Abstract

Background

The infectious diseases specialist is a medical doctor dedicated to the management of infectious diseases in their individual and collective dimensions.

Objectives

The aim of this paper was to evaluate the current profile and distribution of infectious diseases specialists in Brazil.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study using secondary data obtained from institutions that register medical specialists in Brazil. Variables of interest included gender, age, type of medical school (public or private) the specialist graduated from, time since finishing residency training in infectious diseases, and the interval between M.D. graduation and residency completion. Maps are used to study the geographical distribution of infectious diseases specialists.

Results

A total of 3229 infectious diseases specialist registries were counted, with 94.3% (3045) of individual counts (heads) represented by primary registries. The mean age was 43.3 years (SD 10.5), and a higher proportion of females was observed (57%; 95% CI 55.3–58.8). Most Brazilian infectious diseases specialists (58.5%) practice in the Southeastern region. However, when distribution rates were calculated, several states exhibited high concentration of infectious diseases specialists, when compared to the national rate (16.06). Interestingly, among specialists working in the Northeastern region, those trained locally had completed their residency programs more recently (8.7 yrs; 95% CI 7.9–9.5) than physicians trained elsewhere in the country (13.6 yrs: 95% CI 11.8–15.5).

Conclusion

Our study shows that Brazilian infectious diseases specialists are predominantly young and female doctors. Most have concluded a medical residency training program. The absolute majority practice in the Southeastern region. However, some states from the Northern, Northeastern and Southeastern regions exhibit specialist rates above the national average. In these areas, nonetheless, there is a strong concentration of infectious diseases specialists in state capitals and in metropolitan areas.

Keywords: Communicable diseases, Infectious disease medicine, Specialization, Internship and residency, Brazil

Introduction

The infectious diseases specialty is a medical professional field dedicated to the management of disease in both individual and collective dimensions. The infectious diseases specialist (ID) must thus have comprehensive medical knowledge and skills to be able to integrate individual clinical data with concepts that emerge from other biomedical areas that include epidemiology, microbiology, immunology, and public health. To provide comprehensive care to patients suffering with bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections, an ID should not only be able to diagnose and treat the patient properly, but also to participate in the surveillance and prevention of communicable diseases spread. Moreover, IDs may also play an expert role in assessing the ecological and economic impact of infectious diseases on health systems and the community. Currently, Brazilian IDs require versatile attributes in order to face patient care related to endemic neglected tropical diseases, HIV/AIDS, and viral hepatitis, as well as novel health challenges, such as emerging and reemerging diseases (H1N1 influenza, chikungunya, and Zika viral infections), multi-resistant bacterial infections and hospital infection control, infections in migrants, travelers and in immunocompromised patients.1, 2, 3

Brazilian ID training started with the implementation of a specialized medical residency program in 1952 at Hospital das Clinicas, affiliated to the University of São Paulo Faculty of Medicine.4, 5 Since then, new programs were launched in other regions, before national regulations were established in 1977 under the Federal Decree number 80,281,6 which created the Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica – CNMR (National Medical Residency Committee), affiliated to the Ministry of Education. In 1981, Federal Law number 6,9327, 8 was passed and conceptualized residency training as the recommended “post-graduation program for medical doctors, based on in-service training under the supervision of ethical and highly skilled medical professionals”. Finally, minimum curricula requirements for these training programs were approved and implemented nationwide in 1983.9

Currently, certification of ID in Brazil is obtained after completing a 3-year infectious disease residency training (IDRT) at a CNRM-accredited institution.10, 11 MR programs include learning activities in several practice scenarios, such as outpatient clinics, hospital inpatient wards, intensive care units and field work, covering aspects related to internal medicine and infectious diseases. Each program may place special emphasis on diseases that are more prevalent in its location.12 Alternatively, ID may be certified after approval in a board examination, prepared by the Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia – SBI (Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases) and accredited by the Associação Médica Brasileira – AMB (Brazilian Medical Association).10, 11, 13

Infectious disease specialists have an important role to play in medical care provision in Brazil. It is broadly recognized that the country has experienced an irregular epidemiological transition.14, 15 Although infectious diseases-related deaths have been remarkably reduced over the past six decades, these illnesses still remain relevant public health issues. Despite having successfully controlled vaccine-preventable diseases, cholera, and vector-borne Chagas’ disease, some illnesses remain for which control has failed (i.e., dengue and visceral leishmaniasis) or been partially effective (i.e., HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, leprosy, tuberculosis, and schistosomiasis), due to complex transmission patterns associated with adverse environmental, social, economic, or unknown determinants. Moreover, some of these diseases are chronic, exhibit long infective periods and require prolonged treatment, or sometimes are transmitted by insect vectors that are difficult to control.16

When planning healthcare strategies for the Brazilian population, a clear understanding of how specialized healthcare personnel is prepared to face these challenges and to what extent these professionals are available throughout the country is certainly useful. The aim of this paper is thus to evaluate the current profile and distribution of IDs in Brazil.

Material and methods

This is a cross-sectional study using secondary data. Evaluated datasets included administrative registry and notary data obtained after linkage of three primary sources: Conselho Federal de Medicina – CFM (Federal Medical Council) database that integrated information from 27 Conselhos Regionais de Medicina – CRMs (Regional Medical Councils), including one database from each Brazilian state; the database of the Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica – CNMR (National Medical Residency Committee), affiliated to the Ministry of Education; and the Associação Médica Brasileira – AMB (Brazilian Medical Association) dataset that integrated databases from medical specialty societies (BSID, in this case). All databases were accessed in May 2014.

An ID was defined as a physician who completed IDRT in a CNRM-accredited program or who had passed the BSID board examination.10, 11

Qualitative variables of interest for our study included gender, age, type of medical school the ID graduated from (public or private), time since completion of IDRT, interval between medical graduation and IDRT completion, and the Brazilian region where the IDRT took place. Time since completion of the IDRT was also evaluated quantitatively.

Relative distribution of IDs was computed as follows: (number of ID/total population) × 1,000,000 inhabitants.

ID distribution was assessed in two ways: state affiliation according to the corresponding state CRM registry and municipal affiliation based on the mailing address provided by the physician to the CRM. The Brazilian region where the physician completed his/her medical residency program was used as a stratifying variable.

Population data were obtained from Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics).17 Comparison between the profile and distribution of IDs and other specialist physicians (OS) was possible due to access to the Brazilian Medical Demography study database.18

Proportions and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used as descriptive statistics. Selected variables were then studied in conjunction with CIs estimated in 1000 bootstrapped samples.19 A computational software, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences – SPSS 20 for Windows (International Business Machines Corp., New York, USA), was used for statistical analysis.

Mailing addresses were used to generate the dot density map. The municipality was adopted as the geographic unit of analysis, and one dot represents one ID. The state was used as the unit of analysis for the color map, with darker tones representing higher ID densities. Maps were generated using Quantum GIS (version 1.7.4; QGIS Development Team – http://www.qgis.org/en/site/).

Results

A total of 3229 ID registries were analyzed, with 94.3% (3045) of the individual counts (head) obtained from primary registries and 5.7% (184) from secondary registries. Individual data are evaluated based on the number of heads and geographical distribution with the total number of registries.

Descriptive analyses of the ID profile are provided in Table 1. The gender distribution of IDs was heterogeneous, with a higher proportion of females in the sample. The mean age was 43.3 years (SD 10.5); with predominance of the younger categories, especially ages between 30–34 and 35–39. These features were significantly different from the distribution of other medical specialists (OS).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of Brazilian infectious diseases specialists, 2015.

| ID (n) | ID (%) | 95% CI |

OS Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1737 | 57.0 | 55.3 | 58.8 | 40.5 |

| Male | 1308 | 43.0 | 41.2 | 44.7 | 59.9 |

| Total | 3045 | 100 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤29 | 126 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 2.4 |

| 30–34 | 631 | 20.7 | 19.1 | 22.2 | 14.8 |

| 35–39 | 607 | 19.9 | 18.5 | 21.4 | 15.5 |

| 40–44 | 444 | 14.6 | 13.3 | 15.9 | 13.1 |

| 45–49 | 357 | 11.7 | 10.6 | 12.9 | 12.7 |

| 50–54 | 365 | 12.0 | 10.8 | 13.2 | 11.5 |

| 55–59 | 271 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 9.9 | 11.1 |

| 60–64 | 137 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 9.6 |

| 65–69 | 63 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 4.9 |

| ≥70 | 44 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 4.4 |

| Total | 3045 | 100 | |||

| Type of medical school IDs graduated froma | |||||

| Public | 2017 | 71.6 | 70.0 | 73.3 | |

| Private | 799 | 28.4 | 26.7 | 30.0 | |

| Total | 2816 | 100 | |||

| Medical residency training in ID | |||||

| No | 579 | 19.0 | 17.7 | 20.3 | |

| Yes | 2466 | 81.0 | 79.7 | 82.3 | |

| Total | 3045 | 100 | |||

| Interval between M.D. graduation and completion of residency training (years) | |||||

| ≤3 | 555 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 26.1 | |

| 4–10 | 1629 | 66.1 | 69.3 | 73.3 | |

| ≥10 | 282 | 11.4 | 7.6 | 15.3 | |

| Total | 2466 | 100 | |||

| Brazilian Region where residency training was completed | |||||

| Northern | 128 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 6.0 | |

| Northeastern | 301 | 12.2 | 10.9 | 13.5 | |

| Southeastern | 1746 | 70.8 | 68.9 | 72.5 | |

| Southern | 174 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 8.1 | |

| Center-western | 117 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 5.6 | |

| Total | 2466 | 100 | |||

| Time since completion of residency training (years) | |||||

| <2 | 395 | 16.0 | 14.7 | 17.6 | |

| 2–5 | 438 | 17.8 | 16.2 | 19.2 | |

| 5–10 | 569 | 23.1 | 21.3 | 24.7 | |

| ≥10 | 1064 | 43.1 | 41.1 | 45.1 | |

| Total | 2466 | 100 | |||

M.D.G., MD graduation; OS, other specialist medical doctors; ID, infectious diseases specialists; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Missing data = 229.

We also observed that 71.6% of IDs had graduated in Medicine from public higher education institutions, and that 81% of them had concluded a medical residency program in the field. Over 70% completed their ID residency training in the Southeast region of Brazil, and 43.1% had concluded it more than 10 years before (Table 1). Table 2 shows other medical specialties simultaneously practiced by IDs.

Table 2.

Other medical specialties practiced by Brazilian infectious diseases specialists, 2015.

| Specialties | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 339 | 34.1 |

| Pediatrics | 260 | 26.1 |

| Intensive care | 74 | 7.4 |

| Occupational medicine | 63 | 6.3 |

| Preventive and social medicine | 28 | 2.8 |

| Family and community medicine | 26 | 2.6 |

| Acupuncture | 25 | 2.5 |

| Dermatology | 23 | 2.3 |

| Pathology | 15 | 1.5 |

| Cardiology | 14 | 1.4 |

| Laboratory medicine | 13 | 1.3 |

| Traffic medicine | 11 | 1.1 |

| Pneumology | 11 | 1.1 |

| General surgery | 9 | 0.9 |

| Othersa | 84 | 8.4 |

| Total | 995 | 100.0 |

Including 25 specialties practiced by infectious diseases specialists.

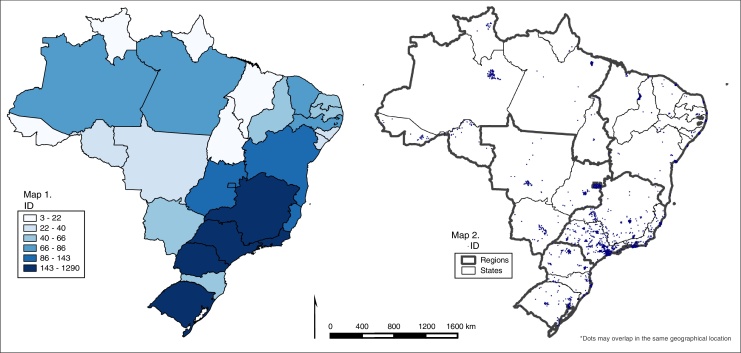

The absolute distribution of IDs, according to the Brazilian administrative regions and states is evaluated in Table 3, Table 4. The Southeastern region showed the highest proportion of IDs (58.5%), followed by the Northeastern (16.1%) and Southern regions (10.7%). States with the lowest absolute number of IDs (less than 22 IDs) were Acre, Roraima, Amapá, Tocantins, and Maranhão. In contrast, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná, and Rio Grande do Sul had more than 143 IDs (Fig. 1 – Map 1). It is important to highlight that states with higher numbers of IDs also showed some dispersion of dots within the state (Fig. 1 – Map 2). In Table 4 we describe the relative distribution of IDs by state populations.

Table 3.

Distribution of infectious diseases specialists and other specialist medical doctors according to Brazilian regions, 2015.

| Region | ID (n) | ID (%) | 95% CI |

OS (%)16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Northern | 208 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 3.5 |

| Northeastern | 522 | 16.2 | 14.9 | 17.5 | 15.4 |

| Southeastern | 1891 | 58.5 | 56.8 | 60.4 | 54.4 |

| Southern | 348 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 11.9 | 18.2 |

| Center-western | 260 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 8.5 |

| Total | 3229 | 100 | 100 | ||

ID, infectious diseases specialists; OS, other specialist medical doctors; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 4.

Density of infectious diseases specialists according to Brazilian states, 2015.

| State/region | n | Inhabitants17 | ID densitya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rondônia | 22 | 1,728,214 | 12.73 |

| Acre | 19 | 776,463 | 24.47 |

| Amazonas | 65 | 3,807,921 | 17.07 |

| Roraima | 14 | 488,072 | 28.68 |

| Para | 75 | 7,969,654 | 9.41 |

| Amapá | 3 | 734,996 | 4.08 |

| Tocantins | 10 | 1,478,164 | 6.77 |

| Northern | 208 | 16,983,484 | 12.25 |

| Maranhão | 18 | 6,794,301 | 2.65 |

| Piauí | 49 | 3,184,166 | 15.39 |

| Ceara | 70 | 8,778,576 | 7.97 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 58 | 3,373,959 | 17.19 |

| Paraíba | 55 | 3,914,421 | 14.05 |

| Pernambuco | 80 | 9,208,550 | 8.69 |

| Alagoas | 38 | 3,300,935 | 11.51 |

| Sergipe | 35 | 2,195,662 | 15.94 |

| Bahia | 119 | 15,044,137 | 7.91 |

| Northeastern | 522 | 55,794,707 | 9.36 |

| Minas Gerais | 249 | 20,593,356 | 12.09 |

| Espirito Santo | 89 | 3,839,366 | 23.18 |

| Rio De Janeiro | 392 | 16,369,179 | 23.95 |

| São Paulo | 1161 | 43,663,669 | 26.59 |

| Southeastern | 1891 | 84,465,570 | 22.39 |

| Paraná | 134 | 10,997,465 | 12.18 |

| Santa Catarina | 74 | 6,634,254 | 11.15 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 140 | 11,164,043 | 12.54 |

| Southern | 348 | 28,795,762 | 12.09 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 41 | 2,587,269 | 15.85 |

| Mato Grosso | 34 | 3,182,113 | 10.68 |

| Goiás | 94 | 6,434,048 | 14.61 |

| Distrito Federal | 91 | 2,789,761 | 32.62 |

| Center-western | 260 | 14,993,191 | 17.34 |

| Brazil | 3229 | 201,032,714 | 16.06 |

Infectious diseases specialist density per million inhabitants.

Fig. 1.

(Map 1) Absolute distribution of infectious diseases specialists according to Brazilian states, 2015. (Map 2) Dot density of absolute distribution of infectious diseases specialists by Brazilian municipalities according to Brazilian regions, 2015.

The overall mean time since completion of medical residency training (RCt) was 10.9 years (SD 8.5). Similar RCts were observed among IDs from the Southeastern region, regardless whether they had been trained locally (δ) or elsewhere in Brazil (†). In contrast, significant differences were noted in the Northeastern regions for δ – 8.7 years (95% CI 7.9–9.5) vs † – 13.6 years (95% CI 11.8–15.5), and less remarkably in the Northern region 8.4 years (95% CI 7.1–9.9) for δ vs 11.8 years (95% CI 9.6–14.3) for †(Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean time after completion of medical residency training among infectious diseases specialists according to Brazilian regions, 2015.

| Region | Residency | ID (n) | ID (%) | RCt (mean) | RCt 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Lower | |||||

| Northern | δ | 30 | 21.0 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 9.9 |

| † | 113 | 79.0 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 14.3 | |

| Total | 143 | 100 | ||||

| Northeastern | δ | 78 | 22.3 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 9.5 |

| † | 272 | 77.7 | 13.6 | 11.8 | 15.5 | |

| Total | 350 | 100 | ||||

| Southeastern | δ | 1524 | 97.4 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 12.2 |

| † | 40 | 2.6 | 14.8 | 10.0 | 17.4 | |

| Total | 1564 | 100 | ||||

| Southern | δ | 83 | 35.2 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 10.5 |

| † | 153 | 64.8 | 11.5 | 9.7 | 13.2 | |

| Total | 236 | 100 | ||||

| Center-western | δ | 67 | 38.7 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 11.2 |

| † | 106 | 61.3 | 9.7 | 7.7 | 11.6 | |

| Total | 173 | 100 | ||||

| Total | 2466 | |||||

δ, physicians living in the same region where specialty training was completed; †, physicians living in a different region from where specialty training was completed; RCt, time since residency completion (years), ID, infectious diseases specialists; OS, other specialist medical doctors; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ID, infectious disease specialist.

Discussion

The specialist physician is considered a very important professional for healthcare provision. Many studies have shown that specialists are more knowledgeable than general practitioners concerning the proper use of diagnostic techniques and efficacious therapies to provide care deemed appropriate.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Currently, Brazil has a total of 405,744 physicians (head).26 Out of this total, medical specialties account for 207,879 physicians.18 Thus, we can infer that the number of infectious diseases specialists is low, as compared to the number of total physicians (0.75%) or to the total number of medical specialists (1.46%). In Brazil, specialties that congregate the largest number of physicians are pediatrics, gynecology and obstetrics, general surgery, internal medicine, anesthesiology, occupational medicine, and cardiology, which together account for 52.9% of all specialists. It is noteworthy that 28.8% (879) of all 3045 IDs also practiced another medical specialty (Table 2). In total, 995 specialties are practiced by these 879 IDs, as some referred up to four specialties. The most common simultaneously practiced specialties were internal medicine (34.1%) and pediatrics (26.1%). This could be due to the fact that, since 2003, one year of training in internal medicine is a required component of IDRT; and because pediatric infectious disease is a commonly sought subspecialty by both IDs and pediatricians.

Statistics concerning the worldwide ID distribution are scarce. In Europe, countries where the specialty seems to be more represented are Turkey (1433, head), Romania (400, head), and Hungary (350, head). In relative terms (IDs per million inhabitants), Iceland (47), Hungary (35) Sweden (34), Latvia (31), and Croatia (30) are the most representative.27 In international comparative standards, Brazil has 16.6 ID per million inhabitants, similarly to Switzerland, Norway, and Romania; even though the epidemiological relevance of infectious diseases differs among these countries. In the United State of America (USA), a survey with physicians who prescribe antiretroviral therapy (PPAT) and their patients showed that 40% and 42% had been formally trained in infectious diseases.25 In Brazil, a similar study conducted in São Paulo showed that 51.2% of PPAT were formally trained IDs; if IDs who were formally certified by the BSID were added, 67.2% of Brazilian PPAR fell into this category.28

Our study also highlights that the absolute and relative distributions of ID are heterogeneous among Brazilian regions. The Southeastern region concentrated more than half of all ID records (58.8%). Interestingly, when the ID distribution was compared with other specialist physicians (OS) frequencies, the Northern and Southern regions drew special attention: the proportion of IDs in the Amazon exceeded that of other specialists – 6.4% (95% CI 5.5–7.2%) vs OS 3.5%, but the opposite feature was seen in the Southern region – 10.8% of IDs (95% CI 9.7–11.9%) vs 18.1% of OS.

Brazilian states with the largest ID densities were Acre (24.4/1 million inhabitants), Roraima (28.6), Amazonas (17.0) [Northern region], Rio Grande do Norte (17.1) [Northeast], São Paulo (26.5), Rio De Janeiro (23.9), Espírito Santo (23.1) [Southeastern], and Distrito Federal (32.6) [Mid-Western region] (Table 4). This assessment allows us to identify two distinct clusters. The Southeastern region is recognized as the Brazilian epicenter for specialty medical training, since it concentrated 66.7% of all vacancies in MR programs and 51.3% (97) in IDRT programs in 2011,29 mainly in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. This region also has the largest population and therefore more demands for specialized healthcare centers and higher numbers of general practitioners and specialists.2, 18 The Northern region, in contrast, exhibits a peculiar epidemiological profile, with high demand for care in tropical infectious diseases, such as malaria, leprosy, typhoid fever, and leishmaniasis, in addition to AIDS, tuberculosis, and viral hepatitis that occur throughout Brazil.3, 16 Infectious diseases are also an important cause of lost years of life in Brazil as a whole, with a greater proportion of infection-related deaths occurring in the North and Northeast.14

Two heterogeneous patterns in the distribution of Brazilian IDs can be identified on the presented maps (Fig. 1). When adjusted for the state population (Table 3), the ID distribution was noticeably different among states [Map 1], but also differed within a given state [Map 2]. Dots usually cluster around state capitals and/or in metropolitan areas, even in states where a more homogeneous distribution of ID is noticed (São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and Paraná). This finding suggests that even in states where the estimated ID rates are higher, the availability of IDs in the countryside may not be sufficient.

An important issue to be considered in medical education is whether specialist training centers are able to provide professionals to meet the region's healthcare needs. In this context, we observed that IDs from the Northeastern region who completed their training locally showed a significant lower time since residency completion (RCt), as compared to those trained in other Brazilian regions. In addition, locally trained specialists are still the minority of IDs (22.3%) in this region. We believe these data can indicate temporal changes in professional allocation. Local institutions are recently training more specialists who get settled in the same region where the IDRT took place. We should consider this as promising, since such specialists are supposed to have experienced clinical challenges during their training that are more likely to be found in the location they have chosen for their professional practice.

Our study also found that most Brazilian IDs specialists concluded a medical residency program (81%; 95% CI 79.7–82.3%). The time gap between their graduation and certification as specialists was in average 4.8 years (SD 3.4 years). In fact, 66.1% (95% CI 69.3–73.3) concluded training between 4 and 10 years after graduation. If we take into account that 33.8% of IDs concluded their training in less than 5 years after graduating in Medicine we can have an idea of the number of ID we will have in the next 5 years, in case this rate of formation is maintained.

An interesting finding in our study was the higher proportion of females in infectious diseases practice (57%). This fact could be explained by a higher proportion of young physicians among the IDs, 44.7% of them aged less than 39. In 2013, data analyzed by the Brazilian Medical Demography study18 noted that infectious diseases was the seventh specialty with more women, following hematology (56.8%), allergy and immunology (60.8%), endocrinology (65%), medical genetics (66.5%), pediatrics (69.6%), and dermatology (72.9%), and the third youngest medical specialist body (mean age 43.3 – SD 10.1), following family and community medicine (41.3 – SD 9.04) and internal medicine (40.6 – SD 9.77). We thus suggest that even though ID are not many in the country, the specialty is more frequently being chosen by recent graduates. In addition, feminization of medicine in Brazil is a consistent trend that has been observed over the past decade and recently emphasized.18, 30 The growth in female participation is evident if we take the number of women trained every year who are entering the job market, based on national data pooled from new CRM records.31The increased participation of women in the medical profession is not a recent phenomenon and has not only occurred in Brazil. The proportion of females among physicians from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) grew between 1990 and 2005 from 28.7% to 38.3% of physicians.32 In the early 2000s, women were already the majority among American and Canadian medical students,33, 34 and in the 1990s, medical undergraduate courses already had a female majority in several countries, including England,35 Ireland,36 and Norway.37 Further studies are warranted to explain more deeply the factors associated with an increased participation of women in medical practice and, in particular, in infectious diseases care.

The main strength of our study relies on the linkage of strongly robust databases (CFM, CNMR and AMB), containing documented information about specialists in Brazil. Even though information was originally collected for administrative proposes, data analysis enables thoughtful insights. Limitations related to use of secondary data have, nevertheless, to be taken into account. Double registrations, though limited to 5.7% of the sample, were due to the fact that few physicians practiced in more than one state.

In conclusion, we believe our study provides useful information for medical education in Brazil, particularly related to the medical specialty training in infectious diseases provided by academic institutions, and their ultimate impact in specialized healthcare provision. We encourage further studies to consider ID national distribution and its correlation with the burden of infectious diseases that differs among Brazilian regions.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Amato Neto V. Infectologia velha e infectologia nova: concepção extravagante. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004;37:510–511. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822004000600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrak R.M., Sexton D.J., Butera M.L., et al. The value of infectious disease specialist. Clin Infec Dis. 2003;36:1013–1017. doi: 10.1086/374245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Referentiel-metier_infectiologie. Collège des Universitaires de Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales (CMIT) et Conseil National des Universités (CNU) Sous-section 45/03. Available from http://www.infectiologie.com/site/medias/positions/Referentiel-metier_infectiologie-2011.pdf [accessed 20.06.15].

- 4.Sampaio S.A.P. FUNDAP; São Paulo: 1984. Residência Médica no Hospital das Clínicas: 40 anos de história. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foccacia R., Neto V.A., Elias P.E.M. Residência Médica em Doenças Infecciosas e Parasitárias no Hospital das Clínicas da F.M.U.S.P. Rev Hosp Clín Fac Med S Paulo. 1988;43:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 1977. Brasil Decreto Presidencial n°. 80.281, de 5 de setembro de 1977. Regulamenta a Residência Médica, cria a Comissão Nacional de residência Médica e dá outras providências. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1970-1979/D80281.htm [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 1981. Brasil Lei n°. 6.932, de 7 de julho de 1981. Dispõe sobre as atividades do médico residente, e dá outras providências. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/CCIVIL_03/Leis/L6932.htm [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasil. Resolução CNRM 01/81 . Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 1981. Estabelece especialidades médicas credenciáveis como Programa de Residência Médica e dá providências adicionais. Available from: http://portal.mec.gov.br/sesu/arquivos/pdf/CNRM0181.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brasil. Resolução CNRM 04/83 . Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 1981. Dispõe sobre os requisitos mínimos dos programas de Residência Médica das especialidades médicas e dá outras providências. Available from: http://portal.mec.gov.br/sesu/arquivos/pdf/CNRM0483.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brasil Resolução CFM n° 1634/2002 . Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 2002. Dispõe sobre convênio de reconhecimento de especialidades médicas firmado entre o Conselho Federal de Medicina CFM, a Associação Médica Brasileira – AMB e a Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica – CNRM. Available from: http://www.portalmedico.org.br/resolucoes/CFM/2002/1634_2002.htm [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil Resolução CFM N° 2.116/2015 . Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 2015. Dispõe sobre a nova redação do Anexo II da Resolução CFM n° 2.068/2013, que celebra o convênio de reconhecimento de especialidades médicas firmado entre o Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM), a Associação Médica Brasileira (AMB) e a Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica (CNRM) Available from: http://www.portalmedico.org.br/resolucoes/CFM/2015/2116_2015.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia . 2005. Livro 25 anos SBI.SBI: consolidação da infectologia no Brasil. Available from: http://itarget.com.br/newclients/sbi/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/livro01.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia . 2015. Concurso para título de especialista em infectologia. Available from: http://infecto2015.com.br/Edital_prova_titulo_sbi2015.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schramm J.M.A., Oliveira A.F., Leite I.C., et al. Transição epidemiológica e o estudo de carga de doença no Brasil. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2004;9:897–908. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luna E.J.A. A emergência das doenças emergentes e as doenças infecciosas emergentes e reemergentes no Brasil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2002;5:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barreto M.L., Teixeira M.G., Bastos F.I., Ximenes R.A., Barata R.B., Rodrigues L.C. Successes and failures in the control of infectious diseases in Brazil: social and environmental context, policies, interventions, and research needs. Lancet. 2011;377:1877–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60202-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Estimativas populacionais para os municípios brasileiros em 01.07.2013. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/estimativa_2013_dou.pdf [accessed 20.02.15].

- 18.Scheffer M, Biancarelli A, Cassenote A. Demografia Médica no Brasil: cenários e indicadores de distribuição. Conselho Regional de Medicina do Estado de São Paulo e Conselho Federal de Medicina, 117. Available from: http://www.cremesp.org.br/pdfs/DemografiaMedicaBrasil Vol2.pdf [accessed 20.02.15].

- 19.Efron B., Tibshirani R.J. Chapman & Hall/CRC; New York: 1993. An introduction to the bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan N.C., Martin G.J., Robinson J.K., Rademaker A.W. Skin cancer control practices among physicians in a university general medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:515–519. doi: 10.1007/BF02602405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin M.H., Friedmann P.D., Cassel C.K., Lang R.M. Differences in generalist and specialist physicians’ knowledge and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for congestive heart failure. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:523–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber T.L., Elkhatib A., Grines C.L., O’Neill W.W. Cardiologist versus internist management of patients with unstable angina: treatment patterns and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00214-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vickrey B.G., Edmonds Z.V., Shatin D., et al. General neurologist and subspecialist care for multiple sclerosis: patients’ perceptions. Neurology. 1999;53:1190–1197. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norquist G., Wells K.B., Rogers W.H., Davis L.M., Kahn K., Brook R. Quality of care for depressed elderly patients hospitalized in the specialty psychiatric units or general medical wards. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:695–701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950200085018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landon B.E., Wilson I.B., Cohn S.E., et al. Physician specialization and antiretroviral therapy for HIV: adoption and use in a national probability sample of persons infected with HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:233–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conselho Federal de Medicina . CFM; 2015. Estatística. Available from: http://portal.cfm.org.br/index.php?option=com_estatistica [accessed 20.02.15] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Read R.C., Cornaglia G., Kahlmeter G., et al. Professional challenges and opportunities in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;1:408–415. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheffer M.C., Escuder M.M., Grangeiro A., Castilho E.A. Formação e experiência profissional dos médicos prescritores de antirretrovirais no Estado de São Paulo. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56:691–696. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaves H.L., Borges L.B., Guimarães D.C., Cavalcanti L.P.G. Vagas para residência médica no Brasil: Onde estão e o que é avaliado. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2013;37:557–565. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheffer M., Biancarelli A., Cassenote A.J.F. Conselho Federal de Medicina e Conselho Regional de Medicina do Estado de São Paulo; São Paulo, SP: 2011. Demografia médica no Brasil. Dados gerais e descrições de desigualdades. Relatório de pesquisa. Available from: http://www.cremesp.org.br/pdfs/demografia_2_dezembro.pdf [accessed 20.06.15] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheffer M.C., Cassenote A.J.F. A feminização da medicina no Brasil. Rev Bioét. 2013;21:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development . OECD; 2009. OECD health data 2009: comparing health statistics across OECD countries. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/document/57/0,3746,en_21571361_44315115_43220022_1_1_1_1,00.html [accessed 22.04.15] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonasson O. Leaders in American surgery: where are the women? Surgery. 2002;131:672–675. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beagan B.L. Neutralizing differences: producing neutral doctors for (almost) neutral patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1253–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McManus I.C., Sproston K.A. Women in hospital medicine in the United Kingdom: glass ceiling, preference, prejudice or cohort effect. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:10–16. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonough C.M., Horgan A., Codd M.B., Casey P.R. Gender differences in the results of the final medical examination at University College Dublin. Med Educ. 2000;34:30–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kvaerner K.J., Aasland O.G., Botten G.S. Female medical leadership: cross sectional study. BMJ. 1999;318:91–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7176.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]