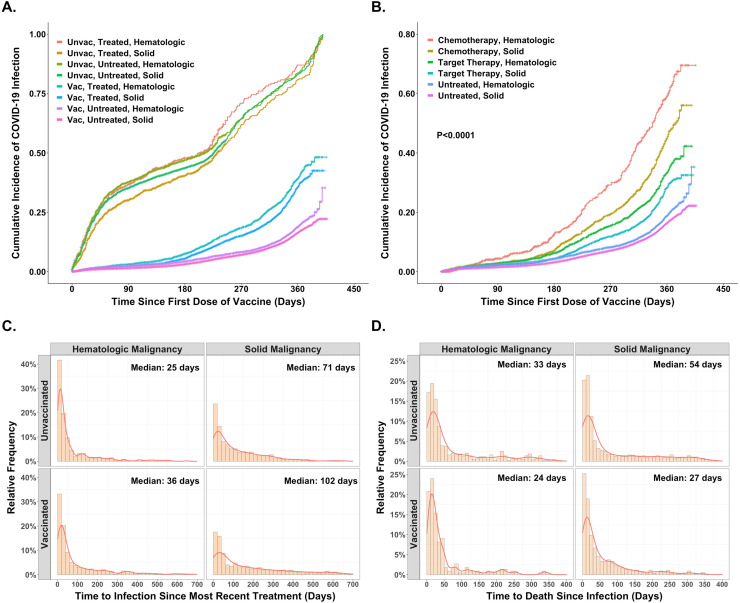

Fig. 5.

A and B compares the (cumulative) probability of infection in those who did or did not receive chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy for their cancer during the period of observation. Fig. 5A looks at the impact of vaccination status on the probability of infection presented according to a diagnosis of either a hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor. Fig. 5B compares the results in those treated with either chemotherapy or targeted therapies to those not treated according to their diagnosis of either a hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor. In both figures the order of the legend tracks with the curves from top to bottom. A total of 157,072 Veterans with a diagnosis of cancer were evaluated, with 19,307 having received one of the 82 therapies identified in Supplementary Table 1. Figs. 5C and D present distribution plots looking at the occurrence of infection or death following infection. The data are shown for those who had not been vaccinated separately from those who were vaccinated and presented separately for those with a diagnosis of either a hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor. The X-axis is time after the receipt of therapy and the Y-axis the percent of all those treated in whom infection or death was recorded in successive 20-day time intervals–each bar comprises 20 days. Fig. 5C shows the fraction of infections occurring closer in time to and more likely impacted by treatment was higher in the unvaccinated and those with hematologic malignancies. Fig. 5D peaks of death 4 weeks following infection consistent with most deaths more likely caused by the infection than as a result of the underlying disease.