Abstract

Progress toward an asymmetric synthesis of euphanes is described. A C14-desmethyl euphane systempossessing five differentially substituted and electronically distinct alkenes has been prepared. The route employed is based on sequential metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling, double asymmetric Brønsted acid-mediated intramolecular Friedel–Crafts alkylation, and an oxidative rearrangement to establish the requisite C10 quaternary center. These studies have also led to the discovery of a novel euphane-based modulator of the Liver X Receptor.

Graphical Abstract

Tetracyclic triterpenoids are a large and diverse class of stereochemically complex carbocyclic natural products that continue to stand as challenges for de novo asymmetric synthesis.1 Perhaps most recognizable among such targets are those that possess the lanostane skeleton (Figure 1A),2 as much attention has been directed toward understanding the biosynthesis of lanosterol and its conversion to cholesterol and steroid hormones.3 Classic studies in the area led to development of the Stork–Eschenmoser hypothesis1c,4 and the establishment of an intellectual framework that has enabled the biomimetic synthesis of numerous terpenoid targets through stereocontrolled cation–olefin cyclization processes.1c,5 Despite this rich history in organic chemistry, only a relatively small subset of tetracyclic triteprenoid natural products have yielded to asymmetric synthesis. The euphanes stand as a structurally interesting subclass,2a,6 comprising a molecular skeleton of similar substitution to lanostanes albeit possessing unique stereochemistry. Most notably euphane natural products have distinct stereochemistry at the C13, C14 vicinal quaternary centers (the CD-ring fusion) and also different stereochemical relationships between C13, C17 and C20 that likely impact the preferred orientation of their C17 side chains in three-dimensional space (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Introduction to euphanes and a retrosynthetic strategy based on a sequence of alkoxide-directed metallacycle-mediated annulation, double asymmetric Friedel–Crafts cyclization and oxidative rearrangement.

Here, we describe efforts in chemical synthesis that were designed to address key elements of the unique stereodefined euphane system, particularly with respect to the relative and absolute stereochemistry at C10, C13, C17 and C20. As illustrated in Figure 1B, these studies targeted the construction of the tetracyclic polyunsaturated C14-desmethyl euphane-inspired intermedediate 1. Retrosynthetically, it was reasoned that this target might be accessible from phenol I through an oxidative dearomatization terminated by a group selective Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement.7 In turn, I was imagined as the product of a tandem Brønsted acid-mediated desilylation of the polyunsaturated hydrindane II and subsequent double asymmetric Freidel–Crafts cyclization to establish the C9 stereocenter.7 Finally, hydrindane II was targeted for synthesis from metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling of enyne III with TMS-propyne.7,8 While this coupling technology has been the topic of a number of recent studies,9 an enyne possessing the substitution and unsaturation of III has yet to be demonstrated to be compatible with this type of organometallic coupling process. In addition to describing the chemical synthesis activities that have resulted in the preparation of 1, these efforts have also resulted in the discovery that this C14-desmethyl euphane-like system is a structurally novel agonist of the Liver X Receptor (LXR). While LXR is known to be functionally modulated by a wide variety of ligand types,12 it is notable that 1 has a unique stereodefined natural product-like structure that is structurally distinct from the typical cholestane skeleton found in numerous natural product and natural product-inspired LXR agonists.

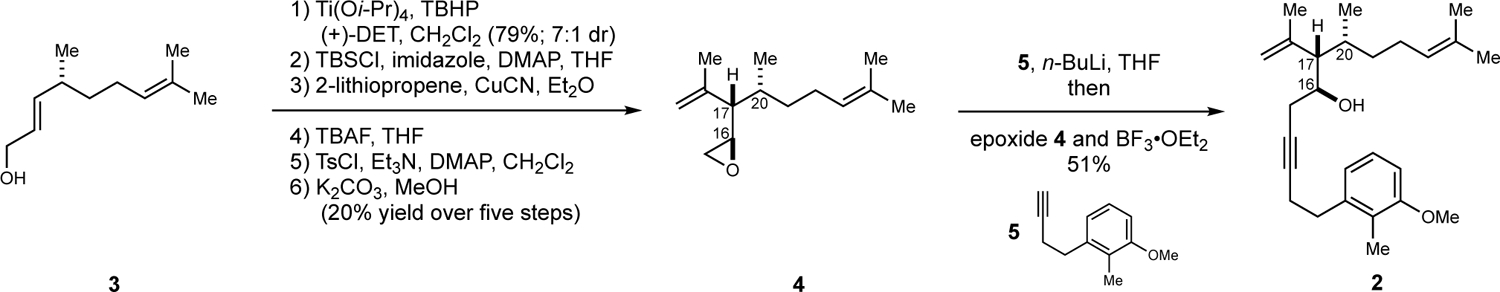

As illustrated in Figure 2, the desired enyne (2) was prepared from the known allylic alcohol 3.13 Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation14 proceeded in 79% yield to deliver a stereodefined disubstituted epoxide with moderate levels of diastereoselection (dr = 7:1). This intermediate (not depicted) was then converted to the stereodefined monosubstituted epoxide 4 through a five-step sequence: (i) silylation of the primary alcohol by the action of TBSCl, (ii) nucleophilic addition of 2-lithiopropene mediated by CuCN, (iii) desilylation using TBAF, (iv) selective activation of the primary alcohol of the resulting diol as its corresponding tosylate, and (v) epoxide formation by treatment with K2CO3. This sequence of steps delivered epoxide 4 in 20% isolated yield over the last five steps of the sequence. Moving forward, coupling of epoxide 4 with alkyne 515 proceeded uneventfully via initial conversion of 5 to its corresponding lithium acetylide and exposure to the combination of BF3•OEt2 and epoxide 4. This final step furnished the fully functionalized and polyunsaturated enyne coupling partner 2 in 51% isolated yield (70% based on recovered 4).

Figure 2.

Construction of enyne 2.

With a stereoselective route to the desired enyne coupling partner in hand, attention was then focused on the key ring-forming reactions presented in the retrosynthetic pathway previously discussed. As depicted in Figure 3, alkoxide-directed metallacycle-mediated [2+2+2] annulation between enyne 2 and TMS-propyne proved effective, delivering a highly functionalized hydrindane intermediate (B) presumably by way of the metallacyclopentadiene A that is thought to undergo chemo- and stereoselective intramolecular [4+2] cycloaddition with the 1,1-disubstituted alkene and chelotropic extrusion of the metal from the resulting organometallic intermediate.8a–b From a practical perspective, the decision was made to move the crude hydrindane product of this annulation reaction (B) forward through the Brønsted acid-mediated tandem protodesilylation and double asymmetric Friedel–Crafts cyclization. As illustrated, exposure to the complex formed from (S)-BINOL and SnCl4 resulted in regio- and stereoselective cyclization and delivered the tetracyclic species 6 in 44% isolated yield (no evidence was found for the production of a stereoisomeric product from this sequence of reactions). Surprisingly, but uneventfully, a small amount of the C24–C25 hydration product of 6 was also isolated from this two-step sequence (6’; 9% – not depicted).

Figure 3.

Coupling of enyne 2 with TMS-propyne and conversion to the euphane-inspired system 1.

Moving forward, we selected to employ what has become standard conditions in our laboratory for demethylation of the C3 methyl ether in numerous synthesis campaigns targeting tetracyclic terpenoid structures — DIBAL in PhMe at reflux.7,15 Unfortunately, in the present case, this procedure for demethylation resulted in the generation of a significant amount of product where the trisubstituted alkene formerly present in the C17 side chain was reduced (7:8 = 1:1.5). While numerous other methods for demethylation are available that could avoid this undesired reduction of the side chain,16 the mixture of products from this reductive demethylation was advanced through the oxidative rearrangement reaction. As depicted at the bottom of Figure 3, the final two-step sequence proceeded with reasonable efficiency and delivered a mixture of dienone products (1 and 9) in 54% yield.

Compound 1 was separated from the overreduced species 9 and fully characterized. Notably, 1 possesses a variety of molecular features of potential interest in total synthesis campaigns: (1) it contains the desired stereodefined and unsaturated side chain at C17 that is found in scores of terpenoid natural products, (2) it has the anti- relative stereochemistry between the C10 and C13 quaternary centers that is typical of euphane and limonoid natural products, and (3) it possesses five distinct olefins that are expected to be capable of undergoing selective reactions with a wide variety of reagents. Regarding future efforts for accomplishing de novo asymmetric syntheses of euphanes based on the foundation of chemistry described here, the primary challenge remains the selective installation of the requisite quaternary center at C14. Future studies will be focused on this problem and will be reported in due course.

Notably, the C14-desmethyl euphane 1, while not a known natural product, bears some structural resemblance to numerous natural and semisynthetic modulators of the Liver X Receptor (LXR), as well as numerous sterol intermediates in the mammalian biosynthetic pathway to cholesterol (e.g., FF-MAS, T-MAS, and zymosterol, among others),3 despite having fundamentally distinct stereochemistry at C13 and C17, and possessing a C3 ketone rather than the typical β-OH.12,17 LXR has been a target of great interest in the pharmaceutical industry for nearly twenty years, with selective agonism thought to be a viable means to achieve novel therapeutic interventions for a wide variety of indications that include atherosclerosis, inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Unfortunately, potent small molecule agonists of this receptor (not sterol in nature) typically result in triggering undesired cellular pathways that cause lipogenesis and hepatic steatosis.10,11 As such, no pharmaceutical agent targeting LXR has been successfully advanced through clinical trials to approval.

Interestingly, while the tetracycles prepared here are structurally related to cholestane-based LXR agonists, their stereochemistries, and hence, three-dimensional shapes are distinct. These structural differences manifest from the unique C10-C13 “anti-” relative stereochemistry that alters the shape of the carbocyclic core skeleton, and the stereochemistry at C17 that is opposite to that encountered in cholestane-based LXR agonists. With curiosity leading the way, a number of the tetracyclic sterol-like agents synthesized were evaluated for their ability to modulate LXR.

The nuclear receptor LXR exists as two isoforms (LXRα [NR1H3] and LXRβ [NR1H2]). LXRβ is very widely expressed while LXRα is much more limited to tissues such as the liver. We assessed the ability of some of the compounds prepared in this effort to bind to the ligand binding domains (LBDs) of both LXRα and LXRβ using a radioligand binding assay with the tritiated synthetic non-steroidal LXR agonist 3H-T090131710 (Figure 4A). As illustrated in Figure 4B, unlabeled T0901317 displayed the highest affinity with a Ki of 0.13 μM (LXRα) and 0.10 μM (LXRβ). 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-OHC), a naturally occurring steroidal LXR agonist,11d displayed a Ki of 4.0 and 6.9 μM at LXRα and LXRβ, respectively. Notably, several of the novel tetracyclic compounds prepared here also displayed similar potency to 25-hydroxycholesterol with LXR potencies ranging from 2.1 to 13 μM (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of synthetic tetracycles as ligands to LXRα and LXRβ, and functional evaluation of 1 on gene expression induced by selective agonism of LXR. A) Chemical structures of compounds evaluated for binding to LXRα and LXRβ. B) Results of radioligand binding assays for LXRα and LXRβ using 3H-T0901317 as a radioligand and compounds from (A) as cold competitors. Ki values are indicated in μM. C) Evaluation of the ability of 1 to modulate LXR target genes in the human THP-1 monocytic cell line – concentrations compounds tested: T0901317 (10 μM), 25-hydroxycholesterol (10 μM), 1 (0.01 μM, 0.1 μM, and 1 μM). ABCA1, ATP binding cassette subfamily A Member 1.

The most potent compound, tetracycle 1 (2.1 μM (LXRα) and 2.4 μM (LXRβ)), was assessed for cell based activity in the human monocytic THP-1 cell line for its ability to modulate expression of a well-characterized LXR target gene, ABCA1, which is a critical regulator of cholesterol efflux. As has been previously described, the non-steroidal LXR agonist T0901317 (at 10 μM) is an effective LXR agonist increasing the expression of ABCA1 (Figure 4C). As anticipated, the steroidal LXR agonist 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-OHC; at 10 μM) increased the expression of ABCA1 as well, albeit at lower levels than T0901317. Importantly, compound 1 also increased ABCA1 expression in a dose-dependent manner (administered at 0.01 μM, 0.1 μM, and 1 μM) consistent with this compound functioning as an agonist of LXR.

Overall, these studies describe progress toward establishing a de novo asymmetric synthesis pathway to euphanes. Efforts have resulted in demonstrating that metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling is effective with an enyne substrate that contains a sterol-like unsaturated side chain. The highly functionalized hydrindane intermediate generated from the metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling was successfully advanced by way of tandem Brønsted acid-mediated protodesilylation and double asymmetric Freidel–Crafts cyclization followed by oxidative dearomatization/Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement. Overall, this sequence of chemical transformations furnished the complex tetracyclic dienone 1 in just four steps from the enyne coupling partner 2. It is understood that lingering challenges associated with the use of this foundation of chemistry to access euphanes include installation of the C14 quaternary center, and accomplishing this goal is the focus of ongoing studies. Nevertheless, it was recognized that the stereochemically defined tetracyclic compounds produced in these studies have molecular features related to steroidal LXR agonists, albeit having subtly different three-dimensional shapes. Following up on this recognition, the C14-desmethyl euphanes produced in this study were studied as potential functional ligands of LXR. Notably, 1 emerged as the most potent synthetic natural product-like LXR agonist that, while possessing only modest potency, has similar properties to 25-hydroxycholesterol. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a selective modulator of LXR based on structural features of a euphane.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

We gratefully acknowledge financial support of this work by the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS, NIMH, and NIA).

Funding Source

The National Institutes of Health – (GM134725 to GCM, and MH092769, AG060769 to TPB)

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Procedures for chemical synthesis and ligand evaluation as well as spectroscopic data (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES:

- (1).(a) Hanson JR Steroids: partial synthesis in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Prod. Rep 2010, 27, 887–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Covey DF ent-Steroids: novel tools for studies of signaling pathways. Steroids, 2009, 74, 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoder RA; Johnston JN A case study in biomimetic total synthesis: polyolefin carbocyclizations to terpenes and sterols. Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 4730–4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zeelen FJ Steroid total synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep 1994, 11, 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Mackay EG; Sherburn MS The Diels–Alder reaction in steroid synthesis. Synthesis, 2015, 1–21. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kaplan W; Khatri HR; Nagorny P Concise enantioselective total synthesis of cardiotonic steroids 19-hydroxysarmentogenin and trewianin aglycone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7194–7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nising CF; Bräse S Highlights in steroid chemistry: total synthesis versus semisynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 9389–9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Ishihara K; Nakamura S; Yamamoto H The first enantioselective biomimetic cyclization of polyprenoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 4906–4907. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For recent examples, see:; (a) Hill RA; Connolly JD Triterpenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep 2020, 37, 962–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Isaka M; Chinthanom P; Vichai V; Sommai S; Choeyklin R Ganoweberianones A and B, antimalarial lanostane dimers from cultivated fruiting bodies of basidiomycete Ganoderma weberianum. J. Nat. Prod 2020, 83, 3404–3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jaitheerapapkul S; Kuhakarn C; Hongthong S; Anantachoke N; Thanasansurapong S; Chairoungdua A; Suksen K; Nuntasaen N; Reutrakul V Lanostane derivatives from the leaves and twigs of Garcinia wallichii. Phytochem. Lett 2020, 38, 101–106. [Google Scholar]; (d) Isaka M; Sappan M; Choowong W; Boonpratuang T; Choeyklin R; Feng T; Liu J-K Antimalarial lanostane triterpenoids from cultivated fruiting bodies of the basidiomycete Ganoderma sp. J. Antibiotics, 2020, 73, 702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pailee P; Kruahong T; Hongthong S; Kuhakarn C; Jaipetch T; Pohmakotr M; Jariyawat S; Suksen K; Akkarawongsapat R; Limthongkul J; Panthong A; Kongsaeree P; Prabpai S; Tuchinda P; Reutrakul V Cytotoxic, anti-HIV–1 and anti-inflammatory activities of lanostanes from fruits of Garcinia speciosa. Phytochem. Lett 2017, 20, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- (3).For a recent review, see:; Nes DW Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem. Rev 2011, 11, 6423–6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Stork G; Burgstahler AW The stereochemistry of polyene cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1955, 77, 5068–5077. [Google Scholar]; (b) Eschenmoser A; Ruzicka L; Jeger O; Arigoni D Zur kenntnis der triterpene. Eine stereochemische interpretation der biogenetischen isoprenregel bei den triterpenen.. Helv. Chim. Acta, 1955, 1890–1904. [Google Scholar]; For a recent review, see:; (c) Eschenmoser A; Arigoni D Revisited after 50 years: The ‘stereochemical interpretation of the biogenetic isoprene rule for the triterpenes’. Helv. Chim. Acta, 2005, 88, 3011–3050. [Google Scholar]

- (5).For a recent review, see:; (a) Barret AGM; Ma T-K; Mies T Recent developments in polyene cyclizations and their applications in natural product synthesis. Synthesis, 2018, 50, A–P. [Google Scholar]; For a recent example, see:; (b) Du K; Guo P; Chen Y; Cao Z; Wang Z; Tang W Enantioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Dearomative Cyclization for the Efficient Synthesis of Terpenes and Steroids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 3033–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).For recent examples, see:; (a) Hou Y; Cao S; Brodie PJ; Miller JS; Birkinshaw C; Andrianjafy MN; Andriantsiferana R; Rasamison VE; TenDyke K; Shen Y; Suh EM; Kingston DG Euphane triterpenoids of Cassipourea lanceolata from the Madagascar rainforest. Phytochem. 2020, 71, 669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Silva VAO, et al. Euphol, a tetracyclic triterpene, from Euphorbia tirucalli induces autophagy and sensitizes temozolomide cytotoxicity on glioblastoma. Inv. New Drugs, 2019, 37, 223–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kim WS, Shalit ZA; Nguyen SM; Schoepke E; Eastman A; Burris TP; Gaur AB; Micalizio GC A synthesis strategy for tetracyclic terpenoids leads to agonists of ERβ. Nature Commun. 2019, 10, 2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).For other examples of this type of annulation reaction, see:; (a) Greszler SN; Reichard HA; Micalizio GC Asymmetric synthesis of dihydroindanes by convergent alkoxide-directed metallacycle-mediated bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2766–2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeso V; Aquino C; Cheng X; Mizoguchi H; Nakashige M; Micalizio GC Synthesis of angularly substituted trans-fused hydroindanes by convergent coupling of acyclic precursors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8209–8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim WS; Aquino C; Mizoguchi H; Micalizio GC LiOOt-Bu as a terminal oxidant in a titanium alkoxide-mediated [2+2+2] reaction cascade. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 3557–3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mizoguchi H; Micalizio GC Synthesis of highly functionalized decalins via metallacycle-mediated cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6624–6628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Mizoguchi H; Micalizio GC Synthesis of angularly substituted trans-fused decalins through a metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 13099–13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Aquino C; Greszler SN; Micalizio GC Synthesis of the cortistatin pentacyclic core by alkoxide-directed metallacycle-mediated annulative cross-coupling. Org. Lett 2016, 18, 2624–2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim WS; Du K; Easman A; Hughes RP; Micalizio GC Synthetic nat- or ent-steroids in as few as five chemical steps from epichlorohydrin. Nature Chem. 2018, 10, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wai HT; Du K; Anesini J; Kim WS; Eastman A; Micalizio GC Synthesis and discovery of estra-1,3,5(10),6,8-pentaene-2,16α-diol. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 6220–6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shalit ZA; Valdes LC; Kim WS; Micalizio GC From an ent-estrane, through a nat-androstane, to the total synthesis of the marine-derived Δ8,9-pregnene (+)-03219A. Org. Lett 2021, 23, 2248–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Schultz JR, Tu H; Luk A; Repa JJ; Medina JC; Li L; Schwendner S; Wang S; Thoolen M; Mangelsdorf DJ; Lustig KD; Shan B Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2831–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Quinet EM; Savio DA; Halpern AR; Chen L; Miller CP; Nambi P Gene-selective modulation by a synthetic oxysterol ligand of the liver X receptor. J. Lipid Res 2004, 45, 1929–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu S; Li S; Henke A; Muse ED; Chang B; Welzel G; Chatterjee AK; Wang D; Roland J; Glass CK; Tremblay M Dissociated sterol-based liver X receptor agonists as therapeutics for chronic inflammatory diseases. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 2570–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Muse ED; Yu S; Edillor CR; Tao J; Spann NJ; Troutman TD; Seidman JS; Henke A; Roland JT; Ozeki KA; Thompson BM; McDonald JG; Bahadorani J; Tsimikas S; Grossman TR; Tremblay MS; Glass CK Cell-specific discrimination of desmosterol and desmosterol mimetics confers selective regulation of LXR and SREBP in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2018, 115, E4680–E4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Janowksi BA; Grogan MJ; Jones S; Wisely B; Kliewer SA; Corey EJ; Mangelsdorf DJ Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRα and LXRβ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1999, 96, 266–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Komati R; Spadoni D; Zheng S; Sridhar J; Riley KE; Wang G Ligands of therapeutic utility for the Liver X Receptors. Molecules, 2017, 22, 22010088 (doi:10.3390).. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).The precursor to 3 is the known aldehyde:; Nozawa D; Takikawa H; Mori K Synthesis and absoluted configuration of stellettadine A: A marine alkaloid that induces larval metamorphosis in ascidians. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2001, 11, 1481–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Katsuki T; Martin VS Asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols: The Katsuki–Sharpless epoxidation reaction. Org. React 1996, 48, 1–299. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hilscher J-C Steroid ether splitting. US 3,956,348, United States Patent and Trademark Office (1975). [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wuts PGM; Greene TW Greene’s Protective Groups in Organic Synteis, Fourth Edition, 2007, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 1082. [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Guillemot-Legris O; Muccioli GG The oxysterome and its receptors as pharmacological targets in inflammatory diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol 2021, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiebl V; Ladurner A; Latkolik S; Dirsch VM Natural products as modulators of the nuclear receptors and metabolic sensors LXR, FXR and RXR. Biotech. Adv 2018, 36, 1657–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.