Abstract

Constitutively activated G proteins caused by specific mutations mediate the development of multiple malignancies. The mutated Gαq/11 are perceived as oncogenic drivers in the vast majority of uveal melanoma (UM) cases, making directly targeting Gαq/11 to be a promising strategy for combating UM. Herein, we report the optimization of imidazopiperazine derivatives as Gαq/11 inhibitors, and identified GQ262 with improved Gαq/11 inhibitory activity and drug-like properties. GQ262 efficiently blocked UM cell proliferation and migration in vitro. Analysis of the apoptosis-related proteins, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and yes-associated protein (YAP) demonstrated that GQ262 distinctly induced UM cells apoptosis and disrupted the downstream effectors by targeting Gαq/11 directly. Significantly, GQ262 showed outstanding antitumor efficacy in vivo with good safety at the testing dose. Collectively, our findings along with the favorable pharmacokinetics of GQ262 revealed that directly targeting Gαq/11 may be an efficient strategy against uveal melanoma.

Key words: G proteins, Gαq/11 inhibitors, SARs, BRET, Uveal melanoma, Antitumor, Safety, Pharmacokinetics

Graphical abstract

Constitutively activated Gαq/11 proteins drive the vast majority of uveal melanoma (UM). GQ262 effectively combats UM both in vitro and in vivo by targeting Gαq/11 directly.

1. Introduction

Heterotrimeric G proteins are the families of guanine nucleotide-binding proteins. The involvement of G proteins in transmembrane signal transduction was first discovered approximately 40 years ago1. Heterotrimeric G proteins consist of 3 non-identical subunits (α, β, and γ) in the order of diminishing mass1,2. In mammals, 21 different Gα subunits encoded by 16 genes, 6 different Gβ subunits encoded by 5 genes, and 12 different Gγ subunits encoded by 12 genes have been identified3, 4, 5. G proteins are characteristically categorized into Gαs, Gαi, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13 with regard to the sequence similarity of Gα subunits6. The downstream effectors coupled to individual Gα subunits are also distinct: (i) Gαs stimulates adenylyl cyclase (AC), which synthesizes the cAMP from ATP7; (ii) Gαi suppresses AC, which controls the intracellular cAMP levels8; (iii) Gαq/11 activate phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ), which generates diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol triphosphate (IP3)9, 10, 11; and (iv) Gα12/13, which are identified to directly interact with guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the GTPase Rho (RhoGEF) and induce the activation of Rho2,5,12, 13, 14.

G proteins, which in general are perceived as molecular switches, mediate signal transduction connecting the heptahelical G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) with various intracellular effectors2,15. Different from the transmembrane GPCRs, G proteins are situated in cells. The processes of signal transduction are initiated by extracellular stimuli binding to GPCRs, which induce the conformational change of GPCRs and activate G proteins4. Consequently, the G proteins cycle is triggered to further transmit the signals2,16. The signaling cycle could be interrupted by the mutation or covalent modification of Gα subunits17. Under certain circumstances, the intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα is blocked, which retains the Gα in a “switch-on” state and persistently activates the complicated downstream signaling networks18,19.

Of note, G proteins are served as the crucial nodes on the canonical GPCRs/G proteins/effectors axis, and involved in extensive human pathological and physiological processes20, 21, 22, 23. In 2010, mutated Gαq (encoded by GNAQ) and Gα11 (encoded by GNA11) were unveiled to be associated with uveal melanoma (UM)20,24, 25, 26. The mutated G proteins impair the GTP hydrolysis and prolong the signaling activity27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33. The hotspots of Gαq/11 mutations flock around two residues, Q209 and R183. Hence, Gαq/11 harboring Q209 or R183 mutations are recognized as oncogenic drivers in the vast majority of UM cases27. Over the past decade, enormous efforts for UM treatment were devoted to regulate the complex downstream signaling of Gαq/11, including two key nodes MAPK and ERK34, 35, 36. Unfortunately, targeting either of the nodes did not exhibit satisfied therapeutic outcome in UM clinical trials37, 38, 39, 40. A presumable explanation is that Gαq/11 could activate multiple and independent downstream signaling pathways, targeting a specific node could not achieve the optimal therapeutic results41. Thus, directly targeting the constitutively activated Gαq/11 maybe represent one potential application to overcome UM.

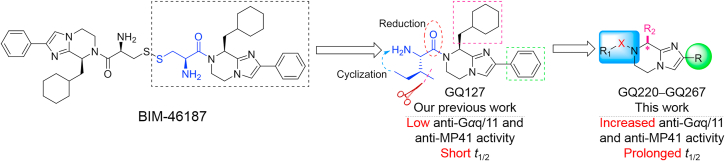

Up to now, very few reported Gαq/11 inhibitors are shown in Fig. 1, including YM-254890 (1)42, FR900359 (2)43, BIM-46187 (3)44, and GQ127 (4)45. The cyclic depsipeptide YM-254890 (1) powerfully inhibits Gαq/11 with the IC50 value of 95 nmol/L on CHO cells that stably express the M1 muscarinic receptor42. Analysis of the Gαqβγ/YM-254890 crystal structure demonstrated that 1 blocks the GDP/GTP exchange through suppressing the GDP release46. FR900359 (2), which possesses subtle structural differences with YM-254890, exhibits inhibitory potency to Gαq/11 in low nanomolar range (IC50 = 32 nmol/L) and shares the same mode of action (MOA) with 142,47. Although 1 and 2 showed exciting bioactivity, the development of these two compounds is immensely restricted due to the low abundance in nature and synthetic complexity. BIM-46187 (3) was reported as a small molecular Gαq/11 inhibitor in 201448. 3 permits the GDP exit but prevents GTP entry, which is the possible mechanism of how 3 inhibits Gαq/1148. However, the large molecular weight and high toxicity of 3 complicate its development. Recently, our group performed structural optimization towards 3 with the purpose of improving the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency, simplifying the structure, and reducing the toxicity. The small molecule GQ127 (4) was obtained as an effective Gαq/11 inhibitor in vitro and in vivo without obvious toxicity, in comparison with 345. Nevertheless, the electron-rich primary amine within 4 might be the issue for metabolic and oxidative stability, the relatively short elimination half-life (t1/2 = 1.2 h) and unsatisfactory Gαq/11 inhibitory potency encouraged us to pursue new small molecules with improved inhibitory potency and drug-like properties45. In this study, we performed structural optimization on compound 4 and successfully obtained GQ262 which showed improved Gαq/11 inhibitory potency. Moreover, the antitumor efficacy and mechanism of GQ262 were explored. The obtained data served as solid evidences for the good antitumor activity of GQ262 both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1.

Structure of reported Gαq/11 inhibitors.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthetic design

In our previous study, we developed compound 4 as a new Gαq/11 inhibitor by the structural optimization of 345. However, the Gαq/11 inhibitory activity, antitumor efficacy, and druggability of 4 are not satisfied. To further develop novel and potent Gαq/11 inhibitors with good druggability, our optimization began with modifying the phenyl group of 4 (Fig. 2). Based on the application of bioisosterism in drug discovery, we utilized different aromatic heterocycles to replace the phenyl group. We also substituted the aromatic heterocycles with alkyls, cycloalkyls, and heterocycloalkyls to investigate the necessity of the rigid structure. When analyzing the structural characteristics of 4, we speculated that whether the flexibility of the amino acid fragment is related to the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency. Thus, the carbonyl group was reduced to increase the flexibility to explore the relationships between the flexibility and efficacy. In addition, the cyclohexylmethyl group was replaced by other alkyl groups to further investigate the structure–activity relationships (SARs), by combining with the results of augmenting efficacy in our studies45. Ultimately, GQ220‒GQ267 were synthesized for further evaluation of inhibitory effects on Gαq/11 and UM cells.

Figure 2.

Design and structural optimization strategies for GQ220‒GQ267. The phenyl group (green) is modified to discuss the necessity of the rigid structure. Reduction of the carbonyl (red) and cyclization of the head fragment (blue) are to improve the potency and drug-like property. Replacing the cyclohexylmethyl fragment (pink) is to investigate the significance for inhibitory activity.

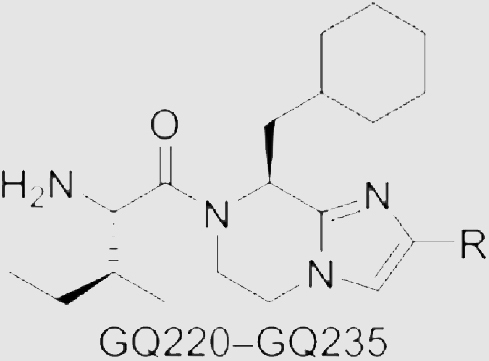

2.2. Chemistry

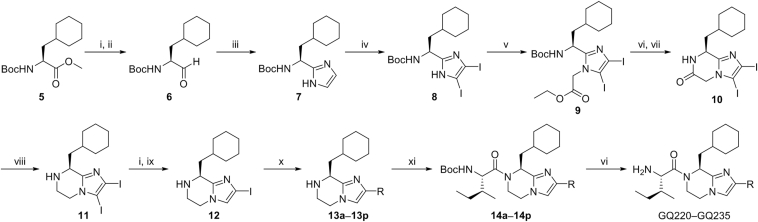

GQ220‒GQ235 were prepared according to the synthetic route depicted in Scheme 1. The synthesis of imidazopyrazine analogs began with the commercially available N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-l-cyclohexylalanine methyl ester 5 which was treated with sodium borohydride in tetrahydrofuran (THF)/methanol, followed by treating with Dess-Martin periodinane to give intermediate 6 in 75% yield. 7 was obtained from 6 by Debus–Radziszewski reaction. Treating 7 with iodine and potassium hydroxide in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) gave 8. Then, nucleophilic substitution between 8 and ethyl bromoacetate was performed to deliver 9. Deprotection and intramolecular lactamization of 9 gave 10, followed by reducing the amide group by borane to give building block 11. Removing the iodine by treating 11 with sodium borohydride in methanol/THF resulted in 12. The key building blocks 13a‒13p were prepared from 12 by Suzuki reaction. Finally, compounds GQ220‒GQ235 were furnished by the condensation of N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-l-isoleucine with 13a‒13p and removing the protecting groups.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of GQ220‒GQ235. Reagents and conditions: (i) NaBH4, methanol, ice-bath; (ii) DMP, DCM, ice-bath; (iii) glyoxal, NH3/H2O, methanol, rt; (iv) I2, KOH, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), rt; (v) ethyl bromoacetate, K2CO3, DMF, rt; (vi) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), DCM, rt; (vii) K2CO3, DCM/methanol, rt; (viii) BH3·THF, THF, reflux; (ix) HCl, methanol, reflux; (x) Pd (dppf)Cl2, K3PO4, DMF/H2O, 90 °C, Ar; (xi) HATU, DIPEA, DMF, rt.

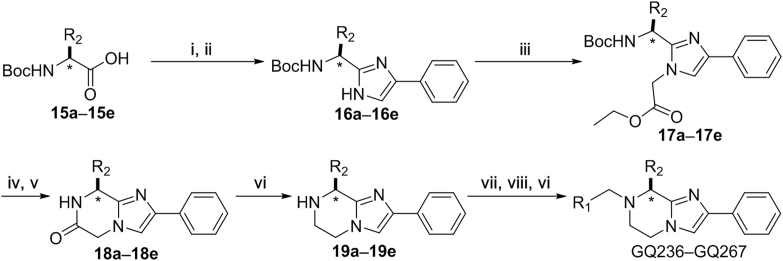

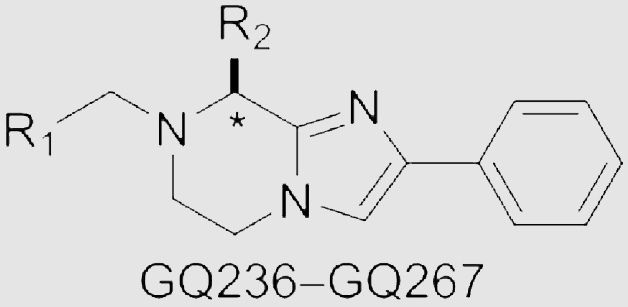

The synthesis of imidazopyrazine analogs GQ236‒GQ267 started from N-Boc-protected amino acids 15a‒15e (Scheme 2). Treating 15a‒15e with cesium carbonate in DMF containing 2-bromoacetophenone. Then, the mixtures were treated with ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) to obtain 16a‒16e. Treating 16a‒16e with ethyl bromoacetate to obtain intermediates 17a‒17e by the nucleophilic substitutions. Deprotection and intramolecular lactamization of 17a‒17e were performed to prepare 18a‒18e. Building blocks 19a‒19e were furnished by reducing the amide groups. Successively, condensation of 19a‒19e with amino acids, deprotection and reducing with borane delivered GQ236‒GQ267. In total, 48 new imidazopyrazine derivatives were prepared.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of GQ236‒GQ267. Reagents and conditions: (i) 2-bromoacetophenone, Cs2CO3, DMF, rt; (ii) NH4OAc, toluene, reflux; (iii) K2CO3, DMF, rt; (iv) TFA, DCM, 25 °C; (v) K2CO3, CH2Cl2/methanol, rt; (vi) BH3·THF, THF, reflux; (vii) HATU, DIPEA, DMF, rt; (viii) TFA, (i-Pr)3SiH, rt, Ar.

2.3. Structure–activity relationship studies

Inositol monophosphate (IP1) accumulation assay was utilized to characterize Gαq/11 inhibitory activity on CHO-M1 cells, which applied homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF). In vitro antiproliferative potency was evaluated on UM cell lines MP41 with GNA11Q209L mutation and 92.1 with GNAQQ209L mutation by CCK-8 assay. Table 1, Table 2 summarized the results.

Table 1.

Gαq/11 inhibitory activity and antitumor activity of GQ220‒GQ235a.

| Compd. | R | IP1 inhibition at 10 μmol/L | Antiproliferation (IC50, μmol/L) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP41 | 92.1 | |||

| GQ220 |  |

20.8 ± 1.1% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ221 |  |

20.0 ± 0.6% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ222 |  |

27.0 ± 5.2% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ223 |  |

16.6 ± 1.2% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ224 |  |

31.5 ± 6.0% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ225 |  |

28.7 ± 1.6% | 25.3 ± 0.9 | 18.8 ± 1.7 |

| GQ226 |  |

29.5 ± 3.0% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ227 |  |

18.4 ± 0.9% | 21.2 ± 0.5 | 21.6 ± 0.6 |

| GQ228 |  |

24.8 ± 1.5% | 11.0 ± 0.1 | 19.0 ± 0.6 |

| GQ229 |  |

15.8 ± 1.8% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ230 |  |

13.7 ± 0.6% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ231 |  |

20.6 ± 2.1% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ232 |  |

10.9 ± 0.7% | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 16.1 ± 1.0 |

| GQ233 |  |

22.2 ± 1.9% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ234 |  |

10.8 ± 1.4% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ235 |  |

22.3 ± 1.3% | > 40 | > 40 |

| 3 | 26.9 ± 3.3% | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | |

IP1 accumulation assay was utilized to characterize Gαq/11 inhibitory activity. Antitumor activity was measured utilizing CCK-8 assay. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Table 2.

Gαq/11 inhibitory activity and antitumor activity of GQ236‒GQ267a.

| Compd. | R1 | R2 (∗) | IP1 inhibition at 10 μmol/L | Antiproliferation (IC50, μmol/L) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP41 | 92.1 | ||||

| GQ236 |  |

|

48.4 ± 2.4% | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 9.3 ± 0.5 |

| GQ237 |  |

|

43.0 ± 3.3% | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 0.1 |

| GQ238 |  |

|

34.4 ± 1.7% | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 7.3 ± 0.7 |

| GQ239 |  |

|

50.2 ± 5.2% | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 11.6 ± 0.6 |

| GQ240 |  |

22.5 ± 4.2% | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.6 | |

| GQ241 |  |

|

31.3 ± 9.0% | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.2 |

| GQ242 |  |

|

41.0 ± 6.0% | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.4 |

| GQ243 |  |

|

41.6 ± 5.8% | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 9.6 ± 0.7 |

| GQ244 |  |

|

45.8 ± 10.5% | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 1.3 |

| GQ245 |  |

|

46.8 ± 8.6% | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

| GQ246 |  |

|

40.4 ± 7.0% | 14.9 ± 0.8 | 15.8 ± 1.0 |

| GQ247 |  |

|

44.5 ± 3.4% | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 |

| GQ248 |  |

|

49.7 ± 9.5% | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 10.9 ± 0.5 |

| GQ249 |  |

|

44.1 ± 3.0% | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 11.4 ± 0.3 |

| GQ250 |  |

|

41.8 ± 2.7% | 6.9 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 0.2 |

| GQ251 |  |

|

51.2 ± 4.9% | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 12.6 ± 0.7 |

| GQ252 |  |

|

35.9 ± 7.3% | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.3 |

| GQ253 |  |

|

32.4 ± 1.0% | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 0.4 |

| GQ254 |  |

|

44.2 ± 0.3% | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 11.2 ± 0.7 |

| GQ255 |  |

|

27.7 ± 6.7% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ256 |  |

|

47.6 ± 5.0% | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 8.7 ± 0.7 |

| GQ257 |  |

|

33.2 ± 1.3% | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.5 |

| GQ258 |  |

|

48.3 ± 6.5% | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 11.6 ± 1.4 |

| GQ259 |  |

|

36.3 ± 0.9% | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 10.7 ± 0.8 |

| GQ260 |  |

|

53.4 ± 7.0% | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 11.6 ± 1.2 |

| GQ261 |  |

|

27.0 ± 5.1% | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 0.5 |

| GQ262 |  |

|

57.2 ± 1.9% | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.1 |

| GQ263 |  |

|

38.9 ± 3.3% | 10.5 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 0.5 |

| GQ264 |  |

|

5.9 ± 1.1% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ265 |  |

|

13.5 ± 0.5% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ266 |  |

|

17.5 ± 1.1% | > 40 | > 40 |

| GQ267 |  |

|

8.9 ± 0.8% | > 40 | > 40 |

| 3 | 26.9 ± 3.3% | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | ||

IP1 accumulation assay was utilized to characterize Gαq/11 inhibitory activity. Antitumor activity was measured utilizing CCK-8 assay. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

To augment the efficacy of compounds on Gαq/11 inhibition and tumor suppression, GQ220‒GQ226 with aromatic heterocycles replacing the phenyl group of 4 were designed and synthesized using the concept of bioisosterism, as the SAR of the phenyl ring has never been carefully explored. As shown in Table 1, GQ220, GQ221 and GQ223 showed reduced activity on inhibiting Gαq/11 and UM cell lines. GQ222 and GQ224‒GQ226 showed improved Gαq/11 inhibitory potency, but reduced activity on suppressing MP41 and 92.1 cell lines. Alkyls, cycloalkyls and heterocycloalkyls were also introduced with the purpose of providing flexibility for the molecules, and compounds GQ227‒GQ235 were prepared and characterized (Table 1). However, most of the alkyl substituted compounds either suffered from losing Gαq/11 inhibitory potency, or showed weak antiproliferative ability towards MP41 and 92.1 cell lines, suggesting that the aromatic substitution is essential for maintaining the activity.

The amino acid fragment in 4 was proven to be essential for keeping the Gαq/11 inhibitory activity and reducing the cellular toxicity, we speculated whether increasing the molecular flexibility by reducing the amide group to tertiary amine could contribute to the inhibitory potency. Interestingly, reducing the amide group in 4 led to analog GQ236, which exhibited remarkable improvement both in inhibiting Gαq/11 and suppressing the proliferation of MP41 and 92.1 cells. The exciting results encouraged us to further explore the side chain of the amino acid part. Considering the natural and some unnatural amino acids with side chain diversity are abundant and easily available building blocks, we chose four natural and five unnatural amino acids with different alkyl branched chains and prepared GQ237‒GQ245. As shown in Table 2, most compounds displayed improved Gαq/11 inhibitory activity at the concentration of 10 μmol/L in comparison to 3, except for GQ240 and GQ241. It is worth noting that the antiproliferative activity of these compounds on UM cells were also enhanced or maintained. Encouraged by these results, other natural amino acids with different side chains were employed to obtain GQ246‒GQ259. Of note, all these compounds exhibited favorable Gαq/11 inhibitory activity (Table 2). Particularly, GQ248 and GQ251 showed better Gαq/11 inhibitory activity than 3 at 10 μmol/L. Similarly, most of the compounds potently inhibited the growth of MP41 or 92.1 cells at low micromolar concentrations in vitro, except for GQ248 and GQ251 showed uncompetitive efficacy in combating UM cell lines in comparison with 3. The results unveiled that releasing the restricted conformation of the carbonyl group is beneficial for increasing the Gαq/11 and tumor inhibitory efficacy.

Of interest, proline which possesses a specific pyrrolidine segment among the natural amino acids was introduced into GQ260. As depicted in Table 2, GQ260 inhibited Gαq/11 with 53.4 ± 7.0% inhibition at 10 μmol/L, and suppressed MP41 and 92.1 cells proliferation with the IC50 values of 6.7 ± 0.6 μmol/L and 11.6 ± 1.2 μmol/L. (S)-Piperidine-2-carboxylic acid containing the piperidine fragment, which is perceived as a bioisostere of pyrrolidine, was also introduced to prepare GQ261. Compared to GQ260, the antiproliferative activity of GQ261 was retained, despite the decreased Gαq/11 inhibitory efficacy (Table 2). The results indicated that introducing the cyclic secondary amine motif into GQ260 and GQ261 could either improve the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency or enhance the antiproliferative activity of UM cells. Encouraged by these findings, and considering that the tertiary amine is potentially more metabolic and redox stable compared with the secondary amine, we thus further optimized the compounds by introducing a methyl group into the cyclic secondary amine, leading to analogs GQ262 and GQ263. To our delight, GQ262 potently inhibited Gαq/11 with 57.2 ± 1.9% suppression at 10 μmol/L, and disrupted MP41 cell proliferation with the IC50 of 5.1 ± 0.6 μmol/L (Table 2), suggesting that the cyclic tertiary amine motif is superior to secondary or primary amine.

Inspired by the above-mentioned SARs, we combined the prevogative R substituent phenyl group and R1 substituent 1-methylpyrrolidine with four different R2 substituents (Ref. 45) which were beneficial for Gαq/11 inhibitory potency (Table 2). GQ264‒GQ267 were designed and synthesized, but showed decreased inhibitory activity towards Gαq/11 and poor antitumor efficacy, compared with GQ262 (Table 2). These results indicated that the proper combination of the cyclohexylmethyl moiety with R substituent phenyl group and R1 substituent 1-methylpyrrolidine is essential for maintaining or improving the activity of compounds for combating Gαq/11 and UM cells.

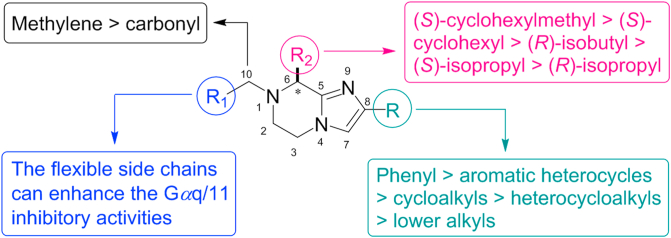

Hence, we summarized the SAR information of the synthesized imidazopyrazine derivatives in Fig. 3. The phenyl substituted R is important for maintaining the inhibitory activity towards Gαq/11 and UM cells. Increasing the molecular flexibility by reducing the amide to amine generally improves the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency and the anti-UM cell ability. Introducing the cyclic tertiary motif to R1 not only acquires better Gαq/11 inhibitory efficacy, but also provides the possibility for modulating the metabolic stability. Besides, the proper combination of the R1 and R2 is essential for maintaining the Gαq/11 inhibitory efficacy and anti-UM cell ability.

Figure 3.

Summary of structure–activity relationships of imidazopyrazine scaffold derivatives as Gαq/11 inhibitors.

2.4. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of GQ262

The previous study revealed that part of the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency of 3 is derived from its cytotoxicity, we thus investigated the cytotoxicity of the newly designed compound GQ262 by treating the CHO-M1 cells at different concentrations, and characterized the cell viability using CCK-8 assay. As shown in Fig. 4, 3 obviously inhibited the cell proliferation at the concentrations of 10 and 20 μmol/L in 2 h, but GQ262 did not impact the cell viability at indicated concentrations in 2 h, even when the concentration up to 20 μmol/L for 24 h (Fig. 4), indicating that GQ262 has satisfactory safety towards normal cells.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of GQ262. (A) Cell viability after pre-treating with 3 and GQ262 for 2 h. (B) Cell viability after pre-treating with 3 and GQ262 for 24 h. Bar is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

2.5. Effects of GQ262 on agonist-induced BRET signals and Ca2+ release

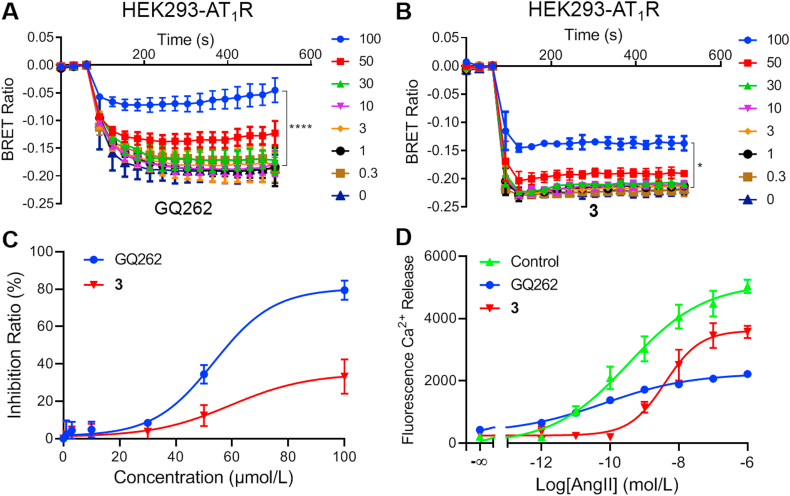

To verify that GQ262 could trap Gαq/11 directly, we transfected AT1R, Gαq-RLuc8, unlabeled Gβ1, and Gγ2-Venus in HEK293 cells which were applied to determine the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) alteration and Ca2+ release. Pretreating HEK293-AT1R cells with 3 and GQ262 at different concentrations, followed by measuring the variable BRET signals between Gα and Gβγ. As depicted in Fig. 5A‒C, GQ262 displayed dose-dependently inhibitory efficacy on BRET signals. Also, the agonist-mediated Ca2+ release was employed to evaluate the effects of GQ262 on blocking Gαq/11. When AngII binds to AT1R, the activated AT1R initiates Gαq/11, which intertwines and activates PLCβ. As a consequence, Ca2+ release is accelerated. We pretreated 3 and GQ262 with HEK293-AT1R cells at 100 μmol/L, and assessed the agonist-stimulated Ca2+ release at different concentrations of AngII. As expected, GQ262 obviously suppressed the Ca2+ release (Fig. 5D). All these results indicated that GQ262 directly acts on Gαq/11.

Figure 5.

Effects of 3 and GQ262 on the BRET signal alterations and Ca2+ release stimulated by agonist. (A) and (B) BRET signals were assessed after adding AngII. (C) The dose–response curves of 3 and GQ262 on AT1R-activated BRET changes after adding AngII. (D) The dose–response curve of AngII-induced Ca2+ release was determined in the presence of 3 or GQ262 at 100 μmol/L. Data is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 vs control; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

2.6. GQ262 inhibits the proliferation of UM cells by targeting Gαq/11

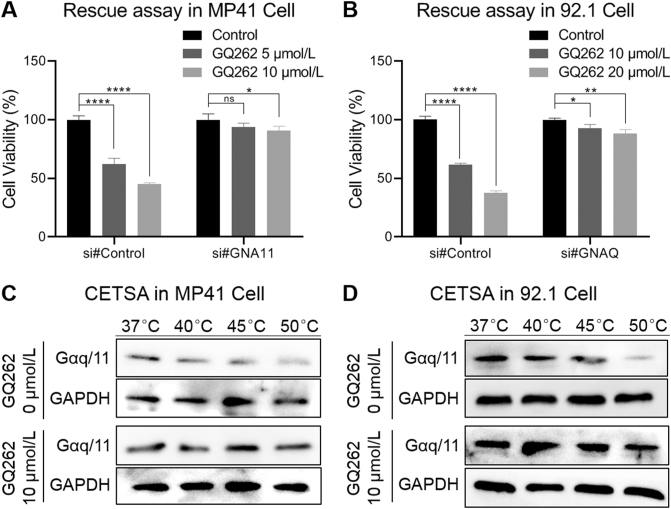

To further validate that GQ262 suppresses UM cell proliferation through directly targeting Gαq/11, we transfected the siRNA targeting GNA11 in MP41 cells and GNAQ in 92.1 cells to knock down the GNAQ/11 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Then, we pre-treated the cells with GQ262. As depicted in Fig. 6A, GQ262 exhibited remarkable antiproliferative activity on MP41 (si#control) at 5 and 10 μmol/L, respectively. However, GQ262 could not inhibit MP41 cell proliferation (si#GNA11). Similarly, GQ262 had no inhibitory effect on proliferation of GNAQ knockdown 92.1 cells at 10 and 20 μmol/L (Fig. 6B), suggesting the antiproliferative potency of GQ262 on UM cells is achieved by blocking Gαq/11. In addition, the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) was employed to study whether GQ262 binds to Gαq/11 straightforwardly. As expected, the thermal denaturation temperature of Gαq/11 increased from 37 to 50 °C after the incubation of the cell lysates with GQ262 (Fig. 6C and D, Supporting Information Fig. S2), and the melting temperature was increased by 10 °C, indicating that GQ262 indeed binds to Gαq/11. Taken together, these data demonstrated that GQ262 directly binds to Gαq/11.

Figure 6.

Rescue assay and cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA). (A) MP41 cell viability of GQ262 at different concentrations for 72 h. (B) 92.1 cell viability of GQ262 at different concentrations for 72 h. (C) GQ262 enhanced the thermal stability of Gαq/11 from 37 to 50 °C in MP41 cells. (D) GQ262 enhanced the thermal stability of Gαq/11 from 37 to 50 °C in 92.1 cells. Data is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 vs control; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

2.7. GQ262 induces UM cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

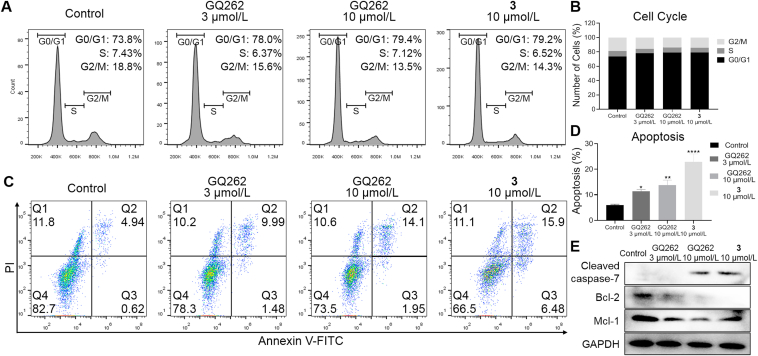

To investigate the mechanism of GQ262 inhibiting UM cell proliferation, we performed the cell cycle analysis utilizing flow cytometry. As depicted in Fig. 7A and B, the cellular proportion elevated from 73.8% to 78.0% and 79.4% in G0/G1 phase after separately incubating MP41 cells with GQ262 at 3 and 10 μmol/L, and the cellular proportion in S and G2/M phases was clearly decreased. In agreement with MP41 cells, 92.1 cells were incubated with GQ262 at 10 and 20 μmol/L, the cellular proportion elevated from 70.1% to 77.1% and 83.5% in G0/G1 phase (Supporting Information Fig. S3). These results demonstrated that GQ262 significantly disrupts the cell cycle of MP41 and 92.1 cells at G0/G1 phase.

Figure 7.

Cell cycle distributions and apoptotic effects of 3 and GQ262 in UM cells. (A) and (B) MP41 cell cycle distributions were measured via flow cytometer after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 48 h. (C) and (D) Apoptotic MP41 cells were determined after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 48 h. (E) Analysis of cleaved caspase-7, Bcl-2, and Mcl-1 levels in UM cells. Data is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 vs control; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

To obtain further insight into the antitumor mechanism of GQ262, we conducted an apoptosis assay utilizing flow cytometer. As depicted in Fig. 7C and D, GQ262 promoted the cell apoptosis which were 11.5% (3 μmol/L) and 16.0% (10 μmol/L), while 3 displayed the apoptotic value of 22.4% at 10 μmol/L. The cellular proportion augmented with the increasing concentrations of GQ262. Similarly, GQ262 effectively induced the apoptosis of 92.1 cells with the apoptotic rates of 9.34% (10 μmol/L) and 17.5% (20 μmol/L). In addition, we assessed the apoptosis related proteins, such as cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase-7 (caspase-7), Bcl-2, and Mcl-1. As expected, GQ262 promoted the up-regulation of cleaved caspase-7 and down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 (Fig. 7E, Supporting Information Fig. S4). These results suggested that GQ262 dose-dependently induces the UM cell apoptosis.

2.8. GQ262 suppresses UM colony formation

To better comprehend the antitumor capacity of GQ262, the colony survival assay was conducted to investigate the inhibition of clonogenicity on UM cell lines MP41 and 92.1 (Fig. 8). Corresponding to the antiproliferative potency, GQ262 obviously blocked the colony formation of MP41 and 92.1 cells at 1 and 3 μmol/L. The data indicated that GQ262 has effectual antitumor activity on UM.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of colony formation of GQ262. (A) Photos of MP41 cell colony formation (magnification, × 40). (B) Numbers of colony formation were counted via Colony-Counter after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 9 days. (C) Photos of 92.1 cell colony formation (magnification, × 40). (D) Numbers of colony formation were counted via Colony-Counter after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 9 days. Data is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 vs control.

2.9. GQ262 suppresses UM migration and invasion

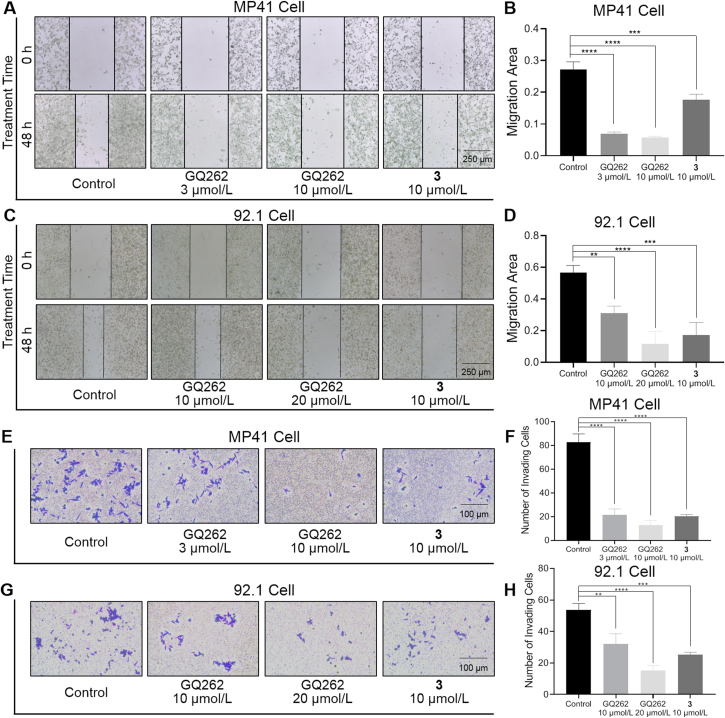

UM cells have strong metastatic characteristics, which drive the invasion towards the distant organs36. Gαq/11 signaling is involved in UM cell migration, and suppressing Gαq/11 could eliminate the migratory and invasive capacities of UM cells36. To verify whether GQ262 could inhibit the cell migration and invasion, Boyden chamber Transwell experiment was performed on UM cells. As depicted in Fig. 9A‒D, MP41 and 92.1 cells showed aggressive migration in the absence of GQ262. To our delight, GQ262 remarkably and dose-dependently inhibited the MP41 and 92.1 migration at 3, 10, and 20 μmol/L, compared to 3. In agreement with the effects on suppressing the migration, MP41 and 92.1 cells incubated with GQ262 exhibited poor invasion at 3, 10, and 20 μmol/L (Fig. 9E‒H). Overall, the results revealed that GQ262 suppresses UM migration and invasion via blocking Gαq/11.

Figure 9.

Migrative and invasive inhibition of GQ262 on UM cells. (A) Photos of MP41 cell migration (magnification, × 40). (B) Quantitation of cell migration after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 48 h. (C) Photos of 92.1 cell migration (magnification, × 40). (D) Quantitation of cell migration after incubating with 3 or GQ262 for 48 h. (E) Photos of MP41 cell invasion (magnification, × 100). (F) Quantitation of invading cells. (G) Photos of 92.1 cell invasion (magnification, × 100). (H) Quantitation of invading cells. Data is reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗∗P < 0.01 vs control; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

2.10. Metabolic stability of GQ262

Given the effective anticancer potency of GQ262 in vitro, we evaluated the metabolic stability of GQ262 in liver microsomes of human in vitro. As depicted in Table 3, GQ262 displayed moderate metabolic stability with the half-time (t1/2) of 57.5 min and the intrinsic clearance (CLint) of 30.2 mL/min/kg, indicating that GQ262 possesses moderate in vitro metabolic stability and drug-like properties, which needs to be further optimized before clinical applications.

Table 3.

Metabolic stability parameters of GQ262 in liver microsomes.

Half-life.

Intrinsic clearance.

2.11. Anti-UM efficacy of GQ262 in vivo

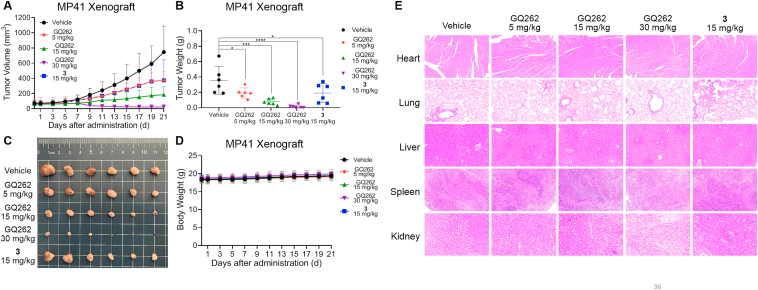

Encouraged by the promising in vitro antitumor activity, we conducted MP41 xenograft model to further assess the in vivo anti-UM potency of GQ262. We administrated the nude BALB/cnu/nu mice bearing tumor with GQ262 for 21 days. The doses were 5, 15, and 30 mg/kg/day. We determined the tumor volume every two days, as well as the body weight. To our delight, tumor growth inhibition (TGI) of GQ262 was up to 106.6% at 30 mg/kg (Fig. 10A and B, Supporting Information Fig. S5). Meanwhile, GQ262 exhibited robust anticancer activity (TGI = 82.8%, 15 mg/kg), in sharp contrast to 3 (TGI = 55.3%, 15 mg/kg). GQ262 also displayed effectual tumor inhibitory potency at 5 mg/kg (TGI = 55.2%, Fig. 10A and B), demonstrating that GQ262 is highly potent for combating MP41 xenograft model. Importantly, body weight of the mice did not decline (Fig. 10D) and we did not observe manifest side effects during and after the treatment (Fig. 10E, Supporting Information Fig. S6). All these results strongly supported our hypothesis that directly inhibiting constitutively activated Gαq/11 is a powerful and effective approach for treating UM, other than inhibiting a specific node in the downstream signaling pathways.

Figure 10.

Anti-UM efficacy of GQ262 in vivo. Mice were administered with 3 and GQ262 via intraperitoneal injection (ip) for 21 days (n = 6). (A) Tumor volume. (B) Tumor weight. (C) Photo of tumor tissue. (D) Body weight. (E) H&E staining. ∗P < 0.05 vs vehicle; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

2.12. GQ262 modulates ERK and YAP by targeting Gαq/11

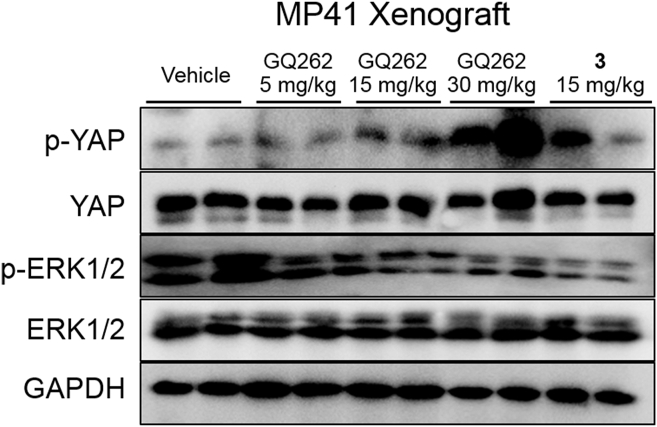

ERK is a canonical effector in Gαq/11-PLCβ signaling pathway, and participates in complex process of cell mitosis after phosphorylation17, 18, 19. Inhibiting Gαq/11 could block the phosphorylation of ERK, which then suppresses the growth of UM. To verify the effects of GQ262 on suppressing the ERK phosphorylation, we evaluated the expression level of phosphorylated ERK in MP41 xenograft tumor tissues (Fig. 11, Supporting Information Fig. S7). As expected, GQ262 indeed inhibited the phosphorylated ERK in tumor tissues at the testing dose.

Figure 11.

Effects of 3 and GQ262 on modulating the Gαq/11 downstream signaling effectors in MP41 xenograft (n = 6). Expression of targeted proteins (ERK, p-ERK, YAP, and p-YAP) was analyzed utilizing Western blot.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) is another primary mediator for tumorigenesis, and contributes to the development of UM22. Dephosphorylation of YAP is initiated by the activated Gαq/11, which promotes the proliferation of UM. Thereby, the phosphorylated YAP expression was determined in MP41 xenograft tumor tissues (Fig. 11). As expected, GQ262 increased the accumulation of phosphorylated YAP at the testing dose.

Altogether, these results unveiled that GQ262 effectively inhibits the downstream signaling networks of Gαq/11 by targeting Gαq/11 in UM.

2.13. Pharmacokinetic (PK) studies of GQ262

To better comprehend the druggability of GQ262, the male ICR mice were employed to assess the PK properties. The dose of intravenous injection (iv) was 5 mg/kg, and the dose of oral administration (po) was 15 mg/kg. In comparison to 4 with short t1/2 (1.2 h)45, GQ262 showed increased elimination t1/2 with the value of 1.8 h (Table 4). As shown in Table 4, GQ262 attained the AUC0‒t of 1625 h·ng/mL with Cmax of 2471 ng/mL via iv. Also, GQ262 was rapidly distributed into tissue, with Vss value of 3.9 L/kg, and showed the CL of 50.2 mL/min/kg following iv administration in mice. Besides, GQ262 given orally at 15 mg/kg exhibited favorable oral bioavailability (F) of 59.5% and the mean residence time (MRT0‒t) was 3.1 h (Table 4, Supporting Information Fig. S8). All these data demonstrated that GQ262 possesses good PK properties.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetics of GQ262 in mice (n = 6).

| Parameter | Route of dosing |

|

|---|---|---|

| iv | po | |

| Dose (mg/kg) | 5 | 15 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.7 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 2471 ± 192 | 1036 ± 267 |

| AUC0‒t (h·ng/mL) | 1625 ± 70 | 2899 ± 358 |

| MRT0‒t (h) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| Vss (L/kg) | 3.9 ± 0.4 | – |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 50.2 ± 2.1 | – |

| F (%) | – | 59.5 |

3. Conclusions

In summary, we developed a novel Gαq/11 inhibitor GQ262 with high efficacy, good security, and augmented PK. GQ262 exhibited outstanding potency in combating UM both in vitro and in vivo, and we also verified the direct interaction between GQ262 and Gαq/11. Discovery of GQ262 provides a new and effective anti-UM drug candidate via directly targeting Gαq/11, however drug-like properties including the Gαq/11 inhibitory potency, metabolic stability, selectivity among normal cells and UM cells, and cardiotoxicity are needed to be further optimized, these works are currently under way in our lab.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

All reagents used in this manuscript are commercially available. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were utilized to characterize chemical structures with a Bruker AVANCE at 400 and 100 MHz. High-resolution mass spectrometer was recorded utilizing Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF. Chemical reactions were monitored by utilizing TLC with 0.2 mm silica gel plates (HSGF254, Huanghai). All compounds are >95% pure by reverse-phase analytical HPLC. See supporting information for HPLC conditions, detailed chemical data, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra.

4.2. Cell culture

The CHO-M1 cells were given to us by Xinmiao Liang (Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) as a generous gift. We cultured the CHO-M1 cells in F12K media (zqxzbio), which was added to penicillin-streptomycin (1% (v/v), Gibco), G418 (0.25 mg/mL, Beyotime), and FBS (10% (v/v), Gibco). MP41 cells, one of UM cell lines, were given to us by Jingxuan Pan (Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University) as a generous gift. 92.1 cells, another UM cell line, were bought from FuHeng BioLogy Co., Ltd. (Shanghai). We cultured MP41 and 92.1 cells in RPMI-1640 (Gibco), which was added to fetal bovine serum (10% (v/v), Gibco). These three cell lines were maintained in 95% air, 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

4.3. IP1 assay

CHO-M1 cells were collected and seeded in 384-well plates. The cell density reached 2 × 104 cells/well. We added test compounds to pre-treat the cells at 37 °C. After incubating for 1 h, carbachol (Sigma) containing LiCl (200 mmol/L) was prepared and added, which achieved the final concentration to 9 μmol/L. After incubating for 1 h, we added the detection solution (2.5% anti-IP1 cryptate Tb conjugate (Cisbio) + IP1 conjugate and lysis buffer (Cisbio) + 2.5% d-myo-IP1-d2 conjugate (Cisbio)) to the plates at room temperature. After incubating for 1 h, the plates were read on an HTRF® compatible reader.

4.4. Cell proliferation inhibition assay

MP41 and 92.1 cells were collected and resuspended in RPMI-1640 (3 × 103 cells/mL). Then we seeded the cells into 96-well plates and placed the plates overnight. After culturing, we added indicated concentrations of compounds to the plates. After incubating for 72 h, we added CCK-8 (10 μL/well). Then, we placed the plates in an incubator for 2–4 h and determined the absorption at 450 nm utilizing a microplate reader. We calculated the IC50 values by utilizing GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. IC50 values were shown as mean ± SEM.

4.5. BRET measurements

HEK293 cells, which expressed AT1 receptor along with Gαq-RLuc8, unlabeled Gβ1, and Gγ2-Venus, were transfected transiently utilizing the standard protocol. In accordance with previously reported procedures45, we collected and seeded the cells into 96-well plates after transfecting for 24 h. The plates were placed in the incubator overnight. Then, 3 and GQ262 were added to pre-treat the cells. After incubating for 1 h, agonist AngII was added, followed by we added coelenterazine (luciferase substrate). Flex Station 3 (Moleculardevices) was utilized to determine the BRET signals.

4.6. Intracellular calcium release measurements

HEK293 cells, which overexpressed AT1R, were utilized to measure calcium release. In accordance with previously reported procedures45, 1 mmol/L Fluo-4 AM, a calcium-sensitive molecular probe, were loaded into the cells at 37 °C. After incubating for 1 h, we added 3 or GQ262 to plates to pre-treat the cells. After treating for 0.5 h, different concentrations of AngII were added. Flex Station 3 (Moleculardevices) was utilized to determine the excitation/emission (485 nm/525 nm).

4.7. Rescue assay

We collected and seeded MP41 cells into six-well plates, and placed the plates in the incubator overnight. Then, we utilized the DharmaFECT (Dharmacon, USA) to transfect siRNA targeting GNA11 (AGAUGAUGUUCUCCAGGUCGAAAGG) or control (AGAAAUGUAGUCUUGACCGCUGAGG) in MP41 cells and GNAQ (GCACAAUUAGUUCGAGAAGUU) or control (UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT) in 92.1 cells. After transfection for 48 h, we placed the cells in 96-well plates. The cell density reached 3000 cells/well. After culturing for 18–24 h, GQ262 was added to pre-treat the cells. After incubating for 72 h, we added CCK-8 (10 μL/well). Then, we placed the plates in the incubator for 2–4 h and determined the absorption at 450 nm utilizing a microplate reader.

4.8. Cellular thermal shift assay

We collected and seeded MP41 cells into six-well plates, and placed the plates in the incubator overnight. Then, GQ262 was added to pre-treat the cells. After incubating for 1 h, we collected the cells and conducted CETSA assay. Then, the cells were divided into 4 parts equally. We heated each sample under different temperature (37, 40, 45, and 50 °C) for 3 min. After cooling at 4 °C, the cells were left to snap frozen at liquid nitrogen for 3 min, then unfrozen at 55 °C, and the process repeated one more time. Subsequently, we centrifuged cell lysates at 4 °C (20,000×g). After centrifuging for 15 min, levels of Gαq/11 were measured by western blot.

4.9. Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

We collected and seeded MP41 cells into six-well plates and placed the plates in the incubator overnight. The cell density reached 3 × 105 cells/well. Then, 3 and GQ262 were added to pre-treat the cells for 48 h. For cell cycle, we washed and fixed the cells at 4 °C by utilizing 70% ethanol. After fixing for 12 h, we stained the cells at 37 °C by utilizing RNase (100 μg/mL) and PI (50 μg/mL) for 0.5 h. For apoptosis, we washed and collected the cells, which were then stained by utilizing 5 μL Annexin V-FITC. After staining for 15 min, we then stained the cells by utilizing 10 μL PI for 5 min. Flow cytometer was utilized to assess the samples (Beckman Coulter, USA).

4.10. Clonogenic assay

We collected and seeded MP41 cells into 12-well plates and placed the plates in the incubator overnight. The cell density reached 4000 cells/well. Next, 3 and GQ262 were added to treat the cells. RPMI-1640 and test compounds were replaced every three days. After incubating for 9 days, we fixed the cells utilizing 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixing for 15 min, crystal violet (Solarbio, China) was utilized to stain the clonogentic cells for 0.5 h. We counted the colony formation by utilizing a Colony-Counter.

4.11. Migration and invasion assay

We collected and seeded MP41 cells into 24-well Transwell upper chambers (1 × 104 cells/well). The lower chamber was added RPMI-1640 containing 20% FBS. The plates were placed overnight in an incubator. Then, 3 and GQ262 were added to pre-treat the cells. After incubating for 48 h, we discarded the cells which situated in the upper chamber, then we stained the cells which situated in the lower chamber utilizing crystal violet (Solarbio, China). After staining for 0.5 h, migrative and invasive cells were observed and counted utilizing a microscope (magnification × 40 and × 100, Nikon).

4.12. Human liver microsome stability assay

We prepared potassium phosphate buffer (100 mmol/L, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mg/mL liver microsome and 5 mmol/L MgCl2 and added to 96-well plates. Next, GQ262 was incubated with the human liver microsome buffer at the concentration of 1 μmol/L. After incubating for 5 min (37 °C), we added 1 mmol/L NADPH to the wells. 150 μL acetonitrile, which included internal standard, was added to quench the reactions at 0, 5, 15, 30, and 45 min. We shook the plates for 10 min (600 rpm). After shaking, the collected samples were centrifuged for 15 min (6000 rpm) and analyzed utilizing LC‒MS/MS.

4.13. Western blot

We lysed the cells or tumor tissues utilizing RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) containing phosphatase inhibitors (Bimake, USA) and protease inhibitors (Beyotime, China). In accordance with previously reported procedures45, we centrifuged the lysates at 4 °C and 15,000 rpm. After centrifuging for 15 min, we separated the supernatants and assessed the protein concentration utilizing a BCA assay. 8%–12% SDS-PAGE gels were utilized to separate the targeted proteins. Next, we transferred target proteins to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA), which were then blocked by utilizing 5% BSA. After 60 min, we incubated the primary antibodies with the membranes overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies contain GAPDH (CST 5174), cleaved caspase-7 (CST 9491), Bcl-2 (CST 3498), Mcl-1 (CST 4572), total YAP (CST 14074), phospho-YAPSer127 (CST 13008), total ERK1/2 (CST 4695), and phospho-ERK1/2Thr202/Tyr204 (CST 4370). After incubating with secondary antibodies, we measured the targeted proteins utilizing an enhanced chemiluminescence.

4.14. MP41 xenograft model

Nude BALB/cnu/nu mice (18–22 g, 6–8 weeks) were brought from Gempharmatech Co, Ltd. (Nanjing, SCXK(Guangdong)2021-0029). The Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University approved the animal procedures (Approval No. SYSU-IACUC-2021-000858). In accordance with previously reported procedures45, the mice with MP41 xenograft tumors were grouped randomly (n = 6/group) and administrated for 21 consecutive days with vehicle, 3 (15 mg/kg/day), or GQ262 (5, 15, or 30 mg/kg/day). The route of administration was intraperitoneal injection (ip), and we monitored the body weight and tumor size every 2 days. On Day 22, we gained the tumor blocks. GraphPad Prism 8.0 software was utilized to analyze the data.

4.15. Pharmacokinetic studies

ICR mice were treated with GQ262 to study the pharmacokinetics. The dose of iv was 5 mg/kg, or the dose of po was 15 mg/kg. After administration, we collected 30 μL blood samples at 0, 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h. Then we centrifuged the samples at 6800×g, 2–8 °C. After centrifuging for 6 min, the samples were kept at −80 °C and measured by LC‒MS/MS. We calculated the pharmacokinetic parameters utilizing WinNonlin, version 7.0 (Pharsight, USA) and showed the data as mean ± SEM.

4.16. Statistical analysis

Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and repeated at least twice except for animal experiments. Data were shown as mean ± SEM. Significance between controls and treatments was assessed by Student's test utilizing GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Animal experiments were analyzed utilizing the one-way ANOVA. The significant differences were considered at the level of ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22077144 and 81973359), Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (No. 2018B030306017, China), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Chiral Molecule and Drug Discovery (2019B030301005, China), Key Reasearch and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B1111110003, China), Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2017BT01Y093, China), National Engineering and Technology Research Center for New Drug Druggability Evaluation (Seed Program of Guangdong Province, 2017B090903004) and Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Project (20200404105YY).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.016.

Contributor Information

Xiaolei Zhang, Email: zhangxlei5@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Xiao-Feng Xiong, Email: xiongxf7@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Xiao-Feng Xiong and Xiaolei Zhang conceived the project. Xiao-Feng Xiong and Yang Ge designed the synthesis, Yang Ge and Jun-Jie Deng performed the synthesis. Yang Ge, Jianzheng Zhu, Lu Liu, Shumin Ouyang, and Zhendong Song performed biological evaluation. Yang Ge, Xiao-Feng Xiong, and Xiaolei Zhang wrote the manuscript, with input from all the authors. All authors have approved the final article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting data to this article:

References

- 1.Gilman A.G. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malbon C.C. G proteins in development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:689–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downes G.B., Gautam N. The G protein subunit gene families. Genomics. 1999;62:544–552. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldham W.M., Hamm H.E. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:60–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell A.P., Smrcka A.V. Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signalling by blocking G proteins. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:789–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon M.I., Strathmann M.P., Gautam N. Diversity of G proteins in signal transduction. Science. 1991;252:802–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1902986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunahara R.K., Dessauer C.W., Gilman A.G. Complexity and diversity of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:461–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katada T., Bokoch G.M., Northup J.K., Ui M., Gilman A.G. The inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory component of adenylate cyclase. Properties and function of the purified protein. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3568–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smrcka A.V., Hepler J.R., Brown K.O., Sternweis P.C. Regulation of polyphosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C activity by purified Gq. Science. 1991;251:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1846707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C.H., Park D., Wu D., Rhee S.G., Simon M.I. Members of the Gq alpha subunit gene family activate phospholipase C beta isozymes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16044–16047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor S.J., Chae H.Z., Rhee S.G., Exton J.H. Activation of the β1 isozyme of phospholipase C by α subunits of the Gq class of G proteins. Nature. 1991;350:516–518. doi: 10.1038/350516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozasa T., Jiang X., Hart M.J., Sternweis P.M., Singer W.D., Gilman A.G., et al. p115 RhoGEF, a GTPase activating protein for Gα12 and Gα13. Science. 1998;280:2109–2111. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart M.J., Jiang X., Kozasa T., Roscoe W., Singer W.D., Gilman A.G., et al. Direct stimulation of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Gα13. Science. 1998;280:2112–2114. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strathmann M.P., Simon M.I. Gα12 and Gα13 subunits define a fourth class of G protein α subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5582–5586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Ge Y., Huang J.X., Strømgaard K., Zhang X., Xiong X.F. Heterotrimeric G proteins as therapeutic targets in drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2020;63:5013–5030. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris A.J., Malbon C.C. Physiological regulation of G protein-linked signaling. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1373–1430. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein L.S., Chen M., Xie T., Liu J. Genetic diseases associated with heterotrimeric G proteins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis C.A., Masters S.B., Spada A., Pace A.M., Bourne H.R., Vallar L. GTPase inhibiting mutations activate the α chain of Gs and stimulate adenylyl cyclase in human pituitary tumours. Nature. 1989;340:692–696. doi: 10.1038/340692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein L.S., Chen M., Liu J. Gsα mutations and imprinting defects in human disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:173–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Raamsdonk C.D., Griewank K.G., Crosby M.B., Garrido M.C., Vemula S., Wiesner T., et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kan Z., Jaiswal B.S., Stinson J., Janakiraman V., Bhatt D., Stern H.M., et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature. 2010;466:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein L.S., Shenker A., Gejman P.V., Merino M.J., Friedman E., Spiegel A.M. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1688–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smrcka A.V. Molecular targeting of Gα and Gβγ subunits: a potential approach for cancer therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jager M.J., Shields C.L., Cebulla C.M., Abdel-Rahman M.H., Grossniklaus H.E., Stern M.H., et al. Uveal melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:24. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smit K.N., Jager M.J., de Klein A., Kili E. Uveal melanoma: towards a molecular understanding. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;75:100800. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.100800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rantala E.S., Hernberg M.M., Piperno-Neumann S., Grossniklaus H.E., Kivela T.T. Metastatic uveal melanoma: the final frontier. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101041. Available from: http://doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Hayre M., Vázquez-Prado J., Kufareva I., Stawiski E.W., Handel T.M., Seshagiri S., et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:412–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Raamsdonk C.D., Bezrookove V., Green G., Bauer J., Gaugler L., O'Brien J.M., et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009;457:599–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoushtari A.N., Carvajal R.D. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations in uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:525–534. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urtatiz O., Van Raamsdonk C.D. Gnaq and Gna11 in the endothelin signaling pathway and melanoma. Front Genet. 2016;7:59. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vader M.J.C., Madigan M.C., Versluis M., Suleiman H.M., Gezgin G., Gruis N.A., et al. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations and downstream YAP activation in choroidal nevi. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:884–887. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim C.Y., Kim D.W., Kim K., Curry J., Torres-Cabala C., Patel S. GNAQ mutation in a patient with metastatic mucosal melanoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:516. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parish A.J., Nguyen V., Goodman A.M., Murugesan K., Frampton G.M., Kurzrock R. GNAS, GNAQ, and GNA11 alterations in patients with diverse cancers. Cancer. 2018;124:4080–4089. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maziarz M., Leyme A., Marivin A., Luebbers A., Patel P.P., Chen Z., et al. Atypical activation of the G protein Gα by the oncogenic mutation Q209P. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:19586–19599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annala S., Feng X., Shrhar N., Eryilmaz F., Patt J., Yang J., et al. Direct targeting of Gαq and Gα11 oncoproteins in cancer cells. Sci Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau5948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larribère L., Utikal J. Update on GNA alterations in cancer: implications for uveal melanoma treatment. Cancers. 2020;12:1524. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnold J.J., Blinder K.J., Bressler N.M., Bressler S.B., Burdan A., Haynes L., et al. Acute severe visual acuity decrease after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin: case reports from randomized clinical trials-TAP and VIP report no. 3. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:683–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh A.D., Turell M.E., Topham A.K. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1881–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croce M., Ferrini S., Pfeffer U., Gangemi R. Targeted therapy of uveal melanoma: recent failures and new perspectives. Cancers. 2019;11:846. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X., Yin M., Dong J., Mao G., Min W., Kuang Z., et al. Tubeimoside-1 induces TFEB-dependent lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 and promotes antitumor immunity by targeting mTOR. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:3134–3149. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vivet-Noguer R., Tarin M., Roman-Roman S., Alsafadi S. Emerging therapeutic opportunities based on current knowledge of uveal melanoma biology. Cancers. 2019;11:1019. doi: 10.3390/cancers11071019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong X.F., Zhang H., Underwood C.R., Harpsøe K., Gardella T.J., Wöldike M.F., et al. Total synthesis and structureactivity relationship studies of a series of selective G protein inhibitors. Nat Chem. 2016;8:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujioka M., Koda S., Morimoto Y., Biemann K.S. Structure of FR900359, a cyclic depsipeptide from Ardisia crenata sims. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2820–2825. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayoub M.A., Damian M., Gespach C., Ferrandis E., Lavergne O., De Wever O., et al. Inhibition of heterotrimeric G protein signaling by a small molecule acting on Gα subunit. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29136–29145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ge Y., Shi S., Deng J.J., Chen X.P., Song Z., Liu L., et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of small molecule Gαq/11 protein inhibitors for the treatment of uveal melanoma. J Med Chem. 2021;64:3131–3152. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishimura A., Kitano K., Takasaki J., Taniguchi M., Mizuno N., Tago K., et al. Structural basis for the specific inhibition of heterotrimeric Gq protein by a small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13666–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003553107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schrage R., Schmitz A.L., Gaffal E., Annala S., Kehraus S., Wenzel D., et al. The experimental power of FR900359 to study Gq-regulated biological processes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10156. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitz A.L., Schrage R., Gaffal E., Charpentier T.H., Wiest J., Hiltensperger G., et al. A cell-permeable inhibitor to trap Gαq proteins in the empty pocket conformation. Chem Biol. 2014;21:890–902. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.