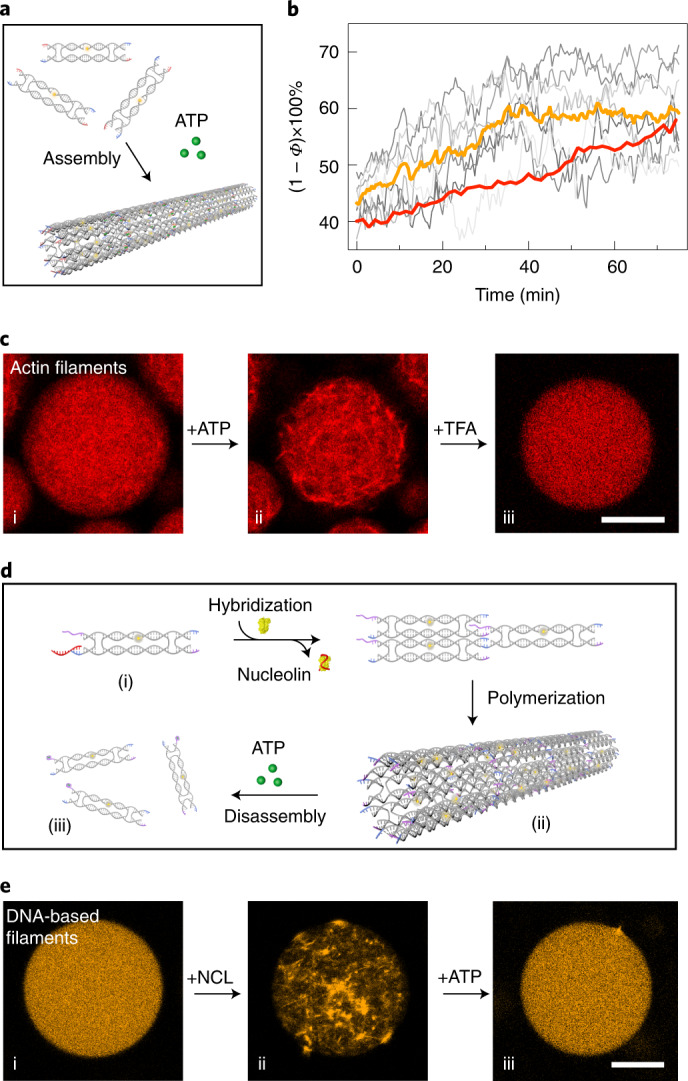

Fig. 3. Comparison between DNA-based and actin filaments in cell-sized confinement.

a, Schematic of polymerization of the DNA tiles containing split ATP aptamers upon addition of ATP. b, Normalized porosity ((1 − Φ) × 100%, corresponding to the degree of polymerization) in seven individual droplets (grey) and average polymerization for the DNA-based filaments (orange) and the actin filaments (red) over time during the polymerization processes. The degree of polymerization for the DNA-based filaments inside the droplets increases over time, until it reaches a dynamic steady state after 40 min. Actin filaments are polymerized at a comparable rate, reaching a similar degree of polymerization. c, Confocal microscopy images of droplets containing rhodamine-labelled actin filaments (λex = 561 nm) (i) directly after encapsulation, (ii) 30 min after addition of ATP and (iii) after subsequent addition of TFA. The actin filaments are assembled on adding ATP and are disassembled after adding TFA. d, Schematic of the dual-responsive DNA tile containing an NCL-specific aptamer to trigger assembly and an ATP-specific aptamer to trigger disassembly of the filaments. e, Confocal microscopy images of droplets containing dual-stimuli-responsive Cy3-labelled filaments (λex = 561 nm) (i) without NCL or ATP, (ii) after the addition of NCL and (iii) after the subsequent addition of ATP. The DNA-based filaments are assembled following the addition of NCL and subsequently disassembled after the addition of ATP. Scale bars, 20 μm.