Abstract

Novel strategies to combat the ever increasing burden of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) causing tuberculosis (TB) remains a global concern. The ability of MTB to sense and adapt to restricted iron conditions in the hostile environment is essential for their survival and confers the basis of their success as dreadful pathogen. The striking and clinically relevant virulence trait of MTB is its ability to form biofilms and adhere to the host cells. The present study elucidated the effect of iron deprivation on biofilm formation and cell adherence of Mycobacterium smegmatis, a non-pathogenic surrogate of MTB. Firstly, we showed that iron deprivation leads to enhanced cell sedimentation rate and altered colony morphology depicting alterations in cell surface envelope properties. We explored that biofilm formation and cell adherence to polystyrene surface as well as human oral epithelial cells were considerably reduced under iron deprivation both in presence of 2,2 BP (iron chelator) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14 strain. We further investigated that the potency of three first line anti-TB drugs (Isoniazid, Ethambutol, Rifampicin) to inhibit both biofilm formation and cell adhesion were enhanced under iron deprivation in contrast to the drugs when tested alone. Taken together, by virtue of the indispensability of iron for functional virulence traits in mycobacteria, iron deprivation strategies could be further exploited against this notorious human pathogen to explore novel drug targets.

Keywords: Iron, Morphology, Biofilm, Anti-TB drugs

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is among the major causes of mortality and morbidity in humans affecting nearly one third of the global population annually.1 One of the hallmarks of Mycobacterium species is the existence of complicated but unique cell envelop which makes them less permeable and rendering them drug resistant thereby differentiating from other class of bacteria.2 Therefore, to find novel strategies, address the issue of drug resistance, and surmount the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) infection still remains at priority.

Targeting iron homeostasis of the invading pathogens including MTB to impede the fast growing resistance has emerged as one of the strategies that have been efficiently adopted and widely gained prominence.3 The struggle for the limited amount of iron in the hostile environment is crucial for establishment of infection in MTB. Moreover, iron deprivation is already known to enhance the drug susceptibilities of known anti-TB drugs in mycobacteria.4 The present study aimed to add to the existing knowledge about the role of iron in survival and virulence of Mycobacterium smegmatis, a surrogate for MTB because of its close homology, fast growth and non-pathogenic nature. We showed that iron deprivation leads to altered cell surface properties, biofilm formation and cell adherence to polystyrene as well as human oral epithelial cells. All these unreported phenotypes and disrupted mechanisms are necessary for MTB to sustain virulence and represents alternative paradigm for antimycobacterial intervention.

Materials and methods

Materials

All media chemicals Middlebrook 7H9 broth, Middlebrook 7H10 agar, albumin/dextrose/catalase (ADC), and oleic acid/albumin/dextrose/catalase (OADC) supplements were purchased from BD Biosciences (USA). Tween-80, ethambutol (EMB), and isoniazid (INH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rifampicins, crystal violet, Tris–HCl, ferrozine, were purchased from Himedia (Mumbai, India). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), disodiumhydrogen orthophosphate (Na2HPO4), potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (KH2PO4), glycerol, Ferrous sulphate (FeSO4), were obtained from Fischer Scientific; methanol (CH3OH), TLC silica gel 60 F254 (20×20) was purchased from Merck. Chloroform (CHCl3) was purchased from CDH, sodium acetate, iodine balls were purchased from Qualigens.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Mycobacterium smegmatis, mc2155, was used as a parent wild-type strain and mutant Δ011-014 as exochelin siderophore mutant (mimicking iron deprivation) for all the experiments. Bacteria were maintained on 7H10 agar supplemented with 10% (v/v) oleic acid/albumin/dextrose/catalase (OADC; BD Difco) and grown in Middlebrook 7H9 (BD Biosciences) broth supplemented with 0.05% Tween-80 (Sigma), 10% albumin/dextrose/catalase (ADC; BD Difco), and 0.2% glycerol (Fischer Scientific) in 100 ml flasks (Schott Duran) and incubated at 37 °C till the OD600 is equal to 1.0. Stock cultures of log phase cells were maintained in 30% glycerol and stored at −80 °C.

Ferroxidase assay

Whole cell protein was extracted and protein concentration was determined by Lowry method to proceed for ferroxidase assay by using a method as previously described.5 Bacterial cells were grown in middlebrook 7H9 broth in the absence (control) and presence of 2,2 BP (iron deprivation) at concentration (35 μg/ml). The assay was performed by using ferrous sulfate as the electron donor and 3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-bis(4-phenylsulfonic acid)-1,2,4-triazine (ferrozine) as a chelator to specifically detect the ferrous iron remaining at the end of the reaction. Each assay mixture of 0.2 ml contained (50 mM Na-acetate buffer, pH 5, and 0.1–0.3 μg) protein extract, and the reaction was started by addition of 0.2 mM FeSO4. Samples were quenched by adding ferrozine at 3.75 mM, and the Fe(II) oxidation was determined by measuring the absorbance of residual Fe(II)-ferrozine at 570 nm by spectrophotometer.

Cell sedimentation

Cell sedimentation assay was performed as described elsewhere.6 Cultures at OD600 ∼ 1.0–1.4 of the control, iron deprived and mutant strains in 7H9 + ADC + glycerol + tween, were adjusted in triplicate to OD590 ∼ 1.0 and kept unshaken at 37 °C. At 3 and 22 h, the upper 1 ml was removed for OD590 measurements.

Colony morphology

Colony morphology was observed by adjusting the OD600 ∼ 0.1 of the M. smegmatis strains (control, iron deprived and mutant) in 1× PBS saline and spotting 5 μl on agar Plate 7H 10 + ADC + glycerol followed by incubation of the plates at 37 °C for 48 h. The images were observed by microscope at 10× magnification.6

Lipid extraction and thin layer chromatography (TLC)

Cells of M. smegmatis control and 2,2 BP treated at exponential phase were used for lipid extraction by modified Folch method.7, 8 Briefly, the cells were harvested at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Cells were homogenized in aqueous solution for 3 min and suspended in CHCl3 and CH3OH in ratio of (1:2). Cells were shaken well and centrifuged at 2000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Supernatant was transferred to another glass vial and then remaining CHCl3 was added and filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The extract was then washed with 0.88% KCl to remove the non-lipid contamination. The lower dense layer of chloroform containing lipid was taken by glass Pasteur pipette in 5 ml glass vial with Teflon capping. The vials are stored at 20 °C until further analysis. Extracted lipids were then resolved by TLC using aluminum-backed silica gel plates (silica gel 60 F254; Merck). The lipid extract obtained from control and 2,2 BP was loaded on TLC plate at a distance of 2 cm up from the plate end. Chloroform–methanol–water (65:25:4; v/v/v) was used for developing the plates. Developed chromatogram was dried at room temperature for 2 min and then exposed to iodine fumes generated by iodine crystal balls placed in glass chamber to visualize the lipids.

Biofilm formation and cell adhesion on polystyrene

M. smegmatis biofilm formation was estimated as described previously6, 9, 10 on 96-well polystyrene plates. Briefly, cells were grown in 7H9 middlebrook broth till the OD600 ∼ 1.0. 100 μl of media was dispensed to each well of the 96 well plates with or without addition of drug. Culture were then adjusted to 0.1 OD and diluted in the ratio of 1:100 in the middlebrook media and 100 μl of diluted culture was pipetted in each well of 96-well flat bottom microtitre plate and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The wells were rinsed twice with distilled H2O and 125 μl of 0.1% solution of the crystal violet was added. Plates were incubated for 10 min followed by washing with distilled H2O 2–3 times, dried and then observed under the light microscope at 100×. For quantitative assay of biofilm, 200 μl of 95% ethanol was added to each crystal violet stained well and plates were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Contents of each well were mixed by pipetting, and then 125 μl of the crystal violet/ethanol solution was transferred from each well to a separate well of an optically clear flat bottom 96-well plate and optical densities (OD) measured at 600 nm using spectrophotometer. Inhibition of biofilm was calculated as percentage inhibition/reduction in growth. For cell adhesion assay same procedure was followed except that primarily treated and non-treated cells were grown till OD600 1.0 and after washing the non-adhered cells, they were directly quantified through crystal violet without forming biofilm.

Adherence of Mycobacterium to human buccal epithelial cells

Cell adherence assay were developed on mycobacteria using a protocol described elsewhere with modifications.9, 11 Epithelial cells were obtained from mouth cavity of the author who voluntarily agreed to donate. The cells were washed 2–3 times in PBS and the pellets were then resuspended in PBS to give approximately (0.5 OD600) by using spectrophotometer. Bacterial cells were grown in middlebrook 7H9 broth under iron deprivation (35 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The culture was adjusted to give an approximately OD650 of 0.5, washed twice in PBS, centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm and resuspended in PBS. The test was performed by taking equal volumes of buccal epithelial cells (OD600 of 0.5) and bacterial suspensions that were mixed and incubated under shaking (120 rpm) at 37 °C for 2–3 h. After incubation, 2–3 μl of carbol fuchsin dye to stain Mycobacterium cells and crystal violet to stain epithelial cell were added to each tube and the mixture was gently shaken. 10 μl of the stained suspension were transferred to a glass slide, covered with cover-slip and examined under light microscope at 40×. A total of 50 epithelial cells were counted and the mean percentage of adherence was calculated using the number of bacteria added per 50 cells as denominator.12 Cells were scored as adherent when attached to at least 40% of the epithelial cells, while non-adherent when attached to less than 10% of the examined epithelial cells.13

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3). The results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using Student t-test where in only p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Amity University Haryana (reference no. AUH/EC/RP/2016/05).

Results and discussion

Iron deprivation leads to enhanced cell sedimentation rate and altered colony morphology

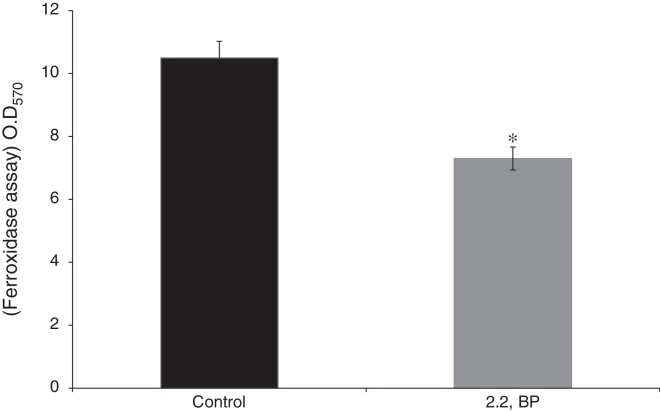

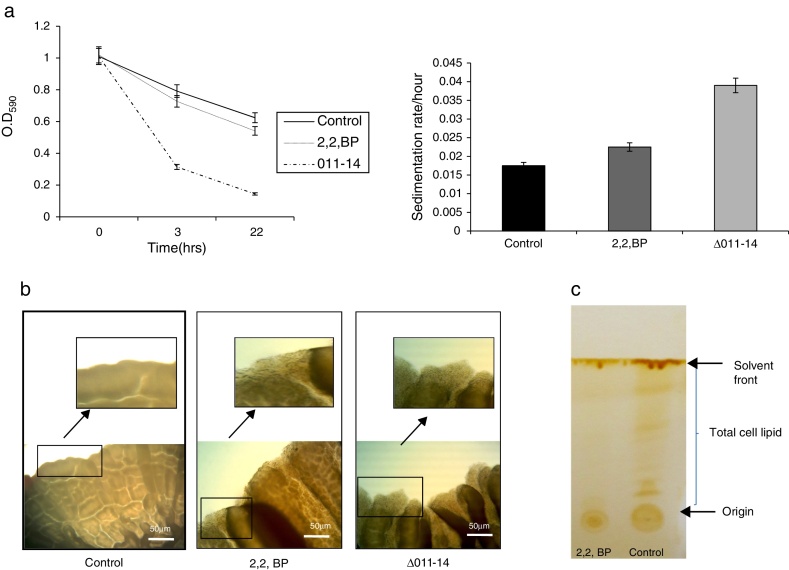

To ensure the iron deprived condition, firstly we did ferroxidase enzymatic assay to estimate the non-oxidized ferrous iron present in the reaction mixture. As expected, we found significantly reduced ferroxidase activity of M. smegmatis in the presence of an iron chelator 2,2 BP confirming the existing iron deprived condition (Fig. 1). Iron deprivation is known to disrupt the membrane integrity of mycobacteria.4 Therefore, we speculated that iron deprivation could further lead to alterations in cell surface properties. It is already known that cell sedimentation rate is inversely correlated with the cell surface hydrophobicity (CSH),6, 14 hence, measuring the cell sedimentation rate could give an estimate of any change in CSH leading to alterations in cell envelop. Our observations showed that cell sedimentation rate is considerably enhanced under iron deprivation (Fig. 2a). To further confirm, we used an exochelin siderophore mutant (Δ011-14) which mimics iron deficient condition. To our anticipation, the cell sedimentation rate was also enhanced in the siderophore mutant (Fig. 2a) strengthening the notion that CSH of envelop is also regulated by iron. These results confirm that CSH is diminished under iron deprivation corroborating with the earlier report of disrupted membrane integrity.6 This was also apparent from the fact that the colony morphology of control cell was distinct from that of the iron deprived and mutant (Δ011-14) cells. The control cell composed of smooth colony with defined border as compared to iron deprived cell and mutant (Δ011-14) which showed rough colony and undefined borders (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, these observations could also be due to the fact that mycobacteria have unique cell envelope known as mycomembrane comprising mycolic acids which are known to govern pathogenicity of mycobacteria and that iron deprivation may possibly affect mycolic acid synthesis as well. To ascertain whether the observed alteration in morphology could be attributed to changes in lipid profile, we performed a TLC of total cellular lipids under iron deprivation. The chromatogram (Fig. 2c) showed that total cellular lipids in control displayed various lipids classes at their respective positions contrary to the iron deprived lipids which were not detected at similar positions. However, further work is still needed to validate the disruption of mycolic acid synthesis under iron deprivation.

Fig. 1.

Effect of iron deprivation on ferroxidase activity. Enzyme ferroxidase activity quantified by using ferroxidase assay depicted as bar graph as described in material and methods in presence of 2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) in M. smegmatis. Mean of OD570nm ± SD of three independent sets of experiments are depicted on Y-axis and * depicts p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effect of iron deprivation on cell surface properties. (a) Relative sedimentation of M. smegmatis cells under iron deprivation. Left panel shows OD590 of untreated (control), 2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14 cells depicted on Y-axis with respect to time noted at 3 and 22 h on X-axis. Right panel depicts sedimentation rates per hour on Y-axis of 2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and mutant Δ011-14 cells with respect to control on X-axis, calculated by estimating the difference in OD590 from 0 till 22 h per unit time interval. Mean of three independent sets of experiments ± SD (shown by error bars) are depicted. (b) Altered colony morphology under iron deprivation. Colony morphology of control, iron deprived (2,2 BP) and mutant Δ011-14 cells were observed on 7H10-based medium. Corresponding area of colony borders were focused (10×-magnification) and one of the colony border depicted by an arrow is enlarged and shown in the inset. (c) Thin layer chromatogram showing altered total lipid profile under iron deprivation.

Iron deprivation affects biofilm formation

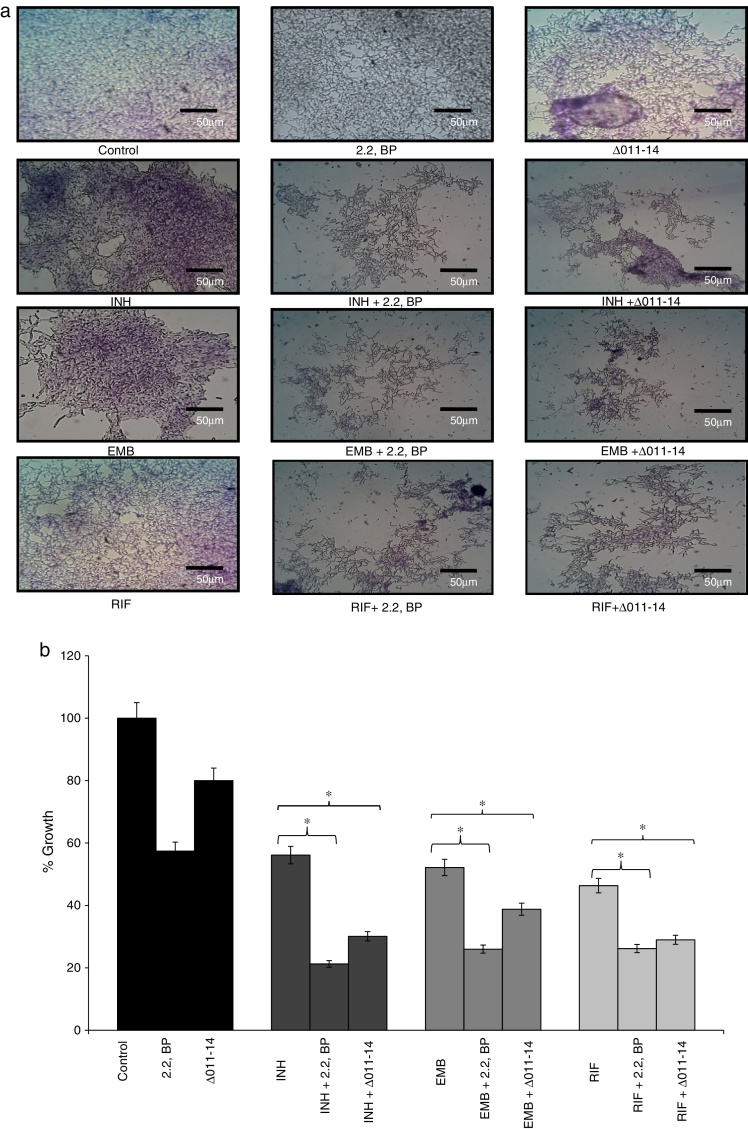

Biofilms are surface linked microbial colony enclosed in an extracellular polymeric matrix. This is one of the major key factors for MTB having implications on virulence, pathogenicity and thereby facilitates environmental survival.13 Biofilms render MTB highly resistant to anti-TB drugs hence searching for mechanisms counteracting biofilm formation is an attractive area of research. Moreover, reduced CSH under iron deprivation observed from this study and reduced CSH already known to negatively inhibit biofilm,6 compelled us to study the effect of iron deprivation on biofilm formation of M. smegmatis. For this, we performed biofilm formation assay as described in material and methods by both qualitative and quantitative methods. The crystal violet staining result showed that biofilm formation was significantly inhibited in iron deprived condition in contrast to control (Fig. 3a) thereby supporting the earlier observation of indispensability of exochelin siderophore in biofilm formation.15 We also tested whether iron deprivation could enhance the antibiofilm effect of known anti-TB drugs viz. isoniazid (INH), ethambutol (EMB) and rifampicin (RIF). Interestingly, we observed that iron deprivation (both 2,2 BP and Δ011-14) leads to enhanced biofilm inhibition in contrast to the inhibition caused by the drugs alone (Fig. 3a). The inhibitory biofilm effect under iron deprivation was further validated quantitatively which showed good correlation with our crystal violet staining result (Fig. 3b). This is also commensurate with our above finding of decreased CSH and altered colony morphology which may have made the Mycobacterium more susceptible to known antibiotics. Thus iron deprivation leads to diminished survival after exposure to known anti-TB drugs.

Fig. 3.

Effect of iron deprivation on mycobacterium biofilm. Iron deprivation (2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14) showing inhibited biofilm formation of Mycobacterium smegmatis in presence of three known anti-TB drugs, i.e. INH, EMB and RIF (1 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml). (a) Crystal violet staining showing the inhibited biofilm formation under iron deprivation (2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14). (b) Biofilm inhibition under iron deprivation (2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant (Δ011-14) in presence of three known anti-TB drugs, i.e. INH, EMB and RIF (1 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml) depicted as reduction in growth percent quantified by using crystal violet dye as bar graph. Mean of OD600 ± SD of three independent sets of experiments are depicted on Y-axis and * depicts p value <0.05.

Iron deprivation affects mycobacterial cell adherence to polystyrene surface and human oral epithelial cells

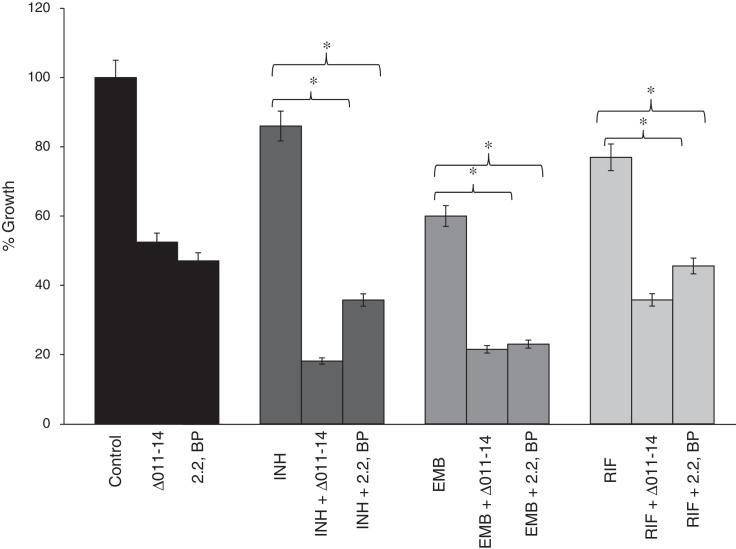

The compromised biofilm formation gives us clue to subsequently examine the effect of iron deprivation on cell adherence to an abiotic surface, being the primary step for biofilm formation. Cell adhesion is a gradual process that starts with adhesion, surface attachment, and maturation.16, 17, 18, 19 To our expectation, we found that iron deprivation causes diminished cell adherence of M. smegmatis to polystyrene surface (Fig. 4). This was revalidated when known anti-TB drugs viz. INH, EMB and RIF were tested for their efficacy to disrupt cell adhesion. Interestingly, we observed that iron deprivation leads to enhanced inhibition of cell adhesion to polystyrene surface in contrast to the inhibition caused by the drugs when tested alone (Fig. 4) implying impaired cell adhesion under iron deprivation. This observation becomes noteworthy from the fact that there is also a correlation between cell adhesion and mycolic acid which is well known to have implications on virulence and pathogenicity of MTB.20

Fig. 4.

Effect of iron deprivation on Mycobacterium cell adhesion. Iron deprivation (2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14) inhibits the cell adhesion of Mycobacterium smegmatis to microtiter polystyrene surface in presence of three known anti-TB drugs, i.e. INH, EMB and RIF (1 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml, 0.0625 μg/ml). Reduction in growth percent is quantified by using crystal violet dye and depicted as bar graph. Mean of OD600 ± SD of three independent sets of experiments are depicted on Y-axis and * depicts p value <0.05.

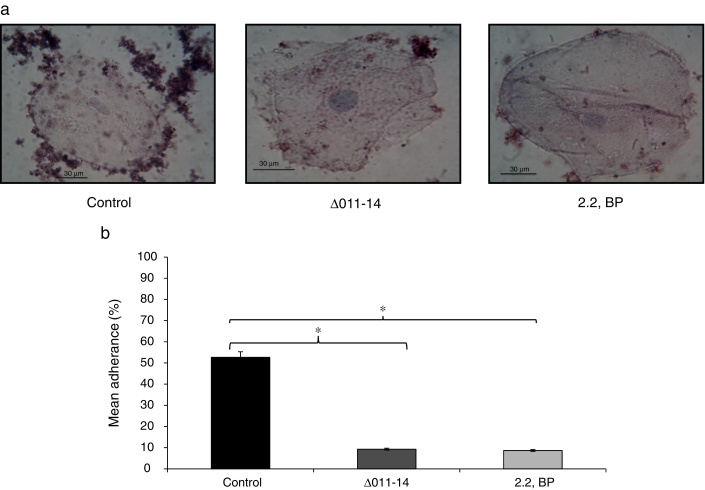

Inhibited cell adherence under iron deprivation on polystyrene surface and in order to verify our above finding, we checked the adherence of Mycobacterium on human buccal epithelial cells which is a critical step before invasion and pathogenesis. The ability of most invading bacterial pathogens including MTB to adhere the epithelial and mucosal surfaces is crucial for pathogenicity. Interestingly, we observed that iron deprivation (2,2 BP and siderophore mutant) showed inhibited adherence of Mycobacterium on epithelial cells as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 5a). To our expectation, the control cells showed mean percent adherence of 52.6% in comparison to the iron deprived and siderophore mutant cells which only showed mean percent adherence of 9.3% and 8.6%, respectively (Fig. 5b) Together, this study reinforce that iron deprivation inhibits potential virulence traits of M. smegmatis resulting in inhibition of biofilm formation and cell adherence.

Fig. 5.

Effect of iron deprivation on Mycobacterium cell adherence to epithelial cells. (a) Control (untreated) cells appeared adhered to human buccal epithelial cells while iron deprived cells (2,2 BP (35 μg/ml) and siderophore mutant Δ011-14) are not adhered to the epithelial cells (magnification 40×). (b) Mean percentage adherence of mycobacterial cells depicted as bar graphs showing OD600 ± SD of three independent sets of experiments on Y-axis and * depicts p value <0.05.

Conclusion

The data generated from this study clearly establishes the indispensability of iron for virulence traits of Mycobacterium. Thus targeting the pathways that require iron in Mycobacterium could be a novel and promising antitubercular strategy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Financial assistance in the form of Young Scientist award to Z.F. from Board of Research in Nuclear Sciences (BRNS), Mumbai (2013/37B/45/BRNS/1903) is deeply acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Sarman Singh and Prof. Graham F. Hatfull for providing M. smegmatis mc2155 reference strain and siderophore mutant as generous gifts respectively.

References

- 1.Ma J., Yang B., Yu S., et al. Tuberculosis antigen-induced expression of IFN-α in tuberculosis patients inhibits production of IL-1β. FASEB J. 2014;28:3238–3248. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-247056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hett E.C., Rubin E.J. Bacterial growth and cell division: a mycobacterial perspective. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:126–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00028-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hameed S., Pal R., Fatima Z. Iron acquisition mechanisms: promising target against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Open Microbiol J. 2015;31:91–97. doi: 10.2174/1874285801509010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal R., Hameed S., Fatima Z. Iron deprivation affects drug susceptibilities of mycobacteria targeting membrane integrity. J Pathog. 2015;2015:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2015/938523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C., Lorenz W.W., Hoopes J.T., Dean J.F. Oxidation of phenolate siderophores by the multicopper oxidase encoded by the Escherichia coli yacK gene. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4866–4875. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4866-4875.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamet S., Slama N., Domingues J., et al. The non-essential mycolic acid biosynthesis genes hada and hadc contribute to the physiology and fitness of Mycobacterium smegmatis. PLoS One. 2015;10:2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folch J., Lees M., Stanley S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissue. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pal R., Hameed S., Kumar P., Singh S., Fatima F. Comparative lipidome profile of sensitive and resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2015;(Special Issue 1):189–197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S., Pal R., Hameed S., Fatima Z. Antimycobacterial mechanism of vanillin involves disruption of cell surface intensity, virulence attribute and iron homeostasis. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cravioto A., Gross R.J., Scotland S.M., et al. An adhesive factor found in strains of Escherichia coli belonging to the traditional infantile enteropathogenic serotypes. Curr Microbiol. 1979;3:95. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsugit S., Guma S., Pillay B., et al. Pili contribute to biofilm formation in vitro in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoe. 2013;104:725–735. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashiru O.T., Pillay M., Sturm A.W. Adhesion to and invasion of pulmonary epithelial cells by the F15/LAM4/KZN and Beijing strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:528–533. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.016006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdulla A.A., Abed T.A., Saeed A.M. Adhesion, autoaggregation and hydrophobicity of six Lactobacillus strains. Br Microbiol Res J. 2014;4:381–391. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta K.R., Kasetty S., Chatterji D. Novel functions of (p)ppGpp and cyclic di-GMP in mycobacterial physiology revealed by phenotype microarray analysis of wild-type and isogenic strains of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:2571–2578. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03999-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ojha A., Hatfull G.F. The role of iron in Mycobacterium smegmatis biofilm formation: the exochelin siderophore is essential in limiting iron conditions for biofilm formation but not for planktonic growth. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:468–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busscher H., Weerkamp A. Specific and non-specific interactions in bacterial adhesion to solid substrata. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamed N., Teeters M., Patti J., Hook M., Ross J. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus adherence to collagen under dynamic conditions. Infect Immun. 1999;67:589–594. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.589-594.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunne W., Jr. Bacterial adhesion: seen any good biofilms lately? Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;15:155–166. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.155-166.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abidi S.H., Ahmed K., Sherwani S.K., Bibi N., Kazmi S.U. Detection of Mycobacterium smegmatis biofilm and its control by natural agents. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3:801–812. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendinger B., Rijnaarts H.H.M., Altendorf K., Zehnder A.J.B. Physiochemical cell surface and adhesive properties of coryneforms bacteria related to the presence and chain length of mycolic acids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3973–3977. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3973-3977.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]