Abstract

Liver plays a major role in many inherited and acquired genetic disorders. It is also the site for the treatment of certain inborn errors of metabolism that do not directly cause injury to the liver. The advancement of nucleic acid-based therapies for liver maladies has been severely limited due to the myriad of untoward side effects and methodological limitations. To address these issues, research efforts in recent years have been intensified towards the development of targeted gene approaches using novel genetic tools, such as the zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs), as well as various non-viral vectors, such as Sleeping Beauty transposons, piggyBac transposons and PhiC31 integrase. While each of these methods utilizes a distinct mechanism of gene modification, all of them are dependent upon the efficient delivery of DNA and RNA molecules into the cell. This review will provide an overview on current and emerging therapeutic strategies for liver-directed gene therapy and gene repair.

Keywords: Gene therapy, Liver, Viral vectors, Non-viral vectors, Gene replacement

INTRODUCTION

Liver-directed gene therapy (LDGT) can be used to treat a number of inherited metabolic and acquired disorders (Table 1). In addition to acute and chronic liver failure, hepatic transplantation can correct a variety of inborn errors of metabolism, such as familial amyloidosis, hereditary oxalosis, α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, Wilson’s disease, tyrosinemia, type I and IV glycogen storage diseases, Niemann-Pick disease, Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CN1), urea cycle enzyme deficiencies, C protein deficiency, and hemophilias A and B. Treatment of inherited disorders presents a special opportunity for the application of LDGT since single gene abnormalities underlie many inherited disorders. In fact, the effect of gene therapy can be evaluated directly and precisely in these conditions, and in many situations quickly.

TABLE 1.

A Partial List of Liver-related Diseases that could Benefit from Gene Therapy

| I. Inherited liver disorders |

| Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 |

| Familial hypercholesterolemia and other lipid metabolic disorders |

| Maple syrup urine disease |

| Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis |

| Phenylketonuria |

| Tyrosinemia |

| Mucopolysaccharidosis VII |

| α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency |

| Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency |

| Wilson’s disease |

| Glycogen storage diseases, e.g. von Gierke’s disease and Pompe’s disease |

| Hyperbilirubinema |

| Acute intermittent porphyria |

| Citrullinemia type 1 |

| II. Inherited systemic disorders |

| Hemophilia A and B |

| Oxalosis |

| III. Acquired disorders |

| Infectious diseases, e.g. Hepatitis B and C |

| Malignant neoplasms: Hepatomas, cholangiocarcinomas, metastatic tumors |

| Extrahepatic tumors (inhibition of neovascularization) |

| Cirrhosis of the liver |

| Allograft or xenograft rejection |

In the past, LDGT was successfully used to generate pharmacological gene products for specific therapeutic purposes and to inhibit the expression of harmful proteins by transferring synthetic antisense RNAs, genes that express antisense RNAs, ribozymes or dominant-negative proteins (1, 2). In contrast, neoplastic diseases were found to be challenging targets for LDGT because they require approaches that selectively eliminate tumor cells while sparing non-tumor cells. It has been shown that cancer cells can also be killed by transferring “suicide genes” such as the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) (3), cytosine deaminase (4), purine nucleoside phosphorylase (5), and the apoptosis-inducing tumor suppressor p53 (6). Gene transfer to all cells in a given tumor remains a challenge, and so is the need to prevent the toxic exchange between tumor cells and neighboring non-tumor cells (so called, bystander effect). This is particularly demonstrated by a tumor cell undergoing p53-induced apoptosis that delivers a “kiss of death” to neighboring cells (7). Therefore, efforts were directed towards inducing immune responses against tumor cells but they were mostly unsuccessful.

Immunotherapy leverages the expression of antigens specific to tumor cells that are not expressed in normal adult cells to evoke an immune response (8). Molecular identification, isolation, and genetic manipulation of tumor-specific antigens were thought to facilitate the development of gene transfer-based tumor vaccination and permit the induction of an immune response against tumor cells. Even though a method involving the inhibition of tumor neovascularization, such as by increasing the expression of angiostatin or endostatin (9, 10), was met with some success it may not be appropriate for all cancers. Among the other problems that hampered progress were intrinsic toxicity of viral proteins, host immune responses against viral vectors and transgene products, and efficient delivery of viral and non-viral vectors to the target site (11). These problems have led researchers to develop alternative gene therapy strategies, and as a result, the past decade has witnessed an advent of many innovative approaches. Here, we present an overview of LDGT strategies that have been attempted, and discuss exciting new developments that are very promising.

Ex vivo gene therapy directed at autologous stem cells or human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) followed by directed differentiation and transplantation provides a promising approach for treating both inherited metabolic and acquired disorders (12). Specifically, stem cells or somatic cells can be collected from specimens of patients, and somatic cells can then be reprogrammed into iPSCs by the introduction of a particular set of transcription factors. IPSCs thus generated are capable of differentiating into cells from all three germ layers including hepatocytes and endothelial cells. The transgene of interest can subsequently be introduced into liver stem cells or iPSCs either by viral transduction or transfection with non-viral plasmid vectors. Alternatively, the gene of interest can be altered by targeted gene modification (see below for a discussion). In the future, once relevant safety concerns (including the stability of the mature liver-like phenotype) and technical issues for the transplantation procedure are solved, hepatocyte-like cells from genetically corrected stem cells or iPSCs could be an option for autologous transplantation in liver diseases (13, 14).

VIRAL VECTORS

The suitability of a recombinant virus for LDGT is based on several factors including, the infectious titer that can be achieved, ability of the virus to infect non-dividing cells, efficiency of integration into the host genome, repeatability of administration, limited immune responses to the virus and the transgene, and safety of the vector system. Even though none of the currently available viral vectors satisfy all these criteria, there are a relatively large number of options for specific applications. At present, there are four significant barriers to successful viral gene therapy. These include (i) uptake, transport, and uncoating of the virus; (ii) vector genome persistence; (iii) transcriptional persistence; and (iv) the immune response (Figure 1). To date, LDGT using a wide variety of viral vectors to deliver genes of interest has met with mixed success. Gene transfer is commonly achieved with replication-deficient recombinant viruses that express desired transgenes without expressing viral proteins.

Figure 1.

Major barriers to successful viral gene therapy. (A) Uptake, transport and uncoating. Vectors bind to a cellular membrane and are internalized by various processes. Most uptake steps involve a ligand-receptor interaction. Once internalized, the majority of vectors enter the endosome and undergo a complex set of reactions that can result in their full or partial degradation. Viruses have evolved effective mechanisms for escaping from the endosome; for example, adenoviruses lyse the endosome. Transport to the nucleus is also required for successful therapy. (B) Vector genome persistence. Once the vector reaches the nucleus, it can be further processed. Depending on the vector, the DNA can exist as an episomal molecule (and associate with the nuclear matrix) or it can be integrated (by covalent attachment) into the host chromosome. (C) Transcriptional activity and transgene persistence are dependent on many factors including epigenetic changes to the transgene. (D) The immune response can limit the viability of the transduced cells and/or the expression of the transgene product. CTL, cytotoxic T cell lymphocyte; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; and TCR, T cell receptor. (Reproduced from reference 20, with permission)

Retroviral Vectors

Retroviruses are among the most widely used viral vectors in gene therapy. They produce faithful transmission of the transgene into the transduced cell progeny by integrating their complementary DNA into the host genome during their life-cycle (15, 16). Typically, the RNA genome of retroviruses encodes major viral proteins: gag, pol and env; whereas the long terminal repeats (LTRs) consisting of signals needed for viral transcription are found at the 5’ and 3’ ends of the coding region. Packaging sequences required for the incorporation of viral RNA genome into viral particles are located upstream of the 5’ LTR. Retroviruses enter mammalian cells through specific cell surface receptors, which limit their range of infectivity. However, the host range can be expanded and the stability of the virus may be substantially increased through the modifications of viral envelope that can serve to redirect receptor interactions. After entry into mammalian cells, the RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into double-stranded DNA provirus, which is incorporated into a pre-integration nucleoprotein complex (PIC). The PIC must be transferred into the nucleus for integration of the provirus into the host genome. The PIC of viruses, such as the Moloney’s murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV) does not pass through intact nuclear membranes. Therefore, mitosis-associated dissolution of nuclear envelope is required for the integration of the MoMuLV provirus (17, 18). This limits the efficiency of these viruses in transferring genes into hepatocytes, which are normally quiescent in vivo. Interestingly, however, long-term correction of hemophilia A using retroviral vectors expressing human factor VIII was reported in newborn, factor VIII-deficient mice (19).

Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviral vectors are retroviral vectors derived from human immunodeficiency virus that can transduce non-dividing cells and possess an LTR that lacks a robust enhancer (20). However, two major concerns with retroviral vectors in gene therapy include the risk of insertional mutagenesis and immune responses directed against transgenes (21). Therefore, replication-defective retroviruses were developed by replacing most or all viral genes by target transgenes (22). To generate these recombinants, a plasmid vector is transfected into “packaging cell lines” that provides the required viral proteins in trans. As most of the viral coding sequences are deleted, the recombinant retrovirus can accommodate relatively large exogenous DNA segments. It has been shown that hepatocyte-targeted expression using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors cause sustained induction of immune tolerance to the transgene, albeit with reduced transgene expression levels in comparison with their integrase-competent vector counterparts (23). In another study, integrase-defective lentiviral vector-mediated coagulation factor IX expression targeted to hepatocytes prevented the induction of neutralizing antibodies to the protein even after antigen re-challenge in hemophilia B mice, and resulted in relatively prolonged (~ 52 weeks) therapeutic factor IX expression levels (23). These vectors also induced transgene-specific regulatory T cells that contributed to the observed immune tolerance. Thus, integrase-defective lentiviral vectors provide an attractive platform for the tolerogenic expression of intracellular or secreted proteins in the liver with a substantially reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis.

Immune tolerance to a lentiviral transgene has also been achieved by targeting transgene expression specifically to the liver and including hematopoietic-specific microRNA-142 downstream from the transgene to suppress any residual expression of the transgene in antigen-presenting cells (24, 25). The approach was quite novel and confirmed the potential of gene therapy using microRNAs. In addition, based on encouraging results from pre-clinical trials with lentiviral vectors in treating hemophilia A using genetically engineered hematopoietic stem cells, a clinical trial has recently been approved by the US FDA (26). It is anticipated that the lentiviral gene therapy for FVIII deficiency may be nearing clinical approval.

Recombinant Adeno-associated Virus (AAV)

An adeno-associated virus is a replication-defective, non-enveloped virus that does not cause disease, and only induces a very mild immune response. In the liver, AAV-induced immune response can easily be blunted by inhibiting the expression of Toll-like receptor 9 (27). One major advantage of AAV vectors is the finding that they can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells with high efficiency. The AAV genome is comprised of three promoters (p5, p19, and p40), a polyadenylation signal, a non-structural gene (Rep) and the structural Cap gene (28), of which the Rep protein directs the specificity of AAV integration into chromosome 19 as a head-to-tail concatamer. Approximately 96% of the viral genes can be replaced with foreign DNA and packaged into an AAV virion that does not possess a dominant enhancer/promoter activity.

To date, there are eleven known serotypes of human AAV (28). AAV2 and AAV8 are the most commonly used vectors for gene therapy because of their higher rates of transduction efficiency when compared to AAV5 which transduces poorly in the liver, as shown recently in rat models of CN1 and hyperbilirubinema (29). Moreover, gene transfer efficiency of AAV vectors is comparable to that of Ad vectors, at least in the rat liver (30). AAV is a small (4.7 kb) single-stranded DNA parvovirus that preferentially integrates into the q13.4-ter arm of human chromosome 19 (31). Recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors can be generated by co-transfecting two plasmids, one containing the transgene flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and the other encoding Rep, Cap and adenoviral proteins, into packaging 293 cells (Figure 2). rAAV sequences are then rescued from the integration site with a helper virus or plasmid, which ultimately results in productive lytic infection (32, 33). When a helper virus is not present, latent infection results in prolonged integration of the viral genome into the host genome. However, treatment of cells with a variety of genotoxic stimuli and irradiation could also cause AAV to replicate in host cells (33–35). Even though the ability to re-administer rAAV vectors is limited by host humoral and cellular immune responses, repeated administration may be possible through the pseudotyped rAAV containing capsids of alternative serotypes. Efforts are underway to generate AAV vectors containing capsids with desired characteristics by mutagenesis of the Cap gene because various AAV serotypes have distinct tissue tropisms related to their capsids.

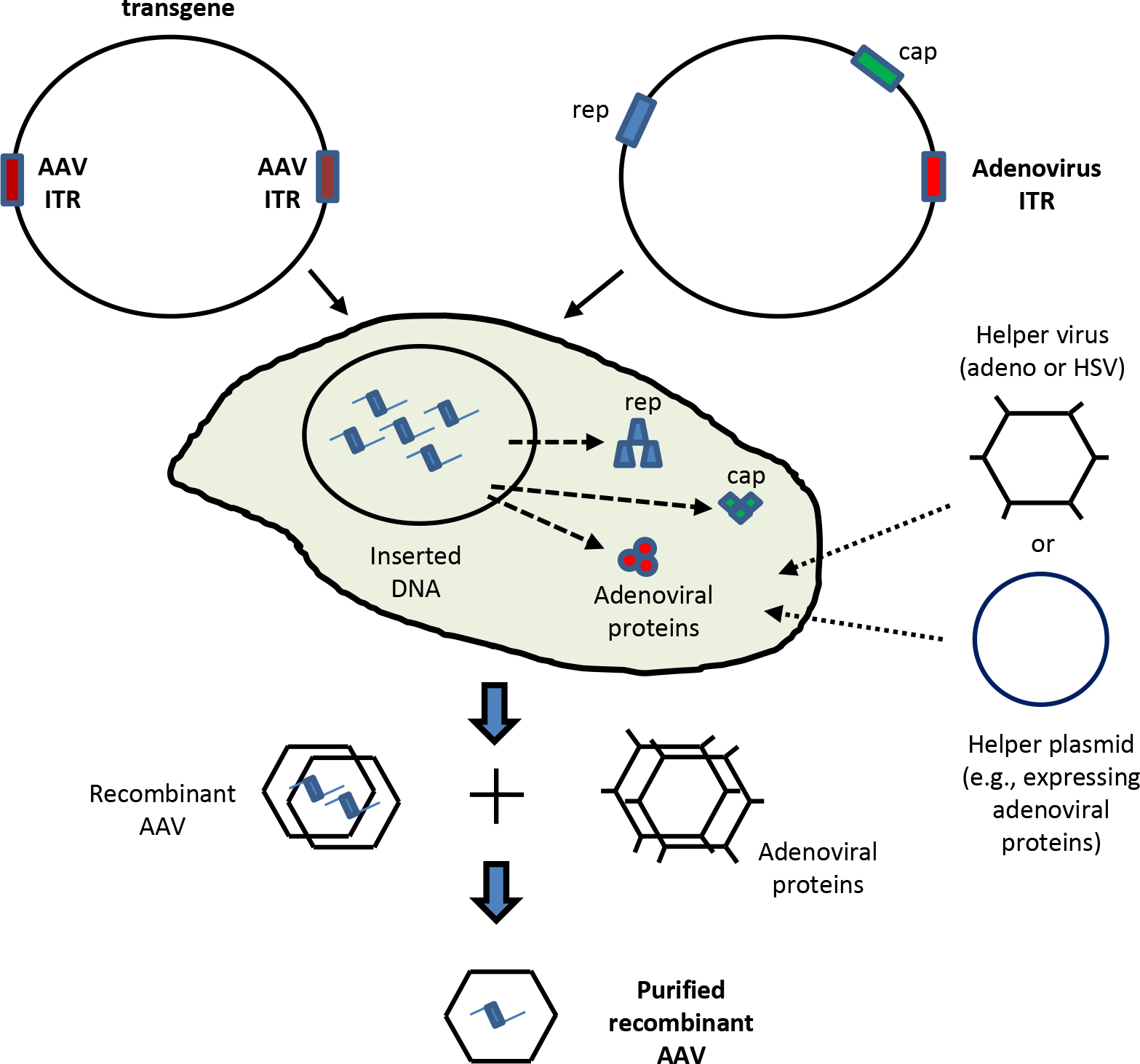

Figure 2.

Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV). Two plasmids, one containing the transgene, flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and another encoding the helper proteins, rep and cap proteins are transfected into 293 packaging cells. AAV is generated by infecting the transfected cells with a helper virus (such as, E1A-deleted adenovirus) or by transfecting a plasmid expressing the critical adenoviral protein. If a helper virus is used, the recombinant AAV is purified subsequently from the helper adenovirus.

rAAV vectors have been shown to persist for up to one year in hepatocytes as episomes and are eventually lost (36). Peripheral-vein infusion of an AAV vector expressing human factor IX (FIX) into six patients with severe hemophilia B (< 1% normal FIX levels) was demonstrated to result in stable (> 36 months) FIX transgene expression at levels 1–6% of normal levels, which was sufficient to improve the bleeding phenotype (37). However, immune-mediated clearance of AAV-transduced hepatocytes remains a concern, which may be controlled with a brief course of glucocorticoids. More recently, it was shown that gene therapy for hemophilia B can be improved by expressing a 16 bp RBE sequence of AAV together with the Rep protein (38), and intramuscular injection of AAV8 vectors resulted in enhanced hepatic targeting and transgene expression in mice and macaques (39). Also, rAAV3 vectors were shown to reduce tumorigenesis in human liver cancer cells in vitro and in a mouse xenograft model of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (40).

Because of their excellent safety profile, rAAV vectors are being used widely in clinical trials (26, 41, 42) even though their preclinical outcomes are not always predictable in humans (43–45). To understand this problem, a study has been conducted using different variants of clinically relevant rAAV vectors in a human-mouse chimeric liver model (46). It was shown that, when compared with rAAV2 vectors, rAAV8 vectors transduced 20 times less efficiently than in murine hepatocytes. In comparison, one chimeric capsid carrying five different parental AAV capsids transduced with high efficiency both in vivo and in vitro in primary human hepatocytes, and in a HCC xenograft model (46). In the light of these findings, it is clear that the selection and evaluation of rAAV serotypes in animals needs improvement prior to their use in human clinical trials. Despite these issues, clinical trials in humans are being carried out using rAAV vectors for a number of liver diseases (42).

The use of rAAV vectors has been demonstrated recently to inhibit microRNAs (miRNAs) and liver-specific genes as well. In one study, specific and long-term inhibition of miRNAs was achieved by expressing ‘tough decoys’ from rAAV9 vectors to study gene therapy for diseases, such as dyslipidemia, caused by miRNA deregulation (47). Another study accomplished sustained expression of synthetic miRNAs from rAAV9 vectors to continuously inhibit expression of the mutant AAT protein in the liver as a means of overcoming AAT deficiency (48). In it, a dual-therapy approach was adopted where the inhibition of mutant AAT was coupled with the induced expression of wild-type AAT, also from a rAAV9 vector. Such alternative gene therapy methods that target multiple genes, either to inhibit or regulate their expression, are appropriate for diseases such as HCC where the expression of a number of genes is dysregulated.

Recombinant Simian Virus 40 (SV40)

SV40 virus is a non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus with a 5.2 kb circular genome. It expresses two immunogenic viral antigens (large (Tag) and small (tag) T antigens) and structural genes, VP1, VP2, VP3. Their expression is achieved by differential splicing of a single RNA transcript (49). Among them, Tag confers an immortalizing effect on the cell and is widely used as an agent to generate immortalized cell lines. To generate a recombinant SV40 (rSV40) virus, the Tag gene is usually replaced by a target transgene. Viral particles are generated by transfecting the recombinant genome into COS-7 cells, which provide the Tag in trans. In the absence of the Tag gene, the recombinant virus cannot replicate and has significantly reduced immunogenicity (49).

SV40 gene therapy vectors have broad specificity, can be produced in high titers and have high transduction efficiency (50). In addition, the ability of these vectors to infect non-dividing cells makes them attractive for LDGT. However, the SV40 is a small virus, and therefore, the capacity of SV40 to accommodate exogenous DNA is limited to 4.7 kb, which could potentially be a major drawback. In mouse livers transduced in vivo, transgene expression was found to be at comparable levels both in the regenerated and pre-operative livers, suggesting that replication-incompetent SV40 vectors (rSV40) persist in vivo despite extensive cell division (51). Moreover, they can be easily administered for liver targeting. When injected into the tail-veins of mice, rSV40 vectors were able to reach the liver and express the luciferase transgene within a few days (52). These results indicate that rSV40 vectors are highly suitable for LDGT.

Recombinant Adenovirus

Adenoviruses are non-enveloped linear double-stranded DNA viruses that can infect both dividing and quiescent cells (53, 54); and they can be produced at high titers. For gene transfer purposes, recombinant adenoviral (rAd) vectors are normally generated using the serotypes 2 and 5. rAd vectors are produced by cloning the transgene of interest into the E1 domain of the virus. Additional adenoviral genes, e.g. E3 and E4, may also be deleted to increase the cloning capacity of the vector. Similar to rSV40 vectors, rAd virus is generated in a helper cell line that provides the viral proteins in trans. The practical utility of adenoviral vectors in gene therapy is limited by the highly immunogenic nature of the viral proteins, and repeated administration of the vector often produces neutralizing antibodies in the host that can block gene transfer. Moreover, anti-Ad cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) attack virus-infected host cells causing a rapid loss of the transgene (55). Although vectors devoid of viral structural genes have been developed to prevent de novo expression of Ad genes, they exhibit prolonged transgene expression (56). Immunogenicity can be retained due of the presence of viral proteins that are produced in trans by the packaging cells during the generation of the rAd (57). Therefore, repeated gene transfer requires the generation of vectors with a different strain of adenovirus, which becomes impractical for the long-term.

To overcome this problem, alternative strategies have been explored, such as the expression of immunomodulatory genes to induce tolerance against adenoviral antigens in the host and abrogate the Ad-specific host immune response (58). This approach was successful in nullifying the humoral and cell-mediated immune response against adenoviral antigens in rodents in utero (59), newborn rats (60), and in adult rats (61, 62). By administering CTLA4-Ig and CD-40 antibodies, studies were conducted to inhibit co-stimulation between antigen presenting cells and CTLs in rodents but they only had limited success (63). In addition, recent attempts using hepatic delivery of Ad vectors for various disorders such as hyperbilirubinemia (64), estrogen-induced cholestasis (65), and autosomal dominant familial hypercholesterolemia (66) also met with relatively poor results. Although the administration of Ad vectors in experimental animals was proven to be effective, safety concerns remain because the wild type, adenoviruses are pathogenic in humans.

Oncolytic Adenovirus

Oncolytic adenoviruses have been modified in various ways to improve their specificity for cancer cells by combining tumor suppressor genes with oncolytic genes to induce cancer cell death. In one study, the α-fetoprotein (AFP) promoter has been used with the anti-tumor gene cytosine deaminase in oncolytic adenoviruses to enhance both the toxicity and the liver specificity of oncolytic adenoviral cancer therapy (67). In addition, it was recently shown that by overexpressing four copies of microRNA-199 cloned in the disrupted E1A gene of replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus, the virus could be used to treat liver cancer without causing significant hepatotoxicity (68).

Recombinant Baculovirus

The baculovirus expression system is commonly used to generate recombinant proteins in insect cells at high production levels. It has been shown that hepatocytes can be infected by baculoviral vectors derived from the recombinant baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis (AcNPV) (69). Recombinant baculoviruses can accommodate large segments of foreign DNA. These vectors consisting of baculoviral sequences and those of other viruses are being used to evaluate the extent of hepatic infection (70), and to study the cell death of HepG2 liver cancer cells in vitro (71). Even though they have been very useful in these studies, gene transfer efficiency and immunogenicity of recombinant baculoviruses in vivo requires additional characterization.

Table 2 summarizes the features of liver-directed viral gene therapy methods.

TABLE 2.

Features of Liver-Directed Viral Gene Therapy Methods

| Method | Integration and persistence | In vivo gene transfer efficiency to liver | Liver-specificity | Immunological* and other issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| RECOMBINANT VIRAL VECTORS: | ||||

| Murine leukemia-based retroviruses | Integration is required. | Requires mitosis. Low efficiency in quiescent cells types, e.g hepatocytes. | None | Non-immunogenic. Difficult to obtain very high titers. Envelope can be pseudotyped with other proteins to increase stability and broaden host range. |

| Lentivirus-based retroviruses | Integration is required. | Can infect non-dividing cells, but cell cycling may be needed. Low to intermediate efficiency for liver. |

None | Non-immunogenic. Difficult to obtain very high titers. Envelope can be pseudotyped with other proteins to increase stability and broaden host range. |

| Adeno-associated virus | Can exist in both episomal and integrated forms. | Can infect quiescent and dividing cells. Low to intermediate efficiency for liver. |

None | Causes humoral immune response. Can be grown at high titers. Site-specificity of integration of the wild type virus is lost in the absence of rep. Can undergo lytic cycle in the presence of helper proteins. Limited packaging space. |

| Adenovirus | Episomal. Can persist for several months in the absence of host immune response. |

Efficiently infects both dividing and non-dividing cells. Very high efficiency for liver. |

Liver targeted | Evokes both humoral and cell-mediated host immune response. Viral gene deletion reduces primary immunogenicity, but does not permit repeated injection. Host tolerization permits repeated gene transfer. |

| Hybrid viruses | Combines advantages of different viruses. | Efficiency of adenoviral vectors is combined with persistent nature of other viruses. | Liver targeted | Adenoviral proteins provided in trans may evoke immune response. Site-specific integration or episomal replication may be possible. |

| Simian virus 40 | Can exist in both episomal and integrated forms. | Infects both quiescent and dividing cells. High efficiency. |

None | No significant immune response. Can be grown at high titers. Limited packaging space. |

In all cases, an expressed transgene is potentially immunogenic in a mutant lacking the transgene product.

NON-VIRAL VECTORS

During the past decade, a number of novel methods have been developed to introduce foreign DNA into mammalian cells to correct genetic defects. While some of them have resulted in successful outcomes, others faced a number of challenges. These difficulties include insufficient gene delivery and inefficient targeting of the gene of interest. Recently developed genome engineering approaches appear to overcome many of these challenges. However, the successful transition from bench to bedside has been slow.

Sleeping Beauty Transposons

The expression of episomal DNA is inherently a transient, long-term expression that requires a mechanism that allows its integration into the host genome. Sleeping Beauty, a transposon system originally found as a mutated dormant form in salmonid fish (72) has been widely used to promote the integration of transgenes in mammalian cells at TA dinucleotide sites via a cut and paste mechanism (73). Recently, Sleeping Beauty has been successfully used in long-term amelioration of hemophilia B in UGT1A1-deficient Gunn rats (74). The system consists of plasmid(s) containing two transcription units, one expressing the enzyme Sleeping Beauty transposase, and the other expressing the transgene DNA in either cis or trans. The transcription unit expressing the transgene DNA is flanked by inverted/direct repeat sequences that are cleaved by the transposase, resulting in the insertion of the transgene into the host genome (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sleeping Beauty transposon (SB-Tn) is a synthetic “cut-and-paste” DNA transposase system for gene transfer that was resurrected from inactive transposon elements found in salmonid fish. The transposase can be delivered in either cis (as shown in the figure) or trans with the target gene. When translated, the transposase excises the target gene from the plasmid at flanking IR/DR elements and pastes the target gene and the flanking IR/DR elements into chromosomes at random TA sites.

The Sleeping Beauty system, using hydrodynamic infusion (75) to deliver naked plasmid vectors to the liver, has been used successfully for persistent expression of coagulation factor IX (74), factor VIII (76), AAT (77), β-glucuronidase or α-L-iduronidase (78), and fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah) (79). In all these cases, significant-to-complete correction of the disease phenotype was observed. However, immune consequences resulting in loss of phenotypic correction were observed with both factor VIII (76) and α-L-iduronidase (78), in part related to the non-specific delivery of the naked DNA by hydrodynamic push to hepatocytes, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) and Kupffer cells. By coupling the Sleeping Beauty transposon system with targeted cell-type specific delivery, long-term factor VIII expression and phenotypic correction of the bleeding diathesis were achieved (80). These studies coupled with the genomic Sleeping Beauty-mediated insertion profile, which although not entirely random for the TA dinucleotides, indicate that Sleeping Beauty preferentially inserts transgenes into nontranscribed and intronic regions of the genome (81, 82). Sleeping Beauty was found to successfully supplement cytoprotective heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in transgenic mice with sickle cell anemia (83). In this study, a single plasmid vector was engineered with an albumin promoter-driven Sleeping Beauty transposase, a wild-type rat Hmox-1 transposable element in cis containing an SV40 enhancer and a Friend’s Spleen Focus-Forming Virus LTR promoter to ensure constitutive expression of the transgene in the liver.

The Sleeping Beauty transposon system has been approved by the FDA for testing in humans (84). It has been tested to insert a gene encoding a chimeric antigen receptor specific for CD19 in primary T cells (85), and to treat patients with B-lymphoid malignancies with adaptive immunotherapy (86, 87). However, efficient and safe methods to deliver Sleeping Beauty transposons to the liver of larger animals must be developed before LDGT trials can be undertaken in humans.

PiggyBac Transposons

The piggyBac (PB) transposon system was originally derived from the cabbage looper moth Trichoplusia ni (88). It can efficiently transpose mammalian genomes (89, 90), including mouse and human embryonic stem cells (91, 92); and has the ability to integrate relatively large transgenes (up to 100-kb) with high efficiency. The mobile element of PB is 2,427 bp in length with specific 13 bp inverted terminal repeats, and a PB transposase of 594 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 68 kDa. PB transposase utilizes a cut-and-paste reaction to insert the transposable DNA element into TTAA target sequences that are duplicated upon insertion (93). The transposons can be also be excised from the genome without leaving a footprint. Recently, a hyperactive PB transposase (containing 7 mutations) was developed that is capable of attaining high level expression of transgenes in primary human cells ex vivo and mouse liver cells in vivo (94). The PB technology was used to correct the FIX deficiency in hemophiliac mice (95), in addition to AAT deficiency in human iPS cells using a combination of PB and a zinc finger nuclease (96). A codon-optimized hyperactive PB transposase was also used to express AAT at high levels in mouse livers (97). These exciting findings suggest that the PB transposon combined with a hyperactive transposase can be an efficient vector system for applications in the liver both in vitro and in vivo.

PhiC31 Integrase

PhiC31 integrase is a serine recombinase derived from Streptomyces phage ϕC31 of Streptomyces soil bacteria (98). This enzyme can catalyze the precise, unidirectional recombination of attB containing transgenes with pseudo attP sites found in the mammalian genome resulting in stable integration of the transgene. There are a limited number of genomic pseudo attP sites in these cells, thus limiting the number of integration sites and the chances of insertional mutagenesis. One advantage of this system is that it is not limited by vector size. It has been used recently to achieve sustained therapeutic expression of factor VIII and FIX by the liver and reduce the bleeding times in FVIII and FIX deficient mice (99, 100).

Both PhiC31 and Sleeping Beauty systems have been used to effectively integrate GFP into cultured rat multipotent adult progenitor cells (rMAPC). Southern blot analysis of G418-resistant rMAPC clones showed a 2-fold higher number of Sleeping Beauty-mediated insertions per clone compared to PhiC31. Sequence identification of chromosomal junction sites indicated a random profile for Sleeping Beauty-mediated integrants and a more restricted profile for PhiC31 integrants. Transgenic rMAPC generated with both systems maintained their ability to differentiate into liver and endothelium albeit with marked attenuation of GFP expression (101). Based on these results, the PhiC31 integrase holds great promise for both liver and stem cell directed gene therapies.

The features of liver-directed non-viral gene therapy methods are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Features of Liver-Directed Non-Viral Gene Therapy Methods

| Method | Integration and persistence | In vivo gene transfer efficiency to liver | Liver-specificity | Immunological*, integration site and transgene size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| NON-VIRAL VECTORS: | ||||

| Sleeping Beauty Transposons | Permanent | High efficiency | Liver targeted | Probably non-immunogenic; preferentially inserts transgenes into TA dinucleotide sites in nontranscribed and intronic regions; ~10kB - efficiency decreases with transgene size |

| PiggyBac Transposons | Permanent | High efficiency | Liver targeted | Probably non-immunogenic; ability to integrate relatively large transgenes (up to 100-kb); TTAA target sequences |

| PhiC31 Integrase | Permanent | High efficiency | Liver targeted | Probably non-immunogenic; unlimited transgene size; integrates in mammalian genome at pseudo attP sites |

Delivery of Non-viral Vectors

Over the years, a number of methods to deliver non-viral vectors to target organs have been developed, and reviewed recently in detail (102–104). For the delivery of these vectors to the liver, hydrodynamic injection is an effective method (105, 106). It involves rapid injection of a large volume of solution containing the vector into a blood vessel to enhance the permeability of the endothelium and the plasma membranes of parenchymal cells. This method was highly efficient for gene delivery and expression in rodents (107, 108) and in dogs (109). However, this method is less efficient in larger animals, such as pigs (110, 111), due to low level of mRNA translation of the injected DNA. On the other hand, naked plasmid DNA injected directly into the liver via an angio-catheter had better success in pigs, and expressed the green fluorescent protein encoded by the marker gfp gene on the plasmid (112).

For the delivery of transgenes, lipoplexes and polyplexes are widely used as non-viral gene delivery carriers (113). These are either lipid-nucleic acid or cation-nucleic acid complexes that are taken up into cells primarily by one of two basic mechanisms involving caveolae or clathrin-coated pits (114). Cations used in polyplex systems can be composed of polyehtylenimine (PEI), poly-L-lysine, polyglucosamines, lipopolyamines or cationic peptides (102–104). Both lipo- and lipoplexes have been used to deliver non-viral vectors to hepatocytes in the livers of rodents and nonhuman primates (115–117). Use of compounds targeting hepatocyte-specific receptors, such as the triantennary N-acetyl galactosamine that binds to the asialoglycoprotein receptor, and modified lipoplexes (118) enhance the delivery of transgenes to liver cells (119). The recent development of new methods and delivery vehicles, including a wide range of nanoparticles (120), underscores the fact that the liver-targeted gene delivery continues to develop. Most notably, the myriad of issues, such as poor transfection efficiency, insufficient retention of non-viral vehicles in the liver and undesirable side effects remain major challenges for LDGT (121).

TARGETED GENE EDITING

Various genetic disorders of the liver can be attributed to changes in a single gene. Because of this, the concept of treating such diseases at the genetic point of origin is very appealing. Such an approach involves correction of defective gene by homologous recombination without adding any extraneous DNA sequences that are potentially harmful. In the past few years, there has been a surge in LDGT studies using a number of very innovative methods that have led to some exciting results, suggesting that the effective gene therapy of acute liver disorders is within our reach.

Homologous Recombination

In an ideal scenario, the accurate means of repairing a mutated or damaged DNA occurs when a modified gene of interest is successfully transferred into cells and integrated into its homologous location at the target site in the genome. Genetic studies carried out in bacteriophage and yeast have led to strategies for gene targeting in higher organisms, although scarce and inconsistent biochemical and genetic data made in-depth identification of precise mechanisms challenging. In spite of an explosive increase in studies designed to characterize the various genomic DNA repair pathways in cultured cells from higher eukaryotes, successful targeted modification of genomic DNA by homologous recombination has been limited owing to a number of significant factors (122). First, the integration of exogenous DNA into the genome is extremely inefficient, and can occur in the absence of sequence homology between the introduced gene and genomic integration site (123). Second, as a defensive strategy, sequences in the chromatin are sequestered, thus promoting a low efficiency of pairing between the introduced DNA and its genomic target (124). However, targeted gene disruption to establish the functional activity of a particular gene in vitro has been quite successful.

Advances in our understanding of the regulation of homologous recombination in mammalian cells have opened the door for developing only the desired integration at the target site. Successful in vivo gene repair of β-glucuronidase (125) and Fah deficiency (126) has been achieved in the livers of transgenic mice by using rAAV vectors as a source of the single-stranded DNA. Nevertheless, it cannot be overlooked that in the in vivo setting, improving the frequency of targeted genes is especially challenging as it requires inactivation of other DNA repair proteins and/or pathways, which is difficult to achieve (122).

Single Nucleotide Modifications

Although exceptionally controversial because of irreproducibility, “chimeraplasty” was an approach to gene therapy that harnessed endogenous cell repair pathways as a means to specifically and permanently correct single base pair mutations. The technology was based on chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides that were specifically designed to correct point mutations in genomic DNA (127). The primary role of the RNA/DNA hybrid strand was to increase structural stability and enhance pairing with the target DNA. Chimeraplasty developed from data showing a significant increase in efficiency of pairing between an oligonucleotide ~ 50 bases long and a genomic DNA target, if RNA replaced DNA in a portion of the targeting oligonucleotide (128). In the original design, two single-stranded ends, comprised of unpaired nucleotide hairpin caps, flanked the double-stranded region of the chimeric molecule. The 5’ and 3’ ends are juxtaposed and sequestered; and together with 2’-O-methylated modification of the RNA residues contributed to enhanced nuclease resistance of the chimeraplast. The length of the oligonucleotide dictated the extent of homology between the chimeraplast and its genomic target; a 68-mer is designed to include a 25 bp region of homology containing a single mismatch with the gene sequence. This engineered mismatch was designed to initiate modification of the genomic target with the chimeraplast acting as a template for the alteration of the DNA sequence. The process appears to harness the efficient, endogenous DNA repair activity used to repair mutations caused by natural and artificial mutagens for the targeted modification of genes. The sequestered 5’ and 3’ ends minimized end-to-end ligation while the RNA segments, the region of homology and the “nick” are all essential for chimeraplast activity. The physical and enzymatic stability conferred by its secondary structure and the modified RNA helped to ensure the survival of the chimeraplast en route to and within the cell. While early results using chimeraplasty were very exciting (106a), it remains to be seen whether the technology will resurface as a viable approach to gene repair.

Single-Stranded Oligonucleotides (SSOs)

Interestingly, investigation of chimeraplast-directed targeted gene conversion demonstrated that SSOs could promote targeted single base exchange (129). The overall rate of targeted nucleotide replacement with these oligonucleotides was subsequently enhanced > 10-fold by transcriptional activation of the targeted loci (130). In hepatocytes, SSOs are either accumulated in lysosomes or follow a functional uptake pathway involving a novel clathrin- and caveolin-independent endocytic process to reach their target mRNA (131). SSO-mediated gene correction using polylysine-conjugates targeted to the hepatocyte ASGPR was successful in correcting the α-D-glucosidase gene (132), and in transgenic mice expressing the mutant murine transthyretin (TTR) gene. Targeted nucleotide replacement leading to gene repair was achieved in 9% of the adult mouse hepatocytes with phenotypic hepatic changes (133). In another study, 45-mer SSOs modified at their 3’ end with 3-phosphorotioate residues and phosphorylated at their 5’ end were delivered to transgenic spfash ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficient pups resulting in restoration of enzymatic activity to 15% of wild-type, reflected in the ~ 10 to 15% conversion of the targeted nucleotide from the mutant A to wild-type G (134). Despite these successful in vivo applications of SSOs, studies on LDGT with SSOs are still in their infancy.

Triplex DNA

Triplex DNA leverages the formation of a three-stranded or triple-helical nucleic acid structure to perform site-specific modification of genomic DNA (135). Essentially, the exogenous third strand of nucleic acid binds in the major grove of a homopurine region of the DNA, forming Hoogsteen or reverse Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds with the purine base (136). The triplex formation can occur at physiologic pH, but the polypurine regions must be guanine rich and 12 to 14 nucleotides in length for adequate triplex formation to occur. Additionally, monovalent cations such as Na+ and K+ inhibit triplex formation, rendering their formation under physiologic conditions difficult. Modified bases such as the thymidine purine analog 7-deaza-2’-deoxyxanthosine can counteract the inhibitory effect of monovalent cations on triplex formation, as well as maintaining an all purine backbone motif (137).

The initial approach to the triple-helix site-directed modification of DNA used cross-linking agents, such as psoralen or other mutagens covalently attached to the triplex forming oligonucleotide (135). This technique has been used to modify episomal DNA in mammalian cells in vitro (138), and to create targeted gene knockouts of the genomic hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase gene in cultured cells (139). Surprisingly, the majority of the knockouts resulted predominately from small deletions and some insertions, suggesting that the endogeneous mismatch repair pathway was not involved. Further investigation indicated that these triple-helix forming oligonucleotides could promote insertions and deletions at target sites in the absence of cross-linking agents, by inducing recombination via a nucleotide excision repair pathway (140). It is now well established that triplex DNA-mediated recombination is not affected in mismatch repair-deficient cells.

The problem of sequence constraint for triple-helix formation has been overcome, in part, by the use of novel approaches such as bifunctional oligonucleotides (141). These oligonucleotides contain regions that form triple-helical structures as well as conventional Watson and Crick base pairs. These modified oligonucleotides have been used successfully to promote site-specific nucleotide correction and gene targeting in both cell-free systems and cultured cells (142). These triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) can be used to modulate expression of genes involved in liver fibrosis by targeting them to hepatic stellate cells (143–145). Targeted inhibition of c-Met gene by TFOs in HepG2 cells was shown recently to induce cell death and regression of diethylnitrosamine-induced liver tumors in rats (146). Taken together, these findings suggested that this form of genomic modification might have therapeutic potential in treating certain liver disorders.

Zinc-finger Nucleases (ZFNs)

A relatively new approach to targeted gene replacement has been developed based on the use of ZFNs (147). ZFNs are artificial restriction enzymes generated by fusing a zinc finger DNA-binding domain to a DNA-cleavage domain (Figure 4). Zinc finger domains can be designed to target desired DNA sequences and this enables ZFNs to target unique sequences within complex genomes. By taking advantage of endogenous DNA repair machinery these reagents can be used to precisely alter the genomes of higher organisms. The approach produced improved efficiency of gene targeting by introducing DNA double-strand breaks in target genes that stimulated endogenous homologous recombination machinery (147, 148). This strategy can be designed to specifically target unique DNA sequences, allowing almost any region of the genome to be targeted. Gene replacements with engineered ZFNs as large as 7.7 kb have been efficiently introduced into the host genome of mammalian cells (149), and have been used successfully to selectively target and degrade mutated mitochondrial DNA in cultured cells (150).

Figure 4.

Zinc-finger nucleases are designed so that their zinc-finger domains will recognize specific sites near the mutation. The nuclease domains introduce a double-strand break into the DNA. A wild-type (non-mutated) sequence is introduced into the cells and used as the template for a cellular repair process, termed homologous recombination, in which the mutant sequence is corrected. (Reproduced from reference 204, with permission)

The significant enhancement in targeted gene replacement stimulated by ZFNs indicates its potential for use in quiescent cells such as hepatocytes. In fact, in vivo genome engineering was successfully used to correct the FIX deficiency and prolonged bleeding times in a mouse model of hemophilia B using ZFNs (151). rAAV vectors in combination with ZFNs was also recently used to correct the bleeding diathesis in adult hemophiliac mice (152). A combination of ZFNs with piggyBac vectors was recently shown to correct AAT deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells (96).

Transcription Activator-like Effector Nucleases (TALENs)

In the past few years, TALENS have rapidly developed into a promising technology for targeted genome editing in mammals and human induced pluripotent stem cells (153–155). TALENs are artificial nucleases capable of cleaving specific target DNA sequences in vivo (156) (Figure 5). TALENs utilize repeating units of transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) as a DNA recognition module and a FokI catalytic nuclease domain as the DNA cleavage module (157). TALEs are naturally occurring bacterial proteins used by plant pathogenic bacteria in the genus Xanthomonas to modulate gene transcription in host plants. TALEs consist of repeating domains of 33–35 amino acids. Each repeating unit is largely identical except for two amino acids at positions 12 and 13, referred to as the repeat variable di-residues (RVDs), which specifically recognize a single nucleotide. Thus the RVD region of each TALE module provides DNA recognition specificity. This simple di-amino acid/DNA recognition code and its modular nature make TALEs ideal for creating custom-designed targeted DNA nucleases.

Figure 5.

TALENs can be used to generate site-specific double strand breaks to facilitate genome editing through nonhomologous repair or homology directed repair. Two TALENs target a pair of binding sites flanking a 16-bp spacer. The left and right TALENs recognize the top and bottom strands of the target sites, respectively. Each TALEN DNA-binding domain is fused to the catalytic domain of FokI endonuclease; when FokI dimerizes, it cuts the DNA in the region between the left and right TALEN-binding sites. (Modified from reference 205)

The unique features of TALENs can be used to facilitate targeted gene editing. This involves homologous recombination (HR) of chromosomal DNA with the desired exogenous DNA and provides a precise method to edit mammalian genomes. The rates of recombination in mammalian cells typically fall in the range of 106–105 events per cell per generation, which is an inherent limitation of this technique. However, chromosomal double strand breaks such as those catalyzed by TALENs at a desired chromosomal locus can stimulate HR by > 1000 fold to facilitate targeted gene editing (137). Thus, TALENs represent a new and powerful gene editing approach to correct disease-causing genetic mutations. Using this technology, UGT1A1-deficient mouse liver cell lines were generated to study the CN1 disease (158); and complete silencing of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1 (DGAT1) was achieved to abrogate the entry of HCV in Huh-7.5 cells (159).

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 System

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is the most recent RNA-guided endonuclease technology for genome engineering in mammalian cells (Figure 6). CRISPR/Cas systems constitute a class of adaptive immune defense systems that protect bacteria and archaea from invading phages, viruses and plasmids via a RNA-guided DNA cleavage mechanism (160, 161). CRISPR loci consist of several noncontiguous highly conserved repeats that are separated by stretches of variable sequences termed as spacers. The sequences of spacers correspond to the viral and plasmid sequences that are captured during their recognition by bacteria and archaea. Quite often spacers are found adjacent to groups of highly conserved protein gene family called cas genes (160, 162). Recently CRISPR/Cas systems have been classified into three distinct types: type I, type II and type III (161, 163). While types I and III are found in both bacteria and archaea, type II is unique to bacteria.

Figure 6.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted genome editing. Initially, RNA-guided Cas9 generates a blunt-ended double-stranded break (DSB) 3 bp upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence. DSBs are then repaired either by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated disruption or by homology-directed repair (HDR)-mediated modification of the genome. gRNA: single stranded guide RNA.

The bacterial CRISPR/Cas system is the most studied and best characterized of the three types of which Cas9 protein is the critical component. In the bacterial type II system, CRISPR loci are transcribed as a precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) containing the full set of CRISPR repeats and embedded invader-derived sequences (164). A trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) binds to the repeat sequences of the pre-crRNA to form a duplex RNA, which is then cleaved by a double-stranded RNA-specific ribonuclease RNase III, the Cas9 protein (161, 163–167). Thus, the CRISPR/Cas9 typically contains a minimal set of two components: a single-stranded guide RNA (gRNA) and an endonuclease. RNA-guided Cas9 activity creates site-specific double-stranded breaks in the target genome that are repaired by either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) (168, 169). In recent years, type II bacterial CRISPR/Cas9 system has been successfully applied to various mammalian cell types, including in mouse, rat, and human cells, using an engineered guide RNA and Cas9 endonuclease (166, 168, 169).

The CRISP/Cas9 is a versatile, high efficiency technology that is easy to use and capable of modifying any gene of interest (166). Moreover, the functionality of CRISPR/Cas9 system allows for targeting of multiple genes simultaneously by using multiple gRNAs (169, 170). CRISPR/Cas9 system was successfully used to correct Fah mutation I the mouse model of hereditary tyrosinemia (171), and to mutate cancer genes in the mouse liver by targeting p53 and PTEN genes (172). These studies demonstrate the potential of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing for the correction of human genetic diseases.

Despite these promising advances, this method of gene modifications suffers from a number of limitations. These include a high frequency of off-target effects, as shown recently with human cells (173, 174), imperfect Cas9 specificity, and sequence requirements within the CRISPR motifs termed as protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences that may restrain some applications (175). It was reported that HDR can be facilitated with greater target specificity by using a Cas9 mutant Cas9n that can cleave only a single DNA strand (168). When combined with paired gRNAs, Cas9n was shown to cleave double-stranded DNA with high efficiency and low off-target effects (176), and off-target Cas9 activity can also be drastically reduced by selecting gRNAs with few off-target sites of near complementarity (177). Another area of concern is the possible induction of immune responses in host cells in response to the bacterial enzyme Cas9, if it is recognized as ‘foreign’. This could potentially limit the efficacy of the CRISPR/Cas9 approach in humans.

The Precise Integration into Target Chromosome (PITCh) System

The PITCh system is the latest addition to the genome engineering technology. Using a novel microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) approach, successful knock-ins were recently achieved both in human cell lines and in animals, including silk worms and frogs, with the PITCh approach (178). Interestingly, endonucleases from either the TALEN or CRISPR system can be used with this method to generate genome cleavage in the target cell. Unlike the homologous recombination-mediated repair mechanism of TALENs and CRISPRs that is active during late S/G2 phases of the cell cycle, the MMEJ repair mechanism is active during the G1/early S phase. This difference enables it to create an efficient, targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in various cell lines and organisms, even in those that have low level activities of homologous recombination (178). Because of the ease with which the vector constructs can be generated, the PITCh system is a simpler and alternative strategy for genome targeting, with potential applications in the liver.

OTHER APPROACHES

LDGT approaches in the recent past also involved RNA interference (RNAi), ribozymes, and antisense oligonucleotides (siRNAs). These methods use small oligos to regulate the gene expression in target cells following their delivery, as shown recently with the modulation of hepatic gene expression in vivo by oligos delivered via the hydrodynamic injection (179–181). However, hydrodynamic delivery of naked siRNAs results in immune activation and may cause damage to the target organ (182). Potential gene therapy applications and pitfalls of each of these approaches have been discussed recently in excellent reviews (183–186). Although the outcomes from studies using these methods are encouraging, they have not yet reached a stage to markedly influence our clinical future.

PERSPECTIVES

The potential of exciting new gene therapy technologies, most notably genome modifications using ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPRs is evident from the surge in the research activity during the past few years. Each of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages (Table 4). However, intense efforts are being made to overcome their weaknesses so that they can be applied for LDGT in humans. In fact, a number of gene therapy trials using viral and non-viral vectors targeting the liver are currently underway (42). Up-to-date information on these trials is available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ and http://www.abedia.com/wiley. Data from animal models suggest that several different gene replacement strategies may eventually yield long-term expression of transgenes at therapeutic levels, and that in situ correction of gene defects in hepatocytes may eventually be a therapeutic option (26). Recently developed Cas9 transgenic mice (187) will greatly facilitate the studies on genome engineering for disease modeling of human liver disorders, and AAV vectors will allow robust and specific delivery of gRNAs and Cas9 protein to cells that are difficult to transfect (188). There has been some success with various gene therapy approaches, mostly employing AAV, targeting liver diseases and disorders such as hemophilia (26, 38, 189–192), AAT deficiency (193–195), lysosomal storage disease (196, 197), acute intermittent porphyria (198), lipoprotein metabolism (199), familial hypercholesterolemia (200), inherited hyperbilirubinemia (201), and citrullinemia type 1 (202). In addition, novel AAV vectors generated using adenoviruses characterized from porcine tissues (203) will allow us to refine the gene therapy techniques for use in large animal models, and for the development of therapies for human diseases. The promises made more than 20 years ago are now becoming a reality, based in large part on significant technical advances and lessons learned, both good and bad.

TABLE 4.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Gene Editing Methods

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ZFNs | Short time-course (~ 6 months) High frequency of targeted gene disruption |

Screening and assembly is technically challenging Requires extensive screening to detect target events High level of off-target effects Commercially available modules are expensive Difficult to perform large fragment (> 1 kb) replacement |

| TALENs | Unconstrained target site requirements High degree of specificity Low off-target effects Little evidence of mismatch tolerance |

Sensitive to cytosine methylation, especially at CpG dinucleotides |

| CRISPRs | High target site specificity High frequency of gene targeting Ease of design and construction |

gRNAs can tolerate up to five mismatches with unwanted target sites High level of indel formation at unintended sites High level of off-target effects |

REFERENCES

- 1.Ozaki I, Zern MA, Liu S, Wei DL, Pomerantz RJ, Duan L. Ribozyme-mediated specific gene replacement of the alpha1-antitrypsin gene in human hepatoma cells. J Hepatol. 1999;31(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaglioni P, Malegari M, Takahashi M, Chowdhury JR, Wands J. Use of dominant negative mutants of the hepadnaviral core protein as antiviral agents. Hepatology. 1996;24(5):1010–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokoris MS, Sabo P, Adman ET, Black ME. Enhancement of tumor ablation by a selected HSV-1 thymidine kinase mutant Gene Ther. 1999;6(8):1415–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullen CA, Coale MM, Lowe R, Blaese RM. Tumors expressing the cytosine deaminase suicide gene can be eliminated in vivo with 5-fluorocytosine and induce protective immunity to wild type tumor. Cancer Res. 1994;54(6):1503–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohr L, Shankara S, Yoon SK, Krohne TU, Geissler M, Roberts B, Blum HE, Wands JR. Gene therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo in nude mice by adenoviral transfer of the Escherichia coli purine nucleoside phosphorylase gene. Hepatology. 2000;31(3):606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth JA, Nguyen D, Lawrence DD, Kemp BL, Carrasco CH, Ferson DZ, Hong WK, Komaki R, Lee JJ, Nesbitt JC, Pisters KM, Putnam JB, Schea R, Shin DM, Walsh GL, Dolormente MM, Han CI, Martin FD, Yen N, Xu K, Stephens LC, McDonnell TJ, Mukhopadhyay T, Cai D. Retrovirus-mediated wild-type p53 gene transfer to tumors of patients with lung cancer. Nat Med. 1996;2(9):985–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank DK, Frederick MJ, Liu TJ, Clayman GL. Bystander effect in the adenovirus-mediated wild-type p53 gene therapy model of human squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(10):2521–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paillard F Immunosuppression mediated by tumor cells: a challenge for immunotherapeutic approaches. Human Gene Ther. 2000;11(5):657–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blezinger P, Wang J, Gondo M, Quezada A, Mehrens D, French M, Singhal A, Sullivan S, Rolland A, Ralston R, Min W. Systemic inhibition of tumor growth and tumor metastases by intramuscular administration of the endostatin gene. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(4):343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Cao Y, Folkman J, Fine HA. Viral vector-targeted anti-angiogenic gene therapy utilizing an angiostatin complementary DNA. Cancer Res. 1998;58(15):3362–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs F, Gordts SC, Muthuramu I, De Geest B. The liver as a target organ for gene therapy: state of the art, challenges, and future perspectives. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012;5(12):1372–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu SM, Hochedlinger K. Harnessing the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(5):497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YF, Tseng CY, Wang HW, Kuo HC, Yang VW, Lee OK. Rapid generation of mature hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells by an efficient three-step protocol. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, North PE, Dalton S, Duncan SA. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller AD. Development of applications of retroviral vectors. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Vermus HE, eds Retroviruses Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press. 1997:437–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma IM, Somia N. Gene therapy – promises, problems and prospects. Nature. 1997;389(6648):239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fassati A, Goff SP. Characterization of intracellular reverse transcription complexes of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1999;73(11):8919–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elis E, Ehrlich M, Prizan-Ravid A, Laham-Karam N, Bacharach E. p12 tethers the murine leukemia virus pre-integration complex to mitotic chromosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(12):e1003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L, Mei M, Ma X, Ponder KP. High expression reduces an antibody response after neonatal gene therapy with B domain-deleted human factor VIII in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(9):1805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay MA. State-of-the-art gene-based therapies: the road ahead. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(5):316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferry N, Pichard V, Sébastien Bony DA, Nguyen TH. Retroviral vector-mediated gene therapy for metabolic diseases: an update. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(24):2516–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young GR, Stoye JP, Kassiotis G. Are human endogenous retroviruses pathogenic? An approach to testing the hypothesis. Bioessays. 2013;35(9):794–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mátrai J, Cantore A, Bartholomae CC, Annoni A, Wang W, Acosta-Sanchez A, Samara-Kuko E, De Waele L, Ma L, Genovese P, Damo M, Arens A, Goudy K, Nichols TC, von Kalle C, L Chuah MK, Roncarolo MG, Schmidt M, Vandendriessche T, Naldini L. Hepatocyte-targeted expression by integrase-defective lentiviral vectors induces antigen-specific tolerance in mice with low genotoxic risk. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1696–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annoni A, Brown BD, Cantore A, Sergi LS, Naldini L, Roncarolo MG. In vivo delivery of a microRNA-regulated transgene induces antigen-specific regulatory T cells and promotes immunologic tolerance. Blood. 2009;114(25):5152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown BD, Cantore A, Annoni A, Sergi LS, Lombardo A, Della Valle P, D’Angelo A, Naldini L. A microRNA-regulated lentiviral vector mediates stable correction of hemophilia B mice. Blood. 2007;110(13):4144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.High KH, Nathwani A, Spencer T, Lillicrap D. Current status of haemophilia gene therapy. Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 4):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martino AT, Suzuki M, Markusic DM, Zolotukhin I, Ryals RC, Moghimi B, Ertl HC, Muruve DA, Lee B, Herzog RW. The genome of self-complementary adeno-associated viral vectors increases Toll-like receptor 9-dependent innate immune responses in the liver. Blood. 2011;117(24):6459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotterman MA, Schaffer DV. Engineering adeno-associated viruses for clinical gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(7):445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montenegro-Miranda PS, Pañeda A, ten Bloemendaal L, Duijst S, de Waart DR, Aseguinolaza GG, Bosma PJ. Adeno-associated viral vector serotype 5 poorly transduces liver in rat models. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e82597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montenegro-Miranda PS, Pichard V, Aubert D, Ten Bloemendaal L, Duijst S, de Waart DR, Ferry N, Bosma PJ. In the rat liver, adenoviral gene transfer efficiency is comparable to AAV. Gene Ther. 2014;21(2):168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samulski RJ, Zhu X, Xiao X, Brook JD, Housman DE, Epstein N, Hunter LA. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J. 1999;10(12):3941–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buller RM, Janik JE, Sebring ED, Rose JA. Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 completely help adenovirus-associated virus replication. J Virol. 1981;40(1):241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yakinoglu AO, Heilbronn R, Burkle A, Schlehofer JR, zur Hausen H. DNA amplification of adeno-associated virus as a response to cellular genotoxic stress. J Virol. 1988;48(11):3123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walz C, Schlehofer JR, Flentje M, Rudat V, zur Hausen H. Adeno-associated virus sensitizes HeLa cell tumors to gamma rays. J Virol. 1992;66(9):5651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yakobson B, Hrynko TA, Peak MJ, Winocour E. Replication of adeno-associated virus in cells irradiated with UV light at 254 nm. J Virol. 1989;63(3):1023–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakai H, Yant SR, Storm TA, Fuess S, Meuse L, Kay MA. Extrachromosomal recombinant adeno-associated virus vector genomes are primarily responsible for stable liver transduction in vivo. J Virol. 2001;75(15):6969–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathwani A, Tuddenham EG, Rangarajan S, Rosales C, McIntosh J, Linch DC, Chowdary P, Riddell A, Pie AJ, Harrington C, O’Beirne J, Smith K, Pasi J, Glader B, Rustagi P, Ng CY, Kay MA, Zhou J, Spence Y, Morton CL, Allay J, Coleman J, Sleep S, Cunningham JM, Srivastava D, Basner-Tschakarjan E, Mingozzi F, High KA, Gray JT, Reiss UM, Nienhuis AW, Davidoff AM. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(25):2357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z, Ye J, Zhang A, Xie L, Shen Q, Xue J, Chen J. Gene therapy for hemophilia B with liver-specific element mediated by Rep-RBE site-specific integration system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;65(2):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greig JA, Peng H, Ohlstein J, Medina-Jaszek CA, Ahonkhai O, Mentzinger A, Grant RL, Roy S, Chen SJ, Bell P, Tretiakova AP, Wilson JM. Intramuscular Injection of AAV8 in mice and macaques is associated with substantial hepatic targeting and transgene expression. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling C, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Ejjigani A, Yin Z, Lu Y, Wang L, Wang M, Li J, Hu Z, Aslanidi GV, Zhong L, Gao G, Srivastava A, Ling C. Selective in vivo targeting of human liver tumors by optimized AAV3 vectors in a murine xenograft model. Human Gene Ther. 2014;25(12):1023–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaudet D, Méthot J, Déry S, Brisson D, Essiembre C, Tremblay G, Tremblay K, de Wal J, Twisk J, van den Bulk N, Sier-Ferreira V, van Deventer S. Efficacy and long-term safety of alipogene tiparvovec (AAV1-LPLS447X) gene therapy for lipoprotein lipase deficiency: an open-label trial. Gene Ther. 2013;20(4):361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dijk R, Beuers U, Bosma PJ. Gene replacement therapy for genetic hepatocellular jaundice. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2014. Oct 16. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nietupski JB, Hurlbut GD, Ziegler RJ, Chu Q, Hodges BL, Ashe KM, Bree M, Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Scheule RK. Systemic administration of AAV8-α-galactosidase A induces humoral tolerance in nonhuman primates despite low hepatic expression. Mol Ther. 2011;19(11):1999–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, Ozelo MC, Hoots K, Blatt P, Konkle B, Dake M, Kaye R, Razavi M, Zajko A, Zehnder J, Rustagi PK, Nakai H, Chew A, Leonard D, Wright JF, Lessard RR, Sommer JM, Tigges M, Sabatino D, Luk A, Jiang H, Mingozzi F, Couto L, Ertl HC, High KA, Kay MA. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12(3):342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurlbut GD, Ziegler RJ, Nietupski JB, Foley JW, Woodworth LA, Meyers E, Bercury SD, Pande NN, Souza DW, Bree MP, Lukason MJ, Marshall J, Cheng SH, Scheule RK. Preexisting immunity and low expression in primates highlight translational challenges for liver-directed AAV8-mediated gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2010;18(11):1983–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lisowski L, Dane AP, Chu K, Zhang Y, Cunningham SC, Wilson EM, Nygaard S, Grompe M, Alexander IE, Kay MA. Selection and evaluation of clinically relevant AAV variants in a xenograft liver model. Nature. 2014;506(7488):382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie J, Ameres SL, Friedline R, Hung JH, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Zhong L, Su Q, He R, Li M, Li H, Mu X, Zhang H, Broderick JA, Kim JK, Weng Z, Flotte TR, Zamore PD, Gao G. Long-term, efficient inhibition of microRNA function in mice using rAAV vectors. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):403–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mueller C, Tang Q, Gruntman A, Blomenkamp K, Teckman J, Song L, Zamore PD, Flotte TR. Sustained miRNA-mediated knockdown of mutant AAT with simultaneous augmentation of wild-type AAT has minimal effect on global liver miRNA profiles. Mol Ther. 2012;20(3):590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sowd GA, Fanning E. A wolf in sheep’s clothing: SV40 co-opts host genome maintenance proteins to replicate viral DNA. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1002994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strayer DS. SV40-based gene therapy vectors: turning an adversary into a friend. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2000;2(5):570–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strayer D, Branco F, Zern MA, Yam P, Calarota SA, Nichols CN, Zaia JA, Rossi J, Li H, Parashar B, Ghosh S, Chowdhury JR. Durability of transgene expression and vector integration: recombinant SV40-derived gene therapy vectors. Mol Ther. 2002;6(2):227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arad U, Zeira E, El-Latif MA, Mukherjee S, Mitchell L, Pappo O, Galun E, Oppenheim A. Liver-targeted gene therapy by SV40-based vectors using the hydrodynamic injection method. Human Gene Ther. 2005;16(3):361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prevec L, Schneider M, Rosenthal KL, Belbeck LW, Derbyshire JB, Graham FL. Use of human adenovirus-based vectors for antigen expression in animals. J Gen Virol. 1989;70(Pt 2):429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jaffe HA, Danel C, Longenecker G, Metzger M, Setoguchi Y, Rosenfeld MA, Gant TW, Thorgeirsson SS, Stratford-Perricaudet LD, Perricaudet M, Pavirani A, Lecocq J-P, Crystal RG. Adenovirus-mediated in vivo gene transfer and expression in normal rat liver. Nat Genet. 1992;1(5):372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Y, Li Q, Ertl HCJ, Wilson JM. Cellular and humoral immune responses to viral antigen create barriers to lung-directed gene therapy with recombinant adenoviruses. J Virol. 1995;69(4):2004–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morral N, O’Neal W, Rice K, Leland M, Kaplan J, Piedra PA, Zhou H, Parks RJ, Velji R, Aguilar-Córdova E, Wadsworth S, Graham FL, Kochanek S, Carey KD, Beaudet AL. Administration of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors and sequential delivery of different vector serotype for long-term liver-directed gene transfer in baboons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(22):12816–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh SS, Takahaski M, Thummala NR, Parashar B, Chowdhury NR, Chowdhury JR. Liver-directed gene therapy: Promises, problems and prospects at the turn of the century. J Hepatol. 2000;32(1 Suppl):238–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ilan Y, Droguett G, Chowdhury NR, Li Y, Sengupta K, Thummala NR, Davidson A, Chowdhury JR, Horwitz MS. Insertion of the adenoviral E3 region into a recombinant viral vector prevents antiviral humoral and cellular immune responses and permits long-term gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(6):2587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lipshutz GS, Sarkar R, Flebbe-Rehwaldt L, Kazazian H, Gaensler KM. Short-term correction of factor VIII deficiency in a murine model of hemophilia A after delivery of adenovirus murine factor VIII in utero. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(23):13324–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi M, Ilan Y, Chowdhury NR, Guida J, Horwitz M, Chowdhury JR. Long term correction of bilirubin-UDP-glucuronosyltransferase deficiency in Gunn rats by administration of a recombinant adenovirus during the neonatal period. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(43):26536–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ilan Y, Attavar P, Takahashi M, Davidson A, Horwitz MS, Guida J, Chowdhury NR, Chowdhury JR. Induction of central tolerance by intrathymic inoculation of adenoviral antigens into the host thymus permits long-term gene therapy in Gunn rats. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(11):2640–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ilan Y, Prakash R, Davidson A, Jona, Droguett G, Horwitz MS, Chowdhury NR, Chowdhury JR. Oral tolerization to adenoviral antigens permits long-term gene expression using recombinant adenoviral vectors. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(5):1098–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kay MA, Meuse L, Gown AM, Linsley P, Hollenbaugh D, Aruffo A, Ochs HD, Wilson CB. Transient immunomodulation with anti-CD40 ligand antibody and CTLA4Ig enhances persistence and secondary adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(9):4686–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmitt F, Pastore N, Abarrategui-Pontes C, Flageul M, Myara A, Laplanche S, Labrune P, Podevin G, Nguyen TH, Brunetti-Pierri N. Correction of hyperbilirubinemia in Gunn rats by surgical delivery of low doses of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. Human Gene Ther Meth. 2014;25(3):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marrone J, Lehmann GL, Soria LR, Pellegrino JM, Molinas S, Marinelli RA. Adenoviral transfer of human aquaporin-1 gene to rat liver improves bile flow in estrogen-induced cholestasis. Gene Ther. 2014;21(12):1058–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oka K, Mullins CE, Kushwaha RS, Leen AM, Chan L. Gene therapy for rhesus monkeys heterozygous for LDL receptor deficiency by balloon catheter hepatic delivery of helper-dependent adenoviral vector. Gene Ther. 2014;22(1):87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu HN, Huang WD, Cai Y, Ding M, Gu JF, Wei N, Sun LY, Cao X, Li HG, Zhang KJ, Liu XR, Liu XY. HCCS1-armed, quadruple-regulated oncolytic adenovirus specific for liver cancer as a cancer targeting gene-viro-therapy strategy. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]