Abstract

Introduction and importance

Triple-valve replacement in active infective endocarditis has rarely been reported. This paper is the first report of a triple-valve replacement performed in endocarditis with septic shock and the first presentation of multivalvular endocarditis due to Rhizobium radiobacter.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old patient with a neglected ventricular septal defect referred to us in septic shock, with multiple organ failure, severe biventricular dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension, due to Rhizobium radiobacter infective endocarditis affecting the aortic, tricuspid and pulmonary valves. Initially, he was deemed unfit for surgery. However, after clinical stabilization, triple-valve replacement, aortic annular abscess repair, membranous septum aneurysm resection, and ventricular septal defect patch closure were performed. The postoperative evolution was good; both ventricles showed functional recovery after six months.

Clinical discussion

Although surgery provides the best chances of survival in endocarditis with septic shock, reportedly, most cases are considered inoperable. Clinical stabilization under intensive care using specific therapies to manage septic shock, myocardial dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension was crucial for surgery success. Custodiol® cardioplegia, and replacement of the right-sided valves using a beating-heart technique were used to reduce the myocardial ischemic time.

Conclusion

Rhizobium radiobacter, an opportunistic gram-negative bacterium, potentially may cause multiple valve endocarditis. Patients with endocarditis and septic shock initially considered inoperable can still benefit from surgery after tenacious intensive care (cytokine hemoadsorption and levosimendan are helpful in this process). In complex multivalvular procedures, a beating heart technique to replace the right-sided valves should be considered to minimize the duration of myocardial ischemia.

Keywords: Triple-valve replacement, Infective endocarditis, Rhizobium radiobacter, Septic shock, Ventricular septal defect, Case report

Highlights

-

•

First report of a triple-valve replacement in endocarditis with septic shock

-

•

First report of Rhizobium radiobacter causing multiple valve endocarditis

-

•

Tenacious intensive care of septic shock in endocarditis improves surgical chances.

-

•

The use of cytokine hemoadsorption in endocarditis with septic shock was effective.

-

•

Beating-heart replacement of right-sided valves reduces myocardial ischemic time.

1. Introduction

Triple-valve surgery is rarely performed in infective endocarditis (IE) (<2 % of procedures in the Italian IE Registry) [1], and triple-valve replacement in IE is even less often: a 2018 review of the literature identified only six reported cases [2]. We report a case of Rhizobium radiobacter (R. radiobacter) triple-valve IE presented in septic shock affecting a young patient with neglected ventricular septal defect (VSD). R. radiobacter is an aerobic gram-negative nitrogen-fixing soil bacterium [3]. It is an opportunistic germ rarely pathogenic to humans [4] and exceptionally causes IE [5], [6], [7]. We report the first triple-valve replacement in IE with septic shock and the first case of multivalvular R. radiobacter IE, according to the SCARE 2020 guidelines [8].

2. Case presentation

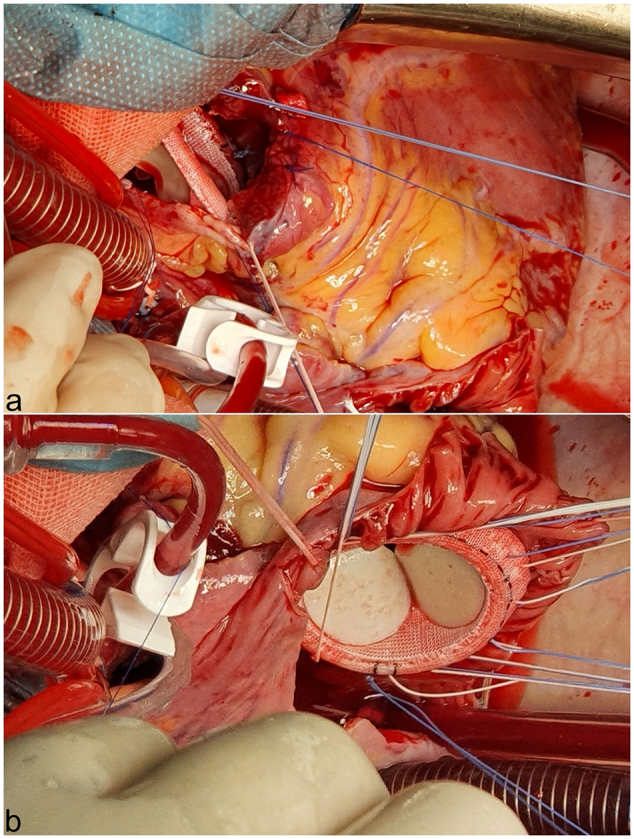

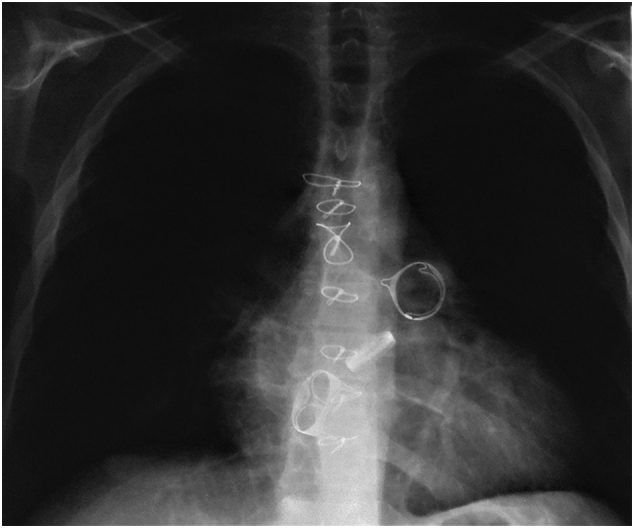

A 26-year-old male patient, previously diagnosed with a restrictive subaortic VSD and mild pulmonary hypertension (PHT), with no history of drug abuse, presented to the hospital in a critical condition. Nine months before admission, the patient was diagnosed with hypochromic anemia after accusing fatigue and effort limitation; gradually, his clinical condition worsened: he developed exertional dyspnea, ascites, persistent inflammatory syndrome, and loosed 20 kg in weight. At admission, he presented increased blood cell count (WBC) > 20,000/mm3, C-reactive protein = 76 mg/L, procalcitonin = 0.77 ng/mL, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Echocardiography revealed IE with mobile vegetations and severe regurgitation of the aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonary valves (Fig. 1a-c; Video 1a, Video 1b, Video 1c); an aortic annulus abscess; a restrictive VSD (Fig. 1d; Video 1d); severely dilated left ventricle (LV, 71/58 mm); a dilated right ventricle (45 mm), severe biventricular dysfunction - LV ejection fraction (LVEF = 25 %), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE = 11 mm) -; severe PHT (70 % of the systemic blood pressure - SBP). After harvesting blood cultures, a treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals was initiated; however, the patient developed septic shock with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). The patient was hypotensive (systolic arterial pressure = 60 mmHg), hypoxemic (O2 arterial saturation 92 %, despite supplemental oxygen), with severe metabolic acidosis (pH = 7.09, lactate = 10.5 mmol/L), oliguria, thrombocytopenia (platelet count = 30,000/mm3) and neurologic dysfunction (with normal cerebral computed tomography). Mechanical ventilation, hemodynamic support with dobutamine (10 μg/kg/min) and norepinephrine (300 ng/kg/min), and continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) using a cytokine removal filter (CytoSorb, CytoSorbents Europe GmbH, Berlin, Germany) were performed. The patient was presented to the surgeon shortly after the septic shock had developed and was considered too ill to withstand the major surgical procedure required due to his poor clinical condition. Gram-negative bacilli were found on blood cultures but could not be identified due to slow growth. Meropenem (3 × 2 g/day) was prescribed. Gradual clinical improvement allowed weaning of norepinephrine and mechanical ventilation (after a week of treatment); most organ functions recovered; the ventricular function slightly improved (LVEF = 30 %; TAPSE = 16). However, the pulmonary artery pressure was still elevated (50–60 % of systemic pressure), and the patient remained dobutamine-dependent. On the 16th day of treatment, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), a septic discharge (fever >39 °C, and WBC increase), and recurrence of septic shock occurred; it generated hemodynamic deterioration, with lactate increase (12 mEq/L), transient hepatic cytolysis, and oliguria. The clinical condition improved after electrical conversion to sinus rhythm, administration of dobutamine and levosimendan. The imminence of clinical deterioration was a crucial argument in favor of surgery performed by a senior surgeon (the first author) on the 18th day after admission, two days after the recurrent septic shock had occurred. We used bicaval-aortic cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and Custodiol® (Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) crystalloid cardioplegia (1800 at 4 °C, in antegrade intraostial administration, supplemented retrogradely with half the initial dose, after 90 min of cross-clamping). The affected valves were damaged beyond repair. The aortic valve showed ruptures and large vegetations (>10 mm) on the noncoronary and right coronary cusps; the tricuspid anterior and septal leaflets exhibited even larger vegetations (≈15 mm) and rupture; the pulmonary valve had vegetations (5–10 mm) on all cusps (one of them was flail). An already drained aortic annular abscess found below the noncoronary cusp was debrided and closed; there was no annular damage to the right-heart valves. A membranous septum aneurysm containing vegetations surrounded a 10 mm VSD. Most of the aneurysmal wall was resected; the VSD thus enlarged and closed with a bovine pericardial patch. The aortic valve was replaced with a bileaflet mechanical prosthesis (Carbomedics Standard 25, CarboMedics, Inc.; Austin, Tex), while the tricuspid and pulmonary were replaced on an empty beating heart with EdwardsPerimount bioprostheses of size 33 and 27, respectively (Edwards Lifesciences, Irving, CA) (Fig. 2a and b). Sinus rhythm was recovered early, which helped avoid a complete atrioventricular block during tricuspid valve replacement. CPB was weaned off using dobutamine (9 μg/kg/min), norepinephrine (300 ng/kg/min), and inhaled nitric oxide (i-NO, 15 ppm). The CPB and aortic cross-clamping times were 234 and 126 min, respectively. Ultrafiltration with cytokine removal was performed during CPB.

Fig. 1.

(a) Vegetations on ruptured aortic valve (2D-TTE). (b) Vegetations on anterior and septal tricuspid leaflets (2D-TEE). (c) Vegetations on flail pulmonary cusps (2D-TEE). (d) Flow acceleration through the ventricular septal defect (2D-TEE).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative images of right-heart valves replacement on a beating heart: (a) Pulmonary valve replacement. (b) Tricuspid valve replacement.

The postoperative outcome was good (Table 1 and Fig. 3), with stable hemodynamics and no arrhythmias. After extubation, on postoperative day 1, i-NO was replaced by a Milrinone infusion. Another levosimendan administration allowed inotrope withdrawal on the fourth postoperative day. As the LVEF remained below 35 %, a sacubitril/valsartan treatment was started before discharge.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the clinical evolution under treatment.

| Admission | Shock + MODS | Treated shock | Recovery from shock | Septic discharge 2nd shock | Preop. day | OP Day | POD 1 | POD 2–5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital day | 1 | 2–4 | 5–8 | 9–15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20–24 |

| Ventilation | SpV | MV | MV | SpV | NIV | SpV | MV | SpV | SpV |

| SBP (mmHg) | 90 | 60–90 | 100 | 120 | 70 | 100 | 90 | 120 | 110–120 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 65 | 50–65 | 60 | 65 | 45 | 55 | 40 | 40 | 35 |

| Urine output | N/A | ↓ | N | N | ↓ | N | N | N | N |

| Glasgow coma score | 12 | Sedated | 11 | 15 | 12 | 15 | Sedated | 14 | 15 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 10.5 | 10–2 | 1 | 0.7–1.2 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | <1 |

| WBC (CC/mcL) | 24,000 | 21,000 | 11,000 | 8000- | 10,000 | 11,300 | 11,000 | 12,500 | 10,000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7 | 8.5 | 7–8 | 8 | 9 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

| Platelet count/mm3 | 30,000 | 21,000 | <100,000 | >200,000 | 300,000 | 166,000 | 77,000 | 107,000 | ≈130,000 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 76 | ↑… 100 | ↑…130 | ↓…28 | 30 | 41 | 55 | 100 | ↓…45 |

| Procalcitonin (mcg/L) | 0.77 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 22 | 14 | 13 | ↓…0.17 |

| Urea/creatinine | 69 | ↑…107 | ↓… 65 | 38 | 40 | 58 | 49 | 93 | ↓…40 |

| Creatinine | 1.4 | ↑… 3 | ↓… 1.1 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.7 | 1.56 | 1.09 | 1.28 | ↓…0.5 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 55 | ↑… 61 | ↓…24 | 27 | 23 | 1418 | 1194 | 920 | ↓…244 |

| AST (IU/L) | 72 | ↑…93 | ↓…31 | 22 | 37 | 3109 | 1681 | 1237 | ↓…58 |

| Dobutamine (mcg/kg/min) | 10 | 6–4 | 2–0–6–2 | 10 | 6 | 9 | – | – | |

| Noradrenaline (ng/kg/min) | – | 300 | 150–20 | – | 100 | – | 300 | – | – |

| CVVHD + CytoSorb | X | X | X | ||||||

| Levosimendan | X | X | X | ||||||

| i-NO | X | ||||||||

| Milrinone | X | X | |||||||

| Meropenem 3 × 2 g/day | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Vancomycin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Abbreviations: ALT - alanine aminotransferase; AST - aspartate aminotransferase; CVVHD - continuous venovenous hemodialysis; i-NO - inhaled nitric oxide; MV - mechanical ventilation; N - normal; N/A - non-available; NIV - noninvasive ventilation; PASP - pulmonary artery systolic pressure; POD- postoperative day; PSVT - paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia; SBP - arterial systolic blood pressure; SpV - spontaneous ventilation; X - the treatment was used.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative chest X-ray showing the relative position of the aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonary valvular prostheses.

Valve cultures were positive for R. radiobacter (sensitive to piperacillin, ticarcillin, cefepime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, carbapenems, amikacin, levofloxacin, co-trimoxazole). The postoperative treatment included four weeks of intravenous meropenem, followed, after discharge, by levofloxacin and co-trimoxazole. At six months, the patient had resumed work; he had normally functioning valves, improved function of both ventricles, and no sign of infection. At 18 months of follow-up, he was still asymptomatic, under the sacubitril/valsartan treatment; the LVEF was 50 %.

3. Discussion

Triple-valve replacement for active IE is highly infrequent: besides the six cases gathered by Kadado [2], we only found three more [9], [10], [11]. None of these nine cases combined underwent surgery after septic shock. Seven of them required mitral-aortic-tricuspid replacement. One-third of all cases were VSD-associated. Reportedly, a VSD increases the risk of IE by over 20-fold [12]. Our patient's neglected VSD was probably at the origin of his endocarditis. VSD-associated IE most often affects the aortic and tricuspid valves, but pulmonary involvement was also reported [13]. However, simultaneous involvement of both right-sided valves in IE is exceptional; aortic-tricuspid-pulmonary triple valve replacement in endocarditis was only once reported [14]. In the present case, the membranous septum aneurysm was probably the first affected structure: it showed clear marks of endocarditis; the infection had extended to the nearby aortic and tricuspid valves and spread by blood only to the pulmonary, leaving an unaffected mitral valve.

The initial shock was mainly septic, with a clear cardiogenic contribution to its etiology. It induced MODS involving five organs and systems. The surgical decision in multiple valves IE with septic shock is problematic: one has to balance a high surgical mortality rate and the unsatisfactory results of a conservative approach. Although surgery provides the best chances of survival in IE with septic shock, reportedly, most cases are considered “too ill to withstand surgery” [15]. Initially, we also refrained from surgery. However, tenacious intensive care has achieved clinical stabilization justifying a reasonable hope for the patient's postoperative survival. Specific therapies for septic shock, myocardial dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension: cytokine hemoadsorption (CytoSorb) [16], levosimendan [17], and i-NO were crucial in the initial approach and the perioperative management, as well.

The triple valve replacement was expected to be a lengthy procedure. To diminish the duration of aortic cross-clamping, we used Custodiol® cardioplegia and replaced both right-sided valves using a beating heart technique. This latter option also reduced the CPB time because much of the post-ischemic on-pump circulatory assistance occurred during the beating heart replacement of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

The choice of a valve substitute for the right-sided valves in young individuals is debatable. We opted to replace the tricuspid and pulmonary with tissue valves, considering our grim experience with mechanical prostheses implanted in the right heart; in addition, the patient lived far away from a specialized medical establishment. As the valve-in-valve procedures become standard practice, the eventuality of a bioprosthetic valve disease seems to have better prospects.

Our study also shows that R. radiobacter, known as an opportunistic pathogen, source of catheter-related bloodstream infections [18], but rarely at the origin of IE, potentially may cause extensive infectious destruction of multiple valves even in young immunocompetent individuals.

This case shows that endocarditis should be suspected in any VSD presenting with fever or leukocytosis. It also pleads for prophylactic antibiotics for invasive procedures in adults with a patent VSD.

4. Conclusion

Patients with endocarditis and septic shock initially considered inoperable can still benefit from surgery after tenacious intensive care. The use of cytokine hemoadsorption therapy and levosimendan are helpful in this process. In complex multivalvular procedures, one should consider replacing the right-sided valves with a beating heart technique to minimize the duration of myocardial ischemia. R. radiobacter can potentially cause multiple valve infectious destruction.

Sources of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Case reports are exempted from ethical approval in our institutions.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

AGI: Concept/Design, Data collection/analysis/interpretation, Drafting the article, Critical revision of the article, Approval of the article; IM, AP, ATT, ELA: Data collection/analysis/interpretation, Drafting the article, Critical revision of the article, Approval of the article; VAI: Critical revision of the article, Approval of the article.

Research registration

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Andrei George Iosifescu MD, PhD.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107401.

Appendices. Supplementary data

Vegetations on ruptured aortic valve (2D-TTE).

Vegetations on anterior and septal tricuspid leaflets (2D-TEE).

Vegetations on flail pulmonary cusps (2D-TEE).

Flow acceleration through the ventricular septal defect (2D-TEE).

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Della Corte A., Di Mauro M., Actis Dato G., Barili F., Cugola D., Gelsomino S., et al. Surgery for prosthetic valve endocarditis: a retrospective study of a national registry. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017;52:105–111. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadado A.J., Grewal V., Feghali K., Hernandez-Montfort J. Triple-valve endocarditis in a diabetic patient: case report and literature review. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2018;14:217–224. doi: 10.2174/1573403X14666180522124621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahoor B.A. Rhizobium radiobacter endocarditis in an intravenous drug user: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016;35:206. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai C.C., Teng L.J., Hsueh P.R., Yuan A., Tsai K.C., Tang J.L., et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Rhizobium radiobacter infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:149–153. doi: 10.1086/380463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halas R., Jacob C., Badwal K., Mir R. Rare case of Rhizobium radiobacter bioprosthetic mitral valve endocarditis. IDCases. 2017;10:88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra N.C., Nobre A., Cravino J. Native mitral valve endocarditis due to Rhizobium radiobacter - first case report. Rev. Port. Cir. Cardiotorac. Vasc. 2013;20:203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piñerúa Gonsálvez J.F., Zambrano Infantinot Rdel C., Calcaño C., Montaño C., Fuenmayor Z., Rodney H., et al. Endocarditis infecciosa por Rhizobium radiobacter. Reporte de un Caso [Infective endocarditis by Rhizobium radiobacter. A case report] Investig. Clin. 2013 Mar;54:68–73. [Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohyama Y., Nihei T., Kimura K., Yakuwa H., Uchino K., Ishikawa T., et al. A case of ventricular septal defect associated with active infective endocarditis which was successfully treated by triple valve replacement and ventricular septal defect patch closure. Kokyu To Junkan. 1991;39:1049–1053. [Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim T.Y., Kim K.H. Simultaneous triple valve replacement for triple valve infective endocarditis with intact cardiac skeleton. J. Card. Surg. 2020;35:260–263. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa H., Honda T., Yamasawa T., Kanaoka Y., Tanemoto K. A surgical case of triple valve replacement for triple valve endocarditis with multiple vegetations. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020;68:1333–1336. doi: 10.1007/s11748-019-01269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berglund E., Johansson B., Dellborg M., Sörensson P., Christersson C., Nielsen N.E., et al. High incidence of infective endocarditis in adults with congenital ventricular septal defect. Heart. 2016;102:1835–1839. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Filippo S., Semiond B., Celard M., Sassolas F., Vandenesch F., Ninet J., et al. Caractéristiques de l'endocardite infectieuse sur communication interventriculaire chez l'enfant et l'adulte [Characteristics of infectious endocarditis in ventricular septal defects in children and adults] Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 2004;97:507–514. [French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakakura K., Kubo N., Katayama T., Umemoto T., Oosawa S., Murata S., et al. Successfully treated triple valve infective endocarditis: a case report. J. Cardiol. 2005 Jun;45(6):257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krajinovic V., Ivancic S., Gezman P., Barsic B. Association between cardiac surgery and mortality among patients with infective endocarditis complicated by sepsis and septic shock. Shock. 2018 May;49(5):536–542. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Träger K., Skrabal C., Fischer G., Datzmann T., Schroeder J., Fritzler D., et al. Hemoadsorption treatment of patients with acute infective endocarditis during surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass - a case series. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2017;40:240–249. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belletti A., Jacobs S., Affronti G., Mladenow A., Landoni G., Falk V., et al. Incidence and predictors of postoperative need for high-dose inotropic support in patients undergoing cardiac surgery for infective endocarditis. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018 Dec;32(6):2528–2536. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C.Y., Hansen K.S., Hansen L.K. Rhizobium radiobacter as an opportunistic pathogen in central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection: case report and review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;68:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Vegetations on ruptured aortic valve (2D-TTE).

Vegetations on anterior and septal tricuspid leaflets (2D-TEE).

Vegetations on flail pulmonary cusps (2D-TEE).

Flow acceleration through the ventricular septal defect (2D-TEE).

Supplementary material