Abstract

Background:

There is scanty evidence regarding the magnitude of COVID-19-related psychological distress (PD) among the general population of India.

Objectives:

This study aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of PD among the general public of India during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and Methods:

We conducted a meta-analysis of 21 online surveys conducted across the Indian subcontinent and published between 2020 and 2021.

Results:

Overall estimates of PD among the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic by the random-effects model is 33.3% (95% confidence interval: 23.8%-42.8%; n = 21 studies). The level of heterogeneity was high among the included studies (I2 = 99.67%). In subgroup analysis, it was found that the survey tool and the methodological quality had a significant effect on the overall prevalence estimates. Approximately 33% of the general public reported to have PD during the COVID-19 pandemic in India, although the overall prevalence varied based on survey tools and quality of studies.

Conclusion:

As the pandemic crisis seems to be ebbing across the world, the current findings are a wake-up call to devise pragmatic strategies to curtail the burden of similar pandemics and to successfully meet the challenges ahead.

Keywords: COVID-19, India, psychological distress, the general public

INTRODUCTION

Psychological distress (PD) is an indicator for assessing the mental health of the population in epidemiological studies and as a health and psychological outcome.[1] The PD is a state of emotional turmoil and has diversified meaning as per the context. It is widely agreed that, it is a state of emotional insufficiency or emotional distress.[2] COVID-19 pandemic has severe physical, emotional, and psychological consequences which were novel to the society. With the global pandemic, these “silent” and insidious issues can go unnoticed.[3] The common response to COVID-19 is confinement to physical spaces, lack of mobility, loss of income, isolation from the family and friends, powerlessness, helplessness, and affecting the overall well-being of the individual and community during the lockdown. Uncertainty and insecurity of the future might have resulted in more symptoms of PD.[4]

As the pandemic seems to be ebbing with the impending uncertainty and the emergence of a new strain of the virus, there is a potential for yet another wave, which demands preparedness at the individual, family, and community levels.[5] A large and sufficient number of national and international studies serve a better understanding of PD during the pandemic. This pandemic period has taught the requirement of empirical data to devise the preventive mental health strategies to diminish perceived distress and augment subjective psychological well-being to manage the crisis.[6] Every individual has varying degrees of PD due to COVID 19 and the effect of the virus and related pandemics poses much uncertainties among general public.[7] This warrants immediate attention of the researchers and policy makers to identify the pandemic's aggregate burden, which is untapped. Hence, the present study is aimed to identify the empirical literature on the pooled prevalence of psychological distress among the general public of India during the COVID 19 pandemic.

METHODS

Article search strategy

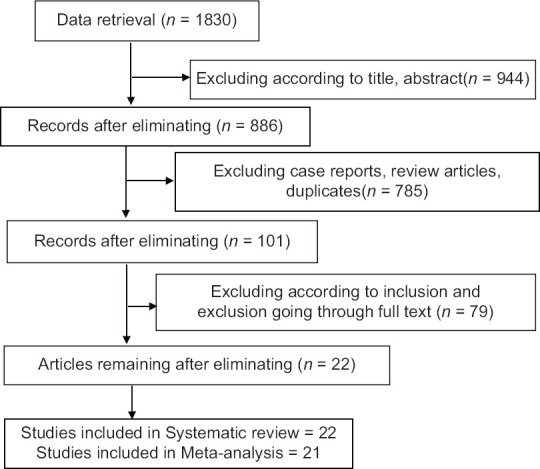

We searched, PubMed, Wiley online library, Science Direct, APA Psych Info, Proquest, and Google Scholar with the following keywords: “general public,” “COVID-19,” “psychological distress,” and “India” following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis[8] guidelines to retrieve potential studies for the review. The search was performed for articles published between 2020 and 2021 [Figure 1]. Finally, 22 studies were found suitable for systematic review in which one study did not specify the cut-off score of the outcome measure, and the same was excluded in the meta-analysis (n = 21). The detailed search strategy is described in Supplementary Material 1.

Figure 1.

Process of search and selection of studies

Eligibility criteria

Our inclusion criteria were studies conducted in India; studies reporting PD, the population included the general population. PD was operationally defined as the measurement of stress during COVID-19 based on validated standardized screening tools. Our exclusion criteria were studies conducted outside India, specific populations such as health-care personnel, police personnel, reviews, case reports, and qualitative studies. Further, studies with inadequate data and outcome measures other than PD such as anxiety and depression, and psychiatric illness were also excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extraction was carried out based on the following study characteristics: author (period of study), study setting/study design, gender, sample size/sampling method, age in years, survey tool, and the prevalence of stress. The “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data”[9] was used for the risk of bias assessment of the included studies. The total quality score was ranging from 1 to 9 in which the risk of bias was categorized as follows: high (0–3), moderate (4–6), and low (7–9) risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Open meta-analyst software was used to perform this meta-analysis. Assuming the significant inconsistency among the studies, a random-effects meta-analysis model was used and I2 statistics were calculated to measure heterogeneity among studies. The funnel plot and Egger's regression tests were used to assess potential publication.

RESULTS

Studies included in our meta-analysis are shown in Table 1.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] All 22 included studies were conducted using online cross-sectional surveys using the snowball sampling technique by distributing the Google form through Facebook, WhatsApp, or Twitter. In 16 of 22 studies, the online survey was conducted across India, while in others, it was conducted in selected states/states. The sample size of included studies varied from 159 to 2317. The number of male subjects in the included studies varied from 95 to 1160 and the female subjects varied from 56 to 1541. The age of the participants varied from 15 to 70 years. In eight studies, the stress was assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21); Impact of Event Scale-revised was used in four studies and Perceived Stress Scale was used in three studies. Other scales used to assess the PD included General Health Questionnaire (12 and 28) in two studies, The 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index In in one study, Kessler PD Scale in one study, and K10 in one study. Most of the included studies were found to have a moderate risk of bias (n = 15) and the median score was 5 (mean-5.23; standard deviation -1.2). Four studies were found to have a low risk of bias (7/9). The risk of bias assessment of the studies is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies of the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic among the general population of India

| Author/period of study | Study setting and design | Male/female | Sample size/sampling method | Age in years (mean±SD)/range | Survey tools | Stress % (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anand et al.[10] Journal submission on March 06, 2021 |

Across India/Online survey | 486/574 | 1060/snow ball | 21-65 | K6 | 53.86% (571/1060) |

| Bhowmick et al.[11] April 18-May 3, 2020 |

West Bengal/Online survey | 182/171/2 others | 355/snow ball | 18-80 | WHO-5 | 37.74% (134/355) |

| Venugopal et al.[12] April 26-May 1, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 225/228 | 453/snow ball | 24.18±14.00 | GHQ 28 | 42.16% (191/453) |

| Pandey et al.[13] March 24-April 11, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 582/805 | 1387/snow ball | 25.0±10.2 | DASS 21 | 2.4% (33/1387) |

| Gopal et al.[14] March 29- May 24, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 103/56 | 159/snow ball | 27.44±9.17 | Single item Stress scale | 30.8% (49/159) |

| Verma and Mishra et al.[15] April 4-14, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 183/173 | 345/snow ball | 18-41 | DASS 21 | 11.6% (40/345) |

| Kaurani et al.[16] April 19-May 5, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 310/317 | 627/snow ball | 20-70 | PSS | 52.31% (328/627) |

| Kaur et al.[17] May 24-June 5, 2021 |

Across India/Online survey | 525/584 | 1109/snow ball | 32.98±14.72 | DASS-21 PSQI |

9.28% (103/1109) |

| Singh and Khokhar et al.[18] Last week of April 2020 |

West Bengal/Online survey | 95/139 | 234/snow ball | 28.59±10.47 | IES-R | 28.2% (66/234) |

| Nair and Rajmohan[19] April 30-May 12, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 114/149 | 263/snow ball | 29±9.8 | Structured validated questionnaire | 39.5% (103/263) |

| Ramasubramanian et al.[20] April 13-25, 2020 |

Tamil Nadu/Online survey | 830/1541 | 2317/snow ball | 25-55 | CPDI | 23.34% (541/2317) |

| Sathe et al.[21] April 29-May 3, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 283/247 | 530/snow ball | 32.45±12.22 | K10 | 23.58% (125/530) |

| Wakode et al.[22] May 18-25, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 149/108 | 257/snow ball | 25 | PSS 10 | 84% (217/257) |

| Nathiya et al.[23] May 23-29, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 278/201 | 479/snow ball | 15-30 | DASS-21 | 37.36% (179/479) |

| Sebastian et al.[24] Not available |

29 States of India/Online survey | NM | 1257/snow ball | 29.3±9.7 | IES-6 | 53.3% (670/1257) |

| Hazarika et al.[25] April 6-22, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 167/255 | 422/snow ball | 30.5±10.9 | DASS 21 | 35.5% (149/422) |

| Grover et al.[26] April 6-24, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | NM | 894/snow-ball | 41.2±13.6 | PSS | 74.49% (666/894) |

| Varshney et al.[27] March 26-29, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 491/154/8 other | 453/snow ball | 41.82±13.85 | IES-R | 47.9% (217/453) |

| Nagarajan et al.[28] May 8-June 16, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 150/250 | 400/snow ball | 15-84 | GHQ 12 | 8.8% (35/400) |

| Tomar and Suman[29] April 28-May 8, 2020 |

Across India/Online survey | 1160/1085 | 2245/snow ball | 32.4±11.4 | DASS 21 ISI |

21.60% (485/2245) |

| Wani et al.[30] May 2020 |

Kashmir/Online study | 138/149 | 287/snow ball | 27.35±78.12 | DASS 21 | 10.45% (30/287) |

| Reddy et al.[31] April 1-May 12, 2020 |

11 States of India/Online survey | 477/416 | 891/respondent-driven | 16-60 | DASS 21 | 10% (93/891) |

SD: Standard deviation, NM: Not mentioned, K6: The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (6 item; Cut off -3), K10: The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (10 item; Cut off - 25) WHO-5: The 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (Cut off -12), Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (Cut off: - Depression ≥13, Anxiety ≥09, Stress ≥19), PSS: Perceived Stress Scale (Cut off ≥14), IES-R: Impact of event scale-revised (Cut off ≥24), GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire (cutoff - 2/3; Cut off - 20.55), ISI: Insomnia Severity Index (Cut off ≥15), GHQ-28: General Health Questionnaire (Cutoff ≥23), CPDI: Peri-traumatic distress index (Cutoff ≥28), DASS 21: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21

Table 2.

Quality Assessment Criteria -Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies

| Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Score | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anand V et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Low risk of bias |

| Bhowmick S et.al | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Venugopal V C et.al | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Pandey D. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Gopal A. et.al | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Verma S. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Kaurani P et.al | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Kaur T. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Low risk of bias |

| Singh PS et al | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | High risk of bias |

| Nair et al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Ramasubramaian V. et al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Sathe, et al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Wakode N. et al | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Nathiya D. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Low risk of bias |

| Sebastian et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Hazarika M et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Low risk of bias |

| Grover S et al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Varshney M. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Nagarajan A. et.al | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Tomar S B. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

| Wani FA et.al | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | High risk of bias |

| Reddy V. et.al | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Moderate risk of bias |

Q1 - Sample frame to address the target population; Q2 – Sampled in an appropriate way; Q3 - Sample size adequacy; Q4 - Study subjects and the setting described in detail; Q5 - Data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample; Q6 - Valid methods used for the identification of the condition; Q7 - Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants; Q8 – Appropriate statistical analysis; Q9 - Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was it managed appropriately? (1 - Yes; 0 – No)

Prevalence of psychological distress

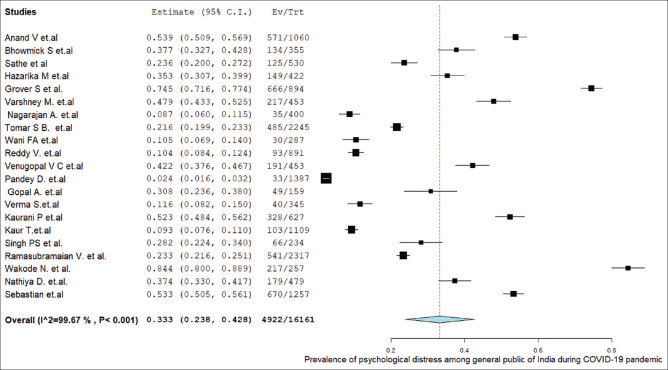

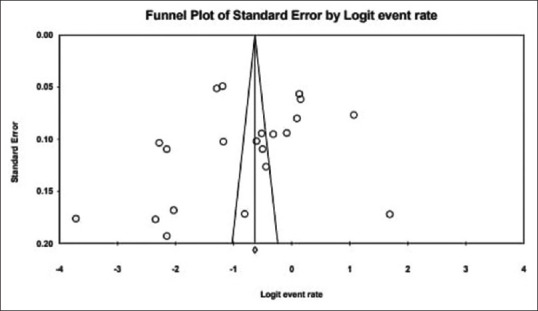

The overall estimates of PD among the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic by the random-effects model are 33.3% [95% confidence interval (CI): 23.8%–42.8%; n = 21 studies, Figure 2]. There was a significant heterogeneity on the outcome measure (I2 = 99.67%, Q = 6073.155, P < 0.001, Tau Squared = 0.049). Nonsignificant eggers test value (P = 0.34) and a reasonable symmetry of the funnel plot did not reveal any source of publication bias [Figure 3]. In sensitivity analyses, no significant effect of any particular study was found on the overall pooled estimates in which the values ranged between 30.7% (21.6%–39.8%) and 34.5% (24.6%–44.4%).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of psychological distress among general population of India during COVID-19 pandemic

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of psychological distress among general public

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis was performed based on the screening instrument tool and risk of bias assessment [Table 3]. The pooled prevalence of PD was significantly lower based on DASS-21 measurements as compared to those with studies other than DASS-21 scales (15.0%; 95% CI: 09.8%–20.1% vs. 43.0%; 95% CI: 31.2%–57.6%). In terms of methodological quality, studies with moderate risk of bias showed higher prevalence (32.3%; score-3–6) as compared to those with low risk of bias (19.1%; score >7/9).

Table 3.

The prevalence of psychological distress using random effect model by subgroup analyses

| Subgroup | Category | Number of studies | Events/N | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | χ2 (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| I2 | t | ||||||

| Screening instrument | DASS-21 | 8 | 761/7165 | 15.0% (09.8% - 20.1%) | 98.56 | 0.005 | 1182. 2 |

| Others | 13 | 3877/9025 | 43.0% (31.2% - 57.6%) | 99.48 | 0.054 | <.0001 | |

| Risk of bias (score 0-9) | Low risk (7-9) | 04 | 1002/3070 | 19.1% (14.4%-23.8%) | 98.65 | 0.014 | |

| Moderate Risk (4-6) | 15 | 3824/12570 | 32.3% (21.4%-43.1%) | 99.69 | 0.045 | 29.65 | |

| High risk (0-3) | 02 | 96/521 | 19.2% (18.0%-36.6%) | 96.22 | 0.015 | <.0001 | |

DASS 21: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21, CI: Confidence interval

DISCUSSION

The present meta-analysis is a pioneer study that elucidates the aggregate estimates of COVID-19-related PD based on the observational studies conducted among the general population of India. Our findings suggest that approximately 33% of the general public reported having PD during the COVID-19 pandemic in India.

There are certain caveats to generalize our findings. The results are purely based on online surveys conducted across the various parts of the country. To address the imposed restrictions of COVID-19, the majority of studies distributed questionnaires to an unknown broader audience posing some serious methodological limitations in the form of sampling bias and respondent bias.[32] There was a significant inconsistency among the included studies as the level of heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99.67%). This was evident in the subgroup analysis in which the survey tool and the methodological quality significantly affected the pooled prevalence. The recent meta-analyses reported relatively similar rates of PD (26%–37.3%) in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic globally.[33,34]

The psychological impact of the pandemic is largely influenced by certain factors such as onset and burden according to nations, availability of pandemic preparedness. This might be the reason for the wide variation in the average prevalence of COVID-19-related PD in the existing literature.[35,36] It is worth noting that our pooled prevalence is based on the representative number of studies (n = 21) as compared to the similar meta-analyses where the findings are reported based on a meager number of studies (n = 6). We have not included studies without a standard survey tool or cutoff scores reflecting the scientific worth of the magnitude of the outcome measure from an Indian general public perspective. Moreover, there was no significant effect of any particular study on the overall pooled estimates in our sensitivity analyses in which the values ranged from 30.7% to 34.5%. However, considering the methodological limitations, the current findings should be interpreted accordingly.

The pandemic crisis seems to be ebbing and almost all parts of the world are returning from their new normal to a normal rhythm. This wake-up call makes the governments around the world devise national strategies to curtail its spread and must re-engineer the way they operate to successfully meet the challenges ahead. There is a need for regular interaction and emotional support from friends, family, partners, caregivers, community, and social media to minimize psychological stress.[37] Further it is the requirement for a preventive mental strategy on maximizing positive mental health, diminishing perceived distress, and augmenting subjective psychological well-being to manage the crisis. It is the optimal time to design the targeted approach through the online resilience initiatives to reduce PD on a large scale with low cost in time of crisis.[38]

Strength and limitations

The major uniqueness of this study is its novelty of a meta-analysis based on a representative number of studies reflecting the magnitude of the COVID-19 related PD from an Indian general public perspective. Most of the included studies were found to have a moderate risk of bias and the separate analysis-based screening tools further add the scientific worth of the evidence. Despite the strengths, there are certain limitations to our findings. The outcome measures are based on web-based surveys in which the sample might be contaminated by respondent bias. The level of heterogeneity of the included was high and pooled estimates varied as per survey tools quality of studies.

CONCLUSION

Approximately 33% of the general public reported having PD during the COVID-19 pandemic in India, although overall prevalence varied based on survey tools and quality of studies. As the pandemic crisis seems to be ebbing across the world, the current findings are a wake-up call to devise pragmatic strategies to curtail the burden of similar pandemics and to successfully meet the challenges ahead.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Elezebeth Mathews is supported by a Clinical and Public Health Early Career Fellowship (grant number IA/CPHE/17/1/503345) from the DBT India Alliance/Wellcome Trust-Department of Biotechnology, India Alliance (2018–2023).

Supplementary Material 1

PubMed (Search hits-46)

Filters: Journal Article, English, from 2020/1/1-2021/10/31

((“human s”[All Fields] OR “humans”[MeSH Terms] OR “humans”[All Fields] OR “human”[All Fields]) AND (“covid 19”[All Fields] OR “covid 19”[MeSH Terms] OR “covid 19 vaccines”[All Fields] OR “covid 19 vaccines”[MeSH Terms] OR “covid 19 serotherapy”[All Fields] OR “covid 19 serotherapy”[Supplementary Concept] OR “covid 19 nucleic acid testing”[All Fields] OR “covid 19 nucleic acid testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “covid 19 serological testing”[All Fields] OR “covid 19 serological testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “covid 19 testing”[All Fields] OR “covid 19 testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “sars cov 2”[All Fields] OR “sars cov 2”[MeSH Terms] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[All Fields] OR “ncov”[All Fields] OR “2019 ncov”[All Fields] OR ((“coronavirus”[MeSH Terms] OR “coronavirus”[All Fields] OR “cov”[All Fields]) AND 2019/11/01:3000/12/31[Date - Publication])) AND (“india”[MeSH Terms] OR “India”[All Fields] OR “india s”[All Fields] OR “indias”[All Fields]) AND (“psychological distress”[MeSH Terms] OR (“psychological”[All Fields] AND “distress”[All Fields]) OR “psychological distress”[All Fields])) AND ((journalarticle[Filter]) AND (2020/1/1:2021/10/31[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]))

2.Wiley Online Library (Search hits = 141)

Topic: Covid 19 psychological distress Indian population” anywhere and “Psychological distress OR stress OR anxiety OR depression OR insomnia OR PTSD” anywhere and “India” anywhere

Refined by: Journal Article, from 2020/1/1-2021/10/31

3. Science Direct (Search hits = 175)

Topic: Humans, COVID-19, India, Psychological Distress

Refined by: Journal Article, from 2020/1/1-2021/10/31

4.APA Psych Info (Search hits = 10)

Any Field: humans OR Any Field: general population AND Any Field: psychological distress AND Any Field: covid-19 AND Any Field: India AND Year: 2020 To 2021

5. Proquest (search hits = 849)

Humans, COVID-19, India, Psychological Distress

Refined by: Journal Article, from 2020/1/1-2021/10/31

5. Google Scholar (Search hits- 609) Publication date from 2020/01/01 to 2021/10/31 Relevant Journals & Search:- Asian Journal of Psychiatry (9), Indian Journal of Psychiatry (272), Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry (165), Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine (15), Journal of Mental Health and Human Behavior (16), Annals of Indian Psychiatry (61), Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care (7), International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health (64)

Search terms used: Humans, COVID-19, India, Psychological Distress

REFERENCES

- 1.Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu Prévost D. Mental Illnesses Understanding, Predict Control. London: IntechOpen; 2012. Epidemiology of psychological distress. [Doi: 10.5772/30872] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridner SH. Psychological distress: Concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:536–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan KS, Mamun MA, Griffiths MD, Ullah I. The mental health impact of the COVID 19 pandemic across different cohorts. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;18:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020;113:531–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar A, Chakrabarti AK, Dutta S. Covid-19 infection in India: A comparative analysis of the second wave with the first wave. Pathogens. 2021;10:1222. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das S. Mental health and psychosocial aspects of COVID-19 in India: The challenges and responses. J Health Manag. 2020;22:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golechha M. COVID-19, India, lockdown and psychosocial challenges: What next? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:830–2. doi: 10.1177/0020764020935922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–53. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand V, Verma L, Aggarwal A, Nanjundappa P, Rai H. COVID-19 and psychological distress: Lessons for India. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhowmick S, Parolia S, Jana S, Kundu D, Choudhury D, Das N, et al. A study on the anxiety level and stress during Covid19 lockdown among the general population of West Bengal, India – A must know for primary care physicians. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:978–84. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1385_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venugopal VC, Mohan A, Chennabasappa LK. Status of mental health and its associated factors among the general populace of India during COVID 19 pandemic. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;12:e12412. doi: 10.1111/appy.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey D, Bansal S, Goyal S, Garg A, Sethi N, Pothiyill DI, et al. Psychological impact of mass quarantine on population during pandemics – The COVID-19 Lock-Down (COLD) study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopal A, Sharma AJ, Subramanyam MA. Dynamics of psychological responses to COVID-19 in India: A longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma S, Mishra A. Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:756–62. doi: 10.1177/0020764020934508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaurani P, Batra K, Hooja HR. Psychological impact of covid 19 lockdown (phase 2) among Indian general population: A cross sectional survey. Int J Sci Res. 2020;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur T, Ranjan P, Chakrawarty A, Kasi K, Berry P, Suryansh S, et al. Association of sociodemographic parameters with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, psychological trauma, mental well-being, and resilience during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey from India. Cureus. 2021;13:e16420. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SP, Khokhar A. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in general population in India during COVID-19 pandemic home quarantine. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2021;33:154–6. doi: 10.1177/1010539520968455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair DR, Rajmohan V, Raghuram TM. Impact of COVID 19 lockdown on lifestyle and psychosocial stress – An online survey. Kerala J Psychiatry. 2020;33:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramasubramanian V, Mohandoss AA, Rajendhiran G, Pandian PR, Ramasubramanian C. Statewide survey of psychological distress among people of Tamil Nadu in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42:368–73. doi: 10.1177/0253717620935581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sathe HS, Mishra KK, Saraf AS, John S. A cross-sectional study of psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 in the general population of India during lockdown. Ann Indian Psychiatry. 2020;4:181–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakode N, Wakode S, Santoshi J. Perceived stress and generalized anxiety in the Indian population due to lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. F. 1000;es 2020;9:1233. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.26371.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathiya D, Singh P, Suman S, Raj P, Tomar BS. Mental health problems and impact on youth minds during the COVID-19 outbreak: Cross-sectional (RED-COVID) survey. Soc Health Behav. 2020;3:83–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sebastian J, Anand A, Vakkalaganti Rajesh R, Lucca JM, Joseph R. Impact of covid 19 pandemic on psychological responses of the general population in India: A nationwide survey. Int J Pharm Res. 2020;12:2349–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazarika M, Das S, Bhandari SS, Sharma P. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated risk factors during the initial stage among the general population in India. Open J Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2021;12:31–5. doi: 10.5958/2394-2061.2021.00009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grover S, Sahoo S, Mehra A, Avasthi A, Tripathi A, Subramanyan A, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdown: An online survey from India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:354–62. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_427_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, Sarin SK. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: An online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagarajan A, Malhotra P, Chauhan R, Swain S. Psychological impact of COVID 19 on the general population of India: A cross sectional study. J Community Health Manag. 2021;8:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomar BS, Raj P, Suman S, Singh P, Nathiya D. Mental health and quality of life during covid 19 pandemic in Indian population. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020;12:74–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wani FA, Jan R, Ahmad M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of general population in Kashmir Valley, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2020;8:4011–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy V, Karri SR, Jezreel T, Afeen S, Khairkar P. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 lockdown on mental wellbeing among 11 states of India: a Markov modeling approach. J Psychiatry Psychiatr Disord. 2020;4:158–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrade C. The limitations of online surveys. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42:575–6. doi: 10.1177/0253717620957496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Necho M, Tsehay M, Birkie M, Biset G, Tadesse E. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67:892–906. doi: 10.1177/00207640211003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh RK, Bajpai R, Kaswan P. COVID-19 pandemic and psychological wellbeing among health care workers and general population: A systematic-review and meta-analysis of the current evidence from India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:100737. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kar SK, Ransing R, Arafat SM, Menon V. Second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in India: Barriers to effective governmental response. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100915. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]