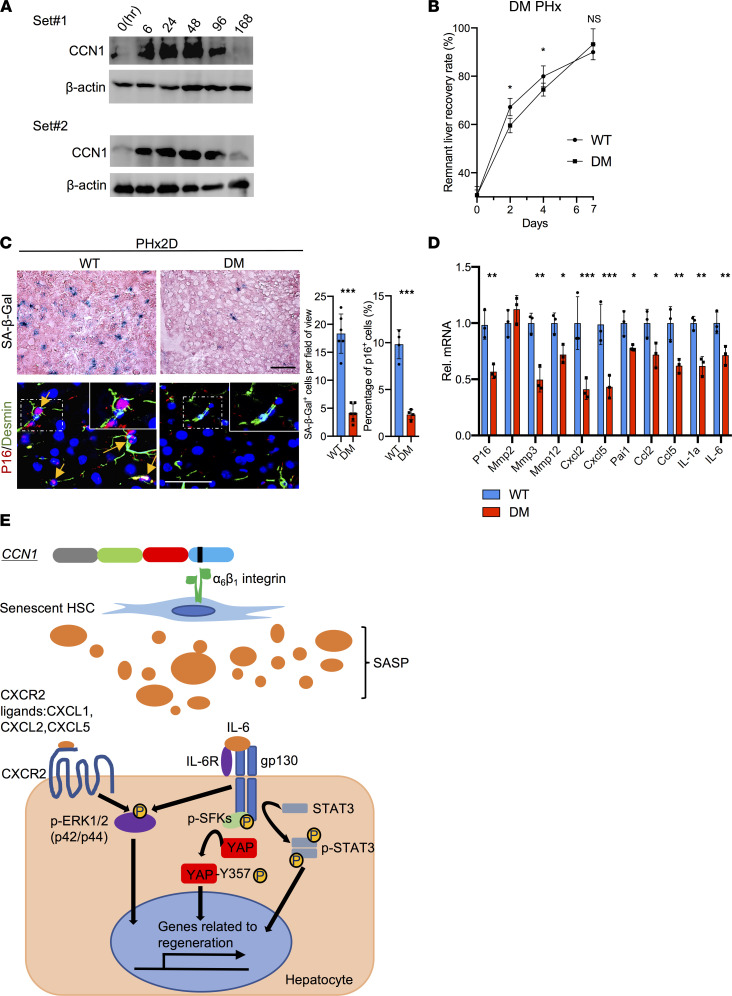

Figure 6. CCN1 induces senescence in HSCs and contributes to liver regeneration.

(A) Liver protein extracts from WT mice at the indicated times (hours) after PHx were immunoblotted and probed with anti-CCN1 and anti–β-actin antibodies. (B) The remnant liver recovery rates were assessed for WT and Ccn1DM/DM (DM) mice at indicated times after PHx (day 0, n = 3; day 2 and 7, n = 4; day 4, n = 8). (C) SA-β-Gal staining of frozen liver sections from WT and DM mice 2 days after PHx. Liver sections were also double immunostained for p16 (red) and desmin (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Yellow arrowheads are pointing to p16+ cells. The number of SA-β-Gal+ cells (n = 6) per microscopic field and percentage of p16+ cells (n = 4) were quantified by cell counting. (D) Expression of genes related to cell cycle arrest and the SASP in WT and Ccn1DM/DM mouse livers 2 days after PHx was measured by qRT-PCR (n = 3). (E) Schematic diagram illustrating proposed SASP signaling pathways contributing to liver regeneration. The matricellular protein CCN1 is released upon injury and induces cellular senescence in HSCs through integrin α6β1 within 2 days after PHx. Senescent cells secrete proteins of the SASP critical to liver regeneration, including IL-6, which engages IL-6R and gp130 to induce hepatocyte proliferation through activation of STAT3 and SFK-mediated phosphorylation of YAP. IL-6 also synergizes with CXCR2 ligands secreted as part of the SASP, including CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5, to induce a robust activation of ERK1/2 that promotes hepatocyte proliferation. Scale bars: 50 μm. Data expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.033, **P < 0.002, ***P < 0.001 assessed by Student’s t test (C and D) or 2-way ANOVA (B).