Abstract

Introduction: The South Pacific Medical Team (SPMT) has supported oral health care for Tongan juveniles since 1998. This voluntary activity, named the MaliMali (‘smile’ in Tongan) Programme, is evaluated in detail in this paper. Methods: This evaluation was guided by the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. The objectives were to explore: (i) whether the programme was accessible to Tongan schoolchildren (Reach); (ii) the impact of the programme on decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) scores and toothbrushing habits (Effectiveness); (iii) factors that affected the adoption of the programme (Adoption); (iv) whether implementation was consistent with the programme model (Implementation); and (v) the long-term sustainability of the programme (Maintenance). Results: The MaliMali Programme has grown into an international project, has spread countrywide as a uniform health promotion and is reaching children in need. Following implementation of this programme, the oral health of Tongan juveniles has improved, with a decrease in the mean DMFT index and an increase in toothbrushing. To provide training that will allow Tongans to assume responsibility for the MaliMali Programme in the future, dental health education literature was prepared and workshops on oral hygiene and the MaliMali Programme were held frequently. At present, the programme is predominantly managed by Tongan staff, rather than by Japanese staff. Conclusions: This evaluation found the MaliMali Programme to be feasible and acceptable to children and schools in the Kingdom of Tonga. The programme promotes oral health and provides accessible and improved oral health care in the school setting, consistent with the oral health-promoting school framework.

Key words: Prevention of dental caries, oral health-care system, fluoride, Kingdom of Tonga

Introduction

Tonga is a sovereign Polynesian state and archipelago composed of the Tongatapu Islands, which contain the capital city Nuku'alofa, the Ha'apai Islands, the Vava'u Islands, the Niua Islands, the ‘Eua Islands and more than 170 other islands. The population of Tonga is approximately 100,000, with juveniles (under 14 years of age) constituting 38% of the population1. Tonga's economy is non-monetary and heavily dependent on remittances from abroad. After 1970, the number of Tongans with dental disease (e.g. caries and periodontitis) increased2., 3., 4., and by 1998 many children had developed severe caries. Because toothbrushes and dentifrice were expensive and difficult to purchase at that time, both children and their parents neglected their oral hygiene. In addition, many Tongan people preferred to consume snacks and beverages that contained large amounts of sugar. It was observed that snacks and beverages were sold at primary schools and that students ate them at recess.

Research on Tongan dietary habits5 conducted in 2001 indicated that, among Tongan people, the intake frequency of modern Western food (e.g. breads with condiments) was 4.1 times greater than that of traditional primary food (e.g. yams, which are boiled with coconut cream and 0.2% salt-containing rainwater). In 19796, the preference rate for modern Western food was only 0.36 times higher than that for traditional primary food. Therefore, Tongan dietary habits changed rapidly over the 22-year period from 1979 to 2001. Moreover, sugar intake in 2001 was 19.3 times greater than that in 1979. A drastic change in dietary habits has led Tongans to use larger amount of condiments and to increase their sugar intake. These large changes in sugar consumption resulted in an increase in severe cases of caries in both juveniles and adults.

Dental health services in Tonga are provided by approximately 10 dentists (one dentist per 10,000 total population), 20 dental therapists and nurses, and several dental technicians. The role of dental therapists includes performing dental examinations, restoring teeth, administering local anaesthetic, extracting teeth, taking radiographs and performing preventative treatments; the role of dental nurses includes preparing and sterilising the dental instruments. These services were free until 2010, but the cost is now 5 pa'anga (2.5 USD) per treatment.

In 1998, there were many challenges to the practice of dentistry in Tonga (e.g. chronic shortage of manpower, inappropriate use of facilities and lack of materials) that prevented patients from receiving restorative care. Tooth extractions were frequently performed for pain relief. Following tooth extraction, many patients refused treatment with removable dentures because of the expense and potential discomfort. There is a need for oral-health promotion among Tongans. In addition, fluoridated toothpaste, mouthrinses and water are not widely available.

The South Pacific Medical Team (SPMT) was established in 1998 by Japanese dentists in private practice to improve dentistry in other countries via voluntary activities. In 17 years of voluntary activities, many dental hygienists, faculty and students at dental schools, medical doctors, nurses and dieticians have joined the SPMT to further promote oral health. One of the key tasks of the SPMT is to improve children's oral health in the Kingdom of Tonga (subsequently referred to here as Tonga); this programme is named MaliMali, or ‘smile’ in Tongan. In the MaliMali Programme, toothbrushing instruction (TBI), oral health education and periodic mouthrinsing with fluoride are performed as a school-based dental-health promotion. The effect of mouthrinsing with fluoride on the prevention of dental caries in Tonga has previously been reported7. Currently, the MaliMali Programme is co-managed by the SPMT, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Ministries of Health and Education in Tonga.

MaliMali Programme

Overview of the MaliMali Programme

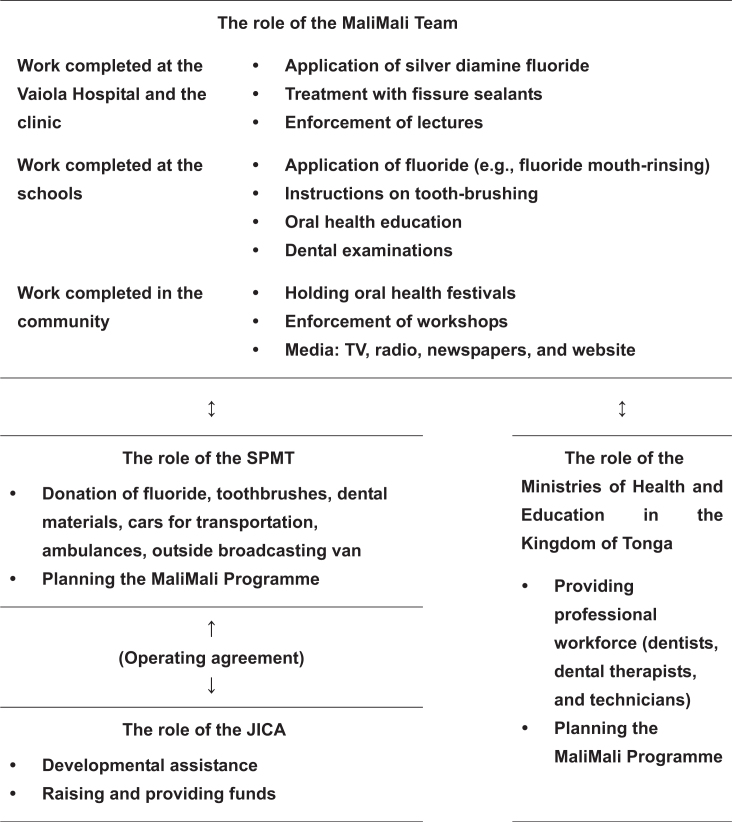

The SPMT, in partnership with JICA and the Ministries of Health and Education in Tonga, has managed the MaliMali Programme to improve the Tongan lifestyle through caries prevention and tooth preservation (Figure 1). These activities, including the ‘Oral Health Project in the Kingdom of Tonga’ (2006–2009), ‘The Project of Improving School-Based Oral Health Activity in the Kingdom of Tonga’ (2009–2012) and ‘The Project for Improving an Adult's Lifestyle Approach for Oral Health in the Kingdom of Tonga’ (2013–2016), have been supported by JICA.

Figure 1.

Structure of the MaliMali Programme

From 1998 to 2009, the following activities were carried out: (i) a programme for school-based dental health promotion at kindergartens and primary schools once a week; and (ii) educational workshops to promote dental health, which were held two or three times a year at schools, churches and assembly halls, for dental staff, schoolteachers, parents and children. Additionally, oral health festivals were held at markets, churches and health centres. Dental examinations and instruction on dental hygiene, toothbrushing and fluoride mouthrinsing were provided to participating Tongans. Between 2009 and 2012, literature on dental health education was provided in addition to those activities previously described. From 2013 to the time of writing of this article, adults have been included in the programme, and programmes for dental health promotion and the reduction and treatment of non-communicable disease have been implemented. Activities for people with disabilities, human resource development and the expansion of the MaliMali Programme have also been included.

School-based dental health promotion

The initial objective of the SPMT was technical and material support for dental treatment at the Vaiola Hospital, the main national hospital in Tonga, before extraction of permanent teeth in juvenile patients by dental therapists. Now the objective is the prevention of caries but not restorations and extractions. The SPMT implemented a school-based dental-health promotion programme that was managed by the MaliMali Team and contained SPMT members and dentists and dental therapists at Vaiola Hospital. Since 1998, the teams have visited kindergartens and primary schools to educate students about oral hygiene (e.g. by distributing leaflets and providing verbal instruction about snacks and beverages), toothbrushing with fluoride-containing dentifrice and fluoride mouthrinsing. They have also performed dental examinations. Additionally, the SPMT has provided fissure sealants for the permanent first molars of second-grade students at Vaiola Hospital. To provide feedback on promotional activities, the MaliMali Team frequently holds workshops with the staff of the Ministry of Education and teachers. The SPMT has donated supplies (e.g. fluoride, toothbrushes, toothpastes, dental materials, stationery and uniforms) to the MaliMali team.

The MaliMali Programme is conducted in almost all kindergartens and primary schools in Tonga and has dramatically decreased the prevalence of dental caries among Tongan juveniles. The objectives of this study, guided by the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework8., 9., 10., were to explore: (i) whether the programme was accessible to schoolchildren (Reach); (ii) the impact of the programme on decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) scores and toothbrushing habits (Effectiveness); (iii) factors that affected adoption of the programme (Adoption); (iv) whether implementation was consistent with the programme model (Implementation); and (v) the long-term sustainability of the programme (Maintenance).

Methods

The activities of the MaliMali Programme were approved by the National Health Ethics and Research Committee (NHERC), Ministry of Health, Nuku'alofa, Tonga (MH: 53.02). After ethical approval, all participants were initially selected to take part in the MaliMali Programme, and written letters of consent were obtained from all participants and from the parents/guardians of participants who were under 18 years of age. The written consent procedure was approved by the NHERC. Our research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Evaluation framework

The evaluation was guided by the RE-AIM framework8., 9., 10.. This framework is designed to assess complex health-promotion interventions in ‘real world’ settings and to examine the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of a programme8. The RE-AIM dimensions and their relationship to the research questions and data sources are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study application of the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) dimensions8., 9., 10.

| Dimension | Key indicators |

|---|---|

| Reach | Per cent of the target population (schoolchildren) |

| Effectiveness | Decrease in mean DMFT scores |

| Improvement in toothbrushing habits | |

| Adoption | Per cent of schools participating in programme |

| Characteristics of collaborators | |

| Implementation | Consistency of programme delivery |

| Costs | |

| Maintenance | Continuation, independency, expansion of programme |

DMFT, decayed, missing and filled teeth.

Analysis

Research on the diffusion of the MaliMali Programme

The number of schoolchildren participating in the MaliMali Programme was assessed in each facility every August.

Research on the prevalence of dental caries

The prevalence of dental caries in Tonga was determined in 2001 and 2011 (Table 2). The study population was 12-year-old children, and the data were obtained from 51 boys and 25 girls in 2001 and from 133 boys and 90 girls in 2011. In 2001 the subjects had participated in the MaliMali Programme for 1 year or less and in 2011 the subjects had participated in the MaliMali Programme for at least 7 years. Caries were detected by inspection according to the manual published by the Japanese Society of School Health11 with reference to reports by Kobayashi et al. and Nakamura et al.12., 13., 14.. Two experienced dentists performed caries examination using a mirror and probe under artificial light, facing subjects sitting in a chair. The examination results were recorded for each tooth. A dental explorer was used to remove dental plaque and to assess the presence of dental caries.

Table 2.

Prevalence of caries in 12-year-old children in the Kingdom of Tonga, 2001 and 2011

| Variable | Sex | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2011 | ||

| Mean DMFT | Boys | 4.40 | 2.08 |

| Girls | 5.81 | 2.38 | |

| Total | 4.86 | 2.20 | |

| DMF person rate (%) | Boys | 89 | 65 |

| Girls | 91 | 73 | |

| Total | 90 | 68 | |

51 boys and 25 girls participated in 2001; 133 boys and 90 girls participated in 2011.DMF, decayed, missing and filled; DMFT, decayed, missing and filled teeth.

Investigation of toothbrushing habits

In 2008, the toothbrushing habits of 829 children in all classes of six primary schools on Tongatapu Island were examined via a survey that was read aloud and completed by MaliMali staff and classroom teachers. The target population was children 5–14 years of age who had participated in the MaliMali Programme for 1–9 years. The response rate was 100%.

Results

Reach

Reach of individual health services

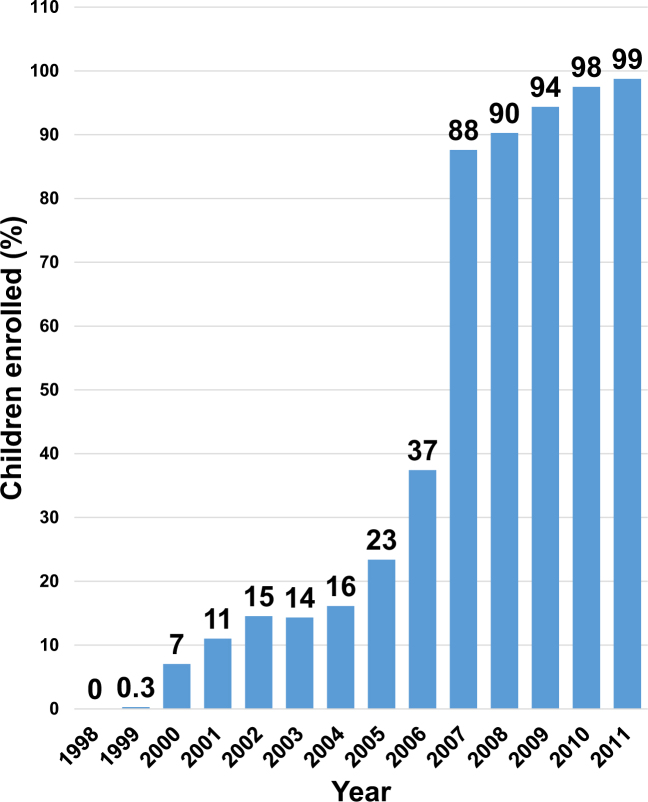

Figure 2 shows the increase in the number of schoolchildren enrolled in the MaliMali Programme each year. The initial MaliMali Programme enrolled 0.3% of Tongan children in 1999, and the percentage of enrolled children rose to 88% in 2007 and to 99% in 2011.

Figure 2.

Percentage of children enrolled in the MaliMali Programme, according to year, in the Kingdom of Tonga.

Effectiveness

Decrease in the mean DMFT scores

As shown in Table 2, the mean DMFT scores for boys, girls and all children in 2001 were 4.40, 5.81 and 4.86, respectively, and the DMF person rates for boys, girls and all children were 89, 91 and 90, respectively. In 2011, the mean DMFT scores for boys, girls and all children were 2.08, 2.38 and 2.20, respectively, and the DMF person rates for boys, girls and all children were 65, 73 and 68, respectively. The mean DMFT score and the DMF person rate among both boys and girls showed significant decreases in 2011 compared with the 2001 values.

Improvement in toothbrushing habits

In 2008, all children reported brushing their teeth at least once per day. Of these children, 17.5% reported habitually brushing their teeth once a day, 45.6% reported brushing their teeth twice a day and 36.9% reported brushing their teeth at least three times a day (data not shown).

Adoption

Per cent of schools participating in the programme

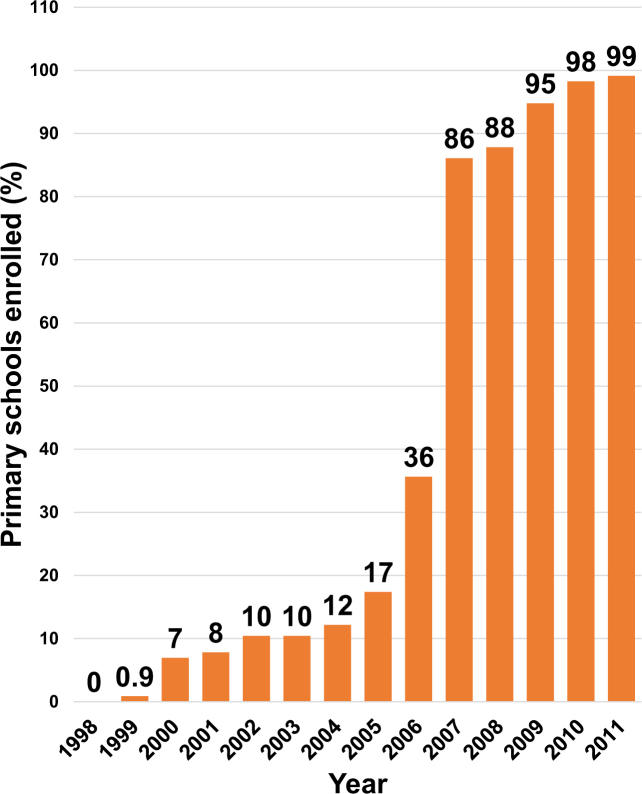

Figure 3 illustrates the increase in the number of primary schools participating in the MaliMali Programme each year. The MaliMali Programme began with enrolment of 0.9% of Tongan primary schools in 1999. The proportion of participating primary schools rose to 86% in 2007 and to 99% in 2011.

Figure 3.

Percentage of primary schools enrolled in the MaliMali Programme, according to year, in the Kingdom of Tonga.

Establishment of international cooperation

The operating agreement between the SPMT and JICA signed in 2006 formalized the relationship between the Ministries of Health and Education in Tonga, and the SPMT and JICA, to establish the MaliMali Programme as an international project involving primary schools.

Implementation

Was the programme implemented as planned?

The MaliMali Programme proceeded as follows: the MaliMali team visited kindergartens and primary schools once a week, guided children in toothbrushing with help from teachers and provided the fluoride-containing mouthrinses. The MaliMali team also gave presentations on oral health twice a year, which included provision of leaflets and other media to schools. When the MaliMali team did not visit, the children brushed their teeth after lunch under the supervision of their teachers.

What is the cost of implementing the programme?

The SPMT donated fluoride, toothbrushes, dental materials, cars for transportation and other necessities with its own funds. In 2006, the SPMT entered into a contract with the JICA, with a portion of the costs of executing the MaliMali Programme covered by funds from this contract. The costs of fluoride powder and of the fluoride products (MIRANOL® and ORA-BLISS®) were 0.18 and 0.9–1.8 USD per person per year, respectively, in Japan. The solution has no cost because rainwater is used in Tonga. The tanks and the bottles required to store and deliver the fluoride solution cost 36 and 9 USD, respectively, and these can be used semipermanently. Additionally, because all children in Tonga have toothbrushes, the cost of toothbrushes is negligible (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost of implementing the MaliMali Programme

| Materials | Cost (USD) |

|---|---|

| MIRANOL® | 0.18 |

| ORA-BLISS® | 0.9–1.8 |

| Solution | 0 |

| Tank | 36 |

| Bottle | 9 |

| Toothbrush | 0 |

USD, US dollars.

Maintenance

What factors affect the long-term maintenance of the programme?

The MaliMali Programme was first implemented in 1998 and has been ongoing since then. The programme has become countrywide and uniform under independent management by Tongans. This has resulted from the following factors.

-

•

The operating agreement between the SPMT and JICA promoted an effective relationship between the SPMT and the Ministries of Health and Education in Tonga

-

•

Dental, medical and education staff shared information via workshops

-

•

Literature for dental health education. Because education regarding dental hygiene was needed for students, faculty (e.g. teachers and principals) and dental staff in Tonga, educational literature, entitled ‘The Textbook of Dental Health’15, was drafted by Tongan dental staff and the SPMT. This educational literature contains three individual books that describe three topics: (i) for dental staff, basic prevention and therapy in dentistry; (ii) for faculty, mainly prevention and therapy in dentistry (Table 4); and (iii) for students, the benefits of improvements in dental hygiene, illustrated with figures and photographs.

-

•

Publicity. The MaliMali Programme was advertised via Tongan television, radio, newspapers and the website of the government of Tonga16. Dentists on the MaliMali Team periodically presented educational lectures about dental health, including the outcomes of the MaliMali Programme, on Radio Tonga. An ‘Oral Health Festival’ was also held at city sites (e.g. markets and churches) to introduce the SPMT promotion to citizens.

Table 4.

Table of contents of the textbook for faculty

| I. | The MaliMali Programme | 1 |

| 1. Enforcement method of the MaliMali Programme | ||

| 2. Achievements after the MaliMali Programme | ||

| 3. A guiding principle and aim in 2010 | ||

| II. | Oral health and disease | 4 |

| III. | Dental plaque | 5 |

| IV. | Dental caries | 6 |

| V. | Gingivitis | 8 |

| VI. | Periodontitis | 9 |

| VII. | Sugar control | 10 |

| VIII. | Tooth-brushing | 11 |

| IX. | Fluoride | 14 |

| 1. Fluoride mouth-rinsing | ||

| 2. Professional fluoride application | ||

| 3. Fluoride toothpaste | ||

| X. | Preventive treatment | 18 |

| 1. Fissure sealant | ||

| 2. SAFORIDE: [Ag(NH3)2]F | ||

| XI. | Level of health care | 22 |

| 1. Community care | ||

| 2. Self-care | ||

| 3. Home care | ||

| 4. Professional care |

Discussion

This evaluation adds considerably to our understanding of the school-based oral-health promotion programme for children, the ‘MaliMali Programme’, with good evidence that the programme is reaching the majority of students, is having positive effects on student health and well-being, has been adopted successfully in schools, is being implemented as intended and can be maintained with sustained resourcing.

A number of key themes emerging from the RE-AIM analysis are discussed here to evaluate the progress of the MaliMali Programme in 1998–2011.

Key points of the MaliMali Programme

Diffusion of the MaliMali Programme

Although many faculty members from the primary schools were interested in the MaliMali Programme before 2006, it was difficult for them to become involved in the programme because they were affiliated with the Ministry of Education but not with the Health Ministry. Following the formation of an agreement between the SPMT and JICA and the Tonga Ministries of Health and Education in 2006, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, many more primary schools joined the promotion. Additionally, the second program in 2009 expanded efforts to kindergartens, and the MaliMali Programme became a countrywide program.

Collaboration with JICA

The aim of JICA was not to finance the activities but to establish and carry out the project through collaboration. Because the project was planned using the Project Cycle Management Method (PCM), the first applicants of the JICA project studied the PCM via the JICA seminar. In the PCM, it is most important to create the final goal, followed by the reach and methodology (equipment, materials, talents and costs) needed to achieve the desired outcome.

For execution of the MaliMali Programme, fluoride and cars are important resources. Because fluoride must be transported by sea with permission from the Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan, document preparation is often time consuming. Additionally, the cars needed to deliver the fluoride and other materials to schools in Tonga must be obtained using programme funds because the purchase of such items is not within the JICA budget.

To train Tongans who will assume responsibility for the MaliMali Programme in the future, the SPMT provided financial support for a Tongan dentist to learn oral surgery in Japan for 8 years beginning in 2001. She obtained a PhD in oral pathology from Nihon University and learned about oral hygiene in Japan. Currently, she is working as one of the organisers of the MaliMali Team and as a specialist in oral pathology in Tonga.

Collaboration with the Ministries of Health and Education

To request the permission of the Ministry of Health to implement the MaliMali Programme, the first SPMT and Tongan dental staff carried out the small-scale programme at one primary school and three kindergartens (total of 44 students), and presented an overview of the programme and its results. Additionally, to collaborate with the Ministry of Education, workshops about oral hygiene and the MaliMali Programme were often held for the school administrators and teachers. In addition, the JICA collaboration was helpful in working jointly with the SPMT and the Ministries of Health and Education.

A class for oral health promotion has now begun for fourth-grade students at all schools in Tonga using the aforementioned educational literature.

Reduction in the prevalence of dental caries

Because fluoride mouthrinsing is a well-known, highly efficacious and low-cost method for the prevention of caries17., 18., it is appropriate for school-based oral-health promotion in a developing country such as Tonga. Moreover, because the caries-prevention effect of fluoride-containing dentifrice was established in 1945 and more than 100 reports have since provided evidence of its efficacy19., 20., the MaliMali Programme also included TBI with a fluoride-containing dentifrice. Previously5, Tongans did not have any established toothbrushing practices; however, all children surveyed reported brushing their teeth more than once a day in 20087. This result is probably associated with reductions in both mean DMFT scores and the DMF personal rates in both genders (Table 2). The critical point for starting fluoride mouthrinsing to prevent caries in the first molars is at 4–5 years of age13; however, the ages of first-grade Tongan students range from 5 to 7 years of age as a result of the educational policy, as well as the economic status of parents. Thus, school-based fluoride mouthrinsing was expanded to kindergartens. Furthermore, the MaliMali Programme has provided fluoride application for deciduous teeth and silver fluoride treatment for early-stage caries since 2009.

Cost-effectiveness of the MaliMali Programme

Because the MaliMali Programme is applied in a group setting, there is little individual cost.

As discussed in the Implementation of the Results, the cost of the MaliMali Programme, including the purchase of fluoride, the materials for fluoride mouthrinsing and toothbrushes, is lower than for treatment of caries.

Geographical constraints

The MaliMali Programme is now managed by Tongan staff throughout Tonga via the following method. First, the MaliMali Programme was performed at only one kindergarten as the model. Second, the results of the programme were shown to the Tonga Ministries of Health and Education and the JICA. Therefore , the MaliMali Programme became a cooperative project between SPMT, JICA and the Ministries of Health and Education in Tonga, and schoolteachers also recommended the programme. As a result, this programme was successful.

One of the major drawbacks of the MaliMali Programme was visiting the schools and delivering the fluoride for the school-based programme. To resolve this issue, the SPMT donated used cars to the dental office in Viola Hospital. In addition, the programme is now carried out in health centres in various regions as a sub-base other than schools.

General management

As shown in Figure 1, the planning of the MaliMali Programme, the donation of the equipment and the materials, and funding were the responsibility of the SPMT and JICA. Provision of the professional workforce and allocation of budget for the dental office in Viola Hospital and the primary schools were performed by the Tonga Ministries of Health and Education. Performance of the MaliMali Programme, the management of the equipment and the materials and the preparation of fluoride according to its data sheet were carried out by Tongan dental staff.

For training Tongan staff, three types of dental health-education literature were prepared, and workshops on oral hygiene and the MaliMali Programme were commonly held. Thus, at present, the programme is predominantly managed by Tongan staff rather than by Japanese staff.

Issues with the MaliMali Programme and potential solutions

This SPMT-provided school-based dental-health promotion is not without issues. One is the low number of school days in Tonga, usually approximately 175 days (35 weeks), although this has recently increased to 200 days (40 weeks) in some primary schools; this number is low relative to the number of school days in Japan21. In addition, Tongan schools are closed on rainy days, and these irregular weather-related holidays reduce opportunities for students to receive fluoride mouthrinsing at school. For example, there was a case in which students were not able to receive fluoride mouthrinsing in school because their teacher, who kept their toothbrushes, took the day off and the students were unable to retrieve their toothbrushes. Additionally, other teachers found that students left toothbrushes behind and decided to exclude them from rinsing as a disciplinary measure. To solve these issues, the SPMT has suggested the following: (i) revisiting schools that have irregular holidays to carry out fluoride mouthrinsing again; and (ii) separating fluoride mouthrinsing from TBI. The SPMT has donated toothbrushes, fluoride-containing dentifrice, fluorides, dental materials, instruments and vehicles. All of these activities have contributed to providing and maintaining juvenile oral health in Tonga.

Future directions

The SPMT is planning to install salt fluoridation22 in Tonga. Because Tongan people use rainwater for cooking and drinking, water fluoridation is not an appropriate method for caries control, despite its established benefits23., 24.. Since the implementation of a dental-hygiene class for fourth-grade students was started in 2013, Tongan children may understand the importance of oral health as they age.

The Ministry of Health has expressed that the prevention, reduction and treatment of non-communicable disease is a current health issue. To resolve this concern, the SPMT has already started a new promotion to improve adult health via tooth preservation (e.g. prevention and treatment of caries and of periodontitis) as well as the modification of adult lifestyles. This new promotion will continue to support the juveniles currently enrolled in the programme. Expanding the promotion to adults means that the MaliMali Programme will be able to care for all generations of Tongan people in the near future.

Conclusion

This evaluation of the MaliMali Programme is feasible and acceptable to children and schools in the Kingdom of Tonga. The programme provides oral health promotion and accessible, improved oral health-care in the school setting, consistent with the oral health-promoting school framework.

Acknowledgements

These activities were supported by the JICA (2006–2009, 2009–2012 and 2013–2016), as described in the main article. The authors wish to thank all members of the MaliMali Team, the staff of Viola Hospital, the Ministries of Health and Education in the Kingdom of Tonga and the entire nation of Tonga.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authorship statement

Reiri Takeuchi, Kohji Kawamura, Sayuri Kawamura and Seigo Kobayashi designed the study; Reiri Takeuchi, Kohji Kawamura, Sayuri Kawamura, Mami Endoh, Chizuru Uchida, Sisilia Fifita, Amanaki Fakakovikaetau and Seigo Kobayashi performed the research; Reiri Takeuchi, Kohji Kawamura, Sayuri Kawamura, Chizuru Uchida, Chieko Taguchi, Takato Nomoto, Koichi Hiratsuka and Seigo Kobayashi analysed the data; Reiri Takeuchi, Kohji Kawamura, Sayuri Kawamura and Seigo Kobayashi drafted the paper.

References

- 1.Western pacific country health information profiles: 2011 revision. World Health Organization Western Pacific Region 2011.

- 2.Cutress TW, Powell RN, Kilisimasi S, et al. A 3-year community-based periodontal disease prevention programme for adults in a developing nation. Int Dent J. 1991;41:323–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutress TW, Powell RN, Ball ME. Differing profiles of periodontal disease in two similar South Pacific island populations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1982;10:193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1982.tb00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell RN, Cutress TW. Changing patterns of caries prevalence in Tongatapu. Odontostomatol Trop. 1981;4:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi R, Kawamura K, Kawamura S, et al. Program to improve the oral health of school children in the Kingdom of Tonga: the MaliMali program. Int J Oral-Med Sci. 2012;11:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adachi M, Yamamoto T. Health and food habit – studies of food habit changes among the people of Tonga. Nihon Shika Ishikai Zasshi. 1982;35:31–38. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi R, Kawamura K, Kawamura S, et al. Effect of school-based fluoride mouth-rinsing on dental caries incidence among schoolchildren in the Kingdom of Tonga. J Oral Sci. 2012;54:343–347. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.54.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, et al. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:688–694. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banfield M, McGorm K, Sargent G. Health promotion in schools: a multi-method evaluation of an Australian School Youth Health Nurse Program. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology . Revised ed. Japanese Society of School Health; Japan: 2008. The Manual of Medical Examination for School Children. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi S, Yano M, Hirakawa T, et al. The status of fluoride mouthrinse programmes in Japan: a national survey. Int Dent J. 1994;44:641–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S, Kishi H, Yoshihara A, et al. Treatment and posttreatment effects of fluoride mouthrinsing after 17 years. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura A, Sakuma S, Yoshihara A, et al. Long-term follow-up of the effects of a school-based caries preventive programme involving fluoride mouth rinse and targeted fissure sealant: evaluation at 20 years old. Int Dent J. 2009;59:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Textbook of Dental Health . SPMT; Saitama, Japan: 2011. Dental Office, Vaiola Hospital, Ministry of Health, Tonga, South Pacific Medical Team and Japan International Cooperation Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malimali program continues to improve school-based oral health in Tonga. Government of Tonga Web site. Available from: http://www.mic.gov.to/aid-programs/aid-japan/2856. Accessed 27 September 2016.

- 17.Twetman S, Petersson L, Axelsson S, et al. Caries-preventive effect of sodium fluoride mouthrinses: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:223–230. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sköld UM, Petersson LG, Birkhed D, et al. Cost-analysis of school-based fluoride varnish and fluoride rinsing programs. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66:286–292. doi: 10.1080/00016350802293978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan MV, Crowley SJ, Wright C. Economic evaluation of a pit and fissure dental sealant and fluoride mouthrinsing program in two nonfluoridated regions of Victoria, Australia. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray JJ. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1986. Appropriate Use of Fluorides for Human Health. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan Web site. Available from: http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo3/004/siryo/04120701/005/001.htm. Accessed 28 December 2013. Japanese.

- 22.Promoting Estupiñán-Day S, Health Oral . Pan American Health Organization; Washington, DC, USA: 2005. The Use of Salt Fluoridation to Prevent Dental Caries. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burt BA, Eklund SA. In: Dentistry, Dental Practice, and the Community. 6th ed. Rudolph P, editor. Elsevier Inc; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2005. Fluoridation of drinking water; pp. 326–346. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hargreaves JA. Water fluoridation and fluoride supplementation: considerations for the future. J Dent Res. 1990;69:505–836. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690S148. Spec No: 765–770; discussion 820–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]