Abstract

Background

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is the most common congenital endocrine disease with reported high prevalence of associated congenital anomalies which are also present in case of congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) infection.

Subjects and Methods

We present two cases of newborns cCMV infection with CH. In the first case thyroid agenesis was diagnosed and cCMV infection was also confirmed for the hypotonia persistence after L-thyroxine treatment. In the second case thyroid dyshormonogenesis was diagnosed with maternal CMV serological conversion in the first trimester of gestation and confirmed post-neonatal infection. Incidence of CH has increased in the Italian region of Piedmont in the years 2014-2019 up to 1:1090 with higher incidence of cCMV infection in the babies with diagnosis of CH (12/1000 vs. 5-7/1000 in the newborns without CH). To our knowledge, no data on the association of cCMV infection with a CH condition have been reported in the literature to date.

Conclusions

The described cases could be useful to alert caregivers in case of maternal seroconversion to avoid maternal and foetal hypothyroidism. On the other hand, when the clinical condition of newborns with CH diagnosis do not improve after l-thyroxine treatment, it might be important to consider cCMV infection.

Keywords: Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection, Congenital hypothyroidism, association, neonatal

Introduction

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH), the thyroid hormone deficiency since birth, is the most common congenital endocrine disease, which can lead to severe delay in neuropsychomotor development and growth failure if not treated promptly (1). The incidence of CH has classically been indicated as 1:3000-4000 births but in the last decades the incidence of this condition has grown progressively and the main reasons for this increase are related to the cut-off reduction of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) detection on Dry Blood Spot (DBS) in the neonatal screening strategy and to a higher rate of CH development risk factors. The factors that influence mostly the incidence of CH include current changes in the ethnicity of the population, the increase of preterm births, the iodine deficiency in the diet, the presence of syndromes associated with CH or genetic alterations in genes responsible for thyroid ontogenesis or function (2-3).

Thyroid dysgenesis, which includes total agenesis, ectopic (single or double foci) and hemiagenesis or hypoplasia, is responsible for 50-60 % of cases of CH. Thyroid dyshormonogenesis was classically reported in 15-25% of cases, but in recent years its incidence has increased to 40-50% (1-3).

Since the late 1980s, a high prevalence of congenital anomalies associated with CH has been reported, mainly cardiac defects, cleft palate and/or cleft lip, abnormalities of the urogenital, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal system, as well as chromosomal abnormalities (4-6).

On the other hand congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) infection, which occurs in 5-7 per 1000 live births, is associated with important permanent sequelae, such as sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), cognitive impairment, retinitis and cerebral palsy. Such sequelae occurr in 40-60% of symptomatic infants and 10-15% of asymptomatic newborns (7-9). The severity of the clinical condition is related to the pregnancy trimester of the maternal seroconversion or reinfection; the earlier the CMV infection, the greater the degree of severity of the clinical condition. The diagnosis in newborns is performed by detecting viral load in saliva or urine samples with real-time PCR (7-9).

To our knowledge, no data are currently present in literature on the association or causal role of cCMV infection in primary CH. We present a series of two cases of preterm newborns affected by cCMV infection and CH detection at neonatal screening.

Case presentation 1

A preterm female newborn (Gestational Age 34w+3), born by spontaneous delivery after preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM) was admitted at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) of our Department for severe Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) and general hypotonia. Family history was negative for remarkable information and pregnancy history reported only an assessment of abdominal circumference >95˚ percentile and polyhydramnios at the 33rd week of gestational age.

At the first clinical examination the newborn presented poor clinical conditions, with generalized diffused oedema and evident respiratory distress, which required ventilatory support first with invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and subsequently with high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC).

Renal function was initially compromised with high creatinine levels (0.78 mg/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (2.8 mg/dL), for which albumin and hydrations boluses were performed, with slow improvement of clinical oedema. Renal ultrasound showed mildly enlarged kidneys and thin renal cortex, without a clear interpretation of renal dysplasia.

Cardiac ultrasound showed patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) which was not resolved by medical treatment with ibuprofen, thus the surgical treatment was needed. In the postoperative period, the newborn experienced hypertension responsive to nifedipine 1 mg/day and progressive improvement of cardiac and renal functions (creatinine level 0.44 mg/dL), but persistence of hypotonia and RDS.

Meantime, the Neonatal Screening Center reported a high level of TSH (>1000 mcUI/L on DBS) confirmed at the biochemical investigations that revealed a very high serum level of TSH (744 mU/L), with low concentrations of free T4 (fT4) and free T3 (fT3) [1 pg/ml and 0.5 pg/mL respectively].

Thyroid ultrasound did not show the presence of any thyroid tissue. Clinical, biochemical and imaging investigations confirmed the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism due to thyroid agenesis.

Treatment with oral liquid levothyroxine was initiated at dose of 10.1 mcg/kg/day, with a rapid improvement in the respiratory condition and hypotonia, the withdrawal of oxygen supplementation and the start of autonomous feeding.

Subsequent biochemical investigations indicated regular improvement in thyroid hormones metabolism until the normalisation of fT4 and fT3 levels (19.7 pg/mL and 3.2 pg/mL, respectively) and the lowering of serum TSH levels (16.6 mUI/L), which normalized (1.31 mUI/L) 2 weeks after the treatment start, when she was 5 weeks-old.

Considering the prematurity of the baby, the associated RDS and generalized hypotonia and the persisting nutrition difficulties, a cerebral ultrasound was performed which revealed bilateral diffuse periventricular hyperechogenic areas and signs of vasculitis in the thalamic blood vessels (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cerebral ultrasound showing bilateral diffuse periventricular hyperechogenic areas and signs of vasculitis in the thalamic blood vessels.

As hypotonia persisted, metabolic screening was performed, including urinary organic acids, multiplex spot lysosomal activity, Very Long Chain Fatty Acids (VLCFA), as well as rapid karyotype analysis, DNA methylation test to exclude Prader-Willi syndrome and CGH arrays, all resulted normal.

A cCMV infection was therefore suspected and confirmed by the identification of CMV with high viral load (> 6.000.000 DNA copies/ml) in the urine sample and in plasma analysis, confirmed also on Guthrie card. Treatment with ganciclovir at dose of 6 mg/kg in one hour every 12 h/day for 6 weeks was then started, followed by oral valganciclovir at 16 mg/kg every 12 h/day for 6 months.

The audiometric assessment with auditory brainstem response (ABR) did not show pathological patterns associated to CMV infection. Liver enzyme profile was normal during the entire follow-up period.

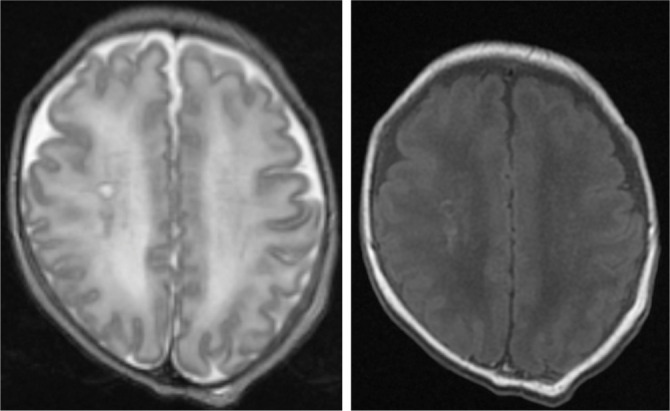

Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) revealed several and widespread areas of hypointensity of white matter in T2 sequences (hyperintensity in T1 images, Fig. 2), as possible outcomes of cerebral hypoxia or CMV infection.

Figure 2.

Brain MRI showing hypointensity of white matter in T2 sequences (left) and hyperintensity in T1 images (right) as possible outcomes of cerebral hypoxia or CMV infection.

After the introduction of the antiviral therapy and conventional thyroid replacement treatment, clinical conditions of the baby improved progressively. She was discharged at two months of corrected age, with close auxological and neurological follow-up and for all cCMV-related consequences. The one-year follow-up indicates good height and weight growth, moderate hypotonia, not associated with other serious neurological outcomes or neuro-psychomotor retardation.

Case presentation 2

A preterm male newborn (Gestational Age 32 w+ 2), small for gestational age (SGA) with very low birth weight (VLBW) (1330 g) was delivered by caesarean section (CS) for foetal distress. Family history was silent and pregnancy history revealed an intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) reported in the last ultrasound evaluation and maternal cytomegalovirus (CMV) serological conversion in the first trimester of gestation.

The baby was admitted at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) presenting poor clinical condition, jaundice with several petechiae, hepatosplenomegaly and mild respiratory distress.

Congenital CMV infection was confirmed by viral load > 5.000.000 CMV DNA copies/mL in urine and by 335200 copies/mL in plasma. Antiviral therapy with intravenous gancyclovir was started, switched to oral valgancyclovir after 6 weeks.

Biochemical investigations confirmed liver impairment with (GOT 278 UI/L and GPT 317 UI/L), high total bilirubin levels (5.4 mg/dL), and direct bilirubin 4.4 mg/dL for which treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was started, and low platelets count, with spontaneous resolution.

Audiometric evaluation with auditory brainstem response (ABR) revealed pathological patterns with severe bilateral sensineural hearing loss at subsequent follow-up. External hearing aid implant was placed with programmed cochlear implant at one-year of age.

Ophthalmologic examination was normal and brain MRI did not demonstrate any outcomes related to CMV infection.

In the meantime, the Neonatal Screening Center indicated high TSH levels at the first and second routine screening tests on DBS. Biochemical investigations have confirmed the condition of congenital hypothyroidism, with elevated TSH blood concentration (TSH 84 mUI/L) and low free T4 levels (9.8 pmol/L), in presence of negative thyroid antibodies.

Iodine131 thyroid scan showed normal morphology, volume and tracer uptake of the thyroid gland.

Treatment with oral solid levothyroxine was started at a dose of 10.5 mcg/kg/day. Biochemical investigation after initiation of treatment revealed an improvement in thyroid hormone levels (TSH 8.34 mUI/L, fT4 13.6 pmol/L) with subsequent normalization of thyroid hormones profile after the dose adjustment (TSH 0.5 mUI/L, fT4 18.2 pg/mL, fT3 4.3 pg/mL). After two years and six months of follow-up the clinical condition are good, the growth rate is adequate and the thyroid hormones profile is regular. The cochlear implant has been placed bilaterally and the neuro-psychomotor delay is under close follow-up.

Discussion

Primary congenital hypothyroidism is the most common congenital hormone deficiency, with increasing incidence in the last years (1-3). The defect in thyroid hormone biosynthesis or dyshormonogenesis also appears to have increased, from 10-15% to 40-50% of all cases (1-3). The most important reasons for the increase in the incidence of CH could be related to the decrease over time of the cut-off level of TSH in neonatal screening programs, the increase in the population at risk of CH such as premature babies and inadequate iodine supply. Premature babies are particularly at risk for permanent or transient hypothyroidism as they can present various thyroid dysfunctions associated with immaturity in the developmental of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, difficult adaptation to post-natal life, adverse effects of treatments administered in the perinatal period or consequences related to an inadequate iodine intake in pregnancy or in the perinatal period (2). The incidence of thyroid dysfunction among preterm infants is higher than term infants and has increased alongside to preterm survival for neonatal intensive care (2).

On the other hand, cCMV infection is also associated with preterm birth and severe neurological and neurodevelopmental sequelae; however, it appears to have a causal role for preterm birth, unlike CH which appears to be a consequent condition (6-9).

Incidence of congenital hypothyroidism has increased in the Italian region of Piedmont in the years 2014-2019 from 1:2000-4000 to 1:1090 (10). Over this period 165 newborns with congenital hypothyroidism were diagnosed of which two had congenital CMV diagnosis. If we consider the newborns population of our region in the period 2014-2019 the incidence of cCMV infection has increased in the babies with diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism (12/1000 vs. 5-7/1000 in the newborns without congenital hypothyroidism). This fact, together with the hypothesis of thyrocytes injury due to CMV intracellular action during the fetal period can be the basis for the assumption of the correlation between the two diseases. To our knowledge, no data on the association of cCMV infection with a CH condition have been reported in the literature to date. This suggestion has to be confirmed in larger cohorts by multicentre national and international studies, to rule out random association of these two congenital conditions.

Here, we report two cases of preterm infants (32 and 34 weeks of gestational age), with severe perinatal clinical conditions. Both newborns had cCMV infection with severe clinical manifestations. In the first case, brain MRI showed pathological signs classically associated with CMV infection, without audiometric alterations. In the second case, the viral infection resulted in severe bilateral sensineural hearing loss without apparent brain involvement at imaging.

Both presented congenital hypothyroidism, with initial difficult compensation of thyroid hormone metabolism but with important clinical improvement once thyroid hormone profile was brought into the normal range with conventional substitutive treatment. In the male with liver enzymes alteration, the solid form of levothyroxine was used instead of the liquid form that contains minimal quantities of ethanol.

In conclusion, currently very few data so far exist to confirm a possible causal role of cCMV in primary congenital hypothyroidism and further data or case reports are undoubtedly needed. However, the two cases described here could be useful to alert gynaecologists and paediatricians in case of known maternal CMV seroconversion to assess the presence of an adequate maternal thyroid hormone profile during pregnancy and avoid maternal and foetal hypothyroidism. In case of alteration, the neonatologist should be promptly informed to investigate the presence of hypothyroidism at birth and start replacement treatment as soon as possible.

On the other hand, in case of first diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism, when the clinical condition of the newborn do not readily improve after the substitutive treatment and are associated with serious clinical conditions that suggest a congenital infection, it might be important to consider a potential cCMV infection, to be confirmed searching for the virus in urine or saliva, especially in the case of preterm birth.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Peters C, van Trotsenburg ASP, Schoenmakers N. Congenital hypothyroidism: update and perspectives. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;179(6):R297–317. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigone MC, Caiulo S, Di Frenna M, Ghirardello S, Corbetta C, Mosca F, Weber G. Evolution of thyroid function in preterm infants detected by screening for congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lain S, Trumpff C, Grosse SD, Olivieri A, Van Vliet G. Are lower TSH cutoffs in neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism warranted? Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(5):D1–D12. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempers MJ, Ozgen HM, Vulsma T, Merks JH, Zwinderman KH, de Vijlder JJ, Hennekam RC. Morphological abnormalities in children with thyroidal congenital hypothyroidism. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:943–951. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreissner E, Neto EC, Gross JL. High prevalence of extrathyroid malformations in a cohort of Brazilian patients with permanent primary congenital hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2005;15:165–169. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivieri A, Stazi MA, Mastroiacovo P, Fazzini C, Medda E, Spagnolo A, De Angelis S, Grandolfo ME, Taruscio D, Cordeddu V, Sorcini M. Study Group for Congenital Hypothyroidism. A population-based study on the frequency of additional congenital malformations in infants with congenital hypothyroidism: data from the Italian Registry for Congenital Hypothyroidism (1991-1998) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:557–562. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leruez-Ville M, Foulon I, Pass R, Ville Y. Cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy: State of the science. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:330–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich ML, Schieffelin JR. Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection. Ochsner J. 2019;19:123–130. doi: 10.31486/toj.18.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler KB, Boppana SB. Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection. Semin Perinat. 2018;42:149–154. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]