Abstract

Treatment resistance and drug-induced refractory malignancies pose significant challenges for current chemotherapy drugs. There have been increasing research efforts aimed at developing novel chemotherapeutics, especially from natural products and related derivatives. Natural cytotoxic peptides, an emerging source of chemotherapeutics, have exhibited the advantage of overcoming drug resistance and displayed broad-spectrum antitumor activities in the clinic. This Highlight examines the increasingly popular cytotoxic peptides from isolated natural products. In-depth review of several peptides provides examples for how this novel strategy can lead to the improved anti-tumor effects. The mechanisms and current application of representative natural cytotoxic peptides (NCPs) have also been discussed, with a particular focus on future directions for interdisciplinary research.

Graphical Abstract

This highlight reviews the chemical and mechanistic basis of diverse natural cytotoxic peptides, emphasizing the importance of natural peptides as promising novel chemotherapeutic drugs.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem and has become the second leading cause of death worldwide, after cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Despite considerable progress in the treatment of various forms of cancer, each of the current therapies still has its own limitation(s). For early stage cancer, surgery and radiation are effective approaches to remove primary tumors. However, local treatments cannot prevent tumor invasion/metastasis, and the metastatic spread of tumor cells is the primary cause of cancer-related mortality.1 Immunotherapy is revolutionizing the treatment of cancer by checkpoint blockade of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) pathway. However, only a relatively small group of patients responds to immune-checkpoint blockade therapy and considerable uncertainty remains in the application of cancer immunotherapy. In contrast, chemotherapeutics, including anthracyclines and taxanes, are still listed as first-line drugs for the systemic treatment of advanced and metastatic cancers, despite the acute nonspecific cytotoxicity against normal tissues and the risk of developing multi-drug resistance,.2 Over the last two decades, cytotoxic peptides have emerged as promising chemotherapeutics to combat cancer and multidrug resistant infections.

As natural defences, peptide-based toxins and skin secretions from animals have been used to cope with external threats (e.g., predators). At the same time, peptidyl components from endogenic immune/defence systems have also shown potential anti-bacteria and antitumor effects. Because of their unique structural and mechanistic diversity, these natural cytotoxic peptides (NCPs) provide an unparalleled source of lead compounds for chemotherapeutic development, and continue to play an important role in antitumor drug discovery and development.

In comparison to ‘traditional’ small-molecule chemotherapeutics that often non-selectively inhibit cellular growth in both normal and neoplastic tissues,3 NCPs have exhibited several highly appealing properties: 1) they typically range from 5 to 50 amino acid residues in length, making it easy for chemical synthesis and modification; 2) some relatively selective NCPs exhibit minimal off-target effects; 3) the most common multiple-targeted mechanisms of cytotoxic peptides, especially those selective for tumor-specific cell membrane lysis, are believed to overcome certain forms of drug resistance; and 4) their molecular scaffolds are suitable to modulate relatively undruggable targets and/or protein-protein interactions.4 After comprehensively considering the species source (animal, plant and microorganism), structural diversity (α-helix, β-sheets, loop alone or in combination) and significance of NCPs, we chose a series of representative NCPs to highlight their well-studied therapeutic targets and latest applications.

However, it is worth noting that the successful translation of NCPs still has some challenges, including suboptimal therapeutic activity, structural instability, potential off-target effects, and restricted membrane-permeability. To address those shortcomings, we also proposed the potential solutions and future directions to advance NCPs-based chemotherapeutic drug discovery.

2. Antitumor targets of NCPs

2.1. Cell membrane

There are two types of mechanisms involved in the membrane disruption/permeation effects of NCPs: “carpet-like” and “toroidal pore” models. In the “carpet-like” model, the NCPs are placed in parallel to the cell membrane, like a carpet within a structure.5 Aurein 1.2 and citropin 1.1 (Fig. 1, Table 1) are a family of peptides (13–25 residues) that were originally isolated from the defensive skin secretions of the closely related Australian tree frogs Litoria aurea and Litoria citrpoa, respectively.6–7 As surface-acting membrane disrupting peptides, they both display a broad-spectrum inhibitory effects on over 90% of the tumor cell lines from the US National Cancer Institute’s 60-cell line panel via the “carpet-like” mechanism [Fig. 2(1)].8 The C-terminal amide group has been shown to be critical for structural stabilization, charge, and bioactivity.8 In the “toroidal model”, the NCPs with lipid headgroups are vertically embedded in the plasma membrane bilayer. For example, magainin 2 (Fig. 1, Table 1), a class of α-helical antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from the skin of the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, can irreversibly lyse tumor cells by inducing transmembrane pores like a typical “toroidal model” agent [Fig. 2(1)], and have a relatively low toxicity towards normal cells.9–10

Fig. 1.

Structural diagram of representative NCPs generated using PyMOL. Aurein 1.2 (Protein Data Bank ID: 1VM5), Magainin 2 (Protein Data Bank ID:2MAG), Crotamine (Protein Data Bank ID: 1Z99), TxID (Protein Data Bank ID: 2M3I), Tv1 (Protein Data Bank ID: 2MIX), κ-PVIIA (Protein Data Bank ID: 2N8E), human neutrophil peptide-1 (Protein Data Bank ID: 3GNY), Melittin (Protein Data Bank ID: 2MLT), Tachyplesin Ⅰ (Protein Data Bank ID: 1WO1), Lactoferricin B (Protein Data Bank ID: 1LFC).

Table 1.

The target(s), species, name, and sequence of representative NCPs. (Two cysteines with the same number form corresponding disulfide bond)

| Target(s) | Species | Name | Sequence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell membrane | Litoria aurea | Aurein 1.2 | GLFDIIKKIAESF-NH2 | 6 |

| Litoria citropa | Citropin 1.1 | GLFDVIKKVASVIGGL-NH2 | 7 | |

| Xenopus laevis | Magainin 2 | GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS | 36 | |

| Anoplius samariensis | Anoplin | GLLKRIKTLL-NH2 | 15 | |

| Ion channel | Conus textile | TxID | GC1C2SHPVC1SAMSPIC2-NH2 | 19 |

| Terebra variegata | Tv1 | TRIC1C2GC3YWNGSKDVC3SQSC1C2 | 23 | |

| Conus purpurascens | κ-PVIIA | C1RIPNQKC2FQHLDDC3C2SRKC1NRFNKC3V | 25 | |

| Cytoskeleton | Symploca sp. VP642 | Dolastatin 10 | Refer to Fig. 3 | 29 |

| Organelles | Crotalus durissus terrifcus | Crotamine | YKQC1HKKGGHC2FPKEKIC3LPPSSDFGKMDC2RWRWKC1C3KKGSG | 37 |

| Cell cycle and apoptosis | Trididemnum solidum | Didemnin B | Refer to Fig. 3 | 38 |

| Aplidium albicans | Plitidepsin | Refer to Fig. 3 | 39 | |

| Tumor angiogenesis | Homo sapiens | Human neutrophil peptide-1 | AC1YC2RIPAC3IAGERRYGTC2IYQGRLWAFC3C1 | 40 |

| Multi-target synergistic effect targets | Apis mellifera | Melittin | GIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQ-NH2 | 41 |

| Tachypleus tridentatus | Tachyplesin Ⅰ | KWC1FRVC2YRGIC2YRRC1R-NH2 | 42 | |

| Bos taurus | Lactoferricin B | FKCRRWQWRMKKLGAPSITCVRRAF | 43 | |

| Glycine max | Lunasin | SKWQHQQDSCRKQLQGVNLTPCEKHIMEKIQGRGDDDDDDDDDN | 44 | |

| Homo sapiens | LL-37 | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES | 45 |

Fig. 2.

Antitumor targets of NCPs. 1) NCPs lyse cell membrane by the “carpet-like” and “toroidal pore” models; 2) NCPs block various ion channels that are overexpressed on cell membrane; 3) Microtubules are inhibited by dolastatin 10; 4) Crotamine causes depolarization of mitochondrial membrane and induces tumour cell death; 5) Didemnin B displays antitumor activity through the inhibition of cell cycle; 6) Plitidepsin interacts with eEF1A2 which involved in the oxidative stress/p38-MAPK pathway and FAS/CD95 pathway, and subsequent apoptotic program; 7) Human neutrophil peptide-1 specifically binds to integrin and suppresses angiogenesis; 8) Lunasin inhibits acetylation of core histones H3 and H4; 9) Tumor-associated antigens induced by Lactoferricin B treatment are released into the tumor microenvironment (TME), and cause systemic immune response. NCPs are shown as green ribbon or stick and ball models.

The tumor cell selectivity of NCPs may result from the physiological and biochemical differences between tumor and normal cells. For example, the abundance of anionic substances (i.e., phosphatidylserine and heparan sulfate) in tumor cells increase the negative charge on cell membrane.11 The surface of normal cell membrane is mainly composed of neutral phospholipids and sterols, and the relatively abundant membrane-bound cholesterol can also protect normal cells from NCPs by altering membrane fluidity.12 Cationic NCPs possess the ability to form membrane potential-mediated electrostatic interactions, thereby displaying a selectivity not achievable with ‘traditional’ chemotherapeutic drugs.13 Tumor cells distinctly have more microvilli than normal cells, and these microvilli can increase the surface area for increased NCP binding.14 These factors are all significant contributors to the tumor cell selectivity of NCPs. Anoplin (Table 1), the shortest peptide from wasp venom, is one of the representative NCPs with high selectivity towards tumor cells. It exerts lytic activity on tumor cells without detectable haemolytic activity in red blood cells.15

The membrane-lytic mechanism of NCPs offers an attractive solution for cancer related multidrug-resistance (MDR). In general, the response of cancer cells to chemotherapy correlates with the intracellular concentration of chemotherapeutic agents, that is determined by the balance between drug influx and efflux.16 Drug efflux pumps (e.g. P-glycoprotein and multidrug-resistance protein-mediated) function as vital MDR factors that contribute to the accelerated efflux of chemotherapeutics, and eventually lead to the reduced sensitivity to chemotherapy.17 In this context, cell membrane lysis by NCPs has a much lower tendency to induce MDR when compared with conventional chemotherapeutic agent.

2.2. Ion channel

Ion channels are a class of membrane proteins that are often overexpressed in many forms of cancer, and the selective blockade of ion channels is envisioned to have potential therapeutic effects on cancer.18 Among these ion channels, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) play a pivotal role in cancer development. Members of a ligand-gated ion channel family, nAChRs are composed of five distinct subunits (i.e., α, β, γ, δ and ε) that are further divided into different subtypes. The Conus textile α‑conotoxin TxID (Fig. 1, Table 1) is an α3β4 nAChR selective antagonist with the potential for development as a novel anticancer drug.19 The synthetic TxID has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of cervical20 and lung cancer cells,21 mediated through the α3β4 nAChRs which provide a potentially novel basis for chemotherapeutic intervention [Fig. 2(2)].

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, members of the Ca2+ channel family, are intimately associated with cancer initiation and metastasis by modulating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.22 Toxin Tv1 (Fig. 1, Table 1), a bioactive disulfide-rich peptide isolated from predatory marine snail Terebra variegate, has a unique structural scaffold in comparison to other snail venom peptides.23 Results from in vitro and in vivo studies on chemically synthesized Tv1 revealed that Tv1 selectively inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells and significantly reduced tumor size in a syngeneic mouse model, through the modification of TRPC6 and/or TRPV6 channels [Fig. 2(2)] that are overexpressed in the HCC models.24 Similarly, κ-conotoxins-PVIIA (κ-PVIIA) (Fig. 1, Table 1), a 27 amino acid peptide from Conus purpurascens venom,25 binds to the potassium channel protein HERG, which is overexpressed on the plasma membrane of many tumor cells [Fig. 2(2)].26

2.3. Cytoskeleton

Microtubules [Fig. 2(3)] are a critical component of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, which not only maintains cell morphology and intra2cellular structures, but also protects the integrity of cell division, genome replication, and other vital functions.27 Compared with normal cells, tumor cells have underdeveloped cytoskeletons with slower and less effective self-repair due to insufficient microfilament content, resulting in tumor cell death following exposure to NCPs.28 Dolastatin 10 (Fig. 3, Table 1) is an anti-microtubule pentapeptide originally isolated from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia, and subsequently found to be produced by the marine cyanobacterium Symploca sp.29 Dolastatin 10 and analogues (i.e., dolastatin 15 and symplostatin 1) demonstrated subnanomolar anti-proliferative activity in vitro towards various cancer cell lines, but their unfavourable pharmacokinetic profiles limited their further clinical development.30

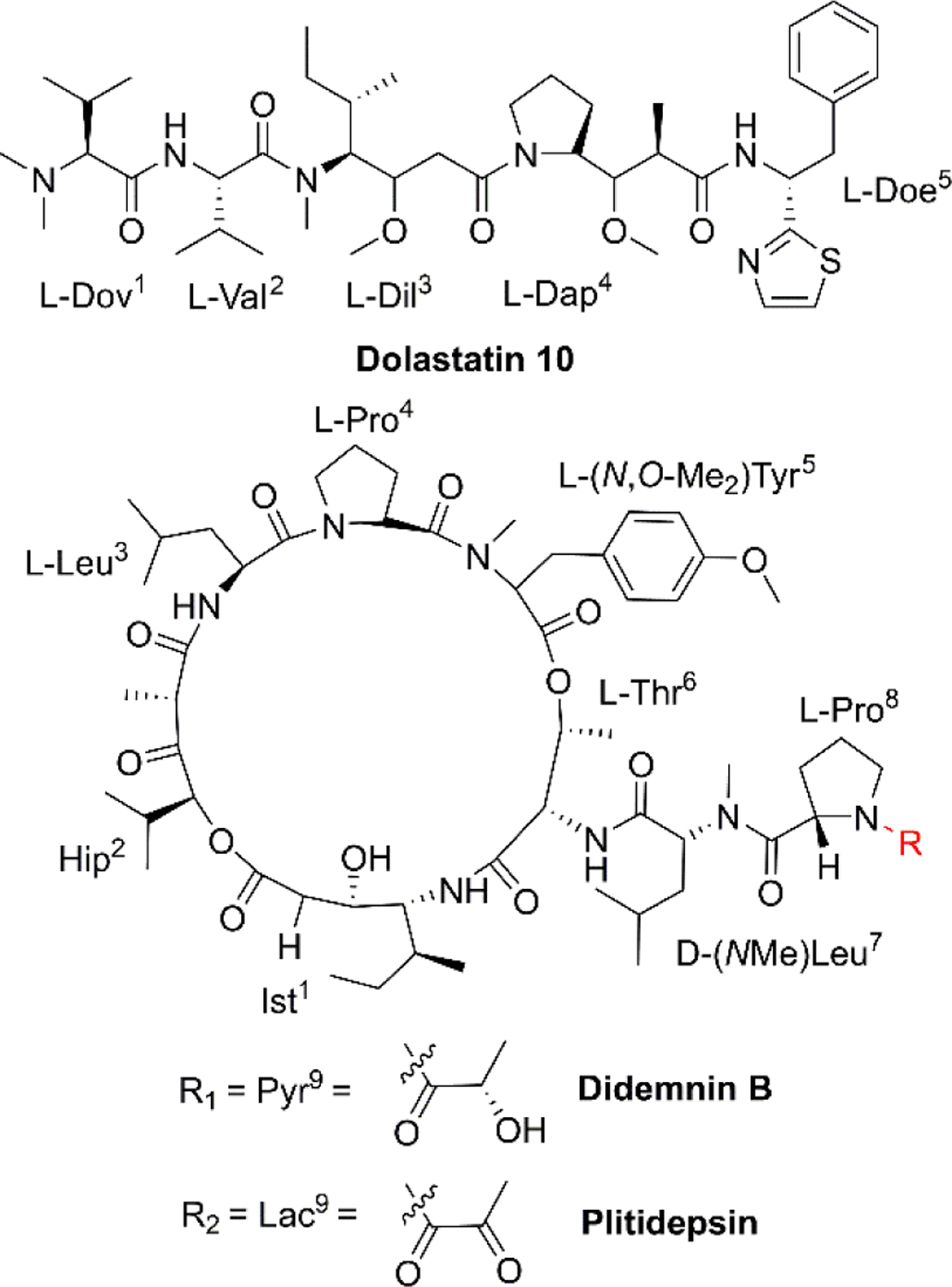

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of dolastatin 10, didemnin B and plitidepsin.

2.4. Organelles

In addition to the well-recognized role as the primary cellular energy powerhouse, mitochondria are also the central regulators of cell death pathways.31 Crotamine (Fig. 1, Table 1), the major component of venom from the South American rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrifcus, is the first venom peptide classified as natural cell penetrating and antimicrobial defensin-like peptide with enhanced antiproliferative activity.32 Its structure encompasses a short N-terminal α-helix and anti-parallel triple-stranded β-sheets arranged in an αβ1β2β3 topology, stabilized by three disulfide bridges.33 Electrostatic interactions are induced between crotamine and the negatively charged cardiolipins within mitochondrial membranes. While inducing a rapid intracellular Ca2+ overload, crotamine can cause depolarization of the inner mitochondrial membrane in B16F10 cells and selectively induce tumor cell death [Fig. 2(4)].34 Notably, the fluorescent derivative of crotamine is also a potent theranostic tool for targeted delivery.35

2.5. Cell cycle and apoptosis

The cell cycle is mainly regulated by various cyclins and cyclin-dependent protein kinases (CDKs). Drugs that inhibit the activity of these enzymes and/or their gene expression can block the progression of the cell cycle and exert favourable antitumor effects.46 The non-ribosomal peptide didemnin B (Fig. 3, Table 1), a marine tunicate (ascidian or sea-squirt)-derived cyclic depsipeptide isolated from Trididemnum solidum, has displayed promising antitumor effects through the inhibition of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis, initiation of apoptosis and G1 to S phase blockade [Fig. 2(5)].38 The unique structural features of didemnin B are the D-configuration of its N-methyl Leu, two specific chemical units (isostatine (Ist) and α-(α-hydroxyisovaleryl) propionyl (HIP)), and two nonproteinogenic L-amino acids (N, O-dimethyl Tyr and pyruvyl Pro).47 As the first marine-derived peptide in clinical trial, the continuous clinical development of didemnin B was hindered by the unsatisfactory response and significant toxicity risk, which could be potentially solved by the development of derivatives.48

Plitidepsin (Fig. 3, Table 1, Table 2,), originally isolated from the Mediterranean tunicate Aplidium albicans in 1990, has been manufactured through total synthesis and commercialized as Aplidin®.39 The first-in-class peptide drug approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), leukemia, and lymphoma,49 plitidepsin is only slightly different from the previously mentioned didemnin B, where a pyruvoyl-proline residue is replaced by a lactyl-proline residue. This minor structural modification causes a striking disparity in the anticancer mechanisms. Plitidepsin can interact with the overexpressed eukaryotic elongation factor 1A2 (eEF1A2) which is involved in the oxidative stress/p38-MAPK pathway, FAS/CD95 pathway, and subsequently induces a rapid apoptotic response [Fig. 2(6)].50

Table 2.

Selected FDA-approved drugs and clinical-stage drug candidates based on NCPs.

| Name | Source | Developer | Clinical Stage | Disease Area | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plitidepsin (Aplidin®) | Plitidepsin | PharmaMar | Approved | Multiple myeloma, leukemia, lymphoma | 40 |

| Enfortumab Vedotinejfv (PADCEV™) | Dolastatin 10 | Astellas Pharma & Seattle Genetics | Approved | Metastatic urothelial cancer | 64 |

| Polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy™) | Dolastatin 10 | Roche/Genetech | Approved | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma, B-Cell and follicular lymphoma | 65 |

| Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) | Dolastatin 10 | Seattle Genetics | Approved | Anaplastic large T-cell systemic malignant lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease | 66 |

| Balixafortide | Polyphemusin | Polyphor | Phase III | Metastatic breast cancer, Locally recurrent breast cancer | 67 |

| LTX-315 | Lactoferricin B | Lytix Biopharma AS | Phase II | Soft tissue sarcoma | 68 |

2.6. Tumor angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from existing vasculature, is required for tumor growth and metastasis.51 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors play an important role in the regulation of the angiogenesis process.52 Chavakis and co-workers found that human neutrophil peptide-1 (HNP-1) (Fig. 1, Table 1), that belongs to a peptide series known as α-defensins, specifically inhibited VEGF-dependent endothelial cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation by forming a ternary complex with fibronectin and α5β1 integrin, and thus suppressed VEGF-induced angiogenesis in vivo [Fig. 2(7)].40 These findings provide new insights into the potential of HNPs as angiogenesis inhibitor. However, the structural complexity of HNP-1, especially the three intramolecular disulfide bridges, increases its synthetic complexity.53

2.7. Multi-target synergistic effect

Melittin (Fig. 1, Table 1), the predominant pharmacologically active component of honeybee venom, is a 26-amino acid, amphipathic, cell-penetrating, α-helical peptide. The helix-interrupting Pro14 (along with Gly12) facilitates the formation of a kinked bend in its structure which could create a donut-shaped toroidal pore within the cell membrane.54 Melittin produces a multi-targeted antitumor effect, that consists of cytolytic activity, antiproliferative, anti-invasion and anti-metastatic effects in vivo.41 However, its relatively low selectivity and hemolytic activity need to be addressed before melittin can be brought into the clinic.55

Tachyplesin I (Fig. 1, Table 1) was extracted from the blood lymphatic granulosa cells of the limulus horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus. This peptide is stabilized by two disulfide bonds (Cys3-Cys16, Cys7-Cys12) that form a uniquely rigid and stable β-hairpin with three tandem tetrapeptide repeats.42 In human gastric adenocarcinoma BGC-823 cells, tachyplesin Ⅰ promoted cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase while decreasing the percentage of cells at S phase, and changed the expression of correlative oncogene and tumor suppressor gene.56 In addition, the activation of C4b and C3b subcomponents of complement was observed in TSU human bladder cancer cells treated with tachyplesin I, suggesting the activation of classic complement cascade.57

Lactoferricin B (LfcinB) (Fig. 1, Table 1) is composed of an 18 amino acid loop formed through disulfide bonding from the bactericidal domain of bovine lactoferrin. It exhibits an α-helical structure in lactoferrin, and becomes an amphipathic structure dominated by β-sheets upon dissociation.43 Both LfcinB and its synthetic analogues have exhibited cytotoxicity against numerous cancer cells at low concentrations with minimal toxicity to normal cells.58–59 Mechanisms responsible for this tumor cell-selective cytotoxicity are multi-faceted, including cell cycle arrest, initiation of apoptosis, induction of tumor necrosis, anti-angiogenesis, inhibition of metastasis, and immune modulation [Fig. 2(9)].60

The soybean metabolite lunasin (Table 1) is a 44 amino acid peptide component of the 2S albumin seed protein with three proposed functional domains that include an aspartic acid tail, an RGD domain, and a chromatin-binding helical domain.44 Its RGD domain is critical for cellular internalization and activity against cancer-stem cells through interaction with the αvβ3 integrin via the FAK/ERK/NF-κB signalling pathway.61 The aspartic acid tail inhibited the acetylation of core histones H3 and H4 and the phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2).62

The peptide LL-37 (Table 1) is the only member of the cathelicidin family isolated from the innate human immune system, and is produced through the selective cleavage of its precursor hCAP-18 by serine protease 3.45 Studies have demonstrated that LL-37 can effectively inhibit tumorigenesis through multiple regulatory effects on tumor cell apoptosis, the cell cycle, immunocyte activation, and autophagy.63

3. Currently approved anticancer applications

3.1. Antibody drug conjugates

Although the application of dolastatin 10 as a single agent requires further investigation, dolastatin 10 and its derivatives monomethyl auristatin E and F (Fig. 4, Table 2), have been chemically connected with monoclonal antibodies via environmental responsive linker forming antibody drug conjugates (ADCs).69 These dolastatin 10 ADCs and other derivatives have been approved by the FDA or are in phase I to III clinical trials. Dolastatin 10-derived ADCs have become an important part of the marine-derived cancer chemotherapeutic pipeline.70 This successful targeted strategy offers innovative anticancer agents for treating otherwise intractable cancers.

Fig. 4.

Chemical structures of antibody drug conjugates based on dolastatin 10, balixafortide and LTX-315.

3.2. Chemical structural modification

Extensive structure-activity relationship research indicates that modification, addition, and elimination of structural components of NCPs can effectively enhance their antitumor activity and stability while reducing toxicity. The best example is balixafortide (POL6326) (Fig. 4, Table 2), a potent, selective antagonist of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) which is primarily expressed by hematopoietic stem cells and leukocytes and overexpressed in numerous human tumor cell lines. Through the binding with its ligand, stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1), CXCR4 can promote tumor immune escape and create a favourable niche for tumor growth and metastasis.71 The design of balixafortide is based on polyphemusin, a natural peptide from the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. Blockade of the CXCR4 pathway by balixafortide plays a key role in the suppression of metastatic spread, sensitization of tumor cells to chemotherapy, and activation of the immune system in the tumor microenvironment (TME).72 The completed results of phase I and Ⅱ trials revealed that balixafortide plus eribulin enhanced antitumor effects in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and improved tolerance relative to eribulin alone, while producing no dose-limiting toxicities.67 Therefore, balixafortide shows great promise for its forthcoming phase III trial (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT03786094).

3.3. Oncolytic immunotherapies

As the first-in-class oncolytic peptide, LTX-315 (Fig. 4, Table 2), a derivative of lactoferricin, can effectively lyse cancer cell membranes while reprograming the TME. Intratumoral treatment with LTX-315 result in rapid cell lysis (necrosis) through membrane destabilization followed by the subsequent release of Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) (such as calreticulin, ATP and high mobility group box protein 1) and tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) into the TME.68 Those intracellular content will initiate the recruitment and maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) into the TME. Mature DCs are then primed for engulfment of whole-cell tumor antigens and subsequent presentation to T cells, creating tumor-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes that are capable of eradicating residual cancer cells.68 The LTX-315 peptide produced a complete tumor regression and systemic immune response in a rat fibrosarcoma model, and overcame the resistance to immunotherapy when combined with CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade therapy.73 These findings suggest its potential as a novel cancer immunotherapeutic agent and an ideal combination choice for other immunotherapies.74 Currently, an Open Label Phase II Single Centre Study is recruiting subjects to determine the safety and effectiveness of LTX-315 to induce T-cell infiltration prior to tumor infiltrating lymphocyte expansion in patients with soft tissue sarcoma (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT03725605).

3.4. Targeted co-delivery systems

For some NCPs, such as melittin, clinical application is limited by nonspecific cytotoxicity, hemolytic effect, or rapid degradation. Recent research efforts in the field of nanotechnology hold promise in overcoming these bottlenecks that hinder the clinical development of certain NCPs. Aronson et al75 successfully integrated such a cytolytic NCP payload into the lipid nanoparticles, and this strategy facilitated the selective destruction of cancer cells while circumventing off-target toxicity towards healthy tissues. Another self-assembling lipid nanoparticle (α-melittin-NP) can also shield cytotoxicity of melittin to antigen presenting cells (APCs), but maintain the its ability to promote whole tumor antigen release in situ and result in the activation of APCs in lymph nodes (LNs). This nanoparticle makes melittin an ideal LN-targeted whole-cell nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy in a synergistic manner.76 Use of the chemotherapeutic agent, doxorubicin (DOX), is associated with a number of serious side effects, including dose-dependent cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal toxicity, bone marrow suppression and potential drug resistance.77 The combination of NCPs and DOX via biocompatible nanomaterials may provide an attractive strategy to overcome the potential toxicities of both agents, while reducing DOX-associated drug resistance. For example, a melittin-RADA32 hybrid peptide hydrogel that was loaded with DOX has been developed. It also regulates the TME for melanoma chemoimmunotherapy. This peptide hydrogel dramatically reduced the side effects of melittin and DOX, while significantly enhanced antitumor efficacy and innate immune response.78 These co-delivery systems have demonstrated the synergistic potential of NCPs and conventional chemotherapeutic drugs to elicit sustained antitumor effects and, thus, provide novel drug discovery paradigms.

4. The potential development of NCPs

Although the translation of NCPs into the clinic has made considerable progress, obstacles still remain in many aspects of drug discovery from NCP candidates. For example, the high proteolytic susceptibility of natural peptides leads to their short half-life and low bioavailability in vivo. The inherent conformational flexibility of NCPs impedes the efficacy in complex physiological environments, and the low membrane permeability limits the interaction with intracellular targets for some NCPs.

4.1. Conformational constraints

To increase stability and improve physicochemical properties of peptides, structurally constrained peptide technologies have been widely adopted in both basic research and industrial production. The constrained/stapled peptide technologies were firstly developed to mimic key binding epitopes of proteins, including α-helix and β-hairpin motifs, for the regulation of intracellular protein-protein interactions. Studies have demonstrated that these constrained peptides possess increased cell permeability and improved stability, exhibit increased binding affinity and target protein specificity. In general, conformational helix constraint is fulfilled by linking one of the termini to a side-chain crosslink, or cross-linking two side-chain residues through structurally diverse chemical bonds.79 Among these, the all-hydrocarbon stapled peptide technology is considered as one of the most successful and promising stapling strategies.80 The peptide, ALRN-6924 (Fig. 5), is an optimized ATSP-7041 derivative that was the first example of an all-hydrocarbon stapled-peptide drug to be evaluated in ongoing clinical trials for advanced solid tumors and lymphomas (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02264613).81 We have applied this stapling strategy to design and synthesize a series of novel hydrocarbon-stapled melittin analogues, and these staple-modified melittin peptides exhibited enhanced anti-hepatoma activity and improved protease resistance relative to native melittin peptides.55 Further, these stapled peptides retained their important peripheral residues that enhance both bioactivity and membrane permeability.82 With the success of these stapling strategies, we anticipate that such stapled peptide technologies will be widely applied in structural modification of other α-helical NCPs and their derivatives.

Fig. 5.

Chemical structures of ATSP-7041 and disulfide bond mimetic of tachyplesin I.

Disulfide-rich scaffolds confer peptides with increased stability and rigidity. However, disulfide isomerases, as well as reductive glutathione in vivo, can affect or dissociate the disulfide bonds, and lead to structural rearrangement with potential loss of activity.83 Hence, the strategy of developing disulfide surrogates is to enhance redox stability and conformation rigidity of NCP analogues. The Brust group84 and Meldal et al.85 used triazole as a disulfide bond mimetic to lock the conformational structure of conotoxin MrIA and tachyplesin I (Fig. 5) without losing biological activities, respectively. Liu et al.83 also developed diaminodiacid-strategy, using C-C and S-C bonds to maintain the β-hairpin ribbon structure of tachyplesin I. It is anticipated that these methods will provide a highly efficient and practically useful strategy to constrain analogues of disulfide bond-containing NCPs for their translational therapeutic development.

4.2. Peptide-drug conjugates

Like most small-molecule drugs, some NCPs are not sufficiently selective for tumor cells over normal cells, resulting in significant clinical toxicity and limited therapeutic index.75 To minimize off-target effects and generalized toxicities, peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) have been developed. The two component conjugates typically contain a peptide and a specific high affinity molecule which is designed to bind to specific binding sites on tumor cells.86 The difunctional PDC, BT1718, is composed of a constrained bicyclic peptide derived from membrane type 1-matrix metalloprotease (MT1-MMP) using a proprietary phage display peptide technology, coupled to mertansine (a thiol-containing maytansinoid-based small molecule toxin). Pre-clinical evaluations have demonstrated that BT1718 can target MT1-MMP which is expressed in a variety of advanced solid tumors, including triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), non-small cell lung cancer, and various sarcomas. Phase Ⅰ trials with BT1718 are underway (Clinical Trials. gov Identifier: NCT03486730). Inspired by BT1718, we hypothesize a possible way to add a transmembrane molecule or functional molecule onto NCPs by using an elaborate linker. For example, cell penetrating peptides (CPPs), such as TAT and poly-Arg or poly-Lys, have been broadly used.87 These CPPs may increase the cell membrane permeability when linked to NCPs, achieving a reasonable level of intracellular target engagement for antitumor activity. Another ingenious design is covering up the cationic charge of NCPs by an anionic sequence via a cleavable linker that is sensitive to the TME. Li and co-workers developed activatable cell lytic peptides targeting TNBC, and these TME -responsive NCPs showed specific targeting in vivo upon systematic administration and displayed no nonspecific toxicity.88 Alternatively, cell targeting peptides, such as RGD211 and NGR212, provide the shortest specific sequences with high affinity to their targets. For example, synthetic RGD-tachyplesin exhibited a doubly targeted inhibitory effect on proliferating endothelial cells and B16 melanoma cells, both in vitro and in vivo.89 Such difunctional or multifunctional conjugates may show promise to greatly accelerate the discovery, optimization, and preclinical evaluation of NCPs and ultimately facilitate the clinical translation of NCPs.

5. Concluding remarks

Solid tumor-forming cancers continue to pose a severe threat to human health worldwide through their uncontrolled growth and ability to form distant metastases. Further, cancer patients are especially susceptible to opportunistic microbial infections due to their weakened immune systems which caused by conventional chemotherapies.90 Compared with traditional chemotherapeutics, NCPs derived from innate immune systems also play a pivotal role in preventing pathogens through their antimicrobial activity.91 Evidence suggests that bacteria exist in symbiotic relationships with certain tumors.92 In such cases, NCPs with both antimicrobial and anticancer activity may have a distinct advantage. Multi-mechanism NCPs can potentially act in a synergistic manner to increase the antitumor efficacy of conventional single-target chemotherapeutics. Multi-drug resistance (MDR) efflux has become a nearly insurmountable bottleneck for the use of certain small-molecule chemotherapeutic agents93 and NCPs offer the potential as new classes of drug candidates with enormous promise to meet the increasing therapeutic needs. The development of NCP-based chemotherapeutics is still in its infancy, and just as with traditional small-molecule based drugs, numerous challenges exist that can hinder their translation into the clinic (e.g., suboptimal therapeutic activity, potential side effects, low stability, and poor membrane-permeability). Recently developed technical innovations and novel strategies in peptide chemistry show potential to address these shortcomings, and improve the pharmacokinetic properties of peptides while reducing associated undesired effects. Taken together, NCP-derived agents and their synthetic analogues hold great promise for the future of novel chemotherapeutic drug discovery.

7. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81903654), Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Young Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning (QD2018035), Shanghai “Chenguang Program” of Education Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No.18CG46), Shanghai Sailing Program (No.19YF1449400), Shanghai Engineering Research Centre for the Preparation of Bioactive Natural Products (16DZ2280200), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC1700200), Graduate Innovation Training research project of the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (NO. Y2019064), and the U.S. NIH grant CA199016.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

8. References

- 1.Mohme M, Riethdorf S and Pantel K, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol, 2017, 14, 155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL and Siegel RL, CA Cancer J. Clin, 2019, 69, 363–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lengauer C, Diaz LJ and Saha S, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov, 2005, 4, 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naylor MR, Bockus AT, Blanco MJ and Lokey RS, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2017, 38, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennison SR, Whittaker M, Harris F and Phoenix DA, Curr. Protein Pept. Sci, 2006, 7, 487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozek T, Bowie JH, Wallace JC and Tyler MJ, Rapid. Commun. Mass Spectrom, 2000, 14, 2002–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle J, Brinkworth CS, Wegener KL, Carver JA, Llewellyn LE, Olver IN, Bowie JH, Wabnitz PA and Tyler MJ, Eur. J. Biochem, 2003, 270, 1141–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X and Lai R, Chem. Rev, 2015, 115, 1760–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soballe PW, Maloy WL, Myrga ML, Jacob LS and Herlyn M, Int. J. Cancer, 1995, 60, 280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strandberg E, Horn D, Reisser S, Zerweck J, Wadhwani P and Ulrich AS, Biophys. J, 2016, 111, 2149–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedl S, Leber R, Rinner B, Schaider H, Lohner K and Zweytick D, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2015, 1848, 2918–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zachowski A, Biochem. J, 1993, 294, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camilio KA, Rekdal Ø and Sveinbjörnsson B. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e29181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan SC, Hui L and Chen HM, Anticancer Res, 1998, 18, 4467–4474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Huang R, Jin JM, Zhang LJ, Zhang H, Chen HZ, Chen LL and Luan X. Front. Chem, 2020, 8, 519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang ZQ, An HW, Hou DY, Wang MD, Zeng XZ, Zheng R, Wang L, Wang KL, Wang H and Xu WH, Adv. Mater, 2019, 31, e1807175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genovese I, Ilari A, Assaraf YG, Fazi F and Colotti G, Drug Resist. Updat, 2017, 32, 23–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters AA, Jamaludin S, Yapa K, Chalmers S, Wiegmans AP, Lim HF, Milevskiy M, Azimi I, Davis FM, Northwood KS, Pera E, Marcial DL, Dray E, Waterhouse NJ, Cabot PJ, Gonda TJ, Kenny PA, Brown MA, Khanna KK, Roberts-Thomson SJ and Monteith GR, Oncogene, 2017, 36, 6490–6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo S, Zhangsun D, Zhu X, Wu Y, Hu Y, Christensen S, Harvey PJ, Akcan M, Craik DJ and McIntosh JM, J. Med. Chem, 2013, 56, 9655–9663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Qian J, Sun ZH, Zhangsun DT and Luo SL, Mar. Drugs, 2019, 17, 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian J, Liu YQ, Sun ZH, Zhangsun DT and Luo SL, Eur. J. Phrmacol, 2019, 865, 172674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu YF, Pan QX, Meng H, Jiang YS, Mao AQ, Wang T, Hua D, Yao XQ, Jin J and Ma X, Pharmacol. Res, 2015, 93, 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand P, Grigoryan A, Bhuiyan MH, Ueberheide B, Russell V, Quinonez J, Moy P, Chait BT, Poget SF and Holford M, PLOS One, 2014, 9, e94122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anand P, Filipenko P, Huaman J, Lyudmer M, Hossain M, Santamaria C, Huang K, Ogunwobi OO and Holford M, Mar. Drugs, 2019, 17, 587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon S, Bosmans F, Kaas Q, Cheneval O, Conibear AC, Rosengren KJ, Wang CK, Schroeder CI and Craik DJ, Biotechnol. Bioeng, 2016, 113, 2202–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dave K and Lahiry A, Curr. Top. Med. Chem, 2012, 12, 845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janke C and Magiera MM, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol, 2020, 21, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Risinger AL and Du L, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2020, 37, 634–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luesch H, Moore RE, Paul VJ, Mooberry SL and Corbett TH, J. Nat. Prod, 2001, 64, 907–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang K, Chen B, Gianolio DA, Stefano JE, Busch M, Manning C, Alving K, Gregory RC, Brondyk WH, Miller RJ and Dhal PK, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2019, 17, 8115–8124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenner C and Kroemer G, Science, 2000, 289, 1150–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerkis I, Hayashi MA, Prieto DSA, Pereira A, De Sa JP, Zaharenko J, Radis-Baptista G, Kerkis A and Yamane T, Biomed. Res. Int, 2014, 2014, 675985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fadel V, Bettendorff P, Herrmann T, de Azevedo WJ, Oliveira EB, Yamane T and Wuthrich K, Toxicon, 2005, 46, 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nascimento FD, Sancey L, Pereira A, Rome C, Oliveira V, Oliveira EB, Nader HB, Yamane T, Kerkis I, Tersariol IL, Coll JL and Hayashi MA, Mol. Pharm, 2012, 9, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tansi FL, Filatova MP, Koroev DO, Volpina OM, Lange S, Schumann C, Teichgraber UK, Reissmann S and Hilger I, J. Cell Biochem, 2019, 120, 6528–6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gesell J, Zasloff M and Opella SJ, J. Biomol. NMR, 1997, 9, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerkis I, Hayashi MA, Prieto DSA, Pereira A, De Sa JP, Zaharenko J, Radis-Baptista G, Kerkis A and Yamane T, Biomed. Res. Int, 2014, 2014, 675985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crampton SL, Adams EG, Kuentzel SL, Li LH, Badiner G and Bhuyan BK, Cancer. Res, 1984, 44, 1796–1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alonso-Alvarez S, Pardal E, Sanchez-Nieto D, Navarro M, Caballero MD, Mateos MV and Martin A, Drug Des. Devel. Ther, 2017, 11, 253–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li D, Qin Q, Wang XY, Shi HS, Luo M, Guo FC, Wang W and Wang YS, Oncol. Rep, 2014, 31, 1287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rady I, Siddiqui IA, Rady M and Mukhtar H, Cancer Lett, 2017, 402, 16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laederach A, Andreotti AH and Fulton DB, Biochemistry, 2002, 41, 12359–12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang PM, Zhou N, Shan X, Arrowsmith CH and Vogel HJ, Biochemistry, 1998, 37, 4288–4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seber LE, Barnett BW, McConnell EJ, Hume SD, Cai J, Boles K and Davis KR, PLoS One, 2012, 7, e35409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fahy RJ and Wewers MD, Immunol. Res, 2005, 31, 75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Chen X, Yan YY, Zhu XC, Liu MM and Liu XH, J. Med. Chem, 2020, 63, 3327–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hossain MB, van der Helm D, Antel J, Sheldrick GM, Sanduja SK and Weinheimer AJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 1988, 85, 4118–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potts MB, McMillan EA, Rosales TI, Kim HS, Ou YH, Toombs JE, Brekken RA, Minden MD, MacMillan JB and White MA, Nat. Chem. Biol, 2015, 11, 401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jimenez PC, Wilke DV, Branco PC, Bauermeister A, Rezende-Teixeira P, Gaudencio SP and Costa-Lotufo LV, Br. J. Pharmacol, 2020, 177, 3–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Losada A, Berlanga JJ, Molina-Guijarro JM, Jimenez-Ruiz A, Gago F, Aviles P, de Haro C and Martinez-Leal JF, Biochem. Pharmacol, 2020, 172, 113744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang ZR, Wang L, Liu XS, Chen C, Wang BL, Wang WL, Hu C, Yu KL, Qi ZP, Liu QW, Wang AL, Liu J, Hong GC, Wang WC and Liu QS, Acta Pharm. SIN. B, 2020, 10, 488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sitohy B, Nagy JA and Dvorak HF, Cancer Res, 2012, 72, 1909–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang XL, Jiang AM, Qi BH, Yu H, Xiong YY, Zhou GL, Qin MS, Dou JF and Wang JF, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol, 2018, 102, 4817–4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dinh TT, Kim DH, Luong HX, Lee BJ and Kim YW, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2015, 25, 4016–4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Y, Han MF, Liu C, Liu TY, Feng YF, Zou Y, Li B and Liao HL, RSC Adv, 2017, 7, 17514–17518. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi SL, Wang YY, Liang Y and Li QF, World J. Gastroenterol, 2006, 12, 1694–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen J, Xu XM, Underhill CB, Yang S, Wang L, Chen Y, Hong S, Creswell K and Zhang L, Cancer Res, 2005, 65, 4614–4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vargas CY, Rodriguez GJ, Umana PY, Leal CA, Almanzar RG, Garcia CJ and Rivera MZ, Molecules, 2017, 22, 1641. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheng MJ, Zhao YJ, Zhang AC, Wang LY and Zhang GZ, J. Pept. Sci, 2014, 20, 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi J, Li WS, Lu KJ, Jin FY, Liu D, Xu XL, Wang XJ, Kang XQ, Wang W, Shu GF, Han F, Ying XY, You J, Ji JS and Du YZ, Nano Lett, 2019, 19, 4949–4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernandez-Tome S, Xu F, Han YH, Hernandez-Ledesma B and Xiao H, Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2020, 21, 537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vuyyuri SB, Shidal C and Davis KR, Curr. Opin. Pharmacol, 2018, 41, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piktel E, Niemirowicz K, Wnorowska U, Wątek M, Wollny T, Głuszek K, Góźdź S, Levental I and Bucki R, R. Arch. Immunol Therapiae Exp, 2016, 64, 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaplon H, Muralidharan M, Schneider Z and Reichert JM, mAbs, 2020, 12, 1703531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cancer Discov, 2019, 9, OF2. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaloyannidis P, Hertzberg M, Webb K, Zomas A, Schrover R, Hurst M, Jacob I, Nikoglou T and Connors JM, Br. J. Haematol, 2020, 188, 540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pernas S, Martin M, Kaufman PA, Gil-Martin M, Gomez PP, Lopez-Tarruella S, Manso L, Ciruelos E, Perez-Fidalgo JA, Hernando C, Ademuyiwa FO, Weilbaecher K, Mayer I, Pluard TJ, Martinez GM, Vahdat L, Perez-Garcia J, Wach A, Barker D, Fung S, Romagnoli B and Cortes J, Lancet Oncol, 2018, 19, 812–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liao HW, Garris C, Pfirschke C, Rickelt S, Arlauckas S, Siwicki M, Kohler RH, Weissleder R, Sundvold-Gjerstad V, Sveinbjornsson B, Rekdal Ø and Pittet MJ, Cell Stress, 2019, 3, 348–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang KW, Chen B, Gianolio DA, Stefano JE, Busch M, Manning C, Alving K, Gregory RC, Brondyk WH, Miller RJ and Dhal PK, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2019, 17, 8115–8124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pereira RB, Evdokimov NM, Lefranc F, Valentao P, Kornienko A, Pereira DM, Andrade PB and Gomes N, Mar. Drugs, 2019, 17, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iovanna JL and Closa D, Oncoimmunology, 2017, 6, e1358840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scala S, Clin. Cancer Res, 2015, 21, 4278–4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamazaki T, Pitt JM, Vetizou M, Marabelle A, Flores C, Rekdal Ø, Kroemer G and Zitvogel L, Cell Death Differ, 2016, 23, 1004–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sveinbjornsson B, Camilio KA, Haug BE and Rekdal Ø, Future Med. Chem, 2017, 9, 1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aronson MR, Simonson AW, Orchard LM, Llinas M and Medina SH, Acta Biomater, 2018, 80, 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yu X, Dai YF, Zhao YF, Qi SH, Liu L, Lu LS, Luo QM and Zhang ZH, Nat. Commun, 2020, 11, 1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Araste F, Abnous K, Hashemi M, Taghdisi SM, Ramezani M and Alibolandi M, J. Control. Release, 2018, 292, 141–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jin HL, Wan C, Zou ZW, Zhao GF, Zhang LL, Geng YY, Chen T, Huang A, Jiang FG, Feng JP, Lovell JF, Chen J, Wu G and Yang KY, ACS Nano, 2018, 12, 3295–3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lau YH, de Andrade P, Wu Y and Spring DR, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2015, 44, 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schafmeister CE, Po J and Verdine GL, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2000, 122, 5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carvajal LA, Neriah DB, Senecal A, Benard L, Thiruthuvanathan V, Yatsenko T, Narayanagari SR, Wheat JC, Todorova TI, Mitchell K, Kenworthy C, Guerlavais V, Annis DA, Bartholdy B, Will B, Anampa JD, Mantzaris I, Aivado M, Singer RH, Coleman RA, Verma A and Steidl U, Sci. Transl. Med, 2018, 10, eaao3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu Y, Li YH, Li X, Zou Y, Liao HL, Liu L, Chen YG, Bierer D and Hu HG, Chem. Sci, 2017, 8, 7368–7373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cui HK, Guo Y, He Y, Wang FL, Chang HN, Wang Y, Wu FM, Tian CL and Liu L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 9558–9562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gori A, Wang CI, Harvey PJ, Rosengren KJ, Bhola RF, Gelmi ML, Longhi R, Christie MJ, Lewis RJ, Alewood PF and Brust A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 1361–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Holland-Nell K and Meldal M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2011, 50, 5204–5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gilad Y, Firer M and Gellerman G, Biomedicines, 2016, 4,11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Habault J and Poyet JL, Molecules, 2019, 24, 927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhao H, Qin X, Yang D, Jiang YH, Zheng WH, Wang DY, Tian Y, Liu QS, Xu NH and Li ZG, Cell Death Discov, 2017, 3, 17037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen Y, Xu X, Hong S, Chen J, Liu N, Underhill CB, Creswell K and Zhang L, Cancer Res, 2001, 61, 2434–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Felício MR, Silva ON, Gonçalves S, Santos NC and Franco OL, Front. Chem, 2017, 5, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mishra B, Reiling S, Zarena D and Wang GS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2017, 38, 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nejman D, Livyatan I, Fuks G, Gavert N, Zwang Y, Geller LT, Rotter-Maskowitz A, Weiser R, Mallel G, Gigi E, Meltser A, Douglas DM, Kamer I, Gopalakrishnan V, Dadosh T, Levin-Zaidman S, Avnet S, Atlan T, Cooper ZA, Arora R, Cogdill AP, Khan MAW, Ologun G, Bussi Y, Weinberger A, Lotan-Pompan M, Golani O, Perry G, Rokah M, Bahar-Shany K, Rozeman EA, Blank CU, Ronai A, Shaoul R, Amit A, Dorfman T, Kremer R, Cohen ZR, Harnof S, Siegal T, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Gal-Yam EN, Shapira H, Baldini N, Langille MGI, Ben-Nun A, Kaufman B, Nissan A, Golan T, Dadiani M, Levanon K, Bar J, Yust-Katz S, Barshack I, Peeper DS, Raz DJ, Segal E, Wargo JA, Sandbank J, Shental N and Straussman R. Science 2020, 368, 973–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barata PC and Rini BI. CA Cancer J. Clin, 2017, 67, 507–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]