Abstract

Aim: To determine the prevalence of apical periodontitis (AP) and the frequency of root canal treatment in a sample of Spanish adults. Design: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Setting: Barcelona, Spain. Participants: A total of 397 adult subjects, 49% males and 51% females. Methods: Digital panoramic radiographs were used. Periapical status was scored according to the periapical index. Results were analysed statistically using the chi-squared test and logistic regression. Results: Radiographic signs of AP in one or more teeth were found in 135 patients (34%). The prevalence of AP was significantly higher in males (42.3%) than females (26.1%) [odds ratio (OR) = 2.1; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.4–3.2; P = 0.0007]. At least one root-filled tooth (RFT) was found in 233 patients (59%). Twenty-six per cent of subjects with RFT had at least one RFT with AP. The prevalence of AP increased with age (P < 0.05). Patients with RFT showed a higher prevalence of AP (42%) relative to patients without RFT (23%) (OR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.5–3.7; P = 0.00013). Adjusting for age, gender and teeth number, endodontic status remained significantly associated with periapical status (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.4–3.6; P = 0.0005). Conclusions: Both the prevalence of AP and the frequency of root canal treatment are high among Spanish adults. AP affects more frequently RFT relative to untreated teeth. Patients with one or more RFT have a greater likelihood of having AP than patients without RFT.

Key words: Apical periodontitis, endodontic treatment, root canal treatment

INTRODUCTION

Endodontic and periapical status are important parameters that can predict tooth survival and the future need for dental treatment1. Endodontic epidemiology aims to determine the distribution and prevalence of apical periodontitis (AP) and its determinants in different populations evaluated by the presence/absence of AP2.

Several epidemiological studies have reported that 23.8–83.7% of adults have AP3., 4., 5., which raises an important public health problem in many countries concerning the medical, economic and ethical repercussions6., 7.. Furthermore, prevalence rates of AP as high as 52.2%1, 58.1%8, 60.0%9 and 61.0%10 have been reported to be associated with root-filled teeth (RFT). In Spain, the only published epidemiological study to date11 reported a prevalence of AP of 61% and of RFT with AP of 64.5% in an adult sample. These data have been suggested to reflect the realistic outcome of endodontic treatment in the general population12., 13..

The purpose of the present study was to determine the prevalence of AP and the frequency of root canal treatment in a sample of Spanish adults, analysing the association between radiographic periapical status and previous root canal treatment.

METHODS

The sample consisted of 397 subjects, 194 males (48.9%) and 203 females (51.1%), attending for routine dental treatment (not emergency care) at the University of Barcelona, Faculty of Dentistry, between the years 2009 and 2011. The criteria for inclusion in the study were that the patients should be attending for the first time. Patients younger than 18 years were excluded. The Ethics Committee of the Dental Faculty approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent. The research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Radiographic examination

Periapical and endodontic status were diagnosed on the basis of the examination of digital panoramic radiographs. Two trained radiographic technicians obtained the panoramic radiographs using a digital ortho-pantomograph machine (Promax®, Planmeca, class 1, type B, 80 kHz; Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland).

Radiographic evaluation

All teeth, excluding third molars, were recorded. Teeth were categorised as RFT if they had been filled with a radiopaque material in the root canal(s). The following information was recorded on a structured form for each subject: (i) number of teeth present; (ii) number and location of teeth without root fillings having identifiable periapical lesions; (iii) number and location of RFT; and (iv) number and location of RFT having identifiable periapical lesions.

The periapical status was assessed using the periapical index (PAI) score14, as described previously15. Briefly, each of the roots was categorised as: (i) normal periapical structure; (ii) small changes in bone structure; (iii) changes in bone structure with some mineral loss; (iv) periodontitis with well-defined radiolucent area; and (v) severe periodontitis with exacerbating features. Each category used in the PAI represents a step on an ordinal scale of registration of periapical inflammation. PAI > 2 is considered to be a sign of AP. The periapical status of all teeth and the frequency of RFT were determined. The worst score of all roots was taken to represent the PAI score for multirooted teeth.

Observers

Three observers with extensive clinical experience in endodontics examined the radiographs. Before evaluation, the observers participated in a calibration course for the PAI system, which consisted of 100 radiographic images of teeth (gold standard atlas), some root-filled and some not, kindly provided by Dr Ørstavik. Each tooth was assigned to one of the five PAI scores using visual references (also provided by Dr Ørstavik) for the five categories within the scale. After scoring the teeth, the results were compared with the gold standard atlas and Cohen’s kappa was calculated (0.81–0.85).

The inter-observer and intra-observer reproducibility were determined. The intra-observer reproducibility was evaluated by the repeat scoring of 50 patients, 2 months after the first examination. These patients were randomly selected. Before the second evaluation of the radiographs, each observer was recalibrated in the PAI system by scoring of the 100 standard images. The intra-observer agreement test on the PAI scores of the 50 patients produced a Cohen’s kappa in the range 0.86–0.93. Cohen’s kappa for inter-observer variability was in the range 0.82–0.89. The consensus radiographic standard was the simultaneous interpretation by the three examiners of all radiographs for each subject16., 17..

Statistical analysis

Raw data were entered into Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). All analyses were performed in an SPSS environment (Version 12.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-squared test and logistic regression analysis were used to determine the significance of the results. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The average patient age was 52.0 ± 15.7 years. The distribution of patients by age, gender and number of teeth is illustrated in Table 1. The average number of teeth per patient was 23.6 ± 5.8 (median, 25). No significant differences between males and females were found with regard to the number of teeth (P > 0.05). However, the number of teeth decreased significantly with age (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Distribution of patients by age, gender and number of teeth

| Age group (years) |

No. of patients (%) | Male (%)/female (%) | No. of teeth (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 34 (8.8) | 29.4/70.6 | 29.8 ± 1.6 |

| 30–39 | 66 (16.6) | 54.0/46.0 | 26.7 ± 3.7 |

| 40–49 | 75 (18.9) | 49.9/50.1 | 25.6 ± 4.5 |

| 50–59 | 85 (21.4) | 48.2/51.8 | 23.6 ± 5.2 |

| 60–69 | 84 (21.2) | 48.8/51.2 | 21.7 ± 5.0 |

| ≥70 | 53 (13.4) | 56.6/43.4 | 16.8 ± 5.7 |

| Total | 397 (100) | 48.9/51.1 | 23.6 ± 5.8 |

SD, standard deviation.

AP in one or more teeth was found in 135 patients (34.0% prevalence), and 233 patients (58.7% prevalence) had at least one RFT (Table 2). Among subjects with RFT, 60 (25.8%) had AP affecting at least one RFT. The prevalence of AP was significantly higher in males (42.3%) than in females (26.1%) [odds ratio (OR) = 2.1; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.4–3.2; P = 0.0007]. No significant differences between males and females were found for RFT and RFT with AP (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Distribution of patients with apical periodontitis (AP), root-filled teeth (RFT) and root-filled teeth with AP (RFT-AP) by gender

| No. of patients (%) | AP (%) | RFT (%) | RFT-AP (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 194 (48.9) | 82 (42.3) | 120 (61.9) | 35 (29.2) |

| Females | 203 (51.1) | 53 (26.1) | 113 (55.7) | 25 (22.1) |

| Total | 397 (100) | 135 (34.0) | 233 (58.7) | 60 (25.8) |

| OR females | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| OR males | 2.1** | 1.3* | 1.4* |

RFT-AP of all RFTs. OR, odds ratio.

P > 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The total number of teeth examined was 9390, 259 (2.8%) of which had AP (PAI ≥ 3) (Table 3). The number of RFT was 604 (6.4%), 144 (23.8%) of which had AP. Males had more teeth with AP (3.5%) than females (2.1%) (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.3–2.1; P = 0.00009), as well as more RFT (OR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.1–1.5; P = 0.006). There was no correlation between sex and number of RFT with AP (P > 0.05), but gender correlated significantly with the number of untreated teeth with AP (OR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.3–2.7; P = 0.001). The prevalence of AP in RFT was significantly higher (23.8%) than that in untreated teeth (1.3%) (OR = 23.6; 95% CI = 18.2–30.7; P = 0.0000000).

Table 3.

Distribution of teeth with apical periodontitis (AP), root-filled teeth (RFT), root-filled teeth with AP (RFT-AP) and untreated teeth with AP (UT-AP) by gender

| No. of teeth | AP (%) | RFT (%) | RFT-AP (%) | UT-AP (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 4970 | 106 (2.1) | 287 (5.8) | 62 (21.6) | 44 (0.9) |

| Males | 4420 | 153 (3.5) | 317 (7.2) | 82 (25.9) | 71 (1.7) |

| Total | 9390 | 259 (2.8) | 604 (6.4) | 144 (23.8) | 115 (1.3)† |

| OR females | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| OR males | 1.6** | 1.3** | 1.3* | 1.9** |

RFT-AP of all RFTs. OR, odds ratio.

P > 0.05; **P < 0.01.

RFT-AP versus UT-AP: P < 0.01.

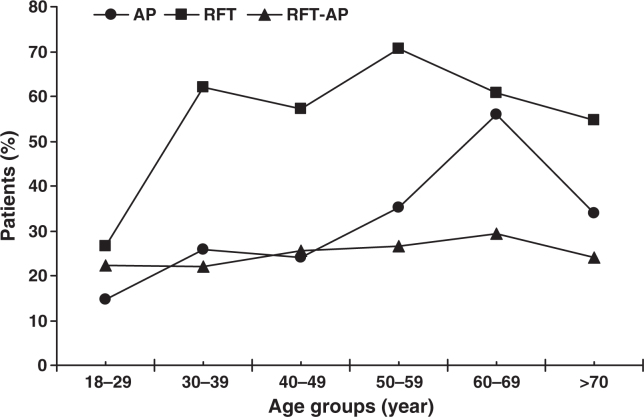

The distribution of patients by age according to their periapical and endodontic status was analysed (Figure 1). The overall prevalence of AP increased with age, reaching a maximum at 60–69 years (56.0%). After 30 years, the prevalence of endodontic treatment exceeded 50% and the percentage of RFT with AP was practically constant (22–29%) in all age groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients with apical periodontitis (AP), root-filled teeth (RFT) and root-filled teeth with AP (RFT-AP) by age.

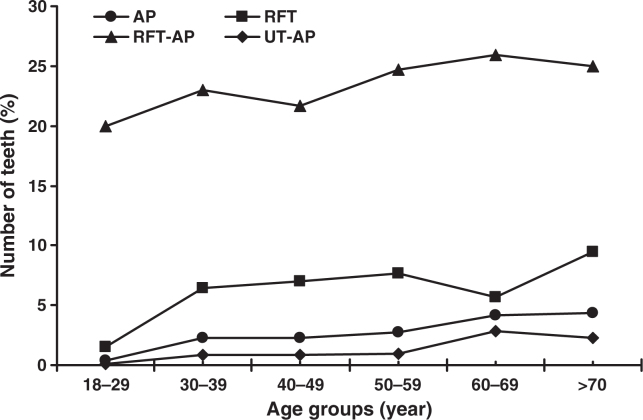

The percentage of teeth with AP increased slowly throughout life, peaking in the group older than 70 years (4.4%) (Figure 2). The proportion of RFT increased with age, reaching a maximum in the group aged 70 years or above (9.4%).The highest percentages of RFT with AP (26%) and untreated teeth with AP (2.9%) were found in the 60–69-year age group.

Figure 2.

Distribution of teeth with apical periodontitis (AP), root-filled teeth (RFT), root-filled teeth with AP (RFT-AP) and untreated teeth with AP (UT-AP) by age.

The correlation between periapical and endodontic status was analysed (Table 4). Patients with one or more RFT showed a higher prevalence of AP (41.6%) relative to patients without RFT (23.2%) (OR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.5–3.7; P = 0.00013). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was run with age, gender (0, female; 1, male), teeth number and endodontic status (0, no RFT; 1, one or more RFT) as explanatory variables and periapical status dichotomised (0, AP absent; 1, AP present) as the dependent variable (Table 5). Adjusting for age, gender and teeth number, the endodontic status remained significantly associated with periapical status (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.4–3.6; P = 0.0005).

Table 4.

Correlation between periapical and endodontic status

| Periapical status | AP present | AP absent | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endodontic status | |||

| Patients with RFT | 97 | 136 | 233 |

| Patients without RFT | 38 | 126 | 164 |

| Total | 135 | 262 | 397 |

AP present, patients with one or more teeth with apical periodontitis (AP). AP absent, patients with no tooth with AP. Patients with RFT, patients with one or more root-filled teeth (RFT). Patients without RFT, patients with no RFT.

χ2 test = 13.804; P = 0.00013.

Odds ratio (OR) for patients with RFT = 2.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.5–3.7).

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the influence of the explanatory variables age, gender, teeth number and endodontic status (0, patients without root-filled teeth; 1, patients with one or more root-filled teeth) on the dependent variable ‘periapical status’ [0, apical periodontitis (AP) absent; 1, patients with one or more teeth with AP]

| Explanatory variable | B | P | Odds ratio | 95% CI, inferior limit | 95% CI, superior limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.0318 | 0.0007 | 1.0323 | 1.0135 | 1.0515 |

| Gender | 0.6769 | 0.0028 | 1.9678 | 1.2615 | 3.0694 |

| No. of teeth | 0.0136 | 0.5753 | 1.0137 | 0.9666 | 1.0631 |

| Endodontic status | 0.8187 | 0.0005 | 2.2675 | 1.4264 | 3.6046 |

CI, confidence interval.

Overall model fit: χ2 = 41.1064; df = 4; P = 0.0000.

DISCUSSION

The study population consisted of patients treated at the Barcelona University Faculty of Dentistry, and does not represent a random sample of the adult Catalonian population. The extrapolation of the results to the general population must be performed with caution. However, the recruitment of subjects was the same as that used by others8., 10., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24., the cohort reflected the characteristics of a general population and there was no skewed recruitment from a socio-economic perspective. Moreover, general dental care at the dental school in Barcelona does not attract lower fees when compared with dental care in private practice. Thus, the results of this study may provide useful data to assess trends concerning the prevalence of AP and endodontic treatment in Barcelona, Catalonia and Spain.

The sample size of the present study (397 patients) is high compared with that of other studies on endodontic epidemiology3., 12., 18., 20., 21., 25., 26., and with the study by Jiménez-Pinzón et al.11 (180 patients). The sample incorporated similar proportions of males (49%) and females (51%). In other epidemiological studies, the samples consisted of more women than men4., 9., 21., 27., including the earlier study of Jiménez-Pinzón et al.11 on periapical and endodontic status in Spain, whose sample included 64% women and 37% men. This may constitute a recruitment bias or reflect certain sociological aspects of the studied population.

The age distribution of the sample was balanced. In contrast, other studies on the epidemiology of AP have analysed population samples in which younger individuals (18–39 years) have made up the majority of the sample4., 5., 7., 9., 10., 13., 18., 20., 28..

In the present study, panoramic radiography and PAI14 were used to score periapical status. Other previous investigations on periapical status have used panoramic radiographs3., 4., 5., 10., 18., 20., 22., 23., 25., 29., 30., 31., 32.. Panoramic images indicate a more severe degree of bone loss than do periapical images when used to image periodontal bone disease, although there is a high concordance between the findings of the two types of radiograph33. However, it has been suggested that periapical radiographs are more accurate than panoramic radiographs in the assessment of periapical pathology34. An underestimation of periapical lesions has been reported when panoramic radiography is used to assess the periapical status30, but the difference from periapical radiography is not statistically significant35., 36.. The fact that all teeth can be seen on one panoramic radiograph, the relatively low exposure to ionising radiation, the convenience of panoramic radiographs and the speed with which they can be obtained are advantageous when compared with full-mouth periapical radiographs4. Nevertheless, cone beam computed tomography, an extra-oral imaging system which produces three-dimensional scans of the maxillofacial skeleton, is useful in overcoming the limitations of conventional radiography for the detection of AP37. A recent study38 has suggested that cone beam computed tomography is 100% successful in identifying periapical lesions, compared with a 25% success rate for intra-oral radiographs, concluding that routine radiography (panoramic or periapical) seriously underestimates the prevalence of AP by a factor of four.

The PAI score has been widely used in the literature to assess the periapical status1., 3., 7., 21., 24., 25., 27., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., and therefore the results of this study can be more appropriately compared with these reports. The intra-observer (Cohen’s kappa = 0.86–0.93) and inter-observer (Cohen’s kappa = 0.82–0.89) reproducibility were acceptable. As noted previously7., 21., PAI is mainly used with a cut-off at two, according to the work of Ørstavik et al.14. The choice of the cut-off at two for PAI is debatable and a cut-off at unity for the evaluation of periapical health might be more appropriate7.

The mean number of teeth per person in this study was 23.6, in agreement with a previous report on the prevalence of AP in a sample of the Spanish population (24.7)13, and with other cross-sectional studies performed on adult European populations4., 8., 9., 10., 25., 26., 30..

The results of the present study showed that 34% of patients have at least one tooth with AP (PAI ≥ 3). This prevalence of AP is in agreement with that found in other investigations that have used panoramic radiographs to assess the periapical status, such as studies carried out in Portugal (26%)25, Ireland (33%)46 and the Netherlands (45%)18. However, in these three studies, as well as in the present one, the possibility of an underestimation of periapical lesions exists30. Moreover, workers who have used periapical radiographs to assess the periapical status have found a higher prevalence of AP, such as studies carried out in Lithuania (70%)3, Spain (61%)13, Greece (86%)9 and Japan (70%)27. Such findings from related studies should be compared with caution because of the variations in sampling procedure, age and gender of the participants, type of radiograph examined and criteria for the diagnosis of periapical disease.

The number of teeth with AP (PAI ≥ 3) was 259, representing 2.8% of the total. Other studies have found similar results, ranging from 1.5% to 4.2%1., 10., 13., 23., 25., 39.. However, this value is lower than the percentages reported by De Moor et al.20 (6.6%), Boucher et al.21 (7.4%), Lupi-Pegurier et al.22 (7.3%), Allard & Palmqvist47 (9.8%) and Georgopoulou et al.9 (13.6%). The range is large, probably as a result of the variation among populations examined and the radiological technique used to assess the periapical status.

The results of this study showed that AP was more likely to be detected in males (42%) than in females (26%) (OR = 2.1; P < 0.01), but there was no significant difference by gender in the number of RFT with AP. Other studies have not found differences by gender with regard to the prevalence of AP9., 13., 21., although Genc et al.48 found a higher prevalence of RFT with AP in males, suggesting that it could reflect the greater interest of women in receiving dental care and in attending for check-ups. Segura-Egea et al.42 found an increased prevalence of AP in smokers compared with nonsmokers. Thus, the higher prevalence of AP in males could be explained by the higher frequency of smoking in males relative to females in the Catalonian population.

Of the 397 subjects having a total of 9390 natural teeth, 233 (59%) had at least one RFT, a lower percentage than communicated by Imfeld49 in Switzerland (78%) and Sidaravicius et al.3 in Lithuania (84%), but similar to that reported in a Greek population (66%)9. The higher percentage of patients with RFT in the present study compared with the previous finding of Jiménez-Pinzón et al.11 in Spain (41%) can be explained by the fact that the sample population analysed in Andalusia was younger (mean age, 37 ± 16 years) than that in the present investigation (mean age, 52 ± 16 years). Nevertheless, a lowest level of dental health care could also explain the smaller percentage (2.0%) of patients having RFT in the Andalusian population11, three times lower than that found in the present study (6.4%). However, other studies have also found a lower prevalence of RFT, in the range 1.3–4.8%1., 4., 7., 10., 18., 23., 25., 39..

However, the total percentage of RFT found in the present study (6.4%) was low compared with the results of other studies3., 21., 22., 28., 49., 50., 51., which were in the range 8.6–26.0%. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that, first, the survey population was not representative of the whole country. Second, the differences in healthcare services in the various countries could account for these discrepancies. Lastly, the variations in age stratification of the patient samples in the various studies are likely to contribute to these differences. Older patients usually have more RFT2., 30., as reported in the present study.

The present study showed that 604 teeth had undergone root canal treatment and that a periapical lesion was found in 144 of these (23.8%). This result is comparable with the values reported in previous studies carried out in Norway30 (18–25.6%), Turkey4 (18.2%), Portugal25 (21.7%), the Netherlands26 (24.1%), Sweden28 (24.5%), Ireland46 (25%), Sweden47 (27%) and France21., 22. (29.7–31.5%). However, this percentage is low compared with the results of Sidaravicius et al.3 in Lithuania (35%), Tsuneishi et al.27 in Japan (40%), Kabak & Abbott52 in Belarus (45%), Dugas et al.23 in Canada (45.4%), Kirkevang et al.1 in Denmark (52.2%), Sunay et al.31 in Turkey (53.5%), Touréet al.7 in Senegal (56.1%), Saunders et al.8 in the UK (58.1%), Georgopoulou et al.9 in Greece (60%), Weiger et al.10 in Germany (61%) and Al-Omari et al.5 in Jordan (87%). This high prevalence of AP associated with RFT is of concern, as the prognosis for teeth presenting with periapical disease is poor7. In follow-up studies, it has been demonstrated that up to 50% of teeth exhibiting AP will be extracted36., 53..

Interestingly, the percentage of RFT with AP found in the present study (23.8%) was lower than that found in another study carried out in Spain (64.5%)13. In Turkey, two investigations performed in different regions of the country also reported dissimilar percentages of RFT with AP4., 31.. However, it should be noted that periapical pathosis is not always detected radiographically. Furthermore, from the periapical lesions seen on a radiograph, it is not possible to determine whether or not they are healing4. Some of the radiolucencies associated with RFT, and identified as AP in this study, may have represented healing lesions, particularly if the time elapsed since treatment was <2 years23. However, the negative predictive value of radiographs with regard to AP is 0.6754, and therefore the prevalence of AP reported in the present study could also be an underestimation of the real situation. Thus, because of the cross-sectional design of this survey, some of the observed periapical radiolucencies may represent persistent AP, whereas others may be incompletely healed lesions after root canal treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Both the prevalence of AP and the frequency of root canal treatment are high among Spanish adults. AP affects more frequently RFT relative to untreated teeth. Patients with one or more RFT have a greater likelihood of AP than patients without RFT.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirkevang LL, Hörsted-Bindslev P, Ørstavik D, et al. Frequency and distribution of endodontically treated teeth and apical periodontitis in an urban Danish population. Int Endod J. 2001;34:198–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksen HM, Kirkevang L-L, Petersson K. Endodontic epidemiology and treatment outcome: general considerations. Endod Topics. 2002;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidaravicius B, Aleksejuniene J, Eriksen HM. Endodontic treatment and prevalence of apical periodontitis in an adult population of Vilnius, Lithuania. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1999;15:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1999.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulsahi K, Gulsahi A, Ungor M, et al. Frequency of root-filled teeth and prevalence of apical periodontitis in an adult Turkish population. Int Endod J. 2008;41:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Omari MA, Hazaa A, Haddad F. Frequency and distribution of root filled teeth and apical periodontitis in a Jordanian subpopulation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;111:e59–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figdor D. Apical periodontitis: a very prevalent problem. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:651–652. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.130322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Touré B, Kane AW, Sarr M, et al. Prevalence and technical quality of root fillings in Dakar, Senegal. Int Endod J. 2008;41:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders WP, Saunders EM, Sadiq J, et al. Technical standard of root canal treatment in an adult Scottish subpopulation. Br Dent J. 1997;182:382–386. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgopoulou M, Spanaki-Voreadi AP, Pantazis N, et al. Frequency and distribution of root filled teeth and apical periodontitis in a Greek population. Int Endod J. 2005;38:105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiger R, Hitzler S, Hermle G, et al. Periapical status, quality of root canal fillings and estimated endodontic treatment needs in an urban German population. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1997.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Pinzón A, Segura-Egea JJ, Poyato M, et al. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and frequency of root-filled teeth in an adult Spanish population. Int Endod J. 2004;37:167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.0143-2885.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman S. In: Essential Endodontology. Ørstavik D, Pitt Ford T, editors. Blackwell Munksgaard Ltd; Oxford, UK: 2008. Expected outcomes in the prevention and treatment of apical periodontitis; pp. 408–469. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tavares PBL, Bonte E, Boukpessi T, et al. Prevalence of apical periodontitis in root canal-treated teeth from an urban French population: influence of the quality of root canal fillings and coronal restorations. J Endod. 2009;35:810–813. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ørstavik D, Kerekes K, Eriksen HM. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:20–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1986.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segura-Egea JJ, Jiménez-Pinzón A, Ríos-Santos JV, et al. High prevalence of apical periodontitis amongst type 2 diabetic patients. Int Endod J. 2005;38:564–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flint DJ, Paunovich E, Moore WS, et al. A diagnostic comparison of panoramic and intraoral radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushton VE, Horner K, Worthington HV. Screening panoramic radiography of new adult patients: diagnostic yield when combined with bitewing radiography and identification of selection criteria. Br Dent J. 2002;9:275–279. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Cleen MJ, Schuurs AH, Wesselink PR, et al. Periapical status and prevalence of endodontic treatment in an adult Dutch population. Int Endod J. 1993;26:112–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1993.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley M, Spangberg LSW. The prevalence and technical quality of endodontic treatment in an American subpopulation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Moor RJ, Hommez GM, De Boever JG, et al. Periapical health related to the quality of root canal treatment in a Belgian population. Int Endod J. 2000;33:113–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boucher Y, Matossian L, Rilliard F, et al. Radiographic evaluation of the prevalence and technical quality of root canal treatment in a French subpopulation. Int Endod J. 2002;35:229–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lupi-Pegurier L, Bertrand M-F, Muller-Bolla M, et al. Periapical status, prevalence and quality of endodontic treatment in an adult French population. Int Endod J. 2002;35:690–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dugas NN, Lawrence HP, Teplitsky PE, et al. Periapical health and treatment quality assessment of root-filled teeth in two Canadian populations. Int Endod J. 2003;36:181–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segura-Egea JJ, Jiménez-Pinzón A, Poyato-Ferrera M, et al. Periapical status and quality of root fillings and coronal restorations in an adult Spanish population. Int Endod J. 2004;37:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marques MD, Moreira B, Eriksen HM. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and results of endodontic treatment in an adult, Portuguese population. Int Endod J. 1998;31:161–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1998.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters LB, Lindeboom JA, Elst ME, et al. Prevalence of apical periodontitis relative to endodontic treatment in an adult Dutch population: a repeated cross-sectional study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Yamanaka R, et al. Radiographic evaluation of periapical status and prevalence of endodontic treatment in an adult Japanese population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ödesjö B, Hellden L, Salonen L, et al. Prevalence of previous endodontic treatment, technical standard and occurrence of periapical lesions in a randomly selected adult, general population. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1990.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksen HM, Bjertness E, Ørstavik D. Prevalence and quality of endodontic treatment in an urban adult population in Norway. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1998;4:122–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1988.tb00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eriksen HM, Bjertness E. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and results of endodontic treatment in middle-aged adults in Norway. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1991;7:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1991.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunay H, Tanalp J, Dikbas I, et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of the periapical status and quality of root canal treatment in a selected population of urban Turkish adults. Int Endod J. 2007;40:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ríos-Santos JV, Ridao-Sacie C, Bullón P, et al. Assessment of periapical status: a comparative study using film-based periapical radiographs and digital panoramic images. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e952–e956. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akesson L, Rohlin M, Håkansson J, et al. Comparison between panoramic and posterior bitewing radiography in the diagnosis of periodontal bone loss. J Dent. 1989;17:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(89)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohlin M, Kullendorff B, Ahlqwist M, et al. Observer performance in the assessment of periapical pathology: a comparison of panoramic with periapical radiography. DentoMaxilloFac Radiol. 1991;20:127–131. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20.3.1807995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhammed AH, Manson-Hing LR, Ala B. A comparison of panoramic and intraoral radiographic surveys in evaluating a dental clinic population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:108–117. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahlqwist M, Halling A, Hollender L. Rotational panoramic radiography in epidemiological studies of dental health. Comparison between panoramic radiographs and intraoral full mouth surveys. Swed Dent J. 1986;10:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estrela C, Bueno MR, Leles CR, et al. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and panoramic and periapical radiography for detection of apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2008;34:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel S, Dawood A, Mannocci F, et al. Detection of periapical bone defects in human jaws using cone beam computed tomography and intraoral radiography. Int Endod J. 2009;42:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksen HM, Berset GP, Hansen BF, et al. Changes in endodontic status 1973–93 among 35-year-olds in Oslo, Norway. Int Endod J. 1995;28:129–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1995.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkevang LL, Wenzel A. Risk indicators for apical periodontitis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:59–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frisk F, Hugoson A, Hakeberg M. Technical quality of root fillings and periapical status in root filled teeth in Jönköping, Sweden. Int Endod J. 2008;41:958–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segura-Egea JJ, Jiménez Pinzón A, Rios Santos JV, et al. High prevalence of apical periodontitis amongst smokers in a sample of Spanish adults. Int Endod J. 2008;41:310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segura-Egea JJ, Jimenez-Moreno E, Calvo-Monroy C, et al. Hypertension and dental periapical condition. J Endod. 2010;36:1800–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segura-Egea JJ, Castellanos-Cosano L, Velasco-Ortega E, et al. Relationship between smoking and endodontic variables in hypertensive patients. J Endod. 2011;37:764–767. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López-López J, Jané-Salas E, Estrugo-Devesa A, et al. Periapical and endodontic status of diabetic patients in Catalonia, Spain: cross-sectional study. J Endod. 2011;37:598–601. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loftus JJ, Keating AP, McCartan BE. Periapical status and quality of endodontic treatment in an adult Irish population. Int Endod J. 2005;38:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allard U, Palmqvist S. A radiographic survey of periapical conditions in elderly people in a Swedish country population. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1986.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Genc Y, Gulsahi K, Gulsahi A, et al. Assessment of possible risk indicators for apical periodontitis in root-filled teeth in an adult Turkish population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e72–e77. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imfeld TN. Prevalence and quality of endodontic treatment in an elderly urban population of Switzerland. J Endod. 1991;17:604–607. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)81833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersson K, Lewin B, Hakansson J, et al. Endodontic status and suggested treatment in a population requiring substantial dental care. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1989;5:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1989.tb00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soikkonen KT. Endodontically treated teeth and periapical findings in the elderly. Int Endod J. 1995;28:200–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1995.tb00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kabak Y, Abbott PV. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and the quality of endodontic treatment in an adult Belarusian population. Int Endod J. 2005;38:238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirkevang LL, Vaeth M, Horsted-Bindslev P, et al. Longitudinal study of periapical and endodontic status in a Danish population. Int Endod J. 2006;39:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barthel CR, Zimmer S, Trope M. Relationship of radiologic and histologic signs of inflammation in human root-filled teeth. J Endod. 2004;30:75–79. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]