Abstract

Objectives:

We aimed to describe emergency department (ED) care transition interventions delivered to older adults with cognitive impairment, identify relevant patient-centered outcomes, and determine priority research areas for future investigation.

Design:

Systematic scoping review.

Setting and Participants:

ED patients with cognitive impairment and/or their care partners.

Methods:

Informed by the clinical questions, we conducted systematic electronic searches of medical research databases for relevant publications following published guidelines. The results were presented to a stakeholder group representing ED-based and non-ED-based clinicians, individuals living with cognitive impairment, care partners, and advocacy organizations. After discussion, they voted on potential research areas to prioritize for future investigations.

Results:

From 3848 publications identified, 78 eligible studies underwent full text review, and 10 articles were abstracted. Common ED-to-community care transition interventions for older adults with cognitive impairment included interdisciplinary geriatric assessments, home visits from medical personnel, and telephone follow-ups. Intervention effects were mixed, with improvements observed in 30-day ED revisit rates but most largely ineffective at promoting connections to outpatient care or improving secondary outcomes such as physical function. Outcomes identified as important to adults with cognitive impairment and their care partners included care coordination between providers and inclusion of care partners in care management within the ED setting. The highest priority research area for future investigation identified by stakeholders was identifying strategies to tailor ED-to-community care transitions for adults living with cognitive impairment complicated by other vulnerabilities such as social isolation or economic disadvantage.

Conclusions and Implications:

This scoping review identified key gaps in ED-to-community care transition interventions delivered to older adults with cognitive impairment. Combined with a stakeholder assessment and prioritization, it identified relevant patient-centered outcomes and clarifies priority areas for future investigation to improve ED care for individuals with impaired cognition, an area of critical need given the current population trends.

Keywords: Care transitions, emergency department, cognitive impairment, patient-centered outcomes

Emergency departments (EDs) are an important resource for ill or injured older adults (age ≥65 years),1–4 with approximately two-thirds of ED visits resulting in discharge.5 Notably, up to 40% of older adults presenting to the ED have some degree of cognitive impairment,6–9 defined as either a short-term cognitive disturbance (eg, delirium), or a permanent neurodegenerative disorder (eg, dementia).3,4,6–13 Studies suggest older adults with cognitive impairment would benefit from improving the quality of the ED-to-community care transition.2,13–15 Defined as the transfer from an ED to a personal residence, independent, or congregate living settings, the “ED-to-community care transition” has less medical oversight, leading to greater vulnerability for patients with cognitive impairment.10,14 However the American College of Emergency Physicians’ ED Care Transitions Guidelines provide few recommendations to improve safety during this vulnerable period for this patient population.16 Consequently, this omission may contribute to unmet care needs,16 as well as the significantly higher rates of ED revisits, hospitalization, mortality, and subsequent health care costs observed for patients with cognitive impairment.6–10,14,15

Despite suboptimal care transition outcomes, little data exist on effective interventions to improve ED-to-community care transitions for older adults with cognitive impairment.9,15,17 Prior reviews of care transition interventions have focused predominantly on cognitively intact patients or transitions between non-ED settings.16,18 Few studies have specifically evaluated outcomes for older adults with cognitive impairment and/or their care partners.20–24 Among the barriers to this research is poor identification within ED settings.25,26 Prior work suggests that current ED screening strategies are underused by ED providers as the fast-paced, noisy ED environment can make accurate cognitive screening difficult.8,9,11,12,15,20,27 In addition, patient-centered outcomes of greatest importance to cognitive impaired older adults and their care partners have not been elucidated, limiting efforts to engage these stakeholders in research efforts to improve the ED care quality.28,29

The Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research 2.0 Network–Advancing Dementia Care (GEAR 2.0-ADC) infrastructure is a National Institutes on Aging (NIA)-funded effort to improve care for ED patients with dementia. This initiative includes stakeholders who identified ED-to-community care transitions for older adults with dementia as one of the 4 domains for investigation. The GEAR 2.0-ADC Care Transitions workgroup chose to expand the population of interest to more broadly include older adults with cognitive impairment because individuals with dementia are often not formally diagnosed, making it difficult to determine whether they have a short-term or a permanent cognitive disturbance. Further, from a practical standpoint, cognitive impairment impacts the care transition regardless of etiology.27 Thus, the workgroup worked to identify high-yield research questions related to care transitions for ED patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners through a systematic scoping review and consensus conference approach. This scoping review aimed to summarize the literature on ED care transition practices for patients with cognitive impairment and the priority gaps identified by stakeholders to address in future research.

Methods

Study Design

The Care Transitions workgroup conducted a scoping review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines.30 The workgroup included ED-based and non-ED based-clinicians, individuals living with dementia, care partners, and advocacy organizations. GEAR 2.0-ADC members were selected based on membership in national geriatric emergency medicine interest groups and/or through relevant publications in the GEAR 2.0-ADC domains.

We registered the scoping review protocol with the Open Science Framework (Registration DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/EPVR5).31 The Care Transitions workgroup developed 16 priority questions (Supplementary Table 1) during 6 monthly videoconference meetings. The full GEAR 2.0-ADC membership voted to identify the top 2 questions, which were then converted to the population-intervention-comparison-outcome (PICO) format32 and served as the basis for the scoping review: (1) Priority question 1: “What interventions delivered to ED patients with impaired cognition and their care partners improve ED discharge transitions?”; and (2) Priority question 2: “What measures of quality ED discharge transitions are important to varying groups of ED patients with impaired cognition and their care partners?”

Search Strategy

Article identification

We collaborated with a research librarian to comprehensively search the literature. The search combined controlled vocabulary and title/abstract terms related to care transitions for people with cognitive impairment in the ED-to-community settings, and included both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. We chose to focus on the ED-to-community care transition given that is the most common discharge setting for the population of interest, and one that has potential risk for adverse outcomes given the lack of ED guidance and support staff to assist with the transition.16

We adapted the search strategy from a GEAR 2.0-ADC baseline search strategy created jointly between librarians and project team members from the larger GEAR 2.0–ADC Network. The adapted search strategy was configured to fit the needs of our specific project questions and translated for the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase (OVID), CINAHL (Ebsco), PubMed (non-indexed citations), and Web of Science (Clarivate). We developed one search strategy for both PICO questions due to their similarity in scope. See supplementary materials for full details of search strategies. All searches were performed on March 25, 2021. No publication type, language, or date filters were applied. Results were downloaded to a citation management software (EndNote) and underwent automated deduplication. Unique records were uploaded to a platform (Covidence) for independent review by team members.

Conference proceedings from American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, and Alzheimer’s Association International Conference were manually screened for relevant abstracts, identifying 6 abstracts for inclusion. Twenty-four additional references were found by reviewing the literature referenced and recommendations of other team members.

Study selection and abstraction

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts from the search. Inclusion criteria for PICO-1 were interventions centered on ED discharge to the community setting (personal residence, independent congregate living, or assisted living facility) for adults 19 years of age or above with cognitive impairment and/or their care partner. We chose the term “care partner” to encompass both traditional caregivers and individuals who may share a reciprocal relationship with an adult living with cognitive impairment while co-managing care demands, as defined by the National Institute on Aging.33 Inclusion criteria for PICO-2 were adults 19 years of age or older with cognitive impairment and/or their care partner providing input on measures of ED-to-community care transitions. Exclusion criteria for both PICO questions included patients that were transferred or admitted to the hospital, as well as those with stroke, traumatic brain injury, alcohol, or case study categorization. Retained abstracts were elevated to full text screening for consideration of inclusion in the review. Adjudication occurred via consensus between 2 authors (MS, LH). The primary authors were contacted via email for clarification if study results did not explicitly mention outcomes for the subset of patients with cognitive impairment. This occurred for 22 potential papers, with 19 of the primary authors being able to be contacted. None of the authors published further studies explicitly analyzing patients with cognitive impairment.

Two authors (J.F., C.G.) abstracted data from the final articles including study setting, participant demographics, race/ethnicity, and inclusion/exclusion criteria amongst other information. The PICO-1 template additionally included primary and secondary intervention outcomes, the outcome effect and size and feasibility, acceptability, safety and other measures of success or failure of the interventions. For PICO-2, authors collected patient, care partner, and utilization measures of quality ED discharge care transitions.

Literature Assessment

We presented the scoping review results to the full Care Transitions workgroup for critical analysis, to identify the gaps in the field, and to provide direction for future research. The workgroup developed five research priorities for consideration at the GEAR 2.0-ADC Consensus Conference. During the Consensus Conference, participants were split into 4 equal, transdisciplinary groups to discuss the literature findings and identify perceived research gaps not addressed in the proposed research priorities. The resulting conclusions were then synthesized by the Care Transitions workgroup to form the final research priority items. All stakeholders at the GEAR 2.0-ADC Consensus Conference then voted on these items to establish ranked priorities for future investigation.

Results

Abstraction Process

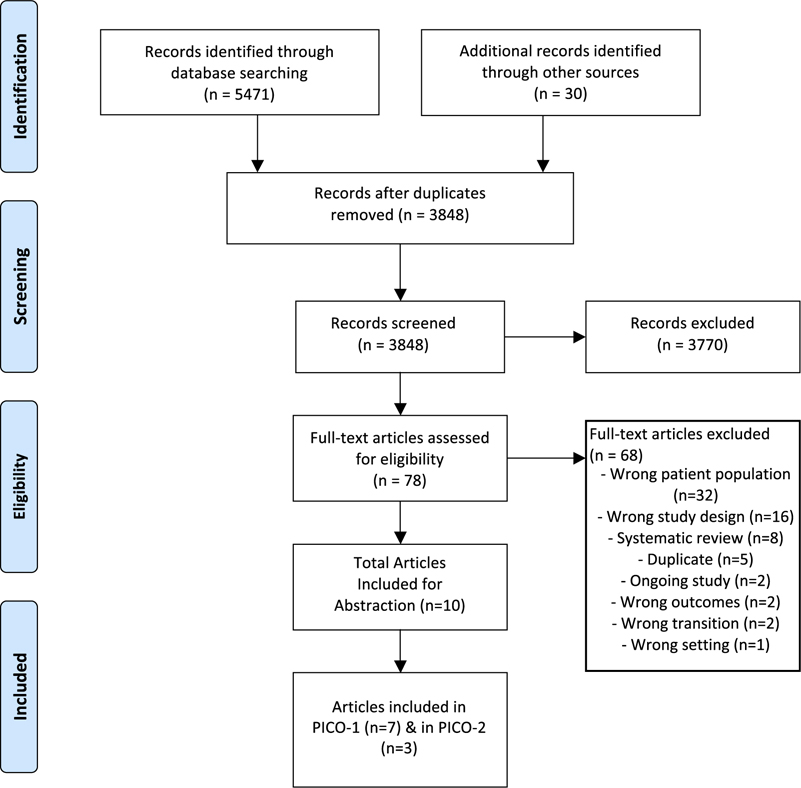

The search identified 5471 citations; 1623 duplicates were removed, and the remaining 3848 unique studies’ titles and abstracts were screened using the study criteria. The inter-rater reliability during the title and abstract screening was weak (k = 0.26), but improved during the full screening process (k = 0.38).Although 78 articles advanced to full text screening, 68 were subsequently excluded for not meeting study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Seven studies related to PICO-1, and 3 studies related to PICO-2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection and abstraction process for the current scoping review.

PICO-1

Participant characteristics

The 7 studies had over 2500 participants from 7 countries.34–40 The participation rate of individuals with cognitive impairment ranged from 3% to 100%,34–40 with 2 studies targeting cognitively impaired ED patients.35,40 The mean age of study participants ranged from 78 to 87 years, and the majority of participants were female.34–40 No study reported the racial or ethnic backgrounds of study participants. One study restricted participation to those with specific medical diagnoses (eg, heart failure),37 and another was limited to only patients with specific risk factors for ED revisit (eg, poor social support).34

Study characteristics

Of the 7 studies, 1 was a conference abstract (prospective cohort study),39 2 were prospective cohort studies,34,38 1 was a retrospective cohort study,35 2 were randomized control studies,36,40 and 1 was a quasi-randomized clinical trial.37

Interventions

There was substantial heterogeneity in the interventions delivered across studies. Five studies included comprehensive geriatric assessments or exposure to geriatric-specific ED services such as assessments of vulnerabilities, physical function, polypharmacy, multimorbidity, and/or social supports.34,35,37–39 Other intervention elements within multiple studies included enhanced discharge planning (eg, follow-up visits) and referrals to primary care or specialist services.34–38,40 The remaining study had trained community paramedics make home visits.40

Three studies delivered interventions primarily in the ED/hospital,35,38,39 one primarily in the home setting,40 and the remaining 3 used a mix of home and community follow-ups.34,36,37 Multiple personnel were involved in intervention delivery, including geriatric trained physicians,34,35,37,38 case management staff (eg, social workers),34–36 nurses,34,35,37 and occupational therapists.39 The intensity of the intervention was poorly described across most studies, with some studies including a single geriatric assessment,35,37,38 a single follow-up phone call after discharge,38 and others describing a general pattern of visits delivered as needed but with few details.34,36,39 One study included an in-person visit and up to 3 phone calls in the 30 days following discharge.40

Study outcomes

Of the 7 studies, 1 only reported patient outcomes but did not have a comparison group or timeframe.38 Five studies explicitly measured ED revisits as a primary or secondary study outcome–most included a 30-day time point,35,37,39,40 but studies also assessed ED revisit rates at 14 days40 and 3 months.34 The primary outcome in 1 study was adherence to outpatient recommendations,38 and another used a continuous measure of days spent at home in the 90 days following discharge.36 Secondary study outcomes varied across studies, and included functional status, mortality, quality of life, patient satisfaction, falls, and hospital admission rates.34–38

Of the studies that measured ED revisits as a primary outcome, all showed a decline in revisit rates in the intervention arm compared with usual care or the preintervention time period.34,35,37,39,40 The largest decline, a 75% reduction in the odds for 30-day ED revisit (95% confidence interval 10%−93%), was observed in a study led by Shah et al in which interventions were led by trained community paramedics.40 However, they found no significant difference in ED revisits rates at 14 days.40 Ballabio et al determined that geriatrician-led interventions with longer revisit timeframes led to a significant 9% absolute reduction in ED revisit rates (95% confidence interval 2%−16%).34 The impact of interventions on secondary outcomes was generally weaker, with studies showing either no improvements or marginal improvements on outcomes of interest.34–38 (Tables 1 and 2 provide more details.

Table 1.

Synthesis of Scoping Review Literature

| PICO-1 | PICO-2 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Summary | Population: Adult (≥19-y-old) ED patients from any home (SNF, home, etc) setting with impaired cognition (diagnosed dementia, delirium, positive cognitive impairment screen or noted confusion by the provider) AND/OR their care partner (defined as any individual caring for the patient, whether paid or unpaid). Intervention: Any intervention occurring in the discharge phase of ED care directed at any level (medical system, physician, direct to patient). Comparison: Standard of care as defined by study authors; between individuals with and without impaired cognition. Outcomes: Patient related (eg, quality of life, satisfaction, experience), care partner (eg, satisfaction, experience), utilization (eg, ED revisit, PCP follow-up, hospitalization, cost/medical expenditures). |

Population: Adult (≥19-y-old) ED patients from any home (SNF, home, etc) setting with impaired cognition (diagnosed dementia, delirium, positive cognitive impairment screen or noted confusion by the provider) AND/OR their care partner (defined as any individual caring for the patient, whether paid or unpaid). Intervention: N/A Comparison: Between different types of patient characteristics (eg, race, ethnicity, rural/urban, living arrangement, etc) as well as patients and their care partners. Outcomes: Importance of measures in all domains including patient related (eg, quality of life, satisfaction, experience), care partner (eg, satisfaction, experience), utilization (eg, ED revisit, PCP follow-up, hospitalization, cost/medical expenditures). |

| Number of Included Studies | 7 | 3 |

| Prospective/Retrospective Cohort Study, n (%) | 4 (57) | 1 (33) |

| Randomized/Quasi-Randomized Control Trials, n (%) | 3(43) | N/A |

| Qualitative Analyses, n (%) | N/A | 2 (67) |

| Interventions/Instruments utilized (n) | Medication review (2) Follow-up assessment (6) Initial assessment by geriatrician (5) Care planning (6) Community services (4) |

23 Quality indicators (1) |

| Total number of patients recruited | 3013 | 690 |

| Recruitment period | 2008–2021 | 2015–2020 |

| Geographical locations | 7 countries | 3 countries |

| Mean age range (y) (n) | 78–87 (7) | 80.3–83 (2) Unreported (1) |

| Common inclusion criteria (n) | Age 60 y and older Admitted and eligible for discharge from the ED Scored 2 or higher on senior at risk tool (1) Cognitive impairment (3) |

Age 65 y and older Presenting to the ED (2) Recently discharged from hospital/ED Health care provider directly involved in medication management (1) |

| Patient-centered primary outcomes (n) | Mobility improvements/functional gains (2) Adherence to outpatient follow-up recommendations (1) | N/A |

| ED-centered primary outcomes | Readmission rates within 30 d (6) | NA |

| Secondary outcomes | Length of initial hospital stay (1) Patient satisfaction (1) ED revisits within 14 d (1) Incidences of hospitalization after first admission to ED (2) Mortality (2) |

N/A |

| Follow-up period post-ED discharge | Three d–6 wk | N/A |

| Patient reported measures (n) | N/A | Problems in medication management (1) Feeling overwhelmed (2) Loss of independence (1) Fear of falling (1) Need for screening, risk/pain assessment, medical history, ED length of stay (1) |

| Care partner measures (n) | N/A | Safety and cost of SNFs/long-term care (1) Communication between care partner and care provider (2) Nonspecified (1) |

| Utilization measures | N/A | Follow-up with PCP (1) Referrals for follow-up evaluation of cognitive status (1) |

PCP, primary care physician; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included PICO-1 Individual Care Transition Intervention Studies

| Author Location Year | No. Patients (Mean Age) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Study Design | Intervention Type | Primary Outcome(s) | Secondary Outcome(s) | Outcomes/Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Ballabio34 Italy 2008 | 222 (83.5) | Age ≥75y and at least 1 of the following: impaired physical/functional status; daily intake of 3+ drugs, ≥3 chronic conditions, living alone, or lacking adequate social support. | Referral from a nursing home | Prospective observational cohort of older adults consecutively admitted to the ED and followed for 3 months; comparison to historical controls. | Initial assessment by onsite geriatrician with referral for CGE to be completed within 72 h at the outpatient geriatric unit. Evaluation was performed by a geriatrician, nurse, and social worker. Subsequent individualized care plan communicated to pCp. Explored 8 domains: medical conditions, medications, access to care, functional and nutritional status, social situation, and cognitive and emotional status. | No explicit delimitation of outcomes. Looked at readmissions to the ED 3 mo following CGE. Also 3-mo follow-up scores for evaluation for physical status, mini-nutritional assessment scale, functional status, cognitive status, depression, CG stress, and perceived QOL | NR | Significant improvement in NpI, NpI-d, Cornell, GDS, MNA, and EuroQuol scores 3-month follow-up compared with baseline assessment. Significant reduction in the number of patients with ED revisits during the 3-mo follow-up timeframe compared with the 3-mo period before the comprehensive geriatric evaluation: 11% readmitted after CGE compared with 20% before, 9% absolute difference (95% CI 2%–16%). |

| Bosetti35 France 2020 | 801 (87.0) | Age ≥ 75 y, previously diagnosed with neurocognitive disorder (DSM V criteria) and comorbidities admitted to the ED between 8:30 am and 6:30 pm Monday-Wednesday. | prior ED admissions within the study, admission for a vital or surgical emergency, admission outside working hours, and patients who were transferred to another hospital after being released from the ED or died before discharge; daytime hours 8:30 am-6:30 pm. | Historical cohort study of patients treated in either the GEMU (exposed) or provided normal care by ED physicians (control). | Exposure to GEMU: assessments by nurse (autonomy, deficiencies, neurosensory disorders, and lifestyle), geriatricians (acute pathology, comorbidities, screening of geriatric syndromes, and regular treatment), and social workers (identifying vulnerable social situation). Team developed individualized healthcare plan, recommended additional assessments, and guided patients in selecting care facilities and home care services. Standard care defined by care provided by ED physicians. | 30-d readmission rate. | Incidence of hospitalizations after the first admission to the ED. | 57.8% were hospitalized after ED admission in the exposed group vs 47.1% in the control group; 15.8% were readmitted after discharge in exposed group vs 22.2% in the control. OR for primary outcome of 30-d readmission: 0.65 for GEMU vs control, 95% CI 0.46–0.94). For secondary outcome of hospitalization rate, OR was 1.39 for GEMU vs control (95% CI 1.05–1.85). |

| Edmans36 UK 2013 | 433 (82.8) | Discharged from an acute medical unit within 72 h of attending the hospital, ag ≥70 y, and a score of at least 2/6 on ISAR tool. | Not residing in resident catchment area, lacking mental capacity to give consent and lacking a legal proxy, exceptional reason given by medical staff about exclusion from study, and participation in related studies. | RCT; recruitment took place with embedded researchers in the acute medical unit. | Interventions included review of diagnoses; a drug review; further assessment at home or in a clinic or by recommending admission rather than discharge; advance care planning; or liaison with primary care, intermediate care, and specialist community services. Control group received usual care. | Days spent at home in the 90 d after randomization. | Death; institutionalization; total count of combined inpatient admissions, ED visits, and d cases during 90-d follow-up; dependency in ADLs, self-reported falls, psychological well-being, and health-related QOL. | Mean count difference for primary outcome was −0.5 d at home between intervention and control (95% CI −4.6 to 3.6); death hazard ratio 1.22 (95% CI 0.57–2.65); institutionalization hazard ratio 1.31 (95% CI 0.34–4.97); rate ratio for difference in count of hospital presentations 1.32 (95% CI1.01–1.74); OR for ADL index ≥17 was 1.25 (95% CI 0.72–2.17); difference in log-transformed mean GHQ-10 score was 0.96 (95% CI 0.87–1.06); difference in mean EQ-5D scores was −0.01 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.06); odds ratio for an ICECAP-O score ≥0.81 was 1.38 (95% CI 0.80–2.40); OR for self-reported falls during follow-up was 0.94 (95% CI 0.60–1.48). No difference in number of d spent at home between control and intervention groups (P = .31); increased hospitalization presentation in intervention group compared with control group (P = .05); no significant differences in secondary outcomes. |

| Pedersen37 Denmark 2016 | 1330 (86.4) | Age ≥75 y, admitted to ED with pneumonia, COPD, delirium, dehydration, UTI, constipation, anemia, heart failure, or other infections. | Terminal diagnoses, already in a geriatric follow-up program, living outside the municipality, or transferred to another hospital department. | Quasi-RCT of older adults recruited within 24 h of ED admission. Study interventions occurred Monday-Friday. | CGE by a geriatrician and a nurse or therapist trained in geriatric homecare. Visit on next weekday after study enrollment. Interventions were tailored to patient needs, and patients were encouraged to follow-up by phone directly with questions. | Readmission rates within 30 d of discharge. | Discharge to home R rates; hospital LOS; number of d maintaining contact with geriatrics team; follow-up screening after ED discharge; 30-dmortality. | Readmission rate 12% for intervention and 23% for control with hazard ratio 0.49 (95% CI 0.37–0.64) favoring intervention; 56% of intervention patients discharged home vs 49% of controls (P = .01); median hospital LOS 2 (IQR 1–7) for intervention vs 3 d (IQR 1–8 days), P = .03; median time in contract with geriatric team 14 d (IQR 8–24 days) intervention group vs 1 d(IQR 1–5 d) for control; intervention group follow-up rate 73% within 24 h and 96% within 3 d compared with control group overall rate of 44%; 30-dmortality did not significantly differ between intervention (12%) and control (14%); hazard ratio for intervention vs control was 0.96 (95% CI 0.78–1.18), with P = .25. |

| MacDonald3 Canada 2019 | 8 103 (83.1) | Convenience sample of patients age ≥65 y who underwent assessment by the GEM nurse (by phone or in person), and referred for further outpatient evaluation by specialty geriatric services. | Not referred for specialized geriatric services; did not provide consent or admitted to the hospital. | Prospective cohort study of ED patients. | Focused geriatric assessment of mood, cognition, mobility, home function, CG issues with subsequent recommendations and referrals to SGS. Telephone follow-up at 6 weeks. | Adherence to outpatient follow-up recommendations of specialized geriatric services. | Patient satisfaction; 5 barriers and facilitators to follow-up. | 1.18), with P = .25. 9.2% attended outpatient services including geriatric d hospital (57.7%), geriatric assessment outreach team (81.5%), falls clinic (46.2%), geriatric psychiatry community services of Ottowa (22.2%) and memory program (50%); 58.9% reported they were satisfied. |

| O’Riordan39 Ireland 2017 | 43 (NR; 50% were 8089 y) | Frail patients being discharged home from the ED, virtual ward or inpatient wards. | NR | QI project, prospective cohort study of older adults receiving early rehabilitation and case management after ED discharge. | Integrated Care Service: occupational therapy visits, facilitated discharge support with case management, rehabilitation and referrals for PCP follow-up. | Readmissions, mobility improvements/fall risk, and functional gains as measured by the FIM. | NR | 3/43 patients readmitted within 30 d; 86% had improved mobility and/or reduced fall risk postintervention, 67% had improved FIM scores (made functional gains), and 1/3 maintained functional status. |

| Shah40 US 2021 | 81 (78.0) | Communitydwelling older adult (age ≥60 y) with PCP in health care system where study was conducted, discharged to the community, and with cognitive impairment (BOMC Test score of >10). | Receiving care management or hospice services. | Study was a preplanned subanalysis of a singleblind RCT testing effectiveness of adapted CTI. Patients were identified during ED visit and randomized to control (usual care) or intervention groups. | Home visit from a trained paramedic coach within 72 h of ED discharge, and up to 3phone call follow-ups over the subsequent 30 d following ED discharge. | ED re-visits within 30 d of discharge. | ED re-visit within 14 d of discharge; outpatient clinic follow-up visit attendance. | OR and 95% CI for 30-d revisit was 0.25 (0.07–0.90), for 14 d revisit was 1.01 (95% CI 0.26–3.93), and no significant effect was reported for outpatient follow-up. |

ADL, activities of daily living; BOMC, Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration; CG, caregiver; CGE, comprehensive geriatric evaluation; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTI, care transitions intervention; ED, emergency department; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; GDS, geriatric depression scale; GEMU, geriatric emergency medical unit; ISAR, identification of seniors at risk; LOS, length of stay; MNA, mini-nutritional assessment; NPI, neuropsychiatric inventory; NPI-d, neuropsychiatric inventory distress; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PCP, primary care provider; QI, quality improvement; QOL, quality of life; RCT, randomized clinical trial; UTI, urinary tract infection.

PICO-2

Participant characteristics

The 3 included studies had 690 total patient or care partner participants from 3 countries.41–43 One study reported the sex breakdowns of patients with and without cognitive impairment separately (46% and 50% female, respectively).43 Gettel et al reported 64% of participants were female and that 83% of care partners were female.42 No study recorded the racial or ethnic backgrounds of study participants. Two studies restricted the inclusion to participants who spoke native language(s) of their country of origin,41,42 and 1 study allowed any participation if a translator could be located within 2 hours.43 Among the 2 studies that noted the participation rate of individuals with cognitive impairment, 199 persons were represented.42,43 In the 2 studies that reported age, the mean ranged from 80 to 83 years.42,43

Study characteristics

Of the included studies, all 3 were original research articles. Two were qualitative studies41,42; 1 study used focus group methodologies with patients to specifically discuss concerns with medication management during care transitions,41 and the second used individual interviews with patient, care partners, or patient-care partner dyads embedded within a larger randomized clinical trial.42 The third study by Schnitker et al included patients and care partners in 2 phases.43 First, a stakeholder advisory board was convened to propose outcome measures to be used for patients with cognitive impairment during ED visits. Care partners subsequently voted on measures that had been field-tested on a separate sample of older adults with cognitive impairment within the ED.

Outcomes of greatest importance to patients and care partners

A wide array of outcomes important to patients and their care partners were identified, with specific attention paid to medication changes, communication techniques, functional independence, and costs. Participants in one study noted a number of concerns with communication about medication safety and medication changes during and after ED visits.41 Participants with cognitive impairment cited concerns over inadequate assessment of physical and cognitive limitations to medication management (eg, impaired dexterity or memory concerns).41 Patients and care partners also reported feeling overwhelmed with the burden of information and self-care required during ED-to-community care transitions, potentially contributing to poor rates of follow-up with other healthcare providers.41,42 Loss of independence, home safety, costs of long-term care, and fear of falling were also reported as concerns from patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners.42

Patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners identified several outcomes to be important during ED-to-community care transitions. Specifically, both groups recommended that education be provided regarding newly prescribed medications, including common adverse reactions.41,42 Care partners further recommended that a way to measure the quality of communication between care partners and providers about medications may be important.42 Measuring how frequently care partners were notified or contacted during an ED visit was suggested,41,42 and formal involvement of the care partner in history-taking and care decision planning were also considered crucial.43 Other identified metrics of importance to care partners included measures of sleep quality after ED discharge and psychological burden related to caregiving.42 Additional details on the studies are reported in Tables 1 and 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Included PICO-2 Care Transitions Outcome Studies

| Author Location Year | No. Patients (Mean Age) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Study Design | Intervention Type | Patient Reported Measures | Caregiver Measures | Utilization Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Foulon33 Belgium 2019 | 100 (NR) | Health care providers involved directly in MM during CT; patient needed to be recently discharged from a hospital and familiar with health CT. | Prior involvement in pilot projects on continuity of MM. | Qualitative study using moderated focus group interviews analyzed with a thematic analysis approach. Topic guides for HCPs and patients were related to problems in the continuity of MM. | N/A | Participants identified the main problems in MM during CT, clustered into themes as such: 1) problems at admission, 2) problems at discharge 3) problems as to professions, 4) problems as to patients/families, and 5) problems as to process | No specific caregiver measures or outcomes were identified. | Timely follow-up with PCP. |

| Gettel34 US 2020 | 26 (83.0) | Aged ≥65 y, presenting to ED within 7 d of a fall, and likely to be discharged to community based on clinician judgement. English/Spanish-speaking. | Altered mental status, un-domiciled individuals, residents of a NH, or those with no follow-up phone numbers. | Qualitative study using grounded theory methodology nested within larger feasibility trial (GAPcare study). Patient, caregivers, or joint patient-caregiver dyads participated in interviews. Interview guide queried domains of ED care, symptom management after ED discharge, quality of in-ED and outpatient provider communication, views of the CT, perceptions of barriers to follow-up, and perceptions of clinical trajectories. cognitive impairment identified by <4 on SIS. | N/A | PLWD themes/quotes: feelings of being overwhelmed and often choose to not obtain recommended follow-up. Some patients noted loss of independence, fear of falling. | Caregiver themes/quotes: safety at SNFs greater than at home costs of LTC, making modifications to their lives after a fall-related ED visit. (cognitive impairment specific). There was also communication/coordination of care between providers, caregiver health metrics (sleep, psychological burden). | NR |

| Schnitker35 Australia 2015 | 580 (80.3) | Patients age ≥70 y presenting to the ED at 1 of 8 study hospitals between 2011 and 2012. | In the ED ≥2 h before recruitment by research RN, too ill to provide consent, had participated in this study previously during another ED visit, did not have an interpreter available within 2 h, or those who were not able to participate in planned 7 and 28-d follow-ups. | Phase 1: study first involved a systematic review of the literature to identify important care gaps and process Qls for patients with cognitive impairment. These measures were presented to an advisory panel of research, clinical, and consumer stakeholders to develop draft process measures. Phase 2: multicenter prospective and retrospective cohort study. Draft measures were field tested with older adults ≥70 y recruited during an ED visit between Sam and 5pm to evaluate initial quality of care. Phase 3: PQIs were then modified based on field testing and re-voted by panelists in 2 rounds to develop final set of PQI items. | 22 QIs applied to older patients in the ED | A set of 11 PQIs for the evaluation of care processes relevant to older adult ED patients with cognitive impairment included: cognitive screening, delirium screening, delirium risk assessment, evaluation of acute change in mental status, delirium etiology, proxy notification, collateral history, involvement of a nominated support person, pain assessment, post-discharge follow-up, and ED LOS (proportion of older adults with ED stay >8 h). These were not necessarily patient-identified, but were formed by the group. | NR | Referrals for follow-up evaluation of cognitive status. |

CT, care transition; HCP, health care provider; LOS, length of stay; LTC, long-term care; MM, medication management; N/A, not applicable; NH, nursing home; NR, not reported; PCP, primary care provider; PLWD, person living with dementia; PQI, process quality indicators; QI, qualitative indicators; RN, registered nurse; SIS, 6-item screener; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Consensus Conference

GEAR 2.0-ADC members discussed and voted on topics to be prioritized in future research related to ED care transitions during a 2-day virtual Consensus Conference held on September 10–11, 2021. Through group discussion, participants identified a need for the development of clinical care pathways to improve the quality of ED-to-community care transitions and noted the potential benefits of a personalized approach to interventions for those with cognitive impairment. Participants also suggested the intensity of a care transition intervention (eg, community services, in-home support, telephone follow-up) should be tailored to the severity of cognitive impairment. All 61 (100%) members of GEAR 2.0-ADC voted, with stakeholder attendees obtaining agreement on primary research topics to accelerate ED care transitions research for patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners. The list of research areas, ordered by importance as determined by voting outcomes, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Priority Ranking of Key Research Questions*

| Research Priorities | Stakeholder Grouping |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Providers | Non-ED Providers | PLWD/Care Partners | All Stakeholders | |

|

| ||||

| What improves outcomes of ED-to-community care transitions among ED patients with impaired cognition and their care partners (eg, system, program operations, individual/care-partner strengths/needs) and how can these be personalized for vulnerable pops? | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| What matters most to ED patients with impaired cognition and their care partners during the ED-to-community transition and how can these priorities best be measured? | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| What barriers, facilitators, and strategies, specifically leveraging implementation science methods, influence engagement, uptake, and success of care transition interventions, including national guidelines, policies, and best practices? | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| How can care partners and community organizations be best engaged and empowered to improve ED-to-community care transitions? | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| How can communication quality surrounding ED-to-community transitions be optimally measured? | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

N = 61. ED providers n = 25. Non-ED providers n = 29. PLWD/care partners n = 7.

Discussion

This scoping review examines the literature on care transition interventions for patients with cognitive impairment receiving ED care and what measures of quality transitions are important for older adults with impaired cognition and their care partners. Our review had 3 primary findings. First, few successful care transition interventions exist, and there was substantial heterogeneity in components, setting, personnel, and outcomes assessed within the interventions. Second, patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners suggested several care transition outcomes aside from traditional healthcare utilization metrics. Third, GEAR 2.0-ADC Consensus Conference participants prioritized identifying what improves outcomes of ED-to-community care transitions among ED patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners and how efforts can be personalized for populations with additional barriers to care (eg, those living alone, rural populations). These findings will guide future research to improve ED-to-community care transitions for patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners.

This work is the first review to address ED-to-community care transitions for older adults with cognitive impairment and their care partners from a patient-centered perspective. This work expands upon prior reviews addressing ED-to-home,19 hospital-to-home,44 and nursing home-to-hospital45 care transitions for cognitively intact older adults. Available reviews including cognitively impaired older adults and their care partners have focused on qualitative studies addressing care transitions from home-to-institutional settings or more broadly across the health system.46,47 Our review also has important implications for clinical practice, policy, and research given the increasing prevalence of cognitive impairment among ED patients.6,7 Clinically, processes associated with ED-to-community care transitions are often associated with poor care coordination and ineffective communication, particularly for older adults with cognitive impairment.42,48 Attention in the clinical realm could be directed toward considering personalized approaches to care transition interventions, in that a ‘one size fits all’ approach would be unlikely to be successful with varying disease stages, access to resources, and care partner abilities.

Federal policy initiatives and reimbursement incentives could enhance the clinical uptake of ED-to-community care transition interventions. Currently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has prioritized post-hospitalization care transitions through the Community-based Care Transitions Program. CMS has established reimbursement for Transitional Care Management billing by outpatient clinicians, but post-ED care transitions are excluded.49,50 Going forward, CMS could create new billing codes for ED clinicians to bill for care transition service delivery. Furthermore, CMS reimbursement for telemedicine services during the COV1D-19 pandemic was rapidly implemented through regulatory flexibilities to provide older adults access to care in the setting most appropriate for them. Ensuring these reimbursement models remain are essential as telehealth could be a valuable tool for health care delivery in this population where discharge communication and coordination of subsequent visits may be difficult to navigate.51,52 Aside from payment considerations, we recognize that one large reason for the dearth of research in the ED-to-community care transitions space for patients with cognitive impairment is due to the historical exclusion of older adults with impaired cognition from research. NIH policies such as the “Inclusion Across The Lifespan” policy could encourage research and increase the existing knowledge base on this topic.53

As identified by the Consensus Conference participants, future research should focus on 2 priorities. First, we identify the need to focus research efforts on personalizing ED-to-community care transition interventions for certain at-risk populations. Second, researchers need to determine what matters most to patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners. Identifying ‘What Matters’ to older adults is a key pillar within the 4Ms framework established by the Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative in 2017.54,55 Wholesale paradigm shifts and innovative care transition interventions will need to be considered, developed, tested, and implemented in a population of persons living with dementia anticipated to reach 12.7 million people by 2050.56 We, thus, encourage researchers and other stakeholders to avoid constraining the development of care models and interventions to only those that are currently feasible within contemporary payment and policy structures. Funding entities, including the NIA, can be instrumental in ensuring that innovative care transition interventions can be tested and also in promoting the continued need for multidisciplinary networks similar to GEAR 2.0-ADC aiming to improve health care outcomes for patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners.

Our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. PICO-1’s focus on ED-to-community discharge likely neglected other key care transitions to and from the ED. By group consensus, the Care Transitions workgroup identified the chosen ED-to-community transition a priori as the most salient to address. From a search strategy perspective, we intentionally used ‘cognitive impairment’ rather than solely ‘dementia’. Although this may have introduced additional heterogeneity, we believe this more inclusive approach better captures the direct and indirect evidence that will guide ED provider practice and research priorities. Further, consistent with accepted scoping review methodologies,30 the quality of evidence identified was not explored in detail.

Conclusions and Implications

This systematic scoping review found few ED-to-community care transition interventions targeting cognitively impaired older adults and their care partners. Further, there was little data identifying care transition outcomes of importance to these groups. Personalizing care transitions for these ED patients and measuring what matters most during ED-to-community care transitions were identified as the highest priority areas for future ED research involving cognitively impaired older adults and their care partners. As such, research funding agencies, advocacy groups, and researchers should focus their resources and efforts on these domains, thereby developing the science to improve the health of this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication received support from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institute of Health under Award Numbers R21/R33AG058926, R61/R33 AG069822, K76AG074926 (JRF), R03AG073988 (CJG), K24AG054560 (MNS) and P30AG021342 (a Pepper Scholar award from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine; CJG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

JRF reports royalty income from Medbridge, Inc for continuing education courses related to hospital readmissions for older adults. CJG receives support for contracted work from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop hospital and health care outcome and efficiency quality measures.

Appendix.

Appendix 1.

The GEAR 2.0-ADC Network Authors

| Names | Degrees |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Aggarawal, Neelum | MD |

| Allore, Heather | PhD |

| Aloysi, Amy | MD, MPH |

| Belleville, Michael | HS |

| Bellolio, M Fernanda | MD |

| Betz, Marian (Emmy) | MD, MPH |

| Biese, Kevin | MD, MAT |

| Brandt, Cynthia | MD, MPH |

| Bruursema, Stacey | LMSW |

| Carnahan, Ryan | PharmD, MS, BCPP |

| Carpenter, Christopher | MD, MSC |

| Carr, David | MD |

| Chin-Hansen, Jennie | MS, RN, FAAN |

| Daven, Morgan | MA |

| Degesys, Nida | MD |

| Dresden, M Scott | MD, MS |

| Dussetschleger, Jeffrey | DDS, MPH |

| Ellenbogen, Michael | AA |

| Falvey, Jason | DPT, PhD |

| Foster, Beverley | HS |

| Gettel, Cameron | MD |

| Gifford, Angela | MA |

| Gilmore-Bykovskyi, Andrea | PhD, RN |

| Goldberg, Elizabeth | MD, ScM |

| Han, Jin | MD, MSc |

| Hardy, James | MD |

| Hastings, S. Nicole | MD |

| Hirshon, Jon Mark | MD, PhD, MPH |

| Hoang, Ly | BS |

| Hogan, Teresita | MD |

| Hung, William | MD, MPH |

| Hwang, Ula | MD, MPH |

| Isaacs, Eric | MD |

| Jaspal, Naveena | BA |

| Jobe, Deb | BS |

| Johnson, Jerry | MD |

| Kelly, Kathleen (Kathy) | MPA |

| Kennedy, Maura | MD |

| Kind, Amy | MD, PhD |

| Leggett, Jesseca | BS |

| Malone, Michael | MD |

| Moccia, Michelle | DNP |

| Moreno, Monica | BS |

| Morrow-Howell, Nancy | MSW, PhD |

| Nowroozpoor, Armin | MD |

| Ohuabunwa, Ugochi | MD |

| Oiyemhonian, Brenda | MD, MHSA, MPH |

| Perry, William | PhD |

| Prusaczk, Beth | PhD, MSW |

| Resendez, Jason | BA |

| Rising, Kristin | MD |

| Sano, Mary | PhD |

| Savage, Bob | HS |

| Shah, Manish | MD, MPH |

| Suyama, Joseph | MD, FACEP |

| Swartzberg, Jeremy | MD |

| Taylor, Zachary | BS |

| Tolia, Vaishal | MD, MPH |

| Vann, Allan | EdD |

| Webb, Teresa | RN |

| Weintraub, Sandra | PhD |

References

- 1.Albert M, McCaig LF, Ashman JJ. Emergency Department Visits by Persons Aged 65 and Over: United States, 2009–2010. NCHS data brief, no 130. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadogan MP, Phillips LR, Ziminski CE. A perfect storm: care transitions for vulnerable older adults discharged home from the emergency department without a hospital admission. Gerontologist 2016;56:326–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cetin-Sahin D, Ducharme F, McCusker J, et al. Experiences of an emergency department visit among older adults and their families: qualitative findings from a mixed-methods study. J Patient Exp 2020;7:346–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29: 49–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trends in Emergency Department Visits - HCUP Fast Stats. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent T, Lesser A, Israni J, Hwang U, Carpenter C, Ko KJ. 30-day emergency department revisit rates among older adults with documented dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:2254–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Messina FC, Miller DK, Callahan CM. Emergency department use among older adults with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2016;30:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucke JA, de Gelder J, Heringhaus C, et al. Impaired cognition is associated with adverse outcome in older patients in the emergency department; the acutely presenting older patients (APOP) study. Age Ageing 2018;47:679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Sullivan D, Brady N, Manning E, et al. Validation of the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test and the 4AT test for combined delirium and dementia screening in older Emergency Department attendees. Age Ageing 2018;47: 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Z, Coots LA, Kaganova Y, Wiener JM. Hospital and ED use among Medicare beneficiaries with dementia varies by setting and proximity to death. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter CR, Hammouda N, Linton EA, et al. delirium prevention, detection, and treatment in emergency medicine settings: a geriatric emergency care applied research (GEAR) network scoping review and consensus statement. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28:19–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bambach K, Southerland LT. Applying geriatric principles to transitions of care in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2021;39:429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens CE, Newcomer R, Blegen M, Miller B, Harrington C. The effects of cognitive impairment on nursing home residents’ emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:835–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Smith MD, Lex CK. The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaquis WP, Kaplan JA, Carpenter C, et al. Transitions of Care Task Force Report; 2012.

- 17.Hirschman KB, Hodgson NA. Evidence-based interventions for transitions in care for individuals living with dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58:S129–S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg MS, Carpenter CR, Bromley M, et al. Geriatric Emergency Department guidelines. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2014;63:e7–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gettel CJ, Voils CI, Bristol AA, et al. Care transitions and social needs: a Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research (GEAR) Network scoping review and consensus statement. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28:1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charles L, Jensen L, Torti JMI, Parmar J, Dobbs B, Tian PGJ. Improving transitions from acute care to home among complex older adults using the LACE Index and care coordination. BMJ Open Qual 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Spall HGC, Lee SF, Xie F, et al. Effect of patient-centered transitional care services on clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for heart failure: the PACT-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321:753–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes JM, Freiermuth CE, Shepherd-Banigan M, et al. Emergency department interventions for older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67: 1516–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dresden SM, Hwang U, Garrido MM, et al. Geriatric emergency department innovations: the impact of transitional care nurses on 30-day readmissions for older adults. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen LM, Kirkegaard H, Ostergaard LG, Bovbjerg K, Breinholt K, Maribo T. Comparison of self-reported and performance-based measures of functional ability in elderly patients in an emergency department: implications for selection of clinical outcome measures. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter CR, DesPain B, Keeling TN, Shah M, Rothenberger M. The Six-Item Screener and AD8 for the detection of cognitive impairment in geriatric emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpenter CR, Banerjee J, Keyes D, et al. Accuracy of dementia screening instruments in emergency medicine: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26:226–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo AX, Biese K, Carpenter CR. Defining quality and outcome in geriatric emergency care. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:107–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter CR, Mooijaart SP. Geriatric Screeners 2.0: time for a paradigm shift in emergency department vulnerability research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68: 1402–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brackett AL, Shah MN. Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network 2.0 – Advancing Dementia Care (GEAR 2.0 ADC) - Care Transitions Work Group. June 30 ed; 2021. Open Science Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gitlin LN, Maslow K, Khillan R. National research summit on care, services, and supports for persons with dementia and their caregivers. Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballabio C, Bergamaschini L, Mauri S, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of elderly people discharged from an emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 2008;3:245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosetti A, Gayot C, Preux PM, Tchalla A. Effectiveness of a geriatric emergency medicine unit for the management of neurocognitive disorders in older patients: results of the MUPACog Study. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord 2020;49: 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edmans J, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Gladman J, Conroy S. Specialist geriatric medical assessment for patients discharged from hospital acute assessment units: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;347:f5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen LH, Gregersen M, Barat I, Damsgaard EM. Early geriatric follow-up after discharge reduces mortality among patients living in their own home. A randomised controlled trial. Eur Geriatr Med 2017;8:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDonald Z, Eagles D, Stiell IG. LO77: compliance of older emergency department patients to community-based specialized geriatric services. CJEM 2017;19:S54–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Riordan Y, Bernard P, Maloney P, Enright A, McGrath C. Safer transitions: optimising care and function from hospital to home. Int J Integr Care 2017;17: A592. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah MN, Green RK, Jacobsohn GC, et al. Community paramedic-delivered care transistions intervention reduces emergency departmetn revisits among cognitively impaired patients. Poster presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; 2021. Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foulon V, Wuyts J, Desplenter F, et al. Problems in continuity of medication management upon transition between primary and secondary care: patients’ and professionals’ experiences. Acta Clin Belg 2019;74:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gettel CJ, Hayes K, Shield RR, Guthrie KM, Goldberg EM. Care Transition decisions after a fall-related emergency department visit: a qualitative study of patients’ and caregivers’ experiences. Academic Emergency Medicine 2020;27: 876–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnitker LM, Martin-Khan M, Burkett E, et al. Process quality indicators targeting cognitive impairment to support quality of care for older people with cognitive impairment in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22: 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liebzeit D, Rutkowski R, Arbaje AI, Fields B, Werner NE. A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:2950–2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray LM, Laditka SB. Care transitions by older adults from nursing homes to hospitals: implications for long-term care practice, geriatrics education, and research. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010;11:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afram B, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MH, Hamers JP. Needs of informal caregivers during transition from home towards institutional care in dementia: a systematic review ofqualitative studies. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saragosa M, Jeffs L, Okrainec K, Kuluski K. Using meta-ethnography to understand the care transition experience of people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia (London); 2021. 14713012211031779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashbourne J, Boscart V, Meyer S, Tong CE, Stolee P. Health care transitions for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Community-based Care Transitions Program: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Care Management: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovenheim S Telehealth: delivering care safely during COVID-19, Vol 2021; 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldberg EM, Jiménez FN, Chen K, et al. Telehealth was beneficial during COVID-19 for older Americans: a qualitative study with physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:3034–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hunold KM, Goldberg EM, Caterino JM, et al. Inclusion of older adults in emergency department clinical research: strategies to achieve a critical goal. Acad Emerg Med 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Age Friendly Health Systems: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2021;17: 327–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.