Abstract

In Israel, 20% of wounds do not progress to full healing under treatment with conservative technologies of which 1 to 2% are eventually defined as chronic wounds. Chronic wounds are a complex health burden for patients and pose considerable therapeutic and budgetary burden on health systems. The causes of chronic wounds include systemic and local factors. Initial treatment involves the usual therapeutic means, but as healing does not progress, more advanced therapeutic technologies are used. Undoubtedly, advanced means, such as negative pressure systems, and advanced technologies, such as oxygen systems and micrografts, have vastly improved the treatment of chronic wounds. Our service specializes in treating ulcers and difficult-to-heal wounds while providing a multiprofessional medical response. Herein, we present our experience and protocols in treating chronic wounds using a variety of advanced dressings and technologies.

Keywords: chronic wounds, wound care, advanced dressings, advanced technologies

Introduction

The natural wound healing process can be described as the stepwise progression of stages beginning with homeostasis and moving through the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases. If healing of a wound stops at any stage of the process, the wound will not progress toward full healing. The failure to complete this process, despite medical therapy within 4 weeks after the initial insult is defined as a chronic wound. 1 Resulting from both endogenous and exogenous factors, chronic wounds can remain for weeks, months, and even years. Some of the more frequent endogenous factors include diabetes, hematologic diseases, immune diseases, and impaired blood circulation, while exogenous factors include severe trauma, pressure injury, and iatrogenic implants.

The healing process has been well researched, with identification of numerous beneficial factors, including oxygen tension, nutritional status, and external environment which act in various ways to support expedient wound resolution. 2 3 4 In the natural course of healing, a fine balance of these factors is necessary to achieve ultimate healing; however, through the course of ongoing research, numerous products have been designed to take advantage of these factors and promote a more optimal environment and support wound healing. 5 Herein, we present a brief overview of products used to support advancement of the healing process in chronic wounds at our institution.

Our Chronic Wound Service

The chronic wound service in the Rabin Medical Center provides advanced wound care services throughout the year, specializing in the treatment of pressure sores; vascular wounds; diabetic foot; traumatic wounds; and wounds secondary to radiation, chemotherapy, or autoimmune disease. Our multidisciplinary team includes specialist form infectious disease, radiology, podiatry, dietetics, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and nursing and also orthopaedic, vascular, and plastic surgeries. In 2020, more than 2,000 outpatients with chronic wounds were treated in the clinic and more than 1,000 additional wound consultations were given within the hospital setting.

Our skilled nursing staff is trained in the use of our dressings and technologies and places particular emphasis on minimizing the patient's pain, discomfort, and distress. Patients are also provided guidance with at-home wound care and the application of carious dressings to ensure a high standard of care.

Patient and Wound Evaluations and Standard Care

Treatment of chronic wounds always begins with a thorough patient assessment that evaluates for any medical comorbidities and other factors which may have contributed to failure of the healing process, including, nutrition status, medications, allergies, history of irradiation, and trauma to the wound area. Mechanism causing the insult, any treatment the patient already received, and whether a biopsy was performed when deciding on a course of treatment are of particular importance. Additionally, hematologic studies, serum chemistries, hemoglobin A1C, and nutritional parameters should be drawn to assess for any deficiencies. 6

Wound interventions have been developed to optimize the wound environment, reduce the burden of bacteria and nonviable tissue, and stimulate expression of growth factors. 7 At a minimum, management of chronic wounds involve local wound care and systemic measures. 8 To promote the healing processes, we often cleanse debride of the wound of any necrotic tissue, offload pressure to the affected area, and utilize dressings that promote a moist wound environment. Systemic treatment considerations often include the use of antibiotics to control infection and optimal nutritional supplementation.

Wound interventions have been developed to optimize the wound environment, reduce the burden of bacteria and nonviable tissue, and stimulate expression of growth factors. 7 To address these and other needs of chronic wounds, standard wound care is frequently employed alone or in combination with adjunctive wound treatments.

Treating a chronic wound can be time consuming and expensive. 9 It is essential to determine early in the treatment process if standard wound care alone is expected to be effective. 10 If a wound area decreases by more than 40% within 4 weeks, wound closure will likely occur with an additional 8 weeks of treatment. 11 This criterion, in combination with accurate measurement tools, is a helpful strategy to determine if standard wound care alone will be sufficient, or if an adjuvant therapy is indicated.

Dressings Used in the Management Chronic Wounds

Foam Dressings

The highly absorbent core of polyaniline/polyurethane foam wound dressings, like Biatain (Coloplast, Humlebaek, Denmark) and PolyMem (Ferris Mfg. Corp., Fort Worth, TX), promotes wound healing by reducing leakage. The dressings have demonstrated effectiveness in both wound healing and pressure sore prevention. 4 5 12 With their complex structure that engenders efficient thermal isolation and exudate retention, while their lack of an adhesive layer allows for easier removal, protects skin from trauma, and reduces pressure across the entire wound. 3

Alginate Dressings

Lamina seaweed or alginate dressings, such as Kaltostst (ConvaTec Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) and Silvercel (3M, St. Paul, MN), are nonwoven fabrics containing contains units of guluronate and mannuronate derived from the seaweed. These compounds form long chains that bind bivalent calcium ions. When applied to a wound, the calcium ions are exchanged for sodium ions in the exudate, forming a gelatinous matrix. 1 This process makes these dressings well suited for wounds with moderate-to-heavy exudate as they can absorb up to 20 times their weight in drainage and act as procoagulants. 6

Hydrocolloid Dressings

Aquacel and Aquacel Ag (ConvaTec Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) are hydrocolloid dressings, comprising a waterproof outer polyurethane film and a multilayered pad of polyurethane foam and hydrofiber. While the dressings are available with or without adhesive, the adhesive form is an effective choice for infected wounds, as its silicone border can be imbued with nano–silver ions which have been shown to have a broad antibacterial activity. 8

Collagen Dressings

Type-I collagen is a chemoattractant for inflammatory cells, thus promoting wound healing and epithelization. Containing collagen and cellulose, Promogran Prizma (3M, St. Paul, MN) and Fibra (3M, St. Paul, MN) work to absorb wound proteases leading to a reduction in overall wound size and increased likelihood of subsequent closure. 7

Enzymatic Debriding with Secondary Dressing

Enzymatic debriding agents, like Flaminal (Hydro/Forte; Flen Health, Konitch, Belgium), use an enzyme complex, containing glucose oxidase and lactoperoxidase, which protects against microbial colonization and reduces infection. As such, these agents may be used after careful wound assessment for bioburden control, creation of a moist environment, and promoting autolytic debridement. 9

Medical Honey Dressings

Medical honey dressings, like MediHoney (Integra LifeSciences, Princeton, NJ), provide an osmotic effect, facilitates debridement, and contain antimicrobial properties. In addition to its hydrogen peroxide–induced antioxidant effects, honey contains a broad spectrum of proteolytic enzymes capable of enhancing lymphocytic and phagocytic activity within the wound. 10

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), also termed as wound VACs, uses negative pressure to draw fluids away from the wound bed, reduces swelling, and facilitates cleaning the wound and removing bacteria from it. 11 The wound Vacuum-Assisted Closure (VAC) also facilitates approximation of the wound edges while stimulating growth in the new underlying tissue. Prior to securing the foam dressing of wound VAC, we ensure adequate debridement and hemostasis. A fenestrated tube is embedded in the foam dressing and the wound is sealed with an airtight adhesive tape. 12 The dressing is reopened every 3 to 4 days to view the extent of granulation tissue formation and to prevent periwound maceration.

Innovative Wound Healing Technologies

The Rigenera Technology

Rigenera (Human Brain Wave LLC, Turin, Italy) is a mechanical destructor of biological tissues, such as Derma, connective tissue, bone tissue, and dental pulp, that enables the obtainment of micrografts by autologous, homologous, and minimally invasive means ( Fig. 1 ). 13 The main apparatus consists of a grid with 100 hexagonal holes on the edges to which six microblades and an 80-μm filter are attached. Laboratory studies have shown that the cell population obtained after mechanical rupture is positive cell progenitor for mesenchymal markers with a viability above 90%. 14 15 This procedure entails minimally invasive microsurgery; we follow a standardized protocol performed in a single operation. 16

Fig. 1.

A standardized sample preparation system for the automated mechanical disaggregation of the cell population.

The first step involves obtaining viable micrografts via an autologous tissue biopsy. Once suitable tissue has been collected, it is loaded inside a disposable device with a sterile physiological solution and processed through the device where it is disaggregated over the course of one minute. 17 The prepared micrografts are harvested and injected directly onto the area to be treated, with or without the addition of a collagen scaffold before final closure of the wound. The procedure does not require special preparations for the patient nor a period of convalescence or rehabilitation, except for the removal of stiches from the donor site which occurs 10 to 15 days after treatment. 18

While this process is very similar to skin grafting, its key benefit is deceased risk to the donor site. Additionally, the donor site harvested from the patient is only 5% the size of the area to be treat compared with skin grafting in which viable tissue must be harvested in a 1:1 ratio with the wound. 16

Rigenera can be used for defects of all kinds of tissue, including skin, fat, cartilage, and bone, and it has a wide variety of applications such as chronic wounds and burns. With its single application protocol, we are able to harvest, process, and place the graft in a single visit, thereby reducing the risk of cross-contamination of tissues, graft rejection, and further trips to the operating room. 19 In our clinical experience, when used on patients with chronic wounds, Rigenera was able to facilitate healing in approximately 8 weeks ( Fig. 2 ). 20

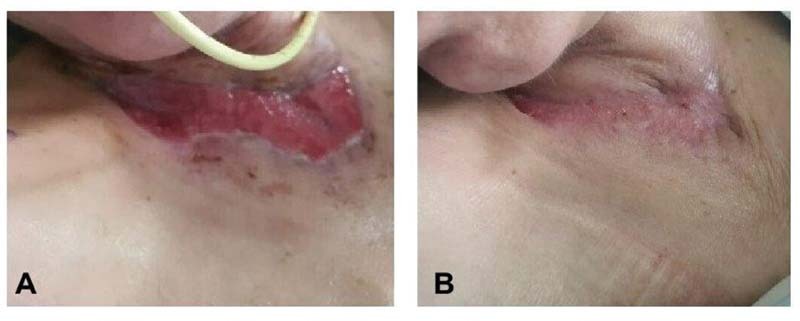

Fig. 2.

Rigenera technology: the injection of micrograft to a patient with a neck burn who was not scheduled for surgery due to a complex medical condition. ( A ) Before treatment, ( B ) 1 month following treatment.

The E-QURE BST Device

Under normal circumstances, a healing wound emits a measurable electric field, a phenomenon which is absent in many chronic wounds. 21 While electrostimulation devices are not necessarily novel in and of themselves, the E-QURE BST goes beyond the biostimulation offered by other devise, mimicking the resonant frequencies associated with actively healing wounds, thus facilitating the natural healing process ( Fig. 3 ). 22 A typical treatment regimen consists of three 30-minute stimulation sessions which can be done at home by patients themselves or by their caregivers. 23 The E-QURE BST device is intended as an adjunct to standard of care treatment for home patients with chronic ulcers who have not demonstrated measurable signs of improved healing for at least 30 days. The E-QURE BST device, we used, consists of an electrical signal generator whose output is connected to a pair of disposable adhesive electrodes. These electrodes are affixed to the healthy skin adjacent to an ulcer, with one electrode on each side and an electrical current passed through them to stimulate healing. Each pair of electrodes is used until the wound dressing is changed or for up to 72 hours. The amount of electrical stimulation may be highly variable. Various applications and modalities of electrical stimulation are available, including direct current, high-voltage pulsed current, alternating current, and low-intensity direct current. Direct current is known to cause directional migration of various types of cells, such as lymphocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, and keratinocytes, which enhances reepithelialization ( Fig. 4 ). 11 21 24 25 26 27 28 Other currents, such as alternating current, have been reported to activate cutaneous sensory nerves, and thus to increase blood flow and sensation around wounds. Despite variations in the type of current, the majority of studies investigating the use of electrical stimulation have demonstrated significant improvements in wound area reduction or accelerated wound healing, compared with standard wound care or sham therapy. 29

Fig. 3.

E-QURE BST device: a computerized controlled single-channel bioelectrical stimulator.

Fig. 4.

E-QURE BST technology: ( A ) a 6-month chronic injury, ( B ) 18 months post biopsy without any conventional dressing.

Furthermore, electric field therapy has been shown to activates the production of ATP and DNA; this causes fibroblasts to generate more collagen and to increase blood flow and capillary density. 30 31 32 When standard wound care alone fails to heal chronic wounds, the addition of electrical stimulation can improve healing and closure as has been shown in several clinical trials. 28 29 33 34 35 36

The NATROX Oxygen Wound Therapy System

Physiologic Role of Oxygen in Wound Healing

Oxygen plays a vital role in wound healing processes. Reports have demonstrated that roughly 20 mm Hg of oxygen is needed to promote healing which is well above the oxygen tension measured in some wounds. 37 The increased energy demands of healing tissue leads to a hypermetabolic state, increasing the oxygen demand of the healing tissue. 38 In anoxic environments, cells convert to anaerobic metabolism hindering wound healing activities, such as cell division, and, ultimately, collagen production and reepithelialization. 37 39 If low oxygen states are sustained, cell death and tissue necrosis eventually ensue, due to the inability of the cells to repair the spontaneous decay of cell components and to maintain calcium pumps. 39

Conversely, states of higher oxygen tension have been shown to increase the rate of wound closure, promote fibroblast proliferation and protein production, reverse the low number of endothelial progenitor cells in diabetics, and increase collagen production. Given the myriad of roles oxygen plays in wound healing, it is essential to ensure adequate tissue oxygenation for enhanced wound healing.

The Natrox oxygen wound therapy system enhances the normal wound healing process by making use of the body's natural reliance on oxygen for the facilitation of intracellular processes and overall cell survival. The system includes both oxygen generator powered by a small rechargeable battery and oxygen concentrator connected with a fine, soft tube to a specially designed delivery system which can be placed over a wound ( Fig. 5 ). The device generates oxygen through the electrolysis of water that is naturally present in the atmosphere. The energy produced by the battery creates a positive charge on one face of the membrane inside the oxygen generator and a negative charge on the other side. This charge then splits the hydrogen and oxygen that composes water, pulling the positive hydrogen ions one way and the negative oxygen ions the other. The hydrogen ions then recombine with oxygen molecules from the air to form more water which then splits again across the membrane. The oxygen ions combine in pairs to form oxygen molecules that accumulate and then start to flow down the tubing to the oxygen delivery system. The 98% oxygen that is generated is delivered at a rate of approximately 15 mL/h.

Fig. 5.

NATROX technology: a battery-operated device that delivers continuous pure humidified oxygen to the wound bed through water electrolysis.

The Natrox system allows the oxygen to diffuse evenly and continuously over the wound surface while the compact design of the device gives it flexibility in applications. Its size makes it suitable to wear under clothing during daily activities and can be positioned comfortably for use at night. Overall, compared with other topical oxygen treatments, this system is more easily tolerated by our patients ( Fig. 6 ).

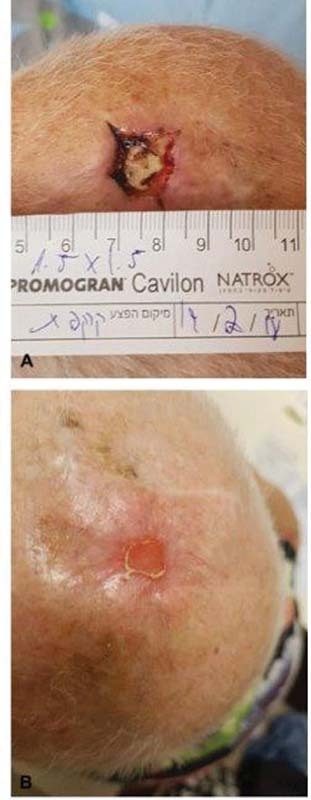

Fig. 6.

NATROX technology: ( A ) a scalp wound following tissue removal, without the ability to use flaps, ( B ) 3 months following treatment.

ActiGraft

Blood-derived products, such as platelet-rich fibrin, platelet-rich plasma, fibrin glue, macrophages, and various growth factors, have gained widespread use in the treatment of chronic wounds ( Fig. 7 ). In response to injury, a fibrin scaffold that serves as a protective, provisional extracellular matrix (ECM) to aid in the formation of a blood clot which harbors cytokines and growth factors released by the degranulation of activated platelets. 40 41 As the clot dries out, it becomes a protective scab, under which a moist wound environment can be maintained and tissue remodeling takes place. 42

Fig. 7.

ActiGraft technology: the fibrin matrix derived from the patient's own blood.

Developed for use at point of care to protect open wounds and to facilitate the healing process, AntiGraft RD1 (RedDress Ltd., Pardes-Hanna, Israel) is a provisional autologous whole blood product capable of providing a functional ECM ( Fig. 8 ). Easily prepared at bedside using a small amount of the patient's whole blood, ActiGraft does not undergo the manipulation, separation, or augmentation seen with other blood products. Instead by mixing the blood with kaolin, natural clot formation is accelerated, allowing for a safe, rapid alternative means of accessing all the benefits of a natural clot. Once mixed, the resulting gel can be applied topically to a variety of wounds, including ulcers and mechanically and surgically debrided wounds.

Fig. 8.

ActiGraft: ( A and B ) a traumatic wound with exposed bone, ( C ) 1 month after four rounds of ActiGraft therapy.

Matriderm

The MatriDerm (Dr. Suwelack Skin & Health Care AG, Billerbeck, Germany) three-dimensional matrix dressing is an acellular tissue substitute composed of structurally intact collagen fibrils and elastin used to provide a new ECM scaffold, support dermal regeneration, integrate cells and blood vessels, and modulate the formation of scar formation ( Fig. 9 ). Obtained by harvesting type-I, -III, and -V collagens from bovine dermal cells and hydrolyzing bovine nuchal ligament to collect elastin, MatriDerm is used together with split-thickness skin grafts (STSG) in the surgical repair of burns, trauma, and dermatological diseases and also in full-thickness skin wounds. 43 44 It can also be used in the treatment of other poorly healing wounds that require the addition of a skin graft. This dressing has been shown to yield the best results when it used in combination with a wound VAC system for a period of about 1 week. 44

Fig. 9.

Matriderm technology: a collagen-elastin scaffold.

When applied over a wound, MatriDerm acts as a neodermis and improves the quality of reconstituted skin, reduce scarring, prevent wound contraction, and restore functionality. MatriDerm can also be used under intact skin for the temporary separation of tissues, preventing the formation of unstructured scar tissue that can lead to adherence of tendons and their surrounding connective tissue, following injuries or surgical procedures ( Fig. 10 ). 45

Fig. 10.

Matriderm technology: ( A ) a traumatic necrotic orthopedic wound, ( B ) which underwent debridement, ( C ) vacuum-assisted closure, and then closure with Matriderm and ( D ) development of well-granulated wound. ( E ) Wound coverage with split thickness skin graft. ( F ) Successful resolution of the wound.

The thin profile of the dressing supports diffusion of a steady initial supply of nutrients throughout the graft, rapid vascularization then follows. As healing progresses, fibroblast produce their own collagen matrix. After surgery, adherence between various layers of the tissue can develop due to unstructured scar formation during the healing process. 46 The movement of tissues against each other remains possible even after healing, preventing impairment caused by restricted mobility or pain.

Clinical trials on the treatment of reconstructive wounds and burns have shown substantial improvement in elasticity of regenerated skin after 3 to 4 months, with the combined use of MatriDerm and STSG than with the latter alone. 43 47 Long-term follow-up revealed improved elasticity 12 years after surgery in the regenerated skin of patients treated with MatriDerm. 43 47

Conclusion

The etiology of chronic wounds is associated with both endogenous and exogenous factors. The increasing awareness among providers about the development of chronic wounds, as well as adjunctive wound care modalities, opens vast potential for chronic wound prevention and treatment. Advanced technologies, as well as dressings has progressed dramatically for the treatment of chronic wounds that do not respond to standard treatment. Multidisciplinary clinics are particularly suitable for treating chronic wounds. Further research on the use of advanced technologies is needed to characterize the optimal technology for each patient.

Conflicts of Interest None declared.

These authors contributed equally to the work.

References

- 1.Hawthorne B, Simmons J K, Stuart B, Tung R, Zamierowski D S, Mellott A J. Enhancing wound healing dressing development through interdisciplinary collaboration. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2021;109(12):1967–1985. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruberg R L. Role of nutrition in wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64(04):705–714. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)43386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pahlevanneshan Z, Deypour M, Kefayat A. Polyurethane-nanolignin composite foam coated with propolis as a platform for wound dressing: synthesis and characterization. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13(18):3191. doi: 10.3390/polym13183191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pyun D G, Yoon H S, Chung H Y. Evaluation of AgHAP-containing polyurethane foam dressing for wound healing: synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med. 2015;3(39):7752–7763. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00995b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng Y, Zhao H, Yin Z, Qi X. IOT medical device-assisted foam dressing in the prevention of pressure sore during operation. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2021;2021:5.570533E6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otari S V, Jadhav J P. Singapore: Springer; 2021. Seaweed-based biodegradable biopolymers, composite, and blends with applications; pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhry S A, Nieves-Malloure Y, Camardo M, Robertson J M, Keys J. Use of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen dressings versus standard of care over multiple wound types: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2022;19(02):241–252. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song S, Liu Z, Abubaker M A. Antibacterial polyvinyl alcohol/bacterial cellulose/nano-silver hydrogels that effectively promote wound healing. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;126:112171. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbu A, Neamtu B, Zăhan M, Iancu G M, Bacila C, Mireșan V. Current trends in advanced alginate-based wound dressings for chronic wounds. J Pers Med. 2021;11(09):890. doi: 10.3390/jpm11090890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghorbani M, Ramezani S, Rashidi M R. Fabrication of honey-loaded ethylcellulose/gum tragacanth nanofibers as an effective antibacterial wound dressing. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2021;621:126615. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar B A, Sundresh N. Role of vacuum-assisted closure in wound healing. International Journal of Recent Advances in Multidisciplinary Topics. 2021;2(12):84–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Normandin S, Safran T, Winocour S. Negative pressure wound therapy: mechanism of action and clinical applications. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;35(03):164–170. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trovato L, Monti M, Del Fante C. A new medical device rigeneracons allows to obtain viable micro-grafts from mechanical disaggregation of human tissues. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(10):2299–2303. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko M S, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(05):585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(03):835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma R R, Pollock K, Hubel A, McKenna D. Mesenchymal stem or stromal cells: a review of clinical applications and manufacturing practices. Transfusion. 2014;54(05):1418–1437. doi: 10.1111/trf.12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zahorec P, Koller J, Danisovic L, Bohac M. Mesenchymal stem cells for chronic wounds therapy. Cell Tissue Bank. 2015;16(01):19–26. doi: 10.1007/s10561-014-9440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trovato L, Failla G.Regenerative surgery in the management of the leg ulcersJ Cell Sci Ther 2016;07(02):

- 19.De Francesco F, Graziano A, Trovato L. A regenerative approach with dermal micrografts in the treatment of chronic ulcers. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2017;13(01):139–148. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graziano A, Carinci F, Scolaro S, D'Aquino R. Periodontal tissue generation using autologous dental ligament micro-grafts: case report with 6 months follow-up. Ann Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;1(02):20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M. Electrical fields in wound healing-an overriding signal that directs cell migration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(06):674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCaig C D, Rajnicek A M, Song B, Zhao M. Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(03):943–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feedar J A, Kloth L C, Gentzkow G D. Chronic dermal ulcer healing enhanced with monophasic pulsed electrical stimulation. Phys Ther. 1991;71(09):639–649. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.9.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura K Y, Isseroff R R, Nuccitelli R.Human keratinocytes migrate to the negative pole in direct current electric fields comparable to those measured in mammalian wounds J Cell Sci 1996109(Pt 1):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin F, Baldessari F, Gyenge C C. Lymphocyte electrotaxis in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181(04):2465–2471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimoto M, Maeshige N, Honda H.Optimum microcurrent stimulation intensity for galvanotaxis in human fibroblasts J Wound Care 201221015–6., 8, 10, discussion 10–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orida N, Feldman J D. Directional protrusive pseudopodial activity and motility in macrophages induced by extracellular electric fields. Cell Motil. 1982;2(03):243–255. doi: 10.1002/cm.970020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraccalvieri M, Salomone M, Zingarelli E M, Rivarossa F, Bruschi S. Electrical stimulation for difficult wounds: only an alternative procedure? Int Wound J. 2015;12(06):669–673. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kloth L C. Electrical stimulation for wound healing: a review of evidence from in vitro studies, animal experiments, and clinical trials. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005;4(01):23–44. doi: 10.1177/1534734605275733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampe K E. Electrotherapy in tissue repair. J Hand Ther. 1998;11(02):131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(98)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourguignon G J, Bourguignon L YW. Electric stimulation of protein and DNA synthesis in human fibroblasts. FASEB J. 1987;1(05):398–402. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.1.5.3678699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borba G C, Hochman B, Liebano R E, Enokihara M MSS, Ferreira L M. Does preoperative electrical stimulation of the skin alter the healing process? J Surg Res. 2011;166(02):324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kloth L C, Feedar J A. Acceleration of wound healing with high voltage, monophasic, pulsed current. Phys Ther. 1988;68(04):503–508. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jünger M, Arnold A, Zuder D, Stahl H W, Heising S. Local therapy and treatment costs of chronic, venous leg ulcers with electrical stimulation (Dermapulse): a prospective, placebo controlled, double blind trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(04):480–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DDCT Group . Adunsky A, Ohry A. Decubitus direct current treatment (DDCT) of pressure ulcers: results of a randomized double-blinded placebo controlled study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(03):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricci E, Afaragan M. The effect of stochastic electrical noise on hard-to-heal wounds. J Wound Care. 2010;19(03):96–103. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.3.47278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaVan F B, Hunt T K. Oxygen and wound healing. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17(03):463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen D B, Maguire J J, Mahdavian M. Wound hypoxia and acidosis limit neutrophil bacterial killing mechanisms. Arch Surg. 1997;132(09):991–996. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330057009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milton S L, Prentice H M. Beyond anoxia: the physiology of metabolic downregulation and recovery in the anoxia-tolerant turtle. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;147(02):277–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates S M, Weitz J I. Coagulation assays. Circulation. 2005;112(04):e53–e60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.478222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You H J, Han S K. Cell therapy for wound healing. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(03):311–319. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo S, Dipietro L A. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89(03):219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haslik W, Kamolz L P, Nathschläger G, Andel H, Meissl G, Frey M. First experiences with the collagen-elastin matrix Matriderm as a dermal substitute in severe burn injuries of the hand. Burns. 2007;33(03):364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haslik W, Kamolz L P, Manna F, Hladik M, Rath T, Frey M. Management of full-thickness skin defects in the hand and wrist region: first long-term experiences with the dermal matrix Matriderm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(02):360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cervelli V, Brinci L, Spallone D. The use of MatriDerm and skin grafting in post-traumatic wounds. Int Wound J. 2011;8(04):400–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maitz J, Wang Y, Fathi A. The effects of cross-linking a collagen-elastin dermal template on scaffold bio-stability and degradation. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020;14(09):1189–1200. doi: 10.1002/term.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryssel H, Gazyakan E, Germann G, Öhlbauer M. The use of MatriDerm in early excision and simultaneous autologous skin grafting in burns–a pilot study. Burns. 2008;34(01):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]