Abstract

Objective

To describe tuberculosis epidemiological situation in Brazil, as well as program performance indicators in 2001–2010 period, and discuss the relationship between changes observed and control measures implemented in this century first decade.

Methods

It is a descriptive study, data source was the Information System for Notifiable Diseases (Sinan), Mortality Information System (SIM), Unified Health System Hospital Information System (SIH/SUS) and TB Multidrug-resistant Surveillance System (MDR-TB/SS). Indicators analyzed were organized into four major groups: TB control program (TCP) coverage and case detection; morbidity; treatment and TCP performance; and mortality.

Results

In the years analyzed there was a decrease in the number of new cases and incidence rate, mortality reduction (relative and absolute), and improvement in TB detection and diagnosis, as well in TB/HIV coinfection and drug resistance. However, little progress was found in contact investigation, diagnosis in primary care and TB cure rate.

Discussion

Results showed many advances in tuberculosis control in the 10 years analyzed, but it also points to serious obstacles that need to be solved so Brazil can eliminate tuberculosis as a public health problem.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Epidemiology, Surveillance, Information system, Data quality

Introduction

Although tuberculosis (TB) has an effective treatment for decades, with the resurgence of the disease in the 80s and 90s, as a result of the AIDS epidemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) established TB as a global public health emergency in 1993.

At the time, it was estimated a total of 7–8 million incident cases of TB and 1.3–1.6 million deaths per year worldwide.1 Likewise, recognizing TB as a major global health problem, the United Nations (UN) included tuberculosis in the Millennium Development Goals in 2000. TB is present in the sixth goal and the global targets set for 2015 include reducing the incidence and mortality of the disease by 50% when compared to 1990.

Brazil is of the 22 countries with high burden of the disease worldwide. The number of TB incident cases has decreased on average 1.3% per year in the world since 2002 and mortality was reduced by a third since 1990. If these trends continue, global targets for TB control could be achieved. Brazil has a decreasing trend in incidence rate and according to WHO estimates has reached the goal of start reducing mortality.1

As the main strategy for tuberculosis control, in order to reduce default and death from TB and increase cure, WHO adopted the Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (DOTS). The strategy includes six components: political commitment, case detection by microscopy sputum smear, standardized treatment, directly observed treatment (DOTS), regular and uninterrupted standardized drugs supply and reporting case system.2 This strategy importance is to make treatment outcome not only a patient responsibility, but also a compromise between them and health care system from diagnosis to discharge. Government should make TB control a political priority giving all logistics and strategic conditions necessary in the way.

As tuberculosis became a priority inside the Health Ministry (HM) DOTS strategy and decentralization of TB control to primary care began to strengthen. The increasing national budget, the presence of TB in different instruments of agreement between federal government, states and municipalities, provided increased visibility to TB, both technical and political.

Over the last decade, TB National Control Program (NTP) has been engaged in disseminating morbidity and mortality data from their information systems in publications as the Brazil Health Series, epidemiological bulletins and scientific articles. The intention is subsidize decision-making and adoption of public policies in the three levels of management with information generated from surveillance data. This study aims to describe TB epidemiological and controlling situation in Brazil, in the 2001–2010 period, and discuss the relationship between changes observed and control measures proposed in this century first decade.

Methods

It is a descriptive study of TB notified cases, hospitalizations and deaths occurred in Brazil in the 2001–2010 period.

Data sources used were the Information System for Notifiable Diseases called Sinan-TB (updated on November 2011), the Mortality Information System called SIM, the Unified Health System Hospital Information System called SIH/SUS, the Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Surveillance System called MDR-TB/SS, the Health Establishment National Register and the population bases from the Informatic Department of Unified Health System called Datasus.

The definition of new TB case followed the guidelines included in the Recommendations Manual for Tuberculosis Control in Brazil.3 Qualifications on TB records in Sinan were made by states and municipalities, through out surveillance routines performed, and by national level by checks on information available on national basis.3

Epidemiological and operational TB data were analyzed for the period of 2001–2010, and were aggregated by year of diagnosis, Brazil and Federal Units (FU) of residence. The variables “institutionalized”, “contacts investigated” and “supervised treatment performed” were inserted in Sinan in 2007. For this reason, they were only described after this year.

For data analysis were used the softwares EpiInfo 3.5.2, Microsoft Excel® 2010 and Microsoft Access® 2003. The indicators analyzed were organized into four major groups: TB control programs (TCP) coverage and case detection; morbidity; treatment and PCT performance; and mortality.

TCP coverage and case detection

-

-

Percentage of municipalities which diagnosed TB cases. Case notification was used as a proxy of diagnosis;

-

-

Percentage of TB cases diagnosed in primary care facilities (PCF);

-

-

DOTS coverage in health facilities. The variable “supervised treatment performed” was used to analyze this indicator and WHO's recommended concept of DOTS coverage in the health unit in which the health unit with at least one case in DOTS was accounted for in analysis; and

-

-

TB detection rate for all forms of the disease. WHO's estimate number of cases in Brazil was used for comparison.

Morbidity

-

-

Crude incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants;

-

-

Percentage of TB cases by type input in the information system (new, retreatment and transfers);

-

-

Percentage of new cases by sex, age, race, education, and institutionalization;

-

-

Percentage of new cases according to clinical form;

-

-

Number of cases of MDR-TB; and

-

-

Percentage of TB/HIV cases by total of new cases.

Treatment and TCP performance

-

-

Percentage of smear tests performed by total of new pulmonary cases;

-

-

Percentage of new cases tested for HIV (only the positive and negative cases were accounted, “in process” were discarded);

-

-

Percentage of contacts investigated among contacts identified;

-

-

Percentage of new cases regarding the closer situation;

-

-

Percentage of retreatment cases with sputum culture performed;

-

-

Percentage of new cases on DOTS by total new cases, and

-

-

Number of TB hospitalizations and average admission cost.

Mortality

-

-

Crude TB mortality rate per 100,000 inhabitants. For this indicator analysis were included only deaths that had TB as a primary cause of death.

Results

TCP coverage and case detection

In 2010, 62.2% of Brazilian municipalities diagnosed at least one case, while in 2001 this figure was 48.9%. In 2001, primary care units notified 50.2% (19,181) of new smear positive cases. In 2010, this proportion rose to 56.3% (22,983), representing an annual increase of 2.1% on average in Brazil.

The variable “directly observed treatment performed” was included in Sinan in 2007. For this reason, DOTS coverage was analyzed from this year on. The number of health facilities that perform DOTS in Brazil increased from 1608 in 2006, which represented 30.1% of all units that have reported cases in the country, to 4745 (75.2%) in 2010. This represents an increase of 40.9% on average in the years studied.

The case detection rate in 2001 was 65% while 2010 showed the best value in the series, 88% (Table 1).

Table 1.

TCP coverage and case detection – Brasil, 2001–2010.

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCP coverage | ||||||||||

| Percentage of municipalities which diagnosed TB cases | 48.9 | 60.1 | 62.1 | 62.2 | 64 | 64.2 | 63.1 | 64.1 | 63.7 | 62.2 |

| Percentage of TB cases diagnosed in primary care facilities | 50.2 | 52.0 | 54.1 | 55.1 | 55.6 | 56.9 | 56.2 | 55.6 | 56.7 | 56.3 |

| DOTS coverage in health facilities | – | – | – | – | – | 30.1 | 69.6 | 71.1 | 72.4 | 75.2 |

| Case detection | ||||||||||

| TB detection rate | 65 | 77 | 74 | 83 | 81 | 79 | 78 | 82 | 86 | 88 |

Source: Sinan-TB, WHO.

Morbidity

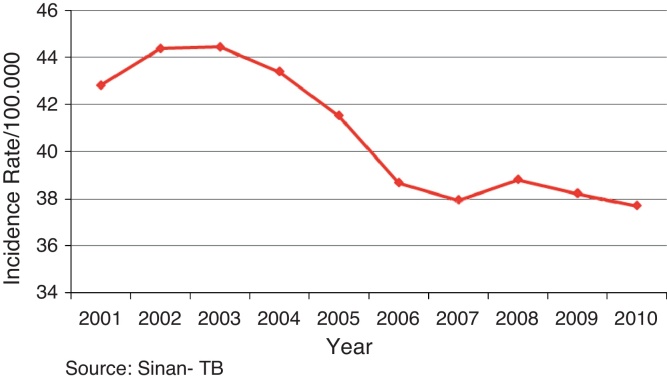

TB incidence in Brazil started to decline in 2003. It occurred a small increase in 2008, and continued to decline after words as seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Tuberculosis crude incidence rate (Sinan-TB) – Brazil, 2001–2010. Source: Sinan-TB.

The incidence rate decreased on average 1.4% annually from 2001 to 2010. This decrease, however, did not occur evenly throughout the period, between regions or FS. In 2001, North and Northeast regions showed the highest incidence rates in the country, 51.2/100,000 inhab. and 46.0/100,000 inhab., respectively. With the exception of southern Brazil, all other regions showed a decline in the incidence rate over the 10 years of study. In 2010, Northern region showed the highest incidence rate in the country (45.7/100,000 inhab.) followed by Southeast (40.7/100,000 inhab.) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of new cases and tuberculosis crude incidence rate (Sinan-TB) – Brazil and state of residence, 2001–2010.

| Federate unit | Number of cases |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Missing | 540 | 682 | 748 | 887 | 821 | 31 | 50 | 59 | 57 | 56 |

| North Region | 6776 | 6890 | 6888 | 7117 | 6942 | 6893 | 6953 | 7014 | 7321 | 7252 |

| Rondônia | 561 | 536 | 548 | 532 | 541 | 448 | 473 | 481 | 571 | 477 |

| Acre | 325 | 305 | 305 | 278 | 267 | 352 | 282 | 274 | 322 | 307 |

| Amazonas | 2273 | 2105 | 2035 | 2135 | 2085 | 2164 | 2274 | 2380 | 2278 | 2360 |

| Roraima | 131 | 145 | 161 | 185 | 130 | 122 | 121 | 136 | 132 | 129 |

| Pará | 3024 | 3278 | 3410 | 3544 | 3477 | 3343 | 3351 | 3338 | 3597 | 3601 |

| Amapá | 194 | 252 | 211 | 224 | 230 | 230 | 244 | 233 | 220 | 192 |

| Tocantins | 268 | 269 | 218 | 219 | 212 | 234 | 208 | 172 | 201 | 186 |

| Northeast Region | 22,228 | 21,561 | 22,775 | 22,877 | 23,157 | 20,980 | 20,250 | 20,568 | 20,688 | 19,622 |

| Maranhão | 2637 | 2725 | 2623 | 2668 | 2760 | 2544 | 2478 | 2212 | 2163 | 2112 |

| Piauí | 1168 | 1103 | 1035 | 1102 | 1088 | 992 | 848 | 804 | 851 | 813 |

| Ceará | 3545 | 3593 | 3915 | 3855 | 3997 | 3525 | 3497 | 3838 | 3871 | 3631 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 1041 | 1080 | 1128 | 1169 | 1083 | 997 | 926 | 1020 | 971 | 910 |

| Paraíba | 1137 | 1150 | 1186 | 1219 | 1214 | 991 | 1009 | 1074 | 1067 | 1061 |

| Pernambuco | 3810 | 4043 | 4309 | 4465 | 4433 | 4067 | 4081 | 4209 | 4202 | 4128 |

| Alagoas | 1141 | 1146 | 1196 | 1183 | 1258 | 1141 | 1177 | 1204 | 1187 | 1154 |

| Sergipe | 434 | 457 | 527 | 491 | 676 | 594 | 504 | 589 | 571 | 518 |

| Bahia | 7315 | 6264 | 6856 | 6725 | 6648 | 6129 | 5730 | 5618 | 5805 | 5295 |

| Southeast Region | 32,638 | 36,269 | 35,645 | 34,742 | 33,514 | 32,820 | 32,714 | 33,776 | 32,919 | 32,724 |

| Minas Gerais | 1187 | 5029 | 5152 | 5189 | 5044 | 4691 | 4686 | 4545 | 4254 | 3867 |

| Espírito Santo | 1335 | 1333 | 1321 | 1276 | 1270 | 1201 | 1259 | 1378 | 1274 | 1298 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 13,670 | 13,584 | 13,279 | 12,943 | 12,329 | 11,582 | 11,554 | 11,848 | 11,633 | 11,310 |

| São Paulo | 16,446 | 16,323 | 15,893 | 15,334 | 14,871 | 15,346 | 15,215 | 16,005 | 15,758 | 16,249 |

| South Region | 8203 | 8913 | 9214 | 8975 | 8741 | 8308 | 8748 | 8996 | 9151 | 9095 |

| Paraná | 2635 | 2800 | 2872 | 2616 | 2676 | 2437 | 2592 | 2540 | 2406 | 2393 |

| Santa Catarina | 1352 | 1526 | 1576 | 1516 | 1485 | 1540 | 1579 | 1670 | 1650 | 1730 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 4216 | 4587 | 4766 | 4843 | 4580 | 4331 | 4577 | 4786 | 5095 | 4972 |

| Center-West Region | 3412 | 3181 | 3336 | 3096 | 3293 | 3181 | 3110 | 3185 | 3054 | 3181 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 838 | 767 | 880 | 863 | 895 | 778 | 825 | 888 | 897 | 820 |

| Mato Grosso | 1217 | 1055 | 1049 | 955 | 1119 | 1152 | 1017 | 1099 | 985 | 1186 |

| Goiás | 1012 | 1014 | 1034 | 935 | 921 | 873 | 860 | 844 | 887 | 884 |

| Distrito Federal | 345 | 345 | 373 | 343 | 358 | 378 | 408 | 354 | 285 | 291 |

| Brazil | 73,797 | 77,496 | 78,606 | 77,694 | 76,468 | 72,213 | 71,825 | 73,598 | 73,190 | 71,930 |

| Federate unit | Incidence rate |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Missing | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| North Region | 51.2 | 51.0 | 50.0 | 50.6 | 47.2 | 45.9 | 45.3 | 46.3 | 47.7 | 45.7 |

| Rondônia | 39.8 | 37.4 | 37.6 | 35.9 | 35.3 | 28.7 | 29.7 | 32.2 | 38.0 | 30.5 |

| Acre | 56.6 | 52.0 | 50.8 | 45.3 | 39.9 | 51.3 | 40.1 | 40.3 | 46.6 | 41.9 |

| Amazonas | 78.4 | 71.1 | 67.1 | 68.9 | 64.5 | 65.4 | 67.1 | 71.2 | 67.1 | 67.7 |

| Roraima | 38.8 | 41.8 | 45.1 | 50.3 | 33.2 | 30.2 | 29.1 | 32.9 | 31.3 | 28.6 |

| Pará | 47.7 | 50.8 | 51.9 | 52.9 | 49.9 | 47.0 | 46.2 | 45.6 | 48.4 | 47.5 |

| Amapá | 38.9 | 48.8 | 39.5 | 40.5 | 38.7 | 37.4 | 38.3 | 38.0 | 35.1 | 28.7 |

| Tocantins | 22.6 | 22.3 | 17.7 | 17.5 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 15.3 | 13.4 | 15.6 | 13.4 |

| Northeast Region | 46.0 | 44.1 | 46.1 | 45.9 | 45.4 | 40.7 | 38.8 | 38.7 | 38.6 | 37.0 |

| Maranhão | 46.0 | 47.0 | 44.7 | 44.9 | 45.2 | 41.1 | 39.6 | 35.1 | 34.0 | 32.1 |

| Piauí | 40.7 | 38.1 | 35.4 | 37.4 | 36.2 | 32.7 | 27.7 | 25.8 | 27.1 | 26.1 |

| Ceará | 47.0 | 46.9 | 50.5 | 49.0 | 49.4 | 42.9 | 42.0 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 43.0 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 37.0 | 37.9 | 39.1 | 40.0 | 36.1 | 32.8 | 30.0 | 32.8 | 30.9 | 28.7 |

| Paraíba | 32.8 | 32.9 | 33.7 | 34.4 | 33.8 | 27.4 | 27.6 | 28.7 | 28.3 | 28.2 |

| Pernambuco | 47.6 | 50.0 | 52.8 | 54.2 | 52.7 | 47.8 | 47.5 | 48.2 | 47.7 | 46.9 |

| Alagoas | 39.9 | 39.7 | 41.0 | 40.1 | 41.7 | 37.4 | 38.2 | 38.5 | 37.6 | 37.0 |

| Sergipe | 23.9 | 24.8 | 28.1 | 25.8 | 34.4 | 29.7 | 24.8 | 29.5 | 28.3 | 25.0 |

| Bahia | 55.4 | 47.0 | 51.0 | 49.6 | 48.1 | 43.9 | 40.7 | 38.7 | 39.7 | 37.8 |

| Southeast Region | 44.4 | 48.7 | 47.3 | 45.5 | 42.7 | 41.3 | 40.6 | 42.1 | 40.7 | 40.7 |

| Minas Gerais | 6.5 | 27.4 | 27.8 | 27.7 | 26.2 | 24.1 | 23.8 | 22.9 | 21.2 | 19.7 |

| Espírito Santo | 42.3 | 41.6 | 40.6 | 38.7 | 37.3 | 34.7 | 35.8 | 39.9 | 36.5 | 36.9 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 93.9 | 92.3 | 89.2 | 86.1 | 80.1 | 74.4 | 73.4 | 74.6 | 72.7 | 70.7 |

| São Paulo | 43.7 | 42.8 | 41.1 | 39.1 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 38.1 | 39.4 |

| South Region | 32.2 | 34.6 | 35.4 | 34.1 | 32.4 | 30.4 | 31.6 | 32.7 | 33.0 | 33.2 |

| Paraná | 27.2 | 28.6 | 29.0 | 26.1 | 26.1 | 23.5 | 24.7 | 24.0 | 22.5 | 22.9 |

| Santa Catarina | 24.8 | 27.6 | 28.1 | 26.7 | 25.3 | 25.8 | 26.1 | 27.6 | 27.0 | 27.7 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 40.9 | 44.1 | 45.3 | 45.6 | 42.2 | 39.5 | 41.3 | 44.1 | 46.7 | 46.5 |

| Center-West Region | 28.7 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 24.7 | 25.3 | 24.0 | 23.0 | 23.3 | 22.0 | 22.6 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 39.7 | 35.8 | 40.6 | 39.3 | 39.5 | 33.9 | 35.4 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 33.5 |

| Mato Grosso | 47.5 | 40.5 | 39.6 | 35.4 | 39.9 | 40.3 | 34.9 | 37.2 | 32.8 | 39.1 |

| Goiás | 19.8 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 14.4 | 15.0 | 14.7 |

| Distrito Federal | 16.4 | 16.1 | 17.0 | 15.4 | 15.3 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 13.8 | 10.9 | 11.3 |

| Brazil | 42.8 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 43.4 | 41.5 | 38.7 | 37.9 | 38.8 | 38.2 | 37.7 |

Source: Sinan-TB and Datasus.

While incidence declined 5.0% on average per year in Tocantins, there was an average increase of 1.7% annually in Sergipe. 2001 was excluded for Minas Gerais state due to migration error in databases in Sinan on that year.

These rates also fluctuated substantially over the period studied. Almost all FS had fluctuations greater than 10% from one year to another, with the exception of Amazonas, Pará, Rio Grande do Norte, Pernambuco, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul. In 2010, Amazonas, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina and Distrito Federal showed opposite trends from the remaining states.

In 2010, the highest incidence rates occurred in Rio de Janeiro (70.7), Amazonas (67.7), Pará (47.5), Pernambuco (46.9) and Rio Grande do Sul (46.5) states. In that same year, the difference between the highest and the lowest rate registered in Rio de Janeiro (70.7 per 100,000 inhabitants) and Distrito Federal (11 per 100,000 inhabitants) was higher than six times (Table 2).

As can be seen in Table 3, new cases represented 82.7% (71,930) of all reported cases in 2010. That figure was 84.6% (73,797) in 2001. Compared to 2001, the observed values in 2010 decreased in almost all FS. In 2010, the proportion of new cases among all cases notified ranged from 89.8% (1624) in São Paulo to 76.2% (1061) in Paraíba.

Table 3.

Tuberculosis cases profile according to sex, age, race, education, input in the information system and institutionalization status (Sinan-TB) – Brazil, 2001–2010.

| TB cases profile | 2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Input in information system | ||||||||||

| New case | 73,797 | 84.6 | 77,496 | 83.5 | 78,606 | 83.8 | 77,694 | 83.6 | 76,468 | 83.8 |

| Retreatment | 11,661 | 13.4 | 11,930 | 12.8 | 11,100 | 11.8 | 10,761 | 11.6 | 10,116 | 11.1 |

| Transfer from another unit | 1579 | 1.8 | 3160 | 3.4 | 3708 | 4.0 | 4191 | 4.5 | 4488 | 4.9 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 47,133 | 63.9 | 49,545 | 63.9 | 50,235 | 63.9 | 49,947 | 64.3 | 49,369 | 64.6 |

| Female | 26,584 | 36.0 | 27,877 | 36.0 | 28,361 | 36.1 | 27,735 | 35.7 | 27,067 | 35.4 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 1–4 years old | 1362 | 1.8 | 1345 | 1.7 | 1334 | 1.7 | 1217 | 1.6 | 1080 | 1.4 |

| 5–14 years old | 2005 | 2.7 | 2113 | 2.7 | 2035 | 2.6 | 1931 | 2.5 | 1965 | 2.6 |

| 15–34 years old | 30,460 | 41.3 | 31,277 | 40.4 | 31,816 | 40.5 | 31,560 | 40.7 | 30,972 | 40.5 |

| 35–64 years old | 33,558 | 45.5 | 35,792 | 46.3 | 36,373 | 46.3 | 36,058 | 46.5 | 35,598 | 46.6 |

| 65 and plus | 6306 | 8.6 | 6856 | 8.9 | 6937 | 8.8 | 6841 | 8.8 | 6790 | 8.9 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Illiterate | 8207 | 11.1 | 8886 | 11.5 | 8344 | 10.6 | 7818 | 10.1 | 7547 | 9.9 |

| Up to 8 years | 30,023 | 40.7 | 32,230 | 41.6 | 34,471 | 43.9 | 34,541 | 44.5 | 33,814 | 44.2 |

| More than 8 years | 11,013 | 14.9 | 14,570 | 18.8 | 16,792 | 21.4 | 18,052 | 23.2 | 17,895 | 23.4 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Missing | 65,414 | 88.6 | 49,404 | 63.8 | 29,477 | 37.5 | 23,781 | 30.6 | 22,472 | 29.4 |

| White | 3391 | 4.6 | 12,266 | 15.8 | 19,903 | 25.3 | 21,173 | 27.3 | 20,347 | 26.6 |

| Black | 863 | 1.2 | 4281 | 5.5 | 7542 | 9.6 | 8381 | 10.8 | 8038 | 10.5 |

| Yellow | 96 | 0.1 | 428 | 0.6 | 796 | 1.0 | 855 | 1.1 | 682 | 0.9 |

| Brown | 3715 | 5.0 | 10,532 | 13.6 | 20,135 | 25.6 | 22,836 | 29.4 | 24,318 | 31.8 |

| Indian | 318 | 0.4 | 585 | 0.8 | 753 | 1.0 | 668 | 0.9 | 610 | 0.8 |

| Institutionalization | ||||||||||

| Missing | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not institutionalized | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jail | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Institutionalized but not in jail | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TB cases profile | 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Input in information system | ||||||||||

| New case | 72,213 | 83.6 | 71,825 | 83.5 | 73,598 | 83.7 | 73,190 | 83.7 | 71,930 | 82.7 |

| Retreatment | 9884 | 11.4 | 9903 | 11.5 | 10,127 | 11.5 | 10,020 | 11.5 | 10,405 | 12.0 |

| Transfer from another unit | 4128 | 4.8 | 4291 | 5.0 | 4173 | 4.7 | 4167 | 4.8 | 4625 | 5.3 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 46,761 | 64.8 | 46,930 | 65.3 | 48,271 | 65.7 | 48,056 | 66.1 | 47,546 | 64.8 |

| Female | 25,449 | 35.2 | 24,893 | 34.7 | 25,315 | 34.3 | 25,131 | 33.9 | 24,383 | 35.2 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 1–4 years old | 1002 | 1.4 | 1034 | 1.4 | 965 | 1.3 | 1015 | 1.4 | 907 | 1.3 |

| 5–14 years old | 1708 | 2.4 | 1773 | 2.5 | 1806 | 2.5 | 1752 | 2.4 | 1536 | 2.1 |

| 15–34 years old | 29,045 | 40.3 | 28,903 | 40,3 | 29,872 | 40.6 | 29,895 | 40.9 | 29,173 | 40.6 |

| 35–64 years old | 33,778 | 46.8 | 33,553 | 46.8 | 34,408 | 46.8 | 33,997 | 46.5 | 33,654 | 46.9 |

| 65 and plus | 6595 | 9.1 | 6443 | 9.0 | 6447 | 8.8 | 6434 | 8.8 | 6545 | 9.1 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Illiterate | 5872 | 8.1 | 2985 | 4.2 | 3540 | 4.8 | 3584 | 4.9 | 3478 | 4.8 |

| Up to 8 years | 26,483 | 36.7 | 31,443 | 43.8 | 28,814 | 39.2 | 2789 | 38 | 26,322 | 36.6 |

| More than 8 years | 13,653 | 18.9 | 9651 | 13.4 | 11,944 | 16.2 | 12,841 | 17.5 | 12,757 | 17.7 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Missing | 17,660 | 24.5 | 13,361 | 18.6 | 11,649 | 15.8 | 7769 | 10.6 | 6732 | 9.4 |

| White | 20,532 | 28.4 | 22,567 | 31.4 | 24,150 | 32.8 | 25,346 | 34.6 | 25,231 | 35.1 |

| Black | 8210 | 11.4 | 8462 | 11.8 | 8948 | 12.2 | 9420 | 12.9 | 9176 | 12.8 |

| Yellow | 767 | 1.1 | 820 | 1.1 | 776 | 1.1 | 746 | 1.0 | 646 | 0.9 |

| Brown | 24,392 | 33.8 | 25,785 | 35.9 | 27,283 | 37.1 | 29,093 | 39.7 | 29,366 | 40.8 |

| Indian | 622 | 0.9 | 830 | 1.2 | 792 | 1.1 | 816 | 1.1 | 779 | 1.1 |

| Institutionalization | ||||||||||

| Missing | – | – | 23,870 | 33.2 | 17,292 | 23.5 | 3959 | 5.4 | 3565 | 5.0 |

| Not institutionalized | – | – | 42,924 | 59.8 | 50,571 | 68.7 | 62,533 | 85.4 | 61,664 | 85.7 |

| Jail | – | – | 2726 | 3.8 | 3445 | 4.7 | 4407 | 6.0 | 4643 | 6.5 |

| Institutionalized but not in jail | – | – | 2305 | 3.2 | 2290 | 3.1 | 2291 | 3.1 | 2058 | 2.9 |

Source: Sinan-TB.

In 2010, ten Brazilian FS concentrated more than 80% (57,806) of new TB cases in the country, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Rio Grande do Sul, Pernambuco, Minas Gerais, Ceará, Pará, Amazonas and Paraná. Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo themselves were responsible for 38.3% (27,559) of all new cases in the country in that same year.

Regarding demographic variables, it is observed that TB affects all population groups with predominance in males on working age. Men accounted for 63.9% (47,133) of all new cases in 2001. This proportion gradually increased until reached 66.1% (48,056) in 2009 and dropped again to 64.8% (47,546) in 2010. Tow age groups, 15–34 and 35–64 years old, concentrated more than 85% of new TB cases in the country in all the years studied.

The high number of missing records in variable “race/color” until 2006 made difficult to analyze this variable in the early years of the study. For this reason this variable was described from 2007 on. In 2010 when color was registered on more than 90% of cases, 53.6% (38,542) of new cases were brown or black and 35.1% (25,231) were white.

Regarding education, in 2001 about half the cases, 51.8% (38,230), had studied less than 8 years. Throughout the period the proportion of new cases illiterate and up to 8 years of study decreased on average 6.9% and 0.7% respectively between the years studied, while the category over 8 years of study showed an increase of 3.4% annually on average. It should be considered, however, the improvement in education among the whole Brazilian population in this period.

Table 3 shows that the proportion of new cases institutionalized in prisons increased from 3.8% (2726) in 2007 to 6.5% (4643) in 2010, an annual increase of 19.7% on average in the period.

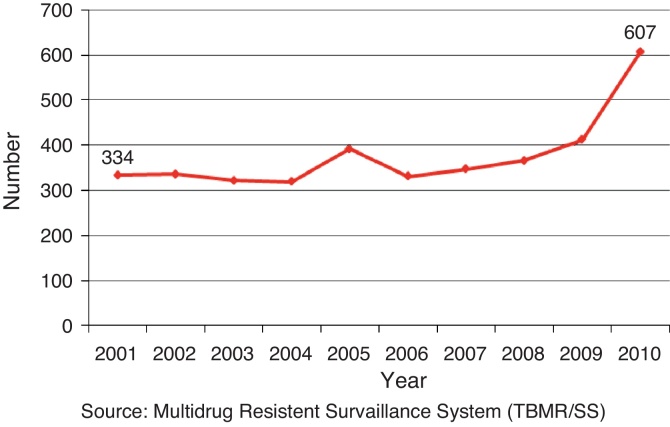

The number of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) cases in 2010 was 607. This figure was 334 in 2001. This represents an annual increase of 8.1% on average in the number of MDR-TB cases in Brazil in the 10 years studied. This increase was particularly high between 2004–2005 and 2009–2010, with 22.6% and 47.3% increase from one year to another, respectively (Fig. 2). It is important to consider that in this last period NTP began to prioritize culture and sensitivity testing for all retreatment cases and for the most vulnerable populations.

Fig. 2.

Number of multidrug resistant tuberculosis cases – Brazil, 2001–2010. Source: Multidrug Resistant Surveillance System (TBMR/SS).

The proportion of new TB cases HIV positive was 9.9% (7096) in 2010. Compared to 2001, which recorded 7.5% (5508) HIV-positive cases among all TB cases, there was an average annual increase of 3.2% in coinfection during the period studied (Table 4), reflecting the increase on HIV testing in recent years.

Table 4.

Diagnosis and treatment variables analysis of new cases (Sinan-TB) – Brazil, 2001–2010.

| New cases | 2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Pulmonary | 63,336 | 85.8 | 66,256 | 85.5 | 67,209 | 86 | 66,423 | 85.5 | 65,684 | 85.9 |

| Extrapulmonary | 10,461 | 14.2 | 11,240 | 14.5 | 11,397 | 14 | 11,270 | 14.5 | 10,784 | 14.1 |

| Sputum smear performed | 52,245 | 82.5 | 54,705 | 82.6 | 55,732 | 83 | 55,129 | 83.0 | 55,490 | 84.5 |

| Bacilliferous | 39,460 | 62.3 | 41,416 | 62.5 | 42,044 | 63 | 41,471 | 62.4 | 41,801 | 63.6 |

| Tested for HIV | 19,034 | 25.8 | 21,967 | 28.3 | 24,175 | 31 | 25,633 | 33.0 | 28,274 | 37.0 |

| HIV positive | 5508 | 7.5 | 5941 | 7.7 | 6066 | 8 | 5830 | 7.5 | 5806 | 7.6 |

| Investigated contacts | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cure | 49,954 | 67.7 | 52,688 | 68.0 | 55,137 | 70 | 54,885 | 70.6 | 55,579 | 72.7 |

| Default | 8137 | 11.0 | 7649 | 9.9 | 7453 | 9 | 7182 | 9.2 | 6881 | 9.0 |

| Transfer from another unit | 5003 | 6.8 | 5599 | 7.2 | 6237 | 8 | 5981 | 7.7 | 5769 | 7.5 |

| Death | 58 | 0.1 | 54 | 0.1 | 83 | 0 | 95 | 0.1 | 273 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 6274 | 8.5 | 6670 | 8.6 | 4705 | 6 | 4689 | 6.0 | 3069 | 4.0 |

| MDR TB | 27 | 0.0 | 62 | 0.1 | 55 | 0 | 81 | 0.1 | 76 | 0.1 |

| Cases under DOTS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| New cases | 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Pulmonary | 62,006 | 85.9 | 61,529 | 85.7 | 62,994 | 85.6 | 62,707 | 85.7 | 61,784 | 85.9 |

| Extrapulmonary | 10,201 | 14.1 | 10,290 | 14.3 | 10,588 | 14.4 | 10,464 | 14.3 | 10,128 | 14.1 |

| Sputum smear performed | 52,691 | 85.0 | 52,753 | 85.7 | 54,116 | 85.9 | 53,866 | 85.9 | 53,440 | 86.5 |

| Bacilliferous | 40,442 | 65.2 | 40,341 | 65.6 | 41,276 | 65.5 | 40,667 | 64.9 | 40,820 | 66.1 |

| Tested for HIV | 29,646 | 41.1 | 33,542 | 46.7 | 37,346 | 50.7 | 40,127 | 54.8 | 42,056 | 58.5 |

| HIV positive | 5701 | 7.9 | 6415 | 8.9 | 6648 | 9.0 | 6815 | 9.3 | 7096 | 9.9 |

| Investigated contacts | – | – | 114,218 | 57.6 | 127,205 | 56.8 | 139,741 | 61.7 | 130,948 | 57.9 |

| Cure | 52,092 | 72.1 | 51,853 | 72.2 | 53,075 | 72.1 | 51,984 | 71.0 | 44,527 | 61.9 |

| Default | 6548 | 9.1 | 6799 | 9.5 | 7130 | 9.7 | 7324 | 10.0 | 5888 | 8.2 |

| Transfer from another unit | 4843 | 6.7 | 4638 | 6.5 | 4962 | 6.7 | 5343 | 7.3 | 5741 | 8.0 |

| Death | 1336 | 1.9 | 2543 | 3.5 | 2397 | 3.3 | 2309 | 3.2 | 2196 | 3.1 |

| Missing | 3353 | 4.6 | 2928 | 4.1 | 3075 | 4.2 | 2971 | 4.1 | 10,643 | 14.8 |

| MDR TB | 76 | 0.1 | 119 | 0.2 | 99 | 0.1 | 163 | 0.2 | 108 | 0.2 |

| Cases under DOTS | – | – | 28,744 | 33.4 | 31,135 | 35.4 | 32,716 | 37.4 | 36,736 | 42.2 |

Source: Sinan-TB.

New pulmonary cases represented approximately 85% of the total cases reported in 2001 and these values remained almost constant until 2010 (Table 4).

Treatment and TCP performance

In 2001, 82.5% (52,245) of new pulmonary cases underwent microscopy sputum smear. This percentage has increased gradually until reached 86.5% (53,440) in 2010. New smear-positive cases accounted for 62.3% (39,460) of all new pulmonary cases in 2001 and there was a slight increase in this figure over the period, reaching a value of 66.1% (40,820) in 2010 (Table 4).

With an inverse behavior from cure rate, the proportion of default decreased from 11.0% (8137) in 2001 to 9.0% (6881) in 2005. Then it remained almost constant until 2009, recording 10.0% (7324) that year. In 2010, default rate was 8.2% (5888), although outcome had 14.8% (10,643) of missing data in that year.

However, this trend was not homogeneous between federal states. While default decreased on average 8.8% annually in Distrito Federal, there was an average annual increase in treatment default of 14.0% in Roraima. In 2010, default rate ranged between 2.1% (6) in Distrito Federal and 10.6% (527) in Rio Grande do Sul. Among Brazilian states, Distrito Federal, Tocantins, Piauí and Acre, showed less than 5% of default in 2009. That same year, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Pernambuco, Rondônia, Rio Grande do Sul, Maranhão and Rio de Janeiro showed default rates greater than 10%.

The proportion of treatment site transfers increased 2.1% annually on average between 2001 and 2010. In the years studied, São Paulo registered an average annual decrease of 12.4% and Acre an average annual increase of 59.4%. The proportion of treatment site transfers ranged from 0.9% (149) in São Paulo and 25.5% (49) in Amapá in 2010 (Table 5).

Table 5.

New cases outcome (Sinan-TB) – Brazil and state of residence, 2001–2010.

| Federate unit | 2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | |

| Missing | 64.6 | 18.7 | 10.6 | 69.1 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 74.2 | 10.4 | 8.6 | 73.1 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 70.9 | 12.2 | 7.8 |

| Rondônia | 72.5 | 12.5 | 9.1 | 77.2 | 10.4 | 7.3 | 69.9 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 67.5 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 73.2 | 7.8 | 13.1 |

| Acre | 83.7 | 11.4 | 0.9 | 76.7 | 10.5 | 6.6 | 70.5 | 14.4 | 9.8 | 77.7 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 80.1 | 8.2 | 6.4 |

| Amazonas | 80.2 | 10.6 | 1.2 | 79.5 | 10.2 | 3.9 | 75.4 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 74.8 | 10.3 | 7.8 | 69.9 | 11.6 | 5.6 |

| Roraima | 82.4 | 4.6 | 6.9 | 81.4 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 83.2 | 2.5 | 8.1 | 85.4 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 83.1 | 3.8 | 6.2 |

| Para | 71.8 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 73.6 | 11.4 | 9.9 | 70.8 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 72.8 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 73.0 | 10.2 | 9.4 |

| Amapá | 64.9 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 61.9 | 15.1 | 10.3 | 63.5 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 65.6 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 60.4 | 10.0 | 13.5 |

| Tocantins | 69.4 | 8.6 | 14.2 | 73.6 | 11.2 | 10.8 | 67.4 | 8.7 | 20.6 | 74.9 | 6.8 | 15.5 | 72.2 | 5.7 | 16.5 |

| Maranhão | 70.4 | 12.3 | 10.6 | 71.7 | 12.3 | 9.9 | 68.3 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 68.3 | 10.8 | 14.6 | 71.4 | 6.7 | 15.6 |

| Piauí | 72.7 | 5.0 | 17.2 | 68.3 | 3.7 | 22.7 | 75.3 | 4.1 | 13.8 | 64.9 | 3.8 | 24.6 | 68.6 | 4.3 | 19.9 |

| Ceara | 73.3 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 61.8 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 72.0 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 72.9 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 74.6 | 7.7 | 6.6 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 77.7 | 11.5 | 4.9 | 78.0 | 11.1 | 3.9 | 69.4 | 9.2 | 15.6 | 68.3 | 9.8 | 17.0 | 67.9 | 9.2 | 18.3 |

| Paraíba | 72.6 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 71.1 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 75.3 | 7.0 | 12.9 | 68.4 | 8.2 | 16.2 | 73.1 | 8.1 | 13.4 |

| Pernambuco | 64.1 | 15.4 | 8.0 | 65.3 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 64.4 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 67.1 | 10.4 | 12.5 | 67.4 | 10.4 | 12.4 |

| Alagoas | 76.2 | 11.7 | 6.3 | 71.9 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 72.2 | 9.6 | 12.3 | 75.1 | 10.7 | 7.7 | 78.5 | 9.4 | 4.9 |

| Sergipe | 81.6 | 10.1 | 3.7 | 83.8 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 82.5 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 78.6 | 10.6 | 5.5 | 70.9 | 6.5 | 14.8 |

| Bahia | 63.5 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 66.1 | 8.2 | 14.1 | 67.1 | 7.3 | 14.9 | 71.4 | 7.6 | 10.2 | 72.1 | 6.9 | 10.3 |

| Minas Gerais | 67.3 | 16.2 | 5.2 | 73.8 | 10.5 | 5.2 | 72.5 | 10.5 | 5.1 | 71.0 | 9.8 | 7.3 | 73.7 | 8.9 | 6.5 |

| Espírito Santo | 74.5 | 6.6 | 11.2 | 79.7 | 4.8 | 9.8 | 79.4 | 4.3 | 8.6 | 79.4 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 83.4 | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 51.8 | 11.9 | 4.8 | 49.5 | 10.2 | 4.3 | 57.7 | 10.5 | 5.3 | 57.1 | 11.0 | 4.8 | 66.1 | 11.2 | 5.4 |

| São Paulo | 72.5 | 12.2 | 5.3 | 73.7 | 10.9 | 4.4 | 76.8 | 9.9 | 3.4 | 78.8 | 9.0 | 2.9 | 77.9 | 9.6 | 2.8 |

| Paraná | 73.9 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 75.7 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 73.9 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 70.7 | 8.1 | 9.8 | 75.5 | 6.6 | 7.7 |

| Santa Catarina | 71.4 | 10.4 | 4.4 | 74.6 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 75.1 | 8.7 | 6.9 | 76.8 | 9.7 | 5.6 | 77.3 | 7.1 | 7.3 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 69.7 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 70.7 | 9.3 | 7.5 | 71.8 | 9.8 | 7.6 | 72.6 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 71.4 | 8.8 | 8.4 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 75.5 | 11.5 | 6.6 | 70.4 | 11.5 | 9.0 | 74.1 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 71.3 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 75.4 | 6.1 | 6.8 |

| Mato Grosso | 80.0 | 8.8 | 5.8 | 76.8 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 77.6 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 76.3 | 10.3 | 7.6 | 77.2 | 8.4 | 7.1 |

| Goiás | 71.1 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 74.2 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 69.3 | 10.3 | 10.8 | 65.5 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 68.9 | 9.2 | 12.1 |

| Distrito Federal | 86.4 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 85.2 | 6.1 | 1.7 | 84.7 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 86.0 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 83.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| Brazil | 67.7 | 11.0 | 6.8 | 68.0 | 9.9 | 7.2 | 70.1 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 70.6 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 72.7 | 9.0 | 7.5 |

| Federate unit | 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | Cure | Default | Transfer | |

| Missing | 48.4 | 9.7 | 16.1 | 50.0 | 12.0 | 26.0 | 37.3 | 8.5 | 28.8 | 29.8 | 12.3 | 33.3 | 41.1 | 7.1 | 28.6 |

| Rondônia | 71.9 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 73.6 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 73.8 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 67.4 | 10.7 | 16.6 | 60.6 | 8.6 | 13.0 |

| Acre | 79.0 | 2.8 | 7.4 | 86.9 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 85.8 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 90.4 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 82.1 | 6.5 | 1.6 |

| Amazonas | 72.9 | 10.5 | 7.2 | 66.6 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 68.0 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 72.7 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 68.6 | 9.1 | 8.1 |

| Roraima | 67.2 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 88.4 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 79.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 82.6 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 78.3 | 4.7 | 6.2 |

| Para | 71.6 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 73.1 | 11.8 | 7.9 | 71.3 | 11.9 | 8.3 | 71.3 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 65.4 | 7.7 | 11.2 |

| Amapá | 56.5 | 16.1 | 11.7 | 68.9 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 63.9 | 11.2 | 17.2 | 65.0 | 10.0 | 19.1 | 47.9 | 9.9 | 25.5 |

| Tocantins | 76.1 | 1.3 | 16.2 | 74.5 | 4.3 | 11.5 | 75.0 | 4.7 | 10.5 | 72.1 | 4.0 | 11.9 | 58.1 | 2.2 | 15.1 |

| Maranhão | 70.1 | 7.4 | 13.2 | 72.2 | 6.8 | 14.2 | 73.7 | 8.6 | 10.8 | 70.8 | 11.4 | 10.0 | 61.9 | 9.4 | 10.1 |

| Piauí | 67.7 | 3.8 | 19.0 | 69.2 | 4.1 | 17.5 | 66.3 | 4.1 | 20.0 | 61.1 | 3.1 | 16.0 | 51.8 | 3.6 | 14.9 |

| Ceara | 76.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 78.5 | 7.7 | 6.6 | 76.6 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 72.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 59.1 | 7.4 | 8.4 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 67.4 | 14.3 | 12.3 | 71.9 | 8.9 | 11.0 | 71.4 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 70.1 | 9.2 | 10.9 | 52.2 | 5.3 | 13.5 |

| Paraíba | 79.5 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 71.7 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 63.8 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 63.0 | 8.0 | 17.7 | 49.1 | 6.6 | 23.2 |

| Pernambuco | 68.9 | 8.1 | 12.2 | 68.8 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 65.2 | 11.3 | 11.6 | 60.4 | 10.4 | 12.9 | 47.8 | 8.3 | 12.9 |

| Alagoas | 78.9 | 8.9 | 4.1 | 77.2 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 74.1 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 68.5 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 57.0 | 8.6 | 13.2 |

| Sergipe | 71.9 | 9.8 | 12.3 | 77.8 | 13.3 | 3.6 | 74.9 | 14.1 | 3.9 | 74.3 | 9.8 | 5.6 | 75.7 | 7.7 | 5.0 |

| Bahia | 66.9 | 6.2 | 8.9 | 70.6 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 71.6 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 68.6 | 6.6 | 11.9 | 55.7 | 5.3 | 13.8 |

| Minas Gerais | 72.8 | 8.8 | 7.5 | 74.2 | 9.0 | 5.8 | 74.8 | 8.8 | 5.8 | 73.6 | 10.1 | 5.5 | 64.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| Espírito Santo | 77.7 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 80.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 80.6 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 78.6 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 71.4 | 7.0 | 7.2 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 67.8 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 64.7 | 12.6 | 5.0 | 65.4 | 11.6 | 6.3 | 67.2 | 14.0 | 6.2 | 48.7 | 9.2 | 6.1 |

| São Paulo | 76.1 | 10.5 | 0.9 | 75.9 | 10.5 | 1.2 | 77.8 | 10.3 | 1.1 | 77.4 | 10.3 | 1.3 | 76.1 | 9.3 | 0.9 |

| Paraná | 73.5 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 73.2 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 73.5 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 71.9 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 65.9 | 6.6 | 8.1 |

| Santa Catarina | 76.7 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 75.2 | 6.8 | 8.9 | 73.3 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 75.0 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 67.1 | 5.7 | 12.9 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 70.9 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 70.3 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 68.1 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 66.2 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 59.3 | 10.6 | 11.7 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 77.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 74.3 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 73.5 | 7.0 | 5.1 | 69.0 | 8.4 | 5.0 | 57.9 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| Mato Grosso | 75.7 | 6.6 | 8.3 | 78.3 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 76.9 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 72.9 | 7.6 | 9.9 | 54.1 | 7.1 | 12.3 |

| Goiás | 65.2 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 70.3 | 8.6 | 11.2 | 73.0 | 7.9 | 9.4 | 70.9 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 57.6 | 6.0 | 10.2 |

| Distrito Federal | 81.7 | 3.2 | 6.6 | 85.5 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 82.2 | 3.7 | 9.9 | 86.3 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 76.3 | 2.1 | 8.6 |

| Brazil | 72.1 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 72.2 | 9.5 | 6.5 | 72.1 | 9.7 | 6.7 | 71.0 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 61.9 | 8.2 | 8.0 |

Source: Sinan-TB.

13.4% (11,661) of all cases reported in 2001 were retreatment. Half of those were relapse and half readmission after default, representing 6.8% (5957) and 6.5% (5704) respectively. These values remained almost constant over the period, and in 2010 the proportion of retreatment was 12% (10,405).

Sputum culture in retreatment cases showed an average annual increase of 10.4% during the study period. The percentage of sputum culture tests conducted among retreatment cases in 2010 was 30.1% (2932) and in 2001 was 12.5% (1353) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Diagnosis and treatment variables analysis of retreatment cases (Sinan-TB) – Brazil, 2001–2010.

| Retreatment | 2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Relapse | 5957 | 6.8 | 6293 | 6.8 | 5863 | 6 | 5626 | 6.1 | 5325 | 5.8 |

| Readmission after default | 5704 | 6.5 | 5637 | 6.1 | 5237 | 6 | 5135 | 5.5 | 4791 | 5.2 |

| Culture performed | 1353 | 12.5 | 1412 | 12.8 | 1457 | 14.2 | 1497 | 15.0 | 1582 | 16.9 |

| Cure | 5957 | 51.1 | 6016 | 50.4 | 5819 | 52 | 5636 | 52.4 | 5512 | 54.5 |

| Default | 2523 | 21.6 | 2495 | 20.9 | 2410 | 22 | 2313 | 21.5 | 2159 | 21.3 |

| Death | 11 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.1 | 12 | 0 | 27 | 0.3 | 72 | 0.7 |

| Transfer from another unit | 944 | 8.1 | 1001 | 8.4 | 1100 | 10 | 942 | 8.8 | 904 | 8.9 |

| Missing | 1334 | 11.4 | 1501 | 12.6 | 849 | 8 | 1001 | 9.3 | 661 | 6.5 |

| MDR TB | 36 | 0.3 | 55 | 0.5 | 55 | 0 | 66 | 0.6 | 77 | 0.8 |

| Retreatment | 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Relapse | 5488 | 6.4 | 5202 | 6.0 | 5181 | 5.9 | 5037 | 5.8 | 5251 | 6.0 |

| Readmission after default | 4396 | 5.1 | 4701 | 5.5 | 4946 | 5.6 | 4983 | 5.7 | 5154 | 5.9 |

| Culture performed | 1846 | 20.1 | 2104 | 22.9 | 2300 | 24.5 | 2383 | 25.5 | 2932 | 30.1 |

| Cure | 5436 | 55.0 | 5186 | 52.4 | 5202 | 51.4 | 4799 | 47.9 | 4161 | 40.0 |

| Default | 2172 | 22.0 | 2335 | 23.6 | 2497 | 24.7 | 2561 | 25.6 | 2158 | 20.7 |

| Death | 277 | 2.8 | 451 | 4.6 | 432 | 4.3 | 455 | 4.5 | 355 | 3.4 |

| Transfer from another unit | 781 | 7.9 | 780 | 7.9 | 863 | 8.5 | 985 | 9.8 | 1156 | 11.1 |

| Missing | 580 | 5.9 | 622 | 6.3 | 635 | 6.3 | 653 | 6.5 | 2030 | 19.5 |

| MDR TB | 90 | 0.9 | 132 | 1.3 | 121 | 1.2 | 132 | 1.3 | 164 | 1.6 |

Source: Sinan-TB.

Regarding retreatment cases outcome, in 2001, 51.1% (5957) cured, 21.6% (2523) were default, 8.1% (944) were transferred to another treatment site, and 0.3% (36) developed MDR-TB. These values remained almost constant over the period, with the exception of MDR-TB who presented an average annual increase of 21.3%. The proportion of missing data on closure got down 4.6% on average between 2001 and 2009, falling from 11.4% (1334) in 2001 to 6.5% (653) in 2009. In 2010, the proportion of missing data regarding closure was 19.5% (2030).

As can be seen in Table 4, the proportion of cases contained in the national database submitted to DOTS increased from 33.4% (28,744) in 2007 to 42.2% (36,763) in 2010. This represents an annual increase in the proportion of cases under DOTS of 8.2% on average.

In the 10 years studied, there were 180,363 hospital admissions duo to TB in Brazil, and this represented a 206 million dollars in hospital charges. In 2010, 16,153 hospital admissions were recorded in Brazil duo to all forms of TB, compared to 18,523 in 2001, representing an annual decrease of 1.0% on average. However, this trend was not uniform throughout the period, nor between FS. While São Paulo experienced an average annual decrease of 13.0% in TB hospitalizations during the study period, with 2020 admissions for TB in 2010, Sergipe had an average annual increase of 169.6%, with 43 admissions for TB in 2010. Santa Catarina, Paraná and Goiás also showed an average increase of more than 20% in hospital admissions for TB during the study period.

In 2001, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro states alone concentrated 54.1% (10,027) of all admissions in the country for TB. In 2010, these states accounted for 27.5% (4200) of TB admissions. This decrease was mainly a decrease in the number of hospitalizations in the state of São Paulo. Paraná, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Pernambuco and Rio Grande do Sul in 2010 contributed over 5% each in the total of hospital admissions for TB in the country.

The average cost of hospital admissions duo to TB also varied over the years studied and between federal states. In 2001, R$ 751.14 was the average cost for this kind of hospitalization in the country, and in 2010 that figure raised up to R$ 1478.93. There was an average annual increase of 8.2% on the average cost of hospitalization for TB in Brazil in the period. Sergipe, Goiás and Amazonas had an average annual increase of 25.3%, 21.9% and 19.3%, respectively, on the average cost of hospitalization due to TB (Table 7).

Table 7.

Hospital admissions duo to tuberculosis (SIH-SUS) – Brazil and state of residence, 2001–2010.

| Federate unit | 2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | |

| Rondônia | 169 | 0.9 | 455.3 | 120 | 0.6 | 437.3 | 175 | 0.8 | 448.6 | 158 | 0.8 | 489.6 | 132 | 0.7 | 584.7 |

| Acre | 104 | 0.6 | 478.3 | 139 | 0.7 | 598.4 | 136 | 0.6 | 729.4 | 107 | 0.5 | 774.4 | 106 | 0.6 | 679.6 |

| Amazonas | 291 | 1.6 | 504.1 | 277 | 1.4 | 524.8 | 661 | 3.2 | 733.3 | 884 | 4.3 | 866.8 | 874 | 4.7 | 1014.2 |

| Roraima | 60 | 0.3 | 465.4 | 55 | 0.3 | 528.7 | 54 | 0.3 | 555.3 | 42 | 0.2 | 663.4 | 40 | 0.2 | 634.4 |

| Pará | 640 | 3.5 | 501.2 | 591 | 3.0 | 518.5 | 595 | 2.8 | 540.0 | 627 | 3.1 | 646.7 | 463 | 2.5 | 693.3 |

| Amapá | 91 | 0.5 | 458.7 | 87 | 0.4 | 467.0 | 47 | 0.2 | 541.1 | 59 | 0.3 | 524.7 | 57 | 0.3 | 630.5 |

| Tocantins | 48 | 0.3 | 431.0 | 41 | 0.2 | 529.5 | 45 | 0.2 | 641.2 | 85 | 0.4 | 549.2 | 80 | 0.4 | 606.2 |

| Maranhão | 397 | 2.1 | 467.1 | 339 | 1.7 | 554.0 | 330 | 1.6 | 549.7 | 318 | 1.6 | 654.5 | 316 | 1.7 | 691.3 |

| Piauí | 151 | 0.8 | 431.1 | 271 | 1.4 | 561.0 | 254 | 1.2 | 549.9 | 175 | 0.9 | 577.8 | 236 | 1.3 | 649.7 |

| Ceará | 367 | 2.0 | 645.3 | 714 | 3.6 | 867.2 | 555 | 2.6 | 945.8 | 487 | 2.4 | 838.8 | 498 | 2.7 | 759.4 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 236 | 1.3 | 570.1 | 287 | 1.5 | 653.8 | 281 | 1.3 | 623.1 | 302 | 1.5 | 697.8 | 238 | 1.3 | 903.0 |

| Paraíba | 414 | 2.2 | 546.3 | 492 | 2.5 | 615.0 | 555 | 2.6 | 719.0 | 526 | 2.6 | 723.9 | 525 | 2.8 | 697.3 |

| Pernambuco | 1057 | 5.7 | 717.9 | 1103 | 5.6 | 735.7 | 1235 | 5.9 | 598.6 | 1720 | 8.4 | 611.8 | 1308 | 7.1 | 976.1 |

| Alagoas | 102 | 0.6 | 464.8 | 258 | 1.3 | 570.0 | 307 | 1.5 | 639.1 | 281 | 1.4 | 846.9 | 326 | 1.8 | 898.1 |

| Sergipe | 2 | 0.0 | 400.0 | 29 | 0.1 | 902.5 | 35 | 0.2 | 1271.3 | 30 | 0.1 | 769.2 | 23 | 0.1 | 762.9 |

| Bahia | 895 | 4.8 | 590.9 | 802 | 4.1 | 702.5 | 820 | 3.9 | 643.9 | 1084 | 5.3 | 681.5 | 1364 | 7.4 | 839.4 |

| Minas Gerais | 1021 | 5.5 | 789.6 | 1481 | 7.5 | 879.7 | 1493 | 7.1 | 958.8 | 1470 | 7.2 | 1101.5 | 1459 | 7.9 | 1145.3 |

| Espírito Santo | 150 | 0.8 | 527.0 | 109 | 0.6 | 507.5 | 240 | 1.1 | 432.6 | 174 | 0.9 | 443.8 | 120 | 0.6 | 577.5 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 2491 | 13.4 | 819.4 | 2291 | 11.6 | 857.6 | 2288 | 10.9 | 839.7 | 2563 | 12.5 | 890.5 | 2279 | 12.3 | 896.8 |

| São Paulo | 7536 | 40.7 | 863.2 | 7197 | 36.4 | 880.1 | 6991 | 33.4 | 920.8 | 5780 | 28.3 | 945.0 | 5008 | 27.1 | 1005.4 |

| Paraná | 463 | 2.5 | 888.8 | 725 | 3.7 | 1101.2 | 833 | 4.0 | 1103.2 | 856 | 4.2 | 1275.4 | 654 | 3.5 | 1170.9 |

| Santa Catarina | 133 | 0.7 | 575.4 | 291 | 1.5 | 1051.0 | 276 | 1.3 | 1063.9 | 181 | 0.9 | 850.9 | 185 | 1.0 | 908.1 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 759 | 4.1 | 733.2 | 1229 | 6.2 | 903.5 | 1608 | 7.7 | 975.9 | 1492 | 7.3 | 1051.6 | 1373 | 7.4 | 1056.1 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 297 | 1.6 | 766.7 | 284 | 1.4 | 788.0 | 403 | 1.9 | 795.0 | 340 | 1.7 | 823.9 | 317 | 1.7 | 838.4 |

| Mato Grosso | 222 | 1.2 | 511.1 | 200 | 1.0 | 561.8 | 199 | 0.9 | 534.7 | 176 | 0.9 | 581.8 | 110 | 0.6 | 705.1 |

| Goiás | 221 | 1.2 | 532.1 | 221 | 1.1 | 643.9 | 321 | 1.5 | 722.2 | 308 | 1.5 | 656.7 | 282 | 1.5 | 746.6 |

| Distrito Federal | 206 | 1.1 | 535.6 | 139 | 0.7 | 568.7 | 211 | 1.0 | 544.3 | 199 | 1.0 | 566.9 | 126 | 0.7 | 623.8 |

| Brazil | 18,523 | 100.0 | 751.1 | 19,772 | 100.0 | 814.6 | 20,948 | 100.0 | 832.8 | 20,424 | 100.0 | 869.2 | 18,499 | 100.0 | 938.7 |

| Federate unit | 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | n | % | Average value | |

| Rondônia | 104 | 0.6 | 630.3 | 98 | 0.6 | 632.7 | 62 | 0.3 | 105.5 | 93 | 0.6 | 239.0 | 117 | 0.7 | 148.8 |

| Acre | 95 | 0.6 | 637.1 | 144 | 0.9 | 680.2 | 94 | 0.5 | 202.3 | 121 | 0.8 | 377.5 | 80 | 0.5 | 450.4 |

| Amazonas | 359 | 2.1 | 701.0 | 277 | 1.8 | 886.1 | 284 | 1.6 | 495.3 | 300 | 1.9 | 572.4 | 453 | 2.8 | 1437.7 |

| Roraima | 41 | 0.2 | 679.1 | 39 | 0.3 | 756.2 | 36 | 0.2 | 223.6 | 28 | 0.2 | 254.5 | 50 | 0.3 | 444.4 |

| Pará | 428 | 2.5 | 635.2 | 379 | 2.4 | 693.4 | 449 | 2.5 | 786.5 | 475 | 3.1 | 1219.2 | 399 | 2.5 | 1231.2 |

| Amapá | 47 | 0.3 | 663.4 | 24 | 0.2 | 734.2 | 68 | 0.4 | 263.1 | 52 | 0.3 | 140.4 | 44 | 0.3 | 146.9 |

| Tocantins | 114 | 0.7 | 658.4 | 102 | 0.7 | 538.4 | 111 | 0.6 | 421.0 | 91 | 0.6 | 1065.7 | 87 | 0.5 | 877.0 |

| Maranhão | 290 | 1.7 | 654.1 | 263 | 1.7 | 651.3 | 327 | 1.8 | 524.5 | 175 | 1.1 | 288.8 | 167 | 1.0 | 445.2 |

| Piauí | 150 | 0.9 | 596.2 | 156 | 1.0 | 583.7 | 142 | 0.8 | 544.9 | 127 | 0.8 | 675.7 | 142 | 0.9 | 759.0 |

| Ceará | 607 | 3.6 | 729.8 | 562 | 3.6 | 739.1 | 556 | 3.0 | 839.1 | 700 | 4.5 | 1329.0 | 708 | 4.4 | 1121.4 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 358 | 2.1 | 1039.5 | 299 | 1.9 | 1102.6 | 354 | 1.9 | 939.9 | 403 | 2.6 | 1507.6 | 428 | 2.6 | 1638.6 |

| Paraíba | 607 | 3.6 | 684.7 | 582 | 3.8 | 694.0 | 444 | 2.4 | 1279.0 | 536 | 3.5 | 1548.5 | 724 | 4.5 | 1598.3 |

| Pernambuco | 965 | 5.7 | 1006.7 | 999 | 6.5 | 1087.7 | 1648 | 9.0 | 1717.4 | 1354 | 8.8 | 1790.5 | 1470 | 9.1 | 1685.9 |

| Alagoas | 186 | 1.1 | 835.2 | 221 | 1.4 | 854.6 | 178 | 1.0 | 455.1 | 223 | 1.4 | 694.5 | 250 | 1.5 | 1168.9 |

| Sergipe | 72 | 0.4 | 1173.2 | 59 | 0.4 | 829.1 | 36 | 0.2 | 475.6 | 26 | 0.2 | 1243.3 | 43 | 0.3 | 724.4 |

| Bahia | 1255 | 7.4 | 909.3 | 1254 | 8.1 | 1084.8 | 1090 | 6.0 | 968.2 | 1161 | 7.5 | 1574.0 | 1369 | 8.5 | 1604.5 |

| Minas Gerais | 1485 | 8.8 | 1154.5 | 1203 | 7.8 | 1338.9 | 1461 | 8.0 | 1136.5 | 1384 | 9.0 | 1347.1 | 1302 | 8.1 | 1426.1 |

| Espírito Santo | 120 | 0.7 | 695.4 | 127 | 0.8 | 705.5 | 128 | 0.7 | 882.7 | 167 | 1.1 | 1114.9 | 143 | 0.9 | 1321.3 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 2166 | 12.8 | 932.6 | 2233 | 14.4 | 937.7 | 2243 | 12.3 | 776.5 | 2191 | 14.2 | 980.9 | 2180 | 13.5 | 1173.1 |

| São Paulo | 4584 | 27.1 | 973.7 | 4020 | 26.0 | 938.9 | 2715 | 14.9 | 1248.1 | 2050 | 13.3 | 1529.1 | 2020 | 12.5 | 1590.7 |

| Paraná | 633 | 3.7 | 1246.4 | 551 | 3.6 | 1328.8 | 2037 | 11.2 | 1265.5 | 961 | 6.2 | 2119.0 | 913 | 5.7 | 2150.8 |

| Santa Catarina | 252 | 1.5 | 1135.7 | 184 | 1.2 | 1170.3 | 330 | 1.8 | 1181.3 | 412 | 2.7 | 1607.9 | 422 | 2.6 | 1523.4 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 1048 | 6.2 | 1022.1 | 952 | 6.1 | 995.1 | 1907 | 10.5 | 1232.3 | 1639 | 10.6 | 1773.9 | 1805 | 11.2 | 1782.7 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 367 | 2.2 | 964.5 | 323 | 2.1 | 867.8 | 313 | 1.7 | 1460.9 | 233 | 1.5 | 1793.5 | 279 | 1.7 | 1587.1 |

| Mato Grosso | 118 | 0.7 | 653.3 | 86 | 0.6 | 697.1 | 121 | 0.7 | 931.5 | 73 | 0.5 | 885.1 | 83 | 0.5 | 1478.0 |

| Goiás | 301 | 1.8 | 877.1 | 219 | 1.4 | 684.9 | 970 | 5.3 | 594.3 | 299 | 1.9 | 1520.9 | 346 | 2.1 | 1482.7 |

| Distrito Federal | 154 | 0.9 | 812.0 | 131 | 0.8 | 634.5 | 142 | 0.8 | 345.7 | 131 | 0.9 | 571.5 | 129 | 0.8 | 280.2 |

| Brazil | 16,906 | 100.0 | 940.1 | 15,487 | 100.0 | 962.3 | 18,246 | 100.0 | 1074.7 | 15,405 | 100.0 | 1416.8 | 16,153 | 100.0 | 1478.9 |

Source: Unified Health System Hospital Information System (SIH/SUS).

Mortality

Brazil has experienced an average annual decline in TB mortality rate of 2.9% between 2001 and 2010. In 2010, TB mortality rate was 2.4 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. As the incidence rate, this trend was not uniform across states. While Paraná showed an annual decrease of 6.5% on average on mortality rate, Paraíba had an average annual increase of 10.9% in their rate.

Just as hospital admissions, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro concentrated the majority of TB deaths in the country, accounting together for 43.3% (2349) of all deaths duo to TB in the country in 2001. This proportion has decreased over the study period, falling to 37.8% (1740) in 2010 (Table 8).

Table 8.

Number of deaths and crude mortality rate (SIM) – Brazil and state of residence, 2001–2010.

| Federate unit | Number of deaths |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Rondônia | 35 | 37 | 46 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 25 | 34 | 20 | 27 |

| Acre | 26 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 27 | 23 | 28 | 16 | 16 | 15 |

| Amazonas | 117 | 106 | 102 | 88 | 104 | 107 | 96 | 113 | 133 | 110 |

| Roraima | 10 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Pará | 175 | 129 | 152 | 170 | 152 | 155 | 169 | 179 | 180 | 169 |

| Amapá | 11 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 13 |

| Tocantins | 13 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 11 | 14 | 12 |

| Maranhão | 121 | 125 | 116 | 159 | 181 | 179 | 168 | 196 | 192 | 186 |

| Piauí | 56 | 79 | 71 | 64 | 73 | 72 | 78 | 84 | 81 | 71 |

| Ceará | 256 | 232 | 191 | 214 | 232 | 264 | 253 | 269 | 276 | 239 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 67 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 52 | 42 | 70 | 71 | 53 | 63 |

| Paraíba | 53 | 86 | 113 | 79 | 142 | 109 | 67 | 75 | 80 | 86 |

| Pernambuco | 422 | 401 | 427 | 436 | 398 | 379 | 418 | 403 | 397 | 354 |

| Alagoas | 79 | 89 | 89 | 70 | 76 | 83 | 85 | 95 | 99 | 91 |

| Sergipe | 34 | 26 | 30 | 39 | 41 | 43 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 39 |

| Bahia | 429 | 470 | 418 | 412 | 375 | 440 | 428 | 434 | 406 | 377 |

| Minas Gerais | 293 | 312 | 308 | 333 | 319 | 298 | 298 | 306 | 315 | 285 |

| Espírito Santo | 68 | 64 | 71 | 70 | 51 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 70 | 61 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 1030 | 961 | 889 | 910 | 789 | 848 | 825 | 870 | 815 | 889 |

| São Paulo | 1319 | 1158 | 1120 | 1053 | 928 | 970 | 921 | 910 | 922 | 851 |

| Paraná | 212 | 192 | 203 | 191 | 169 | 176 | 141 | 152 | 122 | 118 |

| Santa Catarina | 57 | 57 | 59 | 56 | 51 | 54 | 46 | 59 | 65 | 61 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 308 | 314 | 276 | 281 | 277 | 242 | 275 | 290 | 273 | 258 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 58 | 63 | 62 | 68 | 66 | 57 | 48 | 59 | 67 | 66 |

| Mato Grosso | 94 | 95 | 70 | 76 | 86 | 80 | 87 | 78 | 82 | 98 |

| Goiás | 59 | 57 | 68 | 68 | 70 | 65 | 59 | 50 | 57 | 47 |

| Distrito Federal | 23 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 15 | 10 | 18 | 9 | 6 | 13 |

| Brazil | 5425 | 5162 | 4987 | 4981 | 4735 | 4823 | 4735 | 4881 | 4797 | 4603 |

| Federate unit | Mortality rate |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Rondônia | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Acre | 4.5 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| Amazonas | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.2 |

| Roraima | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Pará | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| Amapá | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| Tocantins | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Maranhão | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| Piauí | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| Ceará | 3.4 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Paraíba | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Pernambuco | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| Alagoas | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| Sergipe | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Bahia | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| Minas Gerais | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Espírito Santo | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| São Paulo | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Paraná | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Santa Catarina | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| Mato Grosso | 3.7 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.2 |

| Goiás | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Distrito Federal | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Brazil | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

Source: Mortality Information System (SIM).

Discussion

According to key epidemiological and operational TB indicators analysis made in this article, many advances on tuberculosis control in Brazil were achieved in the last 10 years. It is important to say that Sinan database is updated monthly for HM. For this reason, indicators analyzed in this study may have significant change in value at the time of publication.

There was an increase in the number of municipalities that diagnosed and reported TB cases in the surveillance system. This result may infer the expansion of TB control programs coverage in the country, since diagnosis and reporting are primary activities of an implemented program. However, attention should be paid to about 40% of municipalities with no known cases of the disease, pointing to the existence of silent municipalities. The state programs should be aware of municipalities with this behavior so that disease surveillance failures can be identified and corrected.

In recent years Brazil showed a significant improvement in case detection rate when compared to WHO estimates. TB control decentralization to primary care can be a facilitator to diagnosis and information access. However, it must be consider that WHO's method of calculating estimated cases has changed over the series analyzed, which may have influenced this indicator improvement.4

The incidence rate is an indicator that measures the risk of illness of a given population in a given location and time. For TB, a chronic and difficult to treat disease, control requires actions shared with sectors outside health sector, which may explain the slight drop in annual incidence. This indicator behavior tends to be different between regions and states in the country, because it is influenced by implementation stage of TB control actions in the locality. Places where control actions are more consolidated tend to have more significant reduction. Political issues influence must also be raised, since successive changes in administrations, particularly in cities, leads to discontinuation in efforts and causes changes in TB indicators. However, fluctuations more than 10% from one year to another should be investigated, since it may indicate cases underreporting and compromise disease surveillance quality.

The highest TB incidence among males and young adults is a reality worldwide.1 This profile, besides having the highest incidence, is the one with grater treatment default. Because most patients are in working age, access to diagnosis and treatment is complicated because working and health facilities opening hours usually match. To minimize this problem municipalities must create different strategies, such as alternative hours for primary care function and partnerships with patients’ workplaces.

Analysis of “race,” “education” and “closure” variables were hampered by missing fields. This problem was highlighted in several studies5, 6, 7 as a limiting factor of any epidemiological analysis. Analysis of field completeness in Sinan should be a routine activity in surveillance to ensure variables reliability.

The collecting process of information of the variable “race,” jeopardizes data reliability. In some places this variable is self-reported, while in others it is biased by health workers opinion who writes down information without patient knowledge. Even with the described limitations, black and brown colors accounted for the largest quantity of cases, as already demonstrated in literature.8 Significant increase in cases of white color should be considered when analyzing data, suggesting an increased risk of illness over the years analyzed. Although in lesser extent, only approximately 1.1% of cases, Indian race is a cause of concern due to its high risk of illness and difficult diagnosis and treatment access.3

Variable “education status” is perhaps the only variable in Sinan that can be used as proxy of patient's socioeconomic status. Although it was not this study subject, an additional concern, beyond this group higher risk of getting ill, is that people with less education also have an increased risk of unfavorable outcomes, such as treatment default and death. Local strategies of social support through food baskets distribution and offset help aim to improve treatment adherence.

Recognition that prison people are more vulnerable to TB when compared to general population was important to raise the need of direct recommendations to this population group. Incorporation of the variable “incarcerated” in Sinan in 2007 already showed concern in quantifying this problem magnitude. Global Fund TB Project implementation in Brazil, with a working component directed to prison system, supported TNP to spread this topic importance, as well as training professionals in states and municipalities. This work result can be seen in figures, since gradual increase in incarcerated reported cases in Sinan suggests the problem has been recognized and worked more systematically in recent years. However, the link between Health and Justice Sectors remains a major challenge for disease control in the country.

TB/HIV cases require special attention, since they have higher risk of unfavorable treatment outcomes.9 Increase in reported cases of coinfection seems to be related to increase on HIV testing among TB cases, which doubled over the years analyzed, although co-infection percentage did not increase in that same proportion. These data support the hypothesis that a few years ago, only one group of TB cases, perhaps the one possessing greatest risk on health workers judgment, were tested for HIV. Delay on returning test results to the health units and also on updating the surveillance system may be responsible for HIV testing figures lower than reality. The introduction of rapid HIV testing in health care system may have contributed to minimize this problem, since result comes out in minutes, allowing health workers to know almost immediately the patient's HIV status.

MDR-TB cases have higher probability of unfavorable outcomes, as well the possibility of adverse effects, beyond longer treatment when compared to sensitives.1, 10 Increase in number of MDR TB cases in the years studied appears to be associated with increase in culture testing in the same period, particularly in retreatment cases. MH recommends culture and sensitivity testing for all retreatment cases in order to identify drug resistance early, although culture testing is still very low. 30% of retreatment cases had culture done in 2010 and it has doubled when compared to 2001.

Increase on pulmonary cases that performed sputum smear on the evaluated years is a program quality indicator since as a consequence a smaller volume of cases will be treated without bacteriological confirmation. However, increase in active tuberculosis cases percentage cause concern, since they are responsible for the transmission chain maintenance and disease perpetuation. Diagnosing these cases early is an essential activity for TB control.

According to Freire,11 the risk of case contacts developing TB, in a five years follow-up study, was 2300 cases per 100,000 contacts (4.6/1000 contacts/year). This finding reinforces the recommendation that all contacts should be investigated after a case diagnosis for other patients early identification and future cases prevention. Despite the variable “contacts investigated” had been inserted in Sinan in 2007, their inclusion did not have the same effect as the inclusion of the variable “institutionalized”, since there was not a increase in contacts investigation in the 10 years analyzed. Some limiting factors such as fail in fulfilling the Record Books, fail in updating the information system with follow-up information and health workers misunderstandings about the concept of a contact investigated must be taken into consideration.

Cure and default rates are subject of major national and international targets. However, rates closest to reality may be only found in approximately 1.5 years after case diagnosis. Because treatment is long, deficiencies in following-up cases and as consequence in follow-up bulletins that update Sinan can be identified as possible causes of cases without closure maintenance. Some states are known to have, historically, rates equal or above of those recommended by WHO, but it is not a national reality. Variations between federal states can be express by health care models adopted, diagnosed cases complexity, health services organization and surveillance quality.

Treatment default is a major challenge in TB control today. Men, alcohol and drugs users, diabetics, coinfection cases, institutionalized cases and homeless people are recognized as vulnerable groups to default. For them, alternative strategies for follow-up should be performed. Aiming to contribute in reducing default and preventing MDR TB, MH changed his therapeutic regimen from three to four drugs and adopted the so-called fixed-dose combination (FDC) or “4 in 1”, where four drugs are gathered into the same pill. This event marked a milestone for disease control in the country and it is expected that in a near future results can be measured.

Several studies have demonstrated DOTS effectiveness in TB cases.12, 13 The two indicators about DOTS analyzed tended to increase over the study period, but some points should be taken into account when interpreting these figures. Until 2010, health workers responsible for TB treatment interpreted DOTS concept in several different ways. Therefore, NTP has developed a more specific rule to consider a case to be under DOTS, and published in his manual of recommendations.3 This change on DOTS concept should result in this indicator reduction over the next year making it closer to reality. In addition, in all cases DOTS is automatically filled by the system as performed, requiring upgrade if not performed. This procedure in Sinan may be overestimating these values.

Although in a small amount, the number of hospital admissions duo to TB decreased from 2001 to 2010. Hospitalizations duo TB may be associated with delay in diagnosis and irregular treatment, as well as cases that tend to develop more severe forms of the disease.14, 15 The increase in family health strategy coverage may be influencing reduction in hospitalizations, duo to expansion of access to diagnosis and treatments. Despite this national trend, some states had their hospitalizations increased. A possible explanation for Santa Catarina and Paraná states is the high number of TB/HIV coinfection cases when compared to other Brazilian states, which can cause serious complications leading to hospitalization. States that have high default rates also tend to have more hospitalizations due the disease, since these cases do not have treatment under control.

Regarding mortality from TB analysis, the country shows declining trend for over a decade, more pronounced until 2006. The cooling on the mortality drop can be explained by Ministry of Health strategy to reduce deaths due to unknown causes or poorly defined in that year. Due to this activity about 300 deaths each year have been attributed to TB after investigation. In 2011, Brazil achieved the STOP TB Partnership target to reduce mortality by 50% when compared to 1990. However, when analyzing mortality we should be alert to TB as associated cause in death, once in cases of coinfection, for example, AIDS remains the primary cause of death because criteria in causes of death classification. Underreporting deaths duo to or with TB in Sinan is a problem already explained in literature and need to be worked by states and municipalities.15, 16, 17 The implementation of deaths duo to or with TB investigation routine may help reduce this problem since done systematically and with well-defined criteria.

Further advances can be described when we analyze the last 10 years of TB control in the country. The maintenance of TB as a priority on government political agenda, as well as maintaining epidemiological and operational TB indicators in major national agreements should be highlighted. The creation of metropolitan committees for fighting against TB as spaces of link between civil society and government in 11 metropolitan areas has allowed the expansion of partnerships for control actions. In the laboratory field, the introduction of real time molecular biology test, rapid test (validation in real conditions still undergoing) can provide greater agility in diagnosis.

For many years WHO took a expectancy position regarding tuberculosis control in Brazil, given the poor results obtained and the reluctance on the country's behavior to adopt WHO's recommendations. This attitude contrasted with recognition given to National STD/AIDS (DST/AIDS-NP) and Immunization (NIP) programs as international models. Since 2003, however, with tuberculosis control prioritization and its election as one of the Ministry of Health (MoH) priorities, WHO has demonstrated its recognition regarding national efforts.

Despite significant advances, many challenges must be overcome so eliminating TB as a public health problem goal can be achieved. When assessing the past we must say that improvement in indicators cannot be explained only by tuberculosis control program efforts. We must also consider TB social causes and prioritize mitigation of factors that increase some population segments vulnerability to the disease and promote actions that facilitate diagnosis access and treatment adherence.

Partnership with social movements and interaction with other sectors, particularly with social welfare, justice and institutions that work in promoting human rights, racial equality, combating the abuse of licit drugs (such as tobacco and alcohol) and illicit (especially crack), as well as liaison with legislature, to enable projects that benefit patients with tuberculosis and their families, with social support measures and inclusion in social programs, and facilitate access to health services. These steps are essential for more consistent results to be achieved in the medium and long term.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2011. Global tuberculosis control 2011: WHO report 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; Geneva: 2008. Report 2008. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil . Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica; Brasília: 2011. Manual de recomendações para o controle da tuberculose no Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . 2010. Taxa de Incidência e Mortalidade dos países. Available at: http://www.who.int/whosis/database/core/core_select_process.cfm# (cited 25 July) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreira C.M., Maciel E.L. Completeness of tuberculosis control program records in the case registry database of the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil: analysis of the 2001–2005. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:225–229. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malhao T.A., Oliveira G.P., Codenotti S.B., Moherdaui F. Avaliação da completitude do sistema de informação de agravos de notificação da tuberculose, Brasil (2001–2006) Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010;19:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero D.E., Cunha C.B. Evaluation of quality of epidemiological and demographic variables in the Live Births Information System, 2002. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23:701–714. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000300028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menezes A.M.B., da Costa J.D., Gonçalves H. Incidência e fatores de risco para tuberculose em Pelotas, uma cidade do Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 1998;1 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmaltz C.A.S., Sant’Anna F.M., Neves S.C. Influence of HIV infection on mortality in a cohort of patients treated for tuberculosis in the context of wide access to HAART, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b31e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston J.C., Shahidi N.C., Sadatsafavi M., Fitzgerald J.M. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freire D.N., Bonametti A.M., Matsuo T. Diagnóstico precoce e progressão da tuberculose em contatos. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2007;16:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vieira A.A., Ribeiro S.A. Abandono do tratamento de tuberculose utilizando-se as estratégias tratamento auto-administrado ou tratamento supervisionado no Programa Municipal de Carapicuíba, São Paulo, Brasil. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ntshangaa S.P., Rustomjeea R., Mabaso M.L.H. vol. 103. Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; South Africa: 2009. (Evaluation of directly observed therapy for tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal). 571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arcencio R.A., Oliveira M.F., Villa T.C.S. Internações por tuberculose pulmonar no Estado de São Paulo no ano de 2004. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2007;2:409–417. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232007000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sousa L.M.O., Pinheiro R.S. Óbitos e internações por tuberculose não notificados no município do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011;45:31–39. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selig L.B. Óbitos atribuídos à tuberculose no estado do Rio de Janeiro. J Bras Pneumol. 2004;30:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira GP. Subnotificação dos óbitos por tuberculose: associação com indicadores socioeconômicos e de desempenho dos programas municipais de controle. MSc dissertation. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; 2010.