Abstract

The Sumatran orang-utan (Pongo abelii) reference genome was first published in 2011, in conjunction with ten re-sequenced genomes from unrelated wild-caught individuals. Together, these published data have been utilized in almost all great ape genomic studies, plus in much broader comparative genomic research. Here, we report that the original sequencing Consortium inadvertently switched nine of the ten samples and/or resulting re-sequenced genomes, erroneously attributing eight of these to the wrong source individuals. Among them is a genome from the recently identified Tapanuli (P. tapanuliensis) species: thus, this genome was sequenced and published a full six years prior to the species’ description. Sex was wrongly assigned to five known individuals; the numbers in one sample identifier were swapped; and the identifier for another sample most closely resembles that of a sample from another individual entirely. These errors have been reproduced in countless subsequent manuscripts, with noted implications for studies reliant on data from known individuals.

Subject terms: Genetics, Zoology, Evolution

Introduction

Alongside their publication of a Sumatran orang-utan (Pongo abelii) draft genome assembly in 2011, The Orang-utan Genome Consortium re-sequenced the genomes of ten additional unrelated wild-caught individuals – ostensibly five Sumatran and five Bornean (P. pygmaeus) orang-utans – using short-read Illumina sequencing1. Their manuscript, and its accompanying 297 Gb of sequence data, has since been cited more than 500 times. During the course of our own studies, however, we noted several inconsistencies between the data made available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and their accompanying metadata and descriptors in the paper.

We found no record of a sample with the identifier “KB5543”, for example, in the Frozen Zoo repository, the reported source of a sample attributed to the orang-utan, Louis. The closest match in their database to this ID was for another sample, “15543”, which derived from a different individual. We also observed that the identifier “KB9528”, as reported for the orang-utan Baldy in the manuscript’s Tables S4-1, was catalogued as a sample from an “African pig” – though, in a supplemental file, it was correctly denoted as KB9258, which derived from another orang-utan. The sample identifier “SB550”, as reported for the orang-utan Doris, appeared to reference a studbook number (i.e. “SB”) that belonged to another sequenced orang-utan, Sibu. The sex reported for five individuals also contradicted their known sexes, as had been recorded in contemporary studbook records2, plus differed from the sexes assigned to each sample in Locke et al.’s supplementary data.

Thus, we were driven to reconsider the identities of each genome’s source individual, through re-analysis of the published data combined with new molecular studies. Herein, we report that nine of the ten samples and/or published genomes were erroneously labelled in the original Nature publication. We present the corrected data and discuss the implications for other published works.

Methods

We first mapped the re-sequencing reads of all 10 Locke et al. whole genomes, plus those previously published from 27 conspecifics3,4, to the latest iteration of the (female) orang-utan reference genome (ponAbe35). To this, we had concatenated a recent orang-utan Y chromosome assembly6. Using the idxtools function in samtools 1.147, we inferred sex by comparing the ratios to which sequence reads were mapped against the X and Y chromosomes. Following two rounds of bootstrapped base recalibration, we then jointly called genotypes with GATK 4.1.8.08, all as previously described9. We randomly sampled 1,000,000 biallelic autosomal SNPs with no missing genotypes and ≥5% minor allele frequency (MAF), pruned linked loci in PLINK10 (–indep-pairwise 50 10 0.1), and assigned populations in ADMIXTURE 1.3911 as supervised with provenance data reported for the conspecifics3,4 (K = 3).

Additionally, we sampled and assayed eight orang-utans known to be first, second or third-degree relatives of seven of those purportedly sequenced by Locke et al., using the Illumina iScan Multi-Ethnic Global Array, also as previously described12. The reproduction of those seven, and thus these known relationships, had been contemporaneously recorded2 (Fig. 1). To convert the microarray intensity data to variant calls, we mapped the probe flank sequences to ponAbe3 (using --fasta-flank) and exported genotypes (--sam-flank) with the bcftoools7 plugin gtc2vcf (https://github.com/freeseek/gtc2vcf), subject to the following filter parameters: meanR_AB < 0.2, meanR_AA < 0.2, meanR_BB < 0.2, Cluster_Sep < 0.35, meanTHETA_AA > 0.3, meanTHETA_BB < 0.7, meanTHETA_AB < 0.3 and > 0.7, devTHETA_AA > 0.025, devTHETA_AB ≥ 0.07, devTHETA_BB > 0.025 and GenTrain_Score < 0.7. We then re-genotyped all 37 whole genomes at each of the resulting loci, as previously described9; merged these with the microarray genotype VCF, and LD-pruned and MAF-filtered biallelic SNPs precisely as aforementioned. With a view to avoiding the spurious kinship associations that typify highly structured data, we then bootstrapped ADMIXTURE’s cross-validation procedure to infer the most suitable K (trialling 1 through 10) before estimating kinship coefficients (Φij) in REAP13.

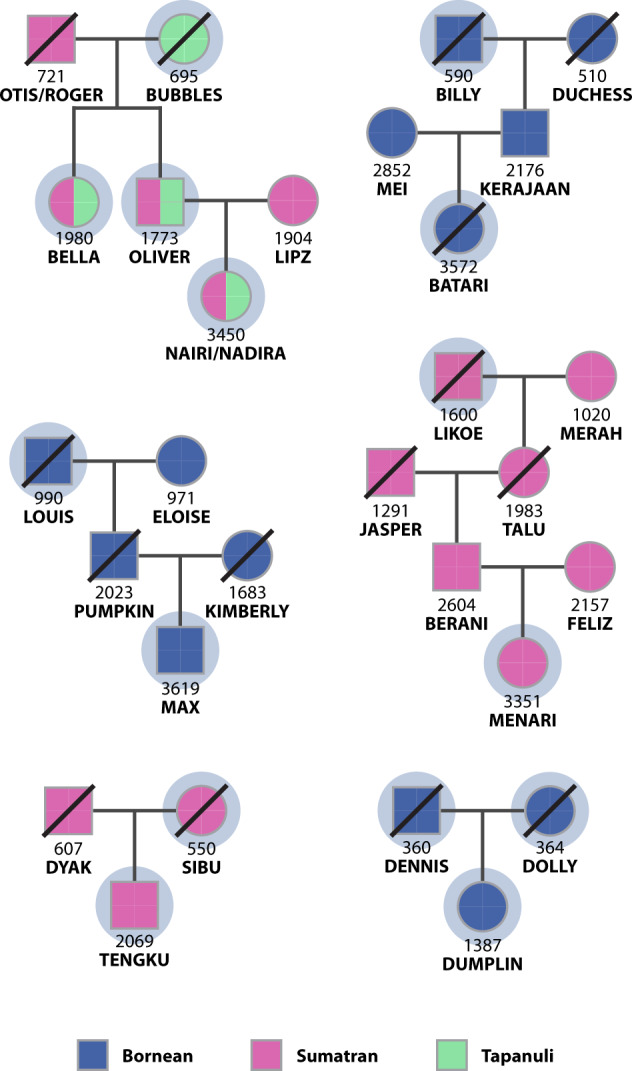

Fig. 1.

Genogram depicting relationships between orang-utans sampled by Locke et al. and known relatives assayed in this study. Orang-utans used in the kinship analysis (Table 1) are circled. The species affiliations of uncircled orang-utans reflect those purported by contemporary studbook records.

We adopted a tri-fold method to confirm each sample’s identity. Identities were first inferred with an exclusionary approach, from computed (versus known and reported) sex and species. Each was then confirmed, where available, when observed kinship coefficients resembled those expected from known relationships. Third, we reviewed the historical biomaterial records retained by the Frozen Zoo, the original source of the samples, plus notes from the Laboratory Information System (LIMS) retained at Washington University in Saint Louis, where the samples were originally sequenced. Identity was assigned to a given sample when all these factors concorded.

Results

We observed X:Y sequence ratios in known males to range from 0.369–0.569 (mean 0.476) and in females from 4.114 to 5.827 (mean 4.973). From this, we interpreted that sex had been incorrectly assigned by Locke et al. to the sample SAMN00007170. This sample was inferred to be female (4.170) and thus cannot have derived from Baldy as purported. The species of each sample was correctly reported, though we inferred that the sample SAMN00007170 derived from a Tapanuli orang-utan (Fig. 2). This species was not formally described until 20174.

Fig. 2.

Ancestry proportions of the Locke et al. orang-utans, as supervised with provenance data from 27 conspecifics sampled across the natural range of the genus3,4. Sample SAMN000007170 derives from a Tapanuli orang-utan.

Kinship analyses linked one or more known relatives to seven of the ten samples sequenced by Locke et al. Specifically, we linked Billy to his granddaughter, Batari (observed/expected kinship coefficients: 0.116/0.125); Dumplin to her parents, Dennis (0.162/0.25) and Dolly (0.19/0.25); Sibu to her son, Tengku (0.246/0.25); Louis to his grandson, Max (0.082/0.125); Likoe to his great granddaughter, Menari (0.063/0.063); and Bubbles to her son, Oliver (0.233/0.25), daughter, Bella (0.242/0.25) and granddaughter, Nairi/Nadira (0.036/0.125). Admixture (K = 3) and kinship were inferred from a total of 1,132,210 biallelic SNPs.

We assigned identity to the remaining three samples as molecular sex, sample and LIMS records were all concordant, and as the relatedness data had excluded other possible candidates. Table 1 corrects the record as originally presented in Nature.

Table 1.

Corrected identities and metadata for the samples sequenced and published by Locke et al.1, as deposited in the NCBI BioSample database.

| BioSample ID | Reported identities and metadata | Corrected/validated identities and metadata | Known relative and inferred kinship | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab ID | ISB | Name | Sp. | Sex | Lab ID | ISB | Name | Sp. | Sex | X:Y | ISB | δ0 | δ1 | δ2 | Exp. Φij | Φij | |

| SAMN00007164 | KB5404 | 590 | Billy | B | F | KB5404 | 356 | Dinah | B | F | 4.556 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SAMN00007165 | KB4204 | 364 | Dolly | B | M | KB4204 | 590 | Billy | B | M | 0.506 | 3572 | 0.655 | 0.226 | 0.119 | 0.125 | 0.116 |

| SAMN00007166 | KB5406 | 356 | Dinah | B | F | KB5406 | 364 | Dolly | B | F | 5.015 | 1387 | 0.432 | 0.376 | 0.192 | 0.250 | 0.190 |

| SAMN00007167 | KB5405 | 360 | Dennis | B | M | KB5405 | 360 | Dennis | B | M | 0.547 | 1387 | 0.411 | 0.530 | 0.060 | 0.250 | 0.162 |

| SAMN00007168 | KB5543 | 990 | Louis | B | M | — | 990 | Louis | B | M | 0.464 | 3619 | 0.823 | 0.025 | 0.152 | 0.125 | 0.082 |

| SAMN00007169 | KB5883 | 550 | Sibu | S | M | KB5883 | 1600 | Likoe | S | M | 0.444 | 3351 | 0.971 | 0.000 | 0.221 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| SAMN00007171 | KB4661 | 695 | Bubbles | S | M | KB4661 | 732 | Baldy | S | M | 0.432 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SAMN00007172 | KB4361 | 1600 | Likoe | S | F | KB4361 | 53 | Doris | S | F | 4.625 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SAMN00007173 | SB550 | 53 | Doris | S | F | — | 550 | Sibu | S | F | 4.264 | 2069 | 0.313 | 0.390 | 0.298 | 0.250 | 0.246 |

| SAMN00007170 | KB9528 | 732 | Baldy | S | M | KB9258 | 695 | Bubbles | T | F | 4.170 | 1980 | 0.200 | 0.632 | 0.168 | 0.250 | 0.242 |

| 1773 | 0.186 | 0.696 | 0.118 | 0.250 | 0.233 | ||||||||||||

| 3450 | 0.771 | 0.229 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.036 | ||||||||||||

Originally reported data are reproduced from Locke et al.’s Tables S4-1. “ISB” denotes International Studbook Number; for species, “B” indicates Bornean (P. pygmaeus), “S” indicates Sumatran (P. abelii), and “T” indicates Tapanuli (P. tapanuliensis). The X:Y ratios noted for sex are those inferred, as detailed, from each mapped BAM file. “Lab ID” is the internal identifier used by the sequencing facility, as variously recorded by Locke et al. Relatedness is reported as the probability that each sequenced orang-utan shares 0, 1 and 2 alleles identical by descent with a known relative (i.e. δ0, δ1, and δ2, respectively), plus the expected/theoretical (Exp.) and computed kinship coefficient (Φij).

Discussion

Because Locke et al. focused solely on genome content, their discrepancies have no bearing on the accuracy of their data or their manuscript’s published findings. These errors have had considerable impact on other studies that utilized the published data, however, particularly those dependent on using data from known individuals. Three of our co-authors (GLB, EDF, AK) write from first-hand experience: reliant on tables and metadata from the original Nature publication, we came perilously close to incorrectly reporting that Baldy, a male orang-utan who lived at the Sacramento Zoo, was the first of the recently described Tapanuli species to be captured and exported from a wild population – a full five decades before his species’ formal description. On the contrary, this dubious honour belongs to Bubbles, a female orang-utan who lived at the San Diego Zoo. Though beyond the scope of our manuscript, the implications of this switch have not escaped our attention: principally, that Bubbles produced eight Sumatran x Tapanuli hybrid descendants, who were previously thought to be Sumatran. The genetic integrity of the captive population is therefore unexpectedly compromised, as we present in detail in a manuscript that is currently under review.

Though we eventually caught these errors, others did not. Mattle-Greminger et al. (2018) reproduced eight erroneous sample identities in their paper, meaning each of the genomes they analysed were from different animals than reported14. Sudmant et al. (2013) reproduced seven such errors, thus also misattributing samples15. Neither Ma et al. (2013) nor Beeravolu et al. (2018) recognized that the sample identities were wrong, though as they reported only sample IDs (versus animal identities), no corrections to their manuscripts are warranted16,17. As sample identities are normally only reported in supplemental data – which is not always indexed by search engines – we cannot easily ascertain the full extent to which papers citing Locke et al. have reproduced these errors.

Given these findings and implications, we have corrected the samples’ identities in the NCBI BioSample database. Tables detailing the revisions made are included in Supplementary File 1. We respectfully ask that those utilizing these updated identities cite this article in Scientific Data, in addition to the Correction concurrently published in Nature.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was performed using the compute resources and assistance of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) in the Department of Computer Sciences. The CHTC is supported by UW-Madison, the Advanced Computing Initiative, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, and the National Science Foundation, and is an active member of the Open Science Grid, which is supported by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. We thank Audubon Zoo, Birmingham Zoo, Cameron Park Zoo, the Center for Great Apes, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Dallas Zoo, El Paso Zoo, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo, Houston Zoo, Indianapolis Zoo, Kansas City Zoo, Little Rock Zoo, Louisville Zoo, Metro Richmond Zoo, Milwaukee County Zoo, Phoenix Zoo, Sedgwick County Zoo, Topeka Zoo, Toronto Zoo and ZooTampa at Lowry Park for providing samples from known descendants, and the Orangutan Species Survival Plan (SSP) for approval by recommendation to the SSP’s member institutions. We are especially grateful to Dr Cynthia Steiner, who provided metadata from the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. This work was funded in part by the Arcus Foundation, the Eppley Foundation for Research, Inc., the Ronna Noel Charitable Trust, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services through National Leadership Grant MG-249168-OMS-21 (all to GLB). AK was supported by the Morris Animal Foundation. Research reported in this publication was also supported in part by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, under award number P51OD011106 to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center and conducted in part at a facility constructed with support from the Research Facilities Improvement Program under grant numbers RR15459-01 and RR020141-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

G.L.B., E.D.F. and A.K. performed the laboratory and computational analyses; R.S.F., L.A.-F. and J.O.N. reviewed archival laboratory records; G.L.B. wrote the manuscript, and all authors edited and contributed to the final version.

Data availability

Locke et al. deposited their sequence reads in the Short Read Archive under the accession codes detailed in their Supplementary Information1. Our microarray data from known relatives have been deposited in Figshare in their original IDAT format18.

Code availability

No custom code was used to generate or process the data described in the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-022-01602-0.

References

- 1.Locke DP, et al. Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes. Nature. 2011;469:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature09687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones, M. L. Studbook of the orang utan, Pongo pygmaeus (Zoological Society of San Diego, 1980).

- 3.Prado-Martinez J, et al. Great ape genetic diversity and population history. Nature. 2013;499:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nater A, et al. Morphometric, behavioral, and genomic evidence for a new orangutan species. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:3487–3498.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronenberg ZN, et al. High-resolution comparative analysis of great ape genomes. Science. 2018;360:eaar6343. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cechova M, et al. Dynamic evolution of great ape Y chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. 2020;117:26273–26280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001749117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danecek P, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Auwera, G. A. & O’Connor, B. D. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra 1st edn (O’Reilly Media, 2020).

- 9.Banes GL, et al. Genomic targets for high-resolution inference of kinship, ancestry and disease susceptibility in orang-utans (Genus: Pongo) BMC Genomics. 2020;21:873. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fountain ED, et al. Cross-species application of Illumina iScan microarrays for cost-effective, high-throughput SNP discovery. Front Ecol Evol. 2021;9:629252. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.629252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton T, et al. Estimating kinship in admixed populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattle-Greminger MP, et al. Genomes reveal marked differences in the adaptive evolution between orangutan species. Genome Biol. 2018;19:193. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudmant PH, et al. Evolution and diversity of copy number variation in the great ape lineage. Genome Res. 2013;23:1373–1382. doi: 10.1101/gr.158543.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma X, et al. Population genomic analysis reveals a rich speciation and demographic history of orang-utans (Pongo pygmaeus and Pongo abelii) PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e77175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeravolu CR, Hickerson MJ, Frantz LAF, Lohse K. ABLE: blockwise site frequency spectra for inferring complex population histories and recombination. Genome Biol. 2018;19:145. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banes GL, Fountain ED, Karklus A. 2022. Nine of ten samples were mistakenly switched by The Orang-utan Genome Consortium. Figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Banes GL, Fountain ED, Karklus A. 2022. Nine of ten samples were mistakenly switched by The Orang-utan Genome Consortium. Figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Locke et al. deposited their sequence reads in the Short Read Archive under the accession codes detailed in their Supplementary Information1. Our microarray data from known relatives have been deposited in Figshare in their original IDAT format18.

No custom code was used to generate or process the data described in the manuscript.