Introduction

In 1999, researchers introduced a Black race coefficient of 1.21 to the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) on the basis of the observation that participants who self-identified as Black had a 21% higher measured GFR after controlling for age, sex, and serum creatinine than those who did not self-identify as Black. Use of this coefficient mitigated underestimation bias among Black individuals and overestimation bias among non-Black individuals in the study population, but did not consider confounding from socioeconomic and structural factors, problematic views of race as biology, or potential implications of race-based differential treatment. The subsequent 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation similarly derived a Black race coefficient of 1.16. In 2021, the recommendation by the joint National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Task Force to adopt calculations of eGFR without race sent waves through the medical community (1). Consensus recognition that race-adjusted eGFR causes harm marked a positive and long-needed step forward for nephrology and the greater medical community.

Patients, transdisciplinary experts, and medical trainees contributed in key ways to this movement through grassroots organizing, outreach and education, scientific research and scholarly discourse, and policy and organized medicine. Yet, these perspectives are often excluded or erased from dominant narratives. In this article, writing as trainees ourselves, we recognize the foundational social science and activism upon which the movement to redress race-adjusted eGFR was built, explore motivations for trainee involvement, highlight trainee and patient contributions, and outline next steps to advance equity in kidney care and beyond.

Trainees Made, and Continue to Make, Pivotal Contributions to the Movement for Antiracism in Kidney Care

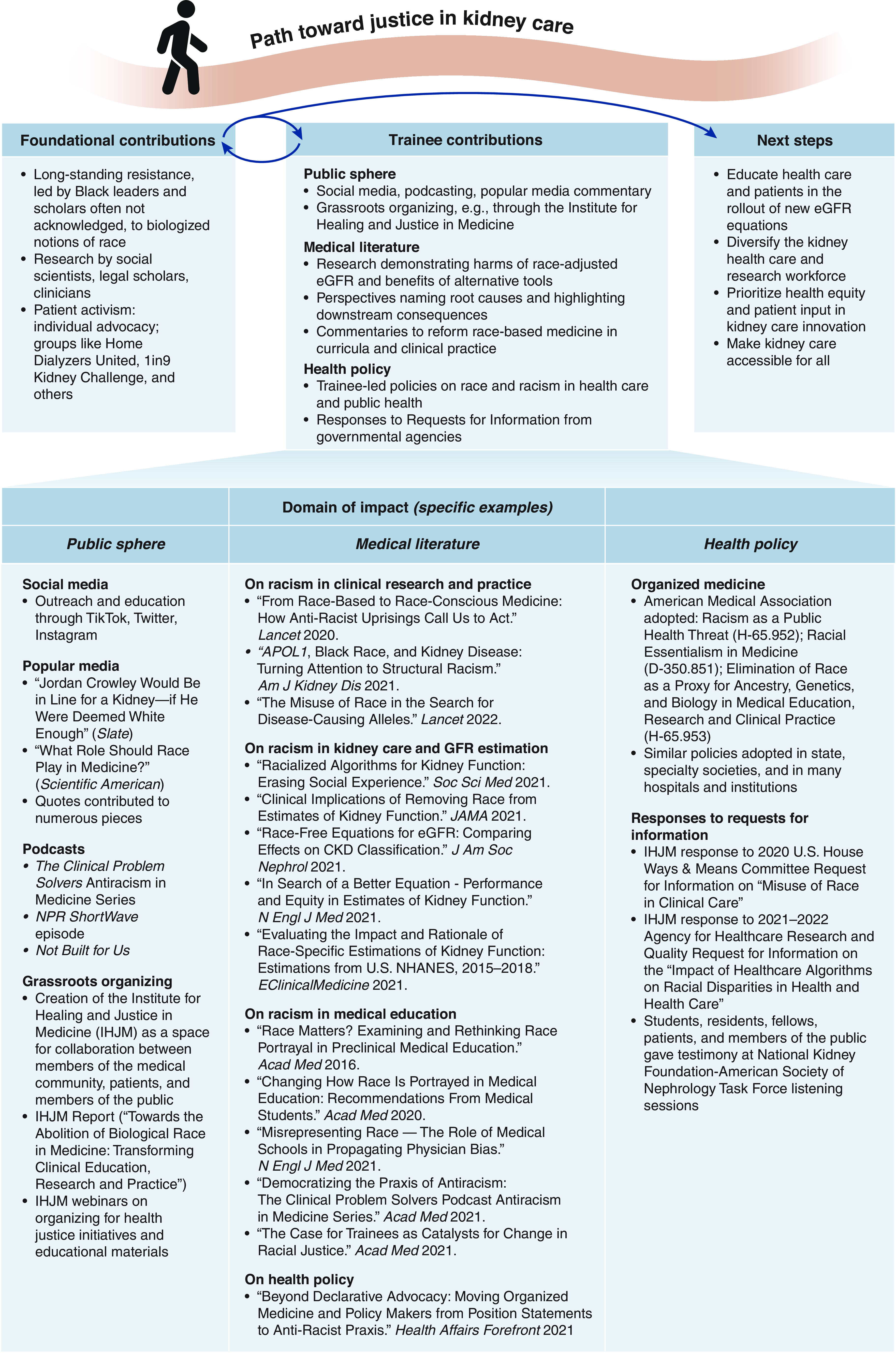

Trainee contributions have been extensive and essential to the current movement to end the misuse of race in medicine, as demonstrated by the specific examples of trainee contributions in Figure 1. We came to this work from a variety of perspectives, often experiencing the health consequences of race-based medicine ourselves or through our family members, friends, communities, and patients. As newcomers to medicine, we perceived a troubling discordance between stated priorities—of equity and rigorous scientific evidence as the basis of clinical decisions—and actual clinical practice. Inadequate explanations, perceptive mentors, and existing antiracist literature propelled us toward advocacy.

Figure 1.

Trainee, patient, and interdisciplinary contributions have been crucial throughout the movement to end the misuse of race in kidney care.

Importantly, the current movement to remove race from eGFR must be contextualized by centuries of relevant work by social scientists and activists. From at least the time of W.E.B. Du Bois at the turn of the twentieth century (2), these individuals emphasized that race is a fluctuating social invention created to reinforce discriminatory hierarchies and called to abolish the use of race as inherent biology. Contemporary scholars such as Dorothy Roberts, Harriet Washington, Ann Morning, Joseph L. Graves Jr., and Lundy Braun published highly influential books and articles investigating the misuse of race in the medical system (3,4). Others, like Debbie Epstein and Troy Duster, described how racism is integrally woven into the fabric of the US social structure. Physicians argued that making medical decisions on the basis of race is institutional racism, regardless of individual intent (5). Geneticists and physical anthropologists showed clinical distributions of human genetic variation are poorly represented by sociopolitical categories like race. This immense, multidisciplinary body of work was instrumental in informing our own efforts. Foundational scholarship and activism, especially by Black leaders, must not be obscured or forgotten in the present wave of equity-oriented discourse, research, and advocacy.

It is similarly vital to acknowledge that patients and trainees joined these endeavors from a place of significant vulnerability. Patients risked anger from care providers for speaking out, and trainees—especially Black trainees—risked retaliation affecting their careers. Nevertheless, patients and trainees took on the work of advocating for change and the resultant clinical and professional consequences. It is worth contemplating how much more readily progress could have been made if medical hierarchies were more willing to listen to the concerns of patients and junior members.

Reforming eGFR Is Necessary but Insufficient to Achieve Equity in Kidney Care

Disparities in kidney care and disease have long contributed to suffering and premature death. Black populations in the United States have higher rates of CKD and kidney failure and have faster disease progression than White people (6,7). Despite this, minoritized patients have worse access to preventive care, early diagnostic testing, timely nephrology referral, chronic disease treatment, high-quality dialysis services, home dialysis, transplant waitlisting, living kidney donation, and transplantation (6,7). These disparities across the kidney care continuum are the result of structural inequities, not limited to the delayed referrals and decreased access to services caused by using race-based eGFR, and they demand continued intervention and accountability. To move beyond symbolic change in nephrology, we recommend the following:

1. Implementation of Race-Free eGFR Must Include Education for Health Care Workers, Trainees, and Patients

Changes in eGFR calculation must be communicated with the full story: why race was brought into kidney function equations, how race was determined and used, the harms of this practice, and the evidentiary basis for its termination. As health systems implement race-free eGFR, they must ensure that Black patients reclassified to more advanced stages of kidney disease receive trustworthy outreach, education, and early referral to appropriate services. Moving forward, health care institutions should clearly outline new metrics that ensure accountability for equitable outcomes. Moreover, contemporary and historical examples of medicine’s active role in establishing and exacerbating racial inequities should be longitudinally integrated throughout medical education, so future generations of health care workers can understand the context of our current health care system and avoid repeating mistakes. Resources for this integration abound (Figure 1).

2. The Kidney Health Care and Research Workforce Should Reflect the Patients We Serve

Relative to the composition of the US population, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people are vastly under-represented in medicine and in nephrology (8). Improving representation within the health care workforce will require a concentrated, sustained effort in developing pathway programs like the Title VII and VIII health professions training programs and the ASN Loan Mitigation Pilot Program.

3. Nephrology Care and Resources Must Be Accessible to All

Kidney disease is heavily affected by structural factors like food insecurity, unaffordability of insulin and other medications, and inadequate access to high-quality health care, all marked by cruel inequities from long-standing racial and economic segregation (6,7). Moreover, current coverage and reimbursement models often provide larger financial incentives for expensive downstream treatment options compared with prevention and early diagnosis. True justice in kidney care requires health care workers and institutions to advocate for and implement interventions that address social and structural determinants of health, equitable access to preventive and primary care, and mechanisms to reduce kidney care costs. Improving social risk adjustment and health equity assessment for kidney care reimbursement models can better align incentives across payors, health systems, clinicians, and marginalized patient populations (9). Advocacy groups, payors, and policy makers should collaborate to ensure costs are not shifted onto patients as new eGFR equations are implemented and demand rises for cystatin C-based testing.

Lessons Learned from Reforming eGFR Should Galvanize Next Steps Within and Beyond Nephrology

As trainees, we consider our professional mission of providing equitable care inextricable from advocacy for political actions to improve patient outcomes. Removal of the Black race modifier from eGFR calculation was a necessary step. However, this change must not lull institutions or policy makers into believing it alone will rectify centuries of institutionalized racism. Removing racialized algorithms without also acknowledging their perils, rebuilding trust, and instituting robust action to address broader inequities in kidney care will waste the positive potential of this action. Moreover, “race corrections” persist throughout medicine. The entire medical community must turn a critical eye to race-based stratification and downstream racial inequities (10,11).

Systems of power and oppression have long structured the pathologization of race and entrenched views of patients, trainees, and clinicians (2–4,10,11). Intentionally centering patient voices and considering trainee perspectives will be vital to moving medicine toward justice for patients, learners, colleagues, and the health care workforce of tomorrow.

Disclosures

J.A. Bervell reports serving on a speakers bureau for Google and receiving honoraria from TikTok. J.A. Diao reports being employed by Apple Inc. and PathAI Inc. R. Khazanchi reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for American Medical Association Council on Medical Education (unpaid) and receiving consultancy fees from the New York City Department of Hygiene and Mental Health. N. Nkinsi reports receiving honoraria from Adaptive Biotechnologies. J. Tsai reports having consultancy agreements with Quest. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Aletha Maybank, Dr. Vanessa Grubbs, Dr. Monica Hahn, Dr. Michelle Morse, Dr. Nwamaka Eneanya, Dr. David Goldfarb, Dr. Ruth Staus, Dr. Sophia Kostelanetz, Dr. Melanie Hoenig, Dr. David Jones, Dr. Ricky Grisson, Dr. Kristina Krohn, and Ms. Nichole Jefferson for their invaluable guidance, leadership, and mentorship. We also wish to acknowledge and thank the many other trainees, patients, activists, and scholars who have devoted their time and resources to advocate for kidney health equity.

This movement, including our contributions as trainees, was only possible due to centuries of tireless work by a wide breadth of advocates and activists. That breadth is reflected in the diversity of learners and practitioners in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social sciences, biological sciences, clinical laboratory science, informatics, business, law, and more who have worked together, alongside—and often led by—patients and their families, in the pursuit of health justice.

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the authors and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the ASN or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Author Contributions

A.S. Heffron, R. Khazanchi, and N. Nkinsi conceptualized the study, provided supervision, and were responsible for formal analysis, methodology, and project administration; A.S. Heffron, M. Kane, R. Khazanchi, and N. Nkinsi wrote the original draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and were responsible for data curation and visualization.

References

- 1.Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, Eneanya ND, Gadegbeku CA, Inker LA, Mendu ML, Miller WG, Moxey-Mims MM, Roberts GV, St Peter WL, Warfield C, Powe NR: A unifying approach for GFR estimation: Recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 2994–3015, 2021 10.1681/ASN.2021070988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DuBois WEB: The health and physique of the Negro American. 1906. Am J Public Health 93: 272–276, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts D: Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century, New York, The New Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington H: Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, New York, Doubleday, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubbs V: Precision in GFR reporting: Let’s stop playing the race card. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1201–1202, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.00690120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohottige D, Diamantidis CJ, Norris KC, Boulware LE: Racism and kidney health: Turning equity into a reality. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 951–962, 2021. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eneanya ND, Boulware LE, Tsai J, Bruce MA, Ford CL, Harris C, Morales LS, Ryan MJ, Reese PP, Thorpe RJ Jr, Morse M, Walker V, Arogundade FA, Lopes AA, Norris KC: Health inequities and the inappropriate use of race in nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 18: 84–94, 2022. 10.1038/s41581-021-00501-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santhosh L, Babik JM: Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open 3: e1920482, 2020. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tummalapalli SL, Ibrahim SA: Alternative payment models and opportunities to address disparities in kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 769–772, 2021 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS: Hidden in plain sight - Reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med 383: 874–882, 2020. 10.1056/NEJMms2004740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chadha N, Lim B, Kane M, Rowland B: Toward the Abolition of Biological Race in Medicine: Transforming Clinical Education, Research, and Practice, Berkeley, California, Institute for Healing & Justice in Medicine, 2020 [Google Scholar]