Abstract

Autosomal-dominant, Dutch-type cerebral amyloid angiopathy (D-CAA) offers a unique opportunity to develop biomarkers for pre-symptomatic CAA. We hypothesized that neuroimaging measures of white matter injury would be present and progressive in D-CAA prior to hemorrhagic lesions or symptomatic hemorrhage. In a longitudinal cohort of D-CAA carriers and non-carriers, we observed divergence of white matter injury measures between D-CAA carriers and non-carriers prior to the appearance of cerebral microbleeds and >14 years before the average age of first symptomatic hemorrhage. These results indicate that white matter disruption measures may be valuable cross-sectional and longitudinal biomarkers of D-CAA progression.

Introduction:

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a form of cerebral small vessel disease that is a common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage and a contributor to cognitive impairment1–3. CAA commonly co-occurs with parenchymal β-amyloid deposition (as in Alzheimer’s disease) but can also occur independently4. Although most cases of CAA are sporadic, several genetic variants in amyloid precursor protein (APP) have been shown to lead to autosomal dominant forms of CAA. The most common type is Dutch-type CAA (D-CAA) which is caused by a point mutation in APP (E693Q5). D-CAA becomes symptomatic at a younger age compared to the sporadic form yet presents with similar clinical and radiological manifestations as sporadic CAA6. By virtue of its early age of onset and complete penetrance, the study of D-CAA provides a unique window into pre-symptomatic CAA pathophysiology. D-CAA is a lethal, orphan disease for which there are few focused clinical trials. This is partly due to the difficulty in identifying suitable biomarkers of disease progression in early stages, prior to the emergence of cerebral hemorrhage. Building on prior cross-sectional work suggesting white matter disruption may occur prior to symptomatic hemorrhage in D-CAA7, we examined the progression of white matter changes in a longitudinal cohort of individuals with D-CAA. To investigate white matter changes, we used white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume and peak width of skeletonized mean diffusivity (PSMD) – a recently developed diffusion-based measure that is sensitive to cerebrovascular injury.

Methods:

Participants:

Neuroimaging data from 20 participants (9 D-CAA carriers, 11 non-carriers from the same families) in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN; NIA-U19-AG032438) were used in this study. Full procedures for DIAN are described elsewhere8,9. One participant in the non-carrier group had a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0.5. One D-CAA carrier had a CDR of 0 at baseline, but was CDR 0.5 at follow-up. All other participants were CDR=0 throughout the study. All study procedures received approval from participating institutions. Participants gave informed consent prior to the performance of any study procedures.

Image acquisition and processing:

The following MR images (3T) were used: 1) T1-weighted (T1w) MPRAGE: TR/TE/TI=2300/2.95/900ms, dimensions=1.1×1.1×1.2mm3; 2) 2D axial fluid attenuated recovery (FLAIR): TR/TE/TI=9000/91/2500ms, dimensions=0.86×0.86×5mm3; 3) 2D EPI diffusion tensor imaging (DTI): TR/TE=8100/87ms, dimensions=2.5×2.5×2.5mm3, number of directions=64, b-value=1000s/mm2; 4) Susceptibility weighted image: TR/TE=28/20ms, dimensions=0.7×0.7×2.4mm3 (baseline visits for all participants) or T2*-weighted gradient echo weighted image: TR/TE=650/20ms, dimensions=0.8×0.8×4mm3.

We segmented WMH on FLAIR images using the HyperMapp3r algorithm (https://hypermapp3r.readthedocs.io/). HyperMapp3r is a convolutional neural network-based segmentation algorithm that uses T1w, FLAIR, and brain mask images to generate WMH predictions in the T1w subject space. This pipeline outperforms other automated WMH segmentation procedures in quantifying deep and small WMH10. For illustrations of white matter lesions, WMH masks were co-registered to MNI standard space using the FLIRT tool (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FLIRT) in FSL6.0.1. Subsequently, a WMH probability map was created for baseline data of carriers to visualize the spatial pattern of lesions. Lastly, we calculated lobar WMH volumes using the MNI structural atlas.

We estimated PSMD from DTI using a publicly available script (http://www.psmdmarker.com)11. This pipeline preprocessed diffusion MRI (eddy current and motion correction) followed by tensor fitting, skeletonization of the data, and histogram analysis using FSL6.0.1 tools including Tract-Based Spatial Statistics procedure (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/TBSS) and fractional anisotropy template (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/Atlases,fsl).

Susceptibility weighted/T2*-weighted gradient echo images were visually inspected for the presence of sulcal blood and macro/microbleeds by radiologists at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester12,13. Small lesions (≤10mm) that were dissociable from small vessels were counted as definite microbleeds.

Statistical analyses:

Statistical analyses were performed in R (Version 4.0.2) and nominal p-values are reported. Independent t-test, Wilcoxon rank test, and chi-squared tests were used to compare D-CAA carrier and non-carrier demographics and clinical measures. Pearson correlations were used to investigate the association between the WMH volume (log-transformed to reduce skewness) and PSMD. Linear mixed-effect models assessed the longitudinal effects of D-CAA carriage and interactions with age for each marker. As in prior DIAN studies, we estimated the age of divergence between D-CAA carriers and non-carriers for WMH and PSMD using Hamiltonian Markov chain Monte Carlo analyses (http://mc-stan.org/). Subsequently, the distribution of parameter estimates across iterations was assessed to generate 95% credible intervals of the model fit. The age of divergence was determined as the point where 95% credible intervals of the difference distribution did not overlap 014.

Lastly, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses to 1) investigate regional specificity of WMH in differentiating carriers and non-carriers; 2) restrict analysis to only D-CAA carriers without any radiological evidence of macro/microbleeds; and 3) restrict analysis to only participants with a global CDR of zero.

Results:

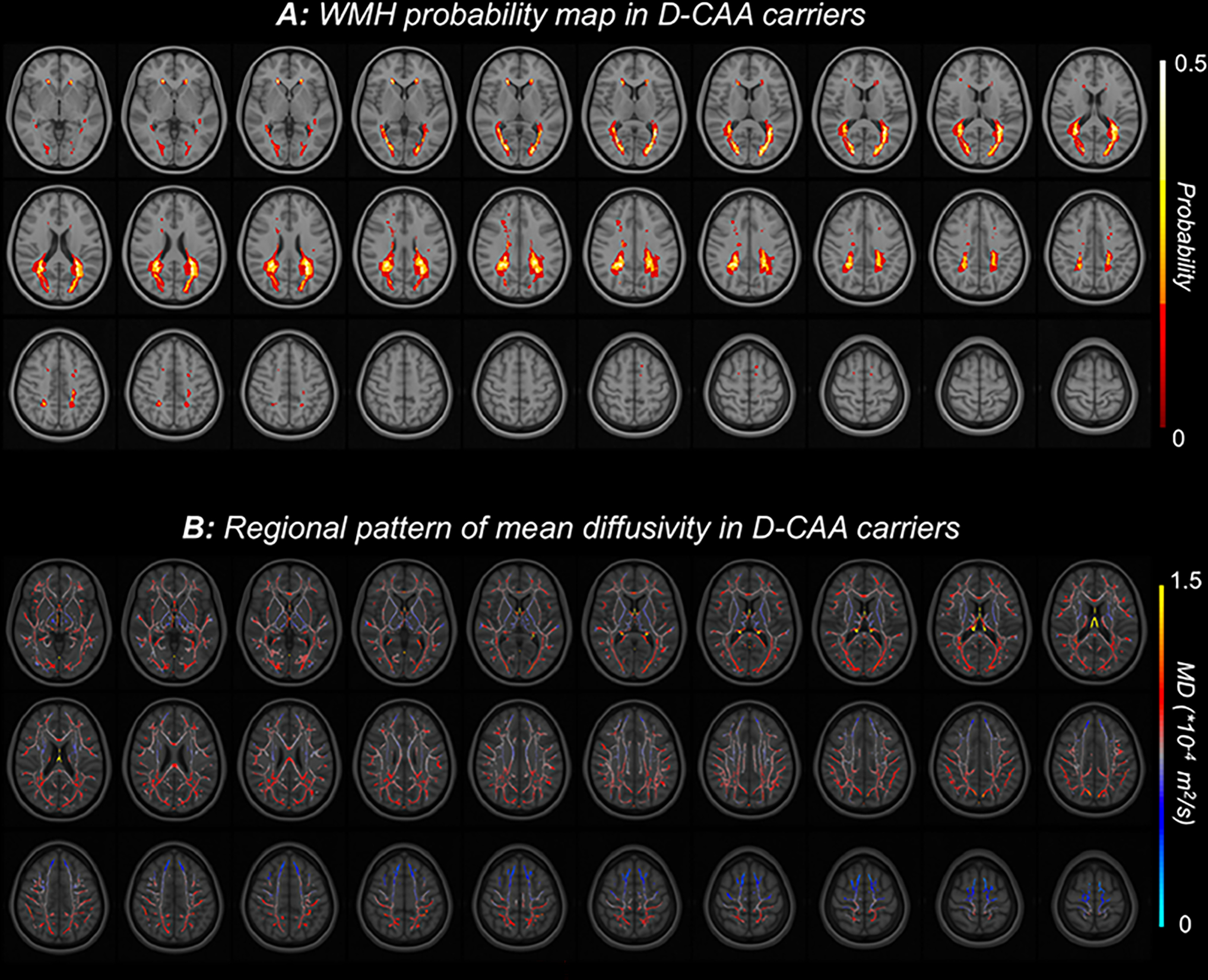

D-CAA carriers and non-carriers had similar demographics (Table1). The mutation carriers demonstrated periventricular WMH in posterior cortical regions while no deep WMH were observed (Figure1A). Similarly, higher levels of mean diffusivity were observed in the posterior regions (Figure1B). White matter measures were significantly different between carriers and non-carriers at baseline (Table 1, p<0.005). PSMD and WMH were strongly intercorrelated (r=0.8, p<0.001).

Table 1:

Participants’ demographics and study information. Mean ± Standard deviation or numbers are reported.

| D-CAA carrier (n=9) | D-CAA non-carrier (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | 44.9 ± 6.0 | 40.2 ± 8.3 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 6 / 3 | 7 / 4 |

| APOE e4 (−/+) | 8 / 1 | 8 / 3 |

| Education (years) | 14 ± 2.5 | 14 ± 3.0 |

| MMSE at baseline | 28.3 ± 1.4 | 28.5 ± 1.9 |

| MMSE at last visit | 28.6 ± 1.1 | 28.4 ± 1.6 |

| CDR-SOB at baseline (0 / 0.5) | 9 / 0 | 10 / 1 |

| CDR-SOB at last visit (0 / 0.5) | 8 / 1 | 10 / 1 |

| Follow-up time (years) | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 3.0 ± 2.3 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (yes/no) | 0 / 9 | 0 / 11 |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 1 / 8 | 3 / 8 |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 0 / 9 | 0 / 11 |

| Obesity (body mass index >35, yes/no) | 0 / 9 | 0 / 11 |

| WMH volume at baseline (mm3) | 6917 ± 9218 | 350 ± 419 |

| PSMD at baseline (×10−4 mm2/s) | 2.93 ± 0.6 | 2.26 ± 0.2 |

MMSE: Mini-mental state examination

CDR-SOB: Clinical dementia rating sum of the boxes

APOE e4 (−/+): Apolipoprotein E allele e4 status negative/positive

WMH: white matter hyperintensity

PSMD: Peak Width of Skeletonized Mean Diffusivity

Figure 1:

Spatial patterns of white matter injury in D-CAA. A: FLAIR-based white matter hyperintensity (WMH) probability map in D-CAA carriers showing a posterior predominance. Individual images were placed in MNI space, and voxels are colored by the probability of a white matter lesion being present in this cohort. B: Diffusion based mean diffusivity in the white matter skeleton. Individual mean diffusivity images were placed in MNI space, and voxels are colored by the average value across D-CAA carriers in this cohort.

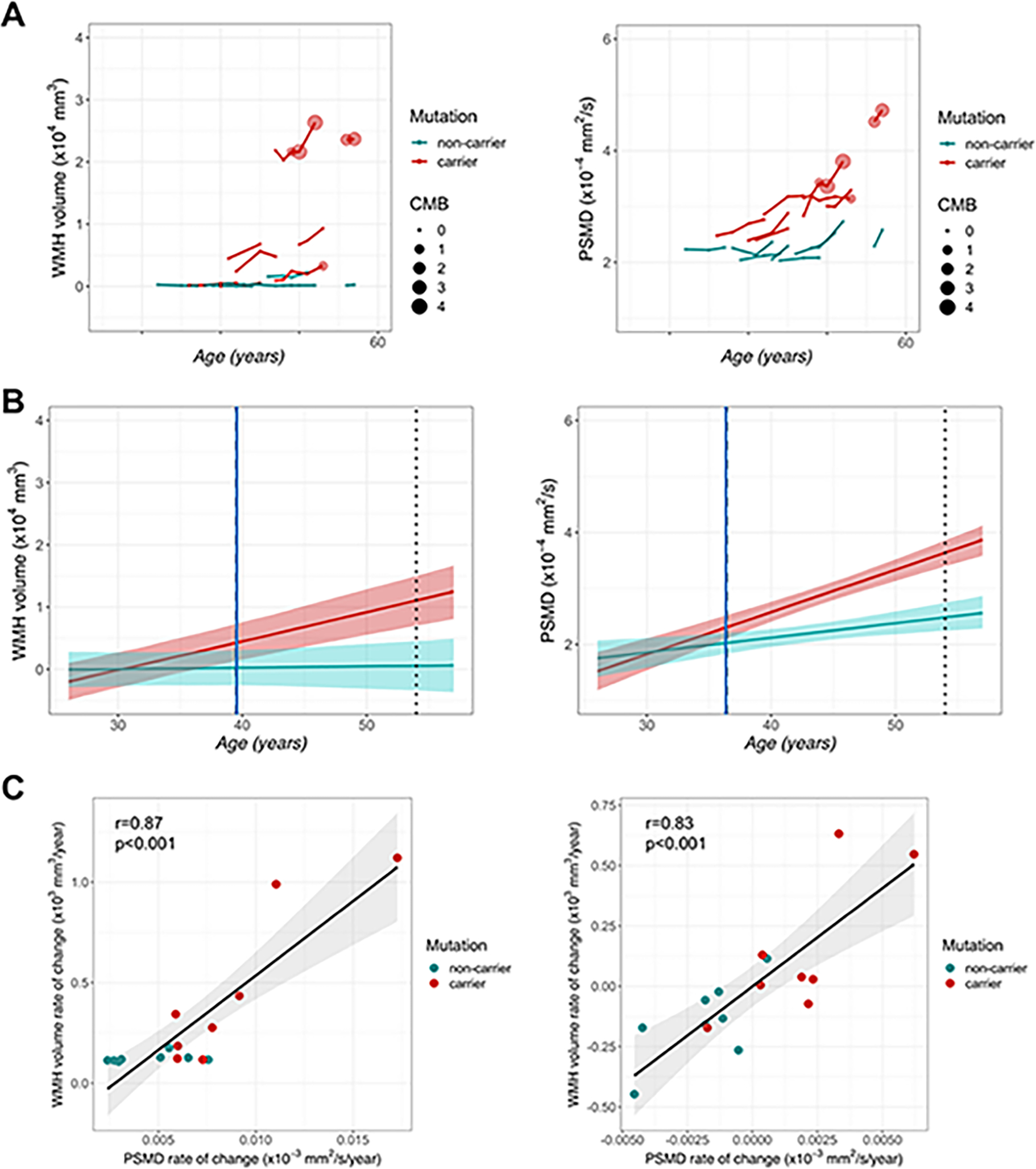

Rates of white matter change were assessed in participants with available longitudinal MRI (n=16, 8 carriers, 8 non-carriers, 52 annual visits). White matter injury measures increased over time, particularly in older D-CAA carriers (Figure2A). At a group level, rates of change in WMH and PSMD diverged between carriers and non-carriers at approximately age 40 (Figure2B), greater than 14 years prior to the average age of first symptomatic hemorrhage in D-CAA15 and >10 years prior to the age of first microbleed in this cohort (Figure2A). The predicted annual rate of change for carriers was 495 (95% confidence interval (CI): 258–756) mm3/year for WMH (t=3.4, df=14.3, p=0.004) and 5.2×10−6 (95% CI: 1.9 ×10−6-8.7 ×10−6) mm2/s/year for PSMD (t=2.5, df=11.8, p=0.02). The rates of change for WMH and PSMD were highly correlated (Figure2C).

Figure 2:

Longitudinal white matter measures. A: Measures of white matter injury in D-CAA mutation carriers and non-carriers are plotted over time, using age as a temporal reference. Lines shown connect measurements from an individual participant during longitudinal follow-up. Please note that exact ages are not shown to maintain blinding of D-CAA carrier status. The size of circles represents the number of definite cerebral microbleed (CMB) in each visit. B: Illustration of divergence analyses for D-CAA carriers (red) and non-carriers (teal). The standardized rate of change for each white matter measure based on model fit is depicted in each line. The blue solid line shows the age of divergence for each measure between D-CAA carriers and non-carriers while the dotted line indicates the average age of the first hemorrhage in D-CAA. The shaded area shows the 95% credible intervals for each model fit. C: The relationship between WMH and PSMD rate of change without (left) and with (right) adjustment for age.

In the sensitivity analysis, we observed no significant effect of D-CAA carriage in frontal and temporal lobes; in contrast, effects of carrier state were observed for WMH in occipital (t=2.5, p=0.02) and parietal (t=2.6, p=0.02) lobes.

Only one D-CAA carrier had radiological evidence of microbleed and sulcal blood at baseline; two other participants developed microbleeds at follow-up visits (Figure2A). Excluding these visits (n=15, number of observations=46) led to similar results with respect to rates of change in D-CAA carriers vs. non-carriers: WMH (t=2.8, df=5.1, p=0.03) and PSMD (t=3.1, df=33, p=0.004). Similarly, excluding visits at which participants had CDR=0.5 did not eliminate the observed effects (WMH: t=3.2, df=14.6, p=0.006; PSMD: t=4.4, df=40, p<0.001).

Discussion:

In this study, we observed clear signs of progressive white matter disruption visible on MRI in pre-symptomatic phases of D-CAA. This suggests that white matter injury in D-CAA precedes intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral microbleeds, and cognitive decline - cardinal CAA-associated events. The findings also suggest that white matter changes may be usable as a biomarker in pre-symptomatic D-CAA, a stage of disease that is relatively lacking in biomarker measures that can be employed in disease-modifying clinical trials. Patterns were similar across both FLAIR-based WMH and DTI-based PSMD. The longitudinal analyses recapitulated patterns seen in the cross-sectional data7 and demonstrated that rates of change in white matter measures diverged between D-CAA carriers and non-carriers more than a decade prior to symptomatic hemorrhage in D-CAA.

Despite similar trajectories, the white matter measures examined in this study represent potentially distinct forms of white matter injury. The posterior predominance for WMH and lack of deep lesions is in line with the recent finding in D-CAA that showed first cerebral hemorrhage in D-CAA is also more frequent in occipital lobe16. Moreover, prior reports demonstrated that blood vessel amyloid deposition in CAA may preferentially affect posterior brain regions17, and that posterior WMH are more closely related to elevated amyloid burden vs. higher cardiovascular risk in older adults18. In comparison, PSMD is thought to represent axonal and myelin loss19, and possible structural disconnection between brain regions. Compared to other DTI measures, PSMD may offer greater power in quantifying white matter changes that result from cerebral small vessel disease11. Importantly, these measures were obtained from fully automated and accessible processing pipelines thus can be easily implemented in clinical trial settings.

Though both measures showed strong cross-sectional and longitudinal effects, we found WMH had a slightly larger effect in differentiating D-CAA carriers and non-carriers. The strength with which WMH differentiated D-CAA carriers and non-carriers may have been enhanced by the low levels of WMH in the relatively young non-carrier population, providing a strong contrast. The findings here regarding early changes in white matter are consistent with neuropathological examinations of end-stage D-CAA20. These prior neuropathological findings together with the imaging findings here strongly suggest white matter changes are prominent in early and late phases of D-CAA and, further, that CAA physiology should potentially be considered in the differential diagnosis of white matter disease more broadly.

Notably, the sample size in this study is relatively small, as D-CAA is a rare condition. Despite the small sample size, the observed effects were robust and consistent across white matter measures, suggesting that markers of white matter change used here can potentially be employed as biomarker measures in clinical trials with a small number of participants.

Together, these results suggest that white matter injury occurs early in the D-CAA disease course and may provide powerful biomarkers for D-CAA clinical trials and research. Importantly, as the study of D-CAA can provide valuable insights into sporadic CAA, our findings strongly support assessing similar white matter changes in sporadic CAA.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Stroke (R01NS070834) and the National Institute on Aging (Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network; UF1AG032438; K23AG049087; P01AG036694). Zahra Shirzadi gratefully acknowledges a fellowship award from the Alzheimer’s Society of Canada that supported this work. Lastly, data collection for this study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council grant (APP1129627) to Ralph N. Martins.

This research was carried out in part at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41EB015896, a P41 Biotechnology Resource Grant supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health. This work also involved the use of instrumentation supported by the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant Program and/or High-End Instrumentation Grant Program; specifically, grant numbers S10RR021110, S10RR023401, and S10RR023043.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interests

There are no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this study.

References:

- 1.Charidimou A, Gang Q, Werring DJ. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2012;83(2):124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazim SF, Ogulnick JV, Robinson MB, et al. Cognitive Impairment After Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurgery 2021;148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology 2015;85(22):1930–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hernandez-Guillamon M, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease — one peptide, two pathways. Nature Reviews Neurology 2020;16(1):30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy E, Carman MD, Fernandez-Madrid IJ, et al. Mutation of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid gene in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage, Dutch type. Science 1990;248(4959):1124–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rooden S, van der Grond J, van den Boom R, et al. Descriptive analysis of the Boston criteria applied to a Dutch-type cerebral amyloid angiopathy population. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 2009;40(9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Rooden S, Van Opstal AM, Labadie G, et al. Early Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Cognitive Markers of Hereditary Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Stroke 2016;47(12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JC, Aisen PS, Bateman RJ, et al. Developing an international network for Alzheimer’s research: the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clinical Investigation 2012;2(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, et al. Clinical and Biomarker Changes in Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2012;367(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forooshani Parisa Mojiri and Biparva Mahdi and Ntiri Emmanuel E. and Ramirez Joel and Boone Lyndon and Holmes Melissa F. and Adamo Sabrina and Gao Fuqiang and Ozzoude Miracle and Scott Christopher J. M. and Dowlatshahi Dar and Lawrence-Dewar J M. Deep Bayesian networks for uncertainty estimation and adversarial resistance of white matter hyperintensity segmentation. bioRxiv 2021;2021.08.18.456666. http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2021/08/23/2021.08.18.456666.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baykara E, Gesierich B, Adam R, et al. A novel imaging marker for small vessel disease based on skeletonization of white matter tracts and diffusion histograms. Annals of Neurology 2016;80(4):581–592. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27518166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph-Mathurin N, Wang G, Kantarci K, et al. Longitudinal Accumulation of Cerebral Microhemorrhages in Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2021;96(12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kantarci K, Gunter J, Tosakulwong N, et al. Focal hemosiderin deposits and beta-amyloid load in the ADNI cohort. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2013;9(4S_Part_3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preische O, Schultz SA, Apel A, et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine 2019;25(2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Etten ES, Gurol ME, van der Grond J, et al. Recurrent hemorrhage risk and mortality in hereditary and sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2016;87(14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voigt S, Amlal S, Koemans EA, et al. Spatial and temporal intracerebral hemorrhage patterns in Dutch-type hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. International Journal of Stroke 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Orantes M, Wiestler OD. Vascular Pathology in Alzheimer Disease: Correlation of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Arteriosclerosis/Lipohyalinosis with Cognitive Decline. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 2003;62(12) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pålhaugen L, Sudre CH, Tecelao S, et al. Brain amyloid and vascular risk are related to distinct white matter hyperintensity patterns. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2021;41(5):1162–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Veluw SJ, Reijmer YD, van der Kouwe AJ, et al. Histopathology of diffusion imaging abnormalities in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2019;92(9): 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30700595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haan J, Roos RAC, Algra PR, et al. Hereditary cerebral haemorrhage with amyloidosis-dutch type: Magnetic RESONANCE imaging FINDINGS in 7 cases. Brain 1990;113(5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]