.J., X.H. and J.T. conceived the experiments. C.W., L.J., X.H., J.T., M.W., S.J., Y.H., J.N., L.Q., and L.M. performed the experiments. L.J., P.Z., J.S., X.L., T.L. and C.W. performed the data analysis and statistical calculations. Y.S., and J.G. supervised the design of the FISH probe. C.W., L.J., X.H., J.T., J.W., F.L., L.F., X.T. and J.L. prepared the manuscript. J.D. and C.L. supervised the project.

Data availability