Abstract

Objective: To investigate the effect of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) and potassium iodide (KI) treatment on dentine discolouration and the shear bond strength (SBS) of glass ionomer cements (GICs) to artificial caries-affected dentine. Materials and methods: Dentine slices from human molars were demineralised to mimic caries-affected dentine. They were randomly allocated for treatment (n = 20 per treatment) with SDF + KI, SDF (positive control) or water (negative control). All slices were immersed in the artificial saliva for 24 hours after treatments. The colour of the treated surfaces was assessed using the CIELAB system. Lightness values were measured. Total colour change (∆E) was calculated using water as the reference group, and was visible to the naked eyes if ∆E > 3.7. All dentine slices were bonded with GICs. The SBS was assessed using a universal testing machine. Colour parameters and the SBS were analysed using a one-way ANOVA test. Results: The slices treated with SDF + KI had a higher lightness value those slices treated with water, whereas those treated with SDF presented a lower lightness value compared with those treated with water. The treatment with SDF + KI did not introduce any adverse colour effect to demineralised dentine (∆E = 14.4), whereas the application of SDF alone caused significant staining (∆E = 24.6). The SBS values (mean ± SD) after treatment with SDF + KI, SDF and water were 3.0 ± 1.4 MPa, 2.3 ± 0.9 MPa and 2.6 ± 1.1 MPa, respectively (P = 0.217). Conclusion: The immediate application of KI solution after SDF treatment does not negatively affect adhesion of GICs to artificial caries-affected dentine. Moreover, KI treatment can reduce discolouration of demineralised dentine caused by SDF.

Key words: Silver diamine fluoride, potassium iodide, shear bond strength, discolouration, glass ionomer

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries, defined as a localised, pathological process with multiple factors, softening dental hard tissues and proceeding to the formation of cavities, continues to be a prevalent disease all over the world1. In recent years, the development of restorative materials and advancement in our conception of the caries process have created the capability to practice in consideration of a minimally invasive dentistry philosophy2. It requires performing management with as little tissue loss as possible and without causing any destruction to the adjacent healthy tooth tissues3. Carious dentine lesions were characteristically defined as comprising two different layers: an outer layer of bacterially infected dentine (caries-infected dentine); and an inner layer of caries-affected dentine4. The outer layer has been regarded as being highly demineralised and exhibiting irreversible denatured collagen fibrils with an obvious disappearance of cross-linkages, whereas the inner layer is not affected with bacteria and is partially demineralised and physiologically remineralisable5. Thus, caries-affected dentine should be preserved in clinical treatment based on the philosophy of minimally invasive dentistry. Consequently, caries-affected dentine other than normal dentine has commonly been the bonding substrate in clinical settings.

Silver diamine fluoride [Ag(NH3)2F] (SDF) is a topical fluoride solution that has been used to halt dental caries in a concentration of 38% (44,800 ppm fluoride) throughout the world since the early 1970s6. SDF currently has approval from the Food and Drug Administration in the USA as a Class-II medical device for the management of tooth hypersensitivity. It has also been used as an anti-cariogenic agent to reduce the growth of cariogenic biofilms7. In addition, SDF positively influences dentine remineralisation8, inhibits dentine demineralisation and prevents dentine collagen from degradation9. Moreover, it can promote the transformation of hydroxyapatite into fluorapatite with reduced solubility10, which increases resistance of dental hard tissues to acidic challenge. The resistance of proteins to collagenase attacks also increases due to the reaction between SDF and dentine organic matrix9., 11.. A randomised, controlled trial concluded that 38% SDF had a better result than the interim restorative treatment using glass ionomer cements (GICs) to arrest cavitated caries in primary teeth12. A systematic review confirmed that 38% SDF was effective in arresting dentine caries in deciduous teeth among children13. Additionally, caries removal is not needed before application of SDF, which can simplify treatment procedures. Nevertheless, SDF has a major adverse effect that stains the caries lesion black because of the reaction of SDF products with tooth tissues6. SDF has not been widely accepted by patients with aesthetic concerns due to its inherent disadvantage. Two alternatives have been suggested to minimise this side-effect. One is to use a saturated potassium iodide (KI) solution, which can react with residual silver ions, to eliminate the staining effect14. However, the colour-eliminating effect is still not well understood when SDF and KI are applied to caries-affected dentine. The other alternative is to apply GICs or composites over SDF to mask the stained carious lesion and as a direct restoration after application of SDF15.

Recently published studies16., 17. reported that SDF arrested caries lesions with no further progression after 2–3 years when it was applied to cavitated caries with no excavation. It is noteworthy that cavities were left open without filling in these studies after application of SDF. Restorations are generally needed for cavitated lesions to allow for an easily cleanable surface that may reduce the potential for secondary caries initiation. Although laboratory studies14., 18. report that application of SDF is compatible with restorations with GICs, to the authors’ knowledge there is insufficient evidence concerning the adhesion properties of GIC restorations when they are bonded to caries-affected dentine surfaces previously treated with SDF and KI. Therefore, the aim of this in vitro study was to investigate the effect of SDF and KI treatment on tooth discolouration and the shear bond strength (SBS) of GICs to artificial caries-affected dentine. Two null hypotheses were tested: SDF + KI treatment does not introduce staining effect on artificial caries-affected dentine; and SDF + KI treatment does not affect adhesion of GICs to artificial caries-affected dentine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

Sixty non-carious human third molars were collected with the patients’ written consent according to regulations at the University of Hong Kong. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (IRB UW 18-404). This research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The teeth were stored in a 0.1% thymol solution at 4 °C prior to section. The study design is shown in Figure 1. Sixty dentine slices with 2-mm thickness were prepared from 60 sound third molars using a low-speed saw with a diamond blade (ISOMET 1000; Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). All dentine slices were embedded using a dental cold-cured acrylic (ProBase Cold, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Liechtenstein). The surfaces of the dentine slices were polished with micro-fine 2000-grit sanding paper under running water. All samples were immersed in a demineralising solution (pH 4.4, 50 mm acetate, 2.2 mm KH2PO4, 2.2 mm CaCl2) for 7 days at 25 °C9. They were then allocated to three groups (n = 20 per group). For group SDF + KI, the demineralised surfaces were treated with SDF + KI (Riva Star, SDI, Bayswater, Australia). A 38% SDF solution from silver capsules was topically applied to the demineralised surfaces, with immediately applying a saturated KI solution from green capsules to treatment site until creamy white turned clear. Treated surfaces were adequately washed with distilled water19. For group SDF, the positive control group, the demineralised surfaces were treated with a 38% SDF solution (Saforide; Toyo Seiyaku Kasei, Osaka, Japan). For group water, the negative control group, the demineralised surfaces received application of water. After 30 minutes, all samples were immersed in the artificial saliva at 25 °C for 24 hours.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. GIC, glass ionomer cement; KI, potassium iodide; SBS, shear bond strength; SDF, silver diamine fluoride.

Colour assessment

Colour assessments (n = 20 per group) of dentine samples were performed after 1-day immersion in the artificial saliva. The colour of the treated dentine surface was assessed using a colorimeter (NR10QC, General Colorimeter; 3nh, Shenzhen, China). The CIE system (Commission International del’Eclairage) was used to three-dimensionally elucidate the colour by recording the L* a* b* colour coordinates. The L* axis represented lightness ranging from black (0) to white (100), the a* axis represented red (+a*) to green (−a*), and the b* axis described yellow (+b*) to blue (−b*). The measurements of L*, a* and b* were triplicate. The mathematical equation ∆E = [(∆L)2 + (∆a)2 + (∆b)2]1/2 was employed to calculate the colour difference between the experimental groups and the negative control group20. The discolouration of each tooth was clinically perceptible to naked eyes if ∆E was more than 3.7 units (perceptibility threshold)21.

Shear bond strength test and failure mode analysis

After colour assessment, all dentine samples (n = 20 per group) were bonded with GICs (Ketac-Molar; 3M/ESPE Dental Products, St Paul, MN, USA). A Teflon mould with 4-mm height and 3-mm diameter was placed on the demineralised dentine surfaces22. GICs in capsules were mixed using a rotational/centrifugal capsule mixing unit (RotoMix, 3M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA) for 10 seconds, and then the mixture was applied in the Teflon mould to form a cylindrical button. All GICs were chemically cured. After bonding, samples were stored in 100% humidity at 37 °C for 24 hours after removal from the mould to allow complete setting of GICs. The SBS test was performed with a universal testing machine that had a flat-edge loading head (ElectroPuls 3000; Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). A shear force was applied perpendicularly to the GIC cylindrical button at a distance of 1 mm from the dentine surface to the loading head. The loading head moved at a fixed rate of 1 mm/minute. The load necessary to debond GICs was recorded in Newtons. The bond strength was expressed in mega-Pascals (MPa) by dividing the load at failure by the bonded surface area in square mm.

The debonded samples were examined under an optical microscope at 20 × magnification. The failure modes were categorized as three types: Type 1, adhesive failure between dentine and GICs with exposing dentine surfaces; Type 2, cohesive failure in GICs or in dentine; and Type 3, partially adhesive failure and partially cohesive failure (mixed failure)23. Some of the fractured samples were sputter-coated with gold and viewed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Hitachi S-4800 FEG Scanning Electron Microscope; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) to obtain images with higher magnification.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed with IBM SPSS Version 25.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All data were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test (P > 0.05). Colour parameters and the SBS were analysed using a one-way ANOVA with post hoc test. The distribution of failure modes for the three groups were analysed by a chi-square and Fisher’s exact test. A P-value lower than 5% was considered as statistically significant for all tests.

RESULTS

Colour assessment

The colour characteristics for each dentine sample were examined to investigate whether the treatments introduced any discolouration effect compared with the colour of the negative control dentine (Table 1). The total colour change (∆E) and values of L* a* b*, and of the three groups are shown in Table 1. Data confirmed that group SDF + KI had significantly higher L* values than that of the negative control group, whereas group SDF presented significantly lower lightness compared with the negative control group. The colour differences (∆E) between the treated and the non-treated dentine samples were calculated based on the colour difference formula using the mean values of L*, a* and b*. Both of the ∆E values for group SDF + KI and group SDF were more than 3.7 units. The treatment with SDF + KI did not introduce any adverse colour effect to dentine surfaces, whereas the application of SDF alone caused significant staining.

Table 1.

Comparison of the colour parameters between natural dentine (negative control) and dentine after treatments (n = 20)

| Group | L* | a* | b* | ∆E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 55.6 ± 4.3 | 4.6 ± 2.3 | 9.6 ± 6.0 | N/A |

| SDF + KI | 69.8 ± 7.1† | 2.1 ± 0.6† | 10.5 ± 4.8 | 14.4 |

| SDF | 32.1 ± 4.5† | 8.6 ± 1.5† | 3.6 ± 2.5* | 24.6 |

L*, a* and b* refer to the colour coordinates. The L* axis represented lightness ranging from black (0) to white (100), the a* axis represented red (+a*) to green (-a*) and the b* axis described yellow (+b*) to blue (-b*). ∆E is the calculated colour difference between treated and control dentine. Data are means ± standard deviation.

KI, potassium iodide; SDF, silver diamine fluoride.

Indicates significant difference from control dentine within each colour coordinate (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Shear bond strength test and failure mode analysis

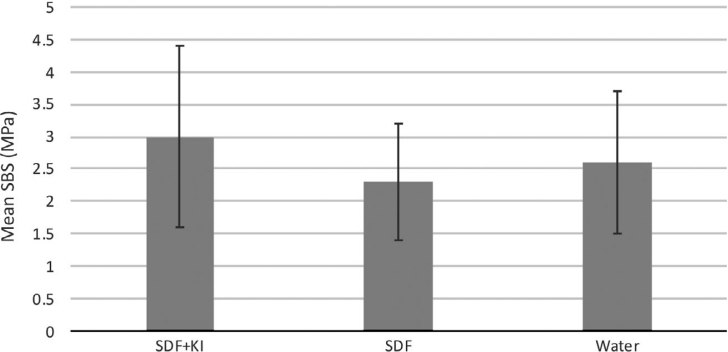

The mean bond strengths of GICs to dentine are shown in Figure 2 (n = 19 per group). Each group had one sample fractured pretest. The SBS (mean ± SD) for groups SDF + KI, SDF, and water were 3.0 ± 1.4 MPa, 2.3 ± 0.9 MPa and 2.6 ± 1.1 MPa, respectively (P = 0.217). The bond strengths of the three groups were not significantly different from each other.

Figure 2.

Mean SBS between GIC and dentine of the three groups (n = 19). No difference in mean SBS was found among the three groups (P = 0.217). GIC, glass ionomer cement; KI, potassium iodide; SBS, shear bond strength; SDF, silver diamine fluoride.

The failure modes of all samples are shown in Table 2. Cohesive failure was only observed within GICs but not in the demineralised dentine layer. No significant difference was found in the distribution of fracture modes for group SDF + KI, group SDF, and group water (P = 0.487). The general trend showed that cohesive failure within GICs was less frequent in the three groups compared with the other two failure types (P < 0.05). Representative SEM images of GIC–dentine interfaces are displayed in Figure 3.

Table 2.

The distribution of failure modes of the three groups (n = 19)

| Group | Failure modes (n) |

Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesive | Adhesive | Mixed | ||

| SDF + KI | 1 | 8 | 10 | 19 |

| SDF | 1 | 12 | 6 | 19 |

| Water | 2 | 12 | 5 | 19 |

KI, potassium iodide; SDF, silver diamine fluoride.

Figure 3.

Failure modes of dentine–glass ionomer cement (GIC) interface under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 1,000 × magnification. Adhesive failure: silver diamine fluoride (SDF) + potassium iodide (KI) (a1); SDF (a2); water (a3); mixed failure: SDF + KI (b1); SDF (b2); water (b3); cohesive failure: SDF + KI (c1); SDF (c2); water (c3).

DISCUSSION

This study first sought to investigate if pretreating caries-affected dentine with SDF + KI adversely affected adhesion of GICs to dentine. The results indicated no significant difference in SBS between the negative control group and the experimental groups (pretreatment with SDF or SDF + KI). In addition, SDF + KI treatment had no adverse colour effect on the surface of caries-affected dentine. The two null hypotheses were validated based on the findings of the current study. The clinical implications of these findings are that if KI is applied after the application of SDF to arrest or prevent dentine caries in a tooth, discolouration caused by SDF can be significantly reduced and bond strength to the caries-affected dentine of that tooth will not be affected. The current work was conducted in a controlled laboratory condition in which dentine was artificially demineralised to mimic caries-affected dentine. It is worth noting that natural caries-affected dentine, compared with demineralised dentine lesions, has a more complex microstructure. There may also be permeability differences between natural caries-affected dentine and artificial caries-affected dentine because the presence of mineral crystals in natural caries-affected dentine is considered to be effective in reducing fluid movement within dentinal tubules24. The two different substrates may therefore offer different conditions that will most likely lead to different adhesive properties. Furthermore, controlled laboratory conditions are different from the real oral environment. It is unclear whether the mechanical properties of GICs would be affected in a long-term exposure in the oral environment. Thus, caution should be taken when these findings are extrapolated to the clinical situation.

The traditional approach of managing cavitated carious lesions is to drill and fill, which refers to mechanically removing the soft and bacteria-infected dentine before filling the cavity with a proper restorative material. It is still reasonable to conduct the excavation because infected dentine is highly demineralised and physiologically not remineralisable based on the current evidence2. Nevertheless, there is evidence showing that removal of soft carious lesions may not be necessary. A clinical trial reported that no significant differences were found in the number of arrested tooth surfaces for children who had caries excavation prior to application of SDF compared with those that did not have caries removal16. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that bacterial count and activity were diminished over time if infected dentine in a cavitated caries lesion was restored with a well-sealed resin restoration2. From a biological view, the need of excavation prior to restoration or fluoride application is facing an intriguing challenge according to these findings. However, the need for caries excavation seems still to be controversial because it has been reported that the fracture strength of composite resin fillings may be compromised by the underlying soft, infected dentine25. On the contrary, caries-affected dentin structurally reserves enough collagen fibres to be remineralised and has a relatively low bacterial count. Dentine caries, which is either affected or arrested, tends to present a lower bacterial activity compared with infected dentin. Thus, caries removal is not needed prior to restorative filling for caries-affected dentine or for arrested lesions.

Silver diamine fluoride has been identified as a bactericidal chemical that can reduce the adherence and growth of cariogenic bacteria26. Moreover, it can be used to prevent the formation of secondary dentine caries around GIC restorations27. Thus, SDF can be a promising biological approach in the practice of minimally invasive dentistry against conventional restorative methods. The use of SDF, however, has been generally limited to primary teeth because of the discolouration effect associated with its application. According to the results of this study, SDF can be used as a liner so that the dentine base for the restoration does not contain viable bacteria. Because SDF can cause staining, an Australian group suggested using a saturated KI solution to mask the staining by reacting with silver ions14. Additionally, SDF + KI treatment has been investigated to be effective in increasing resistance to a cariogenic challenge27. SDF products that are readily commercially available were selected in this study to make the current work more relevant for dentists. SDF at a concentration of 38% is available as Saforide, Advantage Arrest and Riva Star. Saforide was chosen as the positive control in this study as it is the most commonly used SDF in previous clinical and laboratory studies. Riva Star is the only commercially available product of SDF + KI. Hence, it was selected as the experimental group.

It is important for patients to consider the aesthetic appearance of a restoration. In the present study, discolouration was evaluated quantitatively by instruments instead of the naked eyes, which is more accurate with high repeatability20. Metallic silver was formed by the reaction of SDF and hydroxyapatite, and its production was accelerated when exposed to light and high temperature26. This may be why SDF stains teeth black. It has been suggested that silver iodide (a bright-yellow solid compound) can be formed when KI solution reacts with SDF, and that the excess free silver ions that cause the black staining could be reduced by this reaction14. A higher lightness value and a perceptible total colour change (∆E) were detected on the caries-affected dentine in the SDF + KI treatment group in this study. The possible explanations may be that the formation of silver iodide attached to demineralised dentine surfaces that were relatively loosened and rough compared with normal dentine, even though the dentine surfaces were washed immediately after creamy white precipitates appeared according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Silver iodide, however, is believed to be highly photosensitive, and may dissociate into metallic silver and iodine by exposure to light. Ultimately, discolouration might still occur on tooth surfaces. Thus, the long-term effect of this treatment to eliminate staining, as well as its possible interaction with different restorative materials, needs to be determined.

Glass ionomer cements are regarded as one of the best options for fluoride-releasing restorative materials, which have been considered to be superior to compomers and giomers from the aspects of continuous fluoride release and recharge22. Nevertheless, the fluoride-releasing and anti-microbial effects of GICs are usually limited and insufficient. Hence, pretreating dentine surfaces with SDF or SDF + KI before GIC restoration has been proposed by some researchers14., 27. to enhance antimicrobial and remineralising ability of GICs. The results of this study demonstrated that pretreatment with SDF or SDF + KI did not adversely affect adhesion of the restoration to dentine, which is consistent with the previous findings of other laboratory studies2., 14.. Nevertheless, another study reported that there was an improvement in adhesion properties of fissure sealants applied after treating a tooth surface with SDF28. The differences in the outcomes may result from different techniques or different characteristics of tooth substrates. Cohesive failure within GICs was reported as the most common fracture mode in terms of adhesion between GICs and dentine in a previous study29, whereas this type of failure was less frequent than the other two failure modes in all groups in the present study. This variance might be explained by the different experimental conditions.

CONCLUSION

With the limitations of this laboratory study, the following conclusions were drawn. The immediate application of KI solution after SDF treatment can reduce dentine discolouration caused by SDF. Furthermore, SDF + KI treatment does not negatively affect bonding of GICs to artificial caries-affected dentine.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank HKU Gallant Ho Experiential Learning Centre for funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Irene Shuping Zhao, Email: zhao110@szu.edu.cn.

Edward Chin Man Lo, Email: hrdplcm@hku.hk.

References

- 1.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94:650–658. doi: 10.1177/0022034515573272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quock RL, Barros JA, Yang SW, et al. Effect of silver diamine fluoride on microtensile bond strength to dentin. Oper Dent. 2012;37:610–616. doi: 10.2341/11-344-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ericson D, Kidd E, McComb D, et al. Minimally invasive dentistry—concepts and techniques in cariology. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2003;1:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusayama T. Two layers of carious dentin; diagnosis and treatment. Oper Dent. 1979;4:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima M, Kunawarote S, Prasansuttiporn T, et al. Bonding to caries-affected dentin. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2011;47:102–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu CH, Lo EC. Promoting caries arrest in children with silver diamine fluoride: a review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu CH, Mei L, Seneviratne CJ, et al. Effects of silver diamine fluoride on dentine carious lesions induced by Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces naeslundii biofilms. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mei ML, Ito L, Cao Y, et al. An ex vivo study of arrested primary teeth caries with silver diamine fluoride therapy. J Dent. 2014;42:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mei ML, Ito L, Cao Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of silver diamine fluoride on dentine demineralisation and collagen degradation. J Dent. 2013;41:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei ML, Nudelman F, Marzec B, et al. Formation of fluorohydroxyapatite with silver diamine fluoride. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1122–1128. doi: 10.1177/0022034517709738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei ML, Ito L, Cao Y, et al. The inhibitory effects of silver diamine fluorides on cysteine cathepsins. J Dent. 2014;42:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.dos Santos VE, Jr, de Vasconcelos FM, Ribeiro AG, et al. Paradigm shift in the effective treatment of caries in schoolchildren at risk. Int Dent J. 2012;62:47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao SS, Zhao IS, Hiraishi N, et al. Clinical trials of silver diamine fluoride in arresting caries among children: a systematic review. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2016;1:201–210. doi: 10.1177/2380084416661474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight GM, McIntyre JM, Mulyani The effect of silver fluoride and potassium iodide on the bond strength of auto cure glass ionomer cement to dentine. Aust Dent J. 2006;51:42–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horst JA, Ellenikiotis H, et al. UCSF protocol for caries arrest using silver diamine fluoride: rationale, indications, and consent. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016;44:16–28. UCSF Silver Caries Arrest Committee. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu CH, Lo EC, Lin HC. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and sodium fluoride varnish in arresting dentin caries in Chinese pre-school children. J Dent Res. 2002;8:767–770. doi: 10.1177/0810767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yee R, Holmgren C, Mulder J, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for arresting caries treatment. J Dent Res. 2009;88:644–647. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaga M, Koide T, Hieda T. Adhesiveness of glass ionomer cement containing tannin-fluoride preparation (HY agent) to dentin—an evaluation of adding various ratios of HY agent and combination with application diamine silver fluoride. Dent Mater J. 1993;12:36–44. doi: 10.4012/dmj.12.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight GM, McIntyre JM, Craig GG, et al. An in vitro model to measure the effect of a silver fluoride and potassium iodide treatment on the permeability of demineralized dentine to Streptococcus mutans. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:242–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besinis A, De Peralta T, Handy RD. Inhibition of biofilm formation and antibacterial properties of a silver nano-coating on human dentine. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8:745–754. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.825343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akcay M, Arslan H, Yasa B, et al. Spectrophotometric analysis of crown discoloration induced by various antibiotic pastes used in revascularization. J Endod. 2014;40:845–848. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao IS, Mei ML, Zhou ZL, et al. Shear bond strength and remineralisation effect of a casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate-modified glass ionomer cement on artificial “caries-affected” dentine. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1723. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koizumi H, Hamama HH, Burrow MF. Evaluation of adhesion of a CPP-ACP modified GIC to enamel, sound dentine, and caries-affected dentine. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2016;66:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Li N, Qi Y, et al. The use of sodium trimetaphosphate as a biomimetic analog of matrix phosphoproteins for remineralization of artificial caries-like dentin. Dent Mater. 2011;27:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hevinga MA, Opdam NJ, Frencken JE, et al. Does incomplete caries removal reduce strength of restored teeth? J Dent Res. 2010;89:1270–1275. doi: 10.1177/0022034510377790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao IS, Gao SS, Hiraishi N, et al. Mechanisms of silver diamine fluoride on arresting caries: a literature review. Int Dent J. 2018;68:67–76. doi: 10.1111/idj.12320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao IS, Mei ML, Burrow MF, et al. Prevention of secondary caries using silver diamine fluoride treatment and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate modified glass-ionomer cement. J Dent. 2017;57:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-Hernández J, Aguilar-Díaz FC, Venegas-Lancón RD, et al. Effect of silver diamine fluoride on adhesion and microleakage of a pit and fissure sealant to tooth enamel: in vitro trial. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2018;19:411–416. doi: 10.1007/s40368-018-0374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanumiharja M, Burrow MF, Tyas MJ. Microtensile bond strengths of glass ionomer (polyalkenoate) cements to dentine using four conditioners. J Dent. 2000;28:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]