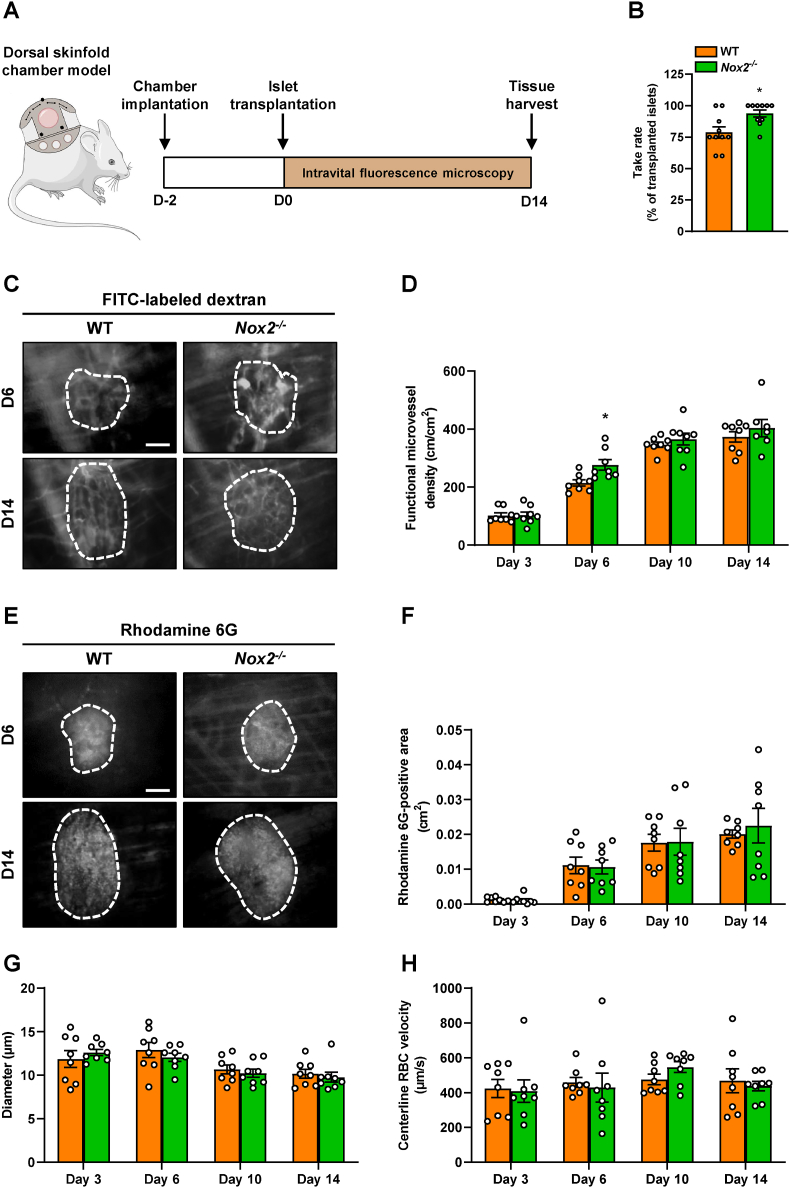

Fig. 4.

Loss of NOX2 accelerates revascularization of transplanted islets. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental setting. Dorsal skinfold chambers were implanted on day −2 followed by transplantation of WT and Nox2−/− islets on day 0. Intravital fluorescence microscopy was performed on days 3, 6, 10 and 14 after islet transplantation. On day 14, the tissue was harvested for immunohistochemical stainings. (B) Take rate of WT and Nox2−/− islets (% of transplanted islets) on day 14 after islet transplantation onto the exposed striated muscle tissue (n = 10 each). Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. WT. (C) Representative intravital fluorescent microscopic images of transplanted WT and Nox2−/− islets within the dorsal skinfold chamber on day 14. The plasma marker FITC-labeled dextran 150,000 was used for the visualization of blood-perfused microvessels. The border of the grafts is marked by white broken lines. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis of the functional microvessel density (cm/cm2) of WT and Nox2−/− islets (n = 8 each). Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. WT. (E) Representative intravital fluorescent microscopic images of transplanted WT and Nox2−/− islets within the dorsal skinfold chamber on day 14. Rhodamine 6G was used to visualize endocrine tissue perfusion (bright signals). The border of the grafts is marked by broken lines. Scale bar: 50 μm. (F–H) Quantitative analysis of the rhodamine 6G-positive area (cm2) (F), the microvessel diameters (μm) (G) and the microvessel centerline RBC velocities (μm/s) (H) within transplanted WT and Nox2−/− islets (n = 8 each). Mean ± SEM.