Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 outbreak beginning in late 2019 has resulted in negative emotions among the public. However, many healthcare workers risked their lives by voluntarily travelling to the worst-hit area, Hubei Province, to support antipandemic work. This study explored the mental health changes in these healthcare workers and tried to discover the influencing factors.

Design

A longitudinal online survey was begun on 8 February 2020, using the snowball sampling method, and this first phase ended on 22 February 2020 (T1). The follow-up survey was conducted from 8 February to 22 February 2021 (T2).

Setting

Healthcare workers from outside of the Hubei area who went to the province to provide medical assistance.

Participants

963 healthcare workers who completed both surveys.

Measures

Self-Rating Scale of Sleep (SRSS), Generalised Anxiety Scale (GAD-7) and 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

Results

There were no significant differences in the SRSS scores or in the GAD-7 scores between T1 and T2 (t=0.994, 0.288; p>0.05). However, the PHQ-9 score at T2 was significantly higher than the score at T1 (t=−10.812, p<0.001). Through multiple linear regression analysis, we found that the following traits could predict higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores at T2: male sex, single marital status, occupation of nurse, lower professional technical titles, healthcare workers having a history of psychosis, treating seriously ill patients, having relatively poor self-perceived health, caring for patients who died and having family members who had been infected with COVID-19.

Conclusions

The results indicate that the depression levels of these special healthcare workers increased in the long term, and the initial demographics and experiences related to the pandemic played an important role in predicting their long-term poor mental health. In the future, more appropriate psychological decompression training should be provided for these special healthcare workers.

Keywords: COVID-19, MENTAL HEALTH, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The participants included in this study sample had some homogeneity in their roles in the assistance work, which could guarantee that the conclusions can be extended to this special group.

The prospective study design (1 year of follow-up of the same sample) could help us to understand the participants’ long-term mental health changes compared with their initial data, which could also indicate the defeating work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study used the snowball sampling method and followed the voluntary principle to recruit subjects, which did not include the data of those who were not willing to expose their mental status considering the social influence.

The data were self-reported, and therefore, the participants’ mental health could only represent the probability of anxiety and depression, and could not represent the diagnosis.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak beginning in late 2019 has been spreading for over 2 years. Reports have suggested that the pandemic has resulted in negative emotions among the public.1 2 Even before the outbreak, healthcare workers tended to have long working hours, substantial work stress and emotional fatigue, putting them at higher risk of mental disorders than others who work in non-healthcare areas.3 4 After the sudden outbreak of COVID-19, the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the need for professional skills exacerbated the stress that healthcare workers were already experiencing. Thus, negative mental health outcomes were anticipated.5 6 However, many healthcare workers risked their lives by voluntarily travelling to the worst-hit area, Hubei Province, to support antipandemic work. It was reported that there were 25 633 voluntary medical workers from outside the Hubei area who offered medical assistance in the province beginning on 24 January 2020.7

To date, many studies have reported that the mental health of front-line healthcare workers has been impacted by the pandemic,8 9 with rates of anxiety and depression ranging from 12% to 23% and 15% to 27%, respectively.10 11 Other studies have investigated Chinese medical staff who had direct contact with COVID-19 patients and found that they were at high risk of psychopathology and experienced high rates of anxiety symptoms.11 12 However, these studies were all cross-sectional studies that were conducted during the initial phase of the outbreak. Maunder et al found that those who provided healthcare for SARS patients continued to experience substantial long-term psychological distress,13 and Matua et al also revealed that the impact on mental health caused by the Ebola pandemic persisted for a long time after the acute outbreak.14 Considering the pervasive and profound impact of large-scale outbreaks on the mental health of front-line healthcare workers,15 it is vital to conduct longitudinal surveys that could help us to understand the changes in their mental health and the profound impact of the ongoing pandemic.

After reviewing the latest studies that investigated the longitudinal changes in the mental health of healthcare workers, we found that most studies focused on the 1–4 months following the initial outbreak. They found that healthcare workers’ self-perceived job performance deteriorated over time, and they presented with common mental disorders.16–18 Their poor psychological well-being was generally stable over time but sometimes increased.19 20 To the best of our knowledge, the longest time interval studied was 8 months postoutbreak, where researchers found that during repeated outbreaks in Japan, the psychological distress in healthcare workers remained elevated and at the same level as that in the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak.21

The COVID-19 pandemic is showing signs of repeated outbreaks worldwide and of gradually becoming an ongoing battle for healthcare workers. It is important to understand the long-term impact on this population, especially for healthcare workers who voluntarily went to Hubei and were in contact with COVID-19 patients. Because the condition of the initial outbreak of COVID-19 was unknown, it might have become an obvious source of stress for these healthcare workers, and it was reported that a similar major disaster’s impact on mental health might last for a long period of time.22 Therefore, we designed this longitudinal study to identify the changes in the mental health of healthcare workers 1 year after the first outbreak and to explore what factors in the initial phase could influence their subsequent mental health. These findings, in turn, may help guide the creation of a psychological crisis intervention system to deal with similar situations in the future.

Methods

Design

This longitudinal online survey began on 8 February 2020, using the snowball sampling method, and the first phase ended on 22 February 2020 (T1). The follow-up survey was conducted from 8 February to 22 February 2021 (T2, nearly 1 year after the first outbreak of COVID-19 in China). The snowball sampling method was used to distribute the questionnaires online. Because of the convenience of the network and to acquire the latest information of these subjects, we chose the WeChat platform to distribute the first questionnaires to a group of healthcare workers who travelled to Hubei to offer medical aid. We also encouraged those who completed the questionnaires to forward the link to other healthcare workers who also travelled to Hubei to provide medical assistance. Informed consent was obtained on the first page of our questionnaires, and only when the participant clicked the button to consent could he or she access the survey. If an individual did not agree to participate, the survey would close automatically. To acquire longitudinal data, we included an invitation at the end of the survey to participate in the follow-up survey. Those who agreed to participate in the follow-up survey needed to leave their WeChat account information, which was used to deliver the second survey. The research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the medical centre.

Participants

Only healthcare workers from outside of the Hubei area who went to the province to provide medical assistance were selected as our subjects. A total of 1260 participants returned valid questionnaires in the first survey. Among them, only 1098 provided their WeChat account information for the next survey. After we delivered the second survey link through WeChat, 963 subjects returned valid questionnaires. The rate of loss to follow-up was 23.6% (297/1260). There were no systematic differences in demographic characteristics among the subjects who dropped out at T2.

Measurements

All the questionnaires used in our research were self-reported. The specific scales included (1) demographics and experiences related to the pandemic questionnaire, including gender/sex, age, marital status, highest education level, professional technical title, occupation (physician or nurse), history of psychosis, self-perceived health conditions (one indicated a very good physical condition; two indicated good; three indicated average; four indicated poor; five indicated very poor), number of working years, whether the COVID-19 patients they had treated died, whether they nursed/treated seriously ill COVID-19 patients, and whether their family members had been infected with COVID-19. This questionnaire was completed only at T1; (2) the Self-Rating Scale of Sleep (SRSS),23 which is composed of 10 items with scores of 1–5 points per item. The higher the score was, the worse the participant’s sleep problems. According to the report, the Chinese national norm was 22.14±5.48;24 (3) the Generalised Anxiety Scale (GAD-7) and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),25 26 which are the simplest scales used to evaluate levels of anxiety and depression. The GAD-7 consists of 7 items that receive 0–3 points each. The cut-off points for mild/moderate/severe anxiety were 5, 10 and 15, respectively. The PHQ-9 is composed of 9 items that receive 0–3 points each. The cut-off points for mild/moderate/moderately severe/severe depression were 5, 10, 15 and 20, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. The mean scores were then compared among time points using paired t-test statistics. The χ2 test was used to detect the differences in levels of anxiety and depression at different time points. Because the total GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were both close to a normal distribution, we used multiple linear regression with the stepwise method to screen the influencing factors for anxiety and depression. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science (V.11.0, IBM Corp).

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Results

Demographic data

There were 963 subjects who completed both surveys, among whom 521 were male and 442 were female. The age range was 23–40 years old, with an average age of 30.33±4.48 years. Regarding marital status, 488 subjects were married, and 475 were unmarried. Among them, there were 702 nurses and 261 physicians (all of them were clinical physicians). The number of working years of all subjects ranged from 2 to 20 years, with an average of 8.63±4.44 years. Eighty-one subjects reported a history of psychosis, including 69 with anxiety disorder and 12 with depression (all psychosis should be diagnosed by psychiatrists). Other demographic details and experiences related to the pandemic are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

The distribution of demographic characteristic and pandemic experiences (n=963)

| Variables and assignment | Means/N (%) |

| Gender | |

| Man (1) | 521 (54.1) |

| Woman (2) | 442 (45.9) |

| Ages (years) | 30.33±4.48 |

| Marriage | |

| Unmarried (1) | 475 (49.3) |

| Married (2) | 488 (50.7) |

| Widowed (3) | 0 |

| Highest education | |

| Secondary (1) | 70 (7.3) |

| Junior (2) | 351 (36.4) |

| Undergraduate (3) | 484 (50.3) |

| Graduate (4) | 58 (6.0) |

| Professional technical title | |

| Novice (1) | 518 (53.8) |

| Middle (2) | 361 (37.5) |

| Senior (3) | 84 (8.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Nurse (2) | 702 (72.9) |

| Physician (1) | 261 (27.1) |

| History of psychosis | |

| Yes (1) | 81 (8.4) |

| No (2) | 882 (91.6) |

| Self-perceived health conditions | |

| Very good (1) | 224 (23.3) |

| Good (2) | 598 (62.1) |

| Average (3) | 141 (14.6) |

| Poor (4) | 0 |

| Very poor (5) | 0 |

| Working years (years) | 8.63±4.44 |

| Whether the patients they treated had died | |

| Yes (1) | 306 (31.8) |

| No (2) | 657 (68.2) |

| Whether nursed/treated seriously ill patients with COVID-19 | |

| Yes (1) | 908 (94.3) |

| No (2) | 55 (5.7) |

| Whether their family members had been infected with COVID-19 | |

| Yes (1) | 31 (3.2) |

| No (2) | 932 (96.8) |

The SRSS, GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores at different time points

Overall, the mean SRSS score of all the subjects was significantly higher than the national norm of the SRSS (22.14±5.48) at both T1 and T2 (t=14.656, 14.064; p<0.001), indicating that the subjects’ sleep quality was poor. The mean GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores at T1 and T2 both indicated moderate anxiety and moderate depression among all the subjects.

When looking into the longitudinal changes in scores on these three scales, there were no significant differences in the SRSS scores or in the GAD-7 scores between T1 and T2 (t=0.994, 0.288; p>0.05), which means the sleep quality and the anxiety levels of the subjects did not show significant changes. However, the PHQ-9 score at T2 was significantly higher than the score at T1 (t=−10.812, p<0.001), which demonstrates that the depressive symptoms of the subjects had further deteriorated. The detailed data of the three scales are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

The disparity between the two time-points on the mean scores of SRSS, GAD-7 and PHQ-9 (n=963)

| T1 (mean±SD) |

T2 (mean±SD) |

T | P value | |

| SRSS | 25.20±6.48 | 24.91±6.12 | 0.994 | 0.320 |

| GAD-7 | 13.04±3.87 | 13.03±3.80 | 0.288 | 0.774 |

| PHQ-9 | 14.70±4.70 | 14.96±4.62 | −10.812 | <0.001 |

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Scale; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; SRSS, Self-Rating Scale of Sleep.

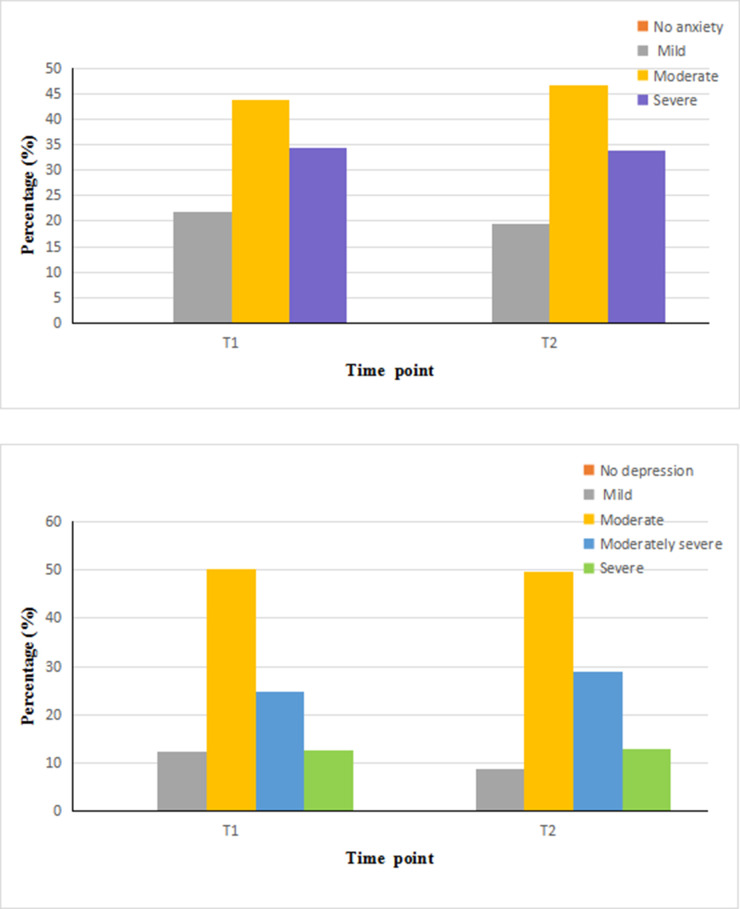

The rates of different degrees of anxiety and depression at different time points

We used the χ2 test to determine the differences in the rates of different degrees of anxiety and depression over time and found that there were no significant differences in the rates of mild, moderate and severe anxiety at the two time points (χ2=1.399; 1.528; 0.083, df=1, p>0.05). The rates of mild depression showed a significant decrease from T1 to T2 (χ2=6.687, df=1, p=0.012), and no significant change was found in the rates of other levels of depression (χ2=0.052; 3.823; 0.019, df=1, p>0.05). The detailed comparison results and the distribution of severity of anxiety and depression are listed in table 3 and figure 1.

Table 3.

The rates of different degrees of anxiety and depression symptoms among different time points (n=963)

| T1 % (n) |

T2 % (n) |

χ2 | P value | |

| GAD-7 | ||||

| No anxiety | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Mild anxiety | 21.7 (209) | 19.5 (188) | 1.399 | 0.260 |

| Moderate anxiety | 43.8 (422) | 46.6 (449) | 1.528 | 0.234 |

| Severe anxiety | 34.5 (332) | 33.9 (326) | 0.083 | 0.810 |

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| No depression | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Mild depression | 12.5 (120) | 8.8 (85) | 6.687 | 0.012 |

| Moderate depression | 50.1 (482) | 49.5 (477) | 0.052 | 0.855 |

| Moderately severe depression | 24.8 (239) | 28.9 (277) | 3.823 | 0.057 |

| Severe depression | 12.7 (122) | 12.9 (124) | 0.019 | 0.946 |

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Scale; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

The distribution of severity of anxiety and depression over time. The first figure stands for the anxiety level, and the second one stands for the depression level.

Multiple linear regression analysis of long-term influencing factors of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 total scores

To build the prediction model, we included all the demographic variables and experiences related to the pandemic as independent variables. The assignments of all variables are shown in table 1. Because sleep quality is usually associated with anxiety and depression, we also considered the SRSS score at T1 as one of the independent variables.

Through multiple linear regression, we found that the following factors could predict higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores at T2: male sex, unmarried marital status, the occupation of nurse, a lower professional technical title, having a history of psychosis, having nursed/treated seriously ill COVID-19 patients, having relatively poor self-perceived health conditions, having the patients they treated die and having family members infected with COVID-19. Subjects with fewer working years showed higher GAD-7 scores, and younger respondents showed higher PHQ-9 scores. The F values (11, 951) in the regression equation were 120.160 and 271.902 (p<0.001) for the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, respectively. The adjusted R2 values were 0.577 and 0.756, which means that the screened influencing factors could effectively explain 57.7% and 75.6% of the variance in the two models. The results of the influencing factors of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores are listed in table 4 and table 5.

Table 4.

The multiple linear regression analysis of influencing factors of GAD-7

| Variable | Regression coefficients | SE of regression coefficient | Standardised regression coefficient | T | P value | 95% CI |

| Constant | 26.394 | 1.432 | 18.432 | <0.001 | (23.584 to 29.204) | |

| Gender | −3.402 | 0.195 | −0.446 | −17.406 | <0.001 | (−3.786 to −3.019) |

| History of psychosis | −3.340 | 0.359 | −0.244 | −9.308 | <0.001 | (−4.044 to −2.636) |

| Whether nursed/treated seriously ill patients with COVID-19 | −6.174 | 0.392 | −0.377 | −15.732 | <0.001 | (−6.945 to −5.404) |

| Self-perceived health conditions | 2.234 | 0.158 | 0.359 | 14.169 | <0.001 | (1.925 to 2.544) |

| Whether the patients they treated had died | −2.195 | 0.240 | −0.269 | −9.142 | <0.001 | (−2.666 to −1.724) |

| Whether their family members had been infected with COVID-19 | −2.700 | 0.537 | −0.125 | −5.030 | <0.001 | (−3.753 to −1.646) |

| Marriage | −0.732 | 0.222 | −0.096 | −3.292 | 0.001 | (−1.168 to −0.296) |

| Occupation | 1.731 | 0.301 | 0.202 | 5.748 | <0.001 | (1.140 to 2.322) |

| Professional technical title | −1.551 | 0.253 | −0.265 | −6.126 | <0.001 | (−2.047 to −1.054) |

| Working years | −0.091 | 0.029 | −0.106 | −3.165 | 0.002 | (−0.147 to −0.035) |

F (11, 951) = 120.160 (p<0.001), R=0.763, R2=0.577.

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Scale.

Table 5.

The multiple linear regression analysis of influencing factors of PHQ-9

| Variable | Regression coefficients | SE of regression coefficient | Standardised regression coefficient | T | P value | 95% CI |

| Constant | 37.648 | 1.618 | 23.267 | <0.001 | (34.472 to 40.823) | |

| Gender | −1.482 | 0.196 | −0.160 | −7.559 | <0.001 | (−1.866 to - 1.097) |

| History of psychosis | −10.461 | 0.332 | −0.629 | −31.543 | <0.001 | (−11.112 to -9.811) |

| Whether nursed/treated seriously ill patients with COVID-19 | −5.280 | 0.350 | −0.266 | −15.069 | <0.001 | (−5.967 to − 4.592) |

| Self-perceived health conditions | 1.930 | 0.150 | 0.255 | 12.879 | <0.001 | (1.636 to 2.224) |

| Whether the patients they treated had died | −2.232 | 0.220 | −0.225 | −10.164 | <0.001 | (−2.662 to − 1.801) |

| Whether their family members had been infected with COVID-19 | −4.217 | 0.510 | −0.161 | −8.272 | <0.001 | (−5.218 to − 3.217) |

| Marriage | −1.480 | 0.216 | −0.160 | −6.858 | <0.001 | (−1.903 to − 1.056) |

| Occupation | 1.283 | 0.278 | 0.124 | 4.619 | <0.001 | (0.738 to 1.829) |

| Professional technical title | −2.221 | 0.292 | −0.313 | −7.608 | <0.001 | (−2.794 to − 1.648) |

| Age | −0.350 | 0.043 | −0.340 | −8.129 | <0.001 | (−0.434 to - 0.265) |

F (11, 951) = 271.902 (p<0.001), R=0.871, R2=0.756.

PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Discussion

Through this longitudinal survey, we discovered that 1 year after the first outbreak of COVID-19, sleep quality and anxiety levels remained stable among the 963 healthcare workers who voluntarily went to Hubei to provide medical support, while their levels of depression showed an obvious increase compared with their condition in their first month of assistance. Initial demographic characteristics, including gender/sex, marital status, occupation, professional technical titles, psychosis history and their experiences with pandemic-defeating work might predict the degree of anxiety and depression in the long term.

Notably, compared with the score at T1, the mean SRSS score showed no significant change 1 year after our subjects’ assistance missions during the outbreak of COVID-19, both of which were significantly worse than that of the national norm, which demonstrates that the sleep quality of our subjects remains poor although they have been back to their own workplace for a long time. One study investigating the impact of assistance work on healthcare workers discovered that poor sleep quality was still common 1 month after they arrived in Hubei during the COVID-19 outbreak,17 which was similar to our finding. However, no literature continues to study how their sleep quality changes one year later, and our results could make up the margin. The reason why their sleep quality was still poor over a long period of time might depend on the nature of their job, such as over-loaded work,27 and the night-shift rules,28 which can make their sleep poor, while the subsequent repeated outbreaks of COVID-19 in different scales in China keep them at high alert, which might also be related to their poor sleep quality.28

With regard to the mean scores on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, we found that the respondents’ anxiety scores did not show significant changes from T2 to T1, while their depression scores increased significantly, and all of them had a moderate level of depression, which indicated that the mental health of these healthcare workers was still poor 1 year later, and that the pandemic’s impact on this special group might persist for a long time. To our surprise, no respondents reported themselves as having no anxiety and/or depressive symptoms in either survey. Many studies have revealed that the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in medical staff working in the areas most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic was high;12 29–31 the prevalence of anxiety ranged from% 23 to 34%, and the prevalence of depression ranged from 15% to 27% according to various meta-analyses.32–34 The reason for the obviously different prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in our results might be due to the different tools used and the different stages in which the surveys were conducted.35 The subjects in our study belong to a special group that faced an unknown new virus, and many of them may not have had previous experience with a serious pandemic; the complex COVID-19 facing environments in the new workplace and the strict closed-loop management during their time in Hubei might have caused more emotional stress.36 Hence, it is not surprising that all of the healthcare workers showed some extent of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the initial phase.

However, after their return, we uniquely found that they continued to have high levels of anxiety and depression. López et al found that from the first measurement to the 4-month follow-up in their study, more healthcare workers presented anxiety and depression during the pandemic.16 Because there was no literature investigating the long-term impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers, we could only refer to the experiences of past pandemics when setting up our research. We know that the symptoms of anxiety and depression were still common among healthcare workers within one to three years after the SARS outbreak.37 38 We could see the profound and persistent impact caused by that pandemic. However, there are differences between COVID-19 and SARS. COVID-19 has been repeatedly ongoing, which might keep healthcare workers in a constant state of being alert or preparing for outbreaks, guarding against unexpected contacts, and facing the risk of infection or transmission to their family members,39 40 which could be torturous and exhausting. Therefore, the mental health of our subjects remained poor 1 year later. When looking at the depression score, it deteriorated further at T2, and more subjects reported moderately severe depression at T2, which indicates that the degree of depression worsened over time. One probable reason might be the delayed reaction caused by serious disaster-related events.41 42 Another reason might be the recession of anxiety. Healthcare workers with an overload of emotional pressure may become exhausted; as time passes, they do not have enough energy to worry and they gradually develop more severe depression.43

According to our results, the long-term influencing factors for anxiety and depressive symptoms were similar regarding aspects of experiences related to COVID-19, including having nursed/treated seriously ill COVID-19 patients, having the patients they treated die and having family members infected with COVID-19, which could predict the prevalence of anxiety and depression in our subjects. Other reports also revealed that poorer mental health was associated with managing COVID-19 patients and family exposure to COVID-19.19 44

Regarding demographic factors, we found that healthcare workers with a history of psychosis were more prone to show anxiety and depressive symptoms, which was similar to the findings of other studies.13 16 17 We also discovered that those who thought of themselves as having relatively poor health experienced more anxiety and depression, which was similar to the findings of Manara et al.45 Another factor screened was gender/sex, and we found that male healthcare workers tended to report more anxiety and depressive symptoms, which was contrary to previous studies.46 47 The reason might be that the male healthcare workers are generally older, and their physical strength and energy recovery level would therefore not be as fast as that of young women. Thus, they are more prone to fatigue. In addition, women are considered to be more willing to express their feelings through language than men,48 which might seem to be another kind of emotional release leading to less negative emotions being stored.49

Individuals with other factors, including being unmarried, being a nurse and having a lower professional technical title, were prone to present greater anxiety and depression, which was in contrast to Cai et al’s report.50 We all know that communication with family and companions are important sources of social support,51 but unmarried individuals do not have the support of spouses. Due to the large number of infected patients in Hubei Province, more nurses were required to care for them and to conduct clinical treatment activities, such as blood sampling, infusions and medication distribution. The great workload undoubtedly added more pressure for nurses than physicians, and the nurses were relatively young with lower professional technical titles and less experience, making them vulnerable to distress.44 Finally, we found that healthcare workers with fewer years of work were more likely to become anxious, and younger individuals were more likely to become depressed, which was similar to previous findings.13 44 46

Conclusions

The COVID-19 outbreak beginning in late 2019 has been spreading for almost 2 years. After the sudden outbreak of COVID-19, the shortage of PPE placed additional stress on professional healthcare workers. However, there has been little information on the changes in the mental health of healthcare workers who went to Hubei to offer assistance. This is the first study investigating the longitudinal mental health of front-line healthcare workers who went to Hubei to assist other health professionals during the initial COVID-19 outbreak and 1 year later. We found that sleep quality and anxiety levels remained stable among healthcare workers, while their depression levels showed obvious increases. The initial demographic characteristics and experiences related to the pandemic played an important role in predicting the long-term mental health of these special healthcare workers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ND was responsible for the overall content as the guarantor, and she was also in charge of supervising the process and providing expert opinions. PZ and ND organised the study design and analysed the data. Collaborators YX and Y-GL ensured that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved. C-YL and TG participated in conducting the survey and typing the data. PZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and ND critically revised it. PZ, ND, YX, Y-GL, C-YL and TG approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by The Fourth People’s Hospital of Chengdu. Because our study used the method of questionnaire investigation, not involved the information of patients and related intervention, we applied for the simple ethics approval procedure. The version of this file did not include the reference number. It only contained the signature of the commissioner and the official stamp of the institutional board. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, et al. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:281–2. 10.1111/pcn.12988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao H, Chen J-H, Xu Y-F. Rethinking online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;50:102015. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng W-J, Cheng Y. Minor mental disorders in Taiwanese healthcare workers and the associations with psychosocial work conditions. J Formos Med Assoc 2017;116:300–5. 10.1016/j.jfma.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283:516–29. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold JA. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ;116:m1815. 10.1136/bmj.m1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walton M, Murray E, Christian MD. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020;9:241–7. 10.1177/2048872620922795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2020. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, et al. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2997. 10.3390/ijerph17092997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang Y-T, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:228–9. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamb D, Gnanapragasam S, Greenberg N, et al. Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occup Environ Med 2021;78:801–8. 10.1136/oemed-2020-107276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976–e76. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C-Y, Yang Y-Z, Zhang X-M, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:E98. 10.1017/S0950268820001107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:1924–32. 10.3201/eid1212.060584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matua GA, Wal DMVder, Van der Wal DM. Living under the constant threat of ebola: a phenomenological study of survivors and family caregivers during an ebola outbreak. J Nurs Res 2015;23:217–24. 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busch IM, Moretti F, Mazzi M, et al. What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers. Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:178–90. 10.1159/000513733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López Steinmetz LC, Herrera CR, Fong SB, et al. A longitudinal study on the changes in mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry 2022;85:56–71. 10.1080/00332747.2021.1940469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, Ding H, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence of poor psychiatric status and sleep quality among frontline healthcare workers during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: a longitudinal study. Transl Psychiatry 2021;11:1–6. 10.1038/s41398-020-01190-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Que J, Shi L, Deng J, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33:e100259. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan J-A, Shannon C, Browne D, et al. COVID-19 staff wellbeing survey: longitudinal survey of psychological well-being among health and social care staff in Northern Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 2021;7:E159. 10.1192/bjo.2021.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki N, Kuroda R, Tsuno K, et al. The deterioration of mental health among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: a population-based cohort study of workers in Japan. Scand J Work Environ Health 2020;46:639–44. 10.5271/sjweh.3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki N, Asaoka H, Kuroda R, et al. Sustained poor mental health among healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of the four-wave panel survey over 8 months in Japan. J Occup Health 2021;63:e12227. 10.1002/1348-9585.12227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen PJ, Pusica Y, Sohaei D, et al. An overview of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diagnosis 2021;8:403–12. 10.1515/dx-2021-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J-Y L. Seff-Rating Scale of Sleep(SRSS). Chin J Health Psychol 2012;20:1851. [Google Scholar]

- 24.J-Y L, Duan S-F, Zhang J-J. Analysis rating of sleep state of 13273 normal persons. J Health Psychol 2000;8:351–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.X-Y H, C-B L, Qian J, et al. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2010;22:200–3. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2010.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, et al. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:71–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdalla M, Chiuzan C, Shang Y, et al. Factors associated with insomnia symptoms in a longitudinal study among New York City healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:8970. 10.3390/ijerph18178970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganesan S, Magee M, Stone JE, et al. The impact of shift work on sleep, alertness and performance in healthcare workers. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-019-40914-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Y, Wu K, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health in frontline medical workers during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease epidemic in China: a comparison with the general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6550. 10.3390/ijerph17186550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS One 2020;15:e0238217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, et al. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19 - a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci 2020;18:Doc05. 10.3205/000281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, et al. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113382. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, et al. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:9096. 10.3390/ijerph17239096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901–7. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung GM, Ho L-M, Chan SKK, et al. Longitudinal assessment of community psychobehavioral responses during and after the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1713–20. 10.1086/429923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Liu J, Chen M, et al. Sleep problems of healthcare workers in tertiary hospital and influencing factors identified through a multilevel analysis: a cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032239. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:241–7. 10.1177/070674370705200406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:302–11. 10.1177/070674370905400504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Huang D, Huang H, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Med 2022;52:1–9. 10.1017/S0033291720002561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji D, Ji Y-J, Duan X-Z, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget 2017;8:12784–91. 10.18632/oncotarget.14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ran M-S, Zhang Z, Fan M, et al. Risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asian J Psychiatr 2015;13:66–71. 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:611–27. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du N, Zhou Y-ling, Zhang X, et al. Do some anxiety disorders belong to the prodrome of bipolar disorder? a clinical study combining retrospective and prospective methods to analyse the relationship between anxiety disorder and bipolar disorder from the perspective of biorhythms. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:1–16. 10.1186/s12888-017-1509-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, et al. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;369:m1642. 10.1136/bmj.m1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manara DF, Villa G, Korelic L, et al. One-week longitudinal daily description of moral distress, coping, and general health in healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: a quantitative diary study. Acta Biomed 2021;92:e2021461. 10.23750/abm.v92iS6.12313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu J, Sun L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:386. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113441. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liddon L, Kingerlee R, Barry JA. Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers to help-seeking. Br J Clin Psychol 2018;57:42–58. 10.1111/bjc.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denton K, Zarbatany L. Age differences in support processes in conversations between friends. Child Dev 1996;67:1360–73. 10.2307/1131705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in hunan between january and march 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit;2020:e924171. 10.12659/MSM.924171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Mann F, Lloyd-Evans B, et al. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:1–16. 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.