Abstract

Multivalent antigen display is a well-established principle to enhance humoral immunity. Protein-based virus-like particles (VLPs) are commonly used to spatially organize antigens. However, protein-based VLPs are limited in their ability to control valency on fixed scaffold geometries and are thymus-dependent antigens that elicit neutralizing B cell memory themselves, which can distract immune responses. Here, we investigated DNA origami as an alternative material for multivalent antigen display in vivo, applied to the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV2 that is the primary antigenic target of neutralizing antibody responses. Icosahedral DNA-VLPs elicited neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in a valency-dependent manner following sequential immunization in mice, quantified by pseudo- and live-virus neutralization assays. Further, induction of B cell memory against the RBD required T cell help, but the immune sera did not contain boosted, class-switched antibodies against the DNA scaffold. This contrasted with protein-based VLP display of the RBD that elicited B cell memory against both the target antigen and the scaffold. Thus, DNA-based VLPs enhance target antigen immunogenicity without generating off-target, scaffold-directed immune memory, thereby offering a potentially important alternative material for particulate vaccine design.

Introduction

Multivalent display of antigens on virus-like particles (VLPs) can markedly improve the immunogenicity of subunit vaccines1–3. Nanoparticulate vaccines with diameters between 20 and 200 nm ensure efficient trafficking to secondary lymphoid organs, and particle diameters below 50 nm mitigate undesired retention at the injection site and promote the penetration of B cell follicles4,5. In secondary lymphoid organs, multivalency promotes B cell receptor (BCR) crosslinking and signaling as well as BCR-mediated antigen uptake, thereby driving B cell activation and humoral immunity6–13.

The importance of BCR signaling for the generation of antibody responses was initially recognized for thymus-independent (TI) antigens, particularly of the TI-2 class14–16. The multivalent display of these non-protein antigens induces BCR crosslinking in the absence of T cell help. The resultant antibody responses proceed through extrafollicular B cell pathways, with limited germinal center (GC) reactions, affinity maturation, and induction of B cell memory17,18. Multivalent antigen display also enhances BCR-mediated responses to thymus-dependent (TD) antigens, namely proteins8,9. In this context, follicular T cell help enables GC reactions to generate affinity-matured B cell memory that can be boosted or recalled upon antigen reexposure19–21. Consequently, the nanoscale organization of antigens represents a well-established vaccine design principle not only for TI antigens, but also to elicit humoral immunity through the TD pathway1–3.

Leveraging this design principle, protein-based virus-like particles (P-VLPs) have emerged as an important material platform for multivalent subunit vaccines22–38. P-VLPs enable the rigid display of TD antigens and have been used to investigate the impact of valency on B cell activation in vivo, suggesting early B cell activation and downstream humoral immune responses are improved substantially for some antigens as valency increases8–10. However, control over antigen valency in P-VLPs is constrained to the constituent self-assembled protein scaffold subunits, rendering the investigation of antigen valency on humoral immunity challenging without simultaneously altering scaffold size, geometry, and protein composition9,10. Alternatively, if a constant protein scaffold geometry is used, then current approaches are limited to stochastically-controlled antigen valency and spatial positioning8,29,30,38. Further, protein-based scaffolds are TD antigens that elicit humoral immunity themselves38–40. This potentially distracts antibody responses from the target antigens of interest41,42, and might also lead to immune imprinting43 or original antigenic sin (OAS)44,45 in which off-target, immunodominant epitopes distract from target epitopes of interest in generating B cell memory. Finally, scaffold-directed immunological memory may also result in antibody-dependent clearance of the vaccine material, thereby limiting sequential or diversified immunizations with a given P-VLP46,47.

To overcome these limitations of protein-based materials, here we sought to design rigid, TI scaffolds of fixed geometry and size to display target TD antigens of varying valency. Fixing scaffold geometry would isolate the impact of valency on promoting antibody responses, whereas use of a TI scaffold would promote focusing of the antibody response on the target, TD antigen of interest while confining scaffold-directed B cell responses to the non-boostable, TI pathway that is devoid of immunological memory48,49. This approach may therefore avoid the off-target, distracting antibody responses that affect P-VLPs40,50 while retaining the ability to enhance humoral immunity through multivalent antigen display. Wireframe DNA origami provides unique access to such rationally designed VLPs of the optimal 50 nm size-scale, with scaffold-independent control over valency of antigen display51–56. While we and others have leveraged this DNA-based material platform in vitro to probe the nanoscale parameters of IgM recognition57 and BCR signaling in reporter B cell lines58, the functional properties of this material remained to be investigated in vivo where complex processes including particle trafficking, T cell help, and scaffold degradation mediated by endonucleases are present.

To investigate the ability of these materials to elicit functional immune responses in vivo, DNA-VLPs functionalized with the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) derived from the spike glycoprotein, a key target for eliciting neutralizing antibodies against the virus59–62, were fabricated with varying valency, validated in vitro, and subsequently evaluated in vivo. This nanoparticulate vaccine displayed enhanced binding to ACE2-expressing cells in vitro, and induced BCR signaling in a valency-dependent manner in vitro consistent with previous findings58,63,64. Following sequential vaccine immunizations in mice, we observed valency-dependent enhancement of RBD-specific IgG responses and B cell memory recall in vivo using this DNA-based scaffold material. Functionally, neutralization of the wildtype, Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2 was found to be more efficient for antibodies elicited by DNA-VLPs compared with those elicited by monomeric RBD alone. However, immunized sera did not contain boosted, DNA-specific antibodies, and antibody enhancement was not observed in Tcra–/– mice, demonstrating that boosting of RBD-specific antibodies went through the TD pathway even though antigens were presented on TI scaffolds. This contrasted with a commonly used protein-based vaccine scaffold that generated and boosted specific B cell memory to both the target, RBD antigen, and the scaffold protein material. Taken together, our findings suggest that DNA origami-based materials can be used to enhance humoral immunity in vivo using multivalent antigen display via focusing of antibody responses on target antigens without the generation of distracting B cell memory against the VLP scaffold itself.

Results and Discussion

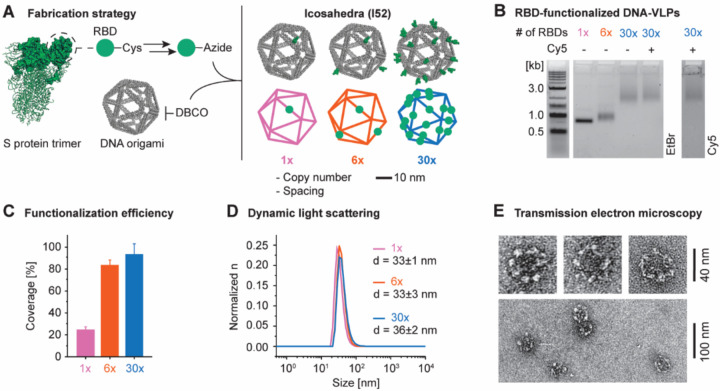

SARS-CoV-2 displays trimeric spike glycoproteins on a ~100 nm diameter scaffold65, where each glycoprotein monomer contains the receptor-binding domain (RBD) for engaging the ACE2 receptor mediating viral uptake, thereby rendering RBD a key target for neutralizing antibody responses59–62. To ensure optimal trafficking of our vaccine platform, which requires particle diameters smaller than 50 nm5, we computationally designed and fabricated an icosahedral DNA-VLP with 30 conjugation sites and approximately 34 nm scaffold diameter to display the RBD52,54. A covalent in situ functionalization strategy employing strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) chemistry was used to ensure rigid, irreversible antigen attachment to the DNA scaffold (Figure 1A)53, unlike previous work that used a reversible, hybridization strategy58. Towards this end, we synthesized 30 oligonucleotide staples bearing triethylene glycol (TEG)-DBCO groups at their 5’ ends to assemble DNA-VLPs symmetrically displaying 1x, 6x or 30x DBCO groups on their exterior (Figure S1, Table S1 to S3). Employing a reoxidation strategy, the monomeric RBD was selectively modified at an engineered C-terminal Cys with an SMCC-TEG-azide linker to yield RBD-Az which was subsequently incubated with DBCO-bearing DNA origami to fabricate I52–1x, −6x, and −30x (Figures 1B and S2, Note S1). The optimization of reaction conditions yielded near-quantitative functionalization efficiency of conjugation sites as determined by denaturing, reversed-phase HPLC53 and Trp fluorescence58 (Figures 1C and S3). The monodispersity of purified DNA-VLPs was validated by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 1D). Analysis of I52–30x via negative-strain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) validated structural integrity of the DNA origami with the desired total size of approximately 45 nm (Figure 1E and S4). While the icosahedral geometry could not be fully resolved, presumably due to accumulation of uranyl formate in the interior of the DNA origami, antigens were clearly visible and organized symmetrically.

Figure 1. Design and synthesis of DNA-VLPs covalently displaying the SARS-CoV-2 RBD.

(A) Recombinant RBD bearing an additional Cys residue at the C-terminus was expressed. The C-terminal Cys was selectively labeled with and SMCC-TEG-azide linker and subsequently conjugated to DBCO-bearing DNA-VLPs. The icosahedral DNA origami objects of approximately 50 nm diameter displaying 1, 6 and 30 copies of the RBD were fabricated. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) shows the gel shift due to increasing RBD copy number as well as low polydispersity of the VLPs samples after purification. An additional VLP bearing 5 copies of Cy5 was produced for ACE2-binding flow cytometry experiments. (C) The coverage of the DNA-VLPs with RBD was quantified via Trp fluorescence. (D) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to assess the dispersity of functionalized VLP samples. Representative histograms are shown. (E) Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) of I52–30x were obtained by negative staining using 2% uranyl formate and validate the symmetric nanoscale organization of antigens. Coverage values were determined from n = 3 biological replicates for I52–1x and from n = 6 biological replicates for I52–6x and I52–30x. Diameters were determined from 3 technical replicates. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

To investigate the binding activity of RBD-Az before and after conjugation to DNA-VLPs, we conducted flow cytometry experiments with ACE2-expressing HEK293 cells (Figure 2A). Initially, monovalent binding of wild-type RBD and fluorophore-labeled RBD-Cy5, obtained by selectively labeling the azide, was compared (Figure 2B and C). The RBD constructs were incubated at 200 nM with the HEK293 cells and bound antigen was detected using the previously described anti-RBD antibody CR302262. These experiments revealed comparable binding between the two constructs, demonstrating preservation of binding activity of the receptor binding motif (RBM) in RBD and the viability of the reoxidation strategy for selective labeling of the terminal Cys (Figure S2, Note S1).

Figure 2. In vitro activity of RBD-functionalized DNA-VLPs.

(A) An overview of the in vitro activity assays and corresponding DNA-VLPs is shown. (B and C) ACE2-expressing HEK293 cells were incubated with 200 nM RBD. Binding was detected in flow cytometry experiments using PE-labeled CR3022 and a PE-labeled secondary antibody, demonstrating preserved binding activity for chemically modified RBD-Cy5 compared to wild-type RBD. (D and E) Incubation with Cy5-labeled I52-Cy5–30x at 100 nM RBD revealed enhanced binding compared to RBD-Cy5 due to multivalency effects. No unspecific binding for non-functionalized I52-Cy5 was observed. The brightness of Cy5-labeled I52-Cy5–30x (5 Cy5 per 30 RBDs) and RBD-Cy5 (1 Cy5 per 1 RBD) was quantified experimentally (Figure S4) and MFI values were corrected accordingly. (F and G) Ramos B cells expressing the BCRs C3022 and B38 were incubated with α-IgM, wild-type RBD or RBD-functionalized DNA-VLPs at 30 nM RBD. Ca2+ flux in response to RBD incubation was assayed using Fura Red. Representative fluorescence intensity curves are shown (top). Total Ca2+ flux was quantified via the normalized AUC, revealing robust activation of BCR-expressing Ramos B cells by functionalized DNA-VLPs (bottom). No stimulation was observed for wild-type RBD or for non-functionalized I52–0x. Representative histograms are shown for ACE2 binding assays and MFI values were determined from n = 3 biological replicates. Normalized AUC values were determined from n = 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Next, we explored whether multivalent RBD display using DNA-VLPs would result in increased avidity. Two additional fluorophore-labeled DNA-VLPs, I52-Cy5–30x and I52-Cy5, were fabricated to allow for direct detection of binding (Figure 1B and S1). Binding of I52-Cy5–30x was significantly enhanced compared to monomeric RBD-Cy5, while no binding was observed for the I52-Cy5 (Figure 2D and 2E). When correcting for Cy5 brightness per RBD, I52-Cy5–30x displayed approximately one order of magnitude higher median fluorescence intensity compared with monomeric RBD-Cy5, likely due to avidity effects in multivalent DNA-VLP binding to the cognate ACE2 receptor.

We then evaluated the impact of RBD-functionalized DNA-VLPs on BCR signaling using a previously described Ca2+ flux assay (Figure 2A)63. Specifically, Ramos B cell lines expressing the somatic CR3022 or B38 antibodies were established62,66 and BCR signaling was validated by incubation with anti-IgM antibody. At 30 nM antigen concentration, monomeric RBD did not elicit B cell activation in vitro (Figure 2F and 2G). In contrast, incubation of the Ramos B cells with multivalent DNA-VLPs at the same antigen concentration resulted in efficient BCR signaling. We further observed valency-dependent increases in total Ca2+ flux for both cell lines with I52–30x more potent than I52–6x. CR3022 (KD = 0.27 μM, Figure 2F) and B38 (KD = 1.00 μM, Figure 2G) bind distinct RBD epitopes with moderate monovalent affinity as reported for the corresponding Fab fragments67. Despite this four-fold difference in affinity, we observed comparable total BCR signaling relative to the IgM control for all functionalized DNA-VLPs, consistent with previously described avidity effects at the B cell surface68. We thereby concluded that our DNA-VLPs efficiently bound and induced signaling by RBD-specific BCRs in a valency-dependent manner, analogous to previous studies using similar assays to evaluate protein- and DNA-scaffolded multivalent subunit vaccines58,63,64,69–74.

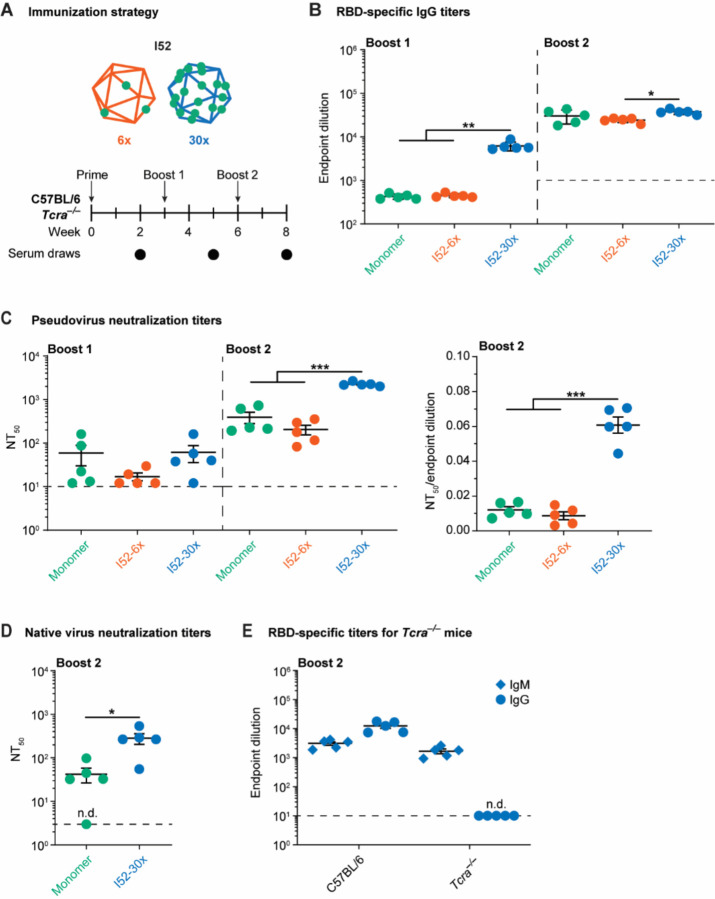

To investigate whether RBD-functionalized DNA-VLPs activated B cells in vivo to induce antibody responses, C57BL/6 mice were sequentially immunized intraperitoneally with monomeric RBD, I52–6x, or I52–30x at doses equivalent to 7.5 μg RBD with Sigma adjuvant (Figure 3A and S3). Serum IgG responses against the RBD were monitored throughout this regimen using ELISA and correlated with in vitro BCR signaling findings (Figure 3B and S5). Following boost 1, we observed an approximately 130-fold increase in endpoint dilutions for I52–30x over monomeric RBD. In contrast, I52–6x elicited comparable antibody responses with respect to monomeric RBD following each boost, suggesting that a higher minimum antigen copy number is needed to enhance B cell responses in vivo compared with in vitro (Figure 2F and 2G), which may be due to differences in trafficking or degradation rates, for example, between I52–6x and I52–30x. Overall, IgG titers increased for monomeric RBD, I52–6x, and I52–30x following boost 2, converging to similar endpoint dilutions. These findings of earlier and stronger boosting of IgG titers and efficient B cell memory recall elicited by the I52–30x are hallmarks of multivalent versus monomeric subunit vaccines23,24, consistent with enhanced IgG titers elicited by P-VLPs of increasing valency8–10.

Figure 3. RBD-specific antibody responses to functionalized DNA-VLPs.

(A) Mice were sequentially immunized with monomeric RBD and RBD-functionalized DNA-VLPs of varying copy number. (B) RBD-specific IgG endpoint dilutions revealed enhanced antibody responses for I52–30x compared to both monomeric RBD and I52–6x. (C) Serum neutralization titers expressed as NT50 values against pseudoviruses modeling the wild-type, Wuhan strain. (D) Neutralization of native Wuhan SARS-CoV-2. (E) IgM and IgG titers of RBD-specific antibodies elicited in Tcra−/− and wild-type mice after sequential immunization with I52–30x. N=5 animals were used in each experimental group. One-way ANOVA was performed followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test at α = 0.05 for (B) and (C). Welch’s t-test was performed at α = 0.05 for (D). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Non-responder mice (denoted as n.d. = not detectable) were not considered for statistical analysis.

To quantify the quality of antibody responses generated by DNA-VLPs, valencydependent enhancement of RBD-specific antibody responses was interrogated using viral neutralization assays (Figure 3C, 3D and S6). In both pseudo- and native virus neutralization assays, efficient neutralization of the wild-type, Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2 resulted from DNA-VLPs. However, across both the pseudo- and native virus assays, I52–30x elicited IgG titers with significantly higher neutralization potency compared with both monomeric RBD and I52–6x, indicating that the higher valency, 30x-RBD DNA-VLP produced significantly superior quality antibodies, which have been correlated with improved patient outcomes75–77.

To confirm that the boosted, RBD-specific IgG titers were achieved via the TD route, we compared the same sequential immunization regime in wild-type C57BL/6 versus Tcra−/− mice that lack functional TCRs78 (Figure 3A). I52–30x elicited robust IgM responses in both genotypes, whereas RBD-specific IgG titers were not boosted in Tcra−/− mice (Figure 3E). Hence, IgG boosting following sequential immunization with DNA-VLPs was due to TD, or T cell dependent, recall of B cell memory.

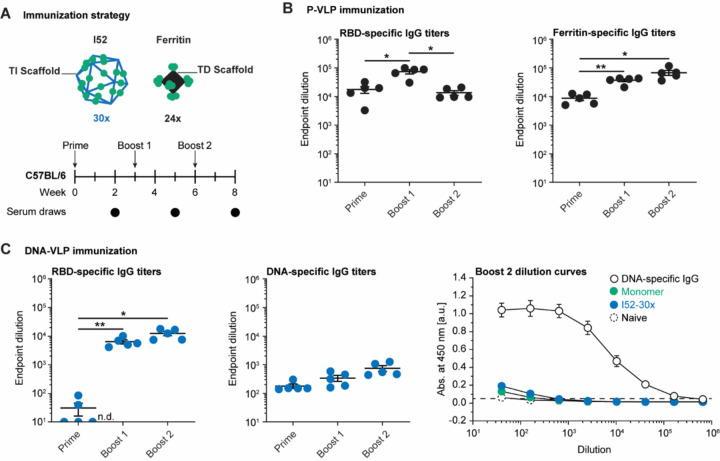

To contrast our findings on DNA-VLPs with protein-based materials, we employed ferritin-based P-VLPs with 24-valent display of RBDs (P-VLP-24x) on a scaffold of approximately 12 nm scaffold diameter (Figure S1)32,39. Following the validation of efficient B cell activation in vitro (Figure S7), C57BL/6 mice were sequentially immunized intraperitoneally with monomeric wild-type RBD, I52–30x, or P-VLP-24x at doses equivalent to 7.5 μg RBD (Figure 4A). While RBD-specific IgG titers were enhanced for both I52–30x and P-VLP-24x (Figure 4B and 4C), P-VLP-24x also exhibited boosted IgG titers against the ferritin protein scaffold itself (Figure 4B). In contrast, we did not observe boosting of DNA-specific IgG titers following immunization with DNA-VLPs, indicating an absence of B cell memory of the DNA-based scaffold (Figure 4C and S8). Importantly, this same behavior was observed when a higher DNA dose was administered (I52–6x) and also when monomeric RBD was administered (Figure S8).

Figure 4. Scaffold-specific antibody responses to functionalized DNA-VLPs and P-VLPs.

(A) Mice were sequentially immunized with monomeric RBD, RBD-functionalized DNA-VLP, or ferritin-based P-VLP. (B) RBD-specific and scaffold-specific IgG endpoint dilutions for the P-VLP immunization. (C) RBD-specific and scaffold-specific IgG endpoint dilutions for the DNA-VLP immunization; dilution curves for Boost 2 of the DNA-specific ELISA. The DNA-specific IgG control was diluted from 10 μg/ml. N=5 animals were used in each experimental group. One-way ANOVA was performed followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test at α = 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Non-responder mice (denoted as n.d. = not detectable) were not considered for statistical analysis.

Conclusions

Rational vaccine design seeks to leverage multivalent antigen display together with epitope-focusing to generate potent, neutralizing antibody responses79. P-VLPs have demonstrated limited control over antigen valency and antigen type8,9,29,38 together with low-cost, scalable production27,30,32,38, but they suffer from the generation of distracting, off-target antibody responses against the protein scaffold material itself39,40,50.

As an alternative VLP scaffold material, here we investigated the multivalent display of the RBD antigen from SARS-CoV-2 using icosahedral DNA origami VLPs. Our results suggest that DNA-VLPs covalently functionalized with 30 copies of the RBD antigen significantly enhance neutralizing antibody responses compared with monomeric RBD antigen alone, consistent with findings for P-VLPs displaying RBD10,30,32,33,38,39, as well as other antigens8,9,23. However, unlike P-VLPs that elicit scaffold-directed humoral immunity within the memory compartment32,33,38,39, compatible with our findings here for a ferritin-based P-VLP, DNA-VLPs did not generate B cell memory to the VLP scaffold material itself. Importantly, this suggests that the distraction of antibody responses away from the target protein antigen of interest in P-VLPs, which may reduce cross-neutralization of variants in the case of SARS-CoV-239 and potentially result in irreversible off-target immune imprinting43,44,45,80, may be avoided by DNA-VLPs. While our finding was expected for TI antigens such as DNA, it is also well established that TD antibody responses can be generated for TI antigens covalently attached to protein scaffolds81,82. Our results, however, indicate that the inverse is not necessarily the default, namely scaffolding TD antigens with TI antigens does not generate boostable B cell memory against the TI scaffold for our vaccine platform. At the same time, we observed robust valency-dependent TD antibody responses to the RBD, akin to virosomal and ISCOM-based vaccine designs in which protein antigens are multivalently displayed by TI antigen-composed matrices83–86.

Because DNA origami uniquely offers simultaneous yet independent control over spatial antigen display, scaffold size, and scaffold geometry, we were able to investigate the impact of antigen valency alone on antibody responses using an optimally sized, geometrically fixed ~35 nm icosahedral VLP scaffold, whereby 30 but not six copies of RBD were found to be sufficient to enhance neutralizing antibody titers compared with monomeric RBD alone. Future work may seek to additionally examine the impact of antigen spacing with fixed valency58, as well as alternative scaffold sizes and geometries, which might ultimately be required to resolve critical thresholds for enhancing antibody responses beyond monomeric antigens, as well as to optimize B cell responses for certain antigens9,29,30. Additional important extensions to our study include examining GC formation in B cell follicles, which is known to be important to generate broadly neutralizing antibodies and long-lived humoral immunity87–89. Toward this end, it will be interesting to investigate to what extent multivalent antigen display by DNA-VLPs is maintained in secondary lymphoid organs, particularly in the presence of endonuclease90,91 and protease89 degradation; what the breadth of neutralizing antibody responses is; and what the longevity of humoral immunity is. To further enhance B cell activation and trafficking to secondary lymphoid organs, DNA-VLP valency may be increased, slow escalating dosing may be used92, and active follicle targeting with carbohydrates may be incorporated5,87. Co-formulation with TLR-based adjuvants may also be used to enhance T cell help, drive GC reactions, and improve humoral immunity93–95. Finally, DNA stabilization strategies91 may be needed to increase the longevity of DNA-VLPs within follicles and GCs in the presence of endonucleases.

Beyond rational vaccine design and promoting antibody focusing, our discovery that DNA scaffolds are not neutralized by DNA-specific antibodies is of significant importance towards enabling redosing in therapeutic nucleic acid delivery by avoiding antibody-dependent clearance46,47, whereby DNA origami may offer an important delivery vector96.

Methods

Methods are described in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

E.-C.W., G.K., and M.B. were supported by NIH R21-EB026008, NSF CCF-1564025, CBET-1729397, and CCF-1956054, ONR N00014-21-1-4013 and N00014-17-1-2609, ARO ISN W911NF-13-D-0001, and Fast Grants Agreement EFF 4/15/20. E.-C. W. was additionally supported by the Feodor Lynen Fellowship of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. B.M.H was supported by NIGMS (T32GM007753) and F30 AI160908. J.F. was supported by NIGMS (T32AI007245). A.G.S. was supported by NIH (R01 AI146779) and a Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogenesis Readiness (MassCPR) grant. D.L was supported by NIH (R01AI124378, R01AI153098, R01AI155447, U19AI057229, P30AI060354). The SARS-CoV-2 virus work was performed at the Ragon Institute’s Biosafety Level 3 facility, which is supported by the NIH-funded Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI060354) and the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness (MassCPR).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has filed a patent (US application number 16/752,394) covering the use of DNA origami as a vaccine platform on behalf of the co-inventors (E.-C. W. and M. B.).

Software and code availability

No previously unreported code or software were used for data collection and analysis.

Data availability

The DNA sequences used to assemble the wireframe DNA origami are included in Tables S1–3. All data files used to generate the figures in this manuscript are available from A. S., D. L. or M. B. upon request.

References

- 1.Singh A. Eliciting B cell immunity against infectious diseases using nanovaccines. Nat Nanotechnol 16, 16–24, doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-00790-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen B. & Tolia N. H. Protein-based antigen presentation platforms for nanoparticle vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 6, 70, doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00330-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irvine D. J. & Read B. J. Shaping humoral immunity to vaccines through antigen-displaying nanoparticles. Curr Opin Immunol 65, 1–6, doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.01.007 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y. N. et al. Nanoparticle Size Influences Antigen Retention and Presentation in Lymph Node Follicles for Humoral Immunity. Nano Lett 19, 7226–7235, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02834 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yousefpour P., Ni K. & Irvine D. J. Targeted modulation of immune cells and tissues using engineered biomaterials. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 1, 107–124, doi: 10.1038/s44222-022-00016-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batista F. D., Iber D. & Neuberger M. S. B cells acquire antigen from target cells after synapse formation. Nature 411, 489–494, doi: 10.1038/35078099 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott R. K. et al. Precursor Frequency and Affinity Determine B Cell Competitive Fitness in Germinal Centers, Tested with Germline-Targeting HIV Vaccine Immunogens. Immunity 48, 133–146 e136, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.023 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcandalli J. et al. Induction of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by a Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Cell 176, 1420–1431 e1417, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.046 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato Y. et al. Multifaceted Effects of Antigen Valency on B Cell Response Composition and Differentiation In Vivo. Immunity 53, 548–563 e548, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.08.001 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He L. et al. Single-component, self-assembling, protein nanoparticles presenting the receptor binding domain and stabilized spike as SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates. Sci Adv 7, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abf1591 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batista F. D. & Harwood N. E. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 9, 15–27, doi: 10.1038/nri2454 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwak K., Akkaya M. & Pierce S. K. B cell signaling in context. Nat Immunol 20, 963–969, doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0427-9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold M. R. & Reth M. G. Antigen Receptor Function in the Context of the Nanoscale Organization of the B Cell Membrane. Annu Rev Immunol 37, 97–123, doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041704 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dintzis H. M., Dintzis R. Z. & Vogelstein B. Molecular determinants of immunogenicity: the immunon model of immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73, 3671–3675, doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3671 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tittle T. V. & Rittenberg M. B. IgG B memory cell subpopulations: differences in susceptibility to stimulation by TI-1 and TI-2 antigens. J Immunol 124, 202–206 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obukhanych T. V. & Nussenzweig M. C. T-independent type II immune responses generate memory B cells. J Exp Med 203, 305–310, doi: 10.1084/jem.20052036 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinuesa C. G. & Chang P. P. Innate B cell helpers reveal novel types of antibody responses. Nat Immunol 14, 119–126, doi: 10.1038/ni.2511 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerutti A., Cols M. & Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 118–132, doi: 10.1038/nri3383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crotty S. T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity 50, 1132–1148, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.04.011 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victora G. D. & Nussenzweig M. C. Germinal Centers. Annu Rev Immunol 40, 413–442, doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-120419-022408 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cyster J. G. & Allen C. D. C. B Cell Responses: Cell Interaction Dynamics and Decisions. Cell 177, 524–540, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.016 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyoglu-Barnum S. et al. Quadrivalent influenza nanoparticle vaccines induce broad protection. Nature 592, 623–628, doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03365-x (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanekiyo M. et al. Self-assembling influenza nanoparticle vaccines elicit broadly neutralizing H1N1 antibodies. Nature 499, 102–106, doi: 10.1038/nature12202 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanekiyo M. et al. Rational Design of an Epstein-Barr Virus Vaccine Targeting the Receptor-Binding Site. Cell 162, 1090–1100, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.043 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanekiyo M. et al. Mosaic nanoparticle display of diverse influenza virus hemagglutinins elicits broad B cell responses. Nat Immunol 20, 362–372, doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0305-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Murillo P. et al. Particulate Array of Well-Ordered HIV Clade C Env Trimers Elicits Neutralizing Antibodies that Display a Unique V2 Cap Approach. Immunity 46, 804–817 e807, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.021 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akahata W. et al. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med 16, 334–338, doi: 10.1038/nm.2105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arunachalam P. S. et al. Adjuvanting a subunit COVID-19 vaccine to induce protective immunity. Nature 594, 253–258, doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03530-2 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen A. A. et al. Mosaic nanoparticles elicit cross-reactive immune responses to zoonotic coronaviruses in mice. Science 371, 735–741, doi: 10.1126/science.abf6840 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen A. A. et al. Mosaic RBD nanoparticles protect against challenge by diverse sarbecoviruses in animal models. Science, eabq0839, doi: 10.1126/science.abq0839 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalvie N. C. et al. Engineered SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain improves manufacturability in yeast and immunogenicity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106845118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King H. A. D. et al. Efficacy and breadth of adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain nanoparticle vaccine in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106433118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joyce M. G. et al. SARS-CoV-2 ferritin nanoparticle vaccines elicit broad SARS coronavirus immunogenicity. Cell Rep 37, 110143, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110143 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yassine H. M. et al. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med 21, 1065–1070, doi: 10.1038/nm.3927 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jardine J. G. et al. Priming a broadly neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1 using a germline-targeting immunogen. Science 349, 156–161, doi: 10.1126/science.aac5894 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peabody D. S. et al. Immunogenic display of diverse peptides on virus-like particles of RNA phage MS2. J Mol Biol 380, 252–263, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.049 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon J. J. et al. Enhancing humoral responses to a malaria antigen with nanoparticle vaccines that expand Tfh cells and promote germinal center induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 1080–1085, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112648109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walls A. C. et al. Elicitation of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 183, 1367–1382 e1317, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauser B. M. et al. Rationally designed immunogens enable immune focusing following SARS-CoV-2 spike imprinting. Cell Rep 38, 110561, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110561 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraft J. C. et al. Antigen- and scaffold-specific antibody responses to protein nanoparticle immunogens. Cell Rep Med 3, 100780, doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100780 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herzenberg L. A., Tokuhisa T. & Herzenberg L. A. Carrier-priming leads to haptenspecific suppression. Nature 285, 664–667, doi: 10.1038/285664a0 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chackerian B., Durfee M. R. & Schiller J. T. Virus-like display of a neo-self antigen reverses B cell anergy in a B cell receptor transgenic mouse model. J Immunol 180, 5816–5825, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5816 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wheatley A. K. et al. Immune imprinting and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine design. Trends Immunol 42, 956–959, doi: 10.1016/j.it.2021.09.001 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Francis T. On the Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin. Proc Am Philos Soc 104, 572–578 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monto A. S., Malosh R. E., Petrie J. G. & Martin E. T. The Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin: Separating Good From Evil. J Infect Dis 215, 1782–1788, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix173 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alonso-Padilla J. et al. Development of Novel Adenoviral Vectors to Overcome Challenges Observed With HAdV-5-based Constructs. Mol Ther 24, 6–16, doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.194 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zak D. E. et al. Merck Ad5/HIV induces broad innate immune activation that predicts CD8(+) T-cell responses but is attenuated by preexisting Ad5 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, E3503–3512, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208972109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucas C. R. et al. DNA Origami Nanostructures Elicit Dose-Dependent Immunogenicity and Are Nontoxic up to High Doses In Vivo. Small 18, e2108063, doi: 10.1002/smll.202108063 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X. et al. A DNA nanostructure platform for directed assembly of synthetic vaccines. Nano Lett 12, 4254–4259, doi: 10.1021/nl301877k (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olshefsky A., Richardson C., Pun S. H. & King N. P. Engineering Self-Assembling Protein Nanoparticles for Therapeutic Delivery. Bioconjug Chem, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00030 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rothemund P. W. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297–302, doi: 10.1038/nature04586 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veneziano R. et al. Designer nanoscale DNA assemblies programmed from the top down. Science 352, 1534, doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4388 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knappe G. A., Wamhoff E. C., Read B. J., Irvine D. J. & Bathe M. In situ covalent functionalization of DNA origami virus-like particles. ACS Nano 15, 14316–14322, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c03158 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jun H. et al. Rapid prototyping of arbitrary 2D and 3D wireframe DNA origami. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 10265–10274, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab762 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wamhoff E. C. et al. Programming structured DNA assemblies to probe biophysical processes. Annu Rev Biophys 48, 395–419, doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-052118115259 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knappe G. A., Wamhoff E. C. & Bathe M. Functionalizing DNA origami to investigate and interact with biological systems. Nat Rev Mater 8, 123–138, doi: 10.1038/s41578-022-00517-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaw A. et al. Binding to nanopatterned antigens is dominated by the spatial tolerance of antibodies. Nat Nanotechnol 14, 184–190, doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0336-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Veneziano R. et al. Role of nanoscale antigen organization on B-cell activation probed using DNA origami. Nat Nanotechnol 15, 716–723, doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0719-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai L. & Gao G. F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 73–82, doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00480-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kleanthous H. et al. Scientific rationale for developing potent RBD-based vaccines targeting COVID-19. NPJ Vaccines 6, 128, doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00393-6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walls A. C. et al. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan M. et al. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science 368, 630–633, doi: 10.1126/science.abb7269 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weaver G. C. et al. In vitro reconstitution of B cell receptor-antigen interactions to evaluate potential vaccine candidates. Nat Protoc 11, 193–213, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.009 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jardine J. et al. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science 340, 711–716, doi: 10.1126/science.1234150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bar-On Y. M., Flamholz A., Phillips R. & Milo R. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers. Elife 9, doi: 10.7554/eLife.57309 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu Y. et al. A noncompeting pair of human neutralizing antibodies block COVID-19 virus binding to its receptor ACE2. Science 368, 1274–1278, doi: 10.1126/science.abc2241 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hauser B. M. et al. Engineered receptor binding domain immunogens elicit pan-sarbecovirus neutralizing antibodies outside the receptor binding motif. bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2020.12.07.415216 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lingwood D. et al. Structural and genetic basis for development of broadly neutralizing influenza antibodies. Nature 489, 566–570, doi: 10.1038/nature11371 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sangesland M. et al. Germline-Encoded Affinity for Cognate Antigen Enables Vaccine Amplification of a Human Broadly Neutralizing Response against Influenza Virus. Immunity 51, 735–749 e738, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saunders K. O. et al. Targeted selection of HIV-specific antibody mutations by engineering B cell maturation. Science 366, doi: 10.1126/science.aay7199 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McGuire A. T. et al. Engineering HIV envelope protein to activate germline B cell receptors of broadly neutralizing anti-CD4 binding site antibodies. J Exp Med 210, 655–663, doi: 10.1084/jem.20122824 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corbett K. S. et al. Design of Nanoparticulate Group 2 Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Stem Antigens That Activate Unmutated Ancestor B Cell Receptors of Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Lineages. mBio 10, doi: 10.1128/mBio.02810-18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ronsard L. et al. Engineering an Antibody V Gene-Selective Vaccine. Front Immunol 12, 730471, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.730471 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voss J. E. et al. Reprogramming the antigen specificity of B cells using genome-editing technologies. Elife 8, doi: 10.7554/eLife.42995 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia-Beltran W. F. et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell 184, 476–488 e411, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.015 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia-Beltran W. F. et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell 184, 2523, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.006 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hauser B. M. et al. Cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 epitope targeted across donors informs immunogen design. Cell Rep Med 3, 100834, doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100834 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mombaerts P. et al. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature 360, 225–231, doi: 10.1038/360225a0 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Correia B. E. et al. Proof of principle for epitope-focused vaccine design. Nature 507, 201–206, doi: 10.1038/nature12966 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schiepers A. et al. Molecular fate-mapping of serum antibody responses to repeat immunization. Nature 615, 482–489, doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05715-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rappuoli R. Glycoconjugate vaccines: principles and mechanisms. Sci Transl Med 10, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4615 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schumann B. et al. A semisynthetic Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 8 glycoconjugate vaccine. Sci Transl Med 9, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5347 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tian J. H. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373 immunogenicity in baboons and protection in mice. Nat Commun 12, 372, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20653-8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heath P. T. et al. Safety and Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 385, 1172–1183, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107659 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huckriede A., Bungener L., Daemen T. & Wilschut J. Influenza virosomes in vaccine development. Methods Enzymol 373, 74–91, doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)73005-5 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morein B., Sundquist B., Hoglund S., Dalsgaard K. & Osterhaus A. Iscom, a novel structure for antigenic presentation of membrane proteins from enveloped viruses. Nature 308, 457–460, doi: 10.1038/308457a0 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tokatlian T. et al. Innate immune recognition of glycans targets HIV nanoparticle immunogens to germinal centers. Science 363, 649–654, doi: 10.1126/science.aat9120 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tam H. H. et al. Sustained antigen availability during germinal center initiation enhances antibody responses to vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E6639–E6648, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606050113 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aung A. et al. Low protease activity in B cell follicles promotes retention of intact antigens after immunization. Science 379, eabn8934, doi: 10.1126/science.abn8934 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wamhoff E. C. et al. Controlling Nuclease Degradation of Wireframe DNA Origami with Minor Groove Binders. ACS Nano, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c11575 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chandrasekaran A. R. Nuclease resistance of DNA nanostructures. Nat Rev Chem 5, 225–239, doi: 10.1038/s41570-021-00251-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee J. H. et al. Long-primed germinal centres with enduring affinity maturation and clonal migration (vol 609, pg 998, 2022). Nature, doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05741-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu S. et al. A DNA nanodevice-based vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Mater 20, 421–430, doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0793-6 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Du R. R. et al. Innate Immune Stimulation Using 3D Wireframe DNA Origami. ACS Nano 16, 20340–20352, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c06275 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Comberlato A., Koga M. M., Nussing S., Parish I. A. & Bastings M. M. C. Spatially Controlled Activation of Toll-like Receptor 9 with DNA-Based Nanomaterials. Nano Lett 22, 2506–2513, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c00275 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dobrovolskaia M. A. & Bathe M. Opportunities and challenges for the clinical translation of structured DNA assemblies as gene therapeutic delivery and vaccine vectors. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 13, e1657, doi: 10.1002/wnan.1657 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The DNA sequences used to assemble the wireframe DNA origami are included in Tables S1–3. All data files used to generate the figures in this manuscript are available from A. S., D. L. or M. B. upon request.