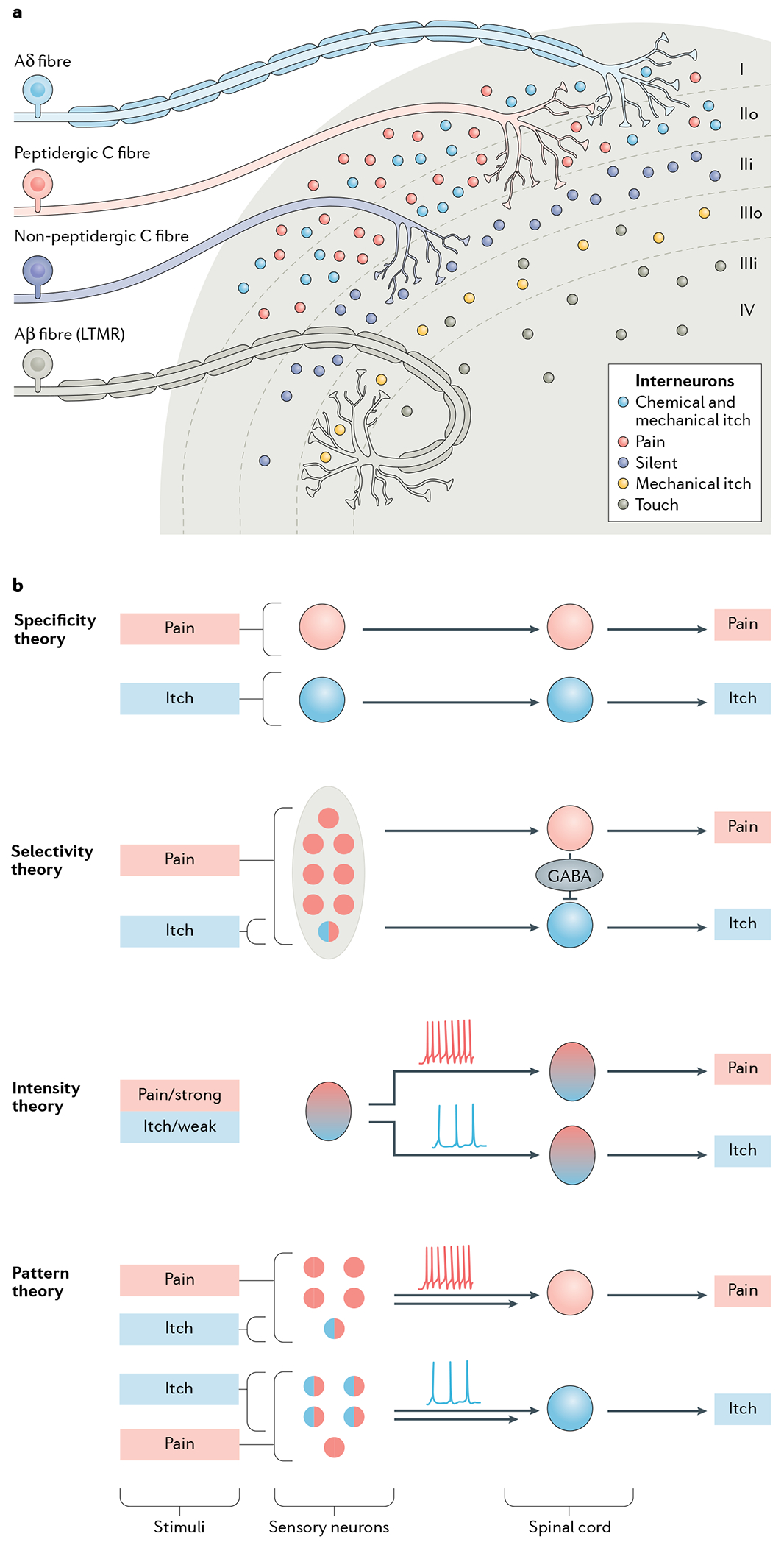

Fig. 1 |. Dorsal horn architecture and coding theories for itch.

a | The dorsal horn, illustrating its division into several distinct laminae (I–IV). Laminae I and II are innervated by unmyelinated C fibres and fast-conducting myelinated Aδ fibres, which together convey information relevant to pain, itch, pleasant touch and temperature sensing. Interneurons in laminae I and II additionally receive mechanical itch information from Aβ low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) via an indirect route (not shown)58,188. Lamina II can be subdivided into two layers: unmyelinated peptidergic C fibres terminate mainly in lamina I and the outer layer of lamina II and convey information that requires slow conduction velocities, such as that important for chemical itch and chemical pain33,247. The inner layer of lamina II is innervated mainly by unmyelinated non-peptidergic C fibres that convey pain, itch and other somatosensory information. Laminae III and IV are typically innervated by myelinated Aβ LTMR fibres that convey mechanical touch, mechanical itch and proprioceptive information32,33,58,188,193. Lamina III can be further divided into two layers. The outer layer contains TAC2 neurons, which mediate mechanical itch58. Dorsal horn projection neurons in lamina I and possibly laminae III and IV, integrate and relay itch information to the somatosensory cortex (not shown)61,75,248. b | The main current coding theories of itch. According to the specificity (or labelled line) theory, information about itch-inducing and painful stimuli is conveyed via distinct neural pathways from the skin to the spinal cord3. There are itch-specific neurons in the periphery, which are activated by itch stimuli exclusively.The selectivity (or population coding) theory proposes that pruriceptors (represented by a circle filled half in red and half in blue) are a small subset of nociceptive neurons. Pruriceptors respond to both itch-inducing and painful stimuli, whereas a much larger population of nociceptors (red) convey pain information exclusively3,19. This theory suggests that distinct labelled lines for pain and itch exist in the spinal cord and that pain transmission can activate spinal inhibitory neurons to inhibit or occlude itch by crosstalk between the two labelled lines34,35. According to the intensity theory, weak activation of nociceptors provokes itch, whereas strong activation of the same population of neurons evokes pain, via different modes of firing pattern (tonic for weak and burst for strong stimuli)3,10,12,13. Like the selectivity theory, the pattern theory3,34 postulates that within the larger population of sensory nociceptive neurons (red) there is a subset of pruriceptors (half red, half blue). However, it suggests that the distribution of these pruriceptors may be different in the epidermis and dermis (not shown). Therefore, depending on the nature and location of a given stimulus, a mixture of pruriceptors and nociceptors will be differentially activated, leading to different population firing patterns (tonic versus burst) and thereby encoding itch or pain specificity34,106. This theory does not explain how itch and pain information is encoded in the spinal cord. However, it can be assumed that itch and pain are conveyed separately in the spinal cord after the encoding by primary sensory neurons.