Abstract

Context and objectives

The appropriate use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the perioperative period may reduce the rate of infection in the surgical site. The purpose of this review was to evaluate adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

Methods

The present systematic review was performed according to the Cochrane Collaboration methodology. The databases selected for this review were: Medline (via PubMed), Scopus and Portal (BVS) with selection of articles published in the 2004–2014 period from the Lilacs and Cochrane databases.

Results

The search recovered 859 articles at the databases, with a total of 18 studies selected for synthesis. The outcomes of interest analyzed in the articles were as follows: appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis (ranging from 70.3% to 95%), inappropriate indication (ranging from 2.3% to 100%), administration of antibiotic at the correct time (ranging from 12.73% to 100%), correct antibiotic choice (ranging from 22% to 95%), adequate discontinuation of antibiotic (ranging from 5.8% to 91.4%), and adequate antibiotic prophylaxis (ranging from 0.3% to 84.5%).

Conclusions

Significant variations were observed in all the outcomes assessed, and all the studies indicated a need for greater adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

Keywords: Antibiotic prophylaxis, Antimicrobial prophylaxis, Guideline adherence, Surgical patient

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed, through an international consensus statement, a Surgical Safety Checklist aimed to improve the safety of patients undergoing surgical procedures, since safety measures are often not adequately implemented, even in referral centers.1

The morbimortality associated to postoperative infections deserves special attention in patient care. Also, with the use of improper antibiotic prophylaxis patients are not adequately protected, may suffer adverse effects of these drugs, and more resistant strains can be selected.

Surgical infection remains an issue, being the third most frequent cause of nosocomial infection and affecting 14–16% of hospitalized patients. In surgical patients, postoperative wound infection is the most common cause of nosocomial infection, accounting for 77% of deaths. Patients who develop infection double the chance of dying compared to patients who undergo the same procedures without infection.2 A nation-wide study conducted by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, in 1999, obtained a rate of surgical site infection (SSI) of 11% of the total surgical procedures assessed. This rate is more significant because of the factors related to the hospitalized population and the procedures carried out in health services.3

Antibiotic prophylaxis is aimed to reduce the incidence of SSI by preventing the development of infection caused by organisms that colonize or contaminate the surgical site. The main target of antibiotic prophylaxis is the wound. Antibiotics are administered to the patient to reduce the bacterial load, so that it does not overwhelm the host natural defenses, causing infection.4 The adequate use of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis can reduce the rate of SSI in up to 50%.1

Efforts have been undertaken to establish guidelines for the appropriate use of antibiotic prophylaxis. These guidelines are designed to provide professionals with a standardized approach to rational, safe and effective use of antimicrobial agents for the prevention of SSI, and their content is based on current available clinical evidence, besides emerging issues.5

Although the principles of antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery are clearly established and several guidelines have been published, the implementation of these guidelines has been impaired by multiple factors.6 Some possible reasons include the difficulty encountered by professionals to update their knowledge, their dependence on habits originated in clinical practice rather than in evidence, the lack of policies, and failures in the implementation of norms and institutional guidelines.7

In view of the aforementioned, the present review aimed to assess the adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, by analyzing studies on the application of local, national and/or international guidelines.

Material and methods

The present Systematic Review was developed according to the methodology recommended by the Brazilian Cochrane Collaboration center and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitário Gaffrée and Guinle/UNIRIO.

The review included the articles published from July 2004 to July 2014, based on the following databases: Medline (via PubMed), Scopus and Portal da BVS (with selection of Lilacs and Cochrane databases). The search strategies were designed according to the specificity of each database, considering three main research indexes: title, abstract, and subject for Scopus and Lilacs, and title and topic for Pubmed. Whenever possible, the strategies were elaborated with the controlled vocabulary subject descriptors of Mesh/Medline and DeCs/BVS. Besides, free text terms searched in the main periodicals, as well as in references, abstracts and comments of related articles were used to increase the sensitivity of the search. The search was combined with Boolean operators “OR” for addition and “AND” for the list of terms. No idiom filters were applied.

The terms used in the search were translated into controlled vocabulary according to the research variables and the following representation of subject and free text terms was observed: Antibiotic prophylaxis, prophylactic antibiotic, antimicrobial prophylaxis, prophylaxis, surgery, surgical patient, surgical wound infection, postoperative wound infection, surgical procedure, operative, operative surgical procedure, guideline adherence, evaluation, adherence, surveillance, appropriate, appropriateness.

-

1.Inclusion criteria for selection of articles were:

-

•Population: studies in patients aged 18 or over;

-

•Articles portraying themes related to adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis;

-

•Studies on surgical procedures on the following specialties: gynecology, urology, vascular surgery, otorhinolaryngology, neurosurgery, thoracic surgery, general surgery, plastic surgery.

-

•

-

2.Exclusion criteria for selection of articles were:

-

•Articles whose main purpose was to correlate antibiotic prophylaxis to the occurrence of SSI;

-

•Articles exclusively or mostly on:

-

∘Pediatric patients;

-

∘Emergency procedures and/or trauma;

-

∘Endoscopic exams;

-

∘Surgical procedures of the following specialties: cardiac surgery, orthopedics, odontology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, dermatology, ophthalmology and obstetrics.

-

∘

-

•

The outcomes assessed in the 18 selected studies were as follows: (1) appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis; (2) inappropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis; (3) antibiotic administration at the correct time; (4) correct antibiotic choice; (5) adequate discontinuation of antibiotic; and (6) adequate antibiotic prophylaxis.

The outcomes of interest analyzed in the articles were considered appropriate or not, according to the observance of predefined parameters of antibiotic prophylaxis protocols/guidelines adopted in each article. The antibiotic prophylaxis was considered adequate when there was adherence to the criteria established in the guidelines adopted in each study.

Each article was assessed by two independent reviewers and all data were extracted by these reviewers. Details on population, themes, type of surgical procedures, appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis, inappropriate indication, antibiotic administration at the correct time, correct antibiotic choice, adequate discontinuation of antibiotic, and adequate antibiotic prophylaxis were independently extracted. A third reviewer was consulted in the event of a disagreement.

Results

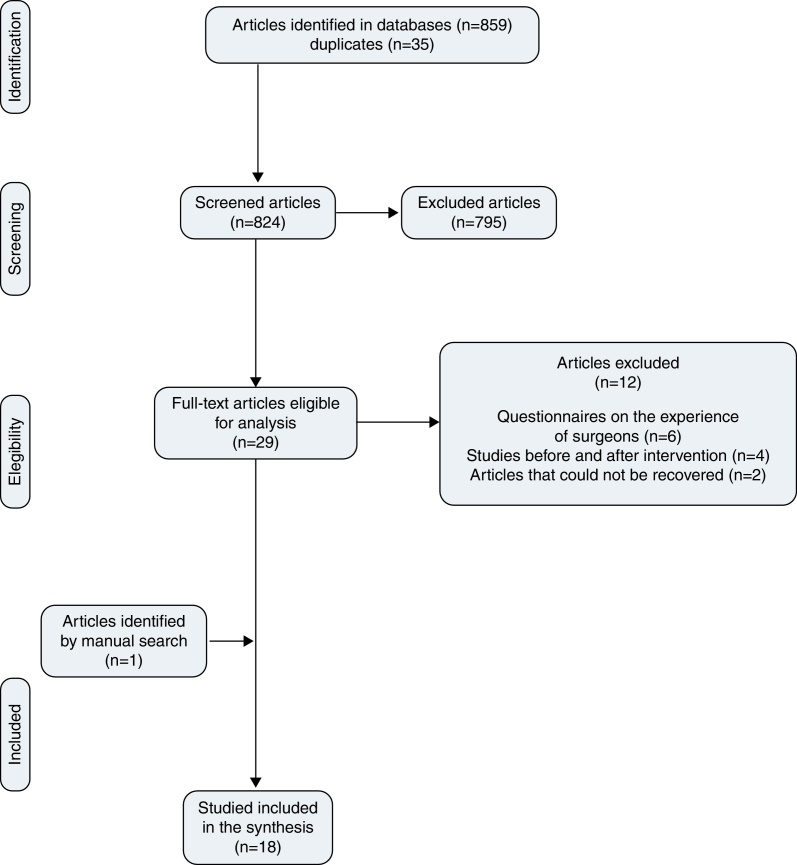

The terms used in the search of databases can be seen in Table 1.The search recovered 859 articles that were stored in the EndNote Web reference management software, and 35 articles were found to be duplicates. After assessment of the titles and abstracts of the 824 articles identified, 795 articles were excluded because they included unrelated or unsuitable subjects. Of the 29 articles eligible for analysis, 12 full-text articles were excluded:

-

•

Six articles concerned questionnaires on the experience of surgeons in antibiotic prophylaxis. The purpose of this review was to assess adherence to guidelines in surgical procedures that were actually performed.

-

•

Four articles concerned studies on adherence to guidelines before and after educational interventions.

-

•

Two non-recovered articles: (1) OR Manager. 2005 Jan;21(1):22–3 (this reference does not inform names of the authors, only the Journal); (2) Kayashima K, and K. Kataoka, 2013, [Setting appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis before skin incision]: Masui, v. 62, p. 745–50 (article in Japanese).

Table 1.

Search strategies.

| Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (Virtual health library): (tw:(mh:“guideline adherence” OR mh:“fidelidade a diretrizes” OR evaluation OR avaliação OR adherence OR aderência OR surveillance OR vigilância OR appropriate OR apropriada OR appropriateness OR adequação)) AND (tw:(mh:“antibiotic prophylaxis” or antibiotic prophylaxis or prophylactic antibiotic or antimicrobial prophylaxis or prophylaxis or mh:“antibioticoprofilaxia” or antibioticoprofilaxia or antibiótico profilático or profilaxia antimicrobiana or profilaxia)) AND (tw:(mh:“surgery” or cirurgia or surgical patient or paciente cirúrgico or mh:“surgical wound infection” or surgical wound infection or postoperative wound infection* or mh:“infecção da ferida operatória” or “infecção da ferida operatória” or “infecção de ferimento pós-operatório” or surgical procedure or mh:“surgical procedure, operative” or operative surgical procedure or procedimentos cirúrgicos operatórios)) | 223 articles recovered: Central (174 articles), Lilacs (19 articles), NHS-EED (8 articles), DARE (6 articles), CDSR (1 article) |

| PubMed: ((((((“guideline adherence”[ti] OR guideline adherence[mh] OR evaluation[ti] OR adherence[ti] OR surveillance[ti] OR appropriate[ti] OR appropriateness[ti]))) AND ((Antibiotic prophylaxis[mh] OR “Antibiotic prophylaxis”[ti] OR “prophylactic antibiotic”[ti] OR “antimicrobial prophylaxis”[ti] OR prophylaxis[ti])) AND ((surgery[ti] OR “surgical patient”[ti] OR Surgical wound infection*[ti] OR Surgical wound infection[mh] OR postoperative wound infection*[ti] OR Surgical procedure*[ti] OR surgical procedure, operative[mh] OR operative surgical procedure*[ti]))) AND “last 10 years”[PDat])) NOT (((“all child”[Filter] OR “all infant”[Filter]))) | 219 articles recovered |

| Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“guideline adherence” OR evaluation OR adherence OR surveillance OR appropriate OR appropriateness))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY((“Antibiotic prophylaxis” OR “prophylactic antibiotic” OR “antimicrobial prophylaxis” OR prophylaxis))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY((surgery OR “surgical patient” OR surgical wound infection* OR postoperative wound infection* OR surgical procedure* OR “surgical procedure operative” OR “operative surgical procedure”))) AND (EXCLUDE(SUBAREA, “DENT”)) | 382 articles recovered |

One article obtained by manual search was added to the remaining full 17 articles, totaling 18 studies that were included in the synthesis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature search for studies.

The general characteristics of the reviewed studies are described in Table 2. Of the studies included in the synthesis, nine were conducted in Europe, four in Asia, two in Oceania and three in America. Regarding the study designs, there were eight cross-sectional studies and 10 cohort studies (seven prospective and three retrospective), with levels of evidence ranging from IV to VI.8 The sample sizes ranged between 84 and 545,322 individuals. Regarding the surgical specialties contemplated, the studies involved General surgery (four studies), Otorhinolaryngology (one), Gynecology (two), Urology (one), and 10 studies involved multiple specialties (General surgery, Cardiac surgery, Neurosurgery, Gynecology-obstetrics, Ophthalmology, Orthopedics, Otorhinolaryngology, Urology, Vascular, Plastic, Thoracic and Oral and maxillofacial surgery).

Table 2.

General characteristics of the selected studies.

| Author/year/place | Study design | Level of evidence | Sample | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Gul et al., 2005)7 Malaysia |

Cross-sectional | VI | 419 | January to May 2002 |

| (Colgan et al., 2005)9 Australia |

Retrospective cohort | IV | 420 | August/2011–July/2002 |

| (Askarian et al., 2006)10 Iran |

Prospective cohort | IV | 1000 | February to July/2004 |

| (Castella et al., 2006)11 Italy |

Cross-sectional | VI | 803 | October to November/2003 |

| (Bull et al., 2006)12 Australia |

Retrospective cohort | IV | 10,643 | January/2003–September/2004 |

| (Fennessy et al., 2006)13 Ireland |

Prospective cohort | IV | 131 | 2004 |

| (Sae-Tia and Chongsomchai, 2006)14 Thailand |

Prospective cohort | IV | 250 | August 2004–February/2005 |

| (Malavaud et al., 2008a)15 France |

Cross-sectional | VI | 84 | 2005 |

| (Tourmousoglou et al., 2008)6 Greece |

Prospective cohort | IV | 890 | January to October/2000 |

| (Malavaud et al., 2008b)16 France |

Cross-sectional | VI | 100 | July to December/2006 |

| (Mahdaviazad, 2011)17 Iran |

Cross-sectional | VI | 365 | April to September/2010 |

| (Meeks et al., 2011)18 United States |

Retrospective cohort | IV | 517 | July/2006–December/2007 |

| (Durando et al., 2012)19 Italy |

Prospective cohort | IV | 717 | November 15 to December 15/2007 |

| (Hohmann et al., 2012)20 Germany |

Prospective cohort | IV | 5064 | June/2008 to April/2009 |

| (Pittalis et al., 2013)21 Italy |

Prospective cohort | IV | 2835 | April to June/2008 |

| (Machado-Alba et al., 2013)22 Colombia |

Cross-sectional | VI | 211 | April 1st to June 30/2010 |

| (Napolitano et al., 2013)23 Italy |

Cross-sectional | VI | 382 | October/2009 to January/2012 |

| (Wright et al., 2013)24 United States |

Cross-sectional | VI | 545,322 | 2003–2010 |

The articles included used the following guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis, considering that some studies adopted more than one type of guideline/protocol:

-

•Local and/or national guidelines:

-

∘Gul et al., 2005/Malaysia/N = 419;

-

∘Colgan et al., 2005/Australia/N = 420;

-

∘Castella et al., 2006/Italy/N = 803;

-

∘Durando et al., 2012/Italy/N = 717;

-

∘Bull et al., 2006/Australia/N = 10,643;

-

∘Malavaud et al., 2008a and 2008b/France/N = 84 and N = 100;

-

∘Tourmousoglou et al., 2008/Greece/N = 890, Pittalis et al., 2013/Italy/N = 2835;

-

∘Napolitano et al., 2013/Italy/N = 382;

-

∘Wright et al., 2013/United States/N = 545,322, Machado-Alba et al., 2013/Colombia/N = 211;

-

∘Hohmann et al., 2012/Germany/N = 5064.

-

∘

-

•Guideline of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/Surgical Infection Society (SIS)/Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA):

-

∘Askarian et al., 2006/Iran/N = 1000;

-

∘Fennessy et al., 2006/Ireland/N = 131;

-

∘Mahdaviazad et al., 2011/Iran/N = 365.

-

∘

-

•Guideline of the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC):

-

∘Machado-Alba et al., 2013/Colombia/N = 211;

-

∘Colgan et al., 2005/Australia/N = 420;

-

∘Castella et al., 2006/Italy/N = 803;

-

∘Durando et al., 2012/Italy/N = 717.

-

∘

-

•Guideline of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG):

-

∘Sae-Tia and Chongsomchai, 2006/Thailand/N = 250;

-

∘Wright et al., 2013/United States/N = 545,322.

-

∘

-

•Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP):

-

∘Pittalis et al., 2013/Italy/N = 2835;

-

∘Meeks et al., 2011/United States/N = 517.

-

∘

-

•Several international South American protocols:

-

∘Machado-Alba et al., 2013/Colombia/N = 211.

-

∘

Significant variations were observed in all assessed outcomes of interest, as described in Table 3 and listed below:

-

•

For the outcome appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis, of the 18 studies selected, only five addressed this aspect. These studies contained a prevalence of 70.3% to 95% of adequate indication (N= 717 and 2835, respectively). The surgical specialties studied in the five articles that addressed this outcome were exclusively Urology (one article), exclusively General Surgery (one article), exclusively Gynecology (one article), and multiple specialties (two articles).

-

•

Six studies addressed the outcome inappropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis, with results varying from 2.3% to 100% (N = 545,322 and 12 colorectal surgeries, respectively). The surgical specialties studied in the six articles that addressed this outcome were: exclusively General Surgery (two articles), exclusively Gynecology (one article), and multiple specialties (three articles).

-

•

Regarding the outcome administration of antibiotic at the correct time, it was assessed in 14 studies, with percentages ranging from 12.73% to 100% (N = 420 and 890, respectively). The surgical specialties studied in the 14 articles that addressed this outcome were: exclusively General Surgery (five articles), exclusively Otorhinolaryngology (one article), exclusively Urology (one article), and multiple specialties (seven articles).

-

•

Correct antibiotic choice was described in 10 studies, with values ranging from 22% to 95% (N = 97 in cholecystectomies and 803, respectively). The surgical specialties studied in the 10 articles that addressed this outcome were: exclusively General Surgery (four articles), exclusively Urology (one article), and multiple specialties (five articles).

-

•

The outcome adequate discontinuation of antibiotic was described in nine studies, ranging between 5.8% and 91.4% (N = 1000 and 100, respectively). The surgical specialties studied in the nine articles that addressed this outcome were: exclusively General Surgery (four articles) and multiple specialties (five articles).

-

•

For the outcome adequate antibiotic prophylaxis, 13 studies showed percentages ranging from 0.3% to 84.5% (N = 1000 and 2835). The surgical specialties studied in the 13 articles that addressed this outcome were: exclusively General Surgery (two surgeries), exclusively Urology (one article), exclusively Gynecology (one article), and multiple specialties (nine articles).

Table 3.

Main results regarding the analyzed outcomes of interest.

| Author/year/place | Appropriate indication | Inappropriate indication | Administration at the correct time | Correct choice | Appropriate discontinuation | Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Gul et al., 2005) Malaysia |

ND | ND | 98% | 87%A 22%B 84.3%C |

20%A 48%B 69%C |

ND |

| (Colgan et al., 2005) Australia |

ND | ND | 12.73% | ND | ND | ND |

| (Askarian et al., 2006) Iran |

ND | 98% | ND | ND | 5.8% | 0.3% |

| (Castella et al., 2006) Italy |

ND | ND | 84% | 95% | 80% | ND |

| (Bull et al., 2006) Australia |

ND | ND | 76.4% | 53.3% | ND | 81.1% |

| (Fennessy et al., 2006) Ireland |

ND | 5%D, 30%E, 66%F 80%G, 96%H, 100%A |

40% | ND | ND | ND |

| (Sae-Tia and Chongsomchai, 2006) Thailand |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 75.2% |

| (Malavaud et al., 2008a) France |

88.1% | ND | 72.9% | 91.9% | ND | 58.3% |

| (Tourmousoglou et al., 2008) Greece |

ND | 19% | 100% | 70% | 36.3% | 36.3% |

| (Malavaud et al., 2008b) France |

85% | ND | 39.7% | 82.8% | 91.4% | 42% |

| (Mahdaviazad, 2011) Iran |

ND | 64.6% | 61.1% | 25.4% | 29.4% | 10.13% |

| (Meeks et al., 2011) United States |

ND | ND | 79% | 65% | 82% | 62% |

| (Durando et al., 2012) Italy |

70.3% | ND | 75.7% | ND | ND | 35.5% |

| (Hohmann et al., 2012) Germany |

ND | ND | ND | ND | 67.1% | 70.7% |

| (Pittalis et al., 2013) Italy |

95% | 5% | 50% | 84.5% | 48% | 84.5% |

| (Machado-Alba et al., 2013) Colombia |

ND | ND | 45.5% | ND | ND | 44.5% |

| (Napolitano et al., 2013) Italy |

ND | ND | 53.4% | 25.5% | ND | 18.1% |

| (Wright et al., 2013) United States |

87.1% | 2.3% | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Analyzed outcomes:

Appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Inappropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Antibiotic administration at the correct time.

Correct antibiotic choice.

Appropriate discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Adequate antibiotic prophylaxis = adherence to the protocols of antibiotic prophylaxis adopted.

ND = not described.

Considered appropriate/inappropriate, correct and adequate when the predefined parameters of antibiotic prophylaxis protocols adopted in each article are observed.

Surgeries – A: colorectal, B: cholecystectomies, C: inguinal hernioplasties, D: biopsies, E: head and neck, F: gastroduodenal, G: laparoscopic cholecystectomies, H: vascular.

Discussion

Antibiotic prophylaxis is aimed to reduce the incidence of SSI. Ideally, it should ensure that an adequate concentration of an appropriate antimicrobial agent is present in the blood, tissues, and surgical wound during the entire time the incision is open and at risk of bacterial contamination. The selection and duration of antibiotic prophylaxis should cause the least possible impact on the patient microbiota.25 Therefore, it is extremely important to observe the guidelines for administration of a correct antibiotic prophylaxis.

It is important to consider human factors as a cause of non-adherence to prophylaxis protocols. The physicians were used to follow their ‘own guidelines’ as they had been trained in a wrong way in the past. Although guidelines are revised regularly, it is observed that there is a lack of awareness of these revised versions by doctors. It is a challenge to disseminate evidence-based knowledge systematically into clinical practice.6 The effect on clinical behavior is also related to financial issues, such as malpractice insurance costs and managed care systems.26 The busy practitioner who seeks an excuse for the difficulty he or she faces in keeping up to date with evidence-based medicine should rely on formal clinical guidelines as an acceptable means of adopting safe clinical practice. This will hopefully reduce the haphazard abuse of antibiotic administration and its undesirable consequences.7

Because of the diversity of guidelines adopted in the different studies, it has been difficult to compare adherence to guidelines regarding the outcomes of interest in the present review. The comparisons of results between the studies should be made with caution, as the discrepancies can be partly attributed to factors such as: populations of different studies, studies conducted in different countries, comparison of studies on a single type of surgical procedure or between very different surgical specialties, different methods used in the studies, different guidelines of antibiotic prophylaxis adopted (including in the same study), partial analysis of outcomes of interest in some studies (only in the cases where the administration of antibiotics was appropriately indicated), and the possibility of incomplete records in patient charts. Levy et al.,27 in their report, have already observed that the internal validity (methodological rigor) and external validity (generalizability) of studies on surgical antibiotic prophylaxis are poor and even the results may be context-sensitive.

The outcome adequate antibiotic prophylaxis was the second outcome most described in the reviewed studies, with 13 studies addressing this parameter. Antibiotic prophylaxis was considered adequate when there was adherence to the criteria established in the guidelines adopted in each study. Even when adherence to guideline was 84% in one of the studies, antibiotic prophylaxis was considered inadequate in all the studies, which is consistent with Bratzler28 who states that, although the administration of chemoprophylaxis in surgery is well-accepted and standardized, surgeons not always adhere to the existing guidelines. According to the same author, given the wide range of evidence-based recommendations, appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis should be a practice relatively easy to implement. However, many patients are still undergoing surgeries without a satisfactory antibiotic prophylaxis.

Of all the outcomes defined for analysis in this review, the one that was least addressed by the selected studies was appropriateness of indication of antibiotic prophylaxis, which was addressed in five studies only. Despite the prevalence of more than 70.3% of the studies, and of the lower variability in the results when the studies were compared, in none of them appropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis was satisfactory. The second outcome less evaluated in the studies was inappropriate indication of antibiotic prophylaxis and it showed the highest variability among studies. The results obtained for the two above-mentioned outcomes demonstrate that the practices adopted do not observe the recommendations made by Tavares,29 who reports that the prophylactic use of antimicrobials in surgery is justified if there is high risk of surgical wound infection, or if this infection may generate severe consequences. The McDonnell Norms Group30 addresses adverse consequences such as direct toxicity, change in the normal microbiota, and promotion of bacterial resistance, when antibiotics are inappropriately prescribed.

The nine studies where appropriate discontinuation of antibiotic was described also showed a significant variation, ranging from 5.8% to 91.4%. The adherence of the studies with this outcome was not considered satisfactory and is not consistent with authors that claim that a more prolonged administration of prophylactic antibiotics did not favor the prevention of surgical wound infection, and may encourage the development of microbial resistance, in addition to being costly to patients, increasing the direct costs of care.31, 32

Of the 18 studies reviewed, 10 described the correct antibiotic choice, and also showed discrepant results, with values ranging from 22% to 95% and poor adherence to the guidelines. Bratzler et al.5 claim that the antimicrobial agent selected must be active against the most common pathogens that occur in the surgical site, considering the safety profile and patient allergy to certain antibiotics. It is desirable that the antibiotic chosen be cheap, of low toxicity and with a half-life sufficiently prolonged to maintain adequate concentration until the wound has been closed.31

Most studies selected analyzed the outcome administration of antibiotic at the correct time. Out of the 14 studies included, only one showed 100% adherence to the adopted guideline, while the remaining 13 did not show adequate results, in disagreement with the current regulations. According to Bratzler,25 antibiotic prophylaxis aims to achieve blood and tissue levels of the drug that exceed the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the microorganisms likely to be encountered. Therefore, antibiotics should be administered at the correct time. The success of antimicrobial prophylaxis requires the availability of the drug at the surgical site before contamination occurs.5 It is important to stress that the moment considered appropriate for antibiotic administration varied between the guidelines adopted in the studies reviewed.

After analysis of the studies selected for this review, the great variability of methods used in the study of the subject, and in most cases the design of the study generated low levels of evidence (IV and VI), with the absence of randomized clinical trials on the theme.

Antibiotics cannot be indiscriminately administered to any surgical patient in order to prevent postoperative infections. Such use is not only unnecessary in many surgical situations but it also makes the treatment more expensive and contributes to the selection of resistant organisms. In addition, it can be harmful, due to the side-effects of antibiotics. It is up to the medical professionals involved to observe the essential principles of asepsis and antisepsis, recommending the prophylactic use of antibiotics for the surgery, choose the adequate drug, administer at the correct time and discontinue antibiotic prophylaxis at the appropriate time.29 According to Salkind,33 the professionals that give support to surgical procedures have the opportunity to interfere in order to reduce the incidence of SSI when they understand which surgeries require the administration of prophylactic antibiotics, which antibiotic is appropriate, and when it should be administered and discontinued.

Finally, we observed that all the studies reviewed concluded that greater adherence to the guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis is required. It is clearly necessary that hospital managers and doctors become involved in initiatives aimed to the application of guidelines.23 Therefore, surgeons and anesthesiologists, the professionals who decisively contribute to the reduction of postsurgical infectious complications of patients, are essential in this scenario.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to our parents, spouses and everyone who contributed to the completion of this review, and especially to Letícia Gouvêa Cyro de Castro, for the assistance in formatting this text.

References

- 1.WHO. Guidelines for Safe Surgery 2009: safe surgery saves lives. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598552_eng.pdf [accessed on 14.10.14]. [PubMed]

- 2.Mendes F.F., Carneiro A.F. In: Qualidade e Segurança em Anestesiologia. Salman F.C., Diego L.A.S., Silva J.H., Moraes J.M.S., Carneiro A.F., editors. Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia; Rio de Janeiro: 2012. Infecção no paciente cirúrgico: como podemos contribuir para a prevenção? pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Critérios Nacionais de Infecções Relacionadas à Assistência à Saúde. Available at: http://www20.anvisa.gov.br/segurancadopaciente/images/documentos/livros/Livro2-CriteriosDiagnosticosIRASaude.pdf [accessed on 19.06.15].

- 4.Hall C., Allen J., Barlow G. Antibiotic prophylaxis. Surgery. 2012;30:651–658. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratzler D.W., Dellinger E.P., Olsen K.M., Perl T.M., Auwaerter P.G., Bolon M.K. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:195–283. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tourmousoglou C.E., Yiannakopoulou E.Ch., Kalapothaki V., Bramis J., St Papadopoulos J. Adherence to guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in general surgery: a critical appraisal. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:214–218. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gul Y.A., Hong L.C., Prasannan S. Appropriate antibiotic administration in elective surgical procedures: still missing the message. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:104–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melnyk B.M., Fineout-Overholt E., editors. Evidencebased practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2005. Making the case for evidence-based practice; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colgan S.J., Mc Mullan C., Davies G.E., Sizeland A.M. Audit of the use of antimicrobial prophylaxis in nasal surgery at a specialist Australian hospital. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:1090–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Askarian M., Moravveji A.R., Mirkhani H., Namazi S., Weed H. Adherence to American Society of Health-System Pharmacists surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines in Iran. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:876–878. doi: 10.1086/506405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castella A., Charrier L., Di Legami V., Pastorino F., Farina E.C., Argentero P.A. Surgical site infection surveillance: analysis of adherence to recommendations for routine infection control practices. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:835–840. doi: 10.1086/506396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bull A.L., Russo P.L., Friedman N.D., Bennett N.J., Boardman C.J., Richards M.J. Compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis: reporting from a statewide surveillance programme in Victoria, Australia. J Hosp Infect. 2006;63:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fennessy B.G., O'sullivan M.J., Fulton G.J., Kirwan W.O., Redmond H.P. Prospective study of use of perioperative antimicrobial therapy in general surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7:355–360. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sae-Tia L., Chongsomchai C. Appropriateness of antibiotic prophylaxis in gynecologic surgery at Srinagarind Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:2010–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malavaud S., Bonnet E., Atallah F., El Farsaoui R., Roze J., Mazerolles M. Evaluation of clinical practice: audit of prophylactic antibiotics in urology. Prog Urol. 2008;18:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malavaud S., Bonnet E., Vigouroux D., Mounet J., Suc B. Prophlactic antibiotic use in gastro-intestinal surgery: an audit of current practice. J Chir (Paris) 2008;145:579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0021-7697(08)74689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahdaviazad H., Masoompour S.M., Askarian M. Iranian surgeons’ compliance with the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists guidelines: antibiotic prophylaxis in private versus teaching hospitals in Shiraz, Iran. J Infect Public Health. 2011;4:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meeks D.W., Lally K.P., Carrick M.M., Lew D.F., Thomas E.J., Doyle P.D. Compliance with guidelines to prevent surgical site infections: as simple as 1-2-3? Am J Surg. 2011;201:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durando P., Bassetti M., Orengo G., Crimi P., Battistini A., Bellina D. Adherence to international and national recommendations for the prevention of surgical site infections in Italy: results from an observational prospective study in elective surgery. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:969–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hohmann C., Eickhoff C., Radziwill R., Schulz M. Adherence to guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery patients in German hospitals: a multicentre evaluation involving pharmacy interns. Infection. 2012;40:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pittalis S., Ferraro F., Piselli P., Ruscitti L.E., Grilli E., Lanini S. Appropriateness of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis in the Latium region of Italy, 2008: a multicenter study. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2013;14:381–384. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado-Alba J.E., Morales-Plaza C.D., Solarte M.J. Adherence to prophylactic antibiotic therapy of thoraco-abdominal interventions in Hospital Universitario San Jorge Pereira. Rev Cienc Salud. 2013;11:205–216. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Napolitano F., Izzo M.T., Di Giuseppe G., Angelillo I.F., Collaborative Working Group Evaluation of the appropriate perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in Italy. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e79532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright J.D., Hassan K., Ananth C.V., Herzog T.J., Lewin S.N., Burke W.M. Use of guideline-based antibiotic prophylaxis in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1145–1153. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a8a36a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bratzler D.W., Houck P.M. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am J Surg. 2005;189:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis D.A., Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:408–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy S.M., Phatak U.R., Tsao K., et al. What is the quality of reporting of studies of interventions to increase compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bratzler D.W., Houck P.M., Richards C., Steele L., Dellinger E.P., Fry D.E. Use of antimicrobial prophylaxis for major surgery: baseline results from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Arch Surg. 2005;140:174–182. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tavares W. 3rd ed. rev. Editora Atheneu; São Paulo: 2014. Antibióticos e quimioterápicos para o clínico. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell Norms Group Antibiotic overuse: the influence of social norms. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano-Heranz R. Quimioprofilaxis en cirugía antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2006;19:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santana R.S., Viana A.C., Santiago J.S., Menezes M.S., Lobo I.M.F., Marcellini P.S. The cost of excessive postoperative use of antimicrobials: the context of a public hospital. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2014;41:149–154. doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912014000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salkind A.R., Rao K.C. Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent surgical site infections. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:585–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]