Abstract

Objective

Non-typhoidal Salmonellae (NTS) are a neglected group of enteric pathogens whose prevalence is increasing at alarming rates across India. The disease burden is being underestimated because of a lack of effective surveillance of NTS infections in the Indian population. This study depicts the acquisition of NTS infection, and its persistence and spread through a diverse range of hosts, including humans and animals, and food and environmental sources.

Methods

During the study period from 2016 to 2018, a total of 999 suspected NTS isolates were received from across India and were phenotypically and serologically characterized for the presence of NTS.

Results

Of the 999 isolates, 539 (53.95%) were confirmed as NTS, consisting of 17 different NTS serovars. The majority were isolated from human samples (n = 319, 59.18%), followed by food products (n = 99, 18.37%), animals (n = 83, 15.4%) and the environment (n = 38, 7.05%). Some predominant serovars obtained included S. Typhimurium (n = 167, 30.98%), S. Lindenberg (n = 135, 25.05%), S. Enteritidis (n = 56, 10.39%), S. Weltevreden (n = 44, 8.16%), S. Choleraesuis (n = 41, 7.61%) and S. Mathura (n = 33, 6.12%).

Conclusion

This study depicts the NTS disease burden across India, on the basis of the isolation of NTS serovars across diverse geographic locations. The emergence of newer or less common NTS serovars implicated in human infection poses a potential challenge to the healthcare system in India. Therefore, national and regional level surveillance is needed to implement effective control strategies and safeguard community health in India.

Keywords: Biotyping, Neglected enteric pathogens, Non-typhoidal Salmonella, NTS surveillance, Serotyping

Introduction

Salmonellae, a group of pathogenic bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, cause multiple enteric diseases in humans and are gaining attention in the scientific community worldwide because of their diverse associated diseases and treatment challenges in the developing world. The global annual disease burden of salmonella infections has been reported to be 3.4 million.1, 2, 3

The genus Salmonella is associated with various enteric diseases in humans, including typhoidal illness and non-typhoidal salmonellosis. Typhoid fever is caused primarily by S. enterica serovar Typhi and S. enterica serovar Paratyphi (A and B), whereas non-typhoidal illnesses are caused by a variety of other Salmonella serovars collectively known as non-typhoidal Salmonellae (NTS). NTS infections occur primarily through ingestion of food or water bearing these pathogens. Human and animal wastes are the major sources of contamination of food and environmental resources by NTS.4,5 Self-limiting diarrheal disease6 is the most frequent clinical manifestation due to NTS infection. In addition, the incidence of intestinal inflammation with diarrhea and extra-intestinal complications, such as bacteremia7 or invasive NTS disease, have also been reported.8,9

The distribution of NTS varies widely by time and location,10,11 and the host range is wide12,13 According to the World Health Organization,14 NTS are often distributed among wild and domestic animals, including poultry, pigs, cattle, cats, dogs, birds and reptiles. The major propagation routes arise from occupations involving the handling of animals and raw meat products. Unhygienic practices during the slaughtering of animals, and the handling and transportation of raw meat increase the likelihood of contamination of meat products with NTS.15,16 The survival and transmission of NTS through water bodies and the environment have also been reported.17,18

Although cases of NTS associated diarrhea most frequently occur in Asia, data and reports on NTS infections from India are lacking.7,19, 20, 21, 22 The pathogenic potential of Salmonellae is evolving at an alarming rate, and the actual NTS disease burden has been underestimated in India, owing to the absence of an effective nationwide surveillance system.19 A major challenge in combating the disease is tracking and controlling NTS dissemination. Therefore, epidemiological investigation of NTS is important to determine whether isolates recovered from different geographical locations are related, and to reveal common sources of transmission of the causative agents.23 The present study was therefore planned to study the prevalence of NTS isolates in different geographical locations across India.

Materials and Methods

Media and reagents

Media and biochemicals (Hi Media) in dehydrated form were used for identification of the bacterial isolates. Different H and O antigen specific antisera (monovalent and polyvalent) prepared at the Central Research Institute (CRI), Kasauli, HP, India, were used for serotyping of the isolates. In addition, some antisera obtained from Seiken Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan, were also used.

Sample collection

During the period from 2016 to 2018, the National Salmonella and Escherichia Coli Center (NSEC) at CRI, Kasauli, received 999 bacterial isolates suspected to be NTS , collected from various locations (including hospitals, agricultural and veterinary research institutes, and laboratories of fisheries/food departments) across India, for serovar confirmation. These isolates were primarily from human (blood, stool, urine, pus, tissue samples and body fluids) sources; animal sources, such as poultry and livestock (e.g., pig, cow or buffalo), comprising fecal, diarrheal and post-mortem samples; and food/environmental sources, including cow/buffalo-raw milk, animal/poultry-feed, raw meat (pork or chicken), eggs and seafood (fish or shrimp).

Characterization of bacterial isolates

The samples received in integral form (without leakage or breakage) under specified conditions were subjected to identification by biochemical and serological methods. Pure cultures of the isolates were obtained by streaking onto freshly prepared MacConkey agar (Hi Media Labs) plates. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, isolated, non-lactose fermenting colonies were sub-cultured aseptically on fresh nutrient agar slopes. Subsequently, each isolate was identified morphologically by Gram's staining, and motility was determined with the hanging drop method.

Biotyping

The biochemical characterization of the isolates was performed according to the standard procedure24, including tests such as indole, methyl red, Voges–Proskauer and citrate, enzyme detection tests (catalase, oxidase and urease production), sugar fermentation tests (glucose, sucrose, lactose, mannitol and dulcitol), substrate utilization tests (triple sugar iron) and decarboxylase tests (lysine, arginine and ornithine).

Serotyping

The serovar identification and antigenic profiling were performed with standard antisera and slide agglutination techniques,25,26 with some modifications. Briefly, a pure colony of the isolate was mixed in normal saline on a clean glass slide. The suspension was tested for agglutination with polyvalent O and H antisera. The serovar confirmation was performed with mono-specific antisera against O and H antigens.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 was used for the data processing and descriptive analysis to draw inferences regarding the prevalence of the different NTS serovars obtained from human, animal and environmental sources across the country. The data were graphically represented in MS Excel 2019.

Results

During the period from 2016 to 2018, a total of 999 suspected NTS isolates were received at NSEC from various regions of India for serovar confirmation. Of the 999 isolates received, 539 (53.95%) were biochemically and serologically confirmed as NTS; the remainder were found to be typhoidal Salmonellae (n = 98, 9.8%) and non-Salmonella (n = 362, 36.23%) isolates and were not included in the study (Table 1). Among these 539 NTS isolates, more NTS isolates (n = 323, 59.92%) were received during the year 2017 than 2016 (n = 109, 20.22%) or 2018 (n = 107, 19.85%).

Table 1.

Year-wise collection of bacterial isolates suspected to be non-typhoidal Salmonellae.

| Year | Total isolates received | Non-Salmonella isolates | Typhoidal Salmonellae | Non-typhoidal Salmonellae |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 289 (28.93%) | 168 (46.41%) | 12 (12.24%) | 109 (20.22%) |

| 2017 | 466 (46.65%) | 111 (30.66%) | 32 (32.65%) | 323 (59.92%) |

| 2018 | 244 (24.42%) | 83 (22.93%) | 54 (55.10%) | 107 (19.85%) |

| Total | 999 | 362 (36.23%) | 98 (9.81%) | 539 (53.95%) |

These NTS isolates were further divided into four categories according to the original source of isolation: 1) humans, 2) animals, 3) food products and 4) environment. Under the first category, the NTS were isolated from blood, CSF, feces, pus, sputum, urine and tissue samples. NTS from the feces of pigs, buffalos, cows and poultry constituted the second category of samples. NTS from pork, chicken, raw egg, animal feed, milk, fish and other seafoods were grouped under the third category. All environmental isolates were designated under the fourth category.

A region-wise analysis of the sources of isolation of these 539 NTS isolates revealed that most (n = 319, 59.18%) were isolated from human samples, followed by food products (n = 99, 18.37%), animals (n = 83, 15.40%) and the environment (n = 38, 7.05%) (Table 2). The table also depicts the region-wide distribution. Most NTS isolates (n = 313, 58.07%) were received from Southern India, and other regions contributed between 0.37% and 18.18% of the total NTS collection.

Table 2.

Region vs. source distribution of NTS collected during the period from 2016 to 2018.

| Region of India | Source of NTS |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Food products | Animal | Environment | ||

| Central | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.37%) |

| East | 0 | 16 | 17 | 4 | 37 (6.86%) |

| North | 24 | 29 | 45 | 0 | 98 (18.18%) |

| South | 289 | 3 | 21 | 0 | 313 (58.07%) |

| West | 4 | 51 | 0 | 34 | 89 (16.51%) |

| Total | 319 (59.18%) | 99 (18.37%) | 83 (15.4%) | 38 (7.05%) | 539 |

The serotyping of these 539 NTS isolates confirmed the presence of 17 different NTS serovars, which are listed in descending order of occurrence in Table 3. The six NTS serovars—S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 167, 30.98%), S. enterica serovar Lindenberg (n = 135, 25.05%), S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (n = 56, 10.39%), S. enterica serovar Weltevreden (n = 44, 8.16%), S. enterica serovar Choleraesuis (n = 41, 7.61%) and S. enterica serovar Mathura (n = 33, 6.12%)—were collectively found to be the predominant serovars, representing 88.3% of the total NTS isolates in this study. The remaining 11 serovars contributed between 0.19% and 2.23%, and accounted for 11.7% of the total NTS serovars obtained in this study.

Table 3.

Total numbers of NTS isolates obtained.

| Name of organism | Antigenic structure (somatic O antigen: H phase I: phase II) | Number of isolates | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | 4,12: i: 1,2 | 167 | 30.98% |

| S. enterica serovar Lindenberg | 6,8: i: 1,2 | 135 | 25.05% |

| S. enterica serovar Enteritidis | 9,12: g,m: - | 56 | 10.39% |

| S. enterica serovar Weltevreden | 3,10: r: Z6 | 44 | 8.16% |

| S. enterica serovar Choleraesuis | 6,7: c: 1,5 | 41 | 7.61% |

| S. enterica serovar Mathura | 9,46: i: e, n, Z15 | 33 | 6.12% |

| S. enterica serovar Anatum | 3,10: e, h:1,6 | 12 | 2.23% |

| S. enterica serovar Jaffna | 9,12: d: Z39 | 10 | 1.86% |

| S. enterica serovar Tennessee | 6,7: Z29: - | 09 | 1.67% |

| S. enterica serovar Stuttgart | 6,7: i: Z6 | 08 | 1.48% |

| S. enterica serovar Kentucky | 8,20: i: Z6 | 06 | 1.11% |

| S. enterica serovar Bazenheid | 8,20: Z10: 1,2 | 04 | 0.74% |

| S. enterica serovar Hissar | 6,7: c: 1,2 | 04 | 0.74% |

| S. enterica serovar Virchow | 6,7: r: 1,2 | 04 | 0.74% |

| S. enterica serovar Poona | 13,22: z: 1,6 | 03 | 0.56% |

| S. enterica serovar Senftenberg | 1,3,19: g,t: - | 02 | 0.37% |

| S. enterica serovar Ughelli | 3,10: r: 1,5 | 01 | 0.19% |

| Total number of NTS isolates | 539 | ||

Among these 17 NTS serovars, ten were isolated from human samples (Figure 1). S. enterica serovar Lindenberg (n = 103, 32.3%) was the dominant serovar. The other NTS serovars frequently encountered were S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 89, 27.9%), S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (n = 50, 15.7%), S. enterica serovar Choleraesuis (n = 40, 12.5%) and S. enterica serovar Weltevreden (n = 21, 6.6%). Collectively, these five serovars accounted for 95% of the total NTS serovars isolated from human samples. The remaining 5% included S. enterica serovar Jaffna, S. enterica serovar Poona, S. enterica serovar Mathura and S. enterica serovar Ughelli.

Figure 1.

NTS isolates obtained from human samples.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 32, 38.6%) was the major serovar among the ten NTS serovars isolated from animals (Figure 2). The other four major NTS serovars were S. enterica serovar Lindenberg (n = 11, 13.3%), S. enterica serovar Weltevreden (n = 9, 10.8%), S. enterica serovar Stuttgart (n = 8, 9.6%) and S. enterica serovar Mathura (n = 7, 8.4%). Collectively, these five serovars represented 80.7%, and the remaining five NTS serovars—S. enterica serovar Anatum, S. enterica serovar Tennessee, S. enterica serovar Bazenheid, S. enterica serovar Enteritidis and S. enterica serovar Senftenberg—accounted for 19.3% of the total isolates obtained from animals.

Figure 2.

NTS isolates obtained from animals.

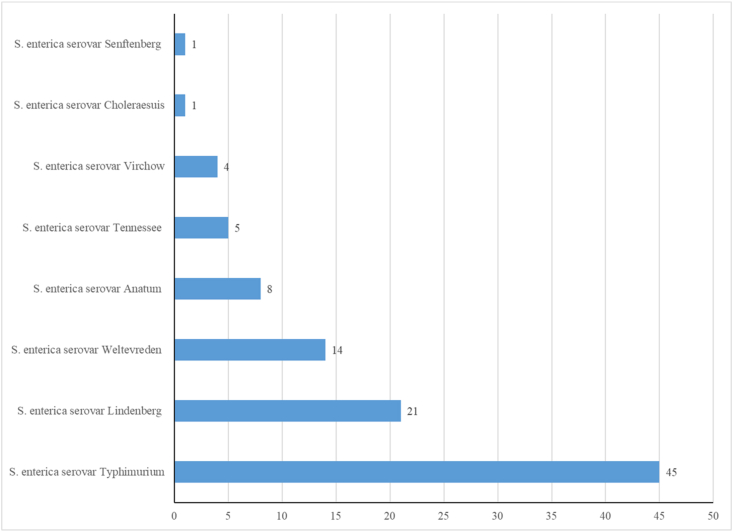

Similarly, among the eight NTS serovars obtained from food samples (Figure 3), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 45, 45.5%), S. enterica serovar Lindenberg (n = 21, 21.2%) and S. enterica serovar Weltevreden (n = 14, 14.1%) were the dominant NTS serovars, composing 80.8% of the total. The remaining five serovars individually contributed between 1.0% and 8.1%.

Figure 3.

NTS isolates obtained from food products.

Among the five NTS isolates obtained from environmental samples, S. enterica serovar Mathura (n = 25, 65.8%) was the only serovar that predominated over the other NTS isolates (Figure 4). The other four serovars were S. enterica serovar Jaffna (n = 5, 13.2%), S. enterica serovar Hissar (n = 4, 10.5%), S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (n = 3, 7.9%) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 1, 2.6%).

Figure 4.

NTS isolates obtained from environmental samples.

Discussion

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis poses a major threat to human health, because of its increased global incidences arising from its persistence and spread in diverse hosts including humans and animals, and sources including food and the environment, which are interrelated through frequent interactions and thereby maintain a natural transmission cycle. Globally, an estimated 93 million enteric infections occur annually because of NTS, causing 155,000 deaths.27

In the literature on NTS infection in India, several authors have published their findings on NTS infection at different time points.3,28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The prior studies have focused mainly on particular geographic areas of the country and consequently have not provided a clear picture of prevalence of NTS infection across India. Therefore, the present research was aimed at studying the distribution of NTS over diverse geographical locations across India, to assess the NTS disease burden throughout the country. In the present study, suspected NTS isolates from 13 Indian states, collected from different sources including hospitals, agricultural research institutes and food research laboratories, were included in the analysis. Of the total NTS isolates confirmed in this study, 59.18% were from human samples, 18.37% were from food products, 15.4% were from animals, and 7.05% were from environmental sources. Of the 17 NTS serovars obtained from humans or animals, and food/environmental samples, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was the most frequently occurring NTS serovar, followed by S. enterica serovar Lindenberg, S. enterica serovar Enteritidis, S. enterica serovar Weltevreden and S. enterica serovar Mathura in decreasing order of occurrence. Of note, these pathogens have been reported to be associated with clinical illness in humans, beyond their routine isolation from animal, food or environmental sources, thereby indicating a possible role of these reservoirs in the transmission of NTS to humans, in agreement with prior studies.16,33

In this study, as previously reported,34, 35, 36 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was the most frequently isolated NTS serovar, followed by S. enterica serovar Lindenberg.14,37 The highly prevalent serovar S. enterica serovar Typhimurium has already been reported to be an invasive NTS serovar globally.6 The serovar Lindenberg was first reported to be isolated from a human blood sample in 20183 in India. In this study, one isolate each of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and S. enterica serovar Lindenberg was obtained from human CSF; this important finding indicates the invasive nature of these bacteria, thus raising concerns regarding possible threats to community health.

S. enterica serovar Enteritidis is a common serovar causing invasive human infections10,38 in India and worldwide. In our study, most (n = 50, 15.67%) of the S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates were obtained from human samples (including blood, pus, feces, urine and tissue), whereas only three isolates each were from animal and environmental sources—a previously unreported finding.

NTS serovar S. enterica serovar Weltevreden has been significantly associated with zoonotic infections in India over many decades.39, 40, 41 In this study, this NTS serovar was obtained primarily from fecal samples from humans and animals, and also from raw cow/buffalo milk. One isolate each was from human blood and tissue samples, thereby indicating possible systemic infection with this serovar.

S. enterica serovar Mathura was first reported to be isolated from cattle in Mathura,42 a town in northern India. In this study, most of the S. enterica serovar Mathura isolates were from environmental samples (n = 25, 65.79%) and poultry (n = 7, 8.43%), whereas one isolate was obtained from human blood. This study provides the first report of S. enterica serovar Mathura in humans. According to the data available, the source of transmission of this serovar to humans cannot be ascertained. To date, no literature is available from India or any other country regarding the isolation of S. enterica serovar Mathura serovar from humans. Although the isolation rate reported in this study is less than 1%, further studies in this regard must be done to study the epidemiological role of this NTS serovar in human infection.

Conclusion

This study reports the isolation of NTS from diverse sources and geographical locations across India. S. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Lindenberg and Weltevreden were the three major NTS serovars commonly isolated from samples originating from humans, animals and food products. Moreover, the same NTS serovars came from different sources across diverse geographic locations of the country, thereby suggesting that these serovars are not host specific and may be present in a variety of hosts. However, further studies at the genetic level should be conducted to establish the relationships between hosts and NTS serotypes. In addition, some less common NTS serovars, such as S. enterica serovar Mathura, S. enterica serovar Jaffna, S. enterica serovar Ughelli and S. enterica serovar Poona, were also isolated from human samples. The addition of these newer or less common serovars to the existing list of NTS serovars known to cause disease in humans indicates a major challenge to the health care system in India. Furthermore, the possibility of the existence or emergence of many more uncommon NTS serovars in the future cannot be ruled out, because these serovars could substantially increase the NTS disease burden in the country. Our findings underscore the need to effectively implement and enhance NTS surveillance; detect the presence of newer NTS serovars; identify the reservoirs and modes of transmission; and develop control programs including impact assessment. Finally, national and regional level monitoring programs are needed to implement effective control strategies to eliminate the threat to community health in India from NTS, a neglected group of enteric pathogens.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Authors contributions

SK conducted the research, organized and analyzed the data, and wrote the initial and final drafts of the manuscript. Gu K provided research support. Ga K and YK supervised the research. AK provided all research materials and support for this research. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all hospitals, laboratories and research centers that submitted Salmonella isolates for serotyping at NSEC, CRI, Kasauli. The authors also thank the staff of NSEC and the Diagnostic Reagent (DR) Laboratory, CRI, Kasauli, for support during this work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Ao T.T., Feasey N.A., Gordon M.A., Keddy K.H., Angulo F.J., Crump J.A. Global burden of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Jun;21(6):941. doi: 10.3201/eid2106.140999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanaway J.D., Parisi A., Sarkar K., Blacker B.F., Reiner R.C., Hay S.I., et al. The global burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudhaharan S., Kanne P., Vemu L., Bhaskara A. Extraintestinal infections caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella from a tertiary care center in India. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10(4):401–405. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_79_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponce E., Khan A.A., Cheng C.M., Summage-West C., Cerniglia C.E. Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Weltevreden from imported seafood. Food Microbiol. 2008;25(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thong K.L., Goh Y.L., Radu S., Noorzaleha S., Yasin R., Koh Y.T., et al. Genetic diversity of clinical and environmental strains of Salmonella enterica serotype Weltevreden isolated in Malaysia. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(7):2498–2503. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2498-2503.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasubramanian R., Im J., Lee J.S., Jeon H.J., Mogeni O.D., Kim J.H., et al. The global burden and epidemiology of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15(6):1421–1426. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1504717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballal M., Devadas S.M., Shetty V., Bangera S.R., Ramamurthy T., Sarkar A. Emergence and serovar profiling of non-typhoidal Salmonellae (NTS) isolated from gastroenteritis cases – a study from South India. Infect Dis. 2016;48(11–12):847–851. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2016.1169553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feasey N.A., Dougan G., Kingsley R.A., Heyderman R.S., Gordon M.A. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet. 2012;379(9835):2489–2499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crump J.A., Heyderman R.S. A perspective on invasive Salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl. 4):S235–S240. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendriksen R.S., Vieira A.R., Karlsmose S., Lo Fo Wong D.M., Jensen A.B., Wegener H.C., et al. Global monitoring of Salmonella serovar distribution from the World Health Organization Global Foodborne Infections Network Country Data Bank: results of quality assured laboratories from 2001 to 2007. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8(8):887–900. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van T.T., Nguyen H.N., Smooker P.M., Coloe P.J. The antibiotic resistance characteristics of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica isolated from food-producing animals, retail meat and humans in South East Asia. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;154(3):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon M.A. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(5):484–489. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a9980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguire H.C.F., Codd A.A., Mackay V.E., Rowe B., Mitchell E. A large outbreak of human salmonellosis traced to a local pig farm. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110(2):239–246. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800068151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salmonella (non-typhoidal) n.d. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/salmonella-(non-typhoidal), [accessed 25.05.21].

- 15.Gillespie I.A., O'Brien S.J., Adak G.K., Ward L.R., Smith H.R. Foodborne general outbreaks of Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 4 infection, England and Wales, 1992–2002: where are the risks? Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(5):795–801. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805004474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng S.K., Pusparajah P., Ab Mutalib N.S., Ser H.L., Chan K.G., Lee L.H. Salmonella: a review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front Life Sci. 2015;8:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levantesi C., Bonadonna L., Briancesco R., Grohmann E., Toze S., Tandoi V. Salmonella in surface and drinking water: occurrence and water-mediated transmission. Food Res Int. 2012;45(2):587–602. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee N., Nolan V.G., Dunn J.R., Banerjee P. Exposures associated with non-typhoidal Salmonella infections caused by Newport, Javiana, and Mississippi serotypes in Tennessee, 2013–2015: a case-case analysis. Pathogens. 2020;9(2):78. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudhanthirakodi S. Non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from livestock and food samples, in and around Kolkata, India. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;6(3):113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menezes G.A., Khan M.A., Harish B.N., Parija S.C., Goessens W., Vidyalakshmi K., et al. Molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance in non-typhoidal salmonellae associated with systemic manifestations from India. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59(12):1477–1483. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.022319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taneja N., Appannanavar S.B., Kumar A., Varma G., Kumar Y., Mohan B., et al. Serotype profile and molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella isolated from gastroenteritis cases over nine years. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(1):66–73. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.061416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung D.T., Das S.K., Malek M.A., Ahmed D., Khanam F., Qadri F., et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis at a diarrheal hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1996-2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88(4):661–669. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang H.P., Dunne W.M. Stability of repetitive-sequence PCR patterns with respect to culture age and subculture frequency. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2694–2696. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2694-2696.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewing W.H. 4th ed. Elsevier; New York: 1986. Edwards and Ewing's identification of Enterobacteriaceae. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriksen R., Larsen J. 6th ed. 2004. Global Salm-Surv – a global Salmonella surveillance and laboratory support project of the World Health Organization. (Laboratory protocols – serotyping of Salmonella enterica O and H antigen). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimont P.A., Weill F.X. vol. 2. 2007. Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars; pp. 1–166. (WHO collaborating centre for reference and research on Salmonella). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majowicz S.E., Musto J., Scallan E., Angulo F.J., Kirk M., O'Brien S.J., et al. International Collaboration on Enteric Disease “Burden of Illness” Studies The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):882–889. doi: 10.1086/650733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saravanan S., Purushothaman V., Murthy T.R., Sukumar K., Srinivasan P., Gowthaman V., Balusamy M., Atterbury R., Kuchipudi S.V. Molecular epidemiology of Nontyphoidal Salmonella in poultry and poultry products in India: implications for human health. Indian J Microbiol. 2015;55(3):319–326. doi: 10.1007/s12088-015-0530-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma J., Kumar D., Hussain S., Pathak A., Shukla M., Kumar V.P., Anisha P.N., Rautela R., Upadhyay A.K., Singh S.P. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes characterization of nontyphoidal Salmonella isolated from retail chicken meat shops in Northern India. Food Control. 2019;102:104–111. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pragasam A.K., Anandan S., John J., Neeravi A., Narasimman V., Sethuvel D.P., Elangovan D., Veeraraghavan B. An emerging threat of ceftriaxone-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella in South India: incidence and molecular profile. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37(2):198–202. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_19_300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob J.J., Solaimalai D., Sethuvel D.P., Rachel T., Jeslin P., Anandan S., Veeraraghavan B. A nineteen-year report of serotype and antimicrobial susceptibility of enteric non-typhoidal Salmonella from humans in Southern India: changing facades of taxonomy and resistance trend. Gut Pathog. 2020;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13099-020-00388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain P., Chowdhury G., Samajpati S., Basak S., Ganai A., Samanta S., Okamoto K., Mukhopadhyay A.K., Dutta S. Characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from children with acute gastroenteritis, Kolkata, India, during 2000–2016. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51(2):613–627. doi: 10.1007/s42770-019-00213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng X., Ran L., Wu S., Ke B., He D., Yang X., et al. Laboratory-based surveillance of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Guangdong Province, China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9(4):305–312. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saxena S.N., Mago M.L., Rao Bhau L.N., Ahuja S., Singh H. Salmonella serotypes prevalent in India during 1978-81. Indian J Med Res. 1983;77:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar Y., Sharma A., Sehgal R., Kumar S. Distribution trends of Salmonella serovars in India (2001-2005) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(4):390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar R., Surendran P.K., Thampuran N. Distribution and genotypic characterization of Salmonella serovars isolated from tropical seafood of Cochin, India. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;106(2):515–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhurajan R., Kiran R., Padmavathy K. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Salmonella Lindenberg gastroenteritis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2019;13(9):851–853. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suresh T., Hatha A.A., Sreenivasan D., Sangeetha N., Lashmanaperumalsamy P. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enteritidis and other salmonellas in the eggs and egg-storing trays from retails markets of Coimbatore, South India. Food Microbiol. 2006;23(3):294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basu S., Sood L.R. Salmonella Weltevreden: a sero-type of increasing public health importance in India. Trop Geogr Med. 1975;27(4):387–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patil A.B., Krishna B.V., Chandrasekhar M.R. Case report. Neonatal sepsis caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Weltevreden. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37(6):1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antony B., Dias M., Shetty A.K., Rekha B. Food poisoning due to salmonella enterica serotype Weltevreden in Mangalore. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27(3):257–258. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.53211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lapage S.P., Taylor J., Nicewonger C.R., Phillips A.G. New serotypes of Salmonella identified before 1964 at the Salmonella reference laboratory, Colindale. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1966;16(3):253–298. [Google Scholar]