Abstract

Family caregivers provide vital assistance to older adults living with dementia. An accurate assessment of the needs of caregivers supports the development and provision of appropriate solutions to address these needs. This review of systematic reviews analyzes and synthesizes the needs identified by family caregivers. We conducted a systematic review of systematic reviews using the AMSTAR guideline. Electronic databases were searched for systematic reviews on the needs of caregivers in the context of dementia using a combination of keywords and medical subject headings. Records resulting from the search were screened by two reviewers. Data on the needs of caregivers were extracted from the articles and analyzed using a narrative synthesis approach. Out of the 17 potentially eligible systematic reviews obtained initially, 6 met the inclusion criteria. In total, 20 main needs were identified in the reviews included in this study. The need for information and social support were prominent in this review. Factors such as gender, resources available to the caregiver and the care recipient’s health status may influence caregivers’ needs. Interventions can be tailored toward addressing the most prominent needs of caregivers such as adequate information and resources and available programs may further accommodate and offer need-tailored support to them.

Keywords: Caregivers, Needs, Dementia, Family, Older adults

Introduction

As life expectancy increases globally, the pattern and distribution of diseases is also changing with more people are being diagnosed with dementia than ever before and older adults with dementia requiring assistance from unpaid family caregivers including relatives, friends, or neighbors (Alzheimer Association 2015; McKeown 2009; Stevens et al. 2009). Family caregivers provide vital assistance to older adults living with dementia, supporting them to live safely in the community and reducing the cost of formal healthcare (Boger et al. 2014; Schulz and Eden 2016). Whereas caregivers may derive satisfaction from the tasks they perform, they often have needs arising directly or indirectly from their caregiving duties (Ekwall and Hallberg 2007; Manskow et al. 2017). Due to the terminal and degenerating nature of dementia, these needs are often evolving and may be relative to the health status of the care recipient (Hsieh et al. 2015; Wawrziczny et al. 2017). As the nature or level of disability changes, the needs experienced may change. Other intrinsic factors and sociodemographic characteristics associated with the caregiver and the person they assist could affect the needs that are important to caregivers. Thus, needs may change depending on the condition of the person receiving care or the situation of the caregiver (Zwaanswijk et al. 2013).

Caring for someone with dementia may involve challenges that are different from those experienced in other caregiving situations. For example, a US survey of 1500 caregiving households found that caregivers of people living with dementia provided help for longer hours and had significantly greater levels of stress and caregiver burden than those who provide care to people without dementia (Ory et al. 1999; Roche 2009). Caregivers of people with dementia often experience overlapping physical, mental, and social health issues that may be difficult to isolate and address (Adelman et al. 2014). Poor health status among caregivers of people with dementia has been associated with increased duration of care, assistance with complex needs, and the extent of disability of the care recipient (Schulz and Eden 2016). In addition, research has shown that perceived caregiving burden has an inverse association with the quality of life and health of caregivers. The burden of caregiving has been strongly linked with poor physical and psychological wellbeing among caregivers caring for older adults with dementia (Laks et al. 2016; Mortenson et al. 2015). Therefore, it is important to find ways of relieving the burden of caregiving in the context of dementia. Identifying and addressing the needs experienced by caregivers can be an effective way of reducing their perceived burden.

The needs of caregivers are dependent on a range of factors, not simply the diagnosis of the people they assist. The caregiving needs are influenced by caregivers’ personal attributes and the resources available to them. The interconnected nature of social attributes such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and support networks of caregivers also determine their needs (Johl et al. 2016; Schulz and Sherwood 2008). Likewise, the psychological resilience and human agency of the caregiver may play important roles in determining what they require, and which needs are prioritized (Donnellan et al. 2015). Furthermore, caregiver needs are often a result of the complex interplay of activities that the caregiver performs. People are likely to be more stressed the more they juggle different tasks at the same time. The level of stress experienced by caregivers may therefore determine the needs that they identify at any moment. Hence, different coping methods developed by the caregiver over their life course could make a difference in how burdened they feel as they manage the caregiving process (Papastavrou et al. 2011). Similarly, moderators including resources like healthcare, accessible housing, and funding available to caregivers and the people they assist may also influence the extent to which they feel burdened and the type of further assistance they might require.

Identifying the needs of caregivers is an important step toward addressing those needs. In developing interventions to help caregivers, focusing on the intersections of the various factors affecting their needs is of great importance as the solutions could as well be efficiently designed to address those specific factors. (Wever et al. 2008). However, involving caregivers in a process that identifies their needs should precede the development of interventions to meet caregiving needs (Mortenson Routhier et al. 2017). Although several studies have focused on the needs of family caregivers and some systematic reviews have been completed on this topic, no attempt has been made to synthesize them. Different publications on caregiver needs have used different approaches with some focusing on specific categories of caregivers such as children or spouses. There is a need to explore caregivers’ needs in a holistic manner and put them in context. Understanding the complete area of research on caregiver needs in dementia care, the interconnectivity of various determining factors may assist in the development of solutions to support people with dementia and their caregivers. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of existing systematic reviews with two objectives: (1) to identify the needs of family caregivers of older adults with dementia, and (2) to synthesize these needs based on commonalities across different reviews.

Methods

For this systematic review, the AMSTAR guidelines and the methodological steps described by Smith et al. (Smith et al. 2011) were followed. The study protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42018105657) after a search to confirm a similar systematic review had not been registered. The following questions guided this systematic review:

What are the needs of family caregivers of older adults with dementia?

What are some of the factors influencing caregiving needs?

Search method and criteria for inclusion of systematic reviews

The focus was on systematic reviews on the needs of family caregivers in the context of dementia. The literature search followed the PICO process (Smith et al. 2011), considering the Population of interest (family caregivers of people with dementia) and the Outcome (needs) (see Table 1). Due to the nature of the outcome considered in this review, there was no consideration for intervention and control, the other two components of the PICO structure. Search terms used were MeSH subject headings, descriptors, and keywords describing the needs of family caregivers of older adults living with dementia. For the Population of interest, search terms included “family caregivers”, “informal carers”, “older adults”, “aged”, “elderly”, “dementia”, “dementia”. For the outcome, search terms included MeSH subject headings, descriptors, and keywords describing the areas of need of caregivers such as “needs”, “help” or “solution”. As the study design was restricted to systematic reviews, the term ‘systematic review’ was added to the search strategy to reflect the inclusion criteria developed to meet the study objectives.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| PICO categories | Search terms* |

|---|---|

| Population: family caregivers of older adults with dementia | 1. caregivers/ |

| 2. family/or adult children/ or exp family characteristics/ or exp nuclear family/ | |

| 3. 1 and 2 | |

| 4. (caregiver* or care giver* or carer*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | |

| 5. (family or families or relative* or father* or mother* or sibling* or parent* or spouse* or husband* or wife or wives).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | |

| 6. 4 and 5 | |

| 7. 3 or 6 [FAMILY CAREGIVERS] | |

| 8. exp aged/or exp “aged, 80 and over”/or exp frail elderly/ or exp middle aged/ | |

| 9. (elder* or frail elder* or older adult* or middle age* or senior or seniors).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | |

| 10. 8 or 9 | |

| 11. exp dementia/or exp aids dementia complex/or exp Alzheimer disease/or exp dementia, vascular/or exp dementia, multi-infarct/or exp diffuse neurofibrillary tangles with calcification/or exp frontotemporal lobar degeneration/or exp frontotemporal dementia/ or exp “pick disease of the brain”/or exp primary progressive nonfluent aphasia/ | |

| 12. (dementia*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | |

| 13. 11 or 12 | |

| 14. 10 and 13 [OLDER ADULTS and DEMENTIA] | |

| Outcome: needs of family caregivers | 15. exp health personnel/or exp physical needs, psychological/or exp harm reduction/or exp mental health/or exp accident prevention/or exp safety/or exp patient safety/ |

| 16. exp respite care/ or exp time/ | |

| 17. (need* or help or solution* or security or information or care or fund* or finance* or surveil*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | |

| 18. 15 or 16 or 17 [OUTCOME] | |

| 19. 7 and 14 [FAMILY CAREGIVERS and OLDER ADULTS and NCDs] | |

| 20. 18 and 19 [FAMILY CAREGIVERS and OLDER ADULTS and NCDs and OUTCOME] | |

| Limited to study design: systematic reviews | 21. systematic review*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 22. 20 and 21 |

GSS *mp, pt, tw are abbreviations identifying specific fields in the OVID™ MEDLINE database—e.g., mp = title, abstract, original title, subject heading word, keyword heading word, unique identifier. The/after each term is used in OVID™ MEDLINE for a MESH term search; the ‘exp’ abbreviation signifies the automatic expansion of a MeSH term to its sub-headings

Five electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane library were searched from inception to 06 January 2020 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Literature search: databases and details of numbers of records retrieved

| Date/time | Database | # Records retrieved (including duplicates) | # Records retrieved (excluding duplicates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 07 January 2020 00:05 | Ovid MEDLINE(R) and In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to January 06, 2020 | 96 | 84 |

| 07 January 2020 00:09 | Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print January 06, 2020 | 1 | 1 |

| 07 January 2020 00:12 | EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to December 27, 2019, ACP Journal Club 1991 to November 2019, Cochrane Clinical Answers November 2019, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects 1st Quarter 2016 | 192 | 99 |

| 07 January 2020 00:41 | Embase 1974 to 2020 January 03 | 114 | 57 |

| 07 January 2020 01:35 | PsycINFO | 52 | 0 |

| 07 January 2020 02:21 | CINHAL | 51 | 1 |

| Total | 506 | 242 |

The articles resulting from the search were reviewed and screened by two reviewers (OA and MLB) at two levels: (1) using title and abstract to find potentially relevant reviews and exclude articles that are not appropriate; (2) full articles of potentially relevant titles were obtained and reviewed to determine papers that met the inclusion criteria.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria for including a review were:

Published in peer-reviewed academic journals.

Study design is a systematic review

In English or French.

Study about the needs of family caregivers of people with dementia.

Exclusion criteria.

Dissertations, conference proceedings

Non-empirical publications (e.g., protocols, and editorials)

The reference lists of pertinent articles were reviewed by title and abstract to identify other potentially relevant systematic reviews.

Selection of reviews

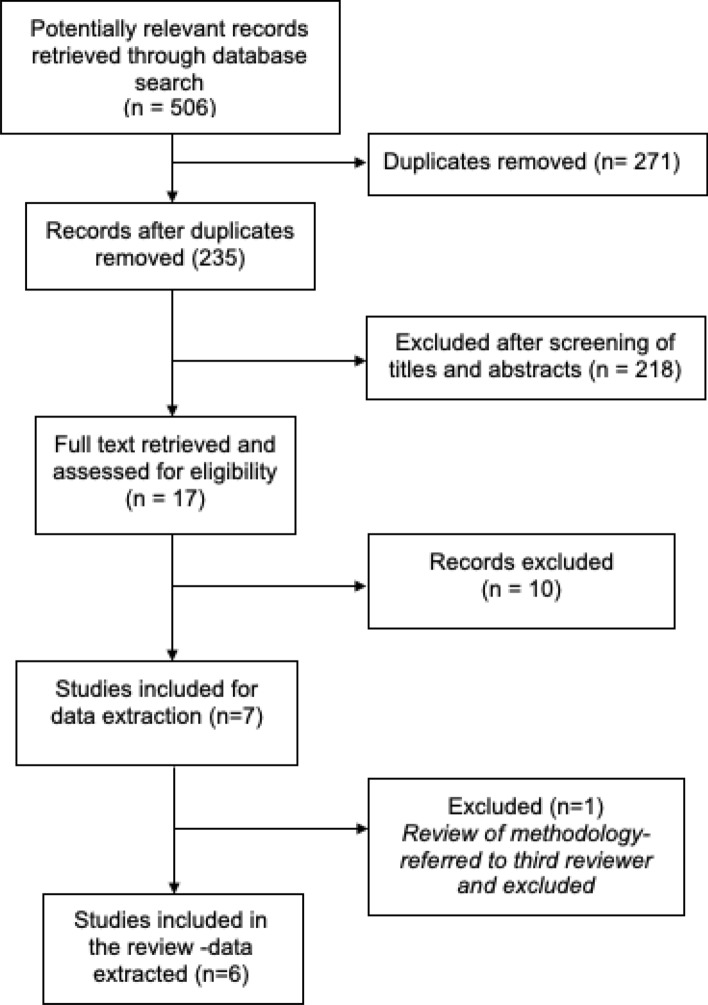

Two reviewers (OA and MLB) screened all the search results, at first based on the title and abstract. Subsequently, two of the authors assessed the full articles of the potentially relevant reviews (Fig. 1). A third reviewer was available to resolve any impasse in case a consensus could not be reached.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of retrieved sources and screening process

Quality assessment of included reviews

The AMSTAR tool for assessing the methodological standard of systematic reviews (Shea et al. 2007) was applied to evaluate the methodological quality of each included article. This tool uses binary scoring such that an item is given a score of 1 if present and 0 if unclear, absent, or not applicable. The AMSTAR tool has 11 criteria against which each systematic review was graded independently by two reviewers (OA and MLB) and conflicts were resolved by discussion between the authors. Assessment of potential bias, such as selection bias, information bias, and confounding, was conducted based on the inclusion criteria after all articles have been screened.

Data extraction and management

An abstraction tool was used to extract relevant data from included systematic reviews. Data on author details, year of publication, search period, databases searched, number of included studies, country of origin, language, and quality assessment tool used was collected. The summary of the main findings in each included review was also collated. The results were compiled using a narrative synthesis approach, an iterative process involving a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies, exploration of relationships in data, and an assessment of the robustness of the synthesis (Lichtner et al. 2014; Popay et al. 2006). Meta-analysis was not carried out due to the nature of the data collected and the heterogeneity between studies. However, we have reported the frequency of needs identified in the systematic reviews. To achieve our second objective, we ranked the needs of caregivers based on the number of times they appeared in the literature, an approach that has been used in previous systematic reviews of published reviews (25).

Results

The search retrieved 506 potentially eligible records (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, we retrieved full texts of 17 systematic reviews for further eligibility assessment. Seven of the retrieved articles met our inclusion criteria out of which six were retained for our review; one article was a review of methodology and did not provide data on the needs of family caregivers. The six included systematic reviews had explored 133 individual articles on the needs of family caregivers of people living with dementia. Table 3 provides details of the 11 excluded reviews while Table 4 provides details of the six included reviews.

Table 3.

List of excluded reviews

| Review | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Novais T, Dauphinot V, Krolak-Salmon P, Mouchoux C. How to explore the needs informal caregivers of individuals with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease or related diseases? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(86):1–18 | Review of methodology. No data on needs of caregivers |

| Martinez-Alcala CI, Pliego-Pastrana P, Rosales-Lagarde A, Lopez-Noguerola JS, Molina-Trinidad EM. Information and Communication Technologies in the Care of the Elderly: Systematic Review of applications aimed at patients with dementia and caregivers. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;3(1): e6 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on an intervention |

| Alves LCS, Monteiro DQ, Bento SR, Hayashi VD, Pelegrini LNC, Vale FAC. Burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2019;13(4):415–421 | No data on needs of caregivers |

| Bull MJ, Boaz L, Jerme M. Educating family caregivers for older adults about delirium: A systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(3):232–40 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on an intervention. Not restricted to the context of dementia care |

| Greenwood N, Smith R. Barriers and facilitators for male carers in accessing formal and informal support: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82(2):162–9 | No data on needs of caregivers. Not restricted to the context of dementia care |

| Wittenberg E, Prosser LA. Disutility of illness for caregivers and families: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(6):489–500 | No data on needs of caregivers. Not restricted to the context of dementia care |

| Del-Pino-Casado R, Frias-Osuna A, Palomino-Moral PA, Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL. Coping and subjective burden in caregivers of older relatives: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(11):2311–22 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on caregiver burden. Not restricted to the context of dementia care |

| Quinn C, Clare L, Woods RT. The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(1):43–55 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on an intervention |

| Peacock SC, Forbes DA. Interventions for caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review. Can J Nurs Res. 2003;35(4):88–107 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on cost of intervention |

| Cooper C, Balamurali TB, Livingston G. A systematic review of the prevalence and covariates of anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(2):175–95 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on mental health issues |

| Cuijpers P. Depressive disorders in caregivers of dementia patients: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):325–30 | No data on needs of caregivers. Focused on mental health issues |

Table 4.

Characteristics of included reviews: data sources and number of studies

| Reference | Search period | Databases searched | Number of included studies | Country of origin | Language | Quality assessment tool used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afram et al. (2015) | Inception—Sept 2013 |

CINAHL Cochrane MEDLINE PsycINFO PubMed Web of knowledge |

13 | Netherlands |

English Dutch German |

Checklist by Bunn et al. (Bunn et al. 2012) |

| Johl et al. (2016) | 2005–2013 |

PsycARTICLES MEDLINE CINAHL PsycINFO Web of knowledge Scopus |

8 | United Kingdom | Not reported | Not reported |

| Khanassov et al. (2016) | Inception—Oct 2014 |

MEDLINE PsycINFO EMBASE |

46 | Canada |

English French Russian |

MMAT |

| McCabe et al. (2016) | 2000–Sept 2015 |

MEDLINE CINAHL PsycINFO Web of Science Scopus |

12 | Australia | English | CASP tool (Long et al. 2020) |

| Millenaar et al. (2016) | Inception—Nov 2013 |

PubMed CINAHL PsycINFO |

27 | Netherlands |

English Dutch French German |

Quality checklists of Mallen et al. (Mallen et al. 2006) and Walsh and Downe (Walsh and Downe 2006) |

| Waligora et al. (2018) | Jan 2000–Feb 2017 |

CINAHL PubMed Web of Science Scopus |

29 | USA | English | Joanna Briggs critical appraisal tool (The Joanna Briggs Institute 2015) |

CASP Critical appraisal skills program; MMAT Mixed methods appraisal tool

The results of this systematic review are structured as follows. First, we briefly summarize the reviews considered at the time of data extraction but excluded for lack of data on the needs of family caregivers. We then describe the methods and tools used for quality assessment in the reviews included in our analysis. Third, we describe the findings of the included reviews, i.e., characteristics (data sources and number of studies), the identified needs of family caregivers. Finally, we summarize the comparative quality assessment of the reviews.

Description of excluded reviews

Of the 11 excluded reviews (Table 3), 10 were excluded because they did not provide data suitable for extraction; there were no data on the needs of family caregivers. Four of these were focused on interventions to address the problems facing family caregivers while two focused on mental health issues affecting them. The reviews varied in length and details of reporting. Four articles were not restricted to caregiving in the context of dementia care (Bull et al. 2016; del-Pino-Casado et al. 2011; Greenwood and Smith 2015; Wittenberg and Prosser 2013). The final review that was excluded (Novais et al. 2017) explored the methodological tools that are used to explore the needs of family caregivers.

Description of included reviews

Six systematic reviews were included in the current study after an extensive search of the five databases from inception to 2020 (Table 4). The number of individual studies included in each systematic review varied from eight (Johl et al. 2016) to 46 articles (Khanassov and Vedel 2016). One systematic review focused on needs during transition from home to institutional care (Afram et al. 2015), one on needs of black and minority ethnic caregivers (Johl et al. 2016), one on the needs of caregivers of people with young-onset dementia (Millenaar et al. 2016), while three focused on needs related to the management of older people with dementia and caregivers’ personal needs in a broad sense (Khanassov and Vedel 2016; McCabe et al. 2016; Waligora et al. 2018). One systematic review (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) retained 46 articles focused on the needs of patients and caregivers and eight on dementia case management but we included this review in the current study due to the large number of articles focused on caregivers. All six systematic reviews included in the current study were conducted in developed countries spread over three continents and all were published in English. In five of the systematic reviews, authors clearly stated that individual articles they included in their reviews were written in English while the sixth review did not report about the language of included articles (Johl et al. 2016).

It was considered whether the systematic reviews included the same articles. In a few instances, the same individual article was included in two different systematic reviews. This overlap affected four of the systematic reviews (Johl et al. 2016; Khanassov and Vedel 2016; McCabe et al. 2016; Millenaar et al. 2016), none of which had more than one overlapping article.

Needs identified in reviews

Methodologies used

The reviews aimed to summarize the needs of family caregivers of people with dementia by providing a comprehensive overview. In all reviews, the needs were either identified and paraphrased from the authors’ description or extracted as verbatim quotes of respondents in the result sections of individual articles. Two reviews applied thematic analysis to generate codes that were then grouped into areas of similarity to generate themes (Afram et al. 2015; McCabe et al. 2016). One review did not describe their approach to analyzing the findings of individual articles (Johl et al. 2016). One article sought needs expressed in other domains assessed by research instruments, such as domains of quality of life (Khanassov and Vedel 2016). Two reviews used a narrative synthesis approach to develop a taxonomy of the identified needs (Khanassov and Vedel 2016; Millenaar et al. 2016), an approach that was followed up with a meta-analysis to evaluate the prevalence of needs in one of the reviews (Khanassov and Vedel 2016). One review used the constant comparison method to synthesize the studies, identifying common themes by finding and comparing the findings in other articles (Waligora et al. 2018).

Settings where the needs were identified

Caregiver needs in dementia were studied in a variety of care settings such as home, hospital, or long-term care facilities (Afram et al. 2015). Authors described caregivers in terms of demographic characteristics with some needs specific to certain target populations including black and ethnic minority groups as well as those caring for people with young-onset dementia (Millenaar et al. 2016).

Description of needs

Authors used different approaches to describe their findings and often described needs in combination with other issues like caregiver attitudes, problems, care management, and experiences with services (Table 5). There was an overlap between some of the identified needs. For example, the need for support in managing care recipients’ activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) could be in form of information, services, or physical help with chores.

Table 5.

Summary of identified needs

| Author/Year | Identified needs |

|---|---|

| Afram et al. (2015) | Knowledge and information about diseases and care options |

| Support from social environments e.g., relatives, peers | |

| Involvement in care planning | |

| Appropriate and adequate formal care | |

| Family involvement in care | |

| Funding for private care | |

| Training in communication skills | |

| To become more prepared for transitioning to long term care | |

| Johl et al. (2016) | Knowledge of support system available in ancestral country of origin |

| Tailored mental health services that address cultural differences and language barriers | |

| Education for families on the nature of dementia | |

| Khannasov et al. (2016) | Earlier diagnosis |

| Education/ counseling on disease | |

| In-home support (for physical care or chores) | |

| Information on relevant services | |

| Help with legal issues | |

| Advising on advance directives | |

| Financial support and planning | |

| Access to family physician and other health professionals trained in geriatrics | |

| Care coordination and continuity of care | |

| Emotional support | |

| Social support | |

| Training in communication skills and strategies for handling maladaptive behaviour | |

| Included in care planning | |

| McCabe et al. (2016) | Information and knowledge |

| Support in managing care recipients’ activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living | |

| (IADL), as well as Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of | |

| Dementia (BPSD) | |

| Appropriate formal care | |

| Informal social support | |

| To have personal challenges (health and general life issues) addressed | |

| Millenaar et al. (2016) | Timely diagnosis |

| Information to better understand disease and type of help available | |

| Waligora et al. (2018) | Sleep |

| Social support and engagement | |

| Participation in leisure activities |

In total, 20 needs were aggregated from the six reviews (Table 6). The description of needs in each review followed the theme/objectives of the paper and depended on the target population. For example, the need for knowledge of the support system available in the ancestral country of origin of the family was identified in a review that focused on minority ethnic groups (Johl et al. 2016).

Table 6.

Summary of how often needs appear in the reviews (in alphabetical order)

| Need | Frequency | References |

|---|---|---|

| Access to family physician and other health professionals trained in geriatrics | 1 | (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Address caregivers’ personal challenges (health and general life issues) | 1 | (McCabe et al. 2016) |

| Advising on advance directives | 1 | (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Appropriate and adequate formal care | 2 | (Afram et al. 2015; McCabe et al. 2016) |

| Care coordination and continuity of care | 2 | (Afram et al. 2015; Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Emotional support | 1 | (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Family involvement in care | 1 | (Afram et al. 2015) |

| Financial support | 2 | (Afram et al., 2015; Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Help with legal issues | 1 | Khanassov Vladimir and Vedel 2016) |

| Included in care planning | 2 | (Afram et al. 2015; Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| In-home support (for physical care or chores) | 1 | (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

| Knowledge and information about diseases and care options | 5 | (Afram et al. 2015; Johl et al. 2016; Khanassov and Vedel 2016; McCabe et al. 2016; Millenaar et al. 2016) |

| Knowledge of support system available in ancestral country of origin | 1 | (Johl et al. 2016) |

| Mental health services that have the competence to address cultural differences and language barriers | 1 | (Johl et al. 2016) |

| Participation in leisure activities | 1 | (Waligora et al. 2018) |

| Sleep | 1 | (Waligora et al. 2018) |

| Support from social environments | 4 | (Afram et al. 2015; Khanassov and Vedel 2016; McCabe et al. 2016; Waligora et al. 2018) |

| Support in managing care recipients’ ADL, IADL, and (BPSD) | 1 | (McCabe et al. 2016) |

| Timely diagnosis | 2 | (Khanassov and Vedel 2016; Millenaar et al. 2016) |

| Training in communication skills | 2 | (Afram et al. 2015; Khanassov and Vedel 2016) |

The need to know about dementia and how to care for a family member living with the disease was the most common need described in five of the reviews (Afram et al. 2015; Johl et al. 2016; Khanassov and Vedel 2016; McCabe et al. 2016; Millenaar et al. 2016). The majority of participants in the individual articles expressed the desire to have adequate information about the diagnosis and the various care options available. Only one review did not mention the need for information (Waligora et al. 2018), likely because this review was focused on the self-care needs of caregivers. In addition, the importance of social support from friends, family, and other caregivers was also frequently identified in the reviews (Afram et al. 2015; McCabe et al. 2016; Waligora et al. 2018).

Other needs were less frequently mentioned when compared to the need for information and social support. Of the other identified needs, two centered around cultural sensitivity and how vital it is to individualize care such that the beliefs and norms of the family are built into their support system (Johl et al. 2016). Caregivers desired to have a good knowledge of the kind of support available in their ancestral country of origin. Caregivers also wanted mental health services that effectively cover their cultural and language preferences. Furthermore, transitioning to care homes seemed to influence the type of needs caregivers prioritize. Needs closely related to care planning and availability of funds were identified in a review addressing the needs of family caregivers during the transition from home toward institutional care (Afram et al. 2015).

In some instances where needs overlap, they have been merged under a single descriptor for the count presented in Table 6. For instance, the need for “funding for private care” and the need for “financial support and planning” have been counted together as “financial support”. Likewise, similar needs have been grouped under three main categories for this synthesis.

Caregiving as gendered role

We explored the place of gender in care provision and how this may relate to the needs of informal caregivers of people with dementia. Only two of the included systematic reviews (Johl et al. 2016; Waligora et al. 2018) provided a gender perspective.

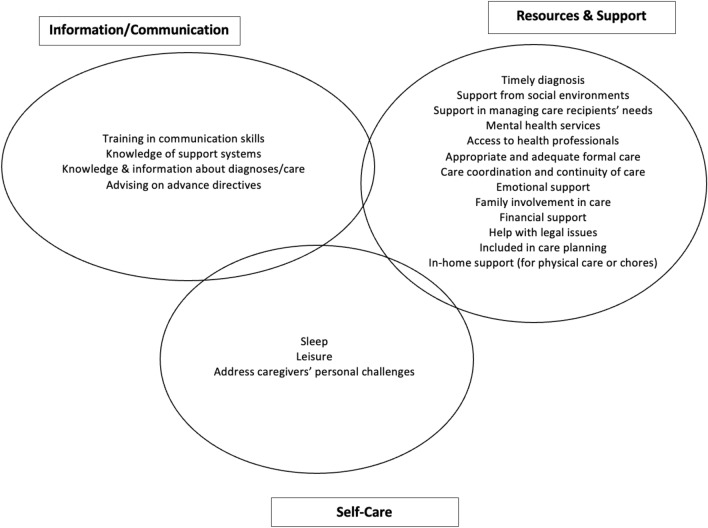

Categories of caregivers’ needs

The needs identified were categorized into three main themes: Information/communication, resources/support, and self-care. These themes were based on similarities of needs and how they are contextualized by caregivers Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Categories of family caregivers’ needs

Quality of included reviews

The AMSTAR tool was used to assess the quality of the systematic reviews (Table 7), Based on the binary scoring, the mean quality score for the included reviews was about 5.83, in the range from 3 (Johl et al. 2016) to 8 (Millenaar et al. 2016).

Table 7.

Summary of quality of systematic reviews

| Reference | Q1. Was an 'a priori' design provided? | Q2. Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Q3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? | Q4. Was the status of publication (i.e., grey literature) used as an Inclusion criterion? | Q5. Was a list of studies (Included and excluded) provided? | Q6. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | Q7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Q8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | Q9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | Q10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Q11. Was the conflict of interest included? | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afram et al. (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Johl et al. (2016) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Khanassov et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| McCabe et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Millenaar et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Waligora et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Mean | 5.83 |

All reviews presented an a priori design and the comprehensive literature search (see Q1 and Q3 in Table 7) but none of them provided full details about the methods used. For instance, none of the reviews stated whether the status of publication was used as an inclusion criterion, provided a list of included and excluded studies, or assessed the likelihood of publication bias (Q4, Q5, and Q10). Two reviews either used a measure of heterogeneity (Khanassov and Vedel 2016) in combining results of different articles (Q9) or mentioned that this test was not applicable (Millenaar et al. 2016). Only one review (Millenaar et al. 2016) clearly stated the conflict of interest and one review was a qualitative synthesis (McCabe et al. 2016) to which Q9 and Q10 were not applicable.

Discussion

This review identified and consolidated the caregiving needs of family caregivers of people with dementia. This is the first systematic review of systematic reviews of the needs of family caregivers in the context of dementia. Our review has brought these needs into focus such that future research may have a targeted approach at developing interventions to address the unmet needs of caregivers (Demers et al. 2016; Mortenson Pysklywec et al. 2017). We developed a preliminary synthesis of the needs of caregivers, described the findings of the included reviews, and explored factors that may be responsible for these needs. The categorization of needs helped highlight main themes or domains that could be considered while addressing caregiver needs. The added advantage is that interventions could be designed to address needs from all the domains without placing too much focus on certain kinds of needs in the same domain at the expense of others. Even as we categorized the identified needs, it was clear that overlaps exist between the different categories. For instance, mental health services could be considered a form of resource as well as self-care for caregivers. Hence, we discuss the individual needs in detail rather than dwell on the categories.

Although several needs were identified in the reviews, the need for information and social support stood out as more prominent. Information needs are diverse and indicate the importance of effective communication between all the professionals involved in the management of the care recipient. For instance, caregivers mostly want access to information about the disease affecting the people they care for and desire to have adequate knowledge of care requirements, expectations, disease progression, and treatment prognosis (Wawrziczny et al. 2017). Adequate information increases caregiver competence, which is one of the main drivers of psychological needs described by the self-determination theory; a framework that conceptualizes human motivation (Dombestein et al. 2019). Caregivers expect to receive helpful information from health professionals as they perform their caregiving tasks. The availability of the health workers when required is seen as vital to reduce frustration and stress on the caregiver (Doser and Norup 2014; Schaaf et al. 2013). A good understanding of the medical condition as well as prognostic expectations supports the caregiver-care recipient relationship. The right information helps caregivers to plan care and anticipating the next stage of disease or care needs of the person they care for makes caregiving tasks less daunting. Having the right information is at the core of caregiving and helping with activities of daily living effectively depends on successful communication. Communication with health professionals is not the only communication need identified; the reviews revealed a common need among family caregivers to adopt better approaches to communication and conflict resolution with their care recipients. In addition to building good relationships with the people they care for, social participation and discussion involving their peers help create a support system for caregivers and their care recipients.

The need for formal and informal social support is consistent in the included reviews. Support from social environments is important for sharing care responsibilities and tasks thereby providing relief to caregivers. The presence of and encouragement from others have been shown to be a boost to caregiver morale (Ducharme et al. 2014; Shanley et al. 2011). Taking a cue from George Herbert Mead’s symbolic interactionism theory that people's purposive and creative selves are social products, it is important that the efforts of caregivers are validated by the people around them (Wladkowski et al. 2020). It is well documented that family caregivers have the desire to be acknowledged and have their needs validated (Ducharme et al. 2014; Wawrziczny et al. 2017). Receiving emotional support from others goes a long way to encourage family caregivers and address some of their psychological needs. Acknowledging and appreciating the sacrifice that family caregivers make can have a positive impact on their mental health. For example, caregivers in a separate focus group study that is not part of the reviews reported that receiving appreciation and acknowledgment from family, friends, and professionals is comforting, providing a feeling that their burden of caregiving is shared (Huis et al. 2018). There is evidence that interventions such as web-based or in-person peer activities like leisure/social groups help alleviate burden as caregivers can share ideas and nurture their psychosocial health (Vaughan et al. 2018; Wakui et al. 2012). Having peers to interact and share ideas with are ways by which family caregivers find respite. Other needs were less frequently mentioned when compared to the need for information and social support. This may be because some of the reviews had a specific focus. For instance, the need for adequate sleep was only identified in the review that focused on the self-care needs of caregivers. Similarly, the need for early dementia diagnosis was described in the reviews that looked at early-onset dementia as well as dementia case management.

Furthermore, access to the various resources that can make caregiving easier or improve the quality of life of caregivers is among the other identified caregiver needs. The presence of appropriate and accessible services or other people to help with practical aspects of caregiving like activities of daily living might allow caregivers to have more time to take care of themselves (Tatangelo et al. 2018; Wawrziczny et al. 2017). Having their physical needs unmet is associated with lower quality of life among caregivers (Dourado et al. 2017; Wawrziczny et al. 2017). Thus, material and human resources including health care professionals who can provide the kind of care indicated were important to caregivers (Doser and Norup 2014; Doyle et al. 2013; Griffiths and Bunrayong 2016; Kim et al. 2018). Similarly, the availability of funds to procure equipment, care services, and programs that may provide respite to caregivers are vital needs. A strong support system has been shown to make caregivers more resilient as explained by the stress-coping theory (Surachman et al. 2018). Available resources help cushion the demands of caregiving, making caregivers more prepared and less pressured by need.

Caregiver needs may differ depending on the gender of the informal caregiver. For instance, previous research had found caregiving to be the responsibility of mostly female carers especially among black and ethnic minority (BME) communities (Jutlla and Moreland 2009). There seems to be an expectation of the daughter or daughter-in-law to provide the care for an aging relative and this presumption is indeed not restricted to BME groups but has also been found to be strong among other communities (Botsford et al. 2012). The gendered nature of caregiving is not an uncommon phenomenon, with an increasing number of females caring for parents and parent in-laws in general (Hirst 2001). How gendered caregiving roles relate to caregiving needs is complex. Women may connect their female identities to caregiving and feel obligated to fulfill society’s gender standards even at the risk of their health (Eriksson et al. 2013). Even when they find it difficult to express, their needs may easily include respite and assistance from other relatives. Research (de la Cuesta-Benjumea 2010; Eriksson et al. 2013) has found that female caregivers were reluctant to accept support because they perceived it as a burden to others or a failure on their part to provide care. Even when they have needs, they are more unlikely to seek help, keep appointments to take care of self or address their personal needs (Wang et al. 2021).

As we pointed out earlier, caregiving needs are fluid, often evolving in the context of care requirements and complexity of the condition of the care recipient and resources available to the caregiver. It is pertinent for health professionals to continue to evaluate whether care management strategies are still appropriate at every phase of care provision. This continuous assessment of care links with the need for appropriate information to be provided to the caregiver as dementia progresses to help caregivers cope with care and avoid the distress generated by poor communication with professionals (Oh 2017). Adequate professional support for caregivers along the continuum of care improves their self-motivation. This autonomous motivation, as described by the self-determination theory, strengthens the stress-coping capacity of caregivers and is further enhanced by a sense of fulfillment that is fostered as they are empowered to provide care in a way that is satisfactory to them (Rigby and Ryan 2018).

The reviews included in the current study were conducted across three continents with no representation of the needs of caregivers in Africa and Asia. This was unintentional but due to the dearth of publications of individual studies on the topic from African and Asian countries. It remains to be seen whether a review of the needs of caregivers of people with dementia in the omitted continents will result in marked changes in the results we presented. Nevertheless, understanding caregiver needs based on geographical location and ethnicity is important (Johl et al. 2016) as it supports the development of culturally sensitive and targeted interventions. Cultural sensitivity in dementia care ensures the ethnic preferences are well understood and respected. Although programs that address cultural peculiarities may be difficult to implement in a multicultural society due to the logistics of securing funding for each culture-specific program, adopting financially affordable options such as the use of peer support/educators who share the same cultural background as the caregiver has been successful (Warshaw and Edelman 2019).

Limitations and future research

There were some limitations to this review. Systematic reviews that were excluded because the language was not English, or French might contain information that might have been contributory to this review. In addition, most of the reviews and individual articles were from developed countries and it is difficult to extend the interpretation of the results to the context of family caregiving in the developing world. Our ranking of needs based on how frequently they were identified in the reviews may be controversial. For instance, needs pertaining to information had the highest frequency but may not necessarily be prioritized above having physical help with chores in the home. Future research on the needs of family caregivers can set out to rank their needs based on priority or order of importance to encourage the development of a focused solution. In addition, it may be more helpful to a future systematic review of caregiver needs if researchers collect data with a uniform questionnaire and utilize a standardized approach to their data analyses.

Conclusion

This review has described the needs of family caregivers of people with dementia based on the findings of six systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria. Some of the needs that were more frequently described such as the information about dementia and available care options were those that pertained directly to the care recipient but if addressed might indirectly provide relief to the caregiver. Interventions that address these needs may not necessarily be focused directly on the caregiver to have the desired effect. Solutions created to assist the care recipient could be meeting the needs of caregivers indirectly. Likewise, social support not only provides relief from the burden of caregiving but also allows caregivers to partake in leisure activities that they may otherwise be unable to enjoy. Our review refines the pool of data available on the needs of family caregivers of people with dementia by highlighting the key aspects of needs that require attention. Bringing the pertinent needs to focus provides a strong platform for programs and policies aimed at providing relevant information, resources, and interventions to address the unmet needs important to family caregivers. Appropriately aimed support programs and interventions are more efficient in addressing the needs of caregivers, improving their quality of life, and enhancing participation in the care of their relatives as they desire. Our findings may guide appropriate, user-centered, and personalized programs that promote the wellbeing of caregivers. Where resources are limited, available solutions, programs, and services may first be targeted at addressing the frequently identified needs and new solutions developed specifically to address unmet needs. Notwithstanding the number of times each need appeared in individual reviews, the expectations of caregivers should be taken into consideration when developing interventions.

Acknowledgments

François Routhier is Research Scholar of the Fonds de la recherche du Québec—Santé.

Funding

None reported.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Matthias Kliegel

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden- a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afram B, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MHC, Hamers JPH. Needs of informal caregivers during transition from home towards institutional care in dementia: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(6):891–902. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association A. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11(3):332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger J, Quraishi M, Turcotte N, Dunal L. The identification of assistive technologies being used to support the daily occupations of community-dwelling older adults with dementia: a cross-sectional pilot study. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014;9(1):17–30. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2013.785035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botsford J, Clarke CL, Gibb CE. Dementia and relationships: experiences of partners in minority ethnic communities. J Adv Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull MJ, Boaz L, Jermé M. Educating family caregivers for older adults about delirium: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2016;13(3):232–240. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F, Goodman C, Sworn K, Rait G, Brayne C, Robinson L, McNeilly E, Iliffe S. Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cuesta-Benjumea C. The legitimacy of rest: conditions for the relief of burden in advanced dementia care-giving. J Adv Nurs. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del-Pino-Casado R, Frías-Osuna A, Palomino-Moral PA, Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL (2011) Coping and subjective burden in caregivers of older relatives: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs 67(11): 2311–2322. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05725.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Demers L, Mortenson WB, Fuhrer MJ, Jutai JW, Plante M, Mah J, Deruyter F. Effect of a tailored assistive technology intervention on older adults and their family caregiver: a pragmatic study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombestein H, Norheim A, Lunde Husebø AM. Understanding informal caregivers’ motivation from the perspective of self-determination theory: an integrative review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1111/scs.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan WJ, Bennett KM, Soulsby LK. What are the factors that facilitate or hinder resilience in older spousal dementia carers? A qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(10):932–939. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.977771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doser K, Norup A. Family needs in the chronic phase after severe brain injury in Denmark. Brain Inj. 2014;28(10):1230–1237. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.915985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourado MCNCN, Laks J, Kimura NRR, Baptista MATAT, Barca MLL, Engedal K, Johannessen A, Tveit B, Johannessen A. Young-onset Alzheimer dementia: a comparison of Brazilian and Norwegian carers’ experiences and needs for assistance. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;33(6):824–831. doi: 10.1002/gps.4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle ST, Perrin PB, Diaz Sosa DM, Espinosa Jove IG, Lee GK, Arango-Lasprilla JC. Connecting family needs and TBI caregiver mental health in Mexico City. Mexico Brain Inj. 2013;27(12):1441–1449. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.826505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme F, Kergoat M-J, Coulombe R, Lvesque L, Antoine P, Pasquier F. Unmet support needs of early-onset dementia family caregivers: a mixed-design study. BMC Nurs. 2014;13(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12912-014-0049-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall AK, Hallberg IR. The association between caregiving satisfaction, difficulties and coping among older family caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(5):832–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson H, Sandberg J, Hellström I. Experiences of long-term home care as an informal caregiver to a spouse: gendered meanings in everyday life for female carers. Int J of Older People Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Smith R. Barriers and facilitators for male carers in accessing formal and informal support: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J, Bunrayong W. Problems and needs in helping older people with dementia with daily activities: perspectives of Thai caregivers. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(2):78–84. doi: 10.1177/0308022615604646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst M. Trends in informal care in Great Britain during the 1990s. Health Soc Care Community. 2001 doi: 10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S, Leyton CE, Caga J, Flanagan E, Kaizik C, Connor CM, Kiernan MC, Hodges JR, Piguet O, Mioshi E. The evolution of caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia with and without amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015 doi: 10.3233/JAD-150475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huis JG, Verkaik R, van Meijel B, Verkade P-J, Werkman W, Hertogh CMPM, Francke AL. Self-Management support and eHealth when managing changes in behavior and mood of a relative with dementia: An asynchronous online focus group study of family caregivers’ needs. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11(3):151–159. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180216-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johl N, Patterson T, Pearson L. What do we know about the attitudes, experiences and needs of Black and minority ethnic carers of people with dementia in the United Kingdom? A systematic review of empirical research findings. Dementia. 2016;15(4):721–742. doi: 10.1177/1471301214534424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutlla K, Moreland N. The personalisation of dementia services and existential realities: understanding Sikh carers caring for an older person with dementia in Wolverhampton. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care. 2009 doi: 10.1108/17570980200900025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanassov V, Vedel I. Family physician–case manager collaboration and needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers: a systematic mixed studies review. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):166–177. doi: 10.1370/afm.1898.INTRODUCTION. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Choi Y, Lee J-H, Jang D-E, Kim S. A review of trend of nursing theories related caregivers in korea. Open Nurs J. 2018;12(1):26–35. doi: 10.2174/1874434601812010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laks J, Goren A, Dueñas H, Novick D, Kahle-Wrobleski K. Caregiving for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and its association with psychiatric and clinical comorbidities and other health outcomes in Brazil. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(2):176–185. doi: 10.1002/gps.4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtner V, Dowding D, Esterhuizen P, Closs SJ, Long AF, Corbett A, Briggs M. Pain assessment for people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews of pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Method Med Health Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2632084320947559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallen C, Peat G, Croft P. Quality assessment of observational studies is not commonplace in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manskow US, Friborg O, Røe C, Braine M, Damsgard E, Anke A, Roe C, Braine M, Damsgard E, Anke A. Patterns of change and stability in caregiver burden and life satisfaction from 1 to 2 years after severe traumatic brain injury: a Norwegian longitudinal study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;40(2):211–222. doi: 10.3233/NRE-161406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M, You E, Tatangelo G. Hearing their voice: a systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist. 2016;56(5):e70–e88. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown RE. The epidemiologic transition: changing patterns of mortality and population dynamics. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3(1 Suppl):19S–26S. doi: 10.1177/1559827609335350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millenaar JK, Bakker C, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ, Kurz A, de Vugt ME. The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/gps.4502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson WB, Demers L, Fuhrer MJ, Jutai JW, Lenker J, De Ruyter F. Development and preliminary evaluation of the caregiver assistive technology outcome measure. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:412–418. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson WB, Pysklywec A, Fuhrer MJ, Jutai JW, Plante M, Demers L. Caregivers’ experiences with the selection and use of assistive technology. Disabil Rehabilit: Assist Technol. 2017 doi: 10.1080/17483107.2017.1353652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson WB, Routhier F, Wister A, Auger C, Fast J, Rushton P, Dalle R, Siebrits M, Atoyebi O, Beaudoin M, Lettre J, Mallette D, Demers L (2017) Typology of family caregiver needs and technological solutions, In: AGE-WELL’s 3rd annual conference.

- Novais T, Dauphinot V, Krolak-Salmon P, Mouchoux C. How to explore the needs of informal caregivers of individuals with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease or related diseases? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(86):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0481-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YS. Communications with health professionals and psychological distress in family caregivers to cancer patients: a model based on stress-coping theory. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;33:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Hoffman RR, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia. Gerontologist. 1999;39(2):177–185. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastavrou E, Tsangari H, Karayiannis G, Papacostas S, Efstathiou G, Sourtzi P. Caring and coping: the dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(6):702–711. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.562178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Baldwin S, Arai L, Britten N, Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Method Programm. 2006 doi: 10.13140/2.1.1018.4643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby CS, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in human resource development: new directions and practical considerations. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2018;20(2):133–147. doi: 10.1177/1523422318756954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roche V. The hidden patient: addressing the caregiver. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337(3):199–204. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31818b114d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf KPW, Kreutzer JS, Danish SJ, Pickett TC, Rybarczyk BD, Nichols MG. Evaluating the needs of military and veterans’ families in a polytrauma setting. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58(1):106–110. doi: 10.1037/a0031693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Eden J (2016). National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Family caregiving roles and impacts. In: Families caring for an aging America. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed]

- Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Supplement):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c.Physical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley C, Russell C, Middleton H, Simpson-Young V. Living through end-stage dementia: The experiences and expressed needs of family carers. Dementia. 2011;10(3):325–340. doi: 10.1177/1471301211407794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Mascarenhas M, Mathers C. Global health risks: progress and challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2009 doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surachman A, Almeida DM, Surachman A, Almeida DM (2018) Stress and coping theory across the adult lifespan. In: Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. 10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.341

- Tatangelo G, McCabe M, Macleod A, You E. “I just don’t focus on my needs”. The unmet health needs of partner and offspring caregivers of people with dementia: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;77:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2015). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Vaughan C, Trail TE, Mahmud A, Dellva S, Tanielian T, Friedman E. Informal caregivers’ experiences and perceptions of a web-based peer support network: mixed-methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2018 doi: 10.2196/jmir.9895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakui T, Saito T, Agree EM, Kai I. Effects of home, outside leisure, social, and peer activity on psychological health among Japanese family caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(4):500–506. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.644263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waligora KJ, Bahouth MN, Han H-R. The self-care needs and behaviors of dementia informal caregivers: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2018;59(5):e565–e583. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D, Downe S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fu Y, Lou V, Tan SY, Chui E. A systematic review of factors influencing attitudes towards and intention to use the long-distance caregiving technologies for older adults. Int J Med Inform. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw H, Edelman D. Building bridges through collaboration and consensus: expanding awareness and use of peer support and peer support communities among people with diabetes, caregivers, and health care providers. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(2):206–212. doi: 10.1177/1932296818807689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrziczny E, Pasquier F, Ducharme F, Kergoat M-J, Antoine P. Do spouse caregivers of young and older persons with dementia have different needs? A comparative study. Psychogeriatri: Offi J Jpn Psychogeriatr Soc. 2017;17(5):282–291. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever R, van Kuijk J, Boks C. User-centred design for sustainable behaviour. Int J Sustain Eng. 2008;1(1):9–20. doi: 10.1080/19397030802166205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E, Prosser LA. Disutility of illness for caregivers and families: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(6):489–500. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0040-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wladkowski SP, Wallace CL, Gibson A. A theoretical exploration of live discharge from hospice for caregivers of adults with dementia. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15524256.2020.1745351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaanswijk M, Peeters JM, van Beek APA, Meerveld JHCM, Francke AL. Informal caregivers of people with dementia: problems, needs and support in the initial stage and in subsequent stages of dementia: a questionnaire survey. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:6–13. doi: 10.2174/1874434601307010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]