Abstract

In the present study, influence of nitrate concentration on in vitro rooting and its ex vitro hardened tubers were investigated in D. hamiltonii. In vitro multiple shoots established on the MS medium were used as explants for this study and concentration of indole-3-butyric acid (1.23 µM) required for root initiation was determined. The effect of different nitrate concentrations in MS medium for in vitro rooting was investigated and positive (¼ and ½ strength) influence was observed on 14 days inoculation. The in vitro rooted plants (IVP) showed 80% survival upon hardening and exhibited similar growth pattern to seedling plants. The 1-year grew ex vitro hardened plants were evaluated for their tuber quality with reference to their yield and flavor metabolite 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde (2H4MB) content. The IVP grown from ¼ nitrate strength media produced 155 ± 4.85 g FW of tuber biomass which is observed to be higher than full nitrate strength IVP (112 ± 2.52 g) which are grown under similar conditions in the greenhouse. The flavor metabolite content, total phenolics, total flavonoids, and antioxidant potential of these IVP tubers were evaluated. Upregulation of flavor biosynthetic pathway genes DhPAL, DhC4H and DhCoMT were observed in tubers of potted plants that developed from low nitrate strength culture media. In this study, superiority of tissue cultured plants was evident, wherein in vitro plants developed in low nitrate strength medium and acclimatized could produce a higher yield in tuber biomass and maintain relative content of flavor compounds in this endangered plant.

Keywords: Endangered, Endemic, In vitro rooting, Nitrate concentration, 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde

Introduction

Many plant species which have been utilized in indigenous cuisine by the native population for their richness in aroma and bioactives are currently in a state of endangerment. D. hamiltonii (Periplocoideae), which is commonly known as swallow root, is endemic to Western and Eastern Ghats of the Indian sub-continent (1990). The tubers of these plants are widely used by the indigenous communities in the preparation of various traditional recipes, pickles, beverages, (Sharbat, juice), culinary spices, and a natural preservative (Ch et al. 2013). The tuber’s natural flavor and bioactive properties such as antimicrobial, antioxidant activity and insecticidal properties (Pradeep et al. 2016) make it an important ingredient in various indigenous foods. The aromatic flavor of the tubers is due to the presence of a specific compound known as 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde (2H4MB), an analogue of vanillin. Slow propagation in its natural environment and over-exploitation of this plant’s flavored tubers for food and medicinal applications have made it a rare and endangered plant species (Ved et al. 2015). A 2–3-year-old plant is reported to yield 15–20 kg of tubers (Wealth of India 1990). These tubers are sold USD 4.5–5.5 kg−1 fresh weights (FW) during the season and USD 5–8 kg−1 FW in the offseason.

Considering endangered status, alternative methods for its sustainable cultivation using nodal explants (Obul Reddy et al. 2002; Sharma and Shahzad 2012), shoot tips (Giridhar et al. 2005a), in vitro rooting of micro-shoots (Reddy et al. 2001), augmentation of callus biomass and flavor production under in vitro conditions (Umashankar and Giridhar 2022; Umashankar et al. 2022) were reported. Similar, efforts were made to get efficient ex vitro quality tuber by using various biotic, abiotic elicitation (Giridhar et al. 2005b; Matam and Parvatam 2017a, b) production of 2H4MB in normal root cultures in vitro (Giridhar et al. 2005c) and by identifying the key genes (Kiran et al. 2018), proteins (Kamireddy et al. 2021) involved during flavor biosynthesis pathway. However, there are no reports regarding the influence of nitrate (NO3) concentration on swallow root and its tuber growth.

In plants, nitrogen is an important nutrient for its growth and organogenesis. In plant tissue culture, the culture media used for in vitro propagation constitutes potassium nitrate and ammonium nitrate which are the primary sources of nitrogen (Ghoochani Khorasani et al. 2022). The nitrate concentration in the culture media plays a major role in a shoot to root growth proliferation. Understanding the role of nitrate in the development of in vitro roots will be very useful for the mass production of in vitro plants of this endangered plant. Nitrate concentration in media showed a good rooting response from shoot cultures in plant species like Passiflora foetida (Shekhawat et al. 2015) Decalepis salicifolia (Rodrigues et al. 2020) and Oryza sativa (Kumar et al. 2020).

Accordingly, in the present study, investigations were carried out to determine the influence of nitrate concentration on the induction of in vitro rooting and it is ex vitro hardened tubers in D. hamiltonii. The quality of ex vitro hardened tubers is determined in terms of biomass, flavor metabolites, and antioxidant potential. The expression levels of flavor biosynthetic pathway genes DhPAL, DhC4H and DhCoMT in in vitro plant tubers were analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture conditions

Axillary buds were washed under running tap water to remove superficial contamination. Single bud explants (1 cm each) from the anterior portion of the shoots were washed with Tween 20 (5% v/v) for 5 min, followed by thorough washing under running tap water for 15 min. The explants were surface sterilized with 0.15% (w/v) mercuric chloride for 3 to 5 min and rinsed 4 or 5 times with sterile distilled water. Explants were inoculated onto Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) fortified with 4.4 μM BA and 0.54 μM NAA (Reddy et al., 2001). The pH was adjusted to 5.8 ± 0.2 before gelling with 0.8% (w/v) of agar (Hi media, Mumbai, India). The conical flasks (150 ml capacity) containing medium (40 ml) were covered with non-absorbent cotton plugs, and autoclaved under 1.06 kg/cm−2 pressure at 121 °C for 15 min. Explants were inoculated and kept for culturing at an incubation temperature of 25 ± 2 °C and 45 µmol m−2 s−1 light for 16 h photoperiod for 8 weeks using fluorescent lights (Philips India Ltd, Mumbai). These in vitro established plants served as the source for the rooting experiment.

In vitro rooting at different nitrate concentration

The nitrate influence on in vitro rooting was investigated in two steps (i) by determining the minimum auxin concentration required for rooting and (ii) to evaluate the rooting response under nitrate concentration. In the first step, the minimal auxin concentration required for root initiation was determined and at this concentration, the influence of nitrate for in vitro rooting was investigated. The multiple shoot explants (0.5–1 cm) which are cultured for 3–4 weeks obtained from shoot induction media were used for in vitro rooting. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) was used for root initiation in MS medium (full strength) with 3% sucrose at different concentrations (0, 0.04, 0.4, 1.23, 2.45 µM). Depending on rooting response, root number, the root length, the optimum concentration was determined.

At optimized IBA concentration, the nitrate salt content in the MS media (KNO3, NH4NO3) was reduced to ¼ nitrate strength (4.7 mM KNO3, 5.15 mM NH4NO3), ½ nitrate strength (9.4 mM KNO3, 10.3 mM NH4NO3), ¾ nitrate strength (14.1 mM KNO3, 15.45 mM NH4NO3) levels and observed for rooting. MS medium with full strength nitrate (18.8 KNO3, 20.6 mM NH4NO3), and MS medium without nitrate content were also made used in the experiment to observe the rooting response. These plant cultures were maintained at 25 ± 2 °C under 45 µmol.m−2 s−1 light at 16 h photoperiod.

Greenhouse hardening of plantlets

Three months old in vitro established rooted plants (IVP) which are 12–15 cm long grown under different nitrate concentrations (¼, ½, and ¾ NO3 strength) were hardened in a greenhouse along with plantlets grown in full-strength nitrate (25 No) for 2 weeks. Acclimatization of these plants was made to pots containing soil: sand: manure (2:1:1). The plantlets after acclimatization were grown for 1 year and its tubers weight, biochemical content and expression profile of 2H4MB biosynthesis pathways genes were observed. Simultaneously, 80–100 seeds of D. hamiltonii were germinated in a greenhouse. The germinated 1-month-old seedling plants (“SP”) were transplanted to individual pots (one plant/pot) containing soil in the above ratio. These grown seedling plants after reaching 12–15 cm in length later used in the experiment (25 No). The experiment sampling was taken between groups as independent measures, where individual plant samples in each condition are taken as the independent variables.

Quantification of flavor compound by HPLC

Flavor compound in tubers 2H4MB was quantified using the HPLC method as reported earlier (Matam and Parvatam 2017a; Pradeep et al. 2019). A known quantity of tubers (50 g Dry weight) obtained from 1-year-old plants was subjected to steam distillation. The condensate obtained after distillation was extracted with dichloromethane and flavor metabolite quantified with HPLC (SPD-20AD, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using a C18 (250 × 4.6 mm 5-µm diameter) column (SunFire column, Waters USA). The concentration of metabolite in the sample was determined by comparing the peak area with standard 2H4MB (Sigma-Aldrich USA) concentration.

Determination of total phenolics

The total phenolic content in methanol extracts of plant tubers was determined by spectrometry using “Folin-Ciocalteu’s” reagent assay (Sadasivam and Manickam 2008). The 80% methanol extract from the tuber was mixed with Folin Ciocalteau’s reagent followed by 20% Na2CO3 solution. After incubation, samples were measured for phenolic content at 650 nm and expressed in terms of Gallic Acid Equivalent (mg GAE g−1 extract).

Determination of total flavonoids

The sample’s total flavonoid content was estimated using the spectrophotometric method as reported by Pradeep et al. (2019). The flavonoid content in 80% methanol extract of plant tubers was determined and expressed in terms of Quercetin Equivalent (QE) mg g−1 extract.

Antioxidant activity

DPPH assay

The methanol extracts from tubers were determined for Free radical scavenging potential using DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay. Samples of different concentrations were mixed with 0.1 mol L−1 DPPH reagent, and after incubation absorbance was measured at 517 nm (Srivastava et al. 2006).

Nitrate oxide assay

The nitric oxide generated in reaction with sodium nitroprusside is measured with the addition of Griess reagent (Srivastava et al. 2007). Sample methanol extract of different concentrations was mixed with 5 mM sodium nitroprusside and incubated. To the mixture, Griess reagent was added and changes in absorbance was measured at 546 nm.

Gene expression analysis

RNA was extracted from the root, and tubers using spectrum plant Total RNA kit, (Sigma, USA) and cDNA was synthesized (cDNA kit, Thermo Scientific, Lithuania). Gene-specific primers which were optimized from our previous studies was used for expression studies (Kiran et al. 2018). The experiments were carried in real-time Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase chain reaction qRT-PCR (AppliedBiosystems QuantStudio5, Singapore) and relative fold change in gene expression during plant growth was calculated using the 2ΔΔct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Statistics

To induce rooting at different nitrate concentrations, 25 shoot explants were used during the study. The experiment was repeated twice. The average root number and root length were noted (± SE of five replicates) and subjected to one-way ANOVA. After ex vitro hardening, respective tuber extracts from three plants were used for the analysis of metabolites. For each extract, three analyses were performed (± SE) and the significance were calculated by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.01) using Graphpad Prism version 5 software.

Results

Optimization of IBA on in vitro rooting

In the present study, initial efforts were made to optimize the appropriate auxin concentration required for efficient in vitro rooting to 8-week-old micro-shoots of D. hamiltonii. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) was used for root initiation in MS medium (full nitrate strength) at different concentrations (0, 0.04, 0.4, 1.23, 2.45 µM). Incorporation of 1.23 µM concentration of IBA in MS medium (Table 1) induced maximum response (90%) for in vitro rooting with 15 ± 1.3 mm root length and 2.1 ± 0.9 root number by 6 weeks after inoculation. Whereas, IBA at 0, 0.04 µM concentration in MS medium shoots did not show any response with no morphological changes but remained green even after 8 weeks. 70% response for rooting was observed in shoots grown on MS medium containing 2.45 µM IBA with 13 ± 1.4 mm root length and 2 ± 0.8 root numbers by 6 weeks. In MS medium with IBA 0.4 µM concentration rooting response was observed to be 50% with 3.5 ± 1.3 mm root length and 1 ± 0.5 root numbers by 6 weeks. At 1.23 µM and 2.45 µM IBA concentrations the average number of roots and root length is not significantly different. However, the growth rate, and rooting response were observed to be slow at 2.45 µM IBA concentration.

Table 1.

Optimization of minimum auxin concentration required for initiation of in vitro roots in D. hamiltonii

| Concentration of IBA (µM) |

Explants response for rooting (%) | Root number (explant −1) |

Root length (mm explant −1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.4 | 50 | 1 ± 0.5b | 3.5 ± 1.3c |

| 1.23 | 90 | 2.1 ± 0.9a | 15 ± 1.3a |

| 2.45 | 70 | 2 ± 0.8a | 13 ± 1.4b |

Results are reported as Mean ± SE of 10 replicates. Duncan Multiple Range Test was used to determine Significance (p < 0.01) and values with the same superscript were not significantly different from each other

Rooting under nitrate effect

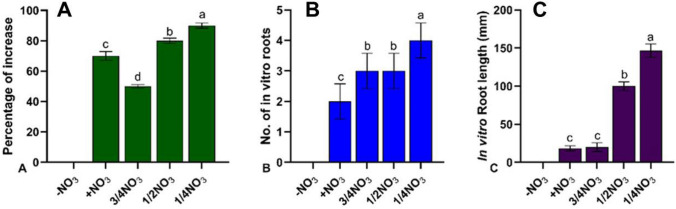

The reduced nitrate concentrations positively influenced the induction of rooting (Fig. 1A, B). After the 14th day of inoculation, rooting was evident from explants in MS medium comprising ¼ or ½ strength nitrate salts. (Fig. 2A). Whereas in explants inoculated on ¾ and full nitrate strength salts medium, slow induction of rooting after 20th day was observed. The percentage of shoot explants which responded to in vitro rooting was highest (85%) on MS medium containing ¼ strength of nitrate salts followed by medium containing ½, ¾ and full-strength nitrate salt. Similarly, root number and root length was high on medium with ¼ nitrate salts (Fig. 1B). In explants inoculated on ¾ and full-strength nitrate medium, very fast shoot growth was observed in comparison to other levels of nitrate medium. Whereas in ¼ and ½ nitrate strength medium, shoot length growth was slow and did not show any other stress symptoms of nitrate deficiency. The plantlets which are grown for 3 months have shown the production of a tuft of long roots with 100–150 mm root length in ¼ and ½ strength media (Fig. 2C). Explants grown on medium without nitrate salts could not survive, whereas explants grown on full-strength nitrate MS medium devoid of IBA slow shoot growth without rooting was observed. Among the five different nitrate concentrations in the culture medium, the response for plants obtained in ¼ strength nitrates comprising medium exhibited significant response, for the percentage of increase in rooting, number of roots and length of roots, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

D. hamiltonii in vitro rooting at different nitrate concentration A Percentage increase of rooting B, C Root length (mm) and root number after three months (mean ± SE of five replicates, significant at p < 0.01)

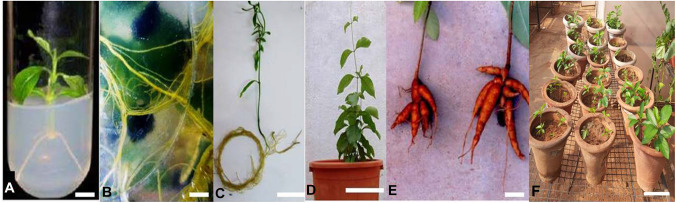

Fig. 2.

A Initiation of rooting from in vitro shoot of D. hamiltonii on ¼ nitrates strength MS medium with 1.23 µM IBA (bar = 5 cm) B Magnified view of long roots and root hairs that emerged from in vitro micro shoot on medium bearing ¼ nitrate strength with 1.23 µM IBA (view from bottom of culture bottle, (bar = 5 cm) C Three months old in vitro plant grown on ¼ nitrates strength MS medium with a tuft of 146.6 ± 8.8 mm long roots (bar = 15 cm) D Hardened in vitro rooted plant after 12 months (bar = 25 cm) E Tubers of one year old uprooted from seedling plant (left) and in vitro rooted and hardened plant (right) (bar = 20 cm) F Seedling plants germinated in greenhouse (bar = 15 cm)

Hardening of in vitro rooted plants (IVP) in the greenhouse showed 80% survival after acclimatization (Fig. 2D). Both seedling plants (SP), in vitro developed plants (IVP) almost have similar growth characteristics. In the present study, it was observed that fresh weight (FW) of tubers collected from ¼ NO3 strength IVP was observed to have the highest tuber biomass (155 ± 4.85 g) than full NO3 strength IVP tuber biomass (112 ± 2.52 g) after 1-year growth (Fig. 2E). The 1-year-old tubers biomass weight obtained from ¾, and ½ nitrate salts grown IVP were observed to be 130 ± 3.10 g and 142 ± 5.28 g, respectively. Similarly, the tuber biomass produced from SP tubers which that were grown under the similar conditions and same age showed 105 ± 5.46 g FW. The observations obtained were taken from five sets of plants and the mean average value was reported.

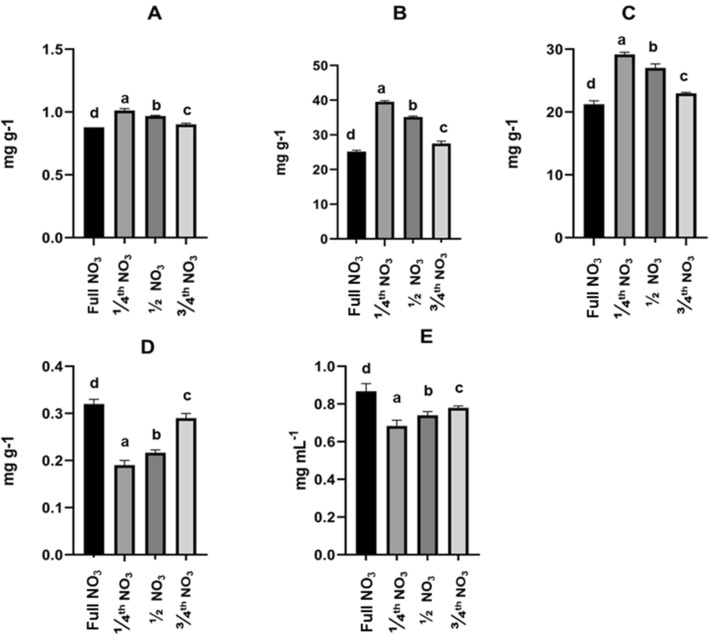

Quantitative evaluation of 2H4MB content

One-year-old ex vitro hardened plant tubers obtained from both in vitro plants grown in different nitrate strength media tubers were analyzed for 2H4MB content. It was observed that ¼ NO3 in vitro grown tubers showed 1.021 ± 0.061 mg g−1 DW of 2H4MB that was found more than that of full NO3 strength IVP tubers of same age 0.864 ± 0.05 mg g−1 DW. (Fig. 3). All IVP tubers grown from different nitrate concentration media showed higher 2H4MB content compared to full NO3 IVP grown tubers. The decreasing order of 2H4MB content in tubers are ¼ NO3, ½ NO3, ¾, NO3, and full NO3 IVP tubers, respectively. The amount of 2H4MB content in tubers of SP tubers is observed to be 0.964 ± 0.05 mg g−1 DW, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Biochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of tubers of D. hamiltonii IVP plants A 2H4MB (mg g−1), B Phenolics (mg g−1), C Flavonoid (mg g−1) D DPPH assay (IC50 mg mL−1), E Nitrate oxide assay (IC50 mg mL−1). The values are an average of three analyses (± S.D.); values are significant at p < 0.01. (n = 3) are the plant numbers used for obtaining tuber extracts for analysis

Quantification of total phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant activity

Total phenolics and flavonoid content in tuberous roots of one year grown plants were observed to be varied in IVP tubers (Fig. 3). There was a progressive increase for both phenolics and flavonoid content in plants that are grown from different nitrate media. The decreasing order of total phenolics and flavonoid content in tuberous roots is ¼ NO3, ½ NO3, ¾ NO3, full NO3 IVP tubers, respectively. The ¼ NO3 strength IVP tubers have shown the highest amount of phenolics (39.9 ± 1.02 mg g−1) and flavonoids (29.5 ± 1.14 mg g−1) among IVP tubers. The seedling plants tubers of same age contain 39.1 ± 0.2 mg g−1 phenolics and 27.8 ± 0.5 mg g−1 flavonoids (Table 2).

Table 2.

Flavor contents and biochemical analysis of 1-year-old D. hamiltonii seedling-plant tubers that grown in greenhouse

| Source | 2H4MB content (mg g−1) |

Phenolics (mg g−1) |

Flavonoids (mg g−1) |

DPPH (IC50 in mg mL−1) |

NO (IC50 in mg mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seedling plant (SP) tubers | 0.954 ± 0.01 | 39.1 ± 0.2 | 27.8 ± 0.5 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.08 |

The values are average mean triplicates (± S.D.) and are significant at (n = 3) are the plant numbers used for obtaining tuber extracts for analysis

The methanol extract H+ radical scavenging is a vital aspect of an antioxidant assay, which is measured by the DPPH assay. The methanol extracts of plants reduce the DPPH, which will be indicated with color change which will be measured at 517 nm and the IC50 value will be determined. This IC50 value was observed to be low for tuber extracts from ¼ NO3 treated and exhibited strong antioxidant property (0.18 ± 0.04 mg g−1). The IC50 value of different tuber extracts is shown in Fig. 3. A similar response for NO assay was evident (0.65 ± 0.06 mg g−1) in ¼ NO3 tubers. The remaining in vitro plant tubers have shown lower IC50 content than the ¼ NO3 treatment based tubers methanol extract.

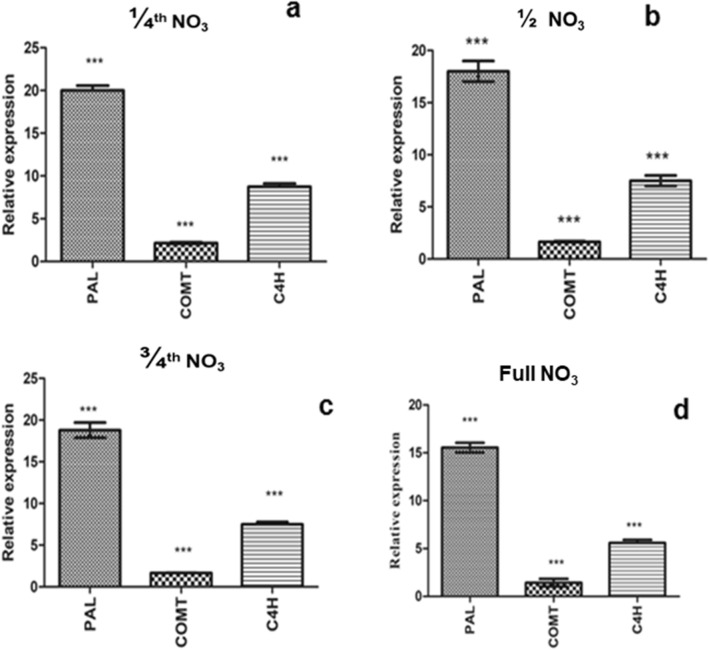

Gene expression analysis of phenylpropanoid pathway (PPP) genes after nitrate stress

The expression analysis of three major PPP genes Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (DhPAL), Cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (DhC4H), Caffeic acid- O-methyl transferase (DhCOMT) which are involved in 2H4MB biosynthetic pathway was analyzed in IVP tubers using qRT-PCR. The Actin gene was used as the reference gene in the quantification of the expression of desired genes. The fold change in the relative expression of genes of IVP tubers was calculated in comparison to acclimatizing in vitro plantlets that are grown from low nitrogen media (Fig. 4). The expression level of DhPAL, DhC4H and DhCOMT of ¼ NO3 tubers in comparison with control (acclimated plantlet) are observed to be 20, 8.7, 2.15 folds, whereas in full NO3 tubers was 15.5, 5.6, and 1.4, respectively, compared to its control. The analyses showed that the expression of the DhPAL, DhC4H, and DhCOMT genes was significantly upregulated in IVP tubers of which are grown from different concentrations of nitrate strength media.

Fig. 4.

Relative Gene expression of phenylpropanoid pathway genes DhPAL, DhCoMT, DhC4H of in vitro grown plant tubers analyzed by qRT-PCR. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM for triplicate. a Plants grown in ¼ nitrate strength MS media. b Plants grown on ½ nitrate strength MS media. c Plants grown on 3/4 nitrate strength MS media. d Plants grown on full nitrate strength MS media. The expression results were normalized with respect to the control housekeeping genes using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001

Discussion

A positive response for in vitro rooting from micro-shoots of D. hamiltonii was observed under the influence of nitrate concentration in the culture medium. The low concentration of nitrates (¼ strength) supported efficient in vitro rooting from shoots, leads to production of quality tubers upon field transfer. (Kumar et al. 2020; Ghoochani Khorasani et al. 2022). On the basis of preliminary studies for rooting response from micro-shoots, IBA was selected for induction of rooting from micro-shoots under varied levels of nitrate stress.

Depending on the response for in vitro rooting, root length, and root number the concentration of IBA was optimized. Whereas, IBA at lower concentrations did not show any response with no morphological changes observed. In other IBA concentrations (1.2, 2.45), the average number of roots and root length is not significantly different. However, the rooting response, and growth rate was observed to be slow at higher concentration; this may be due to an increase in the concentration of the hormone. IBA was reported to be widely used in commercial horticultural plant rooting (Giridhar 2007) as an ingredient in plant propagation media (Giridhar et al. 2001), as it is used to induce adventitious rooting from the stem. IBA inhibits primary root elongation and stimulates lateral root formation (Frick and Strader 2018). Similarly, in our study, lateral roots were observed during the initial stage of in vitro rooting, but later a tuft of roots developed from the shoot. IBA is reported to be converted to IAA in a process similar to fatty acid β-oxidation in peroxisome (Damodaran and Strader 2019). Some studies showed IBA was effective in inducing rooting in D. salicifolia (Gangaprasad et al. 2005) and D. arayalpathra (Ahmad et al. 2018) plants which belong to the same family. IBA in relation to nitrate concentration gave good rooting response in D. salicifolia (Rodrigues et al. 2020).

In the present study, MS basal media without nitrate was used as negative control, and full nitrate strength (normal nitrate concentration) was taken as a positive control. The micro-shoots were inoculated into respective media and root initiation were observed in a concentration -dependent manner at different time intervals. The rooting response in low nitrate media was observed to be faster than with media with higher concentration. Similarly, root number and root length and growth response was also observed in concentration dependent manner. In explants inoculated on high nitrate medium (¾ and full), very fast shoot growth was observed in comparison to other levels of nitrate medium. Whereas in low nitrate strength medium (¼, ½), shoot length growth was slow and did not show any other stress symptoms of nitrate deficiency. The plantlets which are grown for 3 months have shown the production of a tuft of elongated roots. Explants grown on medium without nitrate salts could not survive whereas explants grown on full-strength nitrate MS medium devoid of IBA showed shoot growth without rooting. The nitrogen concentration (nitrate and ammonium) and the carbon/nitrogen ratio of the in vitro culture medium show great influence on plant growth and its synthesis of secondary metabolites (Bensaddek et al. 2001). In plants, when the nitrate reserves are reduced, root development is given priority over shoot growth and has a high influence on the relative growth of the plant root system (Seginer 2003; Roycewicz and Malamy 2012; Zhang et al. 2012). Whereas, the high nitrate concentrations were reported to decline in vitro hairy root growth and increase in other metabolites (Chashmi et al. 2010). The long roots obtained in vitro under nitrate stress is further supported by a similar study that described how nitrate starvation induces root elongation in rice (Zhang et al. 2012). At this juncture, it could be hypothesized that the influence of low nitrates on the plant in vitro root growth and its high-quality tubers development could be attributed to an alteration in the expression pattern of respective plant growth regulators. Moreover, the response under low nitrates in medium i.e., osmotic changes is further supported by an enhanced nutrient uptake and a respective carbon source such as sucrose which promotes healthy growth of plants as reported for potatoes (Wojtania et al. 2019). Similarly, in Cecropia peltata, the carbon assimilated during photosynthesis due to light, and nitrate stress, shows the structural change in different organs (biomass) and secondary metabolites accumulation (Izquierdo et al. 2011). Recently, a similar type of observations was reported on other species of Decalepis which showed the difference in type and nature of in vitro roots in comparison to D. hamiltonii (Rodrigues et al. 2020).

The plantlets which are grown for three months with good elongated roots were acclimatized to the greenhouse for hardening. In D. hamiltonii in our previous study, we have reported the production of flavor metabolite is good at 3 months (Kiran et al. 2018). In the present study, the in vitro grown plants were hardened for 2 weeks and then transferred to pots. Simultaneously, seedling plants (“SP”) were established in the greenhouse. The seedling plants (SP) were established to observe changes between “SP” and “IVP” during growth. The explants (multiple shoots) used for the rooting experiments and seeds of seedling plants are taken from the same parent plant and are used for comparing tuber yield and quality. In the seedling plants after 3 months’ growth, 3–4 roots of 6–10 cm in length were evident. This was based on the observations of five such plants. Upon transplanting into bigger pots, and continuing the growth until 12 months, just like that of in vitro-based plants, the number of tubers was counted. It was found that, the number of tubers were more (6–7 No.) compared to the initial root number at 3 months (3–4 No.), thus inferring that root number increased during the subsequent growth of these plants. Along with this, root hairs’ presence is a general phenomenon noted. The trend was more or less the same for both the SP and IVP, except for the tuber biomass and variation in flavour content and biochemical.

It was observed that in “SP” tuber was developed initially from single taproot and later slowly lateral roots were developed once mother root stop growing and in IVP plants tubers started developing from all the adventitious roots randomly. This may be the reason for an increase in tuber biomass in all IVP plants. The tubers’ quality was determined in terms of their biomass, total phenolic, total flavonoids and flavor metabolite 2H4MB content along with its antioxidant potential. Furthermore, relative gene expression was analyzed for candidate genes involved in 2H4MB biosynthesis pathways. In tissue culture, medium nitrates and ammonia are the commonly used nitrogen sources and the type of nitrogen source influences uptake of other nutrients (Schmitz and Lorz 1990), which was well documented in potatoes wherein preferential uptake of nitrate over ammonia was observed (Davis et al. 1986). Potato is an important staple crop, extensive studies on the effect of nitrates on tuber yield, weight and size were investigated (Chen and Liao 1993; Kolachevskaya et al. 2019). Apart from this, ex vitro leaves photosynthesis is having considerable influence on tuber growth and yield was also reported (Kolachevskaya et al. 2019). It is a well-accepted fact that in vitro leaf photosynthesis is mostly lower to ex vitro due to physiological stress or alteration in plant growth. The effect of nitrogen stress and the resulting physiological and biochemical responses in lettuce (Seginer et al. 1999; Seginer 2003) and tomato (Ezzine and Ghorbel 2006), were reported as model systems. A similar type of response was found in our study for swallow root with reference to shoot growth (data not shown), but at the same time, its effect on root induction was positive with more long roots. All these observations could also be attributable to the tuber growth of D. hamiltonii. Overall, in the present study, reduced nitrates concentration in the culture medium helps to bring down the expenditure. To produce 1000 no. of in vitro rooted plants on MS medium with normally used full nitrates it may cost 747 USD. By reducing the nitrates concentration in the medium to 1/4th strength, we could able to bring down the cost by 468 USD (2.8 folds less) for 1000 no of rooted plants.

Methanol extract of D. hamiltonii is reported to have high antioxidant activity which can be determined by measuring its free scavenging radicals and reducing power activity (Srivastava et al. 2006). In the present study, there was a progressive increase in both phenolics and flavonoid content in IVP plant tubers which are grown from different nitrate media. Plants grown from low nitrogen media showed accumulation of high secondary metabolites and increased levels of lignin. These secondary metabolites, phenylpropanoids are reported to be synthesized from phenylalanine (Fritz et al. 2006). These metabolites have functional groups like hydroxyl groups and often produce free radicals such as O2, H2O2, OH and NO which have redox potential due to which it shows high antioxidant potential. The methods like NO reduction are often used as an indicator of electron-donating activity (Huang et al. 2005) and the DPPH assay which accepts electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule (Soare et al. 1997), is usually used as a substrate to evaluate the antioxidant activity. A lower value of IC50 indicates a higher antioxidant activity. Earlier reports demonstrated that some of the plant’s root-based extracts have scavenging free radicals which is mainly due to their rich polyphenols and other phytochemicals (Murthy et al. 2006; Srivastava et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2015). The tuber extract with high antioxidant potential lessens the oxidative stress can serve as source of nutraceuticals and has potential food applications.

Flavour content in the tubers of D. hamiltonii is reported to be produced through the phenylpropanoid pathway (Kamireddy et al. 2017; Kiran et al. 2018) and the major phenylpropanoid pathway genes expressed were analyzed in IVP tubers. Three major genes involved were evaluated in IVP tubers which are grown in low nitrate and full nitrate (Control plant) IVP plant. DhPAL gene has shown high expression in all IVP tubers grown from lower nitrate concentration media in comparison to plants grown from full nitrate. This high expression may be responsible for increased production of phenylpropanoid metabolites which in turn leads to the production of high tuber biomass and flavor metabolite. The expression level of the DhC4H showed a constant level of expression in all IVP tubers. Similarly, the increased expression of DhCOMT in IVP tubers is directly correlated to the flavour development and also mediates tuber maturation. In all IVP tubers grown from low nitrate media, flavonoid content was observed to be higher in comparison to full nitrate plants. In plants, during stress conditions, phenylpropanoids are reported to have a high influence in monitoring of plant physiology and metabolism. These metabolites induce tolerance during the stress conditions in reducing oxidative stress and help in plant survival (Francini et al. 2019). During low nitrogen content phenylpropanoid pathway is induced by removing nitrogen from phenylalanine. This important step was reported to be regulated by phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) gene (Olsen et al. 2008; Izquierdo et al. 2011). The PAL gene expression in plants increases during abiotic stress to replenish amine from phenylalanine which is used in the production of new amino acids. The Cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H) gene is a key enzyme reported to involving a constant role in tuber development and flavour synthesis of D. hamiltonii (Kiran et al. 2018). Similarly, Izquierdo et al. (2011) reported high expression of PAL C4H and 4CL in plants grown in nitrate deficiency. Another important phenylpropanoid pathway gene COMT is reported to involve in the biosynthesis of different metabolites which include monolignols, (Inoue et al. 1998) and vanillin (Gallage et al. 2014), and 2H4MB (Kamireddy et al. 2017). The gene Caffeic acid-O-methyl transferase (COMT) catalysis the formation of ferulic acid (Pichersky and Gang 2000), which is an important precursor molecule in flavor production also reported to mediate tuber development through lignification, where the parenchyma cells in roots develop into storage cells by lignification (Sirju-Charran and Wickham 1988). In maize, high expressions of the COMT in roots were reported (Collazo et al. 1992), and in ryegrass, its expression is more in stem (McAlister et al. 1998). Brachypodium and wheat plants show differential pattern expression in their tissues (Wu et al. 2013). Lea et al. (2007) examined flavonoid pathway gene expression under nitrogen deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. They reported an increase in the expression of transcription factors and flavonoid pathway compounds in plants grown with nitrogen deficiency.

Conclusion

The results suggest that rooting under low nitrate concentration has a substantial and sustainable influence on the quality parameters of tubers. The in vitro rooted shoots are successfully field transferred which is crucial for the propagation of this endangered plant. The outcome of this study is worthy, since a good yield in tuber biomass is vital in rendering the propagation protocol for these economically important tubers.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Science & Engineering Research Board (SERB), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) Government of India, New Delhi for the research Grants EMR_2016_001049 and 12 FYP-Network Program-BSC0106, respectively.

Author contributions

KU: investigation, analysis, and compiling the data. MP: conceptualization, investigation, analysis, manuscript writing. PG: funding acquisition, overall supervision of research work, interpretation, writing and editing.

Funding

The study was supported by SERB, CSIR Government of India, New Delhi for the research Grant EMR_2016_001049 and 12 FYP-Network Program-BSC0106, respectively.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad Z, Shahzad A, Sharma S. Enhanced multiplication and improved ex vitro acclimatization of Decalepis arayalpathra. Biol Plant. 2018;62:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10535-017-0746-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaddek L, Gillet F, Saucedo JEN, Fliniaux M-A. The effect of nitrate and ammonium concentrations on growth and alkaloid accumulation of Atropa belladonna hairy roots. J Biotechnol. 2001;85:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch M, Reddy R, Murthy KSR. A review on Decalepis hamiltonii Wight Arn. J Med Plant Res. 2013;7:3014–3029. doi: 10.5897/JMPR2013.5099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chashmi NA, Sharifi M, Karimi F, Rahnama H. Differential production of tropane alkaloids in hairy roots and in vitro cultured two accessions of Atropa belladonna L. under nitrate treatments. Z Naturforsch. 2010;65:373–379. doi: 10.1515/znc-2010-5-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Liao YJ. Nitrogen-induced changes in the growth and metabolism of cultured potato tubers. J AM Soc Hortic Sci. 1993;118:831–834. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.118.6.831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collazo P, Montoliu L, Puigdomènech P, Rigau J. Structure and expression of the lignin O-methyltransferase gene from Zea mays L. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:857–867. doi: 10.1007/BF00027157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran S, Strader LC. Indole 3-butyric acid metabolism and transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front in Plant Sci. 2019;10:851. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Loescher WH, Hammond MX, Thornton RE. Response of potatoes to nitrogen form and to change in nitrogen form at tuber initiation. J AM Soc Hortic Sci. 1986;111:70–72. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.111.1.70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzine M, Ghorbel MH. Physiological and biochemical responses resulting from nitrite accumulation in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Ibiza F1) J Plant Physiol. 2006;163:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francini A, Giro A, Ferrante A. Chapter 11 - Biochemical and molecular regulation of phenylpropanoids pathway under abiotic stresses. In: Khan MIR, Reddy PS, Ferrante A, Khan NA, editors. Plant Signaling Molecules. Woodhead Publishing; 2019. pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Frick FM, Strader CL. Roles for IBA-derived auxin in plant development. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(2):169–177. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz C, Palacios-Rojas N, Feil R, Stitt M. Regulation of secondary metabolism by the carbon–nitrogen status in tobacco: nitrate inhibits large sectors of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant J. 2006;46:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallage NJ, Hansen EH, Kannangara R, Olsen CE, Motawia MS, Jorgensen K, Holme I, Hebelstrup K, Grisoni M, Moller BL. Vanillin formation from ferulic acid in Vanilla planifolia is catalysed by a single enzyme. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangaprasad A, William Decruse S, Seeni S, Nair GM. Micropropagation and ecorestoration of Decalepis arayalpathra (Joseph & Chandra.) Venter—An endemic and endangered ethnomedicinal plant of Western Ghats. Ind J of Biotechnol. 2005;4:265–270. [Google Scholar]

- GhoochaniKhorasani A, Roohollahi I, Golkar P. Effect of different concentrations of nitrogen and 2, 4-D on callus and plantlet production of Zamioculcas zamiifolia Engl under in vitro condition. J Hortic Sci. 2022;35:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar P. Micro propagation of vanilla: a foremost orchid spice crop of humid tropics. J Ind Bot Soc. 2007;86:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar P, Reddy BO, Ravishankar GA. Silver nitrate influences in vitro shoot multiplication and root formation in Vanilla planifolia Andr. Curr Sci. 2001;81:1166–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar P, Gururaj HB, Ravishankar GA. In vitro shoot multiplication through shoot tip cultures of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn., a threatened plant endemic to Southern India. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Plant. 2005;41:77–80. doi: 10.1079/IVP2004600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar P, Rajasekaran T, Ravishankar GA. Improvement of growth and root specific flavour compound 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde of micropropagated plants of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn., under triacontanol treatment. Sci Hortic. 2005;106:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2005.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giridhar P, Rajasekaran T, Ravishankar GA. Production of a root-specific flavour compound, 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde by normal root cultures of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight and Arn (Asclepiadaceae) J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:61–64. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1841–1856. doi: 10.1021/jf030723c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Sewalt VJ, Ballance GM, et al. Developmental expression and substrate specificities of alfalfa caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase and caffeoyl coenzyme A 3-O-methyltransferase in relation to lignification. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:761–770. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo AM, del Torres MPN, Jiménez GS, Sosa FC. Changes in biomass allocation and phenolic compounds accumulation due to the effect of light and nitrate supply in Cecropia peltata plants. Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33:2135. doi: 10.1007/s11738-011-0753-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamireddy K, Matam P, Priyanka PS, Parvatam G. Biochemical characterization of a key step involved in 2H4MB production in Decalepis hamiltonii. J Plant Physiol. 2017;214:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamireddy K, Sonbarse PP, Mishra Shashank K, Agrawal L, Chauhan PS, Lata C, Parvatam G. Proteomic approach to identify the differentially abundant proteins during flavour development in tuberous roots of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. 3 Biotech. 2021;11:173. doi: 10.1007/s13205-021-02714-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran K, Sonbarse PP, Veeresh L, Shetty NP, Parvatam G. Expression profile of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in Decalepis hamiltonii tuberous roots during flavour development. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:365. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1388-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolachevskaya OO, Lomin SN, Arkhipov DV, Romanov GA. Auxins in potato: molecular aspects and emerging roles in tuber formation and stress resistance. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:681–698. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Kim SH, Priatama RA, et al. NH4+ Suppresses NO3–-dependent lateral root growth and alters gene expression and gravity response in OsAMT1 RNAi mutants of rice (Oryza sativa) J Plant Biol. 2020;63:391–407. doi: 10.1007/s12374-020-09263-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lea US, Slimestad R, Smedvig P, Lillo C. Nitrogen deficiency enhances expression of specific MYB and bHLH transcription factors and accumulation of end products in the flavonoid pathway. Planta. 2007;225:1245–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Lee JM, Lee S-H, Kim SM, Cha SW. Comparison of artemisinin content and antioxidant activity from various organs of Artemisia species. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2015;56:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s13580-015-0143-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matam P, Parvatam G. Putrescine and polyamine inhibitors in culture medium alter in vitro rooting response of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2017;128:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s11240-016-1108-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matam P, Parvatam G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi promote enhanced growth, tuberous roots yield and root specific flavour 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde content of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus. 2017;16:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister FM, Jenkins CLD, Watson JM. Sequence and expression of a stem-abundant caffeic acid O-methyltransferase cDNA from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Functional Plant Biol. 1998;25:225–235. doi: 10.1071/pp97127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy KNC, Rajasekaran T, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA. Antioxidant property of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44(10):832–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obul Reddy B, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA. The effect of triacontanol on micropropagation of Capsicum frutescens and Decalepis hamiltonii W & A. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002;71:253–258. doi: 10.1023/A:1020342127386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen KM, Lea US, Slimestad R, Verheul M, Lillo C. Differential expression of four Arabidopsis PAL genes; PAL1 and PAL2 have functional specialization in abiotic environmental-triggered flavonoid synthesis. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165:1491–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky E, Gang DR. Genetics and biochemistry of secondary metabolites in plants: an evolutionary perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep M, Kiran K, Giridhar P. A Biotechnological perspective towards improvement of decalepis hamiltonii: potential applications of its tubers and bioactive compounds of nutraceuticals for value Addition. In: Shahzad A, Sharma S, Siddiqui SA, editors. Biotechnological strategies for the conservation of medicinal and ornamental climbers. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep M, Shetty NP, Giridhar P. HPLC and ESI-MS analysis of vanillin analogue 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde in swallow root – the influence of habitat heterogeneity on antioxidant potential. Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus. 2019;18:21–28. doi: 10.24326/.2019.2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BO, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA. In vitro rooting of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn., an endangered shrub, by auxins and root-promoting agents. Curr Sci. 2001;81:1479–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues V, Kumar A, Gokul S, Verma RS, Rahman L, Sundaresan V. Micropropagation, encapsulation, and conservation of Decalepis salicifolia, a vanillin isomer containing medicinal and aromatic plant. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2020;56(4):526–537. doi: 10.1007/s11627-020-10066-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roycewicz P, Malamy JE. Dissecting the effects of nitrate, sucrose and osmotic potential on Arabidopsis root and shoot system growth in laboratory assays. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B, Biol Sci. 2012;367:1489–1500. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivam S, Manickam A. Biochemical Methods, 3rd. New Delhi, India: New Age International Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz U, Lorz H. Nutrient uptake in suspension cultures of gramineae. II. Suspension cultures of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Sci. 1990;66:95–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(90)90174-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seginer I. A dynamic model for nitrogen-stressed lettuce. Ann Bot. 2003;91:623–635. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seginer I, Buwalda F, Straten G. Lettuce growth limited by nitrate supply. Acta Hortic. 1999 doi: 10.17660/1999.507.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Shahzad A. Encapsulation technology for short-term storage and conservation of a woody climber, Decalepis hamiltonii Wight and Arn. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2012;111:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11240-012-0183-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhawat MS, Kannan N, Manokari M, Ravindran CP. In vitro regeneration of shoots and ex vitro rooting of an important medicinal plant Passiflora foetida L. through nodal segment cultures. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2015;13:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirju-Charran G, Wickham LD. The development of alternative storage sink sites in sweet potato Ipomoea batatas. Ann Bot. 1988;61:99–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soare JR, Dinis TCP, Cunha AP, Almeida L. Antioxidant activities of some extracts of Thymus zygis. Free Radic Res. 1997;26:469–478. doi: 10.3109/10715769709084484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Harish SR, Shivanandappa T. Antioxidant activity of the roots of Decalepis hamiltonii (Wight & Arn.) LWT Food Sci Technol. 2006;39:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2005.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Jagan Mohan Rao L, Shivanandappa T. Isolation of ellagic acid from the aqueous extract of the roots of Decalepis hamiltonii: antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effect. Food Chem. 2007;103:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Wealth of India (1990) A dictionary of indian raw materials & industrial products. Publications & Information Directorate, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, vol 1, p 161

- Umashankar K, Giridhar P. Biomass production and bioactive secondary metabolites of bioreactor grown callus suspension cultures of Swallow root (Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. J Emerg Technol Innov Res. 2022;9(3):g153–g158. [Google Scholar]

- Umashankar K, Pradeep M, Giridhar P. In vitro elicitation supports the enrichment of 2H4MB production in callus suspension cultures of D hamiltonii Wight & Arn. Romanian Biotechnol Lett. 2022;27(1):3302–3308. doi: 10.25083/rbl/27.1/3302-3308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ved D, Saha D, Ravikumar K, Haridasan K (2015) Decalepis hamiltonii. The IUCN Red list of threatened species of threatened species 2015: e.T50126587A50131330. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015- 2.RLTS.T50126587A50131330.en. Accessed 13 Nov 2020

- Wojtania A, Skrzypek E, Marasek-Ciolakowska A. Soluble sugar, starch and phenolic status during rooting of easy- and difficult-to-root magnolia cultivars. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2019;136:499–510. doi: 10.1007/s11240-018-01532-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Wu J, Luo Y, Bragg J, Anderson O, Vogel J, Gu YQ. Phylogenetic, molecular, and biochemical characterization of caffeic acid o-methyltransferase gene family in Brachypodium distachyon. Int J Plant Genomics. 2013;2013:423189. doi: 10.1155/2013/423189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xu L, Wang F, Deng M, Yi K. Modulating the root elongation by phosphate/nitrogen starvation in an OsGLU3 dependant way in rice. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:1144–1145. doi: 10.4161/psb.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]