Abstract

Introduction

The phase 3 APOLLO study demonstrated significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) and clinical responses with daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-Pd) versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone (Pd) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). On the basis of these results and those from the phase 1b EQUULEUS trial, D-Pd was approved in this patient population. In the absence of head-to-head data comparing D-Pd with further standard of care (SOC) therapies, indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) can provide important information to help optimize treatment selection. The objective of this study was to indirectly compare PFS improvement with D-Pd versus daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (D-Vd) and D-Pd versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients with RRMM.

Methods

Patient-level data were from APOLLO, EQUULEUS, and CASTOR. Three methods of adjusting imbalances in baseline characteristics including stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting (sIPTW), cardinality matching (CM), and propensity score matching (PSM) were initially considered. CM offers mathematically guaranteed largest matched sample meeting pre-specified maximum standardized mean difference criteria for matching covariates. sIPTW and PSM were based on propensity scores derived from logistic regression. Feasibility assessment of the PSM method returned too low effective sample size to support a meaningful comparison. CM was chosen as the base case and sIPTW as a sensitivity analysis.

Results

After harmonized eligibility criteria were applied, 253, 104, and 122 patients from the D-Pd, D-Vd, and Vd cohorts, respectively, were included in the ITC analyses. Some imbalances in baseline characteristics were identified between D-Pd and D-Vd/Vd cohorts that remained after adjustment. PFS hazard ratios showed significant improvement for D-Pd over D-Vd and Vd for CM and sIPTW analyses.

Conclusions

Results showed consistent PFS benefit for D-Pd versus D-Vd and Vd regardless of the adjustment technique used. These findings support the use of D-Pd versus D-Vd or Vd in patients with difficult-to-treat RRMM.

Trial Registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-022-02226-x.

Keywords: Daratumumab, Indirect treatment comparison, Multiple myeloma

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The goal of therapy in multiple myeloma is to prevent or delay relapse to extend life expectancy for as long as possible with acceptable toxicity and maintenance of quality of life. Daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-Pd) has demonstrated improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone (Pd) alone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) exposed to both proteasome inhibitor (PI) and immunomodulatory drug (IMiD). |

| The objective of this indirect treatment comparison (ITC) was to use combined data from the APOLLO, EQUULEUS, and CASTOR trials to compare improvement in PFS with D-Pd versus daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (D-Vd), and bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients with RRMM who had prior PI and IMiD exposure. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| While some imbalances in patient baseline characteristics remained between treatment cohorts, this ITC with different statistical methods demonstrates a PFS benefit for D-Pd compared with D-Vd and Vd. |

| The results of this study provide support in favor of using D-Pd versus other treatments that are part of standard of care such as D-Vd and Vd in a population of patients with difficult-to-treat RRMM and particularly in those patients who have been exposed to both a PI and an IMiD. |

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disorder diagnosed in approximately 160,000 people annually worldwide [1]. In patients with MM, proliferation of malignant clonal plasma cells leads to subsequent replacement of normal bone marrow with hematopoietic precursors and overproduction of monoclonal protein [2]. Characteristic hallmarks of the disease include osteolytic lesions, anemia, increased susceptibility to infections, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency or failure, and peripheral neuropathy [3].

Most patients with MM will relapse and become refractory to first line(s) of therapy, and with each subsequent line of therapy the duration of remission duration becomes shorter [4, 5]. Goals for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) are to induce durable and deep responses, and to prevent or delay relapse for as long as possible with acceptable toxicity and no loss in quality of life [4, 6].

Treatment of MM has advanced significantly over the past decade with the approval of novel agents including proteasome inhibitors (PI) such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib; immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD) such as lenalidomide and pomalidomide; monoclonal antibodies, namely daratumumab, isatuximab, and elotuzumab [7]; and other newer treatments in development including bispecific antibodies [8] and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T cell) therapies [9].

Daratumumab is an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody with multiple mechanisms of action including complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, induction of apoptosis by Fc gamma receptor-mediated crosslinking of tumor-bound monoclonal antibodies, and antibody-dependent phagocytosis [10]. Several daratumumab combination therapies are recommended for the treatment of patients with RRMM, most recently daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-Pd) [7]. Comparative effectiveness studies of D-Pd versus other standard of care (SOC) regimens are of great interest to inform clinical decision-making. In the absence of available head-to-head data, other than pomalidomide and dexamethasone (Pd), indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) can provide important information about the relative efficacy of D-Pd [11].

The objective of this study was to leverage patient-level data to indirectly compare the efficacy of D-Pd versus daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [D-Vd] and bortezomib and dexamethasone [Vd] using statistical adjustment for imbalances in patient characteristics at baseline. Both D-Vd and Vd are recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines in patients with RRMM [7] and have been utilized for several years in this patient population.

Methods

Data Sources and Eligibility Criteria

The present study used data from two phase 3 clinical trials (APOLLO, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03180736 and CASTOR, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02136134) and one phase 1b clinical trial (EQUULEUS, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01998971) that evaluated daratumumab combination treatments in patients with RRMM [12–14].

Data for the D-Pd cohort were taken from the APOLLO and EQUULEUS studies [12, 14]. APOLLO is a randomized open-label trial in patients with RRMM who were previously treated with at least one prior line of therapy including lenalidomide and a PI, and who were randomized to D-Pd (n = 151) or Pd (n = 153) [12]. Patients in the D-Pd group received daratumumab (1800 mg) subcutaneously (SC) or daratumumab (16 mg/kg) intravenously (IV) weekly in cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks in cycles 3–6, and every 4 weeks thereafter in combination with orally administered pomalidomide 4 mg daily on days 1–21 of each cycle and orally administered dexamethasone 40 mg weekly. Patients in the Pd group received pomalidomide 4 mg (starting dose) orally once daily on days 1–21 of each cycle and orally administered dexamethasone 40 mg weekly. EQUULEUS is a nonrandomized, open-label trial in patients with RRMM who were previously treated with at least one prior line of therapy; 103 patients were treated with D-Pd [14]. Patients received daratumumab 16 mg/kg IV weekly in cycles 1 and 2 and then every 2 weeks in cycles 3–6 and every 4 weeks thereafter, orally administered pomalidomide 40 mg daily on days 1–21 of each cycle, and orally administered dexamethasone 40 mg weekly.

Data for the D-Vd and Vd cohorts were taken from the CASTOR study, a randomized open-label trial conducted in patients with RRMM who were previously treated with at least one prior line of therapy. Patients were randomly assigned to D-Vd (n = 251) or Vd (n = 247) [13]. Patients in the D-Vd group received daratumumab 16 mg/kg IV weekly in cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks in cycles 3 to 6, and every 4 weeks thereafter, bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 SC on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of cycles 1–8, and dexamethasone 20 mg (oral or IV) on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12 of each cycle. Patients in the Vd group received bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 SC on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of cycles 1–8 and dexamethasone 20 mg (oral or IV) on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12 of each cycle.

No institutional board review was required for this post hoc analysis of the APOLLO, CASTOR, and EQUULEUS trials. Those trials were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the local institutional research committees and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in each trial.

Statistical Analyses

The matching and weighting were performed separately for the D-Pd versus Vd and D-Pd versus D-Vd comparisons. Weighting and matching methods were used to adjust for imbalances in patient characteristics at baseline between the study arms to mitigate bias due to potential confounding. Cardinality matching (CM), stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting (sIPTW), and propensity score matching (PSM) were initially considered. Both PSM and sIPTW rely on estimation of propensity scores for each patient [15]. The propensity score measures how probable it is that a patient is exposed to the treatment (rather than control) based on their baseline characteristics. PSM attempts to mitigate bias by pairing treatment and control patients who have similar propensity scores to produce a matched dataset of treatment and control patients with balanced baseline characteristics. sIPTW attempts to mitigate bias by reweighting patients in each treatment group to produce a weighted pseudo-population in which patient characteristics are balanced between treatment and control groups [16]. The patient’s weighting is based on their propensity score. The CM approach does not rely on propensity scores or directly paired treatment and control patients. Instead, CM uses integer programming techniques to find the largest subset of treatment and control patients which meets a pre-specified balancing criterion [17, 18]. As a result of limited overlap between the APOLLO, EQUULEUS, and CASTOR trial populations and the ability of CM to find the largest sample satisfying specified balancing criteria, it was anticipated that CM would potentially outperform PSM at both improving balance and preserving effective sample size (ESS) and provide better interpretability than sIPTW as the unit of observation is individual patients rather than weighted patients [19]. ITC feasibility assessments were conducted with CM, sIPTW, and PSM using combined data from APOLLO (D-Pd) + EQUULEUS (D-Pd) + CASTOR (D-Vd/Vd). A standardized mean difference (SMD) > 0.1 was used as the criterion for imbalance [20] in baseline characteristics between D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd. The PSM analysis utilized nearest-neighbor matching with replacement and caliper = 0.2. The CM procedure was implemented with a pre-specified maximum SMD criteria (≤ 0.1) for matching covariates. Results of the feasibility assessment post-harmonization (details below) revealed that the ESS for the PSM methodology was too low (D-Vd, ESS = 9 and Vd, ESS = 13) to support a meaningful analysis of PFS. CM was selected as the base case on the basis of its capability to retain sample size (Tables 1 and 2) with sIPTW as a sensitivity analysis [19].

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics for D-Pd and D-Vd cohorts before and after adjustment

| Unadjusted post harmonization | sIPTW | CM | PSM | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Pd N = 253 |

D-Vd N = 104 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 219 |

D-Vd ESS = 42 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 79 |

D-Vd ESS = 79 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 253 |

D-Vd ESS = 9 |

SMD | |

| Age % | ||||||||||||

| < 65 years | 45.5 | 50.0 | 0.091 | 46.0 | 46.0 | 0.001 | 40.5 | 44.3 | 0.077 | 45.5 | 32.4 | 0.270* |

| 65–74 years | 41.5 | 38.5 | 0.062 | 41.5 | 40.5 | 0.021 | 49.4 | 45.6 | 0.076 | 41.5 | 53.8 | 0.247* |

| ≥ 75 years | 13.0 | 11.5 | 0.046 | 12.5 | 13.6 | 0.031 | 10.1 | 10.1 | < 0.001 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 0.023 |

| Male, % | 53.4 | 55.8 | 0.048 | 54.4 | 54.5 | 0.002 | 57.0 | 54.4 | 0.051 | 53.4 | 56.9 | 0.072 |

| ISS stage (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 26.9 | 36.5 | NAa | 30.7 | 36.7 | NAa | 38.0 | 36.7 | NAa | 26.9 | 39.1 | NAa |

| 2 | 19.8 | 38.5 | NAa | 20.1 | 38.8 | NAa | 21.5 | 38 | NAa | 19.8 | 28.9 | NAa |

| 3 | 3.0 | 25.0 | NAa | 13.9 | 24.5 | NAa | 17.7 | 25.3 | NAa | 13.0 | 32.0 | NAa |

| Missing | 40.3 | 0 | NAa | 35.3 | 0 | NAa | 22.8 | 0 | NAa | 40.3 | 0 | NAa |

| ECOG performance status, % | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 47.0 | 42.3 | 0.095 | 46.4 | 43.5 | 0.058 | 46.8 | 44.3 | 0.051 | 47.0 | 48.6 | 0.032 |

| 1 | 45.8 | 53.8 | 0.160* | 47.2 | 53.1 | 0.117* | 46.8 | 50.6 | 0.076 | 45.8 | 47.8 | 0.040 |

| 2 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 0.144* | 6.4 | 3.5 | 0.135* | 6.3 | 5.1 | 0.055 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 0.159* |

| Cytogenetic risk, % | ||||||||||||

| High risk | 23.7 | 13.5 | 0.266* | 21.0 | 11.7 | 0.254* | 16.5 | 15.2 | 0.035 | 23.7 | 4.3 | 0.581* |

| Standard risk | 51.0 | 67.3 | 0.377* | 54.0 | 60.1 | 0.122* | 58.2 | 62.0 | 0.078 | 51.0 | 53.4 | 0.047 |

| Missingb | 25.3 | 19.2 | 0.146* | 25.0 | 28.3 | 0.074 | 25.3 | 22.8 | 0.059 | 25.3 | 42.3 | 0.365* |

| MM type (%) | ||||||||||||

| IgG | 54.9 | 49.0 | NAa | 55.0 | 57.8 | NAa | 55.7 | 53.2 | NAa | 54.9 | 73.9 | NAa |

| Non IgG | 33.6 | 51.0 | NAa | 34.3 | 42.2 | NAa | 34.2 | 46.8 | NAa | 33.6 | 26.1 | NAa |

| Missing | 11.5 | 0 | NAa | 10.7 | 0 | NAa | 10.1 | 0 | NAa | 11.5 | 0 | NAa |

| Prior lines of therapy, % | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 7.1 | 27.9 | 0.568* | 9.0 | 12.8 | 0.123* | 10.1 | 12.7 | 0.080 | 7.1 | 5.5 | 0.065 |

| 2–3 | 63.6 | 59.6 | 0.083 | 65.8 | 75.1 | 0.205* | 74.7 | 70.9 | 0.085 | 63.6 | 86.2 | 0.538* |

| ≥ 4 | 29.2 | 12.5 | 0.421* | 25.3 | 12.2 | 0.341* | 15.2 | 16.5 | 0.035 | 29.2 | 8.3 | 0.557* |

| Refractory to lenalidomide, % | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 83.4 | 47.1 | 0.824* | 77.7 | 73.4 | 0.101* | 65.8 | 62.0 | 0.079 | 83.4 | 86.6 | 0.089 |

| No/NA | 16.6 | 52.9 | NA | 22.3 | 26.6 | NA | 34.2 | 38.0 | NA | 16.6 | 13.4 | NA |

| Refractory status, % | ||||||||||||

| IMiD only | 29.6 | 51.0 | 0.445* | 36.0 | 44.8 | 0.180* | 57.0 | 60.8 | 0.077 | 19.6 | 26.5 | 0.070 |

| PI only | 6.3 | 0 | 0.367* | 4.7 | 0 | 0.315* | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.160* | 6.3 | 0 | 0.367* |

| Both IMiD + PI | 54.2 | 5.8 | 1.244* | 42.3 | 32.2 | 0.210* | 10.1 | 7.6 | 0.089 | 54.2 | 60.1 | 0.120* |

| None/NA | 9.9 | 43.3 | 0.816* | 17.0 | 23.0 | 0.151* | 31.6 | 31.6 | < 0.001 | 9.9 | 13.4 | 0.111* |

| Years since diagnosis, median (IQR) |

4.7 (2.72–7.19) |

4.5 (2.92–6.61) |

0.05 |

4.6 (2.74–7.06) |

4.7 (3.14–6.31) |

0.001 |

4.9 (2.84–7.19) |

4.9 (3.17–7.39) |

0.041 |

4.6 (2.71–7.16) |

4.4 (3.17–5.48) |

0.022 |

| Prior ASCT, % | 64.8 | 76.0 | 0.246* | 67.8 | 65.5 | 0.049 | 72.2 | 74.7 | 0.057 | 64.8 | 47.8 | 0.348* |

ASCT autologous stem cell transplant, CM cardinality matching, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, D-Vd daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ESS effective sample size, IgG immunoglobulin G, IMiD immunomodulatory drug, IQR interquartile range, ISS International Staging System, MM multiple myeloma, NA not available, PI proteasome inhibitor, PSM propensity score matching, sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, SMD standardized mean difference

aAs a result of missingness in the EQUULEUS study, the extent of imbalance for these subgroups is unknown. Results for D-Pd were based on data from the APOLLO study

bMissingness was treated as a distinct value

*SMD values > 0.1

Table 2.

Patient baseline characteristics for D-Pd and Vd cohorts before and after adjustment

| Unadjusted post harmonization | sIPTW | CM | PSM | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Pd N = 253 |

Vd N = 122 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 206 |

Vd ESS = 55 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 93 |

Vd ESS = 93 |

SMD | D-Pd ESS = 253 |

Vd ESS = 13 |

SMD | |

| Age, % | ||||||||||||

| < 65 years | 45.5 | 59.0 | 0.274* | 49.3 | 51.1 | 0.036 | 50.5 | 52.7 | 0.043 | 45.5 | 45.1 | 0.008 |

| 65– 74 years | 41.5 | 28.7 | 0.271* | 37.9 | 35.6 | 0.048 | 37.6 | 33.3 | 0.090 | 41.5 | 42.3 | 0.026 |

| ≥ 75 years | 13.0 | 12.3 | 0.023 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 0.016 | 11.8 | 14.0 | 0.064 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 0.012 |

| Male, % | 53.4 | 59.8 | 0.131* | 54.2 | 55.0 | 0.016 | 55.9 | 59.1 | 0.065 | 53.4 | 49.8 | 0.071 |

| ISS stage (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 26.9 | 45.9 | NAa | 32.5 | 40.4 | NAa | 38.7 | 46.2 | NAa | 26.9 | 30.0 | NAa |

| 2 | 19.8 | 37.7 | NAa | 20.0 | 39.0 | NAa | 24.7 | 35.5 | NAa | 19.8 | 43.5 | NAa |

| 3 | 13.0 | 16.4 | NAa | 14.1 | 20.7 | NAa | 18.3 | 18.3 | NAa | 13 | 26.5 | NAa |

| Missing | 40.3 | 0 | NAa | 33.4 | 0 | NAa | 18.3 | 0 | NAa | 40.3 | 0 | NAa |

| ECOG performance status, % | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 47.0 | 54.1 | 0.142* | 47.5 | 40.1 | 0.150* | 51.6 | 52.7 | 0.022 | 47.0 | 22.1 | 0.542* |

| 1 | 45.8 | 40.2 | 0.115* | 45.1 | 53.8 | 0.174* | 40.9 | 41.9 | 0.022 | 45.8 | 71.9 | 0.550* |

| 2 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 0.056 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 0.050 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 0.088 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 0.048 |

| Cytogenetic risk, % | ||||||||||||

| High risk | 23.7 | 17.2 | 0.162* | 22.0 | 28.0 | 0.139* | 19.4 | 17.2 | 0.056 | 23.7 | 36.0 | 0.270* |

| Standard risk | 51.0 | 52.5 | 0.029 | 50.1 | 47.0 | 0.063 | 47.3 | 50.5 | 0.065 | 51.0 | 45.5 | 0.111* |

| Missingb | 25.3 | 30.3 | 0.112* | 27.8 | 24.9 | 0.066 | 33.3 | 32.3 | 0.023 | 25.3 | 18.6 | 0.163* |

| MM type (%) | ||||||||||||

| IgG | 54.9 | 55.7 | NAa | 55.0 | 53.3 | NAa | 53.8 | 60.2 | NAa | 54.9 | 38.7 | NAa |

| Non IgG | 33.6 | 44.3 | NAa | 35.3 | 46.7 | NAa | 39.8 | 39.8 | NAa | 33.6 | 61.3 | NAa |

| Missing | 11.5 | 0 | NAa | 9.7 | 0 | NAa | 6.5 | 0 | NAa | 11.5 | 0 | NAa |

| Prior lines of therapy, % | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 7.1 | 27.0 | 0.549* | 9.6 | 13.8 | 0.132* | 10.8 | 14.0 | 0.098 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 0.059 |

| 2–3 | 63.6 | 59.0 | 0.095 | 65.7 | 72.2 | 0.140* | 71.0 | 67.7 | 0.070 | 63.6 | 84.2 | 0.481* |

| ≥ 4 | 29.2 | 13.9 | 0.379* | 24.7 | 14.0 | 0.274* | 18.3 | 18.3 | < 0.001 | 29.2 | 7.1 | 0.599* |

| Refractory to lenalidomide, % | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 83.4 | 48.4 | 0.795* | 75.3 | 68.1 | 0.162* | 67.7 | 63.4 | 0.091 | 83.4 | 85.0 | 0.043 |

| No/NA | 16.6 | 51.6 | NA | 24.7 | 31.9 | NA | 32.3 | 36.6 | NA | 16.6 | 15.0 | NA |

| Refractory status, % | ||||||||||||

| IMiD only | 29.6 | 49.2 | 0.408* | 36.2 | 44.0 | 0.159* | 59.1 | 60.2 | 0.022 | 29.6 | 28.9 | 0.017 |

| PI only | 6.3 | 2.5 | 0.189* | 5.2 | 5.0 | 0.010 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 0.057 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 0.088 |

| Both IMiD + PI | 54.2 | 4.9 | 1.282* | 39.4 | 25.9 | 0.291* | 9.7 | 6.5 | 0.119* | 54.2 | 55.3 | 0.024 |

| None | 9.9 | 43.4 | 0.820* | 19.2 | 25.1 | 0.144* | 26.9 | 30.1 | 0.072 | 9.9 | 11.5 | 0.051 |

| Years since diagnosis, median (IQR) |

4.7 (2.72–7.19) |

4.0 (2.45–6.22) |

0.153* |

4.4 (2.72–6.95) |

4.6 (2.91–6.95) |

0.015 |

5.0 (2.74–7.05) |

4.6 (2.83–6.95) |

0.081 |

4.6 (2.71–7.16) |

4.6 (3.11–7.49) |

0.010 |

| Prior ASCT, % | 64.8 | 69.7 | 0.103* | 66.2 | 63.0 | 0.066 | 68.8 | 68.8 | < 0.001 | 64.8 | 47.4 | 0.356* |

ASCT autologous stem cell transplant, CM cardinality matching, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ESS effective sample size, IgG immunoglobulin G, IMiD immunomodulatory drug, IQR interquartile range, ISS International Staging System, MM multiple myeloma, NA not available, PI proteasome inhibitor, PSM propensity score matching, sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, SMD standardized mean difference, Vd bortezomib and dexamethasone

aAs a result of missingness in the EQUULEUS study, the extent of imbalance for these subgroups is unknown

bMissingness was treated as a distinct value

*SMD values > 0.1

The primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS). Efficacy results were reported for the CM and sIPTW analyses only.

CM analysis used a Cox proportional hazards model for treatment effect in the matched sample and analyses were performed separately for the D-Pd versus Vd and D-Pd versus D-Vd comparisons. The sIPTW analysis used a weighted Cox proportional hazards model and weights were computed separately for the D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd comparisons.

The P values for hazard ratios (HRs) were based on a Wald test. Robust standard errors were used for sIPTW.

Harmonized Eligibility Criteria

To ensure consistency across the trials, the following harmonized inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied prior to weighting/matching. All patients received at least one prior line of anti-MM therapy, including a PI and IMiD (although not necessarily lenalidomide), and patients who had received prior pomalidomide were excluded.

The following criteria were not applied because of feasibility/sample size considerations: inclusion of only patients with prior lenalidomide (rather than any IMiD); inclusion of only patients with two or more lines of prior therapy; exclusion of patients who were refractory to a PI; exclusion of patients with only one prior line who were non-refractory to lenalidomide; and laboratory screening criteria (inclusion of only patients with hemoglobin level ≥ 7.5 g/dL [≥ 4.65 mmol/L], creatinine clearance ≥ 30 mL/min, and serum calcium corrected for albumin ≤ 14.0 mg/dL [≤ 3.5 mmol/L] or free ionized calcium ≤ 6.5 mg/dL [≤ 1.6 mmol/L]).

Covariates

Population differences across the three studies were addressed by using a covariate balancing strategy selected on the basis of the ability to achieve balance across arms and subject to data availability limitations. CM uses integer programming to maximize the size of the matched treatment and control groups subject to specified balance requirements rather than individually pairing treatment and control subjects [21]. In the sIPTW analyses, logistic regression was used to estimate propensity scores. The preferred covariates were selected on the basis of clinical input. Lower priority covariates were subject to impact on ESS [22] and balance.

In the analyses the following covariates were considered for adjustment based on clinician input: age (< 65, 65–75, ≥ 75 years), sex, refractory to lenalidomide status (yes/no/not received), refractory to IMiD/PI status (IMiD only, PI only, both, neither), number of prior lines of therapy (1, 2–3, or ≥ 4), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS; 0, 1, or 2), years since diagnosis, prior autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT; yes/no), and cytogenetic risk (high/standard/missing).

International Staging System (ISS) stage (I, II, III, or missing), MM type (immunoglobulin G/nonimmunoglobulin G/missing) were not included in the CM analysis because of missingness in the EQUULEUS dataset. For the sIPTW analysis, prior ASCT, sex, and number of prior lines were excluded from the adjustment where this was able to improve post-adjustment balance.

In the sIPTW analysis, weights were computed separately for the D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd comparisons using combined data from APOLLO (D-Pd) + EQUULEUS (D-Pd) + CASTOR (D-Vd/Vd). The estimand was the average treatment effect (ATE). CM was also performed for the D-Pd versus Vd and D-Pd versus D-Vd comparisons using combined data from the three studies. CM can be formulated to solve linear integer programming problems allowing for flexible covariate balance constraints on the entire sample.

Missingness in cytogenetic risk was treated as a distinct covariate value in the CM and sIPTW analyses, which assumed that the drivers of missingness were similar across trials. One patient treated with D-Pd with missing ECOG PS was removed from the dataset in the sIPTW and PSM analyses.

To explore the potential impact of not including ISS stage and MM type in the CM analysis as a result of missingness in EQUULEUS, a sensitivity analysis was performed in the absence of data from the EQUULEUS trial. In addition, ISS and MM type were adjusted as they were commonly reported in both CASTOR and APOLLO.

Results

Patients and Baseline Characteristics

After harmonized eligibility criteria were applied, 253, 104, and 122 patients from the D-Pd, D-Vd, and Vd cohorts, respectively, were included for comparison. This harmonization had the greatest impact on the CASTOR population and resulted in the removal of 270 patients (only 240 out of 497 CASTOR patients had received both a prior PI and IMiD). The ESS for each method and comparison are shown in Tables 1 and 2 and reduced following matching and weighting.

Pre- and post-adjustment baseline characteristics for D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd cohorts are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. A naive comparison of patient baseline characteristics before adjustment identified some differences between cohorts. In the sIPTW analysis, the distribution of computed weights for the D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd comparisons showed very few extreme weights (99th percentile of weights: 4.3 for D-Pd versus D-Vd and 6.0 for D-Pd versus Vd; trim level applied at 5).

Some differences in baseline characteristics remained for the D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd cohorts after CM, and sIPTW adjustment. As a result of missingness in the EQUULEUS study, ISS stage and MM type were not adjusted and the extent of imbalance for these subgroups is unknown. The CM analysis was associated with fewer imbalances compared to the sIPTW analysis and these were in refractory to PI only status in the D-Pd versus D-Vd cohort and in refractory to both PI and IMiD in the D-Pd versus Vd cohort. In the sIPTW analysis, remaining imbalances were in ECOG PS, cytogenetic risk, number of prior lines of therapy, refractory to lenalidomide status, and refractory to PI and/or IMiD status.

Primary Outcome: Progression-Free Survival

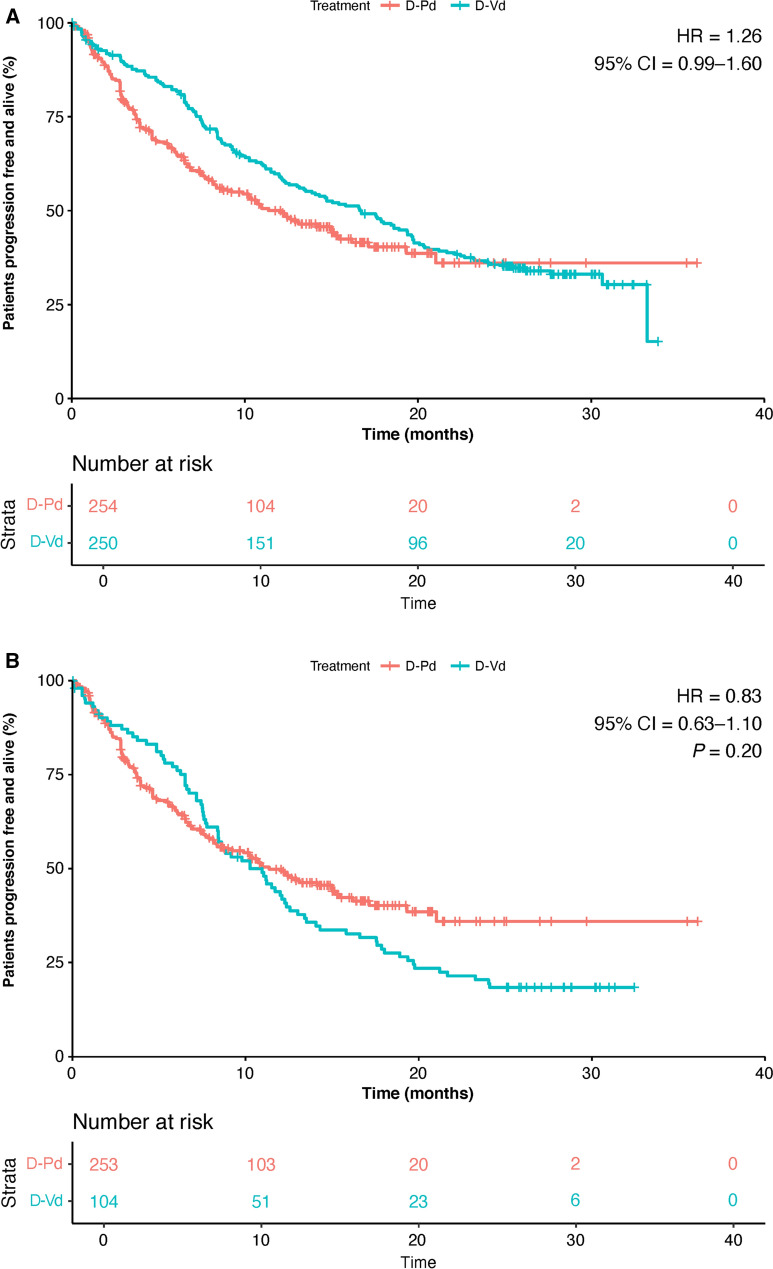

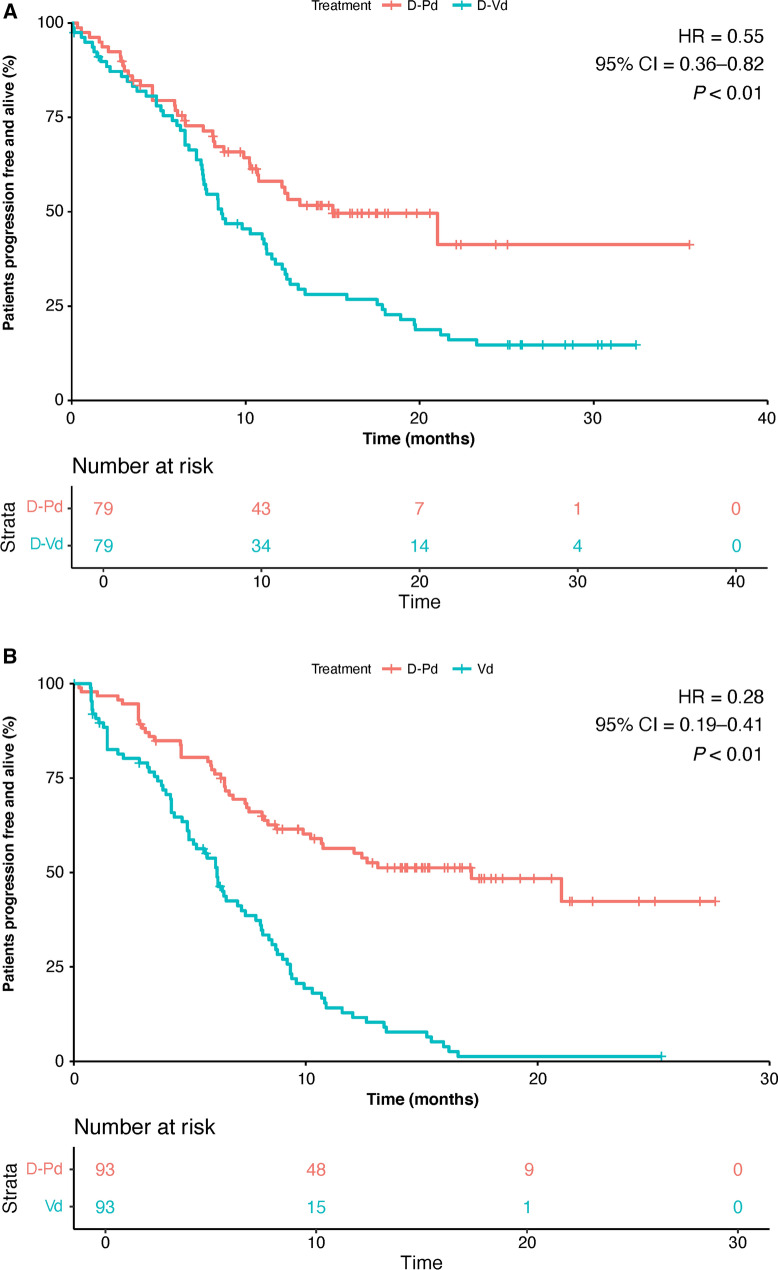

After application of harmonization criteria, the PFS Kaplan–Meier (KM) curves for the D-Vd and Vd cohorts fell compared to the D-Pd curves (Figs. 1 and 2, respectively). The PFS HRs for D-Pd versus D-Vd before and after applying harmonization criteria were 1.26 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.99–1.60) and 0.83 (95% CI 0.63–1.10, P = 0.20) (Fig. 1) and for D-Pd versus Vd were 0.49 (95% CI 0.39–0.61) and 0.42 (95% CI 0.32–0.55, P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival for D-Pd versus D-Vd a prior to harmonized exclusion criteria and b after harmonized exclusion criteria. CI confidence interval, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, D-Vd daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, HR hazard ratio

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival for D-Pd versus Vd a prior to harmonized exclusion criteria and b after harmonized exclusion criteria. CI confidence interval, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, HR hazard ratio, Vd bortezomib and dexamethasone

Cardinality Matching

The CM-adjusted PFS was significantly improved with D-Pd versus D-Vd and versus Vd. There was a statistically significant reduction in risk of disease progression of 45% for D-Pd versus D-Vd (HR, 0.55 [95% CI 0.36–0.82], P < 0.01; Fig. 3a). A significant reduction in risk of disease progression of 72% in CM-adjusted PFS was also observed with D-Pd versus Vd (HR, 0.28 [95% CI 0.19–0.41], P < 0.01); Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survival (cardinality matching). a D-Pd versus D-Vd and b D-Pd versus Vd. CI confidence interval, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, D-Vd daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, HR hazard ratio, Vd bortezomib and dexamethasone

Stabilized Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

A lowering of the PFS KM curves for the D-Vd and Vd cohorts compared to the D-Pd cohort was observed after sIPTW adjustment. The sIPTW-adjusted PFS was significantly improved with D-Pd versus D-Vd (HR, 0.66 [95% CI 0.45–0.96], P = 0.03) with a reduction in risk of disease progression of 34% with D-Pd compared with D-Vd (Fig. 4a). The sIPTW-adjusted PFS was also significantly improved with D-Pd versus Vd with a reduction in risk of disease progression of 67% for D-Pd compared with Vd (HR, 0.33 [95% CI 0.25–0.43], P < 0.01; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Progression-free survival (sIPTW adjusted). a D-Pd versus D-Vd and b D-Pd versus Vd. CI confidence interval, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, D-Vd daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, HR hazard ratio, sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, Vd bortezomib and dexamethasone

Figure 5 summarizes the adjusted PFS HRs for D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd using both sIPTW and CM analyses. Adjusted PFS HRs favored D-Pd over D-Vd and Vd and were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for both analysis methods.

Fig. 5.

Progression-free survival. Values less than 1 favor D-Pd. CI confidence interval, CM cardinality matching, D-Pd daratumumab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone, D-Vd daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, ESS effective sample size, HR hazard ratio, sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, Vd bortezomib and dexamethasone

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed without data from the EQUULEUS study. The baseline characteristics were well balanced, including for ISS stage and MM type which could not be adjusted for in the presence of the EQUULEUS data (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). PFS results in the absence of the EQUULEUS data (Supplemental Fig. 1) were similar to the CM-adjusted data including EQUULEUS. CM-adjusted PFS was improved with D-Pd versus D-Vd (HR, 0.58 [95% CI 0.38–0.87]; a reduction in risk of disease progression of 42%) and D-Pd versus Vd (HR, 0.24 [95% CI 0.16–0.35]; a reduction in risk of disease progression of 76%).

Discussion

First-line treatment in MM frequently fails after a period of initial response [3, 23]. Thus, there is a continuing need for second- and later-line treatment options and for insights on the comparative efficacy of these therapies that will help to guide clinicians when selecting the optimum treatment sequence for their patients.

Several network meta-analyses (NMA) have evaluated daratumumab-based regimens in patients with RRMM. Dimopoulos et al. [24] conducted an NMA evaluating the comparative effectiveness of daratumumab plus SOC versus other relevant options. The analysis extracted data from a systematic literature review and from the CASTOR and POLLUX trials. The results demonstrated that the daratumumab-containing regimens daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-Rd) and D-Vd were more effective in improving PFS when compared with other evaluated regimens. In a recent NMA by Kiss et al. [25], better clinical outcomes were demonstrated in patients with RRMM treated with daratumumab-containing vs control regimens with regards to minimal residual disease negativity, stringent complete response, death, and disease progression. Additionally, in an NMA by Luo et al. [26], which synthesized results from 24 randomized controlled trials, it was demonstrated that D-Rd showed better efficacy than the other regimens with regards to nonresponse rate, time to progression, and PFS. D-Rd also ranked first with respect to overall efficacy. To date, limited comparisons between D-Pd and other RRMM regimens have been published [27].

In the current analysis, patient-level data were used to compare improvement in PFS with D-Pd versus D-Vd and Vd in patients with RRMM and prior PI and IMiD exposure. Results were generally consistent regardless of which adjustment technique was used. All adjusted PFS HRs favored D-Pd over D-Vd and Vd and were statistically significant for both D-Pd versus D-Vd and D-Pd versus Vd using CM and sIPTW. In general, CM results were similar to post-sIPTW results, although direct comparison is complicated by the different estimands that were used (nonspecific estimand for CM and ATE for sIPTW).

Outcomes may have been driven by the fact that patients in the APOLLO study were more difficult to treat than those in the CASTOR study. This was due to more patients in the APOLLO study being refractory to PI and IMiD and more patients receiving later lines of therapy. The analysis attempted to adjust for differences in eligibility criteria and patient baseline characteristics.

Limitations

In the absence of direct head-to-head comparisons, ITCs can provide important information to help optimize treatment for patients with RRMM. However, ITCs of aggregated clinical trial data can be subject to selection and confounding bias, thus limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from the comparison. The results of the ITC analyses must be interpreted with caution as even after the ITC, patient selection differences remained between the patient populations from the three studies.

Differences in eligibility criteria with respect to prior therapy and refractory status to prior therapies also presented a challenge. EQUULEUS eligibility required at least two prior lines of therapy, whereas eligibility in the APOLLO and CASTOR trials required at least one prior line. However, CM-adjusted results from the sensitivity analysis in the absence of EQUULEUS data showed no differences from the analyses in the presence of the EQUULEUS data.

In addition, while the small ESS for D-Vd and Vd precluded a meaningful comparison of PFS using PSM analysis, satisfactory results were achieved using CM analysis.

Covariate imbalances remained after sIPTW adjustment and may have resulted in residual confounding; therefore, the adjusted HRs for the sIPTW analysis should be interpreted with caution. The use of CM can potentially overcome limitations in matching methods that can fail to achieve covariate balance or result in small sample sizes. Because computer power was historically limited, it only started being widely used recently and, unlike a traditional PSM approach, CM maximizes the size of matched samples that meet pre-specified criteria for covariate balance. This method can make use of more observations than other approaches when there is limited overlap in covariate distributions.

Although the CM method yielded better balance than sIPTW and PSM, the inability to adjust for differences in ISS staging or MM type between arms due to confounders that were not reported was a limitation. However, the sensitivity analysis performed without the EQUULEUS trial did adjust for ISS and MM type and demonstrated similar results to the analyses in the presence of the data from EQUULEUS.

Another limitation is that no imputation of the “missing” category of cytogenetic risk profile was conducted. By matching with the “missing” category, we assumed that both cohorts included the same proportion of high- or standard-risk patients among those with missing values.

This study was also limited by the lack of mature overall survival (OS) data for inclusion in the ITC analyses, which evaluated PFS outcomes only. Although OS is considered the gold standard outcome measure in MM studies [28], OS for D-Pd in the APOLLO trial at a median follow-up of 16.9 months is still premature. However, PFS has been recognized as a surrogate endpoint used to evaluate primary efficacy in clinical trials for hematological malignancies, including MM [29, 30]. Lastly, the proportional hazards assumption was violated for the CM and sIPTW D-Pd versus Vd comparisons so the corresponding HRs should be interpreted as rough averages over the follow-up period.

Furthermore, differences in dosing schedule between the three different regimens should also be noted: D-Pd was delivered as a continuous therapy, Vd as a fixed duration therapy, and the D-Vd regimen was partly discontinued after induction.

Despite these limitations ITCs offer a valuable alternative to head-to-head trials that can be used to leverage results from clinical trials that share a common comparator arm. Comparisons using individual patient-level data for at least one of the treatment arms of interest produce stronger results than those using aggregate data. For ITC results to be considered valid, populations must be sufficiently similar; as shown in the ITC analyses, different techniques can be applied to balance baseline characteristics so that cohorts are more similar.

Conclusions

The results of this ITC demonstrated a PFS benefit for D-Pd compared with D-Vd and Vd in patients with RRMM with previous exposure to a PI and an IMiD. Results were generally consistent irrespective of the type of adjustment used. Despite the inability to adjust for ISS stage and MM type and the residual imbalances between treatment cohorts, these findings provide support in favor of using D-Pd in a population of patients with difficult-to-treat RRMM who have been exposed to both a PI and an IMiD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding.

The analysis, and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees, were funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

Medical Writing and Editing Assistance.

Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Karen Pemberton, PhD, of Eloquent Scientific Solutions, and was funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

Authorship.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions.

Jianming He, Tobias Kampfenkel, Harikumaran R. Dwarakanathan, Stephen Johnston, João Mendes, Annette Lam, and Sacheeta Bathija contributed to the study design and data interpretation. Bart Heeg, Haoyao Ruan, Emma K. Mackay, and Heather Berringer performed the analyses. All authors contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript, approved the final version, decided to publish this analysis, and can vouch for data accuracy and completeness.

Prior Presentation.

The data in this manuscript were partially presented at the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting & Exposition; December 11–14, 2021; Atlanta, GA/Virtual.

Disclosures.

Jianming He, Tobias Kampfenkel, Stephen Johnston, João Mendes, Annette Lam, and Sacheeta Bathija are employed by Janssen. Harikumaran R. Dwarakanathan was contracted by Janssen to perform analyses for this study. Bart Heeg served in a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Merck KGaA, Pfizer, and Sanofi; received research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Merck KGaA, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and is employed by Ingress, which was contracted by Janssen to conduct these analyses. Emma K. Mackay, Haoyao Ruan, and Heather Berringer are employed by Cytel (Ingress), which was hired by Janssen to conduct these analyses.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines.

No institutional board review was required for this study as it evaluated patient-level data from the APOLLO, CASTOR, and EQUULEUS trials. Those trials involved human participants and were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the local institutional research committees and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in each trial.

Data Availability.

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinicaltrials/transparency. Requests for access to the CASTOR and APOLLO study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1046–1060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Donk N, Pawlyn C, Yong KL. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2021;397:410–427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtin S. Relapsed or relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013;4:5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:94. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-00359-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonneveld P. Management of multiple myeloma in the relapsed/refractory patient. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017:508–517. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Multiple Myeloma, Version 5.2022. 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2022.

- 8.Lancman G, Sastow DL, Cho HJ, et al. Bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma: present and future. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2:423–433. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Donk N, Usmani SZ, Yong K. CAR T-cell therapy for multiple myeloma: state of the art and prospects. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e446–e461. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overdijk MB, Jansen JH, Nederend M, et al. The therapeutic CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab induces programmed cell death via Fcgamma receptor-mediated cross-linking. J Immunol. 2016;197:807–813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:80–97. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Boccadoro M, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma (APOLLO): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:801–812. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:754–766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chari A, Suvannasankha A, Fay JW, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;130:974–981. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-785246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson E, Morley R, Lucas A, Carpenter J. Propensity scores: from naive enthusiasm to intuitive understanding. Stat Methods Med Res. 2012;21:273–293. doi: 10.1177/0962280210394483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visconti G, Zubizarreta J. Handling limited overlap in observational studies with cardinality matching. Observ Stud. 2018;4:217–249. doi: 10.1353/obs.2018.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zubizarreta J. Using mixed integer programming for matching in an observational study of kidney failure after surgery. J Am Stat Assoc. 2012;107:1360–1371. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2012.703874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niknam BA, Zubizarreta JR. Using cardinality matching to design balanced and representative samples for observational studies. JAMA. 2022;327:173–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zubizarreta J, Paredes RD, Rosembaum P. Matching for balance, pairing for heterogeneity in an observational study of the effectiveness of for-profit and not-for-profit high schools in Chile. Ann Appl Stat. 2014;8:204–231. doi: 10.1214/13-AOAS713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillipo D, Ades A, Dias S, Palmer S, Abrams K, NJ W. NICE DSU technical support document 18: methods for population-adjusted indirect comparisons in submissions to NICE. http://nicedsu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Population-adjustment-TSD-FINAL-ref-rerun.pdf Accessed 13 Jan 2022.

- 23.Robak P, Drozdz I, Szemraj J, Robak T. Drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;70:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dimopoulos MA, Weisel K, Kaufman JL, et al. Efficacy and safety of daratumumab-based regimens in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma—a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:E63. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2017.03.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiss S, Gede N, Hegyi P, et al. Addition of daratumumab to multiple myeloma backbone regimens significantly improves clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21916. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01440-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo XW, Du XQ, Li JL, Liu XP, Meng XY. Treatment options for refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma: an updated evidence synthesis by network meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2817–2823. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S166640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leleu X, Delea T, Guyot P, Moynahan A, Singh E, Lin P. Comparative efficacy and safety of isatuximab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Value Health. 2022;25:S39. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holstein SA, Suman VJ, McCarthy PL. Should overall survival remain an endpoint for multiple myeloma trials? Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019;14:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s11899-019-0495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimopoulos MA, Sonneveld P, Nahi H, et al. Progression-free survival as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Value Health. 2017;20:PA408. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration. Table of surrogate endpoints that were the basis of drug approval or licensure. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/table-surrogate-endpoints-were-basis-drug-approval-or-licensure Accessed 17 Nov 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinicaltrials/transparency. Requests for access to the CASTOR and APOLLO study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.