Abstract

Background:

Age and ethnicity are among several factors that influence overall survival (OS) in ovarian cancer. The study objective was to determine whether ethnicity and age were of prognostic significance in women enrolled in a clinical trial evaluating the addition of bevacizumab to front-line therapy.

Methods:

Women with advanced stage ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer were enrolled in a phase III clinical trial. All women had surgical staging and received adjuvant chemotherapy with one of three regimens. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the relationship between OS with age and race/ethnicity among the study participants.

Results:

One-thousand-eight-hundred-seventy-three women were enrolled in the study. There were 280 minority women and 328 women over the age of 70. Women age 70 and older had a 34% increase risk for death when compared to women under 60 (HR=1.34; 95% CI 1.16–1.54). Non-Hispanic Black women had a 54% decreased risk of death with the addition of maintenance bevacizumab (HR=0.46, 95% CI:0.26–0.83). Women of Asian descent had more hematologic grade 3 or greater adverse events and a 27% decrease risk of death when compared to non-Hispanic Whites (HR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.59-.90).

Conclusions:

Non-Hispanic Black women showed a decreased risk of death with the addition of bevacizumab and patients of Asian ancestry had a lower death rate than all other minority groups, but despite these clinically meaningful improvements there was no statistically significant difference in OS among the groups.

Keywords: Minority populations, Asian women, African American women, elderly, ovarian cancer, bevacizumab

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 60% of women affected with epithelial ovarian cancer will present with advanced stage disease [1]. While much has been done to improve the treatment of this disease, overall survival (OS) for advanced stage disease is approximately 30% [1–3]. Prior studies have established age, stage, volume of residual disease, histology, and performance status as prognostic factors for epithelial ovarian cancer [4–6]. In addition to these prognostic factors, racial and ethnic disparities have been reported as an important factor in ovarian cancer survival [7–9]. When ovarian cancer survival data is examined from national databases OS is shorter among Black and Hispanic women when compared to White women [7–13]. These differences are due partly to the lack of access to high volume providers and insurance status [7–19]. However, several studies from large clinical trials show that when treatment factors are equal there is no difference in survival between Black and White women [15, 20–21]. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) published two similar retrospective analyses of six phase III clinical trials in White and Black patients [5, 22]. These two studies evaluated the same series of patients and categorized patients as Black, White, or other [5, 22]. Women in these trials received paclitaxel and a platinum-based regimen and no difference in OS was seen among these two racial groups [5, 22]. However, these studies limited their analyses to mainly Black and White patients [5, 22]. The purpose of the current study is to evaluate the prognostic significance of ethnicity and age in women enrolled in the context of a large phase III clinical trial.

Materials and Methods

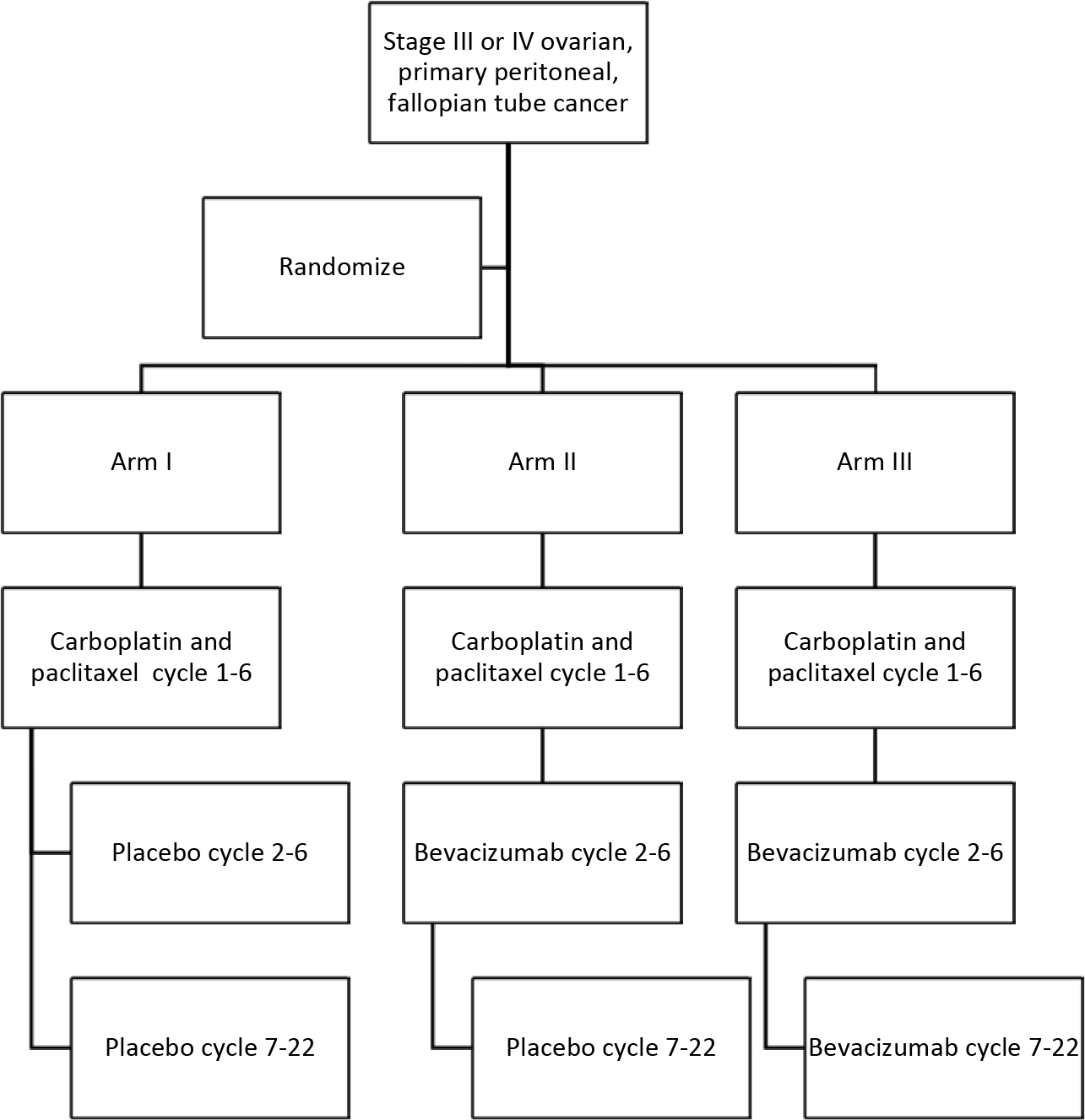

Women with surgically staged epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer were enrolled in GOG-218, a phase III clinical trial, and randomized to one of three treatment regimens (Figure 1). Women in the control arm received adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel for 6 cycles followed by 16 cycles of placebo every 4 weeks. Women randomized to arm II received adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel for 6 cycles with the addition of bevacizumab starting with the second cycle of chemotherapy for a total of 5 cycles. Patients in arm II received placebo for an additional 16 cycles after the completion of primary therapy. Patients in arm III received the same chemotherapy as patients in arm II but with the addition of bevacizumab maintenance therapy for 16 cycles after the completion of primary therapy with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. The details of the eligibility criteria and chemotherapy regimens have been previously published [23]. All patients gave written informed consent before enrollment.

Figure 1.

Schema for Gynecologic Oncology Group protocol 218.

An analysis of patients enrolled in GOG-218 was conducted to evaluate the prognostic significance of race and ethnicity, and age on treatment outcomes and OS. Follow-up data was frozen as of January 16, 2018.

The cumulative probability distributions of survival times were estimated with Kaplan-Meier procedures [24]. Differences in OS were assessed with the log-rank test. Duration of survival for each patient was calculated from the date of entry onto the study until the date of death, regardless of the cause of death. For those women who were alive at last contact, the time at risk of death was calculated up to the date of last contact. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the relative hazards of death for subgroups of patients [25]. Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate grade 3 toxicity by age and grade 3 toxicity by race/ethnicity. The Kruskal-Wallis rank test was used to compare patient subgroups with respect to age [26]. The presented p-values are nominal and do not account for testing multiple hypotheses. Finally, a test of interaction was used to assess for differences in treatment effect on OS in race/ethnicity groups and age groups.

RESULTS

One-thousand-eight-hundred-seventy-three women were enrolled in GOG-218 and 14.9% of the patients were of a racial or ethnic minority (Table 1). Three-hundred and twenty-eight women were age 70 or older and 32 women were age 80 or older. The characteristics of enrolled patients by age group are described in Table 2. Eighty-five percent of the patients enrolled had papillary serous histology. The distribution of age at diagnosis varied by primary site of cancer (p<0.001) with women diagnosed with primary peritoneal cancer (median age=64.6) being older than women with ovarian cancer (median age=59.1) or fallopian tube cancer (median age=61.3). Women diagnosed with a transitional cell carcinoma tended to be younger (median age=52.2) than women diagnosed with serous (median age=60.7) or endometrioid (median age=58.3) histology, p<0.001. Ninety-percent of women ages 70 or older had a GOG performance status of 0 or 1 compared to 95% of women who were <60 (Table 2). Therefore, increasing age correlated with a decrease in performance status (p<0.001). The distribution of age at diagnosis varied by race and ethnicity separately (p<0.001 for both).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by race and ethnicity.

| Patient characteristic | NH-White n % | NH-Black n % | Hispanic n % | Asian/Pacific Islander n % | Other n % | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Treatment | CTP- > Placebo | 526 (33.6) | 25 (31.3) | 21 (28.4) | 46 (36.5) | 7 (25.9) | 625 |

| CTB- > Placebo | 519 (33.1) | 28 (35.0) | 28 (37.5) | 39 (31.0) | 11 (40.7) | 625 | |

| CTB- > Bevacimmab | 521 (33.3) | 27 (33.8) | 25 (33.5) | 41 (32.5) | 9 (33.3) | 623 | |

| Age Cioup | <60 years | 752 (48.0) | 38 (475) | 51 (68.9) | 80 (63.5) | 14 (51.9) | 935 |

| 60–69 years | 518 (33.1) | 32 (40.0) | 14 (18.5) | 38 (30.2) | 8 (29.6) | 610 | |

| ≥70 years | 296 (18.9) | 10 (12.5) | 9 (12.2) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (18.5) | 328 | |

| Performance Status | 0 | 761 (48.6) | 41 (51.3) | 37 (50.0) | 81 (64.3) | 11 (40.7) | 931 |

| 1 | 697 (44.5) | 31 (38.8) | 32 (43.2) | 38 (30.2) | 11 (40.7) | 809 | |

| 2 | 108 (6.9) | 8 (10.0) | 5 (6.5) | 7 (5.6) | 5 (18.5) | 133 | |

| Primary Site | Ovary | 1300 (83.0) | 73 (91.3) | 63 (85.1) | 109 (86.5) | 18 (66.7) | 1563 |

| Fallopian tube | 30 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.7) | 36 | |

| Primary peritoneum | 236 (15.1) | 7 (8.8) | 8 (10.8) | 15 (11.9) | 8 (29.6) | 274 | |

| Histology | Papillaiy serous | 1342 (85.7) | 67 (83.8) | 58 (78.4) | 96 (76.2) | 22 (81.5) | 1585 |

| Endometrioid | 4S (3.1) | 4 (5.0) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 59 | |

| Clear cell | 40 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.4) | 7 (5.6) | 3 (11.1) | 55 | |

| Mucinous | 15 (1.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | l (3.7) | 19 | |

| Adenocarcinoma, not specified | 20 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 24 | |

| Transitional cell | 10 (0.6) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 16 | |

| Mixed adenocarcinoma | 64 (4.1) | 5 (6.3) | 9 (12.2) | 6 (4.8) | 1 (3.7) | 85 | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 20 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 21 | |

| Other | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 | |

| Stage, Residual size | III-optimal | 537 (34.3) | 22 (27.5) | 25 (33.5) | 46 (36.5) | 10 (37.0) | 640 |

| III-subofstimal | 629 (40.2) | 38 (47.5) | 24 (32.4) | 51 (40.5) | 10 (37.0) | 752 | |

| IV | 400 (25.5) | 20 (25.0) | 25 (33.5) | 29 (23.0) | 7 (25.9) | 481 | |

| BMI | <25 | 703 (44.9) | 22 (27.5) | 34 (459) | 100 (79.4) | 8 (29.6) | 867 |

| 25–29.9 | 424 (27.1) | 18 (225) | 22 (29.7) | 21 (16.7) | 7 (25.9) | 492 | |

| 230 | 439 (28.0) | 40 (50.0) | 18 (24.3) | 5 (4.0) | 12 (44.4) | 514 | |

| Total | 1566 | 80 | 74 | 126 | 27 | 1873 | |

The treatment regimens were carboplatin, paclitaxel and placebo for cycles 1–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTP->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1–6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1–6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by bevacizumab for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Bevacizumab). Twenty-seven patients were listed in the other category and this group comprised seven American Indian/Alaskan native patients and twenty patients who did not specify a racial or ethnic group. NH=Non-Hispanic.

Table 2.

Pattern characteristics by age group (on-line only).

| Patient characteristics | Age Croup (years) |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 |

60–69 |

≥70 |

|||

| n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Study Regimen | CTP- > Placebo | 307 (32.8) | 214 (35.1) | 104 (31.7) | 625 |

| CTB- > Placebo | 307 (32.8) | 201 (33.0) | 117 (35.7) | 625 | |

| CIB- > Bevacmrnub | 321 (34.3) | 195 (32.0) | 107 (32.6) | 623 | |

| Performance status | 0 | 504 (53.9) | 296 (48.5) | 131 (39.9) | 931 |

| 1 | 381 (407) | 263 (43.1) | 165 (50.3) | 809 | |

| 2 | 50 (5.3) | 51 (8.4) | 32 (9.8) | 133 | |

| Primary site | Ovary | 835 (89.3) | 477 (78.2) | 251 (76.5) | 1563 |

| Fallopian tube | 16 (1.7) | 15 (2.5) | 5 (1.5) | 36 | |

| Primary peritoneum | 84 (9.0) | 118 (19.3) | 72 (22.0) | 274 | |

| Histologic type | Papillary serous | 760 (81.3) | 528 (86.6) | 297 (90.5) | 1585 |

| Endometrioid | 35 (3.7) | 17 (2.8) | 7 (2.1) | 59 | |

| Clear cell | 37 (4.0) | 15 (2.5) | 3 (0.9) | 55 | |

| Mucinous | 12 (1.3) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 19 | |

| Transitional | 16 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 | |

| Other | 75 (8.0) | 44 (7.2) | 20 (6.1) | 139 | |

| Total | 935 | 610 | 328 | 1873 | |

The treatment regimens were carboplatin, paclitaxel and placebo for cycles 1–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTP->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1-6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1–6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by bevacizumab for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Bevacizumab).

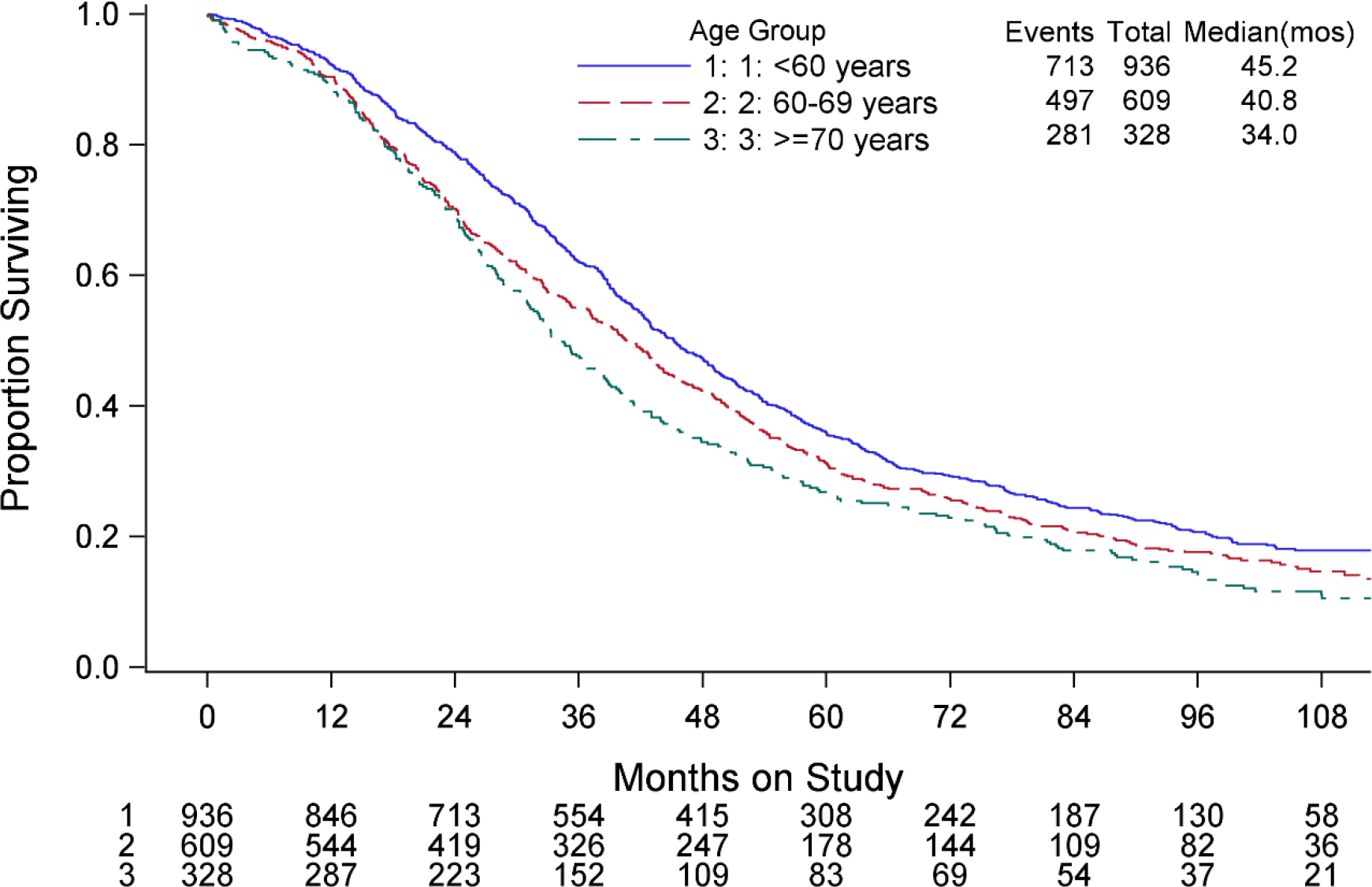

OS curves by age group show increased risk of death with increasing age (p<0.001; Figure 2, Table 3). The hazard ratios (HR) for OS adjusted for stage and treatment showed that women who were 60 to 69 years of age had an 18% increase risk of death (HR=1.18; 95% CI: 1.05–1.32) and women age 70 or older had a 34% increase risk of death when compared to women under 60 (HR=1.34; 95% CI 1.16–1.54). Grade 3 or greater toxicities also varied by age with patient’s age 70 years or older having more cardiac, musculoskeletal, metabolic, neurologic, and hematologic toxicities than other age groups (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Overall survival by age group.

Table 3.

Kaplan-Meier overall Survival estimates.

| Events / At-risk | Median (95% Cl), montlis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age Group | <60 yews | 713 / 936 | 452 (42.5–48.5) |

| 60–69 years | 497 / 609 | 408 (37.1–43.7) | |

| ≥70 yews | 281 / 328 | 34.0(31.0–38.4) | |

| Race & Ethnicity | Asian/PI | 89 / 126 | 528(44.4–64.8) |

| Hispanic | 52/74 | 412(32.4–51.3) | |

| NH-Black | 69/80 | 37.1 (28.1–472) | |

| NH-White | 1262 / 1566 | 41.0 (39.0–43.0) | |

| Other/NOS | 19 / 27 | 30.9(23.1–80.4) | |

| Asian/Pi by country of origin | Japan | 31 / 44 | 559(43.0–83.0) |

| Korea | 14 / 29 | 91.7(44.3 – undefined 1 | |

| US. | 44 / 53 | 432 (38.9–56.0) | |

PI=Pacific Islander, NH=Non-Hispanic, NOS=Not specified or unknown Twenty-seven patients were listed in NOS category and this group comprised seven American Indian/Alaskan native patients and twenty patients who did not specify a racial or ethnic group.

Table 4.

Severe patient taxidties (grade ≥ 3) by age (on-line only).

| System Organ Class | <60 years (n = 935) | 60–69 years (n = 610) | 170 years (n=32S) | Pearson Chi-squared P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Auditory Eat | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.51* |

| Allergy/Immunology | 39 (4.2) | 17 (2.3) | 6 (1.3) | 0.08 |

| Coagulation | 8(0.9) | 7(1.1) | 6(13) | 035 |

| Constitutional Symptoms | 96 (10.3) | 75 (12.3) | 41 (12.5) | 036 |

| Cardiac | 46 (4.9) | 56 (92) | 46 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| Derma tolcrgy/Skin | 29(3.1) | 17(23) | 3(05) | 0.10 |

| Death | 7 (0.7) | 11 (1.5) | 5 (1.5) | 0.16 |

| Endocrine | 7 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.3) | 0.36* |

| Gastrointestinal | 154 (16.5) | 118 (19.3) | 59 (18.3) | 0.35 |

| Renal/Genitourinary | 14 (1.5) | 10 (1.3) | 5 (1.5) | 0.57 |

| Hemorrhage/Bleeding | 15 (1.6) | 11 (1.3) | 4 (1.2) | 0.79 |

| Hematologic/Toxicity | 810 (86.6) | 554 (90.8) | 298 (90.9) | 0.016 |

| Hepatobiliaiy/Pancreas | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0.86* |

| Infection | 111 (11.5) | 84 (13.8) | 50 (15.2) | 0.25 |

| Lymphatics | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 0.33* |

| Secondary Malignancy | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.3) | 0.67* |

| Musculoskeletal/Soft Tissue | 18 (1.5) | 13 (2.1) | 22 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic/Laboratory | 119 (12.7) | 98 (13.1) | 66 (20.1) | 0.004 |

| Neurology | 70 (75) | 67 (11.0) | 73 (22.3) | <0.001 |

| Ocular/Visual | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (1.2) | 0.07* |

| Pulmonary/Upper Respiratory | 41 (4.4) | 31 (5.1) | 25 (7.6) | 0.07 |

| Pain | 141 (15.1) | 81 (13.3) | 35 (10.7) | 0.13 |

| Sexual Reproductive Function | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.3) | 1.00* |

| Vascular | 46 (4.5) | 37 (6.1) | 25 (7.6) | 0.18 |

Adverse events graded with CTCAE version 3.

Denotes p-vaiue bom Fisher’s exact test.

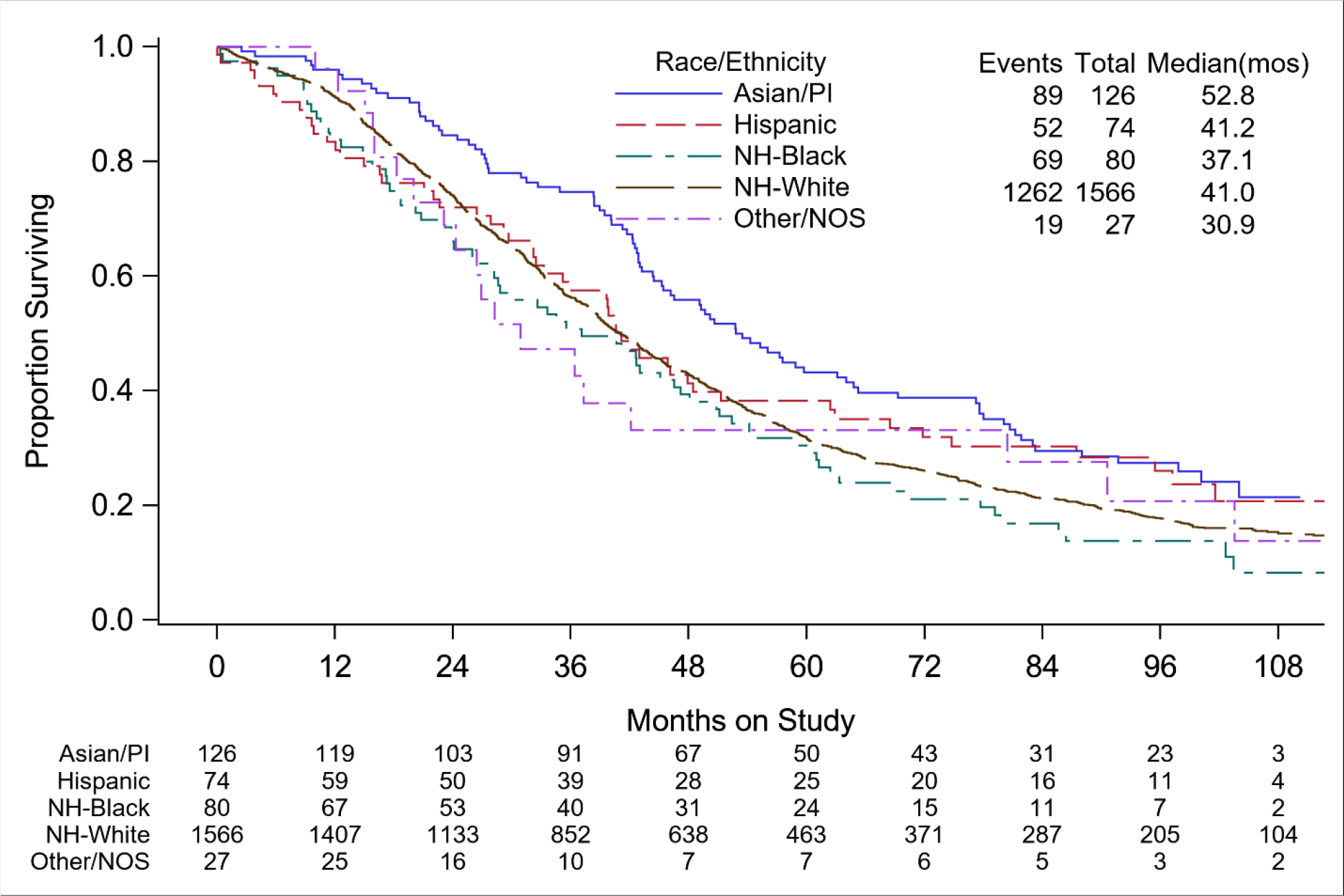

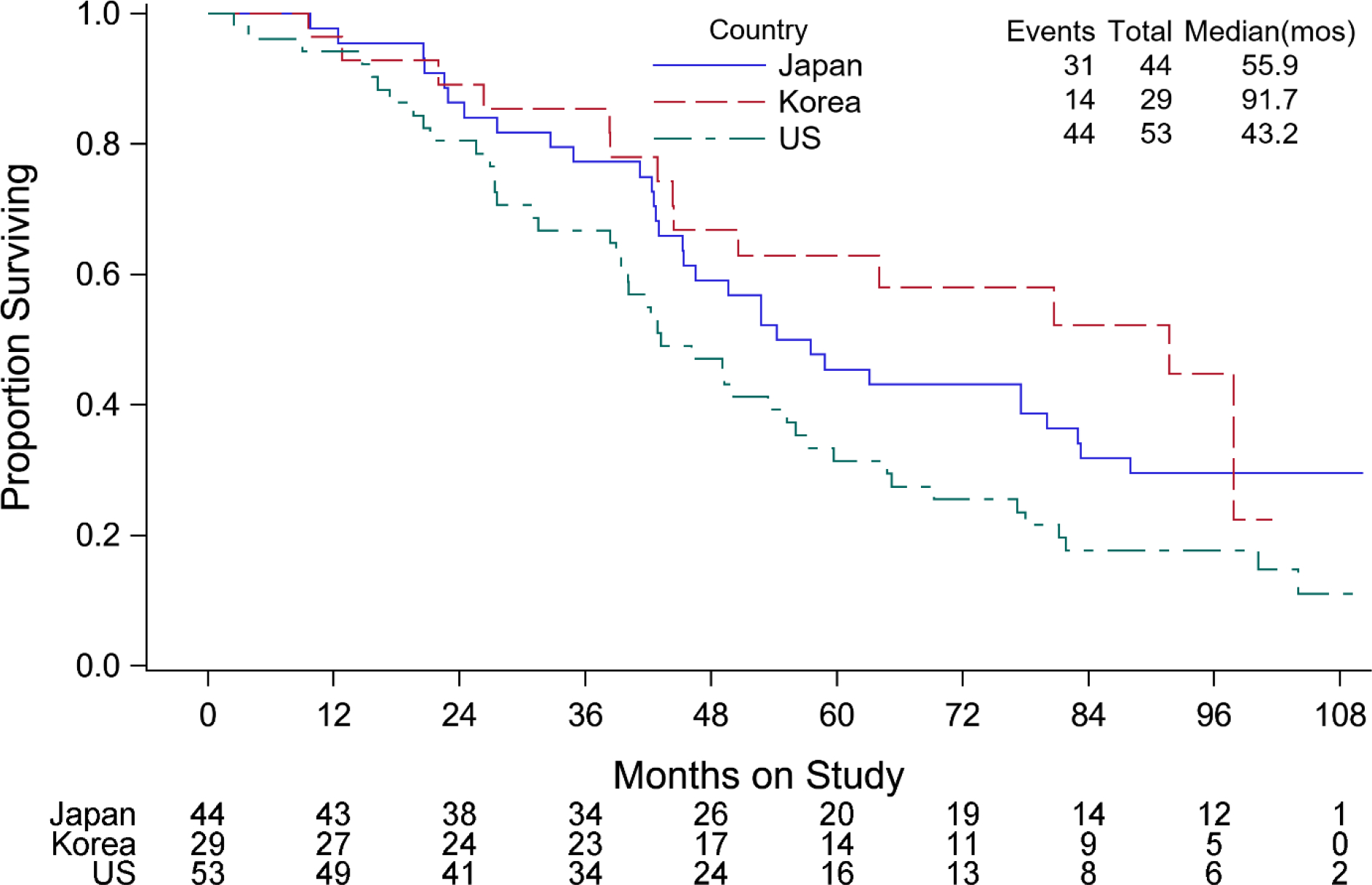

OS curves show a significant difference in OS among the race/ethnicity subgroups (p=0.017; Figure 3, Table 3). In particular, the HR for OS adjusted for stage and treatment show that women of Asian/PI ancestry had a 27% decrease risk of death as compared to non-Hispanic Whites (HR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.59–0.90). When toxicity was examined by race/ethnicity, women of Asian descent had more hematologic grade 3 or greater adverse events (Table 5). Interestingly, women of Asian descent were more likely to have a normal body mass index (BMI) than other racial groups (Table 1). Although not statistically significant, native Korean women had a median OS of 91.7 months compared to 55.9 months in Japanese women and 43.2 months for Asian women from the US (Figure 4, Table 3).

Figure 3. Overall survival by race and ethnicity.

PI=Pacific Islander, NH=Non-Hispanic, NOS=Not specified or unknown

Table 5.

Severe patient toxicities (grade ≥ 3) by race/ethnicity (on-line only).

| System Organ Class | NH-White (n = 1566) | NH-Black (n = 80) | Hispanic (n = 74) | Asian/PI (n = 126) | Other (n = 27) | Pearson Chi-squared P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Auditory/Ear | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.51* |

| Allergy/Immunology | 53 (3.4) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (3.2) | 1 (3.7) | 0.90* |

| Coagulation | 21 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.66* |

| Constitutional Symptoms | 183 (11.7) | 9 (11.3) | 10 (13.5) | 8 (6.3) | 2 (7.4) | 0.40 |

| Cardiac | 125 (8.0) | 6 (7.5) | 6 (8.1) | 8 (6.3) | 3 (11.1) | 0.93 |

| Dermatology/Skin | 40 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (3.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0.44* |

| Death | 21 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.39* |

| Endocrine | 10 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00* |

| Gastrointestinal | 286 (18.3) | 15 (18.8) | 9 (12.2) | 14 (11.1) | 7 (25.9) | 0.14 |

| Renal/Cenitourinary | 27 (1.7) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.67* |

| H emorr hage/Bleeding | 29 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.72* |

| Hematologic Toxicity | 1394 (89.0) | 66 (82.5) | 58 (78.4) | 121 (96.0) | 23 (85.2) | 0.001 |

| Hepatobiliary/Pancreas | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.7) | 0.025* |

| Infection | 213 (13.6) | 9 (11.3) | 6 (8.1) | 12 (9.5) | 5 (18.5) | 0.36 |

| Lymphatics | 9(0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (05) | 0 (0.0) | 0.83* |

| Secondary Malignancy | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00* |

| Musculoskeletal/Soft Tissue | 42 (2.7) | 4 (5.0) | 3 (4.1) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.54* |

| Metabolic/Laboratory | 230 (14.7) | 18 (22.5) | 12 (16.2) | 17 (13.5) | 6 (22.2) | 0.29 |

| Neurology | 180 (11.5) | 5 (6.3) | 12 (16.2) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (18.5) | 0.08 |

| Ocular/Visual | 8 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.66* |

| Pulmonary/Upper Respiratory | 87 (5.6) | 5 (6.3) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.25* |

| Pain | 220 (14.0) | 9 (11.3) | 10 (13.5) | 11 (8.7) | 7 (25.9) | 0.16 |

| Sexual/Reproductive Function | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00* |

| Vascular | 99 (6.3) | 3 (3.8) | 3( 4.1) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (7.4) | 0.05* |

Adverse events graded with CTCAE version 3. NH=Non-Hispanic, PI=Pacific Islander.

Denotes p-value from Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 4.

Overall survival for Asian patients by country of origin.

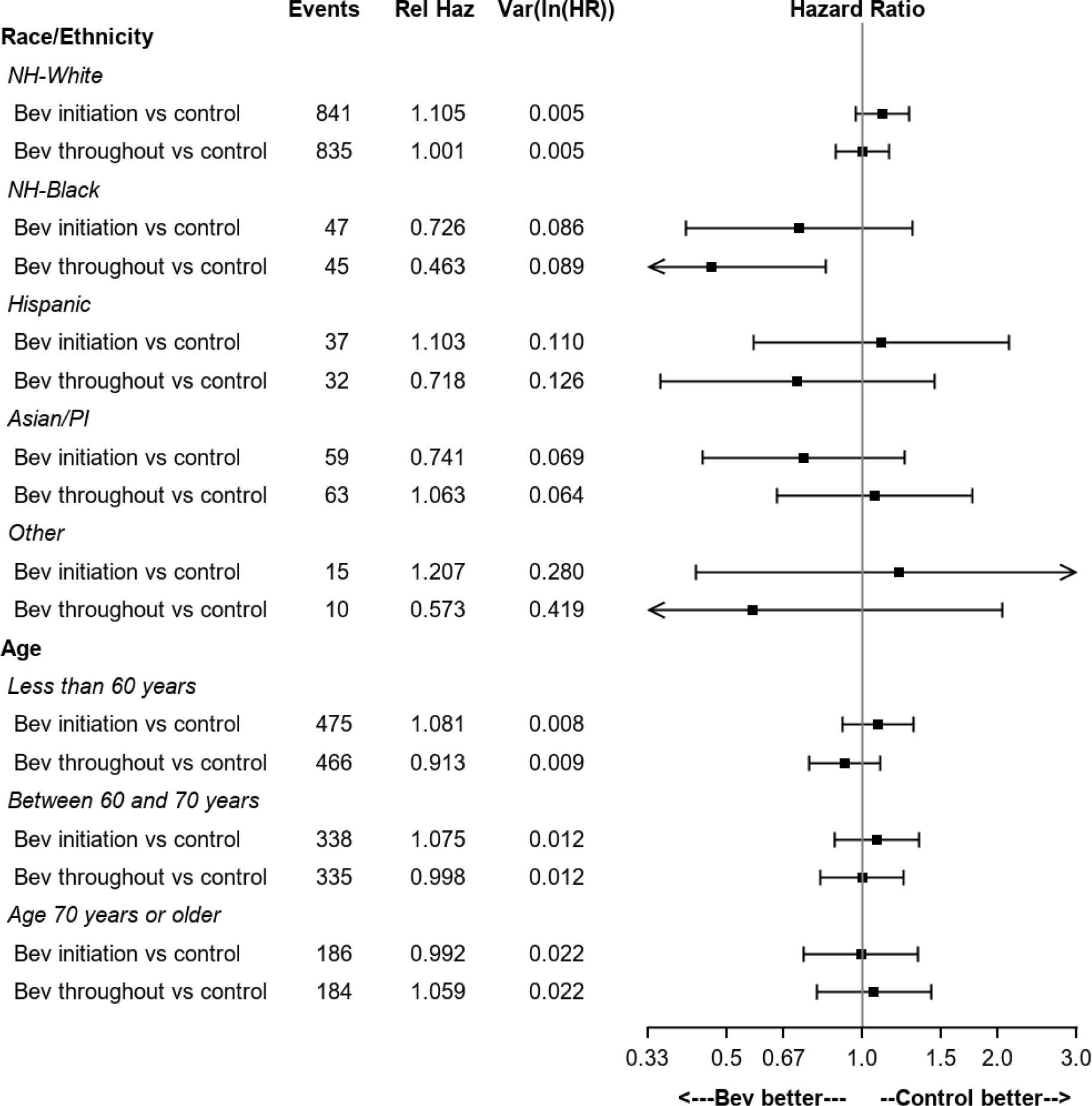

In terms of treatment effect with the addition of first-line or maintenance bevacizumab there was no difference among the three treatment arms in terms of age (p=0.73) and race/ethnicity (p=0.16) (Figure 5). However, non-Hispanic Black patients who were randomized to receive maintenance bevacizumab had a 54% decreased risk of death adjusted for stage and performance status as compared to non-Hispanic Black patients in the control group (HR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.26–0.83) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Treatment effect on overall survival by race/ethnicity and age.

The treatment regimens were carboplatin, paclitaxel and placebo for cycles 1–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTP->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1–6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by placebo for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Placebo); carboplatin, paclitaxel for cycles 1–6 and bevacizumab for cycles 2–6 followed by bevacizumab for cycles 7–22 (CTB->Bevacizumab). PI=Pacific Islander, NH=Non-Hispanic.

DISCUSSION

The goal of GOG-218 was to determine if front-line or maintenance bevacizumab impacted progression free survival (PFS) in women with surgically staged advanced ovarian cancer. The addition of upfront and maintenance bevacizumab to the standard regimen of intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel offered patients a 3.8 month increase in PFS over placebo however, there was no improvement in OS [23,27]. The goal of this sub analysis was to determine if there was a difference in outcome in women of different ethnic or racial groups or in elderly women enrolled in GOG-218.

The results of this sub-analysis showed an improvement in survival in non-Hispanic Black women who received upfront and maintenance bevacizumab. These findings can be explained by the fact that non-Hispanic Black women enrolled in GOG-218 were more likely to have suboptimal debulking after primary surgery and 25% of these women had stage IV cancer. Therefore, the extended use of bevacizumab may have been beneficial to this high risk group of patients. The final results of GOG-218 showed that patients with stage IV cancer who received upfront and maintenance bevacizumab had a median OS advantage of 42.8 vs 32.6 months (27). Therefore, patients with suboptimal residual disease after primary surgery or stage IV disease may be the best patient population to offer upfront and maintenance bevacizumab with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy for the treatment of ovarian cancer (27).

We present one of the first reports in ovarian cancer comparing native Asian women and US women of Asian ancestry to other racial groups receiving similar treatment [28]. While a statistically significant difference in OS among the different racial groups was not seen in this clinical trial, a clinically meaningful lower death rate was seen in all Asian women when compared to non-Hispanic White women. This difference is not believed to be treatment related due to the advantages of a randomized clinical trial but may have been related to the lower BMI seen in women of Asian ancestry and other factors that were not explored in this trial such as surgical aggressiveness and diet. The lower BMI seen in women of Asian ancestry may have led to the higher level of severe hematologic toxicities but also to the higher survival rates seen in this patient population since chemotherapy dosing may be more efficient in normal weight patients.

Zhang et al. studied the differences in the survival rate of patients with nine different cancers based upon race and ethnicity [29]. They used the SEER database to evaluate over 950,000 patients over a five-year period [29]. The authors showed that Black and Hispanic patients had lower cancer specific survival than Asian or White patients [29]. This study highlights the fact that more research is needed to understand all the factors that affect the cancer specific survival of minority populations with gynecologic malignancies. Other investigators have examined the outcome of ovarian cancer care in racial minorities, and they have shown that when treatment factors are equal, disparities are due to insurance status and differential access to high volume hospitals and high-volume surgeons [7–11, 19, 21]. These factors may play a larger role in OS than race or ethnicity.

Older patients with ovarian cancer face outcome disparities due to their perceived frailty and co-morbidities and they are likely to experience lower rates of cytoreductive surgery in favor of conservative treatments [30–31]. In this report, patients 70 years and older had significant cardiac, musculoskeletal, metabolic, neurologic and hematologic toxicities than younger participants. Perri et al. evaluated a retrospective cohort of 169 patients with different gynecologic malignancies who were age 79 and older [31]. Twenty-six percent of their patient population had ovarian cancer [31]. Perri et al. showed that for all patients with suboptimal treatment the age and stage adjusted HR for death was 1.76 when compared to patients who had optimal treatment [31]. In the current study, women who were over 60 had an increased risk of death compared to women under 60 despite similar treatment. Therefore, as the US population ages finding ways to ameliorate this risk factor could improve care to the growing elderly patient population.

This study is a post-hoc analysis and was not powered to evaluate the prognostic significance of ethnicity and age, therefore, this is the main limitation of this study. Another limitation is the small number of minority and elderly women enrolled in this large, randomized phase III clinical trial. Women enrolled in clinical trials are commonly treated at academic medical centers while most adult cancer patients in the US receive care in non-academic community centers and therefore most clinical trials will have limitations on the generalizability of the study findings to the broader US population [32]. In addition, the number of women enrolled from Japan and Korea was small despite the data showing intriguing outcomes. Despite these limitations this study highlights the importance of increasing the number of elderly patients and racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials so that our trials will be more representative of the patient population and when enrollment reflects the general cancer population our data will provide better personalization of cancer care.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Black women were more likely to have suboptimal debulking but a decreased risk of death with extended bevacizumab

A clinically meaningful lower death rate was seen in all Asian women when compared to non-Hispanic White women

Native Asian women had a trend towards a longer median overall survival when compared to American women of Asian ancestry

Enrolling more elderly and racial/ethnic minority patients is needed for better personalization of cancer care

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Non-Hispanic black women had a decreased risk of death with upfront and maintenance bevacizumab

Women of Asian ancestry had a decreased risk of death when compared to white women

Native Asian women had a longer median overall survival rate when compared to American women of Asian ancestry

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Daniele A. Sumner, BA for her assistance in editing the manuscript.

This study was supported by National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute grants to NRG Oncology (1 U10 CA180822) and NRG Operations (U10CA180868).

The following Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in the primary treatment studies: University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California Medical Center at Irvine-Orange Campus, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Mayo Clinic, Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Metro-Minnesota CCOP, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Abington Memorial Hospital, Rush University Medical Center, University of Kentucky, Washington University School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Women’s Cancer Center of Nevada, Indiana University Hospital/Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Seoul National University Hospital, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Duke University Medical Center, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of Chicago, University of Colorado Cancer Center – Anschutz Cancer Pavilion, University of California at Los Angeles Health System, Yale University, The Hospital of Central Connecticut, Northwestern University, Cooper Hospital University Medical Center, Women and Infants Hospital, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, University of New Mexico, University of Hawaii, Case Western Reserve University, Cancer Research for the Ozarks NCORP, Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, University of Texas – Galveston, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, University of Virginia, University of Minnesota Medical Center-Fairview, Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Stony Brook University Medical Center, Saint Vincent Hospital, Wayne State University/Karmanos Cancer Institute, University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care, Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Fletcher Allen Health Care, Gynecologic Oncology of West Michigan PLLC, Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Cincinnati, Carle Cancer Center, Michigan Cancer Research Consortium Community Clinical Oncology Program, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Scott and White Memorial Hospital, Cancer Research Consortium of West Michigan NCORP, Central Illinois CCOP, Delaware/Christiana Care CCOP, Northern New Jersey CCOP, Virginia Mason CCOP, Tacoma General Hospital, Wisconsin NCI Community Oncology Research Program, New York University Medical Center, Colorado Cancer Research Program NCORP, Saint Louis-Cape Girardeau CCOP, Aurora Women’s Pavilion of Aurora West Allis Medical Center, University of Illinois, Evanston CCOP-North Shore University Health System, Kalamazoo CCOP, Missouri Valley Cancer Consortium CCOP, William Beaumont Hospital, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Kansas City CCOP, Upstate Carolina CCOP, Dayton Clinical Oncology Program, Mainline Health CCOP, Meharry Medical College Minority Based CCOP, Heartland Cancer Research CCOP and Wichita CCOP.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conflict of Interest Statement: This research was conducted by grant support from Roche-Genentech. Roche-Genetech provided support for GOG 218 with drug supply and funds to conduct the clinical trial.

Dr. Nefertiti duPont received a GOG Young Investigator Award from Genentech. She participated on a GSK gynecologic malignancy virtual advisory board, Sanara MedTech surgical advisory board, AstraZeneca and Merck advisory boards; HCA Houston Healthcare, Northwest Chief of Staff (2020) and Immediate Past Chief of Staff (current); SGO Ethics Committee Vice Chair (current), HCA Houston Heathcare, Northwest Credentials Committee, Chair (current).

Dr. Danielle Enserro received grants or contracts from NCI/NIH – NCT00262847.

Dr. Mark Brady received grants or contracts from NCI/NIH – NCT00262847.

Dr. Premal Thaker served as an Investigator initiated trial payable to institution from Merck and GlaxoSmithKline. She also received consulting fees from Celsion, Aravive and Mana Therapeutics. She received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Merck, Dova pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Clovis, Celsion, Eisai, Immunogen and Genelux. She participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for Iovance and Novocure. She also has stock or stock options from Celsion.

Dr. Andrew Wahner Hendrickson participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for Epsila Bio, Inc. and Agenus.

Dr. Robert Burger received consulting fees from Tesaro, Genentech, Agenus, Myriad and Merck. He also received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Tesaro and Genentech. He participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from Morphotek. He has stock/stock options from Genentech when employed from 5/2020 to 11/2020 (relinquished upon resignation) and Mersana Therapeutics as an employee from 11/2020 to present, stock options only. He received other financial or non-financial interests from Genentech as an employee from 5/2020 to 11/2020 and also Mersana Therapeutics as employee from 11/2020 to present.

Dr. Bradley Monk has financial relationships from Agenus, Akeso Bio, Aravive, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Easai, Elevar, Genmab/Seattle Genetics, GOG Foundation, Gradalis, ImmunoGen, Karyopharm, Iovance, Merck, McKesson, Mersana, Novocure, Myriad, Pfizer, Puma, Roche/Genentech, Sorrento, Tesaro/GSK and VBL as consultant and or spearker/consultant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J Clin 2020; 70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havrilesky LJ, Whitehead CM, Rubatt JM, Cheek RL, Groelke J, He Q, et al. Evaluation of biomarker panels for early stage ovarian cancer detection and monitoring for disease recurrence. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 110:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke-Pearson DL. Clinical practice. Screening for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thigpen T, Brady MF, Omura GA, Creasman WT, McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, et al. Age as a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 1993; 71(2 Suppl):606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter WE, Maxwell GL, Tian C, Carlson JW, Ozols RF, Rose PG, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:3621–3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan JK, Loizzi V, Lin YG, Osann K, Brewster WR, DiSaia PJ. Stages III and IV invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma in younger versus older women: what prognostic factors are important? Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long B, Chang J, Ziogas A, Tewari KS, Anton-Culver H, Bristow RE. Impact of race, socioeconomic status, and the health care system on the treatment of advanced-stage ovarian cancer in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 212:468.e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer KC, Peterson CE, Davis FG, Hoskins K, Pauls H, Joslin CE. The influence of neighborhood socioeconomic status and race on survival from ovarian cancer: a population-based analysis of Cook County, Illinois. Ann Epidemiol 2015; 25(8):556–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristow RE, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, Chen L, Miller JP, Roland PY, et al. Disparities in ovarian cancer care quality and survival according to race and socioeconomic status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105:823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Ibeanu OA. Racial disparities in ovarian cancer surgical care: a population-based analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 121:364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrill RM, Anderson AE, Merrill JG. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of surgery for ovarian cancer in the United States. Adv Med Sci 2010; 55:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorman PG, Palmieri RT, Akushevich L, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM. Ovarian cancer risk factors in african-american and white women. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 170:598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terplan M, Schluterman N, McNamara EJ, Tracy JK, Temkin SM. Have racial disparities in ovarian cancer increased over time? An analysis of SEER data. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 125:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farley J, Risinger JI, Rose GS, Maxwell GL. Racial disparities in blacks with gynecologic cancers. Cancer 2007; 110:234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du XL, Lin CC, Johnson NJ, Altekruse S. Effects of individual-level socioeconomic factors on racial disparities in cancer treatment and survival: findings from the national longitudinal mortality study, 1979–2003. Cancer 2011; 117:3242–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan JK, Zhang M, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. Racial disparities in surgical treatment and survival of epithelial ovarian cancer in United States. J Surg Oncol 2008; 97:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aranda MA, McGory M, Sekeris E, Maggard M, Ko C, Zingmond DS. Do racial/ethnic disparities exist in the utilization of high-volume surgeons for women with ovarian cancer? Gynecol Oncol 2008; 111:166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewster WR. The complexity of race in the disparate outcome and treatment of minority patients. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 111:161–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erickson BK, Martin JY, Shah MM, Straughn JM Jr, Leath CA 3rd. Reasons for failure to deliver national comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) adherent care in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer at an NCCN cancer center. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 133:142–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire V, Herrinton L, Whittenmore AS. Race, epithelial ovarian cancer survival, and membership in a large health maintenance organization. Epidemiology 2002; 13:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins Y, Holcomb K, Chapman-Davis E, Khabele D, Farley JH. Gynecologic cancer disparities: a report from the health disparities taskforce of the society of gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 133:353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farley JH, Tian C, Rose GS, Brown CL, Birrer M, Maxwell GL. Race does not impact outcome for advanced ovarian cancer patients treated with cisplatin/paclitaxel: an analysis of gynecologic oncology group trials. Cancer 2009; 115:4210–4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2473–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J American Statistical Association 1958; 53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1972; 34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks on the one-criterion variance analysis. Journal American Statistical Association 1952; 47:907–911. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tewari KS, Burger RA, Enserro D, Norquist DM, Swisher EM, Brady MF, et al. Final overall survival of a randomized trial of bevacizumab for primary treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37:2317–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.duPont N, Brady M, Burger R, Monk B. Prognostic significance of ethnicity and age in advanced stage ovarian cancer: an analysis of GOG 218. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 130:e21–e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C, Zhang C, Wang Q, Li Z, Lin J, Wang H. Differences in Stage of Cancer at Diagnosis, Treatment and Survival by Race and Ethnicity Among Leading Cancer Types. JAMA Network Open 2020; 3(4):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hightower RD, Nguyen HN, Averette HE, Hoskins W, Harrison T, Steren A. National survey of ovarian carcinoma IV: Patterns of care and related survival for older patients. Cancer 1994; 73:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perri T, Katz T, Korach J, Beiner ME, Jakobson-Setton A, Ben-Baruch G. Treating gynecologic malignancies in elderly patients. Am J Clin Oncol 2015; 38:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parra A, Karnad AB, Thompson IM. Hispanic accrual on randomized cancer clinical trials: a call to arms. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(18):1871–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]