Abstract

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) represent a growing share of the health care workforce, but much of the care they provide cannot be observed in claims data because of indirect (or “incident to”) billing, a practice in which visits provided by an NP or PA are billed by a supervising physician. If NPs and PAs bill directly for a visit, Medicare and many private payers pay 85 percent of what is paid to a physician for the same service. Some policy makers have proposed eliminating indirect billing, but the possible impact of such a change is unknown. Using a novel approach that relies on prescriptions to identify indirectly billed visits, we estimate that the number of all NP or PA visits in fee-for-service Medicare data billed indirectly was 10.9 million in 2010 and 30.6 million in 2018. Indirect billing was more common in states with laws restricting NPs’ scope of practice. Eliminating indirect billing would have saved Medicare roughly $194 million in 2018, with the greatest decrease in revenue seen among smaller primary care practices, which are more likely to use this form of billing.

There are growing numbers of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) in the United States.1 From 2010 to 2021 the number of NPs increased from 91,000 to 325,000,2,3 whereas the number of PAs increased from approximately 75,000 to 149,000.4,5 Prior research has found that the quality and cost of care provided by NPs and PAs is often comparable to that provided by physicians.6–9 These findings, coupled with concerns about physician shortages, have led some policy makers to advocate for greater use of NPs or PAs in the future.2

However, how much and what types of care NP and PAs provide to Americans is unknown because of the practice of indirect (or “incident to”) billing. Indirect billing was originally implemented to offset the costs for physicians of supervising NPs and PAs caring for Medicare beneficiaries.10 If an NP or PA directly bills for a visit, then Medicare and many private payers11 pay 85 percent of what they pay a physician for the same service.10 Under indirect billing, an NP or PA independently evaluates and treats the patient, but the bill is submitted under the supervising physician.10 The payment for such a visit is 100 percent of what is paid to a physician for the same service.10 Under Medicare policy, there are some limitations on the use of indirect billing: it is to be used only after the initial physician relationship has been established, and a physician must be on the premises and available to assist the NP or PA. This supervising physician is not required to be the physician who performed the initial visit and can be trained in any specialty.11

The use of indirect billing has made it difficult to characterize the extent of NP and PA care in the US health care system. Within administrative claims data, a claim for a visit indirectly billed by a supervising physician but provided by an NP or PA is indistinguishable from a claim for an independent visit with the supervising physician.10 The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has called for the elimination of indirect billing because it prevents policy makers from assessing the care delivered by NPs and PAs and increases the costs of the Medicare program.10 However, the impacts of this policy recommendation are hard to assess because it is unclear how frequently indirect billing is used and which practices will be most affected by such a change.

There has been limited prior work quantifying rates of indirect billing. In a 2012 survey, 29 percent of primary care NPs reported that all of their care was indirectly billed, whereas 24 percent indicated that some of their care was indirectly billed.12 Another study using electronic health records data reported that in 2017, 51 percent of primary care visits rendered by an NP were billed indirectly.13 MedPAC has estimated that in 2016, approximately 43 percent of NP office visits and 31 percent of PA office visits were likely billed indirectly.14 None of these studies examined changes over time in indirect billing—and they largely focused on primary care visits—thus, we cannot estimate the future cost of indirect billing to Medicare.

To fill these gaps in knowledge we used a novel approach to identify indirect billing. We exploited the fact that during an indirectly billed NP or PA visit in which a prescription is written, the NP or PA writes a prescription (which is observable in the data as distinct from the visit) even though the physician bills for the visit itself. Thus, we identified NP- and PA-provided care by associating NP and PA prescriptions with their indirectly billed office visits, enabling us to estimate the frequency and cost of indirect billing. We also examined which practices predominantly use indirect billing and therefore would lose revenue if the practice was eliminated. We focus on the Medicare fee-for-service population, given that Medicare is the largest payer for health care in the US and that any policy change in Medicare would likely spill over to the privately insured population.

We describe variation in indirect billing by state NP scope-of-practice laws. Although indirect billing is a national policy, scope of practice is regulated by states and determines an NP’s ability to practice and prescribe medications with or without physician collaboration or supervision. Unlike PA state scope-of-practice laws, which are generally consistent across states,15 there is both considerable variation in NP scope-of-practice laws across states and considerable debate about expanding them. In a state with restricted scope-of-practice laws, a supervising physician might have to be on site regardless of indirect billing rules. We hypothesize that states with restricted NP scope-of-practice laws would have higher rates of indirect billing, as those NPs would be less able to deliver care without the supervision of a physician compared with NPs working in states with full scope-of-practice laws.

Study Data And Methods

Overview

Our Medicare Part D and carrier visits-based approach relied on the key inference that prescriptions can signal who directly cared for the patient. Not all visits result in a prescription, so therefore our analysis was limited to visits that result in a prescription. When an NP or PA writes a prescription, the prescription is recorded under the NP or PA’s national provider identifier (NPI), but if the claim for the outpatient visit in connection with which the prescription was written was recorded under the physician’s NPI, we assumed that the visit was indirectly billed. Conversely, during a visit billed directly by an NP or PA that involved a prescription, both the prescription and claim for the outpatient visit were under the NP or PA’s NPI. Exploiting this inference using claims data enabled us to measure population-level indirect billing in the Medicare program, and thereby the nature of care provided by all NPs and PAs.

The focus of this analysis is on visits, indirectly or directly billed, that were independently provided by the NP or PA. We assumed that visits in which the physician and NP or PA both physically saw the patient resulted in both the prescription and visit under the physician’s NPI. Further, although our method focused on NP and PA visits that resulted in a prescription, we extrapolated these estimates so that we could estimate both the total number of NP and PA visits with indirect billing (those with and those without a prescription) and the spending on these visits. The details and limitations of this approach are outlined below.

Data Sources

Our analysis used a 20 percent random sample of Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2010 to 2018, limited to beneficiaries with Part D coverage in the month of their visit. These data included prescription drug events and outpatient visits. Only office visits (as opposed to visits in the hospital outpatient setting) for established patients (as opposed to new patients) are eligible for indirect billing in Medicare.12 Thus, we began our estimates on prescriptions with an associated established office visit (defined as visits with place of service code 11 and current procedural terminology codes 99211–15).

Methodology To Identify Indirect Billing

We first identified all prescriptions written by NPs and PAs (referred to as “index prescriptions”) (online appendix exhibit 1).16 We linked National Plan and Provider Enumeration System data to identify NPs and PAs via NPIs and taxonomy codes. Second, we identified all established patient office visits (indirect billing can be used only after the initial physician relationship has been established)11 billed by an NP or PA or a physician one day before, on, or one day after the index prescription fill date. Although patients can take many days to fill a prescription after a visit,17 we selected a one-day window as it provides more confidence that the index prescription was prescribed during the associated visit. We allowed for visits one day after the prescription was filled, given that providers might submit bills the day after the visit and not change the date of service. If the NP or PA NPI on the index prescription and visit were the same, we categorized the visit as billed directly. However, if the NPI on the index prescription and visit were different and the visit was billed by a physician, it was considered potentially indirectly billed.

From this group of potentially indirect billed visits, we excluded visits for which we also observed a prescription in this window from the physician NPI because it raised uncertainty about who wrote the prescription associated with the visit, or where there was more than one visit from physicians in different practices (practices were identified used their tax identifiers) during the window in question because it was unclear which of these visits was the associated visit (both exclusions led to <0.70 percent of prescriptions excluded; appendix exhibit 1).16 The remaining visits were considered indirectly billed.

Outcomes

Our main outcome was the fraction of NP and PA visits billed indirectly. The denominator was the number of visits in our sample provided by NPs and PAs (indirectly and directly billed). The numerator was the number of these visits billed indirectly.

We also estimated total visits and spending in 2018 for indirectly billed NP and PA visits across all visits (those with an associated prescription and those without). The details of this extrapolation are in appendix exhibit 2.16 In brief, we take the ratio of indirect-to-direct billed visits that we observe among visits with a prescription and apply that ratio to visits without a prescription (see Appendix for details).16 Given that we used a 20 percent random sample of Medicare beneficiaries, we also multiplied our visit counts and total spending by five to obtain an estimate for the total Medicare fee-for-service population.

Understanding Geographic Variation In Indirect Billing

We also sought to understand what might drive variation across counties in use of indirect billing for NP visits, and specifically the role of scope-of-practice laws. As noted above, unlike PA state scope-of-practice laws, where forty-seven states require supervision by a physician,15 there is considerable variation in NP scope-of-practice laws across states. We hypothesized that rates of indirect billing would be higher in settings in which NPs practiced with less independence. Other factors included were rurality (given that in rural communities, nonphysician providers represent a larger share of the clinical workforce)18 and number of NPs per capita. We fit a county-level linear regression model with the outcome of rate of indirect billing among NPs in 2018. Using data from the Area Health Resource Files19 and American Association of Nurse Practitioners,20 predictors included county-level rurality (defined below), county’s NPs per capita, and state-level NP scope of practice. Standard errors were adjusted for state-level clustering (that is, counties within the same state). In line with CMS guidelines for suppressing small cell values, we only included counties with ten or more NP visits in 2018 (excluded counties accounted for 752 of 2,119,657 NP visits).

We used 2018 data from the American Association of Nurse Practitioners,20 which categorized states as having full, reduced, or restricted NP scope-of-practice laws. States with full scope of practice permit NPs to evaluate patients, order and interpret diagnostic tests, and initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications and controlled substances, under the exclusive licensure authority of the state board of nursing. States with reduced scope of practice either require a career-long regulated collaborative agreement with another health provider for the NP to provide patient care or limit the ability of NPs to engage in at least one element of NP practice. States with restricted practice require career-long supervision, delegation, or team management by another health provider for the NP to provide patient care and limit the ability of NPs to engage in at least one element of NP practice.

Characterizing Practices That Predominantly Use Indirect Or Direct Billing

To better understand which types of practices would be negatively affected by the elimination of indirect billing, we categorized practices with at least one physician and one NP or PA in 2018 as indirect billing practices, direct billing practices, and practices with both direct and indirect billing. Practices were identified by the tax identifier on the visit claim. Indirect billing practices were those for which more than 80 percent of NP and PA visits were billed indirectly. Direct billing practices were defined as practices with more than 80 percent of NP and PA visits billed directly. We selected the 80 percent cutoffs because they were natural cutoffs in the distribution across practices in indirect billing rates. All other practices were defined as practices for which NP and PA visits were billed both directly and indirectly.

For each practice we identified all providers who billed an office visit or wrote a prescription in 2018. We used the specialty codes, provider identifiers, and patient characteristics on these visits to characterize practice type (defined as primary care, specialty, or multispecialty), number of physicians, number of NPs and PAs, and percentage of rural patients (methods detailed in appendix exhibit 3).16 Primary care practices were defined as practices with only primary care physicians (that is, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, general practice, and preventive medicine physicians). Specialty practices were defined as practices with only specialty physicians. Practices with at least one primary care physician and one specialty physician were defined as multispecialty practices. We define rural versus metropolitan patients using the Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Code definition.21

We used a series of chi-square and t-tests to test for bivariate differences between the characteristics of direct and indirect billing practices.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, to address the concern that we were categorizing practices on a limited number of prescriptions, we conducted a sensitivity analysis limiting our sample to practices with at least four “index prescriptions” in a given year (appendix exhibit 4).16

Second, given that patients can take several days to fill a prescription after a visit,17 we examined whether our overall findings were affected by expanding the one-day window requirement. Using 2018 data, we compared our results using a one-day window to results using a window for which visits occurred from five days before through one day after the prescription (appendix exhibit 5).16

Third, because our method focuses on visits with an associated prescription, we examined whether our findings could be driven by a change in the share of visits resulting in a prescription over time. From 2010 to 2018 we measured the proportion of total established office visits with any clinician (NP, PA, physician) that resulted in a prescription, using a one-day window among fee-for-service beneficiaries with Part D coverage from 2010 to 2018 (appendix exhibit 6).16 We also compared established office visits with a prescription with those without a prescription (appendix exhibit 8).16

Limitations

Our work had several limitations. Most important, our method focuses on visits that result in a prescription and we extrapolate those patterns to visits that do not result in a prescription. It is reassuring that the rates of prescriptions associated with established office visits have been stable over time (appendix exhibit 6)16 and that the demographics of visits with and without a prescription are similar (appendix exhibit 8).16 However, there are some differences. For example, visits that result in a prescription are more likely to be for patients who are younger, dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, and disabled. Our estimate of indirect billing rates therefore may be biased to the degree that use of indirect billing differs for visits that result in a prescription versus those that do not result in a prescription. For example, if annual physical exams are unlikely to result in a prescription and they are more likely to be billed indirectly, then our estimate would be too low. We do not know the direction or magnitude of such a bias.

Second, it is impossible to directly link a prescription to a given visit. We assume that a prescription that is filled within a one-day window around a visit is associated with that visit. However, invariably there will be some misclassification of prescriptions. In a sensitivity analysis using a broader time window around a visit, we found that the rates of indirect billing were similar (appendix exhibit 5).16

Third, although the use of tax identification numbers (TINs) to identify practices is common,22 we acknowledge that it is an imperfect proxy to identify practices. Finally, these findings may not be generalizable to other populations, such as those with Medicaid or commercial insurance.

Despite these critical limitations, we believe that this methodology is a valuable contribution to the literature, given the lack of an alternative method of capturing the prevalence of indirect billing on a national basis.

Study Results

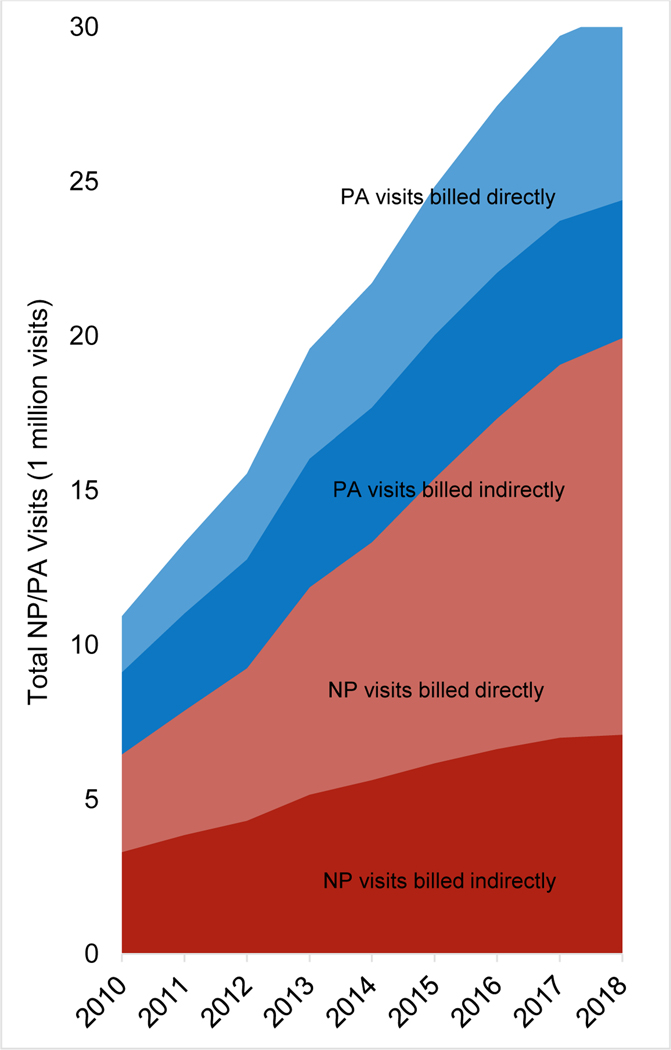

The number of NP and PA visits (both with and without a prescription) billed indirectly increased from 10.9 million in 2010 to 30.6 million in 2018 (exhibit 1). The number of NP visits, both billed directly and billed indirectly, increased from 6.5 million in 2010 to 19.9 million in 2018. The number of PA visits billed both directly and indirectly increased from 4.5 million to 10.6 million.

Exhibit 1. Nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) visits that are directly billed versus indirectly billed, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries for 2010–18.

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 20 percent random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with Part D coverage for 2010–18. NOTES See online appendix exhibit 2 for and annual visits and spending calculation (see note 16 in text). See appendix exhibit 9 for fraction of NP and PA visits and spending for established office visits that are directly billed versus indirectly billed (see note 16 in text).

The fraction of total NP and PA visits billed indirectly decreased from 54.3 percent in 2010 to 37.8 percent in 2018. The fraction of NP visits billed indirectly decreased from 50.9 percent in 2010 to 35.6 percent in 2018. Similarly, among PAs, visits billed indirectly decreased from 59.2 percent in 2010 to 42.0 percent in 2018 (appendix exhibit 9).16

The total spending for NP and PA visits billed indirectly (both with and without a prescription) increased from $513 million in 2010 to $1,291 million in 2018 (a 152 percent change from 2010 to 2018) versus an increase from $282 million to $1,278 million for visits billed directly (a 353 percent change) (appendix exhibit 9).16 Among NPs, spending for visits that was billed indirectly increased from $295 million in 2010 to $811 million in 2018 (a 175 percent change); this spending increased from $218 million to $480 million among PAs (a 120 percent change).

We estimate that Medicare would have saved at least $194 million in 2018 if all NP and PA visits indirectly billed to Medicare were billed directly (detailed in appendix exhibit 2).16

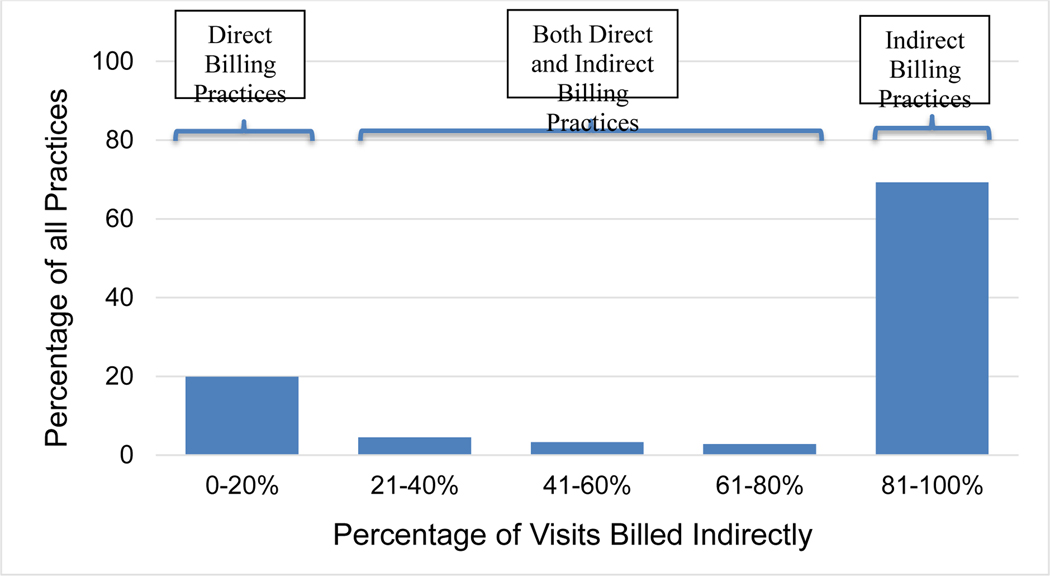

Comparison Of Indirect Versus Direct Billing Practices

The use of indirect billing across practices had a bimodal distribution in 2018. Across all practices, 39,094 (69 percent) were indirect billing practices (defined as having more than 80 percent of their NP and PA visits billed indirectly), 11,210 (20 percent) of practices were direct billing practices (those having more than 80 percent of their total NP and PA visits billed directly), and 6,107 (11 percent) of practices were both direct and indirect billing practices (those billing between 21 percent and 80 percent of their NP and PA visits indirectly) (exhibit 2). The indirect billing practices and the direct billing practices accounted for 23.0 percent and 50.1 percent of all observed NP and PA visits in 2018 (indirect or direct), respectively (data not shown).

Exhibit 2. Variation across practices in fraction of nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) visits billed indirectly, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 2018.

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from 20 percent random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with Part D coverage for 2010–18. NOTES Practice is defined by the taxpayer identification number. The denominator is the total number of visits provided by NPs and PAs in each practice. The numerator is the total number of visits billed indirectly by NPs and PAs in each practice.

Compared with direct billing practices, indirect billing practices had, on average, fewer physicians (2.6 versus 12.3; p < 0.001), had fewer NPs and PAs (4.0 versus 12.2; p < 0.001), were more likely to be primary care practices (50.7 percent versus 43.3 percent; p < 0.001), and were less likely to serve rural patients (21.0 percent versus 33.7 percent; p < 0.001) (exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3:

Characteristics of direct versus indirect billing practices, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 2018

| Direct billing practices | Direct and indirect billing practices | Indirect billing practices | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of practices | 7,270 | 6,107 | 39,094 |

| Practice type (no.) | |||

| Primary care | 3,145 | 2,232 | 19,806 |

| Specialty | 2,507 | 2,204 | 17,487 |

| Multispecialty | 1,618 | 1,671 | 1,801 |

| Number of doctors (mean) | 12.3 | 19.4 | 2.6 |

| Number of NPs and PAs (mean) | 12.2 | 18.8 | 4.0 |

| Percentage of rural patients (mean) | 33.7 | 28.3 | 21.0 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from 20 percent random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with Part D coverage for 2010–18. NOTES Only practices with at least one physician and one NP or PA in 2018 were included. We categorized practices with at least one physician and one NP or PA in 2018 as indirect, direct and indirect, or indirect billing practices. Indirect billing practices were defined as practices with more than 80 percent NP and PA visits billed as “incident to.” Direct billing practices were defined as practices with more than 80 percent of NP and PA visits billed directly. The remaining practices were categorized as direct and indirect billing practices. Unadjusted comparisons for practice type, number of doctors, number of NPs and PAs, and percentage of rural patients are significant (p < 0.001).

In 2018 indirect billing practices were reimbursed, on average, an additional $2,936 per practice by using indirect billing compared with a scenario in which they billed those same visits directly (data not shown).

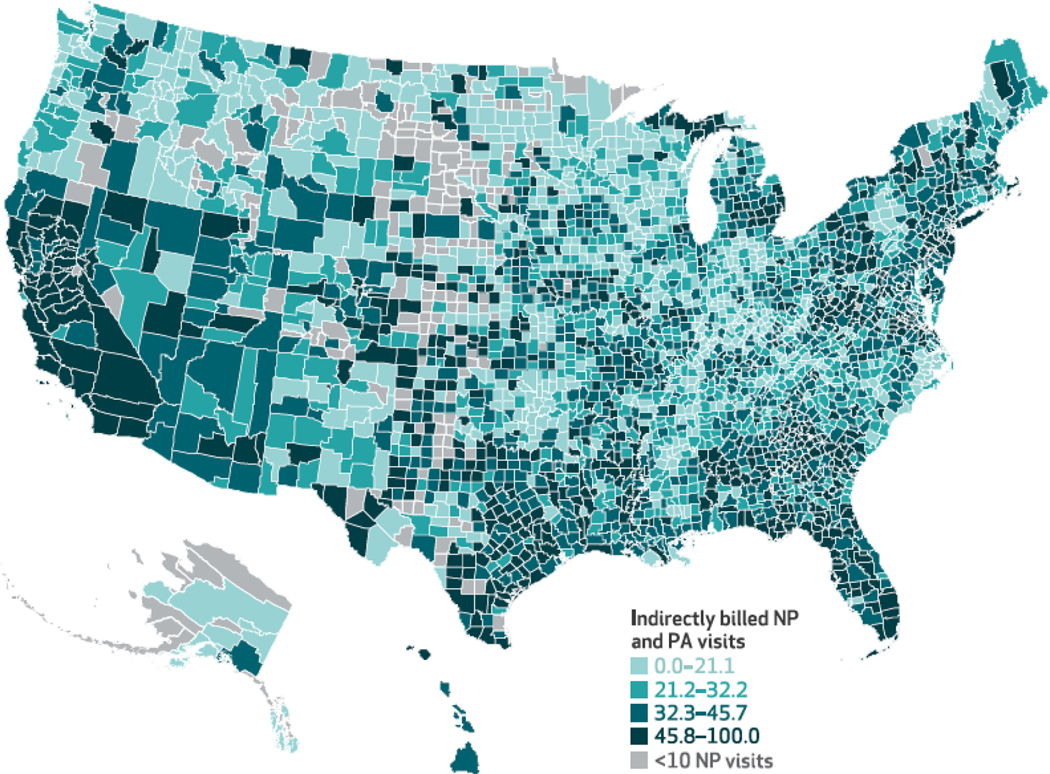

Geographic Variation In Indirect Billing

Across the 2,945 counties in our sample in 2018 that had ten or more NP visits, there is wide geographic variation in the fraction of total NP visits billed indirectly. For example, indirect billing is more common in California, Texas, Florida Georgia, and Alabama (exhibit 4). The median percentage of NP visits billed indirectly was 32.2 percent (interquartile range: 21.2 percent-45.7 percent) (data not shown).

Exhibit 4. Fraction of nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) visits billed indirectly by county, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in 2018.

Source/Note: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 20 percent random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with Part D coverage for 2010–18. NOTE Only counties with 10 or more NP visits in 2018 were included.

Compared with counties located in a restricted NP scope-of-practice-law state, there was less indirect billing in counties with reduced (−7.3 percent; 95% confidence interval, −13.4, −1.2; p = 0.02) and full (−11.1 percent; 95% CI, −17.0, −5.3; p < 0.001) NP scope-of-practice laws (appendix exhibit 7).16

Compared with metropolitan counties (those with a population of one million or more people), there was less indirect billing in other metro counties (those with a population of between 250,000 and one million people) (−5.1 percent; 95% CI, −8.1, −2.0; p < 0.001) and nonmetropolitan, nonrural counties (those with a population of 2,500–20,000 people; −6.0 percent; 95% CI, −9.1, −2.8; p = 0.002) (appendix exhibit 7).16

Results Of Sensitivity Analysis

Limiting our analysis to practices with at least four index prescriptions in a given year or expanding the time window from one to five days did not have a substantive impact on our findings (appendix exhibits 4 and 5).16 The proportion of all established office visits that resulted in a prescription was stable over time (appendix exhibit 6).16

Discussion

Indirect billing is a practice that, to date, has been hard to capture in the US health care system. We introduced a new method for observing indirectly billed services provided by NPs and PAs and found that indirectly billed visits accounted for a large fraction of NP and PA visits and that both the number of indirectly billed visits and spending on those visits is increasing over time. If indirectly billed established office visits involving a prescription had been directly billed, the Medicare program would have saved at least $194 million in 2018 because of NPs and PAs being reimbursed at 85 percent the physician rate, with smaller primary care practices being more negatively affected by the lost revenue than other practices. There is substantial geographic variation in indirect billing, with much greater use of indirect billing in states with restricted scope-of-practice laws for NPs.

Our estimates of the frequency of indirect billing (38 to 54 percent, depending on year) are consistent with prior estimates from surveys (29 percent of primary care NPs in surveys state they bill indirectly) and other claims or electronic health records-based methods (30–40 percent).9–11 We extend this work by examining trends over time and variation in the use of indirect billing.

We find that practices largely fell into two groups: those that indirectly billed NP and PA visits and those that billed NP and PA visits directly. It remains unclear what drives how practices decide to bill for NP and PA visits and merits further research. One possibility is that practices are weighing the increase in revenue versus the costs of the administration requirements for indirect billing.

Policy Implications

Our results highlight that prior research that quantifies the role of NPs and PAs only using direct billing23–25 substantially underestimates the role of NPs and PAs in the US health care system and, conversely, overestimates the role of physicians. Recognizing its limitations, we hope that our methodology will be used by policy makers and researchers to better characterize the role and impact of NPs and PAs in the US health care system. For example, prior research has used Medicare claims to compare the resource utilization and quality of care provided by NPs and PAs versus physicians.26,27 The results of such studies may differ if one accounts for indirectly billed services.

Our findings inform the ongoing debate about eliminating indirect billing. If indirect billing of office visits involving a prescription was eliminated and NPs and PAs continued to be paid 85 percent on the dollar, we estimate that it would save the Medicare program $194 million per year across all established office visits. It could also have other spillover effects. Patient out-of-pocket payments might be lower if the visits themselves are reimbursed less. Eliminating indirect billing may remove the physician oversight requirement in state-level NP scope-of-practice laws (for example, requiring a physician to be on site at all times), possibly resulting in increased practice efficiency. Eliminating indirect billing may also encourage more independent practice among NPs and PAs where it is allowed. However, this decrease in Medicare spending means less revenue for practices, and smaller primary care practices in particular.

Any potential savings assumes that NP and PAs continue to be paid at 85 percent of the physician reimbursement rate. There have been many calls to reimburse NPs and PAs at the same rate as physicians.28 This strategy would obviously not result in savings to the Medicare program, but would likely eliminate the practice of indirect billing, as there would be no financial incentive to use it. Further, it may result in improved practice efficiency, as practices would no longer have to ensure that they were meeting the regulatory requirements of indirect billing.

Our findings also inform the ongoing debate about NP scope-of-practice laws. We find that indirect billing is more common in states with restricted or reduced NP scope-of-practice laws. This implies that the use of indirect billing could be reduced by expanding NP scope of practice. One must also consider potential physician backlash if indirect billing was eliminated but some states maintained restricted NP scope-of-practice laws. Research indicates that relaxing scope-of-practice laws has no effect on NP visit volume or allocation of patients to NPs.29 Thus, physicians might argue that they are facing an unreimbursed mandate in which the physician must maintain oversight requirements for NP and PA visits without any reimbursement for the time required.

Conclusion

There is ongoing debate about whether indirect billing should be eliminated. Using a new methodology, we estimated the frequency of indirect billing and the variation in its use across counties and practices. Eliminating indirect billing would have saved Medicare $194 million in 2018, with a greater decrease in revenue seen among smaller primary care practices, which are more likely to use this form of billing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. K23 AG058806-01) and the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. R01 MH112829, T32MH019733). The authors thank Rebecca Shyu for contributing to data visualization and manuscript preparation efforts. This work does not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or any other organization with which the authors are affiliated.

Biographies

Sadiq Y. Patel, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Haiden A. Huskamp, Harvard University.

Austin B. Frakt, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Harvard University, and Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.

David Auerbach, State of Massachusetts, Boston, Massachusetts.

Hannah T. Neprash, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Michael Lawrence Barnett, Harvard University.

Hannah O. James, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Ateev Mehrotra, Harvard University.

Notes

- 1.Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Colla CH. Accountable care organizations’ increase in nonphysician practitioners may signal shift for health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):1080–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Implications of the rapid growth of the nurse practitioner workforce in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Japsen B. Number of nurse practitioners surpasses 325,000. Forbes [serial on the Internet]. 2021 May 4 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2021/05/04/number-of-nurse-practitioners-eclipses-325000/?sh=4f475bdc6f26

- 4.Hooker RS, Cawley JF, Everett CM. Predictive modeling the physician assistant supply: 2010–2025. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(5):708–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Statistical profile of certified PAs: annual report National Commission on Certification of PAs [Internet]. Johns Creek (GA): NCCPA; 2021. Jan [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.nccpa.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Statistical-Profile-of-Certified-PAs-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Erp RMA, van Doorn AL, van den Brink GT, Peters JWB, Laurant MGH, van Vught AJ. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care plus: a systematic review. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carranza AN, Munoz PJ, Nash AJ. Comparing quality of care in medical specialties between nurse practitioners and physicians. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;33(3):184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtzman ET, Barnow BS. A comparison of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care physicians’ patterns of practice and quality of care in health centers. Med Care. 2017;55(6):615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham CM, Norful AA, Stone PW, Poghosyan L. Cost-effectiveness of advanced practice nurses compared to physician-led care for chronic diseases: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2019;37(6):293–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buerhaus PI, Skinner J, McMichael BJ, Auerbach DI, Perloff J, Staiger DO, Skinner L. The integrity of MACRA may be undermined by “incident to billing” coding. Health Affairs Blog. doi: 10.1377/hblog20180103.135358 [DOI]

- 11.Gosfield AG. The ins and outs of “incident-to” reimbursement. Fam Pract Manag. 2001;8(10):23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donelan K, DesRoches CM, Dittus RS, Buerhaus P. Perspectives of physicians and nurse practitioners on primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neprash HT, Smith LB, Sheridan B, Hempstead K, Kozhimannil KB. Practice patterns of physicians and nurse practitioners in primary care. Med Care. 2020;58(10):934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system [Internet]. Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2018. [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Medical Association, Advocacy Resource Center. Physician assistant scope of practice [Internet]. Chicago (IL): AMA; 2018. Jan 13 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/arc-public/state-law-physician-assistant-scope-practice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 17.Business Wire. Specialty pharmacists report process delays of up to 10 days to get patients started on treatment. Business Wire [serial on the Internet]. 2020. May 13 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200513005049/en/Specialty-Pharmacists-Report-Process-Delays-10-Days

- 18.Naylor KB, Tootoo J, Yakusheva O, Shipman SA, Bynum JPW, Davis MA. Geographic variation in spatial accessibility of U.S. healthcare providers. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resources Health and Administration Services. Area Health Resources Files [Internet]. Rockville (MD): HRSA; [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips SJ. 30th annual APRN legislative update: improving access to healthcare one state at a time. Nurse Pract. 2018;43(1):27–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes [Internet]. Washington (DC): USDA, ERS; 2020. Dec 10 [cited 2022 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivers PA, Glover SH. Health care competition, strategic mission, and patient satisfaction: research model and propositions. J Health Organ Manag. 2008;22(6):627–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooker RS, McCaig LF. Use of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care, 1995–1999. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(4):231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and electronic communication. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray KN, Martsolf GR, Mehrotra A, Barnett ML. Trends in visits to specialist physicians involving nurse practitioners and physician assistants, 2001 to 2013. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1213–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buerhaus P, Perloff J, Clarke S, O’Reilly-Jacob M, Zolotusky G, DesRoches CM. Quality of primary care provided to Medicare beneficiaries by nurse practitioners and physicians. Med Care. 2018;56(6):484–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraze TK, Briggs ADM, Whitcomb EK, Peck KA, Meara E. Role of nurse practitioners in caring for patients with complex health needs. Med Care. 2020;58(10):853–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bischof A, Greenberg SA. Post COVID-19 reimbursement parity for nurse practitioners. Online J Issues Nurs. 2021;26(2):3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith LB. The effect of nurse practitioner scope of practice laws on primary care delivery. Health Econ. 2022;31(1):21–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.