Abstract

Aim: The aim of this study was to evaluate the attitude of Jordanian dentists towards the treatment of oral candidiasis and their current antifungal prescribing habits, shedding more light on the possible influence of their socio-professional factors on the pattern of prescribing and practice. Methods: A structured validated questionnaire was developed and tested; it was then emailed to a random sample of 600 Jordanian dental practitioners during the period of this cross-sectional survey. The questionnaire recorded practitioners’ personal details and their attitude and prescribing of antifungal therapy for oral candidiasis. Statistical significance was based on probability values of <0.05 and was measured using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to analyse the influence of respondents’ socio-professional factors on their attitude towards oral candidiasis. Results: Of the 423 questionnaires returned, only 330 were included. The attitude of respondents was significantly influenced by their experience [odds ratio (OR) = 0.14; P < 0.001] and workplace (OR = 4.70; P < 0.001). Nystatin was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent (78.2%), followed by miconazole (62.4%), which was prescribed for topical use. Systemic antifungals were prescribed by 21.2% of respondents, with a significant (P < 0.05) association with the country in which their qualification was obtained. Conclusion: The attitude towards the treatment of oral candidiasis is much better among the least-experienced dentists working in private practice. Nystatin and miconazole are the most popular choices of antifungal agents among Jordanian dentists.

Key words: Antifungal prescribing, attitude, Jordan, dentists

INTRODUCTION

Candida albicans is a normal finding in the oral cavity of the healthy population1. However, C. albicans has the potential to become problematic and pathogenic when its levels are increased or during exposure to single or multiple local and systemic factors, including environmental or host-dependent factors2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8.. Oral candidiasis is the commonest human fungal infection9, and candidal infections are currently by far the most commonly recorded fungal infections in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS)10. A recent study11 on Jordanian infants reported significant production of putative virulence enzymes of phospholipase and protease by most of the oral and rectal C. albicans isolates. Hence, if this infection is left untreated, it can lead to poor nutritional intake, speech impairment and prolonged recovery9., 12..

Epidemiological reports have indicated some changes in fungal infections between 2004 and 201413, namely a marked increase in their incidence, particularly those caused by Candida species10. Many key risk factors have contributed to the increasing incidence of opportunistic infections caused by Candida species, including: an increase in the incidence of diabetes mellitus; an increase in average life expectancies; the use of certain medications, such as broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressants; and certain immunodeficiency states, such as HIV positivity14. Furthermore, a high incidence of invasive Candida infections has been reported in intensive care unit (ICU) patients15., 16. following procedures such as abdominal surgery, organ transplantation and the placement of a central venous catheter. Hence, the use of different topical and systemic antifungal treatment modalities has been significantly increased. Unfortunately, antifungal drugs may be used inappropriately and this contributes to the worldwide increase in antifungal resistance, particularly to the group of azoles17., 18.. Also, resistance to antifungal therapy may be responsible for a wide range of adverse outcomes, including non-responsive infections, exposure of patients to ineffective medications and higher treatment costs19.

Generally, the patient’s immune state and type of pathology have to be considered when antifungal drugs are prescribed for the treatment of oral candidiasis. Topical treatment should be the first choice in immunocompetent patients, whereas systemic therapy is used as prophylaxis or for treatment of immunocompromised patients and for lesions not responding to topical treatment20. Furthermore, an Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America has recently prepared guidelines16 for the management of patients with invasive and mucosal candidiasis, and recommended the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis according to the severity of disease; topical therapy with clotrimazole or nystatin for mild infections; fluconazole for moderate-to-severe infections; and itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole or amphotericin B suspension for refractory infections. However, systemic treatment, unlike topical treatment, has the potential for greater adverse systemic effects, such as hepatotoxicity and interactions with other drugs21. Thus, the combination of topical and systemic treatment modalities would sometimes be advantageous for reducing the dose or duration of the systemic treatment22.

Antimicrobials are among the drugs most frequently prescribed by dentists23. Many studies have been conducted to investigate dental antibiotic prescribing23., 24., 25.. In Jordan, where this study was conducted, dentists’ antibiotic-prescribing practices were found to be less than ideal. Jordanian dental specialists had a tendency to overprescribe antibiotics23, and a substantial proportion of dentists had a tendency to prescribe long courses of antibiotics, as well as to prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics23., 25.. However, studies examining the attitude of dentists towards the treatment of oral candidiasis are scarce21 and the studies that are available show inconsistent methods in evaluating the influence of their socio-professional factors. A review of literature published in the last 20 years showed that only three studies investigated the attitude of dentists towards the treatment of oral candidiasis and their antifungal-prescribing habits: one was conducted in the USA, 20 years ago26; one was conducted in the UK, 10 years ago21; and a recent study was conducted in 2010 in Spain27. As far as we know, no such studies have been conducted in a developing country such as Jordan.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the attitude of Jordanian dentists towards the treatment of oral candidiasis and their current antifungal-prescribing habits, shedding more light on the possible influence of their socio-professional factors, including gender, workplace (private or public), and year (new or old graduates) and country (Jordan or other) of qualifications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

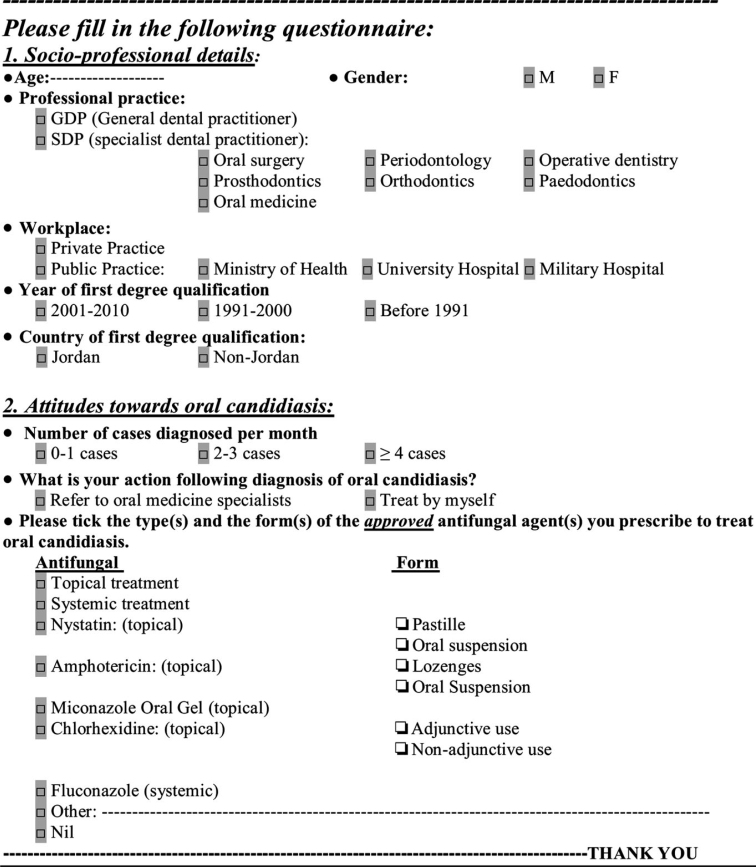

This cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted during the period 7 January 2013 to 31 August 2013. A constructed questionnaire was developed for the purpose of this study. It was written in English, recorded participants’ socio-professional details (including age, gender, workplace, professional practice and year and country of first degree qualification), their current prescribing habits of the available antifungal drugs approved to treat oral candidiasis in Jordan and their attitudes towards the treatment of oral candidiasis.

The initial draft of the questionnaire was prepared and included some items used in previous studies21., 26., 27.. The questionnaire was piloted and tested for clarity and simplicity of the items by being hand distributed to 10 dentists. Based on their comments, the questionnaire was modified and adjusted to make it easier for participants to understand and answer. The final questionnaire was then distributed to 20 participants. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested by asking the 20 participants to answer the questionnaire on another occasion, 1 week later. Kappa statistics were 0.91–0.95 for the items, indicating high reliability of the questionnaire.

The final form of the questionnaire (Figure 1) was sent by email and comprised the questionnaire as a separately attached file, and a cover page describing the study aims and objectives precisely, so that the survey was not interpreted as a monitoring exercise on the quality of care, which, if so, could bias the respondents’ answers. In addition, in the final paragraph of the cover page, practitioners were informed that ‘completing and returning the questionnaire is considered as written consent and agreement of participation’. A list of 1,200 dental practitioners, who were practicing dentistry over the period of the study, and for whom email access and other contact details were available, were obtained from the Jordan Dental Association (JDA). The questionnaire was emailed to a sample of 600 Jordanian dentists, randomly and systematically selected by choosing every second practitioner on the same list. Only two emails were sent: the first in January 2013; and the second, which was a follow-up email, approximately 2 months later to non-responders who might not use their emails regularly or to responders who returned questionnaires with incomplete responses. The questionnaire was anonymous – patient’s or respondent’s identity or confidential information were not disclosed or requested by any question. This study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Jordan.

Figure 1.

The questionnaire.

The SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software program was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics, frequency distributions and cross-tabulation were produced. Statistical differences between frequencies were measured using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the influence of participants’ professional details on their attitude towards the treatment of oral candidiasis. P <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 600 questionnaires were emailed to dental practitioners who were practicing dentistry in Jordan during the time period of this survey, and 423 dentists [general dental practitioners (GDPs) and specialist dental practitioners (SDPs)] responded and returned completed questionnaires (70.5% response rate). Of the 423 questionnaires returned, only 330 (78%) were included in the statistical analysis. The remaining 93 (22%) questionnaires were excluded: eight (1.9%) had a few questions that were not answered; 22 (5.2%) were returned by retired respondents; and 63 (14.9%) were returned by respondents who had postgraduate qualifications (i.e. were SDPs) in maxillofacial surgery (3.8%), oral medicine (1.9%), orthodontics (1.7%), operative dentistry (1.9%), prosthodontics (2.8%), pedodontics (0.9%) and periodontics (1.9%). Therefore, the basis for undertaking the percentage results was considering questionnaires with completed answers for each single question and only for GDPs.

The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of the 330 respondents included was 38.8 ± 10.0 [median (range): 37.0 (26.0–70.0)] years. There were 206 (62.4%) male respondents and 124 (37.6%) female respondents. The workplace for 194 (58.8%) respondents was private practice and for 136 (41.2%) was public practice – Ministry of Health (20%), university hospitals (9.7%) and Military Medical Services (11.5%). The majority of respondents (40.6%) graduated between 2001 and 2010, more than one-third (38.8%) graduated between 1991 and 2000, and the remaining 20.6% graduated before 1991. Lastly, the first degree qualification of 191 (57.9%) respondents was granted by Jordanian universities and by other countries for the remaining 139 (42.1%).

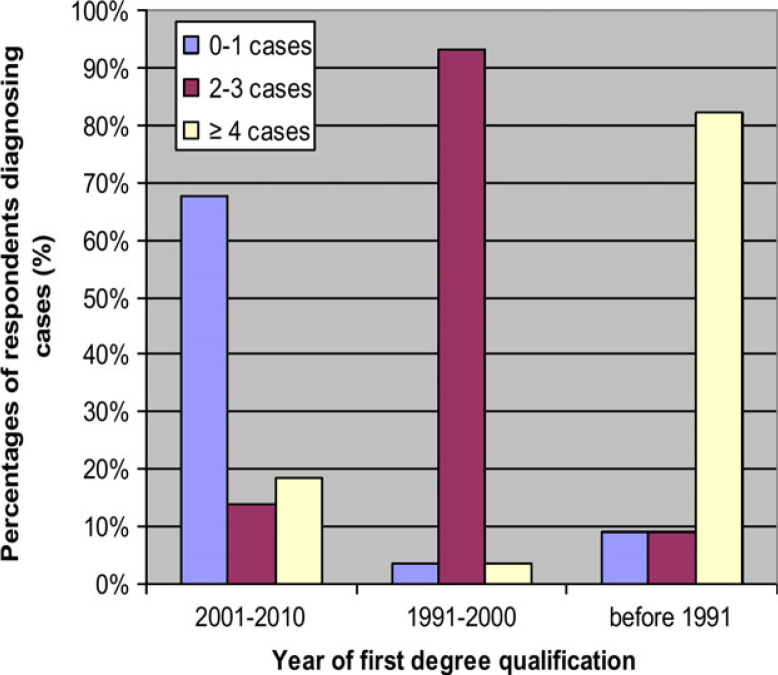

The participants reported the number of cases diagnosed with oral candidiasis each month in the last year; 0–1 cases were diagnosed by 185 (56.1%) respondents, 2–3 cases by 108 (32.7%) and more than three cases by the remaining 37 (11.2%). Therefore, the majority (88.8%) of dentists diagnosed a few cases of oral candidiasis (fewer than four) per month and only 11.2% diagnosed more than three. Male participants, those with Jordanian qualifications and those working in private practice diagnosed a higher number of cases (P < 0.01) compared with female participants, those with non-Jordanian qualifications and those working in public practice, respectively. Respondents’ year of qualification was found to have a significant (P < 0.001) association with the number of cases diagnosed per month; the fewest number of cases diagnosed (none or one) was commonly reported by dentists who graduated in 2001–2010, two to three cases were commonly reported by dentists who graduated in 1991–2000 and the highest number of cases (more than three) was commonly reported by older graduates (i.e. those who graduated before 1991) (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Number of cases of oral candidiasis diagnosed each month by participating dentists, stratified according to socio-professional factors (gender, workplace and year and country of first degree qualification) (n = 330)

| Socio-professional factors | Cases of oral candidiasis diagnosed per month |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 2–3 | ≥4 | Total | P* | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 121 (65.4) | 52 (48.1) | 33 (89.2) | 206 (62.4) | 0.001 |

| Female | 64 (34.6) | 56 (51.9) | 4 (10.8) | 124 (37.6) | |

| Total | 185 (100) | 108 (100) | 37 (100) | 330 (100) | |

| Workplace | |||||

| Private practice | 100 (54.1) | 64 (59.3) | 30 (81.1) | 194 (58.8) | 0.010 |

| Public practice | 85 (45.9) | 44 (40.7) | 7 (18.9) | 136 (41.2) | |

| Total | 185 (100) | 108 (100) | 37 (100) | 330 (100) | |

| Year of first degree qualification | |||||

| 2001–2010 | 134 (72.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 134 (40.6) | 0.001 |

| 1991–2000 | 24 (13) | 104 (96.3) | 0 (0) | 128 (38.8) | |

| Before 1991 | 27 (14.6) | 4 (3.7) | 37 (100) | 68 (20.6) | |

| Total | 185 (100) | 108 (100) | 37 (100) | 330 (100) | |

| Country of first degree qualification | |||||

| Jordan | 127 (68.6) | 64 (59.3) | 0 (0) | 191 (57.9) | 0.001 |

| Other | 58 (31.4) | 44 (40.7) | 37 (100) | 139 (42.1) | |

| Total | 185 (100) | 108 (100) | 37 (100) | 330 (100) | |

Calculated using the chi-square test.

Figure 2.

Cases of oral candidiasis diagnosed per month, according to the time period when the first degree qualification of respondents was obtained.

When participants were asked of their action following diagnosis of oral candidiasis in the last year, 282 (85.5%) reported that they treated it by themselves, whereas 48 (14.5%) referred patients to oral medicine specialists. Multivariate regression analysis (Table 2) identified two socio-professional factors that were significantly associated with the action taken by respondents (referral vs. treatment): the year of first degree qualification [odds ratio (OR) = 0.14, P < 0.001] was significantly related to respondents’ action of referral, suggesting that for every younger graduate (1991–2010) who referred patients, about 0.14 older graduates (before 1991) did so; and workplace differences were statistically significant (OR = 4.70, P < 0.001), in that respondents working in private practice tended to refer patients about five times more frequently than did those working in public practice. However, gender (OR = 0.68, P = 0.33) and country of first degree qualification (OR = 0.92, P = 0.86) did not affect respondents’ action of referral.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the influence of socio-professional factors on respondents’ decision to refer patients to oral medicine specialists following a diagnosis of oral candidiasis(n = 330)

| Variable | P* | Exp(B)(OR) | 95% CI for Exp(B) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowerbound | Upperbound | |||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.331 | 0.683 | 0.316 | 1.475 |

| Year of first degree (younger†vs. older‡) | 0.001 | 0.140 | 0.049 | 0.402 |

| Workplace (private vs. public) | 0.001 | 4.696 | 2.358 | 9.351 |

| Country of first degree (Jordan vs. other) | 0.855 | 0.919 | 0.371 | 2.279 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Calculated using the Wald chi-square test.

Graduated from 1991 to 2010.

Graduated before 1991.

Bold values indicate statistically significant at the 0.05 probability level (two-tailed).

The majority of respondents (85.5%) chose one or more than one type and/or form of antifungal in the last year. Prescription of topical antifungals was the choice of 292 (88.5%) respondents, whereas prescription of systemic antifungals was the choice of 70 (21.2%). Nystatin was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent (78.2%), followed by miconazole (62.4%), amphotericin B (13.3%) and fluconazole (10.9%). The use of chlorhexidine was reported by 72.7% of respondents; 93.2% reported its use as an adjunct to conventional antifungal agents (Table 3). Pastilles were the most popular form of the available intra-oral preparations of nystatin, and were prescribed by 93% of those prescribing nystatin, whereas 45.7% used the oral suspension. With regard to the amphotericin B preparations available, the most commonly prescribed form was lozenges, which was used by 81.8% of those prescribing amphotericin, with the suspension form being prescribed only by 27.3%.

Table 3.

Respondents’ choice of antifungal for treating oral candidiasis (n = 330)

| Antifungal agents | Prescribe n (%) | Not prescribe n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Topical treatment | 292 (88.5) | 38 (11.5) |

| Systemic treatment | 70 (21.2) | 260 (78.8) |

| Nystatin (topical) | 258 (78.2) | 72 (21.8) |

| Amphotericin (topical) | 44 (13.3) | 286 (86.7) |

| Miconazole Oral Gel (topical) | 206 (62.4) | 124 (37.6) |

| Chlorhexidine (topical) | 240 (72.7) | 90 (27.3) |

| Fluconazole (systemic) | 36 (10.9) | 294 (89.1) |

| Other | 4 (1.2) | 326 (98.8) |

The respondents’ choice of treatment of oral candidiasis with relation to their socio-professional details (including gender, workplace, and year and country of first degree qualification) is detailed in Table 4. Topical treatment was generally prescribed significantly (P < 0.05) more by male participants and younger graduates. By contrast, systemic treatment was generally prescribed significantly (P < 0.05) more often by respondents with Jordanian qualifications. However, one type of systemic treatment, fluconazole, was found to be (P < 0.05) prescribed significantly more often by male participants, younger graduates, respondents working in private practice and those with Jordanian qualifications.

Table 4.

Percentage differences in respondents’ choice of treatment for oral candidiasis, classified according to socio-professional factors (n = 330)

| Socio-professional factors | Prescribed treatment |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical treatment |

Systemic treatment |

Nystatin |

Amphotericin |

Miconazole |

Chlorhexidine |

Fluconazole |

Other |

|||||||||

| (n = 292) | P* | (n = 70) | P* | (n = 258) | P* | (n = 44) | P* | (n = 206) | P* | (n = 240) | P* | (n = 36) | P* | (n = 4) | P* | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male (n = 206) | 192 (93.2) | 0.001 | 50 (24.3) | 0.095 | 154 (74.8) | 0.055 | 24 (11.7) | 0.248 | 130 (63.1) | 0.815 | 156 (75.7) | 0.127 | 28 (13.6) | 0.046 | 0 (0) | 0.019 |

| Female (n = 124) | 100 (80.6) | 20 (16.1) | 104 (83.9) | 20 (16.1) | 76 (61..3) | 84 (67.7) | 8 (6.5) | 4 (3.2) | ||||||||

| Workplace | ||||||||||||||||

| Private practice (n = 194) | 175 (90.2) | 0.293 | 39 (20.1) | 0.586 | 146 (75.3) | 0.138 | 12 (6.2) | 0.001 | 120 (61.9) | 0.818 | 146 (75.3) | 0.258 | 36 (18.6) | 0.001 | 4 (2.1) | 0.146 |

| Public practice (n = 136) | 117 (86.0) | 31 (22.8) | 112 (82.4) | 32 (23.5) | 86 (63.2) | 94 (69.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

| Year of first degree qualification | ||||||||||||||||

| 1991–2010 (n = 262) | 242 (92.4) | 0.001 | 60 (22.9) | 0.182 | 214 (81.7) | 0.005 | 36 (13.7) | 0.842 | 175 (66.8) | 0.002 | 207 (79) | 0.001 | 36 (13.7) | 0.001 | 4 (1.5) | 0.585 |

| Before 1991 (n = 68) | 50 (73.5) | 10 (14.7) | 44 (64.7) | 8 (11.8) | 31 (45.6) | 33 (48.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

| Country of first degree qualification | ||||||||||||||||

| Jordan (n = 191) | 171 (89.5) | 0.491 | 52 (27.2) | 0.002 | 155 (81.2) | 0.139 | 16 (8.4) | 0.003 | 132 (69.1) | 0.004 | 155 (81.2) | 0.001 | 32 (6.8) | 0.001 | 4 (2.1) | 0.141 |

| Other (n = 139) | 121 (87.1) | 18 (12.9) | 103 (74.1) | 28 (20.1) | 74 (53.2) | 85 (61.2) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed).

Bold values indicate statistically significant at the 0.05 probability level (two-tailed).

DISCUSSION

The term ‘socio-professional details’ used in this survey has been described in a recent study27 and refers to the practitioner’s age, gender, workplace, professional practice, and year and country of first degree qualification. To the best knowledge of the authors, the present study is the first to investigate the influence of different socio-professional factors of Jordanian dental practitioners on their treatment of oral candidiasis and their antifungal-prescribing habits. The influence of country of qualification has not previously been considered in the literature. In the present study, only GDPs were included in the statistical analysis because the number of specialists, particularly in oral medicine, was small relative to the number of GDPs and this small number of SDPs would make any statistical analysis invalid. Although Arabic is the mother language in Jordan, English is the official language used by the Jordanian Medical Council in its examinations for medical and dental practitioners seeking to obtain their professional permit. Hence, writing the questionnaire in English is justified and considered suitable for all the study population. A response rate of 70.5% in this study indicates that the current antifungal prescribing pattern and attitude towards the treatment of oral candidiasis among Jordanian dentists are reasonably represented.

Dental practitioners may need to treat immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients who have different types of oral candidiasis, and regular oral care of patients with HIV is no exception28. However, a previous study showed that a substantial proportion of Jordanian dentists are reluctant to treat this category of patients29. Management of oral candidiasis entails identification and correction of the predisposing factor, wherever possible, and selecting the antifungal agent that is suitable for the patient and the lesion. Furthermore, weighing the risks and benefits of use of a specific antifungal agent has to be taken into consideration27., 30.. In this regard, dentists should have sufficient knowledge on the diagnosis of oral candidal lesions to permit prescription of the appropriate antimicrobial therapy. However, it has been reported that this knowledge and attitude may be influenced by the practitioners’ socio-professional factors, including gender, workplace and experience21., 27..

Regarding gender, a recent study reported that whereas the dental practitioners’ gender had no association with the number of patients diagnosed with oral candidiasis, male gender did have a significant influence on prescribing habits, particularly of systemic antifungal agents27. This is in contrast to the significant associations found in the present study in which male dental practitioners tended to diagnose a greater number of cases of oral candidiasis and preferred to prescribe topical antifungal agents. A possible explanation for this is that male dentists in Jordan work for longer hours, and have a heavier workload, than their female counterparts. Additionally, female dentists might have different educational experiences and practice opportunities that would influence their prescribing practices towards the less invasive topical treatment. This is consistent with other studies31., 32., 33., 34., 35., which reported that female dentists are less likely to work full-time and tend to see fewer patients.

The experience of dentists is known to have a significant association with their attitude and prescribing habits, particularly of systemic antifungal agents21., 27.. This is in agreement with the significant association found in the present study that as the experience of the respondents increased, the more likely they were to diagnose and treat oral candidal infections. Additionally, younger participants in this study tended to employ topical treatment, in general, and sometimes prescribed fluconazole significantly more often than did older participants. The international trends of teaching dentistry have changed over the last two decades; older dental graduates used to study dentistry, especially the first 3 years, in medical faculties along with medical students. However, dentistry is a different discipline from medicine and this has repercussions for dental education. Consequently, older graduates tend to show a number of tendencies, such as the self-confidence to prescribe systemic treatment and a higher capability to diagnose and treat fungal infections, which are different from those of younger graduates27. Furthermore, it has been reported that dentists with more experience tend to see more patients in their practices33, and this could be another explanation for the increased number of patients (more than three) diagnosed each month with oral candidiasis by our older graduates. Respondents with Jordanian qualifications used systemic antifungals significantly more often and diagnosed a greater number of cases of oral candidiasis. However, the country of qualification had no significant influence on the respondents’ decision following diagnosis (referral vs. treatment). Supposedly, the specialty of oral medicine in Jordan has shown major improvements in terms of the number of practicing specialists and new oral medicine specialty programmes. These specialists are mainly affiliated with academic institutions and this has reflected favourably on the quality of teaching of oral medicine in Jordanian universities in recent years, as evident (in the present study) by the increased use of topical agents and some systemic antifungals by younger graduates.

In this study, respondents working in private practice diagnosed and referred a greater number of patients compared with those working in public practice. However, the use of fluconazole was their significant choice when treatment was intended. This could be linked to the findings related to professional practice, which was not considered in this survey because of the small number of specialists, particularly in oral medicine. These findings indicate that this small number of oral medicine specialists in Jordan is mainly affiliated to public institutions. Therefore, GDPs working in public practice are expected to encounter many patients who have already been diagnosed and referred from private practice. However, GDPs working in Jordanian public practice have limited options in prescribing, and this was evident in their significant prescribing of amphotericin, which is commonly available in hospital practices only. In the same way, fluconazole was not considered as one of the significant prescribing options for GDPs working in governmental institutions such as the Ministry of Health, Military Medical Services and university hospitals. This is in contrast to a recent study27 that reported a non-significant association between the workplace of dentists and their attitude towards the treatment of oral candidiasis and their prescribing habits; however, the authors did not give an explanation for their findings.

Four antifungal drugs were preferred by participants in this study, namely (in descending order): nystatin, miconazole, amphotericin B and fluconazole. Nystatin was the most popular antifungal agent among the participants. It is also the drug most commonly prescribed by British dentists21; whereas, in Spain27, miconazole was found to be slightly preferred to nystatin. Generally, topical agents, such as nystatin, clotrimazole and miconazole, are the preferred first line of antifungal therapy for most patients30. However, topical drug therapy is often unsuccessful for many reasons, such as the necessity of frequent daily dosing; rapid oral clearance of the drug, which leads to insufficient contact time with the oral mucosa; the need for adequate salivary flow; the presence of decay-inducing sweeteners; and inadequate efficacy36. The same applies to nystatin, which has a recommended dosage of four times a day for 2 weeks or more. The use of nystatin is characterised by a decrease of the drug concentration to a subtherapeutic level fairly quickly after administration as a result of the rapid oral clearance of the drug37. Furthermore, the risk of dental caries is increased because of its sucrose content38. Some novel approaches that have been proposed to increase the efficacy of nystatin include nanonsisation39. On the other hand, nystatin and amphotericin B (polyene antifungals) show negligible absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and are widely used for the topical treatment of oral candidiasis37. In addition, resistance to these agents has rarely been reported40. Lastly, it was reported that amphotericin B can be better tolerated than nystatin41 and it is as effective as fluconazole for the treatment of denture-induced stomatitis42. Miconazole is among the early antifungals first introduced in the late 1960s37. Having both antibacterial and antifungal activities, it is theoretically the best antifungal to treat angular cheilitis37 and is an effective treatment for candida-associated denture stomatitis43. However, miconazole may potentiate the effect of warfarin14, and it should be avoided in pregnancy and porphyria37. This interaction of miconazole with warfarin may appear more significant when using systemic preparations21 of this and other antifungal agents, although, for oral lesions, miconazole is usually given in its topical form. On the other hand, a recent survey conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group reported that clotrimazole, nystatin and fluconazole were the most popular antifungals prescribed for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis44.

This study found that amphotericin B was the third most commonly prescribed drug by respondents, followed by fluconazole and other less commonly available antifungal agents, such as ketoconazole and itraconazole. This is in agreement with studies in some European countries, such as Spain27 and the UK21, in which fluconazole was amongst the least commonly prescribed agents. Fluconazole was introduced in 199036, and it is generally safe and well tolerated45. However, it may be associated with an increased incidence of birth defects46, proarrhythmic conditions47 and hepatotoxicity48. Whereas azoles, in general, interact with anticoagulants, fluconazole is contraindicated in liver disease and is implicated in liver dysfunction37. Although it has been demonstrated that fluconazole is very effective for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis, reports of resistance to this antifungal agent have been found13. Furthermore, certain non-C. albicans species, such as Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, show less susceptibility to fluconazole than other azole antifungals, and these are being recovered more frequently from patients with HIV49. Other antifungal agents, such as itraconazole and ketokonazole, were prescribed by a small proportion of respondents in this study and in a study conducted in Spain27. However, these agents were not available for dentists in the UK21. Fluconazole and itraconazole are better tolerated and more effective than ketoconazole50. Itraconazole has been reported to provide similar affectivity to fluconazole for the treatment of denture-induced stomatitis51. Indeed, among the oral azoles, fluconazole possesses the most desirable pharmacological properties, making it the drug of choice in the treatment of oro-pharyngeal candidiasis in HIV infection37.

Chlorhexidine mouthwash was used by a substantial proportion of participants in the present study and by others27. However, chlorhexidine was cited by only 5% of UK dentists21 as one of the treatment options other than the available conventional antifungal agents. The majority (93.2%) of our respondents who prescribed chlorhexidine, unlike dentists in the UK21 and in Spain27, reported its use as an adjunct to conventional antifungal agents, which indicates that they were selecting the appropriate drug therapies for fungal infections. Chlorhexidine belongs to the biguanide group and is active against a wide spectrum of microbial agents, including C. albicans. Therefore, it is widely prescribed by dentists to provide oral disinfection, particularly for denture wearers52. However, its adjunctive use with other antifungal agents is advocated53, although its simultaneous use with nystatin would result in a drug–drug interaction54. Recently, some antimicrobial agents, such as cetylpyridinium chloride, have been incorporated in some mouthwashes to provide greater activity against fungal infections.55.

Drug formulations preferred by our participants and by UK dentists21 were nystatin pastilles and amphotericin B lozenges. However, drug formulations were not considered in a study conducted in Spain27. Nystatin pastilles have a number of favourable properties (e.g. they can be sucked slowly and they have a sweetened formulation), which lead to a longer duration of action and better patient compliance37. They could be used successfully in HIV-infected patients as a prophylaxis against outbreaks or recurrence of oral candidiasis56. Amphotericin B was chosen according to personal preference by a small percentage of our participants, although this drug is not always available in the Jordanian pharmaceutical market.

The findings of this survey do stress the need for new models of education for future health professionals education and clinical management of oral candidiasis in Jordan. Although it is difficult to predict the effect of any changes to the dental curricula and to provide clear national guidance on the pattern of prescribing and practice for the treatment of oral candidiasis among future dentists, the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum should be enhanced with medical courses, such as oral microbiology and infectious diseases, delivered in a more comprehensive and productive way than at present. Other additional measures would include establishing oral medicine postgraduate training programmes to meet the requirements of the increasing numbers of patients with oral diseases. Furthermore, the JDA and other national health and academic agencies should provide clear guidance and training courses on the use of antifungals (amongst other antimicrobials) to all dental practitioners, regardless of their socio-professional background. In the light of the findings of this survey, there appears to be a significant influence of some socio-professional factors, such as experience, workplace and country of qualification, on the attitude of respondents and their prescribing pattern. Implementing clear guidelines at a national level, such as those of the Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America16 for the management of patients with invasive and mucosal candidiasis, would be highly recommended to guide practitioners in achieving an accurate diagnosis and prescribing safe and effective treatment. Consequently, we hope that the drawbacks of antifungal prescribing in Jordan will be overcome. Such guidelines have to be generated, taking into consideration the standard requirements leading to effective and safe management of oral candidiasis, in terms of clinical type, the patient’s medical condition, diagnostic skills, first- and second-line drugs, follow-up and documentation. This is again urgently needed in light of the data known on the importance of early detection of oral candidiasis, to prevent the development of invasive fungal infections and the associated high mortality rate16. Extra costs, as a result of prolonged hospital stay and greater use of hospital resources, will also be reduced. For instance, in the USA, a single hospital stay for the management of invasive candidiasis is estimated to be $40,00016., 57.. It is evident that Jordan now is in the middle of an unstable region politically with more immigrants coming from neighbouring countries and this generates more pressure on the health services, especially those provided by the Ministry of Health and armed forces hospitals, and primary care centres.

Despite the abovementioned results, this study is not without limitations. Differentiation between respondents prescribing antifungals simultaneously or those prescribing them according to the type of oral candidiasis, and between respondents prescribing antifungals as an initial first-line treatment or prescribing them after failure of the initial therapy, were not permitted by the design of the questionnaire. Similarly, the cost of patient care and the predisposing factors for oral candidiasis, such as denture wearing or some underlying systemic conditions, were not investigated. The exclusion of 93 completed questionnaires, the small sample size and the method of sample selection were additional limitations; it was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey and only dentists who were present in the practitioners’ list obtained from the JDA were selected. Therefore, future studies will have to incorporate a larger sample to provide findings that are nationally representative and able to confirm the results of this survey.

CONCLUSION

The attitude towards the treatment of oral candidiasis is more positive among the least-experienced GDPs who are working in private practice. Nystatin and miconazole are the most popular choices of antifungal agents among Jordanian dentists who showed proper treatment of oral candidiasis and adequate selection of recommended topical and systemic antifungal agents and formulations. Topical treatment is most commonly used among male GDPs and younger graduates, whereas systemic treatment is commonly used among dentists who graduated from Jordan.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the general and specialist dental practioners in Jordan who participated in this survey. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

CONTRIBUTION

Mohammad H. Al-Shayyab: correspondence, idea, hypothesis, study design, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, writing the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted and published. Osama A. Abu-Hammad and Najla S. Dar-Odeh: idea, hypothesis, substantial contributions to conception and design of and acquisition of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. Mahmoud K. AL-Omiri: substantial contributions to conception and design of and acquisition of data, consulted on statistical evaluation, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hibino K, Samaranayake LP, Hagg U, et al. The role of salivary factors in persistent oral carriage of Candida in humans. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon RD, Holmes AR, Masson AB, et al. Oral candida: clearance, colonization, or candidiasis? J Dent Res. 1995;74:1152–1161. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimoud AM, Lodter JP, Marty N, et al. Improved oral hygiene and Candida species colonization level in geriatric patients. Oral Dis. 2005;11:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuriyama T, Williams DW, Bagg J, et al. In vitro susceptibility of oral candida to seven antifungal agents. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2005;20:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein JB. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in the immunocompetent host. J Mycol Med. 1996;6:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abu-Elteen KH, Abu-Alteen RM. The prevalence of Candida albicans populations in the mouths of complete denture wearers. New Microbiol. 1998;21:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaremba ML, Dniluk T, Roxkiewicz D, et al. Incidence rate of Candida species in the oral cavity of middle-aged and elderly subjects. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon JP, da Costa SC, Totti VM, et al. Predisposing conditions for Candida spp. Carriage in the oral cavity of denture wearers and individuals with natural teeth. Can J Microbiol. 2006;52:462–467. doi: 10.1139/w05-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–459. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaller MA. Epidemiology of candidiasis. J Hosp Infect. 1995;30:329–338. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa SY, Badran EF, Aqel KF, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of Candida species colonizing oral and rectal sites of Jordanian infants. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migliorati CA, Madrid C. The interface between oral and systemic health: the need for more collaboration. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(Suppl 4):11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isham N, Ghannoum MA. Antifungal activity of miconazole against recent Candida strains. Mycoses. 2010;53:434–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farah CS, Lynch N, Mccullough MJ. Oral fungal infections: an update for the general practitioner. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(Suppl 1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kett DH, Azoulay E, Echeverria PM, et al. Candida bloodstream infections in intensive care units: analysis of the extended prevalence of infection in intensive care unit study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:665–670. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206c1ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rex JH, Rinaldi MG, Pfaller MA. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman M, Cloud GA, Smedema M, et al. Does long-term itraconazole prophylaxis result in vitro azole resistance in mucosal Candida albicans isolates from persons with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection? The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1585–1587. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1585-1587.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeffler J, Stevens DA. Antifungal drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:S31–S41. doi: 10.1086/344658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoppe J. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompetent infants: a randomized multicenter study of miconazol gel vs. nystatin suspension. The Antifungal Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:288–293. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver RJ, Dhaliwal HS, Theaker ED, et al. Patterns of antifungal prescribing in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2004;196:701–703. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viudes A, Peman J, Canton E, et al. The activity of combinations of systemic antimycotic drugs. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2004;4:30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dar-Odeh NS, Abu-Hammad OA, Khraisat AS, et al. An analysis of therapeutic, adult antibiotic prescriptions issued by dental practitioners in Jordan. Chemotherapy. 2008;54:17–22. doi: 10.1159/000112313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis MAO, Meechan C, Macfarlane TW, et al. Presentation and antimicrobial treatment of acute orofacial infections in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 1989;166:41–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dar-Odeh N, Ryalat S, Shayyab M, et al. Analysis of clinical records of dental patients attending Jordan University Hospital: Documentation of drug prescriptions and local anesthetic injections. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:1111–1117. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutkauskas JS. Drug prescription practices of hospital dentists. Spec Care Dentist. 1993;13:205–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1993.tb01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Beneyto Y, Lopez-Jornet P, Velandrino-Nicolas A, et al. Use of antifungal agents for oral candidiasis: results of a national survey. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton LL, Van Der Horst C. Oral infections and other manifestations of HIV disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:879–900. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Maaytah M, Al Kayed A, Al Qudah M, et al. Willingness of dentists in Jordan to treat HIV-infected patients. Oral Dis. 2005;11:318–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lalla RV, Patton LL, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Oral candidiasis: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment strategies. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2013;41:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Aguila MA, Leggott PJ, Robertson PB, et al. Practice patterns among male and female general dentists in a Washington State population. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:790–796. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walton SM, Byck GR, Cooksey JA, et al. Assessing differences in hours worked between male and female dentists: an analysis of cross-sectional national survey data from 1979 through 1999. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:637–645. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atchison KA, Bibb CA, Lefever KH, et al. Gender differences in career and practice patterns of PGD-trained dentists. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1358–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayers KM, Thomson WM, Rich AM, et al. Gender differences in dentists’ working practices and job satisfaction. J Dent. 2008;36:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newton JT, Buck D, Gibbons DE. Workforce planning in dentistry: the impact of shorter and more varied career patterns. Community Dent Health. 2001;18:236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darouiche RO. Oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in immunocompromised patients: treatment issues. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:259–272. doi: 10.1086/516315. quiz 273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellepola AN, Samaranayake LP. Oral candidal infections and antimycotics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11:172–198. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenspan D. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-positive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S51–S55. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melkoumov A, Goupil M, Louhichi F, et al. Nystatin nanosizing enhances in vitro and in vivo antifungal activity against Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2099–2105. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White TC, Marr KA, Bowden RA. Clinical, cellular and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Budtz-Jörgensen E, Lombardi T. Antifungal therapy in the oral cavity. Periodontol 2000. 1996;10:89–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1996.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bissel V, Felix DH, Wray D. Comparative trial of fluconazole and amphotericin in the treatment of denture stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1993;76:35–39. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90290-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dar-Odeh NS, Shehabi AA. Oral candidosis in patients with removable dentures. Mycoses. 2003;46:187–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vazquez JA. Therapeutic options for the management of oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in HIV/AIDS patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2000;1:47–59. doi: 10.1310/T7A7-1E63-2KA0-JKWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goa KL, Barradell LB. Fluconazole. An update of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in major superficial and systemic mycoses in immunocompromised patients. Drugs. 1995;50:658–690. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2061–2062. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1312226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chakravarty C, Singh PM, Trikha A, et al. Fluconazole-induced recurrentventricular fibrillation leading to multiple cardiac arrests. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:477–480. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egunsola O, Adefurin A, Fakis A, et al. Safety of fluconazole in paediatrics: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1211–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1468-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redding SW, Kirkpatrick WR, Dib O, et al. The epidemiology of non-albicans Candida in oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV patients. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20:178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2000.tb00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dismukes WE. Introduction to antifungal drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:653–657. doi: 10.1086/313748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cross LJ, Bagg J, Wray D, et al. A comparison of fluconazole and itraconazole in the management of denture stomatitis: a pilot study. J Dent. 1998;26:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meiller TF, Kelley JI, Jabra-Rizk MA, et al. In vitro studies of the efficacy of antimicrobials against fungi. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:663–670. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.113550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellepola ANB, Samaranayake LP. Adjunctive use of chlorhexidine in oval candidoses: a review. Oral Dis. 2001;7:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barkovv P, Attramadal A. Effect of nystatin and chlorhexidine gluconate on C. albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:279–281. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giuliana G, Pizzo G, Milici ME, et al. In vitro activities of antimicrobial agents against Candida species. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macphail LA, Hilton JF, Dodd CL, et al. Prophylaxis with nystatin pastilles for HIV-associated oral candidiasis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:470–476. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199608150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan J, Meltzer MI, Plikaytis BD, et al. Excess mortality, hospital stay, and cost due to candidemia: a case-control study using data from population-based candidemia surveillance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:540–547. doi: 10.1086/502581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]