Abstract

The provision of informal care presents a significant global challenge. To better understand how cultural factors underpin and shape motivations and willingness to provide informal care for adults, an in-depth qualitative synthesis was conducted. Six electronic databases and a wide range of additional sources were searched. Following meta-ethnographic guidelines, 37 qualitative studies were synthesised. Six main concepts were identified: cultural self-identity, which appeared as an overarching explanatory concept; cultural duty and obligations; cultural values; love and emotional attachments; repayment and reciprocity; and competing demands and roles. These concepts informed a model of cultural caregiving motivations, offering an inductive-based exploration of key cultural motivators and highlighting implications for theory development, future research, policy and practice. The model holds implications for the actual exchange of care. Caregiver motivations should not be taken for granted by healthcare or social care professionals involved in assessment and support planning, educational endeavours at a population level may support caregiving, and support should be sensitive to cultural caregiving motivations.

Keywords: informal caregiving, meta-ethnography, culture, self-identity, motivations to provide care, willingness to provide care, systematic review

Introduction

Informal caregiving is the provision of typically unpaid care to a relative or friend with a chronic illness, disability or other long-lasting health and care needs (Revenson et al., 2016). An ageing population, smaller family size and greater geographic and social mobility place considerable demands on informal caregivers whose contribution to the sustainability of health and social care systems is significant (Bei et al., 2021; Börsch-Supan, 2019). Given the importance informal caregiving holds for society, it is essential to understand what motivates people to provide informal care. This review explores the role of culture as an important factor underpinning caregiving motivations and willingness to provide care.

Culture can be considered a system of symbols composed of both explicit and implicit shared values, meanings and norms that are manifest in acquired patterns of behaviours (Kavanagh & Kennedy, 1992). Culture comprises the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people and manifests in the form of language, philosophy, social habits, music and arts (Zimmermann, 2015). The anthropologist Geertz defines culture as ‘a set of control mechanisms - plans, recipes, rules, constructions, what computer engineers call programs for the governing of behaviour’ (Geertz, 1973, p. 44). The control mechanisms are assimilated and internalized through an ongoing process of socialisation, yet they can be imperfectly reflected in behaviour because of conflicting value priorities, variations in cognitive interpretations or resistance to the control imposed by the cultural rules (Geertz, 1973). Situational circumstances may limit people’s ability to realise the cultural ideal (e.g. people may be less willing to provide care if they are employed).

Models of health and illness vary across and within cultures (Baca Zinn & Wells, 2000; Chalmers, 1996; R. Ng & Indran, 2021). Culture can have many effects on caregiving expectations and behaviours, such as the definitions of what constitutes ‘good’ and ‘bad’ care, motivations to provide care (why/how people provide care), concepts of caregiver distress or burden, and caregiver illness beliefs (how a caregiver views the care recipient’s health or illness; Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2005; Ivey et al., 2013; Parveen et al., 2011). For example a person with cultural beliefs rooted in karma may see caregiving as repaying debts from previous life or lives (Hinton et al., 2008).

Caregiving is culturally constructed in society (Ng & Indran, 2021). A previous systematic review has described (yet not explained) the role of cultural values and norms in informing motivations to provide care (Zarzycki, Morrison, et al., 2022). Informal caregivers actively shape their own culture(s) by assimilating, sharing and cultivating the specific values, meanings, and behavioural norms relating to informal care that they learn as norms in their culture(s). For example in East Asia, where the cultural norms regarding filial piety regulate family behaviour, caring for ageing parents may be a matter of both caregiver duty and honour to which they ascribe a significant value (Yiu et al., 2021).

Previous research has highlighted the impact of caregiving motivations and willingness on caregiver outcomes. Studies showed that intrinsic motives, that is those considered to emerge from internal influences such as love toward the care recipient, are associated with more positive caregiver outcomes than extrinsic motives, which are directed by external influences such as social expectations. Differences were noted in coping strategies, emotional distress, feelings of burden, quality of care, caregiver satisfaction and stress (Knight & Sayegh, 2010; Losada et al., 2010; Lyonette & Yardley, 2003; Parveen et al., 2011, 2013). However, research on extrinsic motivations (Burridge et al., 2007; Rohr & Lang, 2016) also highlights their potential positive impact on caregiver outcomes. There are studies which evidenced the effect of a lack of caregiving willingness on caregiver outcomes, for example Burridge et al. (2007) found that when care is provided reluctantly, it may result in a deterioration of the caring relationship. Another study (Camden et al., 2011) found that those who were less willing to provide care reported higher abusive behaviours towards the care recipient and the care recipient was more likely to be admitted to a care home. The available research on caregiving motivations and willingness, although limited in scope, highlights the significance of these constructs and their potential association with caregiver outcomes. The current review builds on this evidence base by exploring cultural motivations and willingness for caring.

Evidence of differences in cultural and familial norms suggests that expectations surrounding informal care, and motivations or willingness to provide care, may vary across cultures. For example cultural expectations that children will take care of their parents and sanctions if they do not undertake the role are stronger in Japan than in the United States (Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006). In Japan, family caregiving can be considered a common and expected part of relationships, especially for women – daughters-in-law and spouses (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2005; Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006). Whilst previous research addressing a caregiver’s physical and emotional burden and unmet needs (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2005; Harris & Long, 1999; Kavanagh & Kennedy, 1992; Parveen et al., 2013) highlighted the influence of culture and/or ethnicity, the data is too limited and heterogenous to enable reliable cross-cultural comparisons. Nonetheless, the literature suggests that caregiver motives, adaptation to the caregiver role and the way caregiving manifests itself may be culturally bound (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Bradley et al., 2004; Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2005; Harris & Long, 1999; Kavanagh & Kennedy, 1992; Parveen et al., 2013; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2005; Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006). To date, little is known about the way in which culture underpins caregiver motivations and willingness to provide informal care, that is the question of how culture shapes motivations, not only if it does, needs to be addressed.

This meta-ethnography aims to

• identify potential explanations for how culture underlies motivations and willingness to provide care,

• explicate the possible interactions between ethnocultural factors,

• develop a model that explains cultural determinants of motivations and willingness to provide care.

We seek such explanations to inform culturally appropriate support for caregivers and their care recipients.

Methods

A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring motivations and willingness to care was completed (Zarzycki, Morrison, et al., 2022), from which studies describing cultural motivations in their findings were purposively selected for this meta-ethnographic synthesis. The goal of meta-ethnography is to systematically synthesise a body of qualitative research to create a ‘whole’ greater than the sum of its parts, offering new conceptual insights whilst preserving the ideas from the original studies. We followed the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre guidance (EPPI-Centre, 2010; Gough et al., 2017) and meta-ethnographic guidelines – Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnographic approach (Noblit & Hare, 1988) and its updates (Britten & Pope, 2012; Britten et al., 2002; France, Cunningham, et al., 2019; Toye et al., 2014). Meta-ethnography has been successfully applied to wide-ranging areas of health psychology and social care research (Campbell et al., 2011; Sarmento et al., 2017).

Eligibility Criteria

Included studies reported qualitative data on motivations and/or willingness to provide care that pertained to culture-specific norms of informal care provision amongst adults (aged 18 years and over) self-identifying as informal caregivers. Studies reported in English were included. No restrictions were applied to caregiver relationship type (e.g. spouse/non spouse), caregiver gender, care recipient’s age (only 18+ years), gender or diagnosis.

Identification of Studies

Search strategy

A preliminary search was undertaken applying free text terms and thesaurus terms partially used by a previous systematic review of the impact of motivations on caregiver outcomes (Quinn et al., 2010) as well as scoping searches. Additional scoping searches identified that the search terms used to describe ‘caregivers’, ‘motivations to provide care’ and ‘willingness to provide care’ were insufficiently sensitive (defined as the identification of as much evidence as possible; Gough et al., 2017) to capture all papers that related to these terms, with studies wrongly excluded because of their poor indexing. Given the need to include all relevant papers and sustain a balance between sensitivity and specificity, terms relating to the ‘caregiver’ (e.g. ‘spouse’, ‘relative’ or ‘family’), ‘motivations to provide care’ and ‘willingness to provide care’ (e.g. ‘obligation’ or ‘motives’) were also used even though this reduced specificity (defined as the precision of the search; Gough et al., 2017).

The systematic literature search examined papers published before 31st July 2019 using the following databases: MEDLINE via EBSCO, PsychInfo, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science.

The search terms were

- motivation, ‘motivations to care’, ‘motivations to provide care’, motive*, drive, oblig*, duty, filial,

- ‘willingness to care’, ‘willingness to provide care’, willing*,

- value*, ‘familism’, social, personal, ethnic*, cultural, demographic*, diagnosis, illness, characteristic*, determinant*,

- caregiver*, spouse, partner, family, relative*, carer*, caregiving.

The S1 Supplemental File presents detailed search strategy commands applied within scientific databases.

A search of additional sources (e.g. unpublished and grey literature, ‘Google Scholar’, PhD dissertations) was conducted to ensure inclusivity/reduce any effects of publication bias. The specific additional sources used are appended within S1 Supplemental File.

Selection process

Titles and abstracts of search results were first screened by the principal researcher (MZ), with subsequent retrieval and review of potentially eligible full-text papers conducted by two reviewers (MZ, EB) who dual reviewed a sample of 20% to ensure consistent application of eligibility criteria and appropriate study classification.

Data extraction

Data were entered into standardised and comprehensive data extraction forms which included the country where the study was completed; study aims; research participants; research methods; main constructs from the conceptual framework, findings and authors’ conclusions. Schutz’s conceptualisation of second- and third-order constructs (Britten et al., 2002; Noblit & Hare, 1988) was applied (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of First-, Second- and Third-Order Constructs.

| Order | Definition |

|---|---|

| First-order construct | Caregivers’ descriptions of cultural motivations and willingness to provide care (as expressed in raw transcript excerpts) |

| Second-order construct | Original authors’ descriptions (as indicated by key themes, concepts and metaphors) of caregivers’ cultural motivations and willingness to provide care |

| Third-order construct | Reviewers’ descriptions (as indicated by key concepts and models developed) of caregivers’ cultural motivations and willingness to provide care |

Data synthesis

Data synthesis followed Noblit and Hare’s seven-step process of getting started; deciding what is relevant to the research questions; reading the studies; determining how studies are related; translating studies into one another; synthesising translations and expressing the synthesis (France, Uny, et al., 2019; Noblit & Hare, 1988).

In the first phase the conceptual data presented was thematically grouped (Britten & Pope, 2012; Britten et al., 2002; France, Cunningham, et al., 2019; Toye et al., 2014), preserving its context (first- and second-order constructs). When key concepts were determined and applied to the first study, the next study was synthesised using two types of translation processes (Britten et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 2003; France, Cunningham, et al., 2019) – reciprocal and refutational. Reciprocal translation refers to concepts across the studies which agree with each other and can be aggregated; refutational translation pertains to concepts across the studies which conflict with one another. The names of the sub-concepts and concepts were iteratively generated by reviewers reflecting meanings (rather than summary descriptions) discerned in the synthesised data. The translation synthesis process compared concepts individually, account by account (i.e. each account pertaining to each concept identified) in chronological order (i.e. study by study) as proposed by Campbell et al. (2003). The concepts were found to be congruent with one another. Table 2 (below) describe the contribution of the concepts to each of the studies included in this review.

Table 2.

Concepts and Sub-Concepts Present in Each of the Included Studies.

| Study Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Presence of the Concept Across Studies (%) per | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globerman (1996) | Yamamoto and Wallhagen (1997) | Sheu (1997) | Browne Sehy (1998) | Sasat (1998) | Harris and Long (1999) | Kao and Stuifbergen (1999) | Chao and Roth (2000) | Kim and Theis (2000) | Van Sjaak Geest (2002) | Jones et al. (2002) | Yeo et al. (2002) | Jones et al. (2003) | Ho et al. (2003) | Spitzer et al. (2003) | Mok et al. (2003) | Leichtentritt et al. (2004) | Holroyd (2005) | |||

| Cultural duty and beliefs of obligation | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 100% | |

| Gendered cultural expectations | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 52% | ||||||||

| Cultural values | Filial piety | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 57% | |||||||||

| Familism | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 54% | |||||||||

| Religious ideas | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 46% | ||||||||||

| Cultural identity | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 57% | |||||||||

| Love and emotional attachments | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 43% | ||||||||||

| Repayment motive | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 63% | ||||||

| Competing demands | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | 23% | ||||||||||||

Based on this congruence the first reviewer arranged (configured) concepts, second- and third-order constructs, to build up a ‘line of argument’, that is a ‘narration’ which provides an ‘explanation’ or ‘theory’ of the findings. The most compelling explanation formulated was then introduced to the wider review team who confirmed the explanation and the preservation of the meaning between the second-order constructs and the first reviewer’s third-order interpretations. 1

Quality and relevance appraisal

Each study was dual-assessed according to the three ‘Dimensions of Difference’ of Evidence Claims (Gough et al., 2017) with respect to

• methodological standards of the review (see PRISMA statement in online S1 Supplemental File),

• methodological standards of the included studies (see CASP qualitative checklist in online S1 Supplemental File; based on the Weight of Evidence Framework applied the studies could be awarded an assessment of high, medium or low),

• the quality of the evidence produced (GRADE-CERQual Qualitative Evidence Profile).

To sustain the highest quality of the meta-ethnographic review, the eMERGe meta-ethnography reporting guidance (France, Cunningham, et al., 2019) was applied (summarised in online S1 Supplemental File).

Findings

Search Results

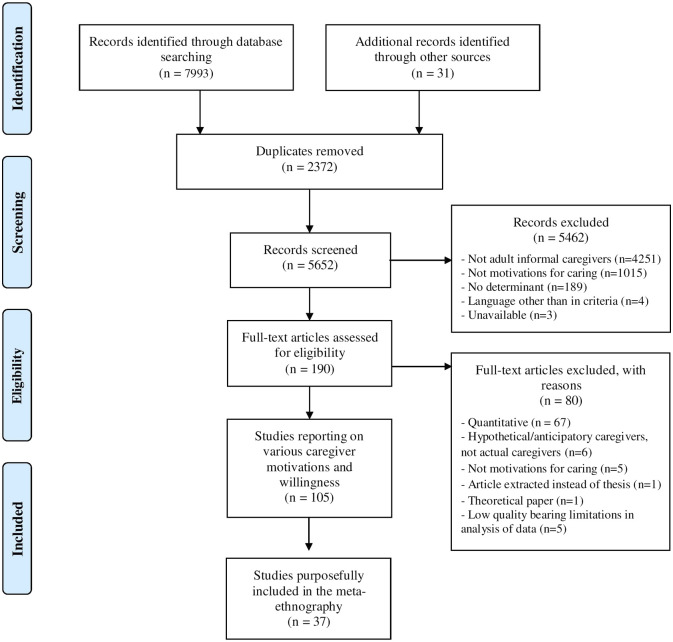

The PRISMA diagram summarises the search flow (Figure 1) for the systematic review with the main reasons for study exclusion. From an initial identification of 9793 papers, 105 were considered eligible studies for a review of diverse determinants of motivations and willingness to provide care (Zarzycki, Morrison, et al., 2022; Zarzycki, Seddon, et al., 2022). From these, 37 studies addressing culturally specific motivations for providing informal care were selected for the current meta-ethnographic synthesis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of included studies.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-Ethnography

Included articles from this point on are referred to by their ‘study number’, as indicated in Tables 2a & 2b. Studies are listed in chronological order.

A total sample of 833 caregivers participated in the included studies with one study focussing additionally on a document analysis pertaining to the nation-specific social policy on informal caregiving [31]. Most participants were of Asian ethnicity (N = 574; 68%), followed by Caucasian (N = 90; 11%), non-Caucasian American (N = 80; 10%); Black African (N = 71; 9%) and finally, Arab ethnicity, the smallest ethnic group within the studies synthesised (N = 18; 2%). Many of the studies (N = 33, 89%) included mixed caregiving relationship types, but the most common relationship types were adult children (including daughters-in-law) and spouses.

Only four studies [4,19,23,29] were longitudinal in design. The authors of one study did not specify the research design [24], that is data collection was not described in detail.

Amongst the included studies, 21 (57%) were judged to be of high quality (i.e. they had no or very minor methodological concerns) [1,3,4,8,11,13,14,16–18,20,22,23,28,29,32,34–37], whereas 16 (43%) were judged to be of moderate quality [2,5–7,9,10,12,15,19,21,24,26,27,30,31,33]. No study was judged to be of low methodological quality.

Further characteristics of the included studies such as the setting, methods of data collection and analysis are provided in the online S1 and S2 Supplemental Files.

Meta-Ethnography Study Findings

Six main concepts were identified, including cultural self-identity, which was an overarching concept, that is positioned in the centre of the developed line of argument (see below the meta-ethnographic model); cultural duty and obligation; cultural values; love and emotional attachments; repayment and reciprocity; and competing demands and roles. Online supplementary meta-ethnography grids (see S1 Supplemental File) show the most illustrative statements for each concept/sub-concept.

The generated concepts were interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Firstly, the six above-mentioned concepts are presented separately, beginning with the overarching concept of cultural self-identity and ending with competing demands and roles. Subsequently, the model of cultural underpinnings of caregiving motivations is presented to provide an overall integrated explanation of the concepts and the interactions between them.

Table 2 shows the concepts and sub-concepts present in each of the included studies.

1. Cultural self-identity

The term ‘cultural self-identity’ refers to a caregiver’s identity informed by their cultural background. 2 Caregiving was seen to become an important part of an individual’s self-identity [15,16,33,34,36], either expressed directly by study authors with a reference to identity [16] or implicitly referred to as an ‘internalisation’ of the caregiving role [18]. Cultural self-identity was shaped by cultural socialisation, for example earlier role modelling by the person’s relatives in caring for family members before that person themselves became a caregiver [11,34,35]. This was informed by cultural values and norms (e.g. the values of Confucianism in Asia) [3,6,21,22,25,29,31,34], as described below (see the concept ‘cultural values’ below). These cultural values relating to caregiving were conveyed to individuals through different channels of socialisation, for example observing other family members carrying out caregiving duties. Given that the cultural self-identity of the future caregiver was shaped in socialisation, informal care was often an expected part of an individual’s life [2,14,19,37]. For instance filial caregiving was an expected ‘career’ for Japanese caregivers, brought up with an expectation that either an unmarried adult son or – if married – his wife (daughter-in-law) will need to provide care to their parents when such need arises. As such, social embeddedness of filial caregiving was taken for granted and cultural norms upheld it [19], providing a sense of preparedness and expectedness (anticipation) of the role [2,14].

Whilst consideration of the impact that cultural self-identity may have on caregiving motivations was absent in 43% of included studies (Table 2), the synthesis clearly depicted – in our view – cultural self-identity as mediating between (i) the values one holds as well as the sociocultural norms to which one conforms (see the concept ‘cultural values’ below) and (ii) the sense of obligation and responsibility (see the concept ‘cultural duty and obligation’ below). The last section of findings describes the meta-ethnographic line of argument presenting in detail the mediating role of the cultural self-identity.

2. Cultural duty and obligation

The concept of obligation was identified in all studies as an overriding motivation for caregiving. The terms cultural duty and obligation were used interchangeably in first- and second-order data, and referred to cultural norms of appropriate and desired caregiving behaviours, which were rooted in cultural norms, societal norms, gender norms, religious beliefs and philosophical beliefs [3,5–8,10,18,20,24,33,37].

The concept of gendered cultural expectations evidences the perception of informal caregiving as primarily a women’s domain, categorised here as a sub-concept of cultural duty and obligations [1,2,5,6,8,10,12,15,17,18,22,24,27,28,33,34]. Gendered expectations played an important role in caregiver socialisation [1,29], shaping cultural identity and motivations to assume the role and to continue providing care. For example Donovan and Williams [29] showed that informal caregiving comprised part of women’s self-identity, that is being a Vietnamese woman implies the provision of care to family member(s). Importantly in this culture, there is no distinction between the role of a caregiver and the role of a woman.

Cultural duty and obligation were upheld by social expectations (e.g. caregiving viewed as a ‘virtuous deed’ in some Asian cultures) [23,27], legal obligation [31] and could be modified by situational factors, for example the presence/absence of alternative care arrangements [28,32]. The cultural value system underpinned cultural norms and was positioned as a distal influence implicitly underpinning a sense of duty and obligation [3,11–14,17,26,30,35,36].

3. Cultural values

Cultural values comprised of three sub-concepts of filial piety, familism (familial loyalty and solidarity) and religious and philosophical ideas which oriented around perceived cultural norms and underpinned the caregivers’ perceived duty and obligation to provide care.

3.1 Filial piety

Filial piety, defined in lay language as respect for parents and the family elderly, was understood as a traditional cultural norm which elicits personal expectations for caregiving amongst adult child caregivers caring for a parent. Discerned as a cultural value, filial piety posits an ‘inevitable responsibility’ on adults to provide care to their parents [8]. This value was a distal and essential factor impacting caregiver motivations in other samples, that is not only parent caregivers [3,8,14,22,23,32].

3.2 Familism, familial loyalty and solidarity

The cultural value of familism is seen in the second-order constructs that referred to ‘strong identification and attachment of individuals with their families (nuclear and extended) and strong feelings of loyalty, reciprocity and solidarity among members of the same family’ (Sabogal et al., 1987, p. 397–398). Familism was often implicitly (seen mainly in second-order constructs) expressed as a belief that care ought to be provided by family and family alone, and familial caregiving was seen as being ‘loyal’ to the family [14,15,23]. The value of familism was also incorporated into the cultural self-identity of caregivers and thus comprised an essential factor impacting overall motivations and willingness to provide care [5,7,12,14–17,23–25,27,30,33,35], as demonstrated above (the concept of ‘cultural self-identity’).

3.3 Religious and philosophical ideas

For some, religious ideas motivated the provision of informal care and/or were viewed as underpinning culturally bound obligation or responsibility [14,25]. For example Confucianism in Asia highlighted the significance of filial piety, familial relationships or respect for older people and determined caregivers’ values and belief systems [27]. Religious and philosophical ideas, incorporated in, and affirming cultural values of informal care provision, comprised a key determinant of personal and familial obligations to provide care [31].

4. Love and emotional attachments

We can distinguish between behavioural expressions of love, and love and attachment expressed as an emotional response to the care recipient. Both were identifiable motives for assuming the caregiving role and for continued caregiving, that is caregiving provides the opportunity to demonstrate love behaviourally or emotionally. The former constituted an explicit way of showing love and affection to the care recipient as prescribed by sociocultural norms and expectations, for example caring behaviour informed by filial piety or other cultural values [3,16,29,32,34]. The latter referred to emotional attachments, the feelings of love or affection as motivators to start and to continue providing informal care [2,4,6,10,11,22,25,30,36].

5. Repayment and reciprocity

The sense of reciprocity or duty to reciprocate the care and/or love the caregivers had previously received from care recipients was found to be important and based on mutual obligations or a desire to repay by fulfilling the caring duty [2–4,8,11,12,16,17,19,20,22,30,35–37]. Repayment was informed either by cultural norms, for example the care recipient’s previous conduct toward members of the community was a prerequisite for receiving informal care amongst rural Africans in Ghana [10], or repayment derived from cultural values and religious beliefs [5,18,27,33,34], for example underpinned by a Confucian sense of duty [18] or a way to gain blessings of prosperity from supernatural forces [27].

6. Competing demands and roles

Four main factors comprising demands competing with caregiving duties were identified: competing demands relating to a caregivers’ increased contribution to the labour market; the perceived and actual demands of paid employment; employment migration and variable access to/costs of alternative care and support to enable caregivers continued paid employment [2,9,15, 17, 27, 41]. These influenced motivations and willingness to initially provide care and to continue caring, in negative ways. We found no evidence in the literature to suggest these factors impact positively on motivations to care.

The competing multiple roles that some caregivers occupied [7,11] negatively influenced their motivations and willingness to initiate or continue caregiving [3,32]. In two studies [9, 15] it was noted that employers did not offer flexible working hours, supplemental health insurance or family benefits which made it difficult for some caregivers to combine their caregiving role with paid employment. This highlights the importance of flexible employment policies and practices (e.g. flexible hours). More flexible work practices increase the likelihood of a person being able to combine caregiving and paid employment (Bainbridge & Townsend, 2020; Longacre et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2018).

Identity inconsistency can be discerned in the light of caregiver conflicts between competing identities, for instance between being a caregiver, mother/father, daughter/son, wife/husband and employee. Identity inconsistency may result in stress or initiate a transition to a different role (e.g. relinquishing employment; Stryker & Burke, 2000) or renegotiation of cultural values and norms (e.g. a caregiver of the opposite sex to the care recipient provides informal care which was previously considered culturally inappropriate and unacceptable to both [20]).

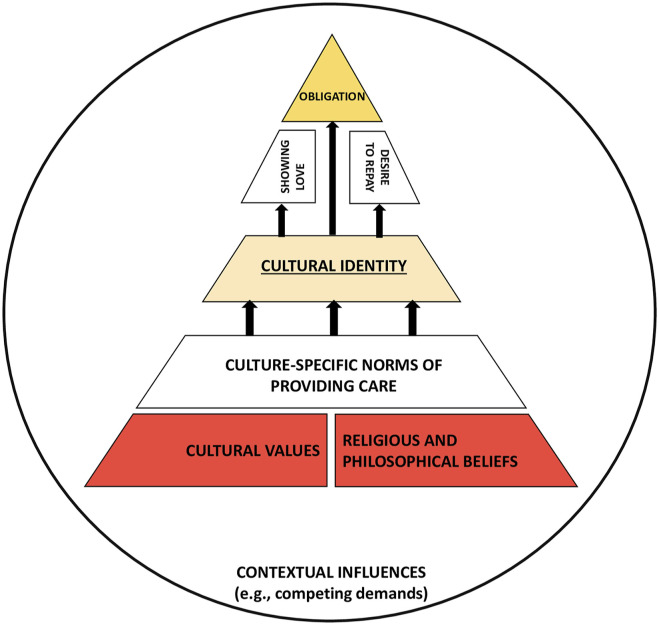

Model Depicting Cultural Underpinnings of Motivations to Provide Care

The concepts (1–6) described above informed a meta-ethnographic line of argument, explaining how cultural norms and values influenced overall motivations to provide care (see pyramid chart – Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A meta-ethnography pyramid chart with a line of argument.

The model posits that explicit personal motives pertaining to the sense of cultural duty and obligation to provide care (2), the expression of love and emotional attachments (4) and the desire to repay/reciprocate the care recipient (5), constructed during socialisation, are sustained by distal but underpinning factors, that is the caregiver’s cultural self-identity (1) and the culture-specific care norms and cultural values (3) (filial piety, familism, and religious and philosophical beliefs); and balanced against potential barriers created by competing demands (6). The perceived cultural duty and obligation to provide care (2), described as the overriding motivation for caregiving, is strongly determined by cultural factors such as cultural values (3) which were mainly described as implicit, latent factors [3,5,23–25,27,30–33,7,8,12,14–17,22], positioned as distal influences on motivations to provide care (see Figure 2).

The proposed model of the cultural underpinnings of motivations for providing informal care posits that the sense of obligation (2), constructed during socialisation, is sustained by the caregiver cultural self-identity (1). The sense of obligation (2), combined with the expression of love/emotional attachments (4) as well as a desire to repay the care recipient (5) are informed by culture-specific norms of providing care and cultural values encompassing the values of filial piety and familism, and religious/philosophical beliefs (3). The meta-ethnographic line of argument highlights the crucial role of cultural identity in caregiver motivations and willingness to provide care that connects all identified concepts. Cultural self-identity (1) is positioned as a central, overarching concept which translates the foundational motives of culture-specific care norms and values (3) into explicit caregiving motivations (2, 4, 5). The sustainability of these caregiving motivations is maintained to a large extent by caregiver self-identity as located and supported within a given culture(s). The model seeks to present how the conceptualised levels of identified determinants of caregiver motivations interact and build upon each other (as depicted in Figure 2).

Based on the model, it might be expected that future informal care provision would be secured by being strongly ingrained in culture, and cultural self-identity. However, key factors may modify the salience of culture in determining caregiver motivations: (a) the notion of perceived choice in undertaking the role, that is when considering caregiving duty and obligation; (b) competing demands, roles and identities; (c) the consideration of care home placement which demonstrated that cultural values can be negotiated (in one study [14]); (d) other contextual factors not discussed in the reviewed studies but seen in other studies of caregiver motivations (e.g. the stage and severity of a care recipient’s illness, caregiver’s life stage, family structure, geographical distance between the care recipient and caregiver; e.g. Bei et al., 2021). Additionally, even though cultural values around caregiving were strongly rooted and seen to have a vital role in shaping motivations for caregiving, the boundaries of understanding what caregiving should entail (as prescribed by the cultural values) may change in the face of transitions in the care recipient’s experience. For example admission to a care home may offer the caregiver a different way of caring for someone rather than an opportunity to relinquish the caregiving role.

Discussion

This review brings together studies conducted over two decades in a wide range of countries and cultures. Data synthesis generated multiple motivations for caregiving with six main concepts identified: cultural self-identity (described as an overarching concept); cultural duty and obligation; cultural values; love and emotional attachments; repayment and reciprocity; and competing demands and roles. We are not aware of any similar review aiming to understand how culture-specific determinants shape caregiver motivations and willingness to provide care although this has previously been called for (Greenwood & Smith, 2019; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2005; Quinn et al., 2010).

The model developed as a meta-ethnographic ‘line of argument’ offers a novel and informative explanation, depicting the levels at which the identified cultural determinants (concepts) affect motivations and willingness to provide care. Cultural self-identity is central for the model, framing people’s understanding of the social and physical world and their role in it, pervading different aspects of the caregiver’s life (Unger, 2011) and including caregiving motivations, namely obligation to provide care, expression of love and a desire to reciprocate care. Cultural self-identity is a psychological construct which translates cultural values, religious and philosophical beliefs, and cultural norms into a sense of caregiving obligation, regulating the expression of love and a need for repayment to the care recipient.

Reflecting on the implications of our findings for key frameworks and theories, we acknowledge Geertz’s (1973) theoretical conceptualisation of culture as ‘a set of control mechanisms’. Although this appears confirmed by this ethnographic review we would place more emphasis on the concept of self-identity, in which control mechanisms are internalised and regulated, than on the processes of socialisation (Geertz, 1973) or inherent social expectations. We suggest that it is the sense of cultural self-identity that translates cultural values and received norms into conscious caregiving motivations. The evidence also supports the significance of contextual circumstances that limit a person’s ability to model the cultural ideal (Geertz, 1973) – in this instance, competing demands within a caregiver’s life influence the processes of negotiating their caring role, seen in relation to conflicting identities and not only conflicting values.

The evidence presented is related to existing theories of self-identity. The concept of self-identity defines who or what an individual is. Tracing back to the pioneers of self-identity theory, that is James (1890) and Mead (1934), we focus on the caregiving-identity relationship in the context of culture and ethnicity. In James’s theory of self, the self is conceptualised to consist of both the known (the Me) and the knower (the I – described as the agent, thinker, and knower). The Me, comprises mental representations that people have of themselves (e.g. a kind person, a woman, a lawyer). James’s distinction between ‘the Me’ and ‘the I’ proved to be a powerful springboard for subsequent identity theorists (Stets & Serpe, 2013) and empirical research (e.g. Buse & Twigg, 2014). On psychological grounds, generally, an identity is considered to be a construct that defines individuals: in particular roles in society (e.g. parent, spouse); in specific groups in society (e.g. family, a church); and in specific personal characteristics that make them unique from others (e.g. an intelligent person). This conceptualisation derives from James’s concept of ‘the Me’, informing for instance the commonly applied self-categorisation theory (which distinguishes between personal, social and superordinate identities; Turner et al., 1987). Hence, people have multiple ‘me’? identities (Hughes et al., 2013; Stets & Serpe, 2013; Stryker & Burke, 2000), which may reinforce each other, for example when culture/cultural identity is incorporated into one own’s self-identity; or conflict with or shift in relationship to each other over time, for example incompatibility between the identities of caregiver and employee (see Huynh et al., 2011; Stryker & Burke, 2000). The only existing caregiver identity theory (Montgomery & Kosloski, 2009; Savundranayagam & Montgomery, 2010) conceptualises caregiving identity as a series of transitions emerging from the change of roles (e.g. a child becoming a carer for a parent, or a spouse becoming a carer for their partner). Although this work provides important theoretical grounds and empirical evidence in support of the importance of identity in informal care research, our review offers a cross-cultural exploration of the caregiver self-identity as a further crucial component shaping caregiver motivations. Whilst Montgomery and Kosloski (2009) particularly emphasise caregiving transitions in a person’s identity, our review highlights how cultural socialisation around, the sense of preparedness for caregiving, influence caregivers’ motivations for caring independent of any transitions. It should be acknowledged however that due to acculturation and globalisation processes, any pre-existing understanding of informal care provision may be renegotiated and restructured (e.g. Han et al., 2008; Kodwo-Nyameazea & Nguyen, 2008). For example caregiving may be less expected of children in the future, with alternative caring arrangements becoming more common (e.g. nursing home placements, paid care workers supporting people living in their own homes).

Cultural self-identity may influence people’s decisions about their caregiving behaviours, including motivations and willingness for caregiving (Unger, 2011). Studies outside the caregiving context have confirmed the effect of internalised cultural values on people’s decisions about health-related behaviours (Hammond, 2009; Hsia & Spruijt-Metz, 2008; Tsai et al., 2008; Unger, 2011). Our meta-ethnographic review has generated a theoretical model for how cultural self-identity may affect motivations to provide care and this model may hold implications for the actual exchange of care. However, this needs testing empirically, with further investigation of how the cultural self-identity influences motivations and willingness to provide care and influences caregiver behaviour over time.

Our findings demonstrate that people’s motivations for caring are underpinned by specific cultural values, religious and philosophical beliefs, and cultural norms of informal care provision and as such they hold potential implications for culturally sensitive assessment, support planning and for service development. Caregiving, for some, can be a taken for granted activity whilst for others it is a source of pride and a behaviour congruent with important cultural values. It can also be resented as limiting an individuals’ ability to take up educational, employment and social opportunities, or as initiating role/identity conflicts. Our findings illustrated potential tensions between different caregiving motivations that were seen in the example of conflicting identities (see ‘competing demands and roles’; Jones et al., 2002; Kao & Stuifbergen, 1999). Caregiver motivations should not be taken for granted by professionals involved in assessment and support planning with caregivers and their families – even where there is a cultural expectation and/or an ability to provide care, the individual may feel unable, or choose not to. Moreover, we acknowledge that educational endeavours at a population level (e.g. early interventions at schools) may operate to address the profile, norms and expectations around informal caregiving, for instance by highlighting the value that informal caregiving holds for the society across all cultures (Ng & Indran, 2021); or by challenging gendered cultural expectations obliging women more than men to provide care through promotion of the ungendered provision of informal care.

As an example of positive change in practice, the ‘what matters conversation’ (Welsh Government, 2015) may offer space to explore issues such as culturally bound caregiving motivations. Our findings highlight the need for assessment and support planning to be underpinned by acknowledgement of cultural (and demographic) diversity amongst the caregiver population, revealed in the diverse factors influencing motivations and willingess to care as evidenced in this review. Policy makers and practitioners should be mindful that cultural norms may pressure women more than men into informal caregiving, and the presented findings show that caregiving is still commonly perceived to be a part of ‘women’s domain’ in many societies throughout the world (see the concept ‘cultural duty and obligation’), despite more flexible sharing of household tasks by women and men in Westernised societies (Hook, 2010). As evidenced by Carers UK (2021), 58% of caregivers in the United Kingdom are women and they are most likely to be providing care and most likely to be providing more hours of care. Dialogue and culturally sensitive support planning between caregivers, care recipients, health and social care practitioners is necessary to achieve positive impact and to facilitate personal wellbeing outcomes.

Services should be mindful of caregivers’ specific cultural values, beliefs and motivations and they should consider the need to challenge certain cultural beliefs that may negatively impact upon caregivers’ experiences and the caregiving relationship (e.g. that seeking support contravenes cultural expectations/is shameful). Here, we highlight the notion of services being sensitive to cultural factors underpinning caregiver motivations, not the issue of services tailoring support to various cultural motives as that may be practically challenging, unfeasible, or not in the caregivers’ best interests.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first meta-ethnographic review of cultural underpinnings of informal care provision. It combined both comprehensive and purposive sampling and included a large number of diverse studies with a focus on culture-specific motivations and willingness for caring. The evidence informed a model describing how ethnocultural factors shape motivations and willingness to provide informal care. The studies included in the review were of high or moderate methodological quality and we did not detect any associations between study quality and reported findings. We uncovered a wide range of data and possible motivators, noting that the most frequently reported motivations may not be the most salient for caregivers and, in our proposed model, layers differentiate between more implicit and more explicit caregiving motives. This addresses, at least partly, the often-invoked argument that caregivers may not consciously consider what motivates them to provide care (Greenwood & Smith, 2019). Through investigating both first-, second- and third-order constructs, we offer new insights into cultural motivations.

Qualitative articles provided the foundation for the presented results and their interpretation. Meta-ethnography enabled the generation of the ‘whole’ – a greater picture of cultural caregiving motivations to which the parts must be compared, rather than the sum of these parts as seen across individual study reports (France, Cunningham, et al., 2019; Noblit & Hare, 1988). The meta-ethnographic translation processes and their expression (in the concepts produced and in the ‘line of argument’ developed) allowed for the ‘whole’ to come forth, a whole reflected in all the parts (Britten et al., 2002). Through this synthesis we raised the data to a higher level of abstraction and untangled the complex processes between culture and motivations and willingness for providing care.

The interpretative nature of meta-ethnography does, however, have limitations. It strongly depends on the reviewers’ position in interpreting the evidence bearing in mind that each separate study by itself would not be sufficient to answer the review question. We did not identify other explanations although the line of argument presented was first discussed and agreed by the review team. We acknowledge alternative explanations might be possible. Furthermore, the construct of identity or self remains to a large extent a mystery for psychologists and philosophers and the secrets behind the question ‘Who am I?’ should be acknowledged as part of existential discourse. We referred to cultural self-identity as this emerged inductively in the synthesis of studies; we do highlight, however, that there may be other specific identities or patterns/aspects of identity (Gallagher, 2013) that should be taken into consideration and that could potentially enrich the findings. Further research is needed to address the impact identity may have on caregiver motivations and outcomes.

A further limitation is that most of the studies synthesised were cross-sectional making it impossible to speculate about changes in cultural motivations and willingness to care over time. As a consequence, we cannot differentiate between initial and continued caregiving motivations, a limitation previously noted in a qualitative systematic review of motivations specific to dementia caregiving (Greenwood & Smith, 2019). Studies typically refer to motivations in general making it impossible to confidently distinguish descriptions of initial motivations for caring from motivations for continuing to care. In the few cases where it was possible, findings describing why caregivers continued in their role were noted (Globerman, 1996; Han et al., 2008; Ho et al., 2003; Kietzman et al., 2013; Park, 2015; Sheu, 1997; Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006; Yamamoto & Wallhagen, 1997), and the synthesis elicited some specific inferred differences between initial motives and continued motives. For example, gendered cultural expectations were discerned as both a reason for initiating, and continuing the caregiving role whilst specific sociocultural expectations, such as primogeniture norms in Japan, regulated the initial decision to become a caregiver.

The primary studies explored cultural motivations and/or willingness of caregivers who were already in role and thus initial motives were inferred through retrospective accounts (first-order constructs, where available). For example, one cross-sectional study in Japan (Yamamoto & Wallhagen, 1997) clearly differentiated between an expectancy of daughters-in-law assuming the caregiving role due to sociocultural expectations and the crucial role of cultural values, caregiver self-identity, and emotional attachments for the continuation of the role. Typically, no second-order constructs referred to this distinction, and in fact most first- and second-order constructs tended not to highlight such changes in caregiver motivations and willingness, even the four included longitudinal studies (Browne Sehy, 1998; Donovan & Williams, 2015; Kong et al., 2010; Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006).

Identifying and distinguishing initial and continued motivations is further complicated by conceptual and methodological challenges. For example, the timeframe for becoming a caregiver is not always a discrete event but the role can emerge gradually making quantifiable distinction between initial and continuation motives a challenge. Furthermore, many factors likely impinge upon changes in caring motivations such as the nature, stage and severity of the care recipient’s illness, or the caregiver’s own health or life stage. Moreover, within the studies synthesised the reported length of time spent caring was heterogenous, making it impossible to compare motivations based on this characteristic. Future research should focus on the temporal nature of caregiving motivations, including whether there are indeed differences or similarities between initial and continued motivations. Similarly, further research is needed to understand why some caregivers relinquish their caring role.

Conclusion

This review describes how culture shapes informal caregiver motivations for caring. The concepts generated in the synthesis informed a model of cultural caregiving motivations in which caregiver cultural self-identity, the central concept, translates the foundational motives of culture-specific care norms and values into explicit caregiving motivations such as cultural duty and obligation, the expression of love toward the care recipient and a need to reciprocate previous care or love. The multi-domain model of cultural caregiving motivations holds implications for the actual exchange of care. Caregiver motivations should not be taken for granted by healthcare or social care professionals involved in assessment and support planning, educational endeavours at a population level may support caregiving through addressing the norms and expectations around informal care, and support should be sensitive to cultural caregiving motivations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for How Culture Shapes Informal Caregiver Motivations: A Meta-Ethnographic Review by Mikołaj Zarzycki, Diane Seddon, Eva Bei, Rachel Dekel, and Val Morrison in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material for How Culture Shapes Informal Caregiver Motivations: A Meta-Ethnographic Review by Mikołaj Zarzycki, Diane Seddon, Eva Bei, Rachel Dekel, and Val Morrison in Qualitative Health Research

Notes

Online S1 Supplemental File describes the analytic procedures of this meta-ethnography synthesis in more detail.

The term ‘cultural self-identity’ was applied rather than ‘cultural identity’ or ‘ethnic identity’. The latter usually refers to an individual’s ancestral geographic origin, whereas ‘cultural identity’ relates to culture(s) which is/are groups of people who share knowledge, beliefs, norms and behaviours (e.g. gay culture), but not necessarily the geographic origin (and thus ethnic identity may/may not be part of cultural identity; Unger, 2011). The term ‘cultural self-identity’ acknowledges that self-identity is formed as part of and informed by cultural identity, that is individual features of culture(s) is/are incorporated into the self-identity (Huynh et al., 2011), for instance caregiver’s self-identity (e.g. self-identified caregiver who sees themselves as influenced by Jewish culture and accordingly identifies as a Jewish caregiver/caregiver following Jewish cultural norms and expectations).

Author Contributions: MZ and VM designed the review. MZ and EB screened, extracted and critically appraised the data. MZ conducted and led the synthesis with EB being involved in reciprocal translations only. The processes were supervised by VM, DS and RD. MZ wrote the original manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by VM, DS and RD. All authors gave final approval to this manuscript.

Author Notes: This meta-ethnography was undertaken as part of postgraduate study conducted by author Mikołaj Zarzycki.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting online files.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The PhD was funded by EC funded Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network (H2020-MSCA-ITN-2018), grant agreement no. 814072. The funder has not had any role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Mikołaj Zarzycki https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8357-563X

Diane Seddon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0660-4839

Eva Bei https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3093-0829

Rachel Dekel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7082-0456

Val Morrison https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4308-8976

References

- Aranda M. P., Knight B. G. (1997). The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist, 37(3), 342–354. 10.1093/geront/37.3.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M., Wells B. (2000). Diversity within Latino families: New lessons for family social science. In Demo D., Allen K., Fine M. A. (Eds.), Handbook of family diversity (pp. 252–273). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge H. T. J., Townsend K. (2020). The effects of offering flexible work practices to employees with unpaid caregiving responsibilities for elderly or disabled family members. Human Resource Management, 59(5), 483–495. 10.1002/hrm.22007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bei E., Zarzycki M., Morrison V., Vilchinsky N. (2021). Motivations and willingness to provide care from a geographical distance, and the impact of distance care on caregivers’ mental and physical health: A mixed-method systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 11(7), 1–7. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A. (2019). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 7. Release Version: 7.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. 10.6103/SHARE.w7.700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E. H., Curry L. A., Mcgraw S. A., Webster T. R., Kasl S. V, Andersen R. (2004). Intended use of informal long-term care: The role of race and ethnicity. Ethnicity & Health, 9(1), 37–54. 10.1080/13557850410001673987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N., Campbell R., Pope C., Donovan J., Morgan M., Pill R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215. 10.1258/135581902320432732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N, Pope C. (2012). Medicine taking for asthma: A worked example of meta-ethnography (Hannes K., Lockwood C. (Eds.); pp. 41–58). Wiley-Blackwell BMJ Books. [Google Scholar]

- Browne Sehy Y. A. (1998). Moral decision-making by elderly women caregivers: A feminist perspective on justice and care. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge L., Winch S., Clavarino A. (2007). Reluctance to care. Cancer Nursing, 30(2), E9–E19. 10.1097/01.ncc.0000265298.17394.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse C., Twigg J. (2014). Women with dementia and their handbags: Negotiating identity, privacy and “home” through material culture. Journal of Aging Studies, 30(1), 14–22. 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camden A., Livingston G., Cooper C. (2011). Reasons why family members become carers and the outcome for the person with dementia: Results from the CARD study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(9), 1442–1450. 10.1017/S1041610211001189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Pound P., Morgan M., Daker-White G., Britten N., Pill R., Yardley L., Pope C., Donovan J. (2011). Evaluating meta-ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15(43), 1–164. 10.3310/hta15430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Pound P., Pope C., Britten N., Pill R., Morgan M., Donovan J. (2003). Evaluating meta-ethnography: A synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Social Science & Medicine, 56(4), 671–684. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carers UK (2021). State of caring 2021: A snapshot of unpaid care in the UK (pp. 1–28). http://www.carersuk.org/images/News__campaigns/CUK_State_of_Caring_2019_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (2010). EPPI-Centre methods for conducting systematic reviews. The Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, Social Research Institute, Faculty of Education and Society, University College London. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers B. (1996). Western and African conceptualizations of health. Psychology & Health, 12(1), 1–10. 10.1080/08870449608406915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao S. Y., Roth P. (2000). The experiences of Taiwanese women caring for parents-in-law. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(3), 631–638. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P., Brummett B. H., Goodwin P., Williams S. W., Williams R. B., Siegler I. C. (2005). Effect of race on cultural justifications for caregiving. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 60(5), 257. 10.1093/geronb/60.5.s257; http://ezproxy.bangor.ac.uk/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=106532500&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan R., Williams A. M. (2015). Care-giving as a Canadian-Vietnamese tradition: “It’s like eating, you just do it. Health and Social Care in the Community, 23(1), 79–87. 10.1111/hsc.12126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France E. F., Cunningham M., Ring N., Uny I., Duncan E. A. S., Jepson R. G., Maxwell M., Roberts R. J., Turley R. L., Booth A., Britten N., Flemming K., Gallagher I., Garside R., Hannes K., Lewin S., Noblit G. W., Pope C., Thomas J., Noyes J. (2019. a). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France E. F., Uny I., Ring N., Turley R. L., Maxwell M., Duncan E. A. S., Jepson R. G., Roberts R. J., Noyes J. (2019. b). A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases 11 medical and health sciences 1117 public health and health services. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1–18. 10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. (2013). A pattern theory of self. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 1–7. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Globerman J. (1996). Motivations to care: Daughters-and sons-in-law caring for relatives with Alzheimer’s disease. Family Relations, 45(1), 37–45. 10.2307/584768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gough D., Oliver S., Thomas J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N., Smith R. (2019). Motivations for being informal carers of people living with dementia: A systematic review of qualitative literature. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 169. 10.1186/s12877-019-1185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K. (2009). Global patterns of nicotine and tobacco consumption. In Henningfield J. E., London E., Pogun S. (Eds.), Nicotine psychopharmacology (pp. 3–28). Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. R., Choi Y. J., Kim M. T., Lee J. E., Kim K. B. (2008). Experiences and challenges of informal caregiving for Korean immigrants. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(5), 517–526. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04746.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. B., Long S. O. (1999). Husbands and sons in the United States and Japan: Cultural expectations and caregiving experiences. Journal of Aging Studies, 13(3), 241–267. 10.1016/S0890-4065(99)80096-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L., Tran J. N., Tran C., Hinton D. (2008). Religious and spiritual dimensions of the Vietnamese dementia caregiving experience. Hallym International Journal of Aging, 10(2), 139–160. 10.2190/HA.10.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho B., Friedland J., Rappolt S., Noh S. (2003). Caregiving for relatives with Alzheimer’s disease: Feelings of Chinese-Canadian women. Journal of Aging Studies, 17(3), 301–321. 10.1016/S0890-4065(03)00028-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd E. (2005). Developing a cultural model of caregiving obligations for elderly Chinese wives. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 27(4), 437–456. 10.1177/0193945905274907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook J. L. (2010). Gender inequality in the welfare state: Sex segregation in housework, 1965–2003. American Journal of Sociology, 115(5), 1480–1523. 10.1086/651384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia F.-N., Spruijt-Metz D. (2008). Gender differences in smoking and meanings of smoking in Asian-American college students. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(4), 459–463. 10.1177/1359105308088516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh K. H., Hu J., Clarke-Ekong S. (2008). Acculturation in filial practices among US Chinese caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 18(6), 775–785. 10.1177/1049732308318923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes N., Locock L., Ziebland S. (2013). Personal identity and the role of “carer” among relatives and friends of people with multiple sclerosis. Social Science & Medicine, 96, 78–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q.-L., Nguyen A.-M., Benet-Martinez V. (2011). Bicultural identity integration. In Schwartz S., Luyckx K., Vignoles V. (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 827–842). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ivey S. L., Laditka S. B., Price A. E., Tseng W., Beard R. L., Liu R., Fetterman D., Wu B., Logsdon R. G. (2013). Experiences and concerns of family caregivers providing support to people with dementia: A cross-cultural perspective. Dementia, 12(6), 806–820. 10.1177/1471301212446872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. (1890). The principles of psychology. Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. S., Zhang X. E., Jaceldo-Siegl K., Meleis A. I. (2002). Caregiving between two cultures: An integrative experience. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 202–209. 10.1177/10459602013003009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. S., Zhang X. E., Meleis A. I. (2003). Transforming vulnerability. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25(7), 835–853. 10.1177/0193945903256711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao H. F., Stuifbergen A. K. (1999). Family experiences related to the decision to institutionalize an elderly member in Taiwan: An exploratory study. Social Science & Medicine, 49(8), 1115–1123. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh K. H., Kennedy P. H. (1992). Promoting cultural diversity: Strategies for health care professionals. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kietzman K. G., Benjamin A. E., Matthias R. E. (2013). Whose choice? Self-determination and the motivations of paid family and friend caregivers. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 44(4), 519–540. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bangor.ac.uk/docview/1544981790?accountid=14874 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., Theis S. L. (2000). Korean American caregivers: Who are they? Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 11(4), 264–273. 10.1177/104365960001100404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B. G., Sayegh P. (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 65(1), 5–13. 10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodwo-Nyameazea Y., Nguyen P. V. (2008). Immigrants and long-distance elder care: An exploratory study. Ageing International, 32(4), 279–297. 10.1007/s12126-008-9013-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong E. H., Deatrick J. A., Evans L. K. (2010). The experiences of Korean immigrant caregivers of non-English-speaking older relatives with dementia in American nursing homes. Qualitative Health Research, 20(3), 319–329. 10.1177/1049732309354279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Lee J., Lee J.-E. (2019). Bereaved families’ experiences of end-of-life care at Home for older adults with non-cancer in South Korea. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 36(1), 42–53. 10.1080/07370016.2018.1554768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichtentritt R. D., Schwartz V., Rettig K. D. (2004). The lived experiences of Israeli Arab Moslems who are caring for a relative with cognitive decline. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 59(4), 363–389. 10.2190/YQAN-6KVA-7HPK-RX2C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longacre M. L., Weber-Raley L., Kent E. E. (2021). Cancer caregiving while employed: Caregiving roles, employment adjustments, employer assistance, and preferences for support. Journal of Cancer Education, 36(5), 920–932. 10.1007/s13187-019-01674-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A., Marquez-Gonzalez M., Knight B. G., Yanguas J., Sayegh P., Romero-Moreno R. (2010). Psychosocial factors and caregivers’ distress: Effects of familism and dysfunctional thoughts. Aging & Mental Health, 14(2), 193–202. 10.1080/13607860903167838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyonette C., Yardley L. (2003). The influence on carer wellbeing of motivations to care for older people and the relationship with the care recipient. Ageing and Society, 23(4), 487–506. 10.1017/S0144686X03001284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mead G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society (Vol. 111). Chicago University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck C., Anthony K. P. (2016). Marianismo and caregiving role beliefs among U.S.-Born and immigrant Mexican women. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 71(5), 926–935. 10.1093/geronb/gbv083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O. L., Nguyen K. H., Dao T. N., Vu P., Arean P., Hinton L. (2015). The sociocultural context of caregiving experiences for Vietnamese dementia family caregivers. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(3), 263–272. 10.1037/aap0000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok E., Chan F., Chan V., Yeung E. (2003). Family experience caring for terminally ill patients with cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nursing, 26(4), 267–275. http://ezproxy.bangor.ac.uk/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=106880188&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery R. J. V., Kosloski K. K. (2009). Caregiving as a process of changing identity: Implications for caregiver support. Generations, 33(1), 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Muoghalu C. O., Jegede S. A. (2010). The role of cultural practices and the family in the care for people living with HIV/AIDS among the Igbo of Anambra State, Nigeria. Social Work in Health Care, 49(10), 981–1006. 10.1080/00981389.2010.518885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng H. Y., Griva K., Lim H. A., Tan J. Y. S., Mahendran R. (2016). The burden of filial piety: A qualitative study on caregiving motivations amongst family caregivers of patients with cancer in Singapore. Psychology & Health, 31(11), 1293–1310. 10.1080/08870446.2016.1204450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng R., Indran N. (2021). Societal perceptions of caregivers linked to culture across 20 countries: Evidence from a 10-billion-word database. PLoS One, 16, 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblit G. W., Hare R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Park H. J. (2015). Legislating for filial piety: An indirect approach to promoting family support and responsibility for older people in Korea. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 27(3), 280–293. 10.1080/08959420.2015.1024536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. (2012). Filial piety and parental responsibility: An interpretive phenomenological study of family caregiving for a person with mental illness among Korean immigrants. BMC Nursing, 11(1), 28–35. 10.1186/1472-6955-11-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen S., Morrison V., Robinson C. A. (2011). Ethnic variations in the caregiver role: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(6), 862–872. 10.1177/1359105310392416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen S., Morrison V., Robinson C. A. (2013). Ethnicity, familism and willingness to care: Important influences on caregiver mood? Aging & Mental Health, 17(1), 115–124. 10.1080/13607863.2012.717251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sorensen S. (2005). Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist, 45(1), 90–106. 10.1093/geront/45.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadir F., Gulzar W., Haqqani S., Khalid A. (2013). A pilot study examining the awareness, attitude, and burden of informal caregivers of patients with dementia. Care Management Journals, 14(4), 230–240. 10.1891/1521-0987.14.4.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Sit J. W. H., Koo F. K. (2018). The influence of Chinese culture on family caregivers of stroke survivors: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1–2), e309–e319. 10.1111/jocn.13947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C., Clare L., Woods R. T. (2010). The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 43–55. 10.1017/S1041610209990810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson T., Griva K., Luszczynska A., Morrison V., Panagopoulou E., Vilchinsky N., Hagedoorn M. (2016). Caregiving in the illness context. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr M. K., Lang F. R. (2016). The role of anticipated gains and losses on preferences about future caregiving. Journals of Gerontology - Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(3), 405–414. 10.1093/geronb/gbu145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F., Marín G., Otero-Sabogal R., Marín B. V., Perez-Stable E. J. (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), 397–412. 10.1177/07399863870094003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento V. P., Gysels M., Higginson I. J., Gomes B. (2017). Home palliative care works: But how? A meta-ethnography of the experiences of patients and family caregivers. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 7(4), 390–403. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasat S. (1998). Caring for dementia in Thailand: A study of family care for demented elderly relatives in Thai Buddhist society. University of Hull. [Google Scholar]

- Savundranayagam M. Y., Montgomery R. J. V. (2010). Impact of role discrepancies on caregiver burden among spouses. Research on Ageing, 32(2), 175–199. 10.1177/0164027509351473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu S. (1997). Filial piety (Hsiao) and filial caregiving experiences of Chinese families in the San Francisco Bay area. University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer D., Neufeld A., Harrison M., Hughes K., Stewart M. (2003). Caregiving in transnational context: “My wings have been cut; where can I fly?” Gender and Society, 17(2), 267–286. 10.1177/0891243202250832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stets J. E., Serpe R. T. (2013). Identity theory. In Handbook of pocial psychology (pp. 31–60). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S., Burke P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297. 10.2307/2695840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toye F., Seers K., Allcock N., Briggs M., Carr E., Barker K. (2014). Meta-ethnography 25 years on: Challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 1–14. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y.-W., Tsai T.-I., Yang C.-L., Kuo K. N. (2008). Gender differences in smoking behaviors in an Asian population. Journal of Women’s Health, 17(6), 971–978. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. C., Hogg M. A., Oakes P. J., Reicher S. D., Wetherell M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. In Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B. (2011). Cultural identity and public health. In Schwartz S., Luyckx K., Vignoles V. (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 811–825). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sjaak Geest D. E. R. (2002). Respect and reciprocity: Care of elderly people in rural Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 17(1), 3–31. 10.1023/A:1014843004627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel N., Francke A. L., Kayan-Acun E., LJM Devillé W., van Grondelle N. J., Blom M. M. (2016). Family care for immigrants with dementia: The perspectives of female family carers living in The Netherlands. Dementia, 15(1), 69–84. 10.1177/1471301213517703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen M. I., Yamamoto-Mitani N. (2006). The meaning of family caregiving in Japan and the United States: A qualitative comparative study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(1), 65–73. http://ezproxy.bangor.ac.uk/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=106325259&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-N., Hsu W.-C., Yang P.-S., Yao G., Chiu Y.-C., Chen S.-T., Huang T.-H., Shyu Y.-I. L. (2018). Caregiving demands, job demands, and health outcomes for employed family caregivers of older adults with dementia: Structural equation modeling. Geriatric Nursing, 39(6), 676–682. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Government (2015). Social services and well-being (Wales) Act 2014 Part 3 code of practice (assessing the needs of individuals). [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N., Wallhagen M. I. (1997). The continuation of family caregiving in Japan. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(2), 164–176. 10.2307/2955423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G., UyenTran J. N., Hikoyeda N., Hinton L. (2002). Conceptions of dementia among Vietnamese American caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 36(1–2), 131–152. 10.1300/J083v36n01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu H. C., Zang Y., Chew J. H. S., Chau J. P. C. (2021). The influence of confucianism on the perceptions and process of caring among family caregivers of persons with dementia: A qualitative study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 32(2), 153–160. 10.1177/1043659620905891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki M., Morrison V., Bei E., Seddon D. (2022. a). Cultural and societal motivations for being informal caregivers: A qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Health Psychology Review. Online ahead of print 10.1080/17437199.2022.2032259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki M., Seddon D., Bei E., Morrison V. (2022. b). Why do they care? A qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis of personal and relational motivations for providing informal care. Health Psychology Review, 1–33. Online ahead of print 10.1080/17437199.2022.2058581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lee D. T. F. (2019). Meaning in stroke family caregiving in China: A phenomenological study. Journal of Family Nursing, 25(2), 260–286. 10.1177/1074840719841359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann K. A. (2015). What is culture? Definition of culture. Live Science Contributor. http://www.livescience.com/21478-what-is-culture-definitionof-%0Dculture.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for How Culture Shapes Informal Caregiver Motivations: A Meta-Ethnographic Review by Mikołaj Zarzycki, Diane Seddon, Eva Bei, Rachel Dekel, and Val Morrison in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material for How Culture Shapes Informal Caregiver Motivations: A Meta-Ethnographic Review by Mikołaj Zarzycki, Diane Seddon, Eva Bei, Rachel Dekel, and Val Morrison in Qualitative Health Research