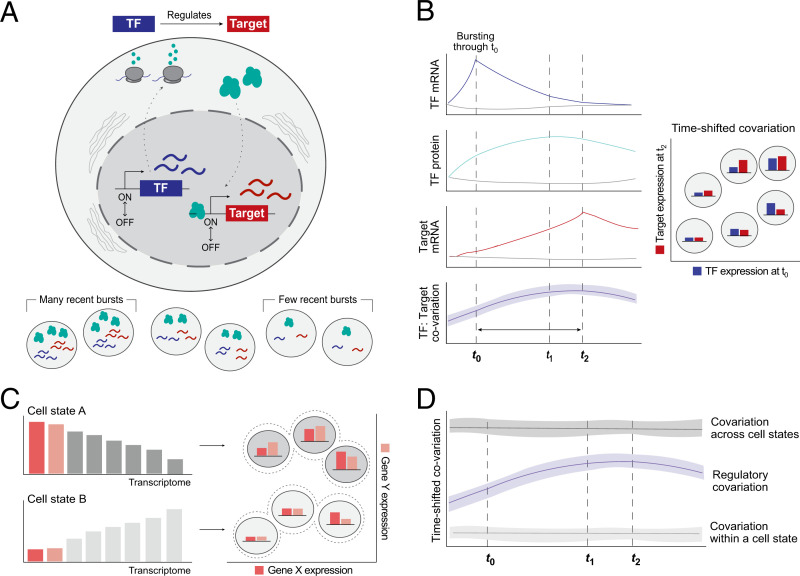

Fig. 1.

Overview of the conceptual framework for inferring TF:Target gene regulation from single cells at steady state. (A) Transcriptional bursting leads to stochastic variation in the mRNA abundance of each gene, even within a population of isogenic cells at steady state. We invoke stochastic transcriptional bursting as a source of TF mRNA heterogeneity across steady-state cell populations. If a TF directly regulates a target gene, we hypothesize that their abundances will be correlated. (B) Idealized representation of the hypothesized time-shifted correlation between a TF and its target gene’s mRNA abundances in the presence of regulation. Colored lines indicate the average behavior of cells that had at least one burst of the TF gene; gray lines represent those that did not have a burst. The time delay reflects the time required for TF mRNA translation into protein, translocation, and target site search in the nucleus. From left to right, dotted lines reflect the time of maximal TF mRNA (t0), TF protein (t1), or target mRNA abundance (t2), respectively. (C) Subpopulations of cells (i.e., cell states, such as cells in different stages of the cell cycle) will also give rise to covariation—in this example, due to different baseline mRNA counts for genes in each state. Thus, correlation does not always imply regulation. (D) We can theoretically distinguish between regulation- and state-based covariation by looking at the shape over time: State-based covariation will tend to be more stable.