Abstract

Introduction:

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranked first among cancers reported in males and ranked third amongst females in Saudi Arabia. CRC cancer symptoms or symptoms secondary to treatment, such as diarrhea, constipation, fatigue and loss of appetite are very common and has significant negative effects on the quality of life (QoL).

Methods:

This project was a cross-sectional study of colorectal cancer survivors diagnosed between 1 January 2015 and May 2017. Assessment was performed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), the colorectal cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-CR 29) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Data on potential predictors of scores were also collected.

Results:

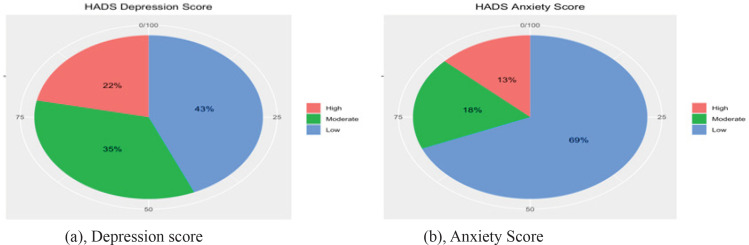

115 CRC patients from Middle, Eastern and Western regions of the KSA participated in the study. Participants have unexpectedly low global health score with a mean of 56.9±31.3. Physical functioning scale had the lowest score of 61.3±27.7. Regarding the generic symptoms of cancer, fatigue was the worst symptom, followed by appetite loss. Psychological wellbeing assessment utilizing HADS reveals alarming outcomes for survivors of CRC in the KSA with high proportion of participants with moderate to severe depression (55%) and a good proportion of participants with moderate to high anxiety (31%). Only 3.7% of participants reported receiving psychosocial support.

Discussion:

Results of this project reveal an overall trend of low scores of quality of life amongst colorectal cancer patients in the KSA when compared with regional or international figures. Consistent results for psychological wellbeing were reached. We recommend routine screening for quality of life and psychological wellbeing and including the outcomes per individual patient care. Psychological support is highly needed for cancer survivors.

Key Words: Colorectal cancer, quality of life, psychological wellbeing, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem in the KSA. It is the second leading cause of death in the KSA. Colorectal ranked first among cancers reported in males and ranked third amongst females. The five-year overall survival for 1994–2004 was 44.6% for patients with colorectal cancer (Al-Ahwal et al., 2013). In 2018, 4007 new colorectal cancer cases were diagnosed in the KSA, contributing to 14.4% of all cancers (Who, 2018).

The overall Age-standardized Incidence Rate (ASR) was 13.9 per 100,000. ASR for males was 16.1 per 100,000, and for females was 10.9 per 100,000 (Who, 2018). The highest ASR was in the Riyadh region at 15.7 per 100,000 (Who, 2018).

Colorectal cancer (CRC) in this paper refers to cases of colon cancer, rectal cancer, or colorectal cancer. CRC cancer symptoms or symptoms secondary to treatment, such as diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, and loss of appetite are very common and has significant negative effects on the quality of life (QoL) (Steginga et al., 2009; Gray et al., 2011; Pan and Tsai, 2012). Consequently, CRC patients have significantly poorer physical and mental quality of life scores when compared with the general population or with patients without cancer (Smith et al., 2008). Stage of cancer, site of the colorectal cancer, pathological coding, age of the patient, cancer recurrence, type of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy regimen, and stoma use are the key determinants of the quality of life and psychological wellbeing of colorectal cancer patients (Schmidt et al., 2005; Paika et al., 2010; Cardin et al., 2012). Studies have shown that QoL score are worse in rectal as compared to colon cancer survivors. This association could be justified by differences in symptoms, treatment modalities particularly need for stoma, and therapy duration (El Alami et al., 2021).

A study showed that diarrhea, fecal control and constipation were the most important symptoms that affect quality of life scores of colorectal cancer patients, while other studies showed that fatigue and loss of appetite were the most important predictors (Caravati-Jouvenceaux et al., 2011; Tsunoda et al., 2007).

Treatment modalities of colorectal cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Adverse events due to chemotherapy such as nausea, vomiting, and neutropenia leads to deteriorations in quality of life (QoL) (Kim, 2009). Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy is another common adverse effect associated with poorer QoL. Therefore, with proper management of chemotherapy associated toxicities, such as dosage reduction or supportive treatment for adverse effects can improve the quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors (Mols et al., 2013).

Impotence, dyspareunia, dysuria and fecal incontinence were other reported complications from radiation therapy. Some patients develop hemorrhagic cystitis secondary to radiotherapy (Andriole et al., 1987; Chong et al., 2005)

Patients who were current stoma users had worst scores than non-users or ex-users in sore skin, embarrassment, while the ex-users had worst fecal incontinence means score, when compared with the remaining participants. Stoma early complications prevalence varies from 13.1% to 69.4% (Kann, 2008), while the prevalence rates of overall late complications vary from a low of 6% to highs exceeding 76% in selected series (Husain and Cataldo, 2008). There are several approaches to reduce such high complications rates (Husain and Cataldo, 2008; Kann, 2008). Therefore, preventive measures should be applied and patients’ counseling should focus on control of feeling of embarrassment.

The impact of colorectal cancer diagnosis, complications or the disease or management has been associated with negative psychological impact. In a study from the US, investigators used the Brief Symptom Inventory as a screening tool for anxiety and depression. Results of this study showed a prevalence rates of 35% for distress, 24% anxiety and 19% depression (Zabora et al., 2001). Results from Jordan using Hospital Anxiety and Depression scaled revealed that a large proportion of colorectal cancer survivors have high rate of moderate to severe anxiety and depression with a large proportion of undiagnosed and uncounseled patients (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014) .

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Saudi Arabia assessed quality of life in a cohort of colorectal cancer patients at one center in Riyadh using European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaires—Core30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) showed a good global score. The lowest scores were reported for the emotional scales (Almutairi et al., 2016). Another study was in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia showed the results. This study also showed that pain, fatigue, and insomnia were the most stressful symptoms (Younis, 2019).

The main limitations of published studies from the KSA on the quality of life of colorectal cancer patients is that they were conducted at one site, and quality of life was limited to caner general domain without including Colorectal cancer domain and a more specific questionnaires for the psychological wellbeing. Therefore, it was proposed to conduct a cross-sectional study on a representative sample of colorectal cancer patients at 12 to 36 months after initial diagnosis. This would allow assessing intermediate and long-term consequences of colorectal cancer like pain, coping with a stoma, sexual problems, and psychosocial dysfunction. This study focuses on intermediate survivors and provides important data for cancer care providers and decision makers in the field in the KSA.

Materials and Methods

This project was a cross-sectional study conducted among colorectal cancer patients diagnosed in the period from cancers survivors diagnosed between 1 January 2015 and May 2017, with the assessment conducted at 12 to 36 months after initial diagnosis. This would allow assessing intermediate and long-term consequences of colorectal cancer like pain, coping with a stoma, sexual problems, and psychosocial dysfunction. This study was not studying the immediate post-treatment effects of colorectal cancer management.

This study was conducted in three regions in the KSA: Central, Eastern, and Western. Research sites include three large tertiary Ministry of Health Hospitals and two National Guard Health Affairs hospitals. The sample in this study is expected to represent colorectal cancer survivors in the KSA to a large extent.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- Colon or rectal cancer patients between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2011

- Age range 18 to 65

- Lives permanently in the KSA

- No history of other cancers

- Not receiving current therapy for a minimum of six months prior to recruitment

Exclusion criteria:

- Inability to attend the interview

- Have a medical condition that limits her ability to complete interview

Study Outcomes

Primary endpoints:

• The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Colorectal module (QLQ-CR29)

The most widely used instrument is the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), which has been developed to assess the health-related quality of life of cancer patients (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer). This questionnaire was translated and validated in different languages, including the Arabic language (Awad et al., 2008). Moreover, few instruments have been specifically developed and validated for the assessment of the HRQL of colorectal cancer patients. the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR29) is one of the most widely used and validated tools specific for colorectal cancer (Whistance et al., 2009).

General psychological wellbeing using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a self-administered questionnaire to detect minor psychiatric impairment. This scale is a validated screening instrument for anxiety and depression that has been validated in different settings for the general population and patients with a wide range of medical conditions. A score of 0 to 7 is categorized as normal, a score of 8 to 10 suggests possible anxiety or depressive disorder, and a score of 11 or above indicates probable anxiety or depressive disorder (Zigmond and Snalth, 1983).

The hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) has been validated on patients with colorectal cancer (Tsunoda et al., 2005). It has also been validated on Arabic speaking patients (El-Rufaie and Absood, 1987).

Secondary Outcomes

• Interview questionnaire: This includes sociodemographic variables (age, age at diagnosis, time since last treatment, marital status, living status, average monthly household income, medical insurance, job, husband’s job, education, husband’s education, smoking status.

• Chart Review Form: This includes medical history, cancer treatment and diagnosis information: stage, grade, morphology, treatment, including categories for surgical treatment, systemic adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy), and radiation therapy. Menopausal status, other comorbidities, medication history, family history of cancer.

Methodology

Data were collected through a face-to-face interview and thorough chart review forms.

Eligible participants were interviewed alone by a research assistant unless they preferred to be accompanied by a friend or family member.

For illiterate patients, a third party such as a family member or a friend of the participant must be available when consenting

Scientific and ethics committees’ approvals

Scientific and Ethical approvals were obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs through King Abdullah International Medical Research Office. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to being interviewed.

Sample size calculation and data analysis

According to the Kish formula (1965) for survey sampling (Al-Subaihi, 2003), 112 is the estimated sample size with a margin error of 5%, which was representative of the estimated reported cases (1347) diagnosed in the KSA in 2014 (MoH, 2014).

Plan for statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using STATA 10 software. As shown in the study outcomes section, in addition to the calculation of quality-of-life scores, data on predictors of quality-of-life scores or confounding factors were collected through a standardized interview questionnaire and chart review form. These two questionnaires covered sociodemographic variables, pathology, stage, grade treatment, other medical conditions.

Student’s t tests was used to compare means of continuous variables for two groups, and one-way analysis of variance was used to compare means of continuous variables for three or more groups. For data that did not follow a Gaussian distribution, nonparametric tests was used (Bland, 2000).

Pearson correlation coefficients was used for investigating the relationship between two quantitative continuous variables. Chi-square tests was used to compare categorical measures, and a one-way analysis of variance was used to compare means of continuous measures across the groups. For the analyses that involved adjusting for covariates, forward stepwise logistic regression was used for dichotomous outcomes, and analysis of covariance will be used for continuous outcomes.

Results

The colorectal cancer is based on the results of 115 participants. The mean age was 53.3±11.6, while the mean age at diagnosis was 52.6±11.8.

55.8% of the participants are females. Other sociodemographic features are shown in supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Indicators for 115 Participants with Colorectal Cancer

| Number | Valid Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Site | ||

| Colon | 78 | 67.8 |

| Rectal | 21 | 18.3 |

| Rectosigmoid | 16 | 13.9 |

| Recurrent or first episode | ||

| First episode | 109 | 95 |

| Recurrent cancer | 6 | 5 |

| Presence of metastasis | ||

| Distant metastasis | 41 | 35.71 |

| Local | 55 | 47.96 |

| Regional | 19 | 16.33 |

| Type of surgery: | ||

| Local excision or simple polypectomy. | 7 | 5.97 |

| Resection and anastomosis. | 53 | 46.27 |

| Resection and anastomosis followed by chemotherapy. | 31 | 26.87 |

| Resection with or without anastomosis. | 10 | 8.96 |

| Surgery to remove parts of other organs, such as the liver, lungs, and ovaries, where cancer may have recurred or spread. | 14 | 11.94 |

| Chemotherapy therapy | ||

| No | 12 | 10.78 |

| Yes | 103 | 89.22 |

| Radiation therapy | ||

| No | 89 | 77.78 |

| Yes | 26 | 22.22 |

| Palliative Radiation therapy | ||

| No | 111 | 96.88 |

| Yes | 4 | 3.12 |

| Palliative chemotherapy | ||

| No | 102 | 88.3 |

| Yes | 13 | 11.7 |

| Stoma | ||

| Currently present | 17 | 14.94 |

| Not used | 81 | 70.11 |

| Used but removed | 17 | 14.94 |

Table 1 shows selected clinical indicators such as site, metastasis, treatment modalities ...etc.

67.8% of cases had colon cancer, 18.3% had rectal cancer, while 13.9% had rectosigmoid cancer. 95% of the participants had the first episode of colorectal cancer, while 5% had recurrent colorectal cancer.

This project showed alarming figures of low overall quality of life and impairment in the psychological wellbeing for intermediate colorectal cancer survivors (One to three years post-diagnosis) in KSA. The majority of the study participants had unexpectedly low global health score with a mean of 56.9±31.3SD, with 22.34% of participants scoring less than 33.3%. More than half of the sample had moderate to severe undiagnosed depression, and one third had moderate to severe anxiety. Only 3.7% of the sample received psychosocial support.

Results of the quality-of-life scores are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The QLQ-C30 questionnaires show that participants have unexpectedly low global health score with a mean of 56.9±31.3. The physical functioning scale had the lowest score of 61.3±27.7, while social functioning had the best scores with a mean of 79.3±26.5. Regarding the generic symptoms of cancer, fatigue was the worst symptom, followed by appetite loss.

Table 2.

QLQ-C30 Scores for Participants with CRC Cancer (n=115)

| Scale | Mean | Standard deviation |

Percent less than 33.3% | Percent more than 66.7% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health status | ||||

| Global health status/QoL (QL2) |

56.91 | 31.32 | 22.34 | 36.17 |

| Functional scales | ||||

| Physical functioning (PF2) |

61.33 | 27.71 | 10.62 | 36.28 |

| Role functioning (RF2) | 74.84 | 28.66 | 5.66 | 53.77 |

| Emotional functioning (EF) |

74.97 | 29.51 | 10.09 | 60.55 |

| Cognitive functioning (CF) |

75.45 | 28.44 | 6.36 | 58.18 |

| Social functioning (SF) |

79.32 | 26.46 | 2.78 | 60.19 |

| Symptom scales | ||||

| Fatigue (FA) | 37.02 | 30.39 | 39.82 | 12.39 |

| Nausea and vomiting (NV) |

23.3 | 30.34 | 61.06 | 7.96 |

| Pain (PA) | 30.24 | 29.76 | 50.44 | 8.85 |

| Dyspnea (DY) | 20.91 | 29.9 | 59.09 | 6.36 |

| Insomnia (SL) | 34.56 | 35.98 | 41.28 | 14.68 |

| Appetite loss (AP) | 36.11 | 35.63 | 37.96 | 14.81 |

| Constipation (CO) | 25.38 | 32.99 | 52.29 | 11.01 |

| Diarrhea (DI) | 22.94 | 33.24 | 58.72 | 11.01 |

| Financial difficulties (FI) |

16.01 | 28.81 | 70.59 | 5.88 |

Table 3.

Colon Cancer Module CR-29 for Colorectal Cancer Patients (n=115)

| Scale | Mean | Standard deviation |

Percent less than 33.3% | Percent more than 66.7% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional scales | ||||

| Body Image (BI) | 74.41 | 27.89 | 8.26 | 58.72 |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 58.65 | 38.72 | 20.19 | 37.5 |

| Weight (WEI) | 62.31 | 37.22 | 17.76 | 38.32 |

| Sexual interest men (SEXM) | 55.22 | 32.07 | 13.43 | 20.9 |

| Sexual interest women (SEXW) | 65.77 | 27.76 | 5.41 | 27.03 |

| Symptom scales | ||||

| Urinary frequency (UI) | 40.83 | 30.47 | 26.61 | 13.76 |

| Blood and mucus in the stool (BMS) | 15.12 | 24.7 | 72.22 | 2.78 |

| Stool frequency (SF) | 23.92 | 28.89 | 56.45 | 6.45 |

| Urinary incontinence (UI) | 12.96 | 24.89 | 74.07 | 2.78 |

| Dysuria (DY) | 18.69 | 29.02 | 63.55 | 5.61 |

| Abdominal pain (AP) | 31.46 | 33.9 | 43.93 | 10.28 |

| Buttock pain (BP) | 25.62 | 32.1 | 52.78 | 7.41 |

| Bloating (BF) | 25.96 | 31.14 | 49.04 | 7.69 |

| Dry mouth (DM) | 28.7 | 31.06 | 43.52 | 7.41 |

| Hair loss (HL) | 35.58 | 36.36 | 39.42 | 16.35 |

| Taste (TA) | 30.5 | 33.21 | 44.34 | 9.43 |

| Flatulence (FL) | 18.69 | 28.72 | 65.15 | 3.03 |

| Faecal incontinence (FI) | 20 | 30.51 | 63.08 | 6.15 |

| Sore skin (SS) | 20.9 | 32.22 | 64.18 | 7.46 |

| Embarrassment (EMB) | 25 | 38.49 | 65.62 | 15.62 |

| Stoma care problems (STO) | 18.42 | 31.67 | 68.42 | 7.89 |

| Impotence (IMP) | 41.03 | 35.24 | 29.23 | 16.92 |

| Dyspareunia (DYS) | 35.19 | 29.76 | 27.78 | 8.33 |

The colorectal cancer module results are shown in Table 3. showed that body image had the best and highest score, with a mean of 74.4±27.9. The worst score within functional scales was weight for females and sexual interest for males, while the worst reported symptom within the QLQ-C30 questionnaire was fatigue (mean score= 37.02) then appetite loss (mean score= 36.11). Symptom scale did not show a significant prevalence of symptoms amongst the study population, with all means less than 50. The proportion of participants with score percentage more than 66.7% was the highest for Impotence Symptom (16.9%) and Embarrassment (15.6%), followed by Urinary frequency (13.8%)

Psychological wellbeing assessment utilizing HADS reveals alarming outcomes for survivors of CRC in the KSA, as shown in Figure 1. A high proportion of participants with moderate to severe depression (55%) and a good proportion of participants with moderate to high anxiety (31%). Only 3.7% of participants reported receiving psychosocial support.

Figure 1.

Hospital Depression and Anxiety Score

Regression analysis

There were no statistically significant predictors for the global quality of life scores through the stepwise regression analysis. Regression analysis for predictors of HADS score showed that the statistically significant predictor for the HADS depression score was living status; for patients who live with husband or spouse had a lower depression scale than those living alone or with a family member. For anxiety score, the statistically significant predictor was the presence of metastasis; patients with metastasis have a higher anxiety score than those with local or regional disease.

Discussion

This project showed alarming figures of low overall quality of life and impairment in the psychological wellbeing for intermediate colorectal cancer survivors (One to three years post-diagnosis) in KSA. The mean global score of the QLQ-C30 (56.9±31.3SD) is slightly different and lower than that reported in regional and international figures; the mean global score in a study from Egypt was 64.5±11.9 SD (Hokkam et al., 2013), from Jordan (79.7±23.3 SD), (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014), and from Germany 62.8±22.4 SD (Arndt et al., 2004).18 Also, the mean global score in our study is worse than figures from recent two studies from the KSA with mean global scores of 67.1± 23.78SD (Almutairi et al., 2016) and 68.65±11.34SD (Younis, 2019).

The mean ages of participants in Egypt and Germany studies were 61.6±8.2 SD (Hokkam et al., 2013) and 65.0±9.9 SD (Arndt et al., 2004), respectively. While the Jordanian study that followed the same protocol of ours, the mean age of 53.3±11.6SD to close to that for our sample, although the quality of life in our study showed much worse scores when compared with the results from Jordan (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). There are slight differences between the Jordan study and our study in the stage of the disease (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). The proportions of patients distant metastasis is higher in this study, when compared with the Jordanian study. The proportion of cases with local, regional, and distant stages in the Jordan study were 47.4%, 40.5%, and 12.1%, respectively, while in our study, the rates were 47.96%, 16.33%, 35.71%, respectively. These differences could justify the worse scores amongst the Saudi population and indicates the need for early detection campaigns in the KSA.

The physical functioning scale had the lowest score, while social functioning had the best scores with a mean of, similar scores were reported from a German study (Arndt et al., 2004). Another single site study from the KSA showed that cognitive functioning was rated the highest with the mean value of 77.01±5.60, whereas emotional functioning scored the lowest with the mean value of 60.35±12.47, followed by social functioning 62.44±10.32SD (Almutairi et al., 2016).

In our study, the worst reported symptom within the QLQ-C30 questionnaire was fatigue then appetite loss Fatigue score is similar to that reported for German patients (35.4) (Arndt et al., 2004) but different in appetite loss score (9.8). For KSA patients, the mean score of the fatigue scale was (39.3) while the mean score of the loss of appetite scale was (29.13) (Younis, 2019). The mean score of the financial difficulties scale is better than that reported in Germany (20.9) (Arndt et al., 2004), but close to that reported in KSA, where the mean score was 17.2 (Younis, 2019).

The striking result in our study is that few of the participants participated in a psychosocial support group. Different studies have provided a strong evidence that psychosocial interventions are often efficacious in decreasing patients’ distress and improving their quality of life (Yun et al., 2013). In addition, participation in psychosocial support programs can often lead to the saving of resources (Lin et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, we did not perform a follow-up study on patients after diagnosis to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the quality of life of colorectal cancer patients in KSA. According to a 2014 report of the Saudi cancer registry, 24.4% of colorectal cases were localized tumors, 39.2% were regional, 29.1% showed distant metastasis, while the remaining 7.3% of the cases were labeled as unknown stage (MoH, 2014). This indicates that our sample is not different from the distribution of cases at diagnosis, and all stages are well represented in proportions relevant to this baseline distribution (Ramsey et al., 2000).

In KSA, there is no colorectal cancer control program, and initiatives for colorectal cancer early detection or screening are lacking. This could explain why around half of the study subjects had stage three or greater on TNM staging. This is consistent with results from other developing countries where such a program is not available (Safaee et al., 2012).

In our study, the worst reported symptom within the QLQ-C30 questionnaire was fatigue (mean score= 37.02) then appetite loss (mean score= 36.11). Fatigue score is similar to that reported for German patients (35.4) (Arndt et al., 2004) but different in appetite loss score (9.8). For KSA patients, the mean score of the fatigue scale was (39.3) while the mean score of the loss of appetite scale was (29.13) (Younis, 2019). The mean score of the financial difficulties scale (16.1) is better than that reported in Germany (20.9) (Arndt et al., 2004), but close to that reported in KSA, where the mean score was 17.2 (Younis, 2019). Variations in the cost of cancer treatment and differences in the social security system might alter the outcomes of this scale. In KSA, cancer patients receive free health insurance for cancer management.

As a consistent trend with the above findings, financial difficulties affected the global score and all physical scales of the QLQ-C30. Participants who were suffering from financial difficulties had worse scores in global health and all physical scales. These results are consistent with previous studies where patients with deprivation indicators had a poor quality of life (Loh et al., 2013).

For the QLQ-CR29 questionnaire, the worst scores within the functional scales were for sexual interest for men (mean= 55.22). Patient education and counseling are essential to improve the outcomes of this domain (Moriya, 2006). Regarding sexual interest in men, the results from Egypt and Jordan are similar to ours (Arndt et al., 2004; Hokkam et al., 2013; Abu-Helalah et al., 2014), while body image was the worst functional scale for Chinese patients (Peng et al., 2011). The scores for the QLQ-CR29 symptoms scales did not show significant prevalence amongst the study population, with all means less than 50. The proportion of participants with a score percentage more than 66.7% was the highest for Impotence Symptom (16.9%) and Embarrassment (15.6%), followed by Urinary frequency (13.8%). The worst scores for the QLQ-CR29 symptoms scales for this study were impotence followed by urinary frequency, then hair loss and dyspareunia. The worst scores for the QLQ-CR29 symptoms scales for the Jordan study were flatulence, impotence, and stoma care problems, the same results of the Egyptian study (Arndt et al., 2004; Hokkam et al., 2013; Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). In the Chinese study, impotence was the worst symptom, followed by fecal incontinence and dyspareunia (Ramsey et al., 2000). Patients who received palliative radiotherapy had a statistically significant worse dysuria score when compared with patients who did not receive it. The development of hemorrhagic cystitis secondary to radiotherapy could justify these findings (Chong et al., 2005).

The material status was considered the only marginally significant predictor in this study with (p-value= 0.057); this study showed that the married participant either male or female had a better global quality of life score. Results from the UK showed that sex, stage of the disease, symptoms, beliefs about consequences, lower income, and presence of other comorbidities were the main predictors for the quality of life scores (Gray et al., 2011).

For psychological wellbeing assessment using depression, anxiety, and the total HADS scores, our results show a high proportion of participants with moderate to severe depression (55%) and a good proportion of participants with moderate to high anxiety (31%). That is consistent with a recently published study from Jordan, where the proportion of participants with abnormal depression or anxiety scores was 18% and 23%, respectively (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). In a study from the United States, investigators used the Brief Symptom Inventory as a screening tool for anxiety and depression. That study showed prevalence rates of 35% for distress, 24% for anxiety, and 19% for depression (Zabora et al., 2001). A review of 15 studies published between June 1967 and June 2018 was conducted and showed that the prevalence of depression among patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer ranged from 1.6%–57%, and those of anxiety ranged from 1.0%–47.2%, indicating that there is a high prevalence of both depression and anxiety in colorectal patients, and these symptoms can persist even after cancer treatment is completed (Peng et al., 2019). Living with husband or spouse had a lower depression scale than those living alone or with a family member. This was consistent with Jordan study (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014).

Similar to the Jordan study, the result showed that anxiety scores were predicted by the following factors: the extent of disease, presence of social problems causing daily anxiety, low back pain, presence of other chronic diseases, reported diarrhea symptoms, hoarseness of voice, and HADS total score (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). A study conducted in the UK showed that patients with more advanced disease were more anxious and depressed, perceived their social support as lower, and had a worse quality of life with (P<0.01) (Simon et al., 2009).

The Value Of This Research To Cancer Care In The KSA

Results of this project reveal an overall trend of low scores of quality of life amongst colorectal cancer patients in the KSA when compared with regional or international figures (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014; Arndt et al., 2004; Faisal, 2018). Consistent results for psychological wellbeing were reached. There was a high prevalence of moderate to severe depression and anxiety when compared with regional data. We recommend routine screening for quality of life and psychological wellbeing and including the outcomes per individual patient care. Psychological support is highly needed for cancer survivors (Arndt et al., 2004; Hokkam et al., 2013; Abu-Helalah et al., 2014).

Similar to other studies from the Middle East, psychosocial support or counseling or referral to psychiatrists are limited for colorectal cancer survivors in the KSA (Abu-Helalah et al., 2014). High proportion of patients detected with advanced stage of CRC in the KSA highlight the importance of CRC programs in the KSA.

The results of this study will hopefully provide valuable data for colorectal cancer care providers in order to assess the outcomes of their management from patients’ perspectives. Detected impairment in any aspect of health-related quality of life or psychological wellbeing could help in the future management of colorectal cancer patients and hopefully stimulate further research in this field.

Author Contribution Statement

Munir Abu-Helalah: Proposal development, questionnaires and chart review forms development, project management, paper writing. Hani Mustafa: review project proposal, contributes to questionnaires and chart review forms development, data collection, review of the scientific paper and project management. Hussam Alshraideh: statistical analysis of the project. Abdullah Ibrahim Alsuhail: project local site PI, review the project proposal, local site PI. Omar A.Almousily: review project proposal, contributes to questionnaires and chart review forms development, review paper. Ruba Al-Abdallah: review questionnaires and chart review form, project coordinator, writing the first draft of the discussion in the paper. Ashwaq Al Olayan project local site PI, review the project proposal, local site PI.

Acknowledgements

Funding statement

This project was fully sponsored by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs.

Scientific Body Approval

This project was approved by the Scientific Committee at the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Eastern Region, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs.

Ethical Approval

This project obtained an ethical approval from the Central IRB Committee at the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs

Conflict of Interest statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest in this project.

References

- Abu-Helalah MA, Alshraideh HA, Al-Hanaqta MM, Arqoub KH. Quality of life and psychological well-being of colorectal cancer survivors in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7653–64. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.18.7653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ahwal MS, Shafik YH, Al-Ahwal HM. First national survival data for colorectal cancer among Saudis between 1994 and 2004: What’s next? BMC Public Health. 2013:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Subaihi AA. Sample size determination influencing factors and calculation strategies for survey research. Saudi Med J. 2003:24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi KM, Alhelih E, Al-Ajlan AS, Vinluan JM. A cross-sectional assessment of quality of life of colorectal cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016:18 . doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriole GL, Sandlund JT, Miser JS, et al. The efficacy of mesna (2-mercaptoethane sodium sulfonate) as a uroprotectant in patients with hemorrhagic cystitis receiving further oxazaphosphorine chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1987:5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: A population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2004:22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad MA, Denic S, El Taji H. Validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaires for Arabic-speaking populations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008:1138. doi: 10.1196/annals.1414.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM. An Introduction to Medical Statistics, 3rd edition. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caravati-Jouvenceaux A, Launoy G, Klein D, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Among Long-Term Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Oncologist. 2011:16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin F, Andreotti A, Zorzi M, et al. Usefulness of a fast track list for anxious patients in a upper GI endoscopy. BMC Surg. 2012:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-12-S1-S11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-12-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong KT, Hampson NB, Corman JM. Early hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves outcome for radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Urology. 2005:65. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rufaie OEFA, Absood G. Validity study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale among a group of Saudi patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1987:151. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.5.687. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.151.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Alami Y, Essangri H, Majbar MA, et al. Psychometric validation of the Moroccan version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in colorectal Cancer patients: cross-sectional study and systematic literature review. BMC Cancer. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07793-w. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07793-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal M. Assessment of quality of life of colorectal carcinoma patients after surgery. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S, et al. Modifiable and fixed factors predicting quality of life in people with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011:104. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain SG, Cataldo TE. Late stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008:21. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann BR. Early stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008:21. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1055318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY. Transition of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients on chemotherapy. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009:39. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2009.39.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WL, Sun JL, Chang SC, et al. Development and application of telephone counseling services for care of patients with colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014:15. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.2.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh KW, Majid HA, Dahlui M, Roslani AC, Su TT. Sociodemographic predictors of recall and recognition of colorectal cancer symptoms and anticipated delay in help-seeking in a multiethnic Asian population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013:14. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Clin Oncol. 2013:31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y. Function preservation in rectal cancer surgery. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006:11. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0608-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, et al. Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients’ quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology. 2010:19. doi: 10.1002/pon.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LH, Tsai YF. Quality of life in colorectal cancer patients with diarrhoea after surgery: A longitudinal study. J Clin Nurs. 2012:21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Shi D, Goodman KA, et al. Early results of quality of life for curatively treated rectal cancers in Chinese patients with EORTC QLQ-CR29. Radiat Oncol. 2011:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YN, Huang ML, Kao CH. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients: A literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019:16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SD, Andersen MR, Etzioni R, et al. Quality of life in survivors of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000:88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaee A, Fatemi SR, Ashtari S, et al. Four years incidence rate of colorectal cancer in iran: A survey of national cancer registry data - implications for screening. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012:13. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2695. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.6.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Küchler T, Longo WE, Kremer B. Ten-year historic cohort of quality of life and sexuality in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0822-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AE, Thompson MR, Flashman K, Wardle J. Disease stage and psychosocial outcomes in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01501.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financing Rev. 2008:29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steginga SK, Lynch BM, Hawkes A, Dunn J, Aitken J. Antecedents of domain-specific quality of life after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2009:18. doi: 10.1002/pon.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Tsunoda Y, Kusano M. Prospective analysis of quality of life in the first year after colorectal cancer surgery. Acta Oncologica. 2007:46. doi: 10.1080/02841860600847053. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860600847053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005:10. doi: 10.1007/s10147-005-0524-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-005-0524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009:45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younis M. Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients: Colostomies vs. Non-colostomies. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yun YH, Lee MK, Bae Y, et al. Efficacy of a training program for long-term disease-free cancer survivors as health partners: A randomized controlled trial in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013:14. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.12.7229. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.12.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001:10. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snalth RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;64:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]